Assignment 2

Strategy – the big picture

Credit for devising the most succinct and usable way to get a handle on the big picture has to be given to Michael E Porter, a professor at Harvard Business School. Porter determined that two factors above all influenced a business’s chances of making superior profits. Firstly there was the attractiveness or otherwise of the industry in which it primarily operated. Secondly, and in terms of an organization’s sphere of influence, more importantly, was how the business positioned itself within that industry.

The five forces theory of industry structure

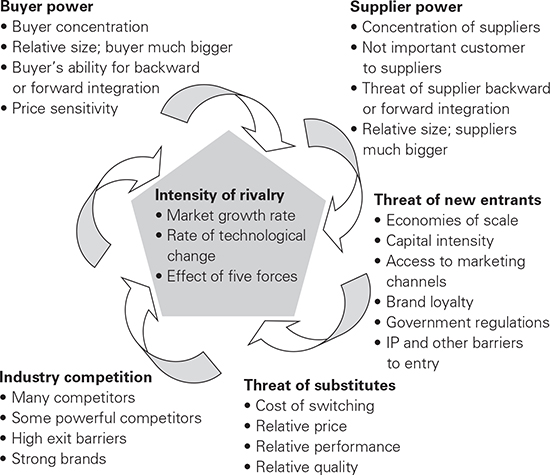

Porter postulated that the five forces that drive competition in an industry have to be understood as part of the process of choosing which strategy to pursue. The forces he identified are:

- Threat of substitution Can customers buy something else instead of your product? For example, Apple, and to a lesser extent Sony, have laptop computers that are distinctive enough to make substitution difficult. Dell on the other hand, faces intense competition from dozens of other suppliers with near-identical products competing mostly on price alone.

- Threat of new entrants If it is easy to enter your market, start-up costs are low, and there are no barriers to entry – such as IP (intellectual property) protection – then the threat is high.

- Supplier power The fewer the suppliers, usually the more powerful they are. Oil is a classic example where fewer than a dozen countries supply the whole market and consequently can set prices.

- Buyer power In the food market, for example, with just a few powerful supermarket buyers being supplied by thousands of much smaller businesses, the supermarkets are often able to dictate terms.

- Industry competition The number and capability of competitors are one determinant of a business’s power. Few competitors with relatively less attractive products or services lower the intensity of rivalry in a sector. Often these sectors slip into oligopolistic behaviour, preferring to collude rather than compete.

Figure 2.1 Five forces theory of industry analysis (after Porter)

You can see a video clip of Professor Porter discussing the five forces model on the Harvard Business School website (http://hbr.org/2008/01/the-five-competitive-forces-that-shape-strategy/ar/1).

Generic strategic options

In Porter’s view a business can only pursue one of three generic strategies (see Figure 2.2) if it is to deliver superior performance. It can have a cost advantage in that it could make a product or deliver a service for less than others. Or it could be different in a way that matters to consumers, so that its offer would be unique, or at least relatively so. Porter added a further twist to his prescription. Businesses could follow either a cost advantage path or a differentiation path industry wide, or they could take a third path – they could concentrate on a narrow specific segment either with cost advantage or differentiation. This he termed ‘focus’ strategy.

Figure 2.2 Strategic options

Start-ups need to pick one of these options only; however, an established venture can pursue different types of strategy for different parts of their business or in different markets.

Cost leadership

Low cost should not be confused with low price. A business with low costs may or may not pass those savings on to customers. Alternatively they could use that position alongside tight cost controls and low margins to create an effective barrier to others considering either entering or extending their penetration of that market. Low-cost strategies are most likely to be achievable in large markets, requiring large-scale capital investment, where production or service volumes are high and economies of scale can be achieved from long runs.

Low costs are not a lucky accident; they can be achieved through these main activities.

- Operating efficiencies New processes, methods of working or less costly ways of working. Ryanair and easyJet are examples where analysing every component of the business made it possible to strip out major elements of cost, meals, free baggage and allocated seating, for example, while leaving the essential proposition – we will fly you from A to B – intact.

- Product redesign This involves rethinking a product or service proposition fundamentally to look for more efficient ways to work, or cheaper substitute materials to work with. The motor industry has adopted this approach with ‘platform sharing’; that is where major players, including Citroen, Peugeot and Toyota, have rethought their entry car models to share major components, which has become common.

