Introduction

In December 1879 three young Native American women at the Seneca Indian School—Ida Johnson, Arizona Jackson, and Lula Walker—launched the first issue of their school newspaper, the Hallaquah.1 This was a rather extraordinary feat, considering these students were printers and editors at a time when such positions were limited for Native Americans and especially limited for young Native women. It is even more remarkable that in the inaugural issue, they proclaimed their intention to make the newspaper serve their own interests and those of the local Native American community and not strictly those of school authorities. Whereas school authorities used boarding school newspapers to promote the civilizing missions of their schools and showcase the transformation of their students, the Indian schoolgirl editors of the Hallaquah had something else in mind.2

As they announce in their first editorial: “We desire and intend that the Hallaquah shall represent the spirit of our school and always speak in behalf of its interest. Supported directly by the Hallaquah Society, it yet is intended to be a true exponent of the Seneca, Shawnee, and Wyandotte Industrial Boarding School, and a news letter to the neighboring people as well as for the pupils” (Hallaquah Editorial, December 1879, this volume). Their commitment to using the Hallaquah as a vehicle for serving their community and preserving aspects of Native American cultures reflects how students learned to use the tools of the boarding school—their proficiency in English, access to new print technologies, and exposure to the dominant discourses on racial identity—to pose challenges, albeit often subtle ones, to the assimilative policies and practices of the boarding school.3

The Hallaquah belongs to a vast newspaper archive that remains largely understudied despite the fascinating insight it offers into how Native Americans used boarding school newspapers for their own purposes: to shape representations of Indianness that circulated in U.S. print culture and to foster and maintain indigenous communities of printers, editors, writers, and readers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. With a few notable exceptions, such as Karen Kilcup’s Native American Women’s Writing, Bernd Peyer’s American Indian Nonfiction, and Robert Dale Parker’s Changing Is Not Vanishing, writings by boarding school students and prominent Native American public intellectuals that appeared in boarding school newspapers have lacked critical attention and thus remain virtually unknown and unavailable to most scholars and students of Native American literature. Recovering Native American Writings in the Boarding School Press fills this gap in the scholarship by making available a representative sampling of Native-authored letters, editorials, essays, short stories, and retold tales published in boarding school newspapers.

For Native Americans of this generation, the federal boarding school experience in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries meant many things, and yet one common thread that binds the thirty-five writers and editors in this collection together was that they employed the periodical as a powerful tool for writing against cultural erasure and for serving the interests of Native communities. Boarding school newspapers, much like the schools themselves, were complex sites of negotiation. Writing for and editing boarding school newspapers, Native Americans developed multiple strategies to negotiate the different and sometimes competing demands and expectations of Native and non-Native audiences in order to gain visibility and the authority to speak. This collection of rich and diverse writings is intended to provide readers with a greater understanding of how boarding school students and Native American public intellectuals demonstrated their agency by fashioning identities for themselves as writers and editors, thus contributing to an expanding history of Native American literature.

Recovering Native American Writings in the Boarding School Press is addressed to readers interested in Native American literature or history, late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American literature, periodical studies, and U.S. print culture. In this collection readers encounter student-authored texts in a variety of genres from personal letters and autobiographical essays to short stories. The compilation ultimately offers readers insight into the boarding school legacy and its influence on Native American literary production. Besides student writings, selections include writings by prominent Native American literary figures like Gertrude Bonnin or Zitkala-Ša (Yankton Sioux), Charles Alexander Eastman (Santee Sioux), Arthur Caswell Parker (Seneca), Angel De Cora (Winnebago), and John Milton Oskison (Cherokee), among others, who used boarding school newspapers as a forum for their writings on a range of topics. As the writings collected here reveal, Native Americans used the boarding school press for various purposes—as a vehicle for voicing the interests of their communities, for celebrating tribal identity and preserving oral traditions, and for cultivating networks of Native American editors, writers, and readers at the turn of the twentieth century.

Critical Contexts

Recovering Native American Writings in the Boarding School Press is informed by and contributes to critical conversations in Native American studies that complicate our understanding of the experiences of boarding school students and the influence of boarding schools on Native American literature. The important work of Native scholars Brenda J. Child (Ojibwe), K. Tsianina Lomawaima (Creek), and Robert Warrior (Osage) has allowed us to move beyond seeing boarding school students and prominent Native American writers affiliated with these schools—Bonnin, Eastman, De Cora, Carlos Montezuma (Yavapai), and others—as simply assimilated victims or simply resistant. Boarding school students had complex and competing responses toward their schooling. These scholars have worked to understand boarding school experiences by reclaiming the voices and writings of students and making them central to discussions of Native American literature.

Despite an interest in recovering student voices, Native and non-Native scholars have been slow to embrace boarding school newspapers in their search for Native-authored texts. One possible explanation for this is the tendency in Native American literary studies to privilege the book over other forms. Warrior’s third chapter of The People and the Word, titled “The Work of Indian Pupils: Narratives of Learning in Native American Literature,” is exemplary in this regard. Central to Warrior’s project in the chapter is the notion that Native-authored educational texts, including texts written by boarding school students, are “the backbone of Native American literature” (Warrior, People, 100). Warrior searches for student voices in boarding school newspapers like the Indian Helper, a white-edited newspaper printed by Native American male students at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, and although he briefly examines only one student-authored text, an essay by Dennison Wheelock (Oneida), he focuses most of his attention on well-known boarding school narratives that were published in book form: Zitkala-Ša’s American Indian Stories, Eastman’s From the Deep Woods to Civilization, and Luther Standing Bear’s My People the Sioux. These influential books have already garnered significant critical attention, whereas boarding school newspapers remain largely understudied.

