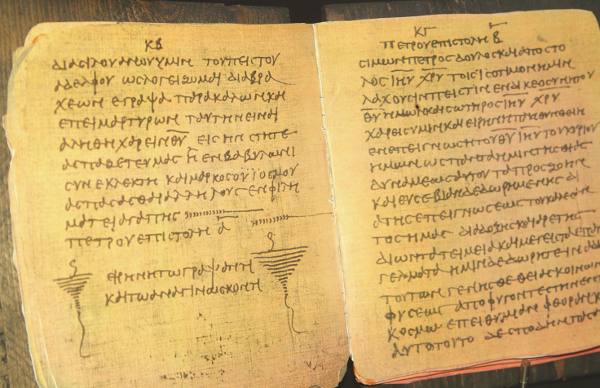

Annotations for 2 Peter

1:1 Simon. In Greek, the name here is “Simeon,” a common Jewish name (cf. Ge 29:33), rather than the usual Greek equivalent “Simon” commonly used in the NT. our God and Savior Jesus Christ. Jewish people sometimes used savior as a divine title, an approach inevitable when conjoined with God (cf., e.g., Ps 85:4; Isa 45:15, 21; Mic 7:7).

1:2 Grace and peace. See note on Ro 1:7.

1:4 you may participate in the divine nature. Many Greek thinkers believed that humans could become (or the soul was already) divine; some Diaspora Jews used this language, although they believed in just one God. Most Jews denied that humans could become divine (cf. Ge 3:5). When Diaspora Jews spoke of participating “in the divine nature,” they usually referred to becoming immortal. Peter probably evokes especially the early Christian view of God’s Spirit transforming believers’ moral character in Christ (see note on 1Pe 1:23.) escaped the corruption in the world caused by evil desires. Many Greek thinkers in this period wanted to escape the material world of decay around them, believing that their soul was divine and immortal and belonged in the pure and perfect heavens above; some Greek thinkers and cults provided this idea as a hope for the masses. Peter associates the corruption instead with evil desires (cf. 2:14; 3:3).

1:5–7 Both Jews and Gentiles used the literary form of adding one virtue, vice or some other next step to a former one (cf., e.g., Wisdom of Solomon 6:17–20).

1:5 goodness. The Greek term (aretê) was the catchall Greek virtue, representing nobility of character.

1:7 love. The climactic virtue, in accordance with Jesus’ teaching (see note on 1Co 13:13).

1:10 confirm your calling and election. Jewish tradition applied calling and election to God’s people Israel; here Peter applies it to Christian believers.

1:12 I will always remind you. Moral teachers would often exhort people, noting that they were simply “reminding” them of truths.

1:13 the tent of this body. Many ancient thinkers described the body as a tent (cf. note on 2Co 5:1).

1:14 I will soon put it aside. Jewish people and some others paid special attention to the last words of someone expected to die soon. The Greek term here translated “put it aside,” along with related terms, had a range of meaning (cf. James 1:21 [“get rid of”]; 1Pe 3:21 [“removal of”]), sometimes including putting off clothing (cf. Ro 13:12; Eph 4:22).

1:16 stories. Lit. “myths”; usually used pejoratively and contrasted with true accounts from eyewitnesses. coming . . . in power. Here refers to Jesus’ transfiguration (Mk 9:1–3), of which Peter was an eyewitness (Mk 9:2, 5).

1:17 from the Majestic Glory. “The Glory” was sometimes a Jewish circumlocution for God; Peter may use it here to reinforce the transfiguration’s allusion to Sinai (see notes on v. 18; Mk 9:2). my Son . . . with him I am well pleased. The quotation here precisely matches Mt 3:17 (for the heavenly voice, see note there); in terms of Mark’s Gospel, it blends the voice at the baptism (Mk 1:11) with the voice at the transfiguration (Mk 9:7).