- Product standardization A wide range of product and service offers claiming to extend customer choice invariably leads to higher costs. The challenge is to be sure that proliferation gives real choice and adds value. In 2008 the UK railway network took a long hard look at its dozens of different fare structures and scores of names, often for identical price structures, that had remained largely unchanged since the 1960s and reduced them to three basic product propositions. Adopting this and other common standards across the rail network they estimate will substantially reduce the currently excessive £1/2 billion transaction cost of selling £5 billion worth of tickets.

- Economies of scale This can be achieved only by being big or bold. The same head office, warehousing network and distribution chain can support Tesco’s 3,800 stores against the 1,500 that its nearest rival has. Tesco has a lower cost base by virtue of having more outlets to spread its costs over as well as having more purchasing power.

Differentiation

The key to differentiation is a deep understanding of what customers really want and need, and more importantly, what they are prepared to pay more for. Apple’s opening strategy was based around a ‘fun’ operating system based on icons, rather than the dull text of MS-DOS. This belief was based on their understanding that computer users were mostly young and wanted an intuitive command system, and the ‘graphical user interface’ delivered just that. Apple has continued its differentiation strategy, but adds design and fashion to ease of control in the ways in which it delivers extra value. Sony and BMW are also examples of differentiators. Both have distinctive and desirable differences in their products and neither they nor Apple offer the lowest price in their respective industries; customers are willing to pay extra for the idiosyncratic and prized differences embedded in their products.

Differentiation doesn’t have to be confined to just the marketing arena, nor does it always lead to success if the subject of that differentiation goes out of fashion without much warning. Northern Rock, the failed bank that had to be nationalized to stay in business, thought its strategy of raising most of the money it lent out in mortgages through the money markets was a sure winner. It allowed the bank to grow faster than its competitors who place more reliance on depositors for their funds. As long as interest rates were low and the money market functioned smoothly it worked. But once the differentiators that fuelled its growth were reversed, its business model failed.

Focus

Focused strategy involves concentrating on serving a particular market or a defined geographic region. IKEA, for example, targets young, white-collar workers as its prime customer segment, selling through 235 stores in more than 30 countries. Ingvar Kamprad, an entrepreneur from the Småland province in southern Sweden, who founded the business in the late 1940s, offers home furnishing products of good function and design at prices young people can afford. He achieves this by using simple cost-cutting solutions that do not affect the quality of products.

Warren Buffett, the world’s richest man, who knows a thing or two about focus, combined with Mars to buy US chewing gum manufacturer Wrigley for US$23 billion (£11.6 billion/€13.2 billion) in May 2008. Chicago-based Wrigley, which launched its Spearmint and Juicy Fruit gums in the 1890s, has specialized in chewing gum ever since and consistently outperformed its more diversified competitors. Wrigley is the only major consumer products company to grow comfortably faster than the population in its markets and above the rate of inflation. Over the past decade or so, for example, other consumer products companies have diversified. Gillette moved into batteries used to drive many of its products by acquiring Duracell. Nestlé bought Ralston Purina, Dreyer’s, Ice Cream Partners and Chef America. Both have trailed Wrigley’s performance.

Businesses often lose their focus over time and periodically have to rediscover their core strategic purpose. Procter & Gamble is an example of a business that had to refocus to cure weak growth. In 2000, the company was losing share in seven of its top nine categories, and had lowered earnings expectations four times in two quarters. This prompted the company to restructure and refocus on its core business; big brands, big customers, and big countries. They sold off non-core businesses, establishing five global business units with a closely focused product portfolio.

CASE STUDY Specsavers

Every once in a while an entrepreneur turns an industry on its head. Dame Mary Perkins is a perfect example. When she launched her business it changed the face of optometry for good. We might be used to visiting showrooms to purchase glasses these days, trying on frames at our leisure until we find the perfect fit, with every item clearly priced, but back in the early 1980s this was not the case. Before Mary launched Specsavers, consumers had very little choice or control when purchasing eyewear. Indeed, before Specsavers came along, when you visited an optician they’d disappear out back to find a few pairs for you to try on. But Mary had a clear vision of how opticians could operate in order to deliver better value, choice and transparency to consumers. Driven by a mission of providing affordable eyecare to all, she built the company around the idea of treating others respectfully. She still describes her billion-pound international company, which she founded with her husband, Doug Perkins, as ‘a family-owned business, with family values’.