By giving only brief consideration to one student-authored text published in a boarding school newspaper, Warrior misses an important opportunity to engage with lesser-known writers and texts that deepen our appreciation of Native educational experiences. Given the privileging of the book in Native American literary studies, it is unsurprising that Warrior’s study focuses mostly on retrospective accounts of boarding schools that were published in book form and engages only briefly with boarding school newspapers that contain educational narratives written by students while they were still at school. Scholarship in the main has ignored boarding school newspapers and Native-edited periodicals like the American Indian Magazine, the organ of the Society of American Indians (SAI), despite the recognition by a handful of literary scholars and historians that these periodicals served as important outlets for Native American literary production in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.4

Another reason why boarding school newspapers remain understudied is that scholars are skeptical of them and the Native-authored texts they contain. Child, whose groundbreaking study of unpublished student letters offers a more complicated understanding of boarding school experiences, acknowledges that boarding school newspapers “present an especially intriguing category for analysis,” but she dismisses them as simply promoting an assimilationist agenda (Child, Boarding, xvi). Child is right to point out that school authorities often exerted strict editorial control over boarding school newspapers. It is likely that even student-run newspapers like the Hallaquah were produced with oversight and possible censorship from school authorities, and thus they should be read with some degree of skepticism. I would argue, however, that all periodicals, including boarding school newspapers, are products of complex negotiations between editors, writers, and readers, and because of that they are objects worthy of study.

New scholarship asserts that boarding school newspapers are an untapped archive for scholars working to recover early indigenous writings and to challenge the restrictive assimilationist-resistance binary that has dominated narratives of the boarding school experience. Scholars who have worked on recovering student-authored texts in boarding school newspapers underscore that this newspaper archive reveals important continuities between student writers and Native American public intellectuals like Bonnin, Eastman, Montezuma, and Laura Cornelius Kellogg (Oneida), among many others.5 The present collection contributes to this recent scholarship by emphasizing that boarding school newspapers are important sites for recovering Native American print histories. In it I seek ultimately to demonstrate that Native American boarding school students and public intellectuals capitalized on the periodical’s ability to create conversations and debates among a growing network of Native American consumers and producers of print that extended beyond federal boarding schools in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The Boarding School Legacy and Early Native American Literature

The writers and editors featured in this collection belong to an emerging canon of early Native American literature that notably includes students who attended missionary-run boarding schools in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Students of this earlier generation produced a variety of writings using their English-language literacy for their own purposes, as scholars such as Joanna Brooks, Hilary Wyss, and Theresa Strouth Gaul have suggested. The early student writers and the boarding schools they attended serve as precursors to later federal boarding schools and the student writers and public intellectuals connected with them. Briefly tracing some of the similarities between the boarding schools of these two generations and the Native writers affiliated with them allows us to better appreciate the prehistory of the writings reprinted in this collection.

The federal boarding schools of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had their “roots” in the mission boarding schools located in the Northeast in the eighteenth century and in the Southeast in the early nineteenth century (Warrior, People, 106). One of the first boarding schools established to convert and educate Native Americans was Moor’s Indian Charity School, founded in Connecticut in 1754 by Eleazar Wheelock. A Congregational minister and mentor to the Mohegan writer Samson Occom, Wheelock established his school to prepare Native American missionaries to convert tribes in New England and beyond. He gave his students a college-preparatory education; however, as Brooks explains, that changed in 1762, when, facing criticism from sponsoring missionary societies, Wheelock “retooled the Moor’s curriculum to focus more on preparing his students for the practical aspects of their future duties as missionaries and schoolmasters, small farmers, and domestic servants” (Brooks, The Collected Writings, 16). Moor’s was eventually relocated to New Hampshire and reconstituted as Dartmouth College.

The next major effort to convert and educate Native Americans in boarding schools was not until 1810, with the establishment of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). The ABCFM founded the Brainerd School, which was located in what is now Tennessee and focused on Cherokee education, and the Cornwall Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, Connecticut. Although the Brainerd School and other ABCFM mission schools in the Cherokee Nation served as models for the later federal boarding schools, Gaul points out a crucial difference between them: “Cherokee leaders chose to invite the American Board missionaries into the Nation, encouraged them to open more and more schools, and enrolled their children in the schools” (Gaul, Cherokee Sister, 14). Influential Cherokee figures like Catharine Brown and Elias Boudinot attended these schools and later used their English-language literacy and their access to print culture in the service of their communities. Not only did Brown gain an audience for her writings and help shape public opinion, but as Gaul explains, her literary corpus comprises thirty-two recovered letters and a diary, making her, after Occom and John Johnson (Mohegan), “the most prolific Native writer before the late 1820s” (Cherokee Sister, 5). Boudinot founded the Cherokee Phoenix, the first tribal newspaper, in 1828 and is therefore considered an important figure in the history of the Native American press.

Early missionary-run boarding schools produced texts that represented students as passive recipients of a Native education in English literacy—what Wyss terms “Readerly Indians”—and used student writing for fundraising purposes, as would federal boarding schools in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In her study of early missionary-run boarding schools, Wyss notes how in the 1760s Wheelock sent student handwriting samples, letters, and other schoolwork to secure continued funding from benefactors in England and Boston. Wheelock also reprinted letters by pupils David Fowler (Montaukett) and Joseph Woolley (Delaware) in his 1766–67 English narratives. Both letters, Wyss points out, “are substantially longer than the version he reprints in his narratives” (Wyss, English Letters, 60). Wyss demonstrates how Wheelock exercised control over the narratives by excising details that might reflect poorly on him; for example, Wheelock leaves out Fowler’s mention of how much money he will need to live on and Woolley’s concern over the shortage of funds. Wyss’s examination of how figures like Wheelock used Native writings contextualizes our understanding of how later boarding school authorities like Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, used student-authored texts in the school newspapers they edited to create narratives of “progress” and total transformation, as I discuss later.

While Wheelock and other school authorities sought in their missionary literature to represent their students as “Readerly Indians,” Wyss argues that Native Americans demonstrated their agency by becoming what she terms “Writerly Indians.” As Wyss observes, “Writerly Indians used written discourse to manage their own sovereignty in ways that often challenged, confused, or contradicted missionary desire. At times, however, that sovereignty meshed nicely with missionary goals. Either way, the Writerly Indian figure left evidence of a powerful commitment to the continued existence of Native communities, even in the face of sometimes overwhelming rhetorical and political challenges to that identity” (Wyss, English Letters, 7).