1:18 voice that came from heaven . . . on the sacred mountain. God spoke from heaven at the giving of the law (Dt 4:36) and revealed himself to Moses on another sacred mountain, Mount Sinai. He also promised a new and greater revelation on Mount Zion (Isa 2:2–4), what Scripture often called God’s holy mountain (the same words in Greek, in, e.g., Ps 2:6; 3:4; 15:1; Joel 3:17). Although the transfiguration was not on Mount Zion per se, the place of his transfiguration became a sacred mountain the same way that Sinai did—the Lord revealed himself there. It thus foreshadowed the future revelation of God on Mount Zion. Jewish tradition recognized that God sometimes spoke from heaven, although later rabbis subordinated the authority of such revelation to Scripture itself.

1:19 the prophetic message . . . completely reliable. Jewish people embraced the Scriptures as God’s word; the new revelation in Christ confirmed earlier prophecies and itself was worthy of being regarded as Scripture (cf. also 3:16). light shining in a dark place, until the day dawns. Scripture remains the essential light in darkness (Ps 119:105) until the day of the Lord fully dawns (cf. Isa 60:1). the morning star rises in your hearts. The day of the Lord would be like a sunrise (Mal 4:2); some ancient Jewish traditions apply the “star” of Nu 24:17 to the Messiah. The morning star (Venus) heralds the advent of dawn; a new age was about to dawn (cf. v. 11; 3:13).

1:20–21 no prophecy . . . by the prophet’s own interpretation of things . . . but prophets . . . were carried along by the Holy Spirit. Ancient thinkers often viewed prophetic inspiration as a divine possession that temporarily displaced the prophet’s own mind. The distinctive styles of different Biblical prophets shows that this view oversimplifies the matter; inspiration still used human faculties and vocabulary (cf. 1Pe 1:10–12; 1Co 7:40; 14:1–2, 14–19), although there may have been different levels and kinds of ecstasy (cf. 1Sa 10:10–11; 19:20–24; 1Co 14:2; 2Co 5:13; 12:4). Regardless of particulars, however, ancient thinkers (and especially Jewish thinkers) generally expected inspiration to protect the inspired agents from misrepresenting the divine message (contrast 2:1).

2:1 false prophets. In earlier Scripture, false prophets spoke from their own imaginations rather than from divine inspiration (Jer 23:16, 18–22, 25–32; Eze 13:3–9); they often comforted people in their sin rather than speaking God’s true warning of divine judgment (Jer 6:14; 23:17; 28:9; Eze 13:10, 16). bringing swift destruction on themselves. Prophets who led people away from the Lord merited death (Dt 13:5).

2:2 bring the way of truth into disrepute. Just as many people despised all philosophers due to greedy sages, minority faiths suffered when self-proclaimed representatives of their groups generated scandals. (This happened in Rome, e.g., both to Jews and devotees of Isis; cf. note on Ro 2:17–24.)

2:3 exploit you with fabricated stories. The problem was widespread in the culture; nobler sages often lamented that some other sages or alleged wonderworkers exploited people to gain money. Earlier, see, e.g., Jer 6:13; 8:10; Mic 3:11. Here teachers value their financial gain more than they value the one who once bought them (v. 1).

2:4 did not spare angels when they sinned, but sent them to hell. Most ancient Jewish traditions understood the “sons of God” in Ge 6:1–4 as angels who lusted after women and so fell. hell. The Greek term here is from the name Tartarus, a place in Greek mythology where the most wicked (including earlier immortals called the Titans) were tortured in the worst imaginable ways. Some other Jewish sources borrow it to name the place where the fallen angels were imprisoned. Some Jewish people also spoke of the wicked as in hell (Gehinnom) until the final judgment, as well as afterward. A widely circulated Jewish source (Sirach 16:7–8) spoke of God not “sparing” the offspring of the angels in Noah’s day or (later) Sodom (as here in vv. 4–6).

