Smallest to largest — clay, silt, fine sand, coarse sand. The largest particle in reality is  in diameter.

in diameter.

GETTING THE SOIL RIGHT |

4 |

SOIL IS A LOT MORE THAN SAND and some leaf litter. It is a complex mixture of physical, chemical and biological components, in various combinations of these to create a wide range of different soils.

While it generally contains three different-sized particles (sand, silt and clay), the amounts of organic matter, water and soil organisms also vary, and all of these can be manipulated to produce a custom-made soil.

Plants typically grow in soil. Every soil type from sand to clay has some plants that can grow in it, but we tend to grow our edible crops in a mixture of soil particles we call loam. Loam is that mixture of clay, silt and sand that seems to have the best properties for growing vegetables — enough clay to hold water, enough sand to prevent waterlogging and enough spaces for air. Add some organic matter (up to 5% is adequate) and you have the perfect soil for growing food.

Loam contains about 40% sand, 40% silt and 20% clay, and on a small scale in a backyard garden bed these ratios can be changed. We can easily change soil by adding bentonite (clay) to sand, compost to nutrient-deficient soils and gypsum to break up some types of clay.

Nutrient levels in soils change all the time. It is the nature of plants that they decrease soil fertility, so we need to develop and use strategies to replace lost nutrients and fertility.

This is why many farmers use the “ley” system of resting a paddock and sowing it with clovers or other legumes, which repair and build soil again ready for the cereal crop next season.

Smallest to largest — clay, silt, fine sand, coarse sand. The largest particle in reality is  in diameter.

in diameter.

This is why backyard gardeners must add compost, manures and other amendments to rebuild the soil ready for next season’s food crop, and why it is important to also rotate crops so that different types of plants can re-aerate the soil and re-introduce organic matter to build healthy soil once again. As nutrients get removed by the plants we harvest, they must be replaced.

Let’s examine some of the armory you can have to create living soil, which, in turn, will create healthy food and ultimately healthy people. Soil health and soil quality are the keys to sustainable agriculture.

The best compost is made when it is a “batch” process. This means that the materials are assembled and the compost pile activated. With proper preparation, piles can be made to heat and decompose without the need for bins. This is different from what most people do — they start a small pile, typically in a commercially made plastic bin, and periodically add to it. The pile never gets large enough or hot enough to break everything down.

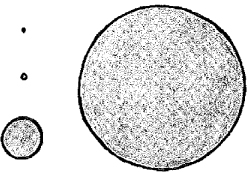

A compost bin with removable sides is the best option. Each side should be about 3 ft to 4 ft wide and high. This allows you to access the compost from more than one direction, and permits easier shifting from one bin to another. This saves using the pitchfork to lift the compost high over a bin side.

When choosing a bin, always remember that good air flow and the size of the bin, not what it is made from, determines compost production. The more open the bin, the more air can enter the pile. Avoid using the wall of a building or a fence structure as part of the compost bin or pile. Active composting will decompose walls, timber and paint.

A rotating barrel is another option, but these are limited as they generally only hold a small amount, and larger barrels are just too heavy to turn.

Composting can follow one of two pathways: cold composting and hot composting.

Some people prefer to exert themselves less and let time, nature (and earthworms) do most of the work. Cold composting is a more passive, gentle approach.

The volume is not critical, as the pile never heats up. So you can have a series of bins, and when one bin is full, starting filling the next. A technique that is adopted by many organic growers is sheet mulching, and this is essentially a cold compost made in situ. Organic garden material is broken down in the bed itself, rather than accumulating and transporting the materials to a dedicated compost bin or pile.

The cold compost pile can have problems, and may attract animal and insect pests, including mice, snails and wood lice.

One smaller-scale cold compost strategy is the bokashi method. Here your kitchen food scraps are placed in a bin and a small amount of granules, inoculated with microbes, is added. The mixture is compressed and the bin sealed with a lid, making the process anaerobic. It is more akin to fermentation where foods are “pickled”. Using fermentation to make fertilizers is discussed later in this chapter and to make or preserve foods is discussed in more detail in chapter 14.

This is by far the best method, but it does have its secrets. You need to follow the six Ms: Materials, Moisture, Mixing, Microorganisms, Minerals and Mass.

For best results, a compost pile must be, as the word implies, a composite of different materials — a mixture of plant and animal material.

To make everything work properly you need a balance of carbon and nitrogen substances. Carbon substances are “brown”, and these include plant materials and sawdust, straw, paper, cardboard and dried leaves.

Nitrogen substances are “green” and contain protein substances, so again living plants and weeds, but also animal manures and food scraps.

The ideal carbon to nitrogen (C:N) ratio is 30:1, where decomposition organisms require the carbohydrates and carbon substances to be balanced by a suitable proportion of protein or nitrogen.

