Assignment 4

Researching customers

Without customers no business can get off the ground, let alone survive. Some people believe that customers arrive after the firm ‘opens its doors’. This is nonsense. You need a clear idea in advance of who your customers will be, as they are a vital component of a successful business strategy, not simply the passive recipients of new products or services.

Knowing something about your customers and what you plan to sell to them seems so elementary it is hard to believe that any potential business-person could start a business without doing so. But it is all too common, and one of the reasons many new businesses fail.

Recognizing customer needs

The founder of a successful cosmetics firm, when asked what he did, replied, ‘In the factories we make perfume, in the shops we sell dreams.’

Those of us in business usually start out defining our business in physical terms. Customers on the other hand see businesses having as their primary value the ability to satisfy their needs. Even firms that adopt customer satisfaction, or even delight, as their maxim often find it a more complex goal than it at first appears. Take Blooming Marvellous by way of an example. It made clothes for the mother-to-be, sure enough: but the primary customer need it was aiming to satisfy was not either to preserve their modesty or to keep them warm. The need it was aiming for was much higher: it was ensuring its customers would feel fashionably dressed, which is about the way people interact with each other and how they feel about themselves. Just splashing a tog rating showing the thermal properties of the fabric, as you would with a duvet, would cut no ice with the Blooming Marvellous potential market.

Until you have clearly defined the needs of your market(s) you cannot begin to assemble a product or service to satisfy them.

CASE STUDY Ella’s Kitchen

Paul Lindley had no experience of either the industry his business started up in or indeed of running his own business. Lindley, aged 50, was a UK director of Nickelodeon, the cable children’s television channel, and starting up dealing with the UK’s big supermarket chains looked like an ambitious project to embark on.

His idea for baby food in squeezy pouches was triggered by the problems in trying to get his own daughter, Ella, to eat food when they were travelling. Until he launched Ella’s the majority of baby food was sold in glass jars for the compelling reason than parents wanted to see the food before they bought it. But feeding children from a jar meant that parents had to take control of the feeding process, not something that many young children readily buy into. Lindley’s idea was to use pouches like the ones he had seen sold in French supermarkets, aimed at adults and mostly containing mayonnaises and salad dressings. He reckoned that with children’s foods served up in this way kids could hold onto the pouches and feed themselves, making feeding on the go in particular a much easier proposition than with a jar and spoon.

There were a number of other major advantages in using pouches over plain glass bottles. In the first place packaging the product in this way is aimed at the actual consumer – babies and toddlers – not the parents buying the food. So rather than being clear, the packaging is brightly coloured, covered in cartoon-style drawings – and named after his daughter. Also food in pouches can be delivered in pasteurized form rather than having to be sterilized at high temperatures. That in turn means the food retains colour, taste, texture, vitamins more than you would otherwise, so is actually a healthier option.

Ella’s Kitchen must be meeting customers’ needs – turnover in 2016–17 was over £80 million and their pouches are sold in supermarkets internationally including UK, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Canada and the United States.

Fortunately help is at hand when it comes to getting an inside track on your customers’ thought process. The US psychologist Abraham Maslow demonstrated in his research that ‘all customers are goal seekers who gratify their needs by purchase and consumption’. He then went a bit further and classified consumer needs into a five-stage pyramid he called the hierarchy of needs:

- Self-actualization. This is the summit of Maslow’s hierarchy in which people are looking for truth, wisdom, justice and purpose. It’s a need that is never fully satisfied, and according to Maslow only a very small percentage of people ever reach the point where they are prepared to pay much money to satisfy such needs. It is left to the like of Bill Gates and Sir Tom Hunter to give away billions to form foundations to dispose of their wealth on worthy causes. The rest of us scrabble around further down the hierarchy.

- Esteem. Here people are concerned with such matters as self-respect, achievement, attention, recognition and reputation. The benefits customers are looking for include the feeling that others will think better of them if they have a particular product. Much of brand marketing is aimed at making consumers believe that conspicuously wearing the maker’s label or logo so that others can see it will earn them ‘respect’. Understanding how this part of Maslow’s hierarchy works was vital to the founders of Responsibletravel.com (www.responsibletravel.com). Founded in 2001 with backing from Anita Roddick (Body Shop) in Justin Francis’s front room in Brighton, with his partner Harold Goodwin he set out to create the world’s first company to offer environmentally responsible travel and holidays. It was one of the first companies to offer carbon offset schemes for travellers, and Responsibletravel.com boast that they turn away more tour companies trying to list on their site than they accept. They appeal to consumers who want to be recognized in their communities as being socially responsible. In 2010 they launched their US business, Responsible Vacation, and now have over 350 specialist tour operators on their books.