Wyss also emphasizes not what Native Americans connected to these early missionary-run boarding schools wrote but that they wrote: “Those Natives who did write, no matter what they wrote, fundamentally altered the relationship between missionary culture and Native people through the simple act of self-expression” (7). By suggesting that the act of writing itself should be understood as a demonstration of agency and an effort to control their own representation, Wyss models a way to move beyond the critical tendency to see early boarding school students and their later counterparts who attended federal boarding schools as passive recipients of an assimilative education.6

Wyss’s concept of the Writerly Indian provides a useful framework for understanding how the boarding school students and prominent Native American public intellectuals featured in this collection used their English-language literacy in ways that at times may have supported the assimilationist goals of the boarding schools and that were at other times unanticipated by school authorities and at odds with the schools’ civilizing missions. The Hallaquah and other boarding school newspapers thus reflect the complexities of Native writers’ positions and contain a range of perspectives—sometimes, within the same issue, writings by Native Americans who assert their tribal identities in an effort to preserve them against the school’s programs of cultural erasure appear alongside Native-authored texts that promote the school’s assimilationist agendas.

Native American Periodical Networks

Periodicals served as important publication venues for early Native American writers. The Native American press is considered to have begun with the launch of either Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s Muzzinyegun in 1826 or Elias Boudinot’s Cherokee Phoenix in 1828. Native American press historians Daniel F. Littlefield Jr. and James W. Parins consider the Muzzinyegun the first Native American periodical because Schoolcraft’s Ojibwa wife, Jane, and her mother and brother contributed much of the content to the newspaper. Jane wrote poetry as well as articles on Ojibwa folklore and history (Littlefield and Parins, American Indian, xii, xx). The same year Schoolcraft’s periodical was founded, Boudinot, while on a speaking tour, expressed the need for a tribal newspaper. The American Board of Foreign Missions helped him raise funds to purchase the press and equipment. The Cherokee Phoenix was published in English and Cherokee and was established, as Littlefield and Parins explain, “as a direct response to Georgia’s efforts to extend her laws over the Cherokee Nation” (American Indian, xii). The Phoenix published local news, educational essays, poetry, and letters.

Other noteworthy periodicals edited by Native Americans include the Cherokee Rose Buds published at the Cherokee Female Seminary in Oklahoma in 1854, Carlos Montezuma’s pamphlet Wassaja, and the pan-tribal Quarterly Journal of the Society of American Indians. Catharine Gunter and Nancy E. Hicks, who edited the Cherokee Rose Buds, are two of the earliest known young Native American women to assume the role of editor of their school newspaper. The Cherokee Rose Buds was a three-column newspaper of eight pages that contained original poetry, essays, and narratives composed by students. As Littlefield and Parins note, this was not an ordinary school newsletter but a vehicle “for the literary expression of the students, who were exposed to a classical education” (American Indian, xx, 407). Montezuma’s Wassaja was published in Chicago from 1916 to 1922. According to Rochelle Rainieri Zuck, the pamphlet reflected Montezuma’s view that “the American Indian press should communicate the material realities of American Indians and focus on the development of strategies and tactics to fight the BIA [Bureau of Indian Affairs]” (Zuck, “‘Yours,’” 79). The influential Quarterly Journal of the Society of American Indians (later renamed the American Indian Magazine) was launched in 1913. Arthur C. Parker served as editor-general until Gertrude Bonnin assumed the editorship in 1918.7

As publishing opportunities for Native Americans began to expand in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, prominent figures like Bonnin, De Cora, and Eastman found outlets for their short stories and autobiographical essays in magazines with a predominantly non-Native readership like the Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s Monthly, and St. Nicholas: An Illustrated Magazine for Young Folks. These early Native American writers were boarding school graduates with connections to Carlisle. Indeed, it was partially through their affiliation with Carlisle and its periodical networks that they learned how periodicals could serve as a powerful tool for shaping public perceptions of Native Americans. They used their periodical writings, in the words of A. Lavonne Brown Ruoff, to educate “white audiences about the intellectual and creative abilities of Indian people, the value of their tribal cultures, and white injustice to Native peoples” (Ruoff, Foreword, x).

At the same time, they sought to reach a broader audience that included Native American readers in their efforts to cultivate and sustain pan-tribal networks of communication. In this way they resembled their eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century precursors who established northeastern networks by adapting print and English-language literacy practices to serve as tools for resistance and change, as the work of Lisa Brooks (Abenaki), Matt Cohen, and Phillip H. Round demonstrates.8 Bonnin, De Cora, Eastman, boarding school students, and other writers of their generation recognized early on that boarding school newspapers and Native-edited periodicals provided the best venues for reaching a mixed audience of Native and non-Native readers. That is why, according to Bernd Peyer, boarding school newspapers and Native-edited periodicals like the Quarterly Journal of the Society of American Indians constitute a major archive for nonfiction prose as well as fiction and poetry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Peyer, American Indian Nonfiction, 26). Native Americans used these periodicals as outlets not only for self-expression but also for community building. Student editors of the Seneca Indian School’s Hallaquah, Hampton Institute’s Talks and Thoughts of the Hampton Indian Students, and the Carlisle Indian Industrial School’s School News as well as editors of the Quarterly Journal employed reprinting, a common journalistic practice at the turn of the twentieth century, in their efforts to strengthen communication between disparate networks of Native American editors, writers, and readers. They also announced and supported other periodicals edited by or written for Native Americans. The editors of the Quarterly Journal even published several pieces on boarding school newspapers.