Most deciduous leaves have a C:N ratio of about 60:1, while grass clippings, manures and food scraps have a ratio of about 20:1 or less, and woody materials often range as high as 500:1. Too much nitrogen in a pile results in the formation of ammonia gas; too much carbon and the pile will take years to break down.

In a practical sense, about two shovelfuls of fresh animal manure to every wheelbarrow load of green plant material, such as weeds and lawn clippings, seems to work well. If you include some paper or dried leaves, add more animal manure. If you cannot access animal manures you can use blood and bone fertilizer or fish meal as your source of nitrogen.

Material |

C:N ratio (weight:weight) |

lawn clippings |

20:1 |

weeds |

19:1 |

paper |

170:1 |

food wastes |

15:1 |

sawdust |

450:1 |

chicken manure |

7:1 |

straw |

100:1 |

seaweed |

25:1 |

cattle manure |

12:1 |

Table 4.1. C:N ratio of common materials.

You need to add enough water so that when you pick some material up it is like a damp sponge, and when you squeeze the material a few drops of water drip out.

About 50% of the pile should be water (you will be surprised how much water is required!). If there is not enough water (<40%), then little decomposition occurs, but too much (>60%), then less air is available in the heap and it becomes anaerobic (without oxygen). Under-watering is the largest single cause of slow composting.

Generally, the more oxygen then the more heat, quicker decomposition, and less smell (and less flies). We want to make the pile aerobic (with oxygen) to enable the pile to really heat up. Anaerobic composting, with very little air in the pile, causes problems such as smells often associated with decomposition (think septic tank).

So, turn the pile as often as you can — once a week for the first three weeks and then leave alone. Turning with less frequency will also result in a good compost product, but will necessarily take longer. However, turning compost too much can waste valuable nutrients into the air and cause the pile to lose too much heat.

Getting enough oxygen is crucial to the success of the hot compost process. A composting grate, at the base of the pile, is a useful strategy to help with this. Placing small stones, twigs or other coarse material on the bottom of the pile or bin allows air to passively move through the pile, providing microorganisms with the oxygen they need to enhance the decay process.

You don’t have to source the special “brew” of compost microorganisms (mainly bacteria) as these are always present in the air and surroundings.

When you start a new compost pile, you can add some “aged” or cured compost from a previous effort. This inoculates the mixed materials with bacteria to “kick-start” the new pile.

While you can buy commercial inoculants, it is far cheaper to use aged compost, dilute urine or herbs such as yarrow, comfrey and borage.

It is believed that these herbs contain high levels of nutrients to help feed the microorganisms, which enables them to build up in high numbers very quickly, but little research has been undertaken on this. It’s up to you to investigate by trial and error.

Plants need soil. They need minerals in soil. You should never just grow plants in pure compost. I know you can, and I have many times, but a soil with only 5% organic matter is more than ample to support plant growth. Compost is expensive so it makes sense to only use it mixed with sand.

While you can just use sand, you should experiment with what you add to the compost pile. Small handfuls of rock or granite dust, loamy soil, crushed limestone and diatomaceous earth all add nutrients to the pile and these are beneficial to growing plants.

Adding sand also helps earthworms — they use the sand grains in their gut to grind dead matter. But be warned: adding lime or too much limestone does more harm than good.

Even though these substances add calcium to the compost, it is not required for composting to proceed.

There is also no need to “neutralize” the acidic nature of the compost as it decays, as well-made compost goes through an acidic stage before it finally balances itself.

There are two aspects to this — the amount (volume) and particle size. The shredding of materials is important. The finer the organic material the faster the decomposition (large surface area to volume ratio (SA:Vol) so microbes can attack all sides).

While it is best to shred the material you use in the compost pile, occasional bulky, woody material, such as wood chips and street-tree prunings, assist in aeration of the pile.

Also a rounded pile has a low SA:Vol ratio so less heat is lost, whereas a long, thin pile has a large SA:Vol ratio and will cool down quickly.

Secondly, piles require a certain critical mass — you need at least 35 ft3 but larger is better. This is a big pile. If the pile is any smaller, it cannot maintain heat, heat escapes and the pile cools down.

Large piles contain the heat longer. This results in better pasteurization and the microbes have more time to degrade any toxins that may come with the raw materials.

You might have to collect enough material over a few weeks before you activate the pile to start the hot decomposition process. The dedicated organic gardener will ask neighbors for their plant prunings and lawn clippings.

Making a compost too big, say 50 to 70 ft3, makes turning and shifting the pile difficult and laborious. There is also a natural tendency to continually add material as you acquire it. The pile slowly builds up. However, this will usually result in passive or cold composting and rarely does the pile heat up or maintain the heat to sustain the compost process.

Some of the problems you may encounter and their solutions are listed opposite.