- Social needs. The need for friends, belonging to associations, clubs or other groups and the need to give and get love are all social needs. After ‘lower’ needs have been met, these needs that relate to interacting with other people come to the fore. Hotel Chocolat (www.hotelchocolat.co.uk), founded by Angus Thirlwell and Peter Harris in their kitchen, is a good example of a business based on meeting social needs. They market home-delivered luxury chocolates but generate sales by having ‘tasting clubs’ to check out products each month. The concept of the club is that you invite friends round and using the firm’s scoring system, rate and give feedback on the chocolates.

- Safety. The second most basic need of consumers is to feel safe and secure. People who feel they are in harm’s way either through their general environment or because of the product or service on offer will not be over interested in having their higher needs met. When Charles Rigby set up World Challenge (www.world-challenge.co.uk) to market challenging expeditions to exotic locations around the world with the aim of taking young people up to around 19 years old out of their comfort zones and teaching them how to overcome adversity, he knew he had a challenge of his own on his hands: how to make an activity simultaneously exciting and apparently dangerous to teenagers, while being safe enough for the parents writing the cheques to feel comfortable. Six full sections on the website are devoted to explaining the safety measures the company takes to ensure that unacceptable risks are eliminated as far as is humanly possible.

- Physiological needs. Air, water, sleep and food are all absolutely essential to sustain life. Until these basic needs are satisfied higher needs such as self-esteem will not be considered.

You can read more about Maslow’s needs hierarchy and how to take it into account in understanding customers on the MBA website (www.netmba.com>Management>Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs).

Segmenting the market

That customers have different needs means that we need to organize our marketing effort so as to address those individually. However, trying to satisfy everyone may mean that we end up satisfying no one fully. The marketing process that helps us deal with this seemingly impossible task is market segmentation. This is the name given to the process whereby customers and potential customers are organized into clusters or groups of ‘similar’ types. For example, a carpet/upholstery cleaning business has private individuals and business clients running restaurants and guest houses as its clients. These two segments are fundamentally different, with one segment being more focused on cost and the other more concerned that the work is carried out with the least disruption to the business. Also, each of these customer groups is motivated to buy for different reasons, and the selling message has to be modified accordingly.

These are some of the ways by which markets can be segmented:

- Psychographic segmentation divides individual consumers into social groups such as ‘Yuppies’ (young, upwardly

mobile professionals), ‘Bumps’ (borrowed-to-the-hilt, upwardly mobile, professional

show-offs) and ‘Jollies’ (jet-setting oldies with lots of loot). These categories

try to show how social behaviour influences buyer behaviour. Forrester Research, an

internet research house, claims when it comes to determining whether consumers will

or will not go on the internet, how much they will spend and what they will buy, demographic

factors such as age, race, and gender don’t matter anywhere near as much as the consumers’

attitudes towards technology. Forrester uses this concept, together with its research, to produce Technographics® market segments as an aid to understanding consumers’ behaviour as digital consumers

(www.forrester.com>research & data>consumer technographics).

Forrester has used two categories: technology optimists and technology pessimists, and has used these alongside income and what it calls ‘primary motivation’ – career, family and entertainment – to divide up the whole market. Each segment is given a new name – ‘Techno-strivers’, ‘Digital Hopefuls’ and so forth – followed by a chapter explaining how to identify them, how to tell whether they are likely to be right for your product or service and providing some pointers as to what marketing strategies might get favourable responses from each group.

- Benefit segmentation recognizes that different people can get different satisfaction from the same product or service. Lastminute.com claims two quite distinctive benefits for its users. First, it aims to offer people bargains that appeal because of price and value. Second, the company has recently been laying more emphasis on the benefit of immediacy. This idea is rather akin to the impulse-buy products placed at checkout tills, which you never thought of buying until you bumped into them on your way out. Whether 10 days on a beach in Goa or a trip to Istanbul are the types of things people ‘pop in their baskets’ before turning off their computers, time will tell.