2:5 brought the flood on its ungodly people. Jewish people usually associated the fallen angels (their understanding of Ge 6:2–4) with judgment on Noah’s generation (Ge 6:7–8). Tradition often elaborated stories about Noah, often depicting Noah as a preacher of repentance. Jewish teachers considered the flood generation as especially wicked and damned, and used the flood story to warn their own generation to repent in view of coming judgment.

2:6 condemned . . . Sodom and Gomorrah by burning them. Jewish teachers often coupled Sodom with the flood generation as examples of just objects of judgment. Biblical prophets earlier warned against acting like Sodom, which exemplified sin and judgment (Dt 32:32; Isa 1:9–10; 3:9; 13:19; Jer 23:14; 49:18; La 4:6; Eze 16:46, 49; Am 4:11; Zep 2:9).

2:7–8 Lot, a righteous man . . . tormented in his righteous soul. Although Jewish thinkers differed over whether Lot was righteous, Scripture portrays him as personally righteous (Ge 18:25; 19:1–16). Lot was less faithful than Abraham (Ge 13:10–11; 19:29, 32–35), but by Sodom’s standards he was intolerably righteous (Ge 19:9, 15).

2:9 hold the unrighteous for punishment on the day of judgment. Jewish traditions often depict the wicked being tortured in Gehenna, whether indefinitely, until the day of judgment, or until their annihilation. In Wisdom of Solomon 10:6, Wisdom “rescued the righteous one,” Lot, when the ungodly perished in the fire of Sodom.

2:10 not afraid to heap abuse on celestial beings. Some Jewish people (exemplified in the Dead Sea Scrolls and some Jewish teachers) cursed Satan or demons. (By contrast, the Sodomites [v. 6; Ge 19:1–29] tried to molest angels but were unaware that they were angels.) They may have insulted both earthly authorities (behavior that readily invited persecution when known) and the angelic authorities behind them (see note on Eph 1:21).

2:12 animals . . . born only to be caught and destroyed. Ancient writers regarded some animals as existing only to be killed for food; here the animals are objects of the hunt. creatures of instinct. Philosophers characterized animals as creatures ruled by instinct as opposed to humans, who were ruled by reason; they considered unreasoning humans to be animals.

2:13 to carouse in broad daylight. Because most people who partied did so at night, one who caroused “in broad daylight” was regarded as particularly uncontrolled.

2:14 eyes full of adultery. Some Jewish teachers warned about adultery of the eyes (see note on Mt 5:28) or of one looking for adulterous partners (Peter here says lit. “eyes full of an adulteress”). experts. The Greek term refers to persons trained or disciplined in something; whereas ancient teachers often spoke of moral training to resist greed, these false teachers have instead developed expertise in greed. accursed brood! Could either be a Semitic figure of speech for accursed ones or refer to disinherited children who received curse instead of blessing from parents.

2:15 the straight way . . . the way of Balaam. The contrast between the two ways may reflect the common ancient image of two paths, one leading the righteous or wise to life, the other leading the foolish to destruction. the way of Balaam . . . who loved the wages of wickedness. Especially when inspired (cf. 1:20–21; Nu 24:4, 13, 16), Balaam knew that God blessed those who blessed Israel and cursed those who cursed them (Nu 23:20; 24:9). Nevertheless, to gain wealth (Nu 22:7, 17; 24:11; Dt 23:4), Balaam showed Israel’s enemies how to remove God’s protection from Israel—by enticing Israelites into sexual sin (Nu 31:16; cf. Nu 23:21). For his sin Balaam himself reaped death (Nu 31:8; Jos 13:22). Jewish tradition depicted him as the greatest prophet of the Gentiles but also very wicked; he harmed Israel worse than more direct attackers by separating Israel from God’s blessing. Thus these teachers also lead others into sexual sin (v. 14), seeking profit (v. 3).