One of the key lessons Mary learnt early on was the importance of setting yourself apart from the competition. As a new business, there was no point in merely copying a major player – you had to offer customers something different. She identified a number of major problems with the way opticians were doing business at the time, and came up with a proposition that she felt was far more attractive to consumers. First of all, glasses were expensive. Mary believed that she would be able to bring prices down without compromising on quality by negotiating better buying terms and selling larger volumes. For example, instead of buying from wholesalers who added a significant mark-up on their prices, she went to factories directly.

From just two staff working at a table-tennis table, there are now more than 500 based at Specsavers’ headquarters in Guernsey and around 26,000 worldwide. The company has more than 1,390 stores across the Channel Islands, the UK, Ireland, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, Spain, Australia and New Zealand. Mary believes that much of her success has been driven by the preservation of the founding culture and ideals, and a focus on giving consumers real value and choice.

Strategic framework

The strategic framework shown in Figure 2.3 should put the whole strategic process clearly in view and help you to formulate a clear course of action.

Figure 2.3 Elements of a business strategy

The foundation of this process is a clear statement of the mission of your venture, your objectives and the geographic limits you have set yourself, at least for the time being. These issues were addressed in the first assignment and until they are satisfactorily resolved, no meaningful strategy can be evolved.

Market research data are then gathered on customers, competitors and the business environment, for example, to confirm that your original perception of your product or service is valid. More than likely this research will lead you to modify your product in line with this more comprehensive appreciation of customer needs. You may also decide to concentrate on certain specific customer groups. Information on competitors’ prices, promotional methods and location/distribution channels should then be available to help you to decide how to compete.

No business can operate without paying some regard to the wider economic environment in which it operates. So a business plan must pay attention to factors such as:

- The state of the economy and how growth and recession are likely to affect such areas as sales, for example. During a time of economic recession, start-ups sometimes benefit from increased availability of premises, second-hand equipment etc, and find they develop sales strongly as the economy and markets recover. For example, Cranfield MBA Robert Wright developed ConnectAir at the end of one recession and was able to sell to Air Europe at the height of the Lawson boom – a trick that he subsequently repeated for 10 times that value (£75 million) a decade later!

- Any legislative constraints or opportunities. One Cranfield enterprise programme participant’s entire business was founded solely to exploit recent laws requiring builders and developers to eliminate asbestos from existing properties. His business was to advise them how to do so.

- Any changes in technology or social trends that may have an impact on market size or consumer choice. For example, the increasing number of single-parent families may be bad news at one level, but it’s an opportunity for builders of starter unit housing. And the increasing trend of wives returning to work is good news for convenience food sales and restaurants.

- Any political pressures, either domestic or pan-European, that are likely to affect your business. An example was New Labour’s law against late payment of bills. The government’s aim was to help small firms get paid more quickly by large firms. However, experience elsewhere, where such legislation is in force, showed clearly that large firms simply alter their terms of trade. In that way many small firms actually ended up taking longer to collect money owed them, rather than just the unlucky or the inefficient ones.

CASE STUDY Georgia Chopsticks – sold in China, marked: ‘Made in USA’

Cost advantage-based strategies – certainly when it comes to selling into advanced economies such as the United States – have, until now at least, been the prerogative of Chinese enterprises. But one American company could be about to reverse that trend. While over 60 billion sets of chopsticks are produced every year in China to meet the needs of their increasingly affluent population, there still are not enough to go round. This Far East chopstick crisis has arisen because of a shortage of the right type of wood in China. Step forward Jae Lee, a Korean-American who launched his chopstick exporting business in Americus, Georgia. This town of 17,000 people about a two-hour drive south from Atlanta has two big advantages: high unemployment and an abundant supply of sweet gum trees, the ideal raw material for making chopsticks. These gum trees grow like weeds around Americus and are hard enough to work as chopsticks, but not so hard as to dull the blades used to cut the wood.

By August 2011 the business was operating 24/7, with the Americus plant producing two million chopsticks a day. The chopsticks are destined for supermarket chains in China, companies in Japan and Korea, with the smallest portion of their business retained in the United States.

SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats)

The process by which all these data are examined is called the SWOT analysis: your company’s strengths and weaknesses are analysed and compared with the perceived environment, opportunities and threats. Its purpose is to allow you to develop a strategy using areas in which you are more able than the competition to meet the needs of particular target customer groups.