- Geographic segmentation arises when different locations have different needs. For example, an inner-city location may be a heavy user of motorcycle dispatch services, but a light user of gardening products. However, locations can ‘consume’ both products if they are properly presented. An inner-city store might sell potatoes in 1 kg bags, recognizing that its customers are likely to be on foot. An out-of-town shopping centre may sell the same product in 20 kg sacks, knowing its customers will have cars.

- Industrial segmentation groups together commercial customers according to a combination of their geographic location, principal business activity, relative size, frequency of product use, buying policies and a range of other factors.

- Multivariant segmentation is where more than one variable is used. This can give a more precise picture of a market than using just one factor.

These are some useful rules to help decide whether a market segment is worth trying to sell into:

- Measurability. Can you estimate how many customers are in the segment? Are there enough to make it worth offering something ‘different’?

- Accessibility. Can you communicate with these customers, preferably in a way that reaches them on an individual basis? For example, you could reach the over-50s by advertising in a specialist ‘older people’s’ magazine with reasonable confidence that young people will not read it. So if you were trying to promote Scrabble with tiles 50 per cent larger, you might prefer that young people did not hear about it. If they did, it might give the product an old-fashioned image.

- Open to profitable development. The customers must have money to spend on the benefits that you propose to offer.

- Size. A segment has to be large enough to be worth your exploiting it, but perhaps not so large as to attract larger competitors.

Segmentation is an important marketing process, as it helps to bring customers more sharply into focus, and it classifies them into manageable groups. It has wide-ranging implications for other marketing decisions. For example, the same product can be priced differently according to the intensity of customers’ needs. The first- and second-class post is one example, off-peak rail travel another. It is also a continuous process that needs to be carried out periodically, for example when strategies are being reviewed.

Business to Business (B2B) buyer criteria

There is a popular theory that business buyers are hard-nosed, cold-hearted Scrooges, making entirely rational choices with the sole goal of doing the best they can for their shareholders. If this were really the case an awful lot of promotional gift suppliers would be out of business. Pharmaceutical companies could fire their sales forces, slashing costs by billions. All doctors and pharmacists would have to do is read up the research proof on drugs and prescribe accordingly. That probably wouldn’t take any more time than listening to a rep make their pitch.

At the end of the day, people buy from people and that’s where Maslow’s needs swing back into play. ‘No one ever got fired buying IBM’ was a much-quoted phrase in buying departments in the days when IBM’s main business was selling computers. This simply meant that the buyer could feel secure in making that decision, as IBM’s reputation was high. Buying anywhere else, even if the specification was better and the price lower, was personally risky. IBM’s sales force could use the buyer’s need to feel safe to great advantage in their presentations.

When understanding the needs of business buyers it is important to keep in mind that there are at least three major categories of people who have a role to play in the B2B buying decision and so whose needs have to be considered in any analysis of a business market.

The user, or end customer

This is the recipient of any final benefits associated with the product or service, much as with an individual consumer. Functionality will be vital for this group.

The specifier

Though specifiers may not use or even see their purchases, they will want to be sure the end users’ needs are met in terms of performance, delivery and any other important parameters. Their ‘customer’ is both the end user and the budget holder of the cost centre concerned. There may even be conflict between the two (or more) ‘customer’ groups. For example, in the case of, say, hotel toiletries, those responsible for marketing the rooms will want high-quality products to enhance their offer – while the hotel manager will have cost close to the top of their concerns, and the people responsible for actually putting the product in place will be interested mostly in any handling and packaging issues.

The non-consuming buyer

This is the person who actually places the order. They will be basing their decision on a specification drawn up by someone else, but they will also have individual needs. Some of their needs are similar to those of a specifier, except they will have price at – or near – the top of their needs.

CASE STUDY Flowcrete

In just 18 years, Dawn Gibbins MBE, co-founder of Flowcrete (www.flowcrete.com), took the company from a 400 sq ft unit (the size of a double garage) with £2,000 capital to a plc with a turnover of €52 million in the field of floor screeding technology, and clients including household names such as Cadbury, Sainsbury’s, Unilever, Marks & Spencer, Barclays and Ford. Part of Flowcrete’s success was down to a continuing focus on technical superiority. This attribute was engendered by Dawn’s father, a well-respected industrial chemist with an interest in resin technology.