For example, in the “Editorial Comment” in the January–March 1915 issue Arthur C. Parker notes that in every boarding school newspaper he has examined “there is an expressed spirit of cheer and of helpfulness.” Parker goes on to emphasize the value of boarding school newspapers and their mission. That mission, as he explains, is not only to give students who want to learn instruction in printing but also to keep students, parents, and the public informed of the educational work of the school. Parker further asserts, “All of these purposes are worthy ones, and the school paper deserves the support of the field it reaches and the appreciation of the public” (“Editorial Comment,” 5–6). Parker’s editorial ultimately reveals his belief that boarding school newspapers and the Quarterly Journal served as tools for fostering and sustaining pan-tribal networks of periodical producers and consumers.9

Native American editors and writers also used boarding school newspapers to debate pressing issues that were important to the survival of Native American communities in the face of the assimilationist imperative of the boarding school and the dominant culture more broadly. This newspaper archive thus troubles the assumption that Native Americans voiced static or homogenous perspectives on issues like assimilation, citizenship, and education; indeed, these issues were widely debated in Native writings that appeared in boarding school newspapers. It is because boarding school newspapers offer disparate and often competing perspectives that they provide a richer sense of the conversations and debates that transpired between and among boarding school students and prominent Native American public intellectuals at the turn of the twentieth century.

Given the complicated institutional contexts of the production of boarding school newspapers, it should come as no surprise that the writers and editors featured in this collection engaged in the assimilationist and progressivist rhetoric of their day in complex and sometimes contradictory ways. Although many of them voiced critical perspectives that posed challenges to the assimilative thrust of federal boarding schools and the dominant culture more broadly, most of the time their resistance was subtle. As Gale P. Coskan-Johnson explains in her insightful literary recovery of Charles Eastman, “Revolution is only occasionally ‘blood in the streets’; what we are more likely to find here, given the overwhelming hegemony of American cultural and military forces in the United States at the time, is something trickier, more sophisticated, and heavily veiled—something that would protect the speaker from retribution and so allow her or him to continue speaking” (Coskan-Johnson, “What Writer,” 111).

Boarding school students, who lacked the relative cultural authority of prominent Native American public intellectuals like Eastman, had to develop even trickier and subtler strategies in their writings in order to express their critical perspectives and their commitment to Native communities and to change. In a more telling example, even a writer like Bonnin, whom Dexter Fisher described as “the darling” of the northeastern literary establishment, found herself engaging in pen wars with school authorities who sought to silence and discredit her in print (Fisher, “Zitkala-Ša,” 229). The editorial comments accompanying Bonnin’s essays reprinted in this collection serve as a reminder of the obstacles she and other Native Americans were up against in the contest over representations of Indian identity in the boarding school press and the complex rhetorical strategies they used in their writings in order for their voices to be heard. Like Eastman, who, as Coskan-Johnson writes, “engaged in a rich Native American public discourse that circulated in and out of national discussions of identity and politics,” so too did Bonnin, boarding school students, and other writers of this generation (Coskan-Johnson, “What Writer,” 130).

The Boarding School in Context

With a few notable exceptions, like the Hallaquah, which was published at a reservation boarding school, most of the writings in this collection were first printed in newspapers published at off-reservation boarding schools. Missionaries assumed the primary responsibility for educating Indian children until the 1870s when the federal government took direct control over Indian education, and policy makers began to shift away from day and reservation schools in favor of off-reservation boarding schools. This shift can be explained in part by a change in public attitudes toward Native Americans, especially among eastern reformers, who saw education as the solution to what had long been deemed the “Indian problem.” Samuel Chapman Armstrong and Richard Henry Pratt were among a cohort of reformers known as the “friends of the Indians” who believed strongly in Indians’ ability to be educated in preparation for citizenship.10 Both Armstrong and Pratt set out to prove that Indians were educable by establishing the first federal off-reservation educational programs designed to eradicate “from students every available trace of Native identity and replac[e] it with a facsimile of whiteness” (Warrior, People, 112).

The genesis of the federal government’s system of off-reservation boarding schools for Native Americans was Pratt’s educational venture at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida.11 Pratt’s program for Indian prisoners at Fort Marion sought to prove that Native Americans could be educated and civilized. He taught the prisoners English and aimed to instill in them habits of discipline, work, and cleanliness. The containment and seclusion of the fort provided what Pratt believed were ideal conditions for civilizing Native Americans; he would later recreate this model at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania (Fear-Segal, White Man’s Club, 15–18).

Pratt’s experiment with the prisoners at Fort Marion set a precedent for the creation of the first formal federal off-reservation educational program for Indians. In 1878 Samuel Chapman Armstrong opened the doors of Hampton Institute in Virginia, founded in 1868 to provide freed slaves with a vocational education, to some of the recently released Fort Marion prisoners.12 One year later Pratt founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which became the prototype for federal off-reservation boarding schools across the United States.

The aim of federal boarding schools like Hampton and Carlisle was the same: to provide Native American students with the teachings of civilization in the form of a practical, vocational education. In keeping with the civilizing mission of these schools, students were first taught how to speak, read, and write in English.13 The government established an English-only policy in boarding schools that reflected a belief in the superiority of English over Indian languages. The imposition of an English-only education was highly politicized: the policy, which was strictly enforced from the 1880s until the 1930s, solidified the notion that the acquisition of English was the primary purpose of education for Native Americans.

As soon as students understood English they were to begin studying other academic subjects like math, geography, and U.S. history. Students received a “half and half” education, meaning that their academic education was accompanied by vocational training designed to enable them to become self-sufficient workers. Students spent part of the day learning trades or performing manual labor and a few hours each day in the classroom. Girls received a domestic education to prepare them to become wives and maids. Boys learned how to use tools and acquired skills associated with farming, blacksmithing, and carpentry. Some male students received training in printing and worked in the printing offices.