Our experience with new starters at Cranfield has emphasized the importance for the small company of the second and third of these generic strategies, sometimes judiciously mixed, particularly bringing into play the four major elements of the marketing mix (product, price, promotion and place) to emphasize your differentiation and focus.

Many new start-ups at the turn of the millennium sought to benefit from the newly available internet technology and vigorously pursued a cost leadership strategy. The low margins often implicit in this strategy left little room for manoeuvre when things went awry. For example, Cranfield MBA Dexter Kirk, with 12 traditional clothing stores, noted: ‘My heart is only gladdened by the final reality that has set in on dot.com apparel marketing. Funny, we old lags called it “mail order” and knew that you should allow for 30 per cent returns. When I told Boo.com that at a meeting before Christmas, they thought I was mad. I also warned my daughter who is in dotcom PR that “brown boxes” would be the problem, ie fulfilment is the most unsexy part of the job. Sure enough, one of her B2C clients delivered all their Christmas trees on January 5th!’

Needless to say, neither company survived. Hence the need to emphasize differentiation and focus with better margins in the early learning phase of start-up and business growth.

First-to-market fallacy

‘Gaining first mover advantage’ are words used like a mantra to justify skipping the industry analysis and strategy formulation stages in preparing a business plan. This myth is one of the most enduring in business theory and practice. Entrepreneurs and established giants are always in a race to be first, believing that it is necessary for success. Research from the 1980s which showed that market pioneers had enduring advantages in distribution, product-line breadth, product quality and, especially, market share, underscored this principle.

Beguiling though the theory of first-mover advantage is, it is probably wrong. Gerard Tellis, of the University of Southern California, and Peter Golder, of New York University’s Stern business school, argued in their book, Will and Vision: How latecomers grow to dominate markets (2001, McGraw-Hill Inc, US) and subsequent research, that previous studies on the subject were deeply flawed. In the first instance earlier studies were based on surveys of surviving companies and brands, excluding all the pioneers that failed. This helps some companies to look as though they were first to market even when they were not. Procter & Gamble (P&G) boasts that it created America’s disposable-nappy (diaper) business. In fact, a company called Chux launched their product a quarter of a century before P&G entered the market in 1961.

Also, the questions used to gather much of the data in earlier research were at best ambiguous, and perhaps dangerously so. For example the term ‘one of the pioneers in first developing such products or services’ was used as a proxy for ‘first to market’. The authors emphasize their point by listing popular misconceptions of who were the real pioneers across the 66 markets they analysed. Online book sales – Amazon (wrong), Books.com (right); Copiers – Xerox (wrong), IBM (right); PCs – IBM/Apple (both wrong). Micro Instrumentation Telemetry Systems (MITS) introduced its PC, the Altair, a US$400 kit, in 1974, followed by Tandy Corporation (Radio Shack) in 1977.

In fact the most compelling evidence from all the research was that nearly half of all firms pursuing a first-to-market strategy were fated to fail, while those following fairly close behind were three times as likely to succeed. Tellis and Golder claim the best strategy is to enter the market 19 years after pioneers, learn from their mistakes, benefit from their product and market development and be more certain about customer preferences.

Vision

A vision is about stretching the organization’s reach beyond its grasp. Few now can see how the vision can be achieved, but can see that it would be great if it could be. Microsoft’s vision of a computer in every home, formed when few offices had one, is one example of a vision that has nearly been reached. Stated as a company goal back in 1990, it might have raised a wry smile: after all it was only a few decades before then that IBM had estimated the entire world demand for its computers as seven! Their updated vision to ‘Create experiences that combine the magic of software with the power of Internet services across a world of devices,’ is rather less succinct! Apple, Microsoft’s arch rival, has the vision to: ‘make things that make an impact’. They do this by using the latest technology, investing in packaging and design, making their products easier to use and more elegant than anything else around, and selling them at a premium price. Personal computers, music players, smartphones and tablet computers – and now cloud-based services – have all been treated to the Apple visionary touch with considerable success. By 2011 Apple overtook Microsoft in terms of its stock market value.

Ocado, the online grocer floated on the stock market in 2010, was established with a clear vision: to offer busy people an alternative to going to the supermarket every week. IBM’s vision is to package technology for use by businesses. Starting out with punch-card tabulators, IBM adapted over its 100 years+ history to supply magnetic-tape systems, mainframes, PCs, and consulting (since it bought the consulting arm of PricewaterhouseCoopers, an accounting firm, in 2002). Building a business around a vision, rather than a specific product or technology, makes it easier to get employees, investors and customers to buy into a long-term commitment to a business, seeing they could have opportunities for progression in an organization that knows where it is going.