But arguably Dawn’s skills contributed as much if not more to the firm’s success. ‘We want to be champions of change,’ Gibbons claims. ‘We have restructured a dozen times, focusing on new trends.’ Markets and market segmentation are a vital part of any restructuring process – indeed, the best companies restructure around their customers’ changing needs.

The first reappraisal came after seven years in business when Flowcrete realized that its market was no longer those firms that laid floors; it now had to become an installer itself. Changes in the market meant that to maintain growth Flowcrete had to appoint proven specialist contractors, train their staff, write specifications and carry out audits to ensure quality. The business now has a global presence.

The largest, most visited shopping centre in the world, the Dubai Mall, used over 540,000m2 of Flowcrete’s Deckshield carpark decking to refurbish its huge parking facility.

Defining the product in the customers’ terms

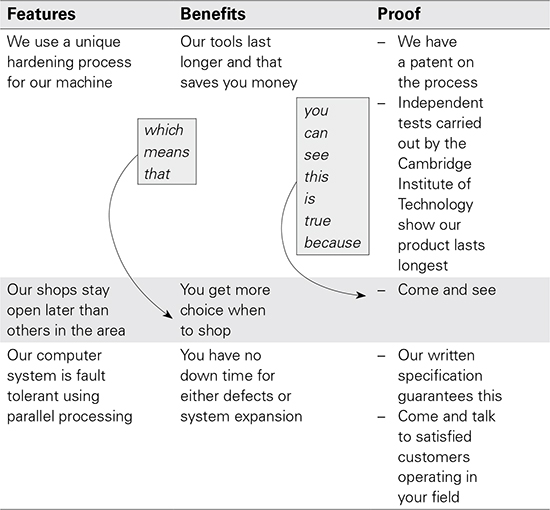

Once you know what you are selling and to whom, you can match the features of the product (or service) to the benefits customers will get when they purchase. Features are what a product has or is, and benefits are what the product does for the customer. For example, cameras, SLR or lens shutters, even film are not the end product that customers want; they are looking for good pictures. Finally, as in Table 4.1, include ‘proof’ that these benefits can be delivered.

Table 4.1 Example showing product features, benefits and proof

Remember, the customer pays for the benefits and the seller for the features. So the benefits will provide the ‘copy’ for most of your future advertising and promotional efforts.

Who will buy first?

Customers do not sit and wait for a new business to open its doors. Word spreads slowly as the message is diffused throughout the various customer groups. Even then it is noticeable that generally it is the more adventurous types who first buy from a new business. Only after these people have given their seal of approval do the ‘followers’ come along. Research shows that this adoption process, as it is known, moves through five distinct customer characteristics, from ‘innovators’ to ‘laggards’, with the overall population being different for each group (see Table 4.2).

Table 4.2 The product/service adoption cycle

|

Innovators |

2.5% of the overall market |

|

Early adopters |

13.5% of the overall market |

|

Early majority |

34.0% of the overall market |

|

Late majority |

34.0% of the overall market |

|

Laggards |

16.0% of the overall market |

|

Total market |

100% |

Let’s suppose you have identified the market for your internet gift service. Initially your market has been constrained to affluent professionals within 5 miles of your home to keep delivery costs low. So if market research shows that there are 100,000 people that meet the profile of your ideal customer and they have regular access to the internet, the market open for exploitation at the outset may be as low as 2,500, which is the 2.5 per cent of innovators.

This adoption process, from the 2.5 per cent of innovators who make up a new business’s first customers, through to the laggards who won’t buy from anyone until they have been in business for 20 years, is most noticeable with truly innovative and relatively costly goods and services, but the general trend is true for all businesses. Until you have sold to the innovators, significant sales cannot be achieved, so an important first task is to identify these customers. The moral is: the more you know about your potential customers at the outset, the better your chances of success.

One further issue to keep in mind when shaping your marketing strategy is that innovators, early adopters and all the other sub-segments don’t necessarily use the same media, websites, magazines and newspapers, or respond to the same images and messages. So they need to be marketed to in very different ways.

At the minimum, your business plan should include information on:

- Who your principal customers are or, if you are launching into new areas, who they are likely to be. Determine in as much detail as you think appropriate the income, age, sex, education, interests, occupation and marital status of your potential customers, and name names if at all possible.

- What factors are important in the customer’s decision to buy or not to buy your product and/or service, how much they should buy and how frequently?