From the beginning of their educational experiments, Armstrong and Pratt set out to sway skeptics about the educability of Indians. As Pratt once explained, his was a twofold educational program: “We have two objects in view in starting the Carlisle School—one is to educate the Indians—the other is to educate the people of the country . . . to understand that the Indians can be educated” (“Indian School Commencement,” Sentinel, 2). Both Hampton and Carlisle established printing offices to aid in their attempts to demonstrate that Indians were educable. Male students were responsible for printing all the publications produced at the printing offices at Hampton and Carlisle. Carlisle’s weekly Indian Helper advertised this fact, announcing on the front page of every issue that it was “printed by Indian boys.” The newspapers themselves attempted to prove to a skeptical public that by providing training in printing to Indian students, the boarding schools were offering them a means of attaining economic self-sufficiency.14

In addition to showcasing the printing skills of their students in the various school publications, Armstrong, Pratt, and other school authorities frequently published student writings in the pages of the school newspapers to demonstrate to white readers that students were successfully learning the language of civilization. Alongside the student writings and writings about fully assimilated Indians, they printed before-and-after photographs capturing the cultural transformation students underwent at the schools. Together, the photographs and writings told a narrative of assimilation designed to convince white readers that Hampton’s and Carlisle’s educational programs could not only transform “savages” into students but could do so quickly. In this way the white-edited newspapers played a crucial role in gaining the financial and political support of white readers. Armstrong and Pratt sent copies of their newspapers to “every member of Congress, all the Indian agencies and military posts, and the most prominent American newspapers” (Enoch, “Resisting,” 122). For Armstrong, Pratt, and other school authorities, the boarding school press was an important medium for gaining the support of whites in order to ensure the success of their educational experiments.

Armstrong and Pratt relied heavily on the periodical press to gain public approval of and financial support for their educational programs, especially among those who might influence the government’s policies on Indian education. The white-edited school newspapers served as an important link between school authorities and Washington and helped shape government Indian policy from the late nineteenth century through the early decades of the twentieth (Littlefield and Parins, American Indian, xxviii). They also provided a means for Armstrong, Pratt, and other school authorities to respond to critics of Indian education.

As early as the 1880s critics began to voice concerns over the system of education practiced at off-reservation boarding schools. According to historian Robert A. Trennert, after 1900 “critics became more vocal and persistent, arguing that the Indian community did not approve of this type of education, that most students gained little, and that employment opportunities were limited at best” (Trennert, “Educating,” 288). Commissioner of Indian Affairs Francis E. Leupp (1905–1909) argued that the educational system not only failed to produce self-reliant Indians and to provide students with a useful education but also protected them in an artificial environment in boarding schools, where they received the comforts of civilization at no cost and without developing a work ethic.

In order to demonstrate that their educational programs could Americanize Indian students, school authorities printed representations of students in the pages of their newspapers that showcased their “progress.” Coverage of Indian Citizenship Day pageants, sporting events, and graduations was meant to signal to white readers that students were capable of being transformed.

Besides playing a role in promoting the educational work of the schools, the white-edited newspapers at Hampton, Carlisle, and other boarding schools performed specific roles for their Native American readers. These newspapers functioned first and foremost as a pedagogical tool for boarding school students and graduates. As Jessica Enoch points out, Carlisle’s white-edited Indian Helper “taught current and former Carlisle students the rules of etiquette, English, and white behavior, reinforcing the pedagogical objectives learned in the classroom” (Enoch, “Resisting,” 122). Hampton’s white-edited Southern Workman also performed a pedagogical role for students: not only was the Workman the main text in all the reading courses offered at Hampton, but like the Indian Helper, it printed success stories of model students and graduates for other students to emulate (Anderson, Education of Blacks, 50). Furthermore, the white-edited newspapers printed at Hampton and Carlisle served as a disciplinary and surveillance device designed to keep student readers in their place.

Boarding school newspapers, much like the schools themselves, were complex sites of negotiation. Whereas school authorities used the white-edited school newspapers to publicize their efforts to erase their students’ Indianness by imprinting them with the markers of a white middle-class cultural identity, students often used the school newspapers to defend and preserve Native American identity and culture against the assimilationist imperatives of the boarding schools and the dominant culture. Writing for, editing, and printing school newspapers, students learned how to negotiate the demands placed on them by school authorities who oversaw these publications.

Writers and Themes

Of the thirty-five writers and editors whom I have selected to include in this collection, some may be unfamiliar to readers. The students I have selected are notable because they contributed regularly to their school newspaper and some of them even served as editors. Although many of the students who contributed to boarding school newspapers did not continue to publish after they graduated, there are a few exceptions. Hampton Institute graduate Harry Hand (Crow Creek Sioux) founded his own tribal newspapers, the Crow Creek Herald and the Crow Creek Chief. Hand died only one year after he founded the Chief; however, his ambition to serve his community by starting his own newspapers speaks volumes about his belief in the power of the periodical press. Elizabeth Bender (White Earth Chippewa), also a Hampton graduate, continued to publish nonfiction prose in the boarding school press. Through her active membership in the SAI, Bender met and married Henry Roe Cloud (Winnebago), a founding member of the organization. Roe Cloud founded the American Indian Institute, where Bender taught as well as contributed to the institute’s newspaper, the Indian Outlook. Other more prominent writers like Charles Eastman (Santee Sioux) and Angel De Cora (Winnebago), who were boarding school graduates and active members of the SAI, may be familiar to readers, yet many of the writings they published in boarding school newspapers have never before been published in a collection. Recovering Native American Writings in the Boarding School Press provides readers with a greater understanding of how these writers engaged each other about a range of topics from education and citizenship to tribal art.

A crucial topic for many writers collected here is education, and a number of them set out to reflect on the boarding school experience. Boarding school students and graduates responded in multiple ways to their schooling; some took a rather positive view of it, as we see in writings by Henry C. Roman Nose (Southern Cheyenne), Mary North (Arapaho), Luther Standing Bear (Pine Ridge Sioux), and Samuel Townsend (Pawnee), all of whom contributed to the School News. Although the School News was edited by Townsend and another Carlisle student, Charles Kihega (Iowa), it is likely that the newspaper’s content was closely monitored by Pratt and Marianna Burgess, who supervised the printing office. This may explain why, in their writings, students seem to reflect the views of school authorities and are less critical of their boarding school experience, which was, in the words of historian David Wallace Adams, an “education for extinction.”