2:16 rebuked . . . by a donkey. Despite a miraculous warning through an animal that proved wiser than Balaam was (cf. the implications in v. 12), Balaam proceeded with his moral insanity (Nu 22:20–35). Jewish thinkers used Balaam as an example for fools who would be damned, and some elaborated the Biblical story further.

2:17 springs without water. No springs at all were better than springs without water; the latter raised thirsty travelers’ hopes in vain. Blackest darkness. Some Jewish sources depicted hell as both darkness and fire.

2:19 promise them freedom. Greek and Diaspora Jewish thinkers often spoke of freedom from passion (see note on Jn 8:34). slaves. Those defeated in war were often enslaved; ancient thinkers also regarded as slaves those subject to their passion.

2:21 not to have known the way of righteousness. Jewish people often spoke of “the way of righteousness” (cf. v. 15).

2:22 A dog returns to its vomit. Pr 26:11 depicts a fool returning to folly as a dog returning to its vomit. A sow . . . returns to her wallowing. This proverb comes from a version of the well-known story of Ahiqar. Other Jewish people associated dogs and pigs, since both were deemed unclean (cf., e.g., Mt 7:6; Isa 66:3).

3:1–16 Those heavily influenced by the Greek thought of the surrounding culture would not understand a future day of judgment. Like many Jewish teachers, Peter recognizes that minimizing future judgment encouraged immoral behavior or even moral relativism (see note on 2:1).

3:1 reminders. See note on 1:12.

3:2 the command given by our Lord. May include sayings about readiness such as Mt 24:42–44 (parallel to Lk 12:38–40), which mentions Jesus’ return like a thief (cf. 2Pe 3:10).

3:3 the last days. The promised future time of restoration (Isa 2:2; Eze 38:16; Hos 3:5; Mic 4:1), but applicable to the present era between the Messiah’s first and second comings (cf. Ac 2:17). scoffers . . . following their own evil desires. Many believed that those who doubted future judgment would behave immorally.

3:4–9 Delays often caused doubts (Eze 12:27–28; Hab 2:3); the authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls also addressed delays in the expected day of judgment. Misunderstanding about the delay began even before Jesus departed (e.g., Mk 10:37; Ac 1:6).

3:4–5 For the promise of Jesus’ coming, see Mt 24:27, 37, 39.

3:4 our ancestors. Although some plausibly argue that this phrase refers to the first generation of Christians looking for Jesus’ return, this seems an odd way to refer to those not genetically related. Jewish people might use this language for their ancestors, especially the patriarchs (literally, as here, “the fathers”), as even in early Christian works such as 1 Clement 62.2; Epistle of Barnabas 5.7; 14.1. Gentiles could also think of their ancestors. The point in these cases would be simply that nothing significant changed over the generations. Some Gentiles rejected primeval stories about ancient heroes as myths. everything goes on as it has since the beginning. Many thinkers (such as Aristotle) believed that the universe had neither beginning nor ending. Some (such as Epicureans) contended that the basic substance of matter could not be destroyed; some others (such as Stoics) contended that the universe would periodically be resolved into the primeval fire (see note on v. 7) and that eternity was a cycle of ages.

3:5 by God’s word the heavens came into being and the earth was formed. Even Diaspora Jewish thinkers discussed whether God created the universe from nothing (cf. Jn 1:3) or formed it from preexisting matter. On God creating by his word, see note on Jn 1:3. out of water and by water. The Greek philosopher Thales saw water as the primal element (though Peter’s wording is much more ambiguous).

3:7 the present heavens and earth are reserved for fire. God had promised after Noah’s flood (Ge 6–9) never to destroy the earth by water again (Ge 9:15; Isa 54:9), but the prophets did speak of a future fiery judgment and renewal of the present world (cf. Isa 65:17; 66:15, 22). Jewish tradition declared that the present world would be destroyed not by water but by fire, and sometimes used the flood as a symbol for the future judgment by fire. (Plato also expected the world to end once by flood and once by fire.) Stoics expected the universe to collapse into primeval fire, be re-created, and the cycle to continue indefinitely. Jewish thought more often envisioned a future day of judgment followed by an eternal new (usually renewed) creation (cf. vv. 10, 12–13).