- Many factors probably have an influence, and it is often not easy to identify all

of them. These are some of the common ones that you should consider investigating:

- Product considerations

- price

- quality

- appearance (colour, texture, shape, materials, etc)

- packaging

- size

- fragility, ease of handling, transportability

- servicing, warranty, durability

- operating characteristics (efficiency, economy, adaptability, etc).

- Business considerations

- location and facilities

- reputation

- method(s) of selling

- opening hours, delivery times, etc

- credit terms

- advertising and promotion

- variety of goods and/or services on offer

- Appearance and/or attitude of company’s property and/or employees

- Capability of employees.

- Other considerations

- weather, seasonality, cyclicality

- changes in the economy – recession, depression, boom.

- Product considerations

CASE STUDY Victoria’s Secret

Roy Raymond, an alumnus of Tufts University, took his MBA at Stanford Graduate School of Business. He opened his first Victoria’s Secret store in 1977 at the Stanford Shopping Centre with an $80,000 loan, half provided by a bank and the remainder borrowed $40,000 from relatives. It was an immediate success, exceeding $500,000 sales in its first trading year. The first UK store opened in August 2012 in London’s New Bond Street.

Victoria’s Secret is the number one intimate apparel brand in the USA, with around 1,600 shops worldwide, one of the most visited websites dating back to 1998 and over 400 million copies of their catalogue are distributed annually. The company rode out the post-2008 downturn with relative ease. In 2014 in less-than-great economic conditions sales at Victoria’s Secret Stores and Victoria’s Secret Beauty and Victoria’s Secret Direct grew 10 per cent and 3 per cent respectively. Gross profit climbed 5 per cent to $945.3 million, gross margin pushed up 270 basis points to 39.4 per cent. Operating income nudged up 1 per cent to $308.9 million and the operating margin moved up to a healthy 12.9 per cent, a near best for the sector. Times have proved rather tougher in 2017 with like-for-like sales dipping from the previous year. However they are still the star turn in their parent company, L Brands, Inc., who reported $951.4 million turnover for the five weeks ended 1 April 2017.

So what’s the secret of Victoria’s success? The business was founded, so the story goes, out Raymond’s embarrassment at trying to buy lingerie for his wife in the less-than-comfortable environment of a public shopping floor in a department store. Without men, Raymond reckoned, the lingerie business was missing out on half its potential customer base. Men were in fact a major untapped market segment. Men, he reckoned, would be more comfortable if the decor of the stores were along the lines of a Victorian drawing room, complete with Oriental rugs and antique armoires housing lingerie displays. The business’s name was inspired by the period of the home that Roy and his wife Gaye were living in at the time. Friendly and inviting staff went out of their way to make purchasing lingerie a unembarrassing, (almost) normal event.

In 1982 Raymond sold the Victoria’s Secret company together with its six stores and 42-page catalogue, grossing $6 million per year, to Leslie Wexner, founder of The Limited, for $4 million. Wexner who had taken Limited Brands public in 1977, listed as LTD on the NYSE, was on an acquisition spree. He went on to buy Lane Bryant stores, then in 1985, a single Henri Bendel store was purchased for $10 million, 798 Lerner stores for $297 million and finally in 1988, 25 Abercrombie & Fitch stores were added to the portfolio for $46 million. This represented the high water mark for Wexner, who sold out to the venture capital firm Sun Capital Partners Inc. in stages, completing his exit in 2010.

Victoria’s Secret was founded on a simple demographic market segmentation criteria: the sex of the buyer, not the user. The company today still segments its market demographically, but in much greater detail. They knows the age, gender, income and social class of their target market in every area in which they operate and deliver specific messages, refining their strategy along the way.

A case study on the company, prepared by Theodore Durbin, an MBA Fellow at the Centre for Digital Strategies at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth under the supervision of Adjunct Professor Kathleen L Biro, reviewed how Victoria’s Secret went about gathering data to help it segment markets. They developed, Durbin noted, ‘a sophisticated algorithm called Recency, Frequency, and Monetary Value (RFM), based on the theory that recent shoppers were more responsive to catalogue mailings, as were more frequent shoppers and those with higher recent order sizes. The RFM algorithm used each customer’s transaction history to determine which customers should receive the largest number of mailings based on their calculated propensity to buy as evidenced by their scores across each of those variables.’