Roman Nose’s autobiographical essays appeared in the School News from June 1880 through March 1881. He was one of the Fort Marion prisoners who accompanied Pratt to Hampton and then to Carlisle, where he stayed two years to learn the tinning trade. In his autobiographical essays Roman Nose chronicles his journey from Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, to Carlisle. He also charts his progress from his Indian boyhood marked by hunting and battles to his success as a Carlisle student, which he attributes to his learning English: “They stayed in prison there three years and we had no school, but Capt. Pratt showed us ABC and now we understand these letters. We did not know how to spell anything . . . but [we]have certainly been much benefited” (Roman Nose, “Experiences 1880,” this volume).

Like Roman Nose, North and Standing Bear emphasize the benefits of their schooling. North contrasts her life as a Carlisle student with her life on the reservation: “When we were at home in Indian Territory we had nothing to do but play and go to the river and go in swimming and now we are way off from home at school and learning something” (North, “A Little Story,” this volume). She tells us that what she is learning is how to write a story, which will give her practice expressing herself in English. In contrast to North, Standing Bear reveals in a letter to his father some of his struggles to learn English: “We are trying to speak only English nothing talk Sioux. . . . I have tried. But I could not do it at first. But I tried hard every day. So now I have found out how to speak only English. I have been speaking only English about 14 weeks now I have not said any Indian words at all” (Standing Bear, Letter to Father, this volume).15

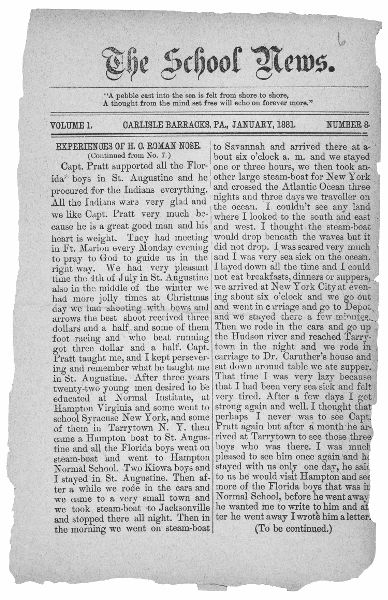

Fig. 2. Front page of the School News, January 1881. General Research Division, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

The writings of Roman Nose, North, and Standing Bear bring into focus how students negotiated an English-only policy designed to result in their loss of their respective first languages. These students, like so many educated at Carlisle and other boarding schools, were subject to a strict English-only policy that prohibited them from speaking Indian languages on school grounds. Their writings reveal that they did not overtly challenge the English-only policy but rather believed that English-language literacy offered them, their fellow classmates, and even their elders an opportunity for social and economic gain (Standing Bear urges his father to learn English). This was the same message Pratt espoused in his efforts to convince Native American parents to send their children to his school: “Cannot you see it is far, far better for you to have your children educated and trained as our children are so that they can speak the English language, write letters, and do the things which bring to the white man such prosperity, and each of them be able to stand for their rights as the white man stands for his?” (Pratt, Battlefield, 223). Pratt underscored the link between literacy, advancement, and citizenship. He and other school authorities wedded their belief in the promise of literacy to the ideology of social evolutionism. As Amelia Katanski explains, they believed that literacy would “transform students as they ‘progressed’ from tribal ‘savagery’ to Western ‘civilization’” (Katanski, Learning to Write “Indian,” 4). At the same time they considered literacy not only a marker of civilization but also an indicator of students’ complete transformation or loss of Indianness (Katanski, Learning to Write “Indian,” 131).

What Pratt and other school authorities failed to understand, however, was that most students were not simply going to give up their first languages and Native identities and sever their ties to their tribal communities once they acquired English-language literacy. For many students learning English did not result in a total transformation. Rather, those who learned English and became proficient in it gained the power to use it to serve their communities. In this way they resembled prominent boarding school graduates like Bonnin and Eastman, who as Warrior explains, “wanted what the schools they attended offered. Yet they also wanted to have a stake in their own destiny” (Warrior, People, 116). By fashioning identities for themselves as writers in the pages of boarding school newspapers, students gained control over their self-representations and revised what it meant to be educated Indians, just as Samuel Townsend did in his editorials in the School News.

In his July 1880 editorial Townsend challenges white stereotypes about Native Americans as uneducable and uncivilized:

Some white folks say that the Indians do not know anything and can’t learn anything, but the Indians are learning something. Great many of the white folks never read about the Indians and they do not know anything about us, but sometimes they talk bad about us and they say that the Indians have no brains to think with and they can’t learn anything. Sometimes they say Indians can not be civilized. Maybe those white folks don’t know anything. (Townsend, Editorial, July 1880, this volume)

Here Townsend argues that Native American students were learning and gaining much from their education. He also reverses what white critics say about the ignorance of Native Americans: he argues that those critics are ignorant about Indians’ ability to earn an education and integrate into the dominant culture on an equal basis. In the same editorial Townsend uses cross-cultural comparisons to stress that like whites, Native Americans “can do most anything” so long as they are given an education.

Furthermore, he argues, Native Americans are not to blame for the slow spread of civilization. He insists instead that the blame rests with the lack of federal funding for boarding schools: “If every Indian boy and girl were in school it would not take long to civilize all the Indians. The reason it takes so long is because Washington does not give enough money to put all the Indian children in school.” Admittedly, Townsend’s rhetoric echoes some of Pratt’s thinking about the fundamental role of education in civilizing Native Americans. However, more significantly, Townsend’s editorial demonstrates that he is not a passive recipient of his boarding school education; indeed, he uses the School News as a venue for “talking back,” to borrow a phrase from historian Frederick E. Hoxie. By talking back to members of the dominant culture, Hoxie writes, “Natives made it clear that they refused to accept the definitions others had of them—savage, backward, doomed” (Hoxie, Talking Back, viii). For Townsend, “talking back” meant challenging, albeit in subtle ways, white stereotypes of Indians and the assumption that white culture was superior.