3:8 a day is like a thousand years. Peter appeals to Ps 90:4 to make his point, as did many other Jewish writers of his day (who sometimes took “the day as a thousand years” literally and applied it to the days of creation). Some apocalyptic writers lamented that God did not reckon time as mortals do and consequently urged perseverance.

3:9 promise. Of Jesus’ coming (v. 4). he is patient. God’s patience may partly allude to the Noah analogy (vv. 5–7; cf. 1Pe 3:20; Ge 6:3). God sometimes delayed judgment to allow opportunity for the wicked to repent (cf. 2Ki 14:26–27). Some ancient Jewish sources emphasized God’s patience regarding the day of judgment; once that day arrived, repentance was no longer possible.

3:10 the day of the Lord. Biblical prophets warned of the ultimate day of God’s judgment as the day of the Lord, his day in court when he settles injustices (e.g., Isa 2:12; Joel 1:15; Am 5:18–20). (In the Prophets, nearer judgments often foreshadowed this ultimate one.) come like a thief. Echoes Jesus’ words (Mt 24:43; parallel in Lk 12:39). elements will be destroyed by fire. Ancient thinkers discussed the elements, usually envisioned as four: earth, water, air and fire. Some Greek thinkers (Stoics) spoke of the entire cosmos being renovated by fire; Jewish apocalyptic thinkers also envisioned the destruction or (more often) purifying renewal of heaven and earth.

3:11 live holy and godly lives. Some apocalyptic thinkers shared Peter’s interest in moral application; others instead focused on speculating about the future. The sort of future hope often embodied in apocalyptic sources appealed particularly to those who saw themselves as suffering during the present age; hope provided strength to persevere.

3:12 speed its coming. Jewish teachers disputed whether God had fixed the time of the end of the age or allowed it to be speeded by Israel’s repentance and obedience. Here, because God has delayed the end to allow more people to repent (vv. 9, 15), sharing Christ presumably speeds its coming (cf. Mt 24:14). elements. See note on v. 10.

3:13 a new heaven and a new earth, where righteousness dwells. Many ancient Jewish writers celebrated the Biblical promise of the new heavens and earth (Isa 65:17; 66:22). They recognized that righteousness would then prevail (Isa 9:7; 11:4–5; 61:11).

3:14 spotless, blameless. On moral application, see note on v. 11; this behavior contrasts with the immoral teachers (2:13).

3:15 our Lord’s patience. Allows more time for repentance (v. 9), perhaps evoking again the analogy with Noah (vv. 5–7; cf. 1Pe 3:20; Ge 6:3).

3:16 hard to understand. In the ancient world, calling something difficult to understand sometimes implied that it was complex and brilliant. ignorant and unstable people distort. Many teachers interpreted the Scriptures to say what people wanted to hear, sometimes denying future judgment. as they do the other Scriptures. It is very unlikely that all of Paul’s letters in our current NT were already collected by the time of Peter’s death, but Peter would have known of some of them, such as Romans, from places where he traveled. Others cited some letters of Paul as authoritative (1 Clement 47.1, probably by the end of the first century); no less than prophets, apostles could speak by inspiration. More difficult is Peter calling Paul’s letters “Scriptures,” which, in the NT, usually meant the OT. But while some Jewish groups in the first century had a closed canon of Scripture, others, including the authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls and many in the Diaspora, had a fluid idea as to where Scripture ended and other edifying literature began.

3:18 grow in . . . grace and knowledge. Even groups that divided humanity plainly between the righteous/wise and the unrighteous/foolish (cf. Stoics) recognized that the righteous or wise needed to progress in their wisdom or righteousness.