Durbin’s study noted that the company went well beyond RFM, adopting sophisticated mathematical modelling to segment prospects and current customers. There were, Durbin observed,

models for customer acquisition, retention and extension. Each segment had different profiles and costs, and it was a difficult balancing g act to set priorities by segment. For example, although it cost $20 to acquire a new customer and only $10 to reactivate a previous customer, attracting ‘new to file’ customers was important for the long-term health of the business, despite the increased costs, as customers in any direct business were always ‘rolling off the file’. In addition, 10 per cent of the customer file generated 50 per cent of the business, so it was also important to cultivate heavy buyers.

- Since many of these factors relate to the attitudes and opinions of the potential

customers, it is likely that answers to these questions will only be found through

interviews with customers. It is also important to note that many factors that affect

buying are not easily researched and are even less easy to act upon. For example,

the amount of light in a shop or the position of a product on the shelves can influence

buying decisions.

You could perhaps best use the above list to rate what potential customers see as your strengths and weaknesses. Then see if you can use that information to make your offering more appealing to them.

- As well as knowing something of the characteristics of the likely buyers of your product or service, you also need to know how many of them there are, and whether their ranks are swelling or contracting. Overall market size, history and forecasts are important market research data that you need to assemble – particularly data that refer to your chosen market segments, rather than just to the market as a whole.

CASE STUDY dunnhumby

Clive and Edwina, founders of dunnhumby came up with their entire business proposition based on providing segmented data on markets. Their concept involved retaining and analysing customer data based on behaviour, which would enable companies to deliver marketing that was more relevant to their customers. They approached their employer with the idea but they were not willing to invest their profits in this new concept. Clive was adamant this idea should be pursued and his disappointment in the company’s lack of vision led him to resign from the business in order to pursue the vision on his own. As Edwina, who was married to him, recalls, ‘I was literally fired 10 minutes later as they felt I would be competing with their business.’ She received a substantial payout – enough to dissuade her from claiming unfair dismissal. The result was a new player in the market, dunnhumby, which left CACI playing catch-up in a market they could have dominated from the outset.

Undoubtably the company made its mark when it took on Tesco as a client. The top handful of multinational retailers, Walmart, Metro, Groupe Carrefour, Ahold and Tesco all slug it out around the globe with the all-important aim of capturing a few additional percentage points of market share. To win that extra share retailers have to know more about their markets than their competitors. Tesco’s growth in stores in the early years was more art than science. But to be absolutely fair the other retailers operated in much the same way. Jack Cohen, Tesco’s founder based his initial strategy on operating from market stalls which made it easy, cheap and quick to follow his customers rather than requiring them to come to him. But if you want the customers to come to you the strategy has to be based more on science than art. A 130,000 sq ft supermarket costs around £45 million to build and before you get to lay the first brick getting planning and other approvals can set a major retailer back many millions more. So it was hardly surprising for Tesco to want to find ways to understand their customers and encourage their loyalty when so much investment was at stake.

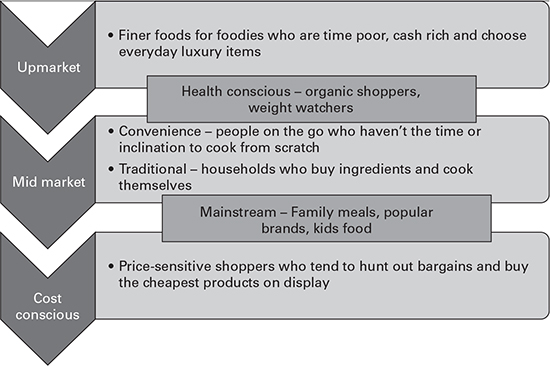

dunnhumby showed Tesco how to use Clubcard data to segment its customer base into different clusters, which became its first customer segments, giving them the catchy title of ‘Tesco Lifestyles’. This approach is a behavioural segmentation based on the concept that ‘you are what you buy.’ (See Figure 4.1)

Figure 4.1 Tesco’s Lifestyle market segments

For Tesco the real value comes in segmenting a customer base to develop tailored offers based on actual behaviour and beating competitors to the punch. After ASDA fell into Walmart’s clutches Tesco used Clubcard data to identify 300 items that price-sensitive shoppers (those that purchased mostly from the Value range) typically purchased. Working on the not unreasonable assumption that these were shoppers most likely to switch to ASDA, Tesco lowered the price of many of these items so halting customer defections.