Writing more than thirty years later, long after Pratt was forced to resign from Carlisle in the wake of increasing criticism of his approach to Indian education, John Milton Oskison (Cherokee) praised Carlisle and other boarding schools for what they were doing for Indians.16 In “The Indian in the Professions” Oskison challenges the notion that Carlisle graduates return to the blanket by offering examples of how educated Indians have entered a number of professions, including “teaching, nursing, the law, the diplomatic service, the ministry, medicine, politics, dentistry, veterinary surgery, writing, painting, acting.” Furthermore, he writes, “The professions are wide open to us. We have the strength and the steadiness of will to make good in them” (Oskison, “The Indian in the Professions,” this volume). For Oskison and others, an education at Carlisle, and better yet, a degree from a college or university, “could be a means to do what he and the SAI urged the Indians to do: take their future into their hands and speak for themselves as Indian individuals and Indian peoples” (Larré, “John Milton Oskison,” 11).

Several writers in this collection argued for higher education for Native Americans. For example, in an address Charles Eastman delivered at a Carlisle commencement and which appeared in the February–March 1899 issue of the Red Man, he narrates the story of how he became an educated Indian.17 Eastman, who graduated from Dartmouth and earned his medical degree at Boston University, writes, “[S]ome twenty-five years ago, I took my blanket and my bag and started from Sioux Falls, in South Dakota, to the Santee Agency up above Yankton on the Missouri River, some one hundred and thirty miles, on foot in search of education” (Eastman, “Address at Carlisle Commencement,” this volume). Although it begins with his account of schooling, Eastman’s address is not merely an account of his success as a model boarding school graduate. Rather, Eastman uses his audience’s interest in him as an educated Indian for his own purposes. Unlike Pratt and other school authorities who opposed higher education for Native Americans and imagined a future in which they were absorbed into white culture as landholders and farmers, Eastman articulates an alternative vision. He envisions a future in which educated Indian leaders with “purer and higher ideals” would “press steadily onward and upward, that we [Indians] may some day take a distinctive part in the great civilization of this western nation.” Echoing the rhetoric of uplift commonly associated with African American public intellectuals like W.E.B. Du Bois, Eastman reveals that he believed strongly that a higher education would prepare Native Americans for their future roles as leaders of the race.

Also believing in the advantages of higher education, Arthur C. Parker (Seneca) argues for an Indian college or university. In his essay “Progress for the Indian” Parker writes, “The great need of teaching the Indian to appreciate and measure his own culture in the full knowledge of others is apparent. To this end the writer strongly believes in the necessity of an Indian college or university. In such an institution graduates of the higher schools might be trained in the art, literature, history, ethnology, and philosophy of their people” (Parker, “Progress for the Indian,” this volume). In their periodical writings, Oskison, Eastman, and Parker, among others emphasized the importance of higher education to an indigenous future.

For most of the writers in this collection, being an educated Indian meant challenging the notion of the vanishing Indian with their own counter-representations of Indians as capable of change. Elizabeth Bender represents her people in a moment of transition in “The Land of Hiawatha,” an essay that appeared in the June 1907 issue of the student-edited Talks and Thoughts of the Hampton Indian Students.18 She subtly disrupts the discourse of the vanishing Indian celebrated in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “The Song of Hiawatha” by representing the Chippewas not as disappearing culturally but rather as capable of change. Her negotiation between a desire to preserve Ojibwa traditions and an embrace of cultural change becomes more complex toward the end of the essay as she mentions the inevitable passing of “old ways,” meaning hunting and gathering, and praises “civilization, with cozy homes and well kept farms” (Bender, “Land of Hiawatha,” 4). Bender embraces the transformation of a hunter-gather culture to an agricultural one and speaks positively of her tribe’s transition to farming: “Most of the Chippewas are engaged in farming, and are quite industrious. The reservation life has somewhat retarded their progress, but in spite of obstacles and hardships they are making a brave struggle” (Bender, “Land of Hiawatha,” 4). By emphasizing that Indians could change and were changing, Bender challenges the myth of the vanishing Indian, while at the same time she insists that Chippewas are retaining their cultural ties.19

Other writers featured here also challenge representations of Indian cultures as vanishing by showcasing how indigenous traditions like storytelling, dancing, and art remain important to Native communities. Students like Harry Hand, Joseph Du Bray (Yankton Sioux), and Anna Bender (White Earth Chippewa) transcribed oral traditions into English and then preserved them in print in Talks and Thoughts. Hand’s illustrations also accompanied some of his writings. The students’ retold tales often depict how stories are passed down from a revered storyteller to the younger generation. By retelling oral traditions in boarding school newspapers, these writers contribute to the efforts of more well-known writers like Francis La Flesche (Omaha) and Gertrude Bonnin (Yankton Sioux), who sought to preserve oral traditions for future generations of Native Americans while educating white readers about the value of their tribal cultures.20

Bonnin often portrayed Native traditions positively in her periodical writings. For example, in her 1902 article “A Protest Against the Abolition of the Indian Dance” she likens Native American culture to a frozen river waiting to “rush forth from its icy bondage” (Bonnin, “Protest,” this volume). Meanwhile, white assimilationists hack away at the ice, hissing “immodest” and “this dance of the Indian is a relic of barbarism.” Bonnin rails against the notion that the Indian dance is “barbaric.” Turning a critical gaze upon the dominant culture, she challenges white readers to see their assumptions and values reflected through the eyes of an educated Native American woman writer. She suggests that “the yellow-haired and blue-eyed races” who wear corsets in their evening gowns as they dance to orchestral music may in fact be “barbaric.” She then writes, “In truth, I would not like to say any graceful movement of the human figure in rhythm to music was ever barbaric.” In this way, Bonnin seeks to humanize Indian dancers in the minds of her white readers. At the same time, she argues against efforts among assimilationists to destroy Native cultural traditions by abolishing the Indian dance. She suggests that the Indian dance still has value in tribal culture, especially among the older generation.