Mission

A mission is a direction statement, intended to focus your attention on the essentials that encapsulate your specific competence(s) in relation to the market/customers you plan to serve. First, the mission should be narrow enough to give direction and guidance to everyone in the business. This concentration is the key to business success because it is only by focusing on specific needs that a small business can differentiate itself from its larger competitors. Nothing kills off a business faster than trying to do too many different things too soon. Second, the mission should open up a large enough market to allow the business to grow and realize its potential. You can always add a bit on later. In summary, the mission statement should explain:

- what business you are in and your purpose;

- what you want to achieve over the next one to three years, ie your strategic goal.

Above all, mission statements must be realistic, achievable – and brief.

Toys R Us has as its mission ‘To be the world’s greatest kids’ brand’; Starbucks is to ‘To inspire and nurture the human spirit – one person, one cup and one neighbourhood at a time’. Neither of those missions says anything about products or services; rather they are focused on customer groups – kids for Toys R Us and on needs for Starbucks; both are areas that are likely to be around for a while yet. Nestlé’s mission is captured in these words: ‘Good Food, Good Life’. Their claim here is to provide consumers with the best tasting, most nutritious choices in a wide range of food and beverage categories and eating occasions, from morning to night.

Amazon’s mission – ‘We seek to be Earth’s most customer-centric company for three primary customer sets: consumer customers, seller customers and developer customers’ – though punchy enough, doesn’t provide much guidance to the rank and file on what to do every day.

Values

A business faces tough choices every day and the bigger it gets the greater the number of people responsible for setting out what you ultimately stand for – profits alone, or principled profits. Defining your values will make it possible for everyone working for you to know how to behave in any situation. Your values should be seen to run through the business – a common thread touching every decision. Southwest Airlines, the first and arguably the best low-cost airline, has cultivated a reputation for being the ‘nice’ airline. A past CEO, James Parker, tells a story that sums up their values (‘we want people to consistently do the right thing because they want to’): One evening flight landed in Detroit and all the passengers, bar one, a young girl, disembarked. She should have got off at Chicago, an earlier stop, but failed to do so. Despite this being the night before Thanksgiving, the pilot and crew knew they had to get the passenger back to her anxious parents. Without asking for company permission they just took off and returned the girl to her correct destination. They knew what should be done, regardless of the additional cost and inconvenience, and just got on with it.

CASE STUDY Toys R Us

Toys R Us have what they call their ‘R’ Values – ‘At Toys R Us, Inc., we believe that by being rapid, real, reliable and responsible, we will best serve our customers, employees, shareholders, communities and kids!’

- Rapid: We believe that speed is a reflection of our culture. Our team is focused and clear with common, user-friendly processes and solutions; fast and urgent in decision-making and speed-to-market; and quick in adapting to change.

- Real: Our team is urgent, sincere, authentic, helpful to work with and confident. We are ‘Playing to Win!’

- Reliable: Being reliable means working as a team so everything can move faster. We are a company that is dependable, and we produce what we promise.

- Responsible: We believe that honesty, integrity and compassion are the foundation upon which we work together and conduct our business. Keeping kids safe is a cornerstone of the brand.

As a company, and as individuals, we value integrity, honesty, openness, personal excellence, constructive self-criticism, continual self-improvement, and mutual respect. We are committed to our customers and partners and have a passion for technology. We take on big challenges, and pride ourselves on seeing them through. We hold ourselves accountable to our customers, shareholders, partners, and employees by honouring our commitments, providing results, and striving for the highest quality.

Objectives

The milestones on the way to realizing the vision and mission are measured by the achievement of business objectives. Your business plan should set out the primary goals in terms of profit, turnover and business value, particularly if you want to attract outside investment. Pizza Express, for example, set out its goal as aiming to nearly double their number of outlets from 318 to 700 by 2020. Majestic Wine announced a similar-sounding goal, aiming to add 12 new stores a year for the coming ten years.

Make sure that your business plan contains SMART objectives:

- Specific: Relate to specific tasks and activities, not general statements about improvements.

- Measurable: It should be possible to assess whether or not they have been achieved.

- Attainable: It should be possible for the employee to achieve

- the desired outcome.

- Realistic: Within the employee’s current or planned-for capability.

- Timed: To be achieved by a specific date.