Fig. 3. Harry Hand’s illustration on the front page of Talks and Thoughts, March 1893. General Research Division, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Like Bonnin, Eastman and Angel De Cora argue for the importance of Native cultural traditions in their respective writings published in the Red Man.21 For example, in his essay “‘My People’: The Indians’ Contribution to the Art of America,” Eastman comments on the study of Native arts and crafts in boarding schools. He explains that without this instruction, most students would “grow up in ignorance of their natural heritage, in legend, music, and art forms as well as practical handicrafts” (Eastman, “‘My People,’” this volume). He goes on to praise the work of De Cora and her husband, William Deitz (Sioux), at Carlisle for attempting “to discover latent artistic gifts among the Indian students, in order that they may be fully trained and utilized in the direction of pure or applied art.” Reminding readers that “as recently as twenty years ago, all native art was severely discountenanced and discouraged, if not actually forbidden in Government schools and often by missionaries as well,” Eastman writes, “the present awakening is matter for mutual congratulations.” Eastman’s assertion that Native artists have a distinctive tradition challenges the very notion of the Indian as “primitive” and thus doomed to extinction. Likewise, De Cora writes about her art students at Carlisle: “There is no doubt that the young Indian has a talent for the pictorial art, and the Indian’s artistic conception is well worth recognition, and the school-trained Indians of Carlisle are developing it into possible use that it may become his contribution to American Art” (De Cora, “An Autobiography,” this volume). By publishing in a boarding school newspaper devoted to the continuation of Native artistic traditions, Eastman and De Cora joined other Native writers who celebrated the intellectual and artistic achievements and contributions of Native Americans to American culture.

Note on Structure and Procedures

This collection is divided into two parts: the first features writings by boarding school students; the second consists of writings by prominent Native American public intellectuals, many of whom were boarding school graduates and members of the SAI. Part 1 is subdivided into letters, editorials, essays, and short stories and retold tales to highlight the variety of genres students used to offer their unique perspectives and express their commitment to their Native communities.

The writers in this collection are arranged in chronological order, according to when their writings appeared in the boarding school press. I include their tribal affiliation and a brief profile indicating where they went to school and what they did after they graduated. Some of this information I gleaned from accounts of students and prominent figures in boarding school and other newspapers. I also relied on excellent resources like A Biobibliography of Native American Writers, 1772–1924, by Daniel F. Littlefield Jr. and James W. Parins, and Bernd Peyer’s American Indian Nonfiction. Entries that contain little information suggest that little is known about the writers.

I mined roughly fifteen boarding school newspapers for this collection, but I did not use all of them. Accessing some of these newspaper archives proved difficult if not impossible. The Peace Pipe, a biweekly newspaper published at the Pipestone Indian School in Minnesota from 1912 to 1916 is a case in point. The only existing copy of the newspaper I know of, which has been indexed and is held at the Minnesota Historical Society, is the April 1916 issue. Although the newspaper regularly published student writings, the ones that appear in the April 1916 issue are short, one- to two-paragraph compositions students wrote for their classes. I also ruled out other school papers because, like the April 1916 issue of the Peace Pipe, they do not contain substantive writings by students. In selecting student writings for this collection, I typically included ones that were of substantial length.

I chose to focus on the following boarding school newspapers because they contain writings by students and prominent Native Americans that offer insight into their perspectives:

Carlisle Indian Industrial School Publications

Carlisle Arrow. Published weekly. 1908–1917.

Eadle Keahtah Toh. Published monthly. 1880–1882.

Indian Helper. Published weekly. 1885–1900.

Indian Craftsman. Published monthly. 1909–1910.

Morning Star. Published monthly. 1882–1887.

Red Man. Published monthly. 1888–1900, 1910–1917.

Red Man and Helper. Published weekly. 1900–1904.

School News. Published monthly. 1880–1883.

Chilocco Indian Industrial and Agricultural School Publication

Indian School Journal. Published monthly. 1900–1980.

Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute Publications

Southern Workman. Published monthly. 1872–1939.

Talks and Thoughts of the Hampton Indian Students. Published monthly. 1886–1907.

Santee Normal Training School Publications

Word Carrier. Published monthly. 1884–1903.

Word Carrier of Santee Normal Training School. Published monthly. 1903–1936.

Seneca Indian School Publication

Hallaquah. Published intermittently. 1879–1881.

In terms of editing the texts reprinted here, I have maintained the original spelling and punctuation except for obvious typographical errors. I have also made minor edits to the student-authored texts for readability, using brackets to indicate alterations to the original text.

I see this book as a contribution to recent efforts among scholars to preserve and analyze indigenous archives. Many of the boarding school newspapers remain inaccessible to scholars and students. Some of these periodicals have disappeared entirely and are no longer available. Those that do still remain in hard copy are often in poor condition and in desperate need of being preserved. By publishing them in this collection, I have sought to preserve them. It is my hope that bringing visibility to these archives will spur increased efforts at preservation, especially through digitization, as well as encourage further scholarly investigation into early Native American literary production in the boarding school press and other newspaper archives.

I also see this book as an opportunity to transform the way Native American literature is taught in the college classroom. I hope this collection will encourage students to engage in more meaningful discussions about the boarding school experience and its impact on the history of Native American literature. When used in the classroom alongside boarding school narratives by prominent turn-of-the-twentieth-century writers like Bonnin, Eastman, and Standing Bear, as well as twenty-first century works like Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (2007), this collection will reveal interesting parallels and points of contrast that will help students gain a deeper appreciation of how the boarding school legacy has shaped and continues to shape Native American literature.