However, when a compost pile is hot (140°F) and active for several days, it is possible to add small amounts of additional material such as food scraps.

Adding food scraps to the compost pile may be necessary if you have food scraps to deal with, but it is probably better to bury the scraps in the garden and make a new pile whenever you have assembled enough material.

Another reason why it is important to start with a big pile is that during decay the pile shrinks, and as it shrinks it loses heat to the surroundings.

You can monitor the heat of your compost pile by using a compost thermometer. These are long versions of cooking thermometers.

A thermometer takes the guesswork out of when to turn the pile, when different stages of the composting process are occurring and when it is cool enough to use on the garden.

After the compost pile cools down (typically in a month or two), then other creatures invade. These can include earthworms and a host of small invertebrates, such as insects.

Not all insects in a compost pile are “pests,” as the compost ecosystem includes a host of useful invertebrates, including isopods, millipedes, centipedes, worms, and ants among others.

Identifying organisms with a hand lens or microscope is a useful strategy to determine the health of your compost or soil.

Having a few compost bays permits decomposition at various stages.

Problem/issue |

Causes/reasons |

Remedial action |

Bad odor |

Anaerobic pile |

Turn materials to aerate. If too wet, check for proper drainage and mix in dry leaves or straw. |

Insect pests |

Too dry, not mixed properly |

Make sure that if you use food materials they are properly buried in the center of the pile. Use caution if termites are in area — don’t use wood chips, cardboard or newspaper in the pile. |

Pile not breaking down |

Insufficient nitrogen Pile is too dry Poor aeration |

Add grass clippings, manure or some other natural nitrogen source. Add water while turning, until moist. Start turning and mixing materials more often. |

Pile heats up, then stops |

Poor aeration |

Hot piles need lots of fresh oxygen so turn materials as pile starts to cool down. It might be necessary to add a nitrogen source such as animal manure too. |

Weeds growing out of the pile enough |

Pile is too dry, and certainly not hot |

Usually add lots of water to get the right amount to kick-start the composting process. |

Table 4.2. How to solve some of those compost making problems.

Soil amendments are substances that you add to the soil to change its nature. Broadly, there are two categories: chemical-based and biological-based.

Chemical-based amendments are natural rock minerals, chemical salts or manufactured substances readily bought or obtained.

Some of these chemicals are mined and available in their raw state, others are manufactured as by-products of industry or from other ingredients. For example, natural gas can be changed into ammonia, which is then changed again into ammonium nitrate, a fertilizer commonly used on large-scale farms.

Table 4.3 lists some chemical-based amendments and how they can be used.

Table 4.4 lists the types of amendments to use to change particular soils.

Amendment |

|

Too much clay |

Gypsum |

Too much sand |

Bentonite |

Acidic |

Limestone, lime or dolomite |

Alkaline |

Sulfur |

Poor water retention |

Zeolite, spongelite or bentonite |

Poor nutrition — little nutrients |

Rock dust, zeolite, potash, rock phosphate |

Table 4.4. What amendments to use for difficult soils.

Biological-based amendments are those that are produced from once- living things. These substances can be made from dead and decaying organisms, burning organic matter and from the metabolic wastes of animals.

Organic-based materials certainly improve soil structure, as well as providing nutrients to plants and microorganisms in the soil, and Table 4.5 briefly lists some of the different types.

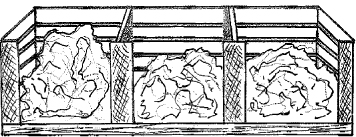

Mulch is something that covers the soil. It is generally the product from shredded plant material, but it also includes other non-plant materials.

Coarse mulches are best for the garden as they allow rain to filter through into the soil below.

Mulch can be either dead material (both organic and inorganic) or a living mulch, and both have advantages and disadvantages.

Organic mulches are produced from organisms, and these are usually plant-based. Animal manure can be used as a mulch, but we think of manures more as fertilizer. Straw, hay, grass clippings, shredded plant materials (e.g. leaves, bark) and pine needles are the most common mulches used in gardens. Organic mulches eventually break down and become nutrients for plants.

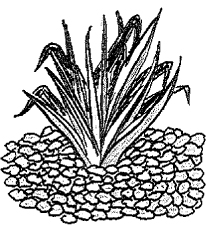

Mulch around a tree.

Mulch is great on garden beds, most of the time. It’s not so great in winter, spring or autumn in areas that suffer frost. The mulch layer prevents the heat held in the soil from escaping (much like a blanket keeping us warm at night) and keeping the air above the ground warm. So frost settles on the mulch and the nearby plants, killing young plants and seedlings and often severely affecting many larger established plants too.

These include natural materials such as stone, gravel and scoria (a volcanic rock), or man made (synthetic) materials such as plastic sheeting (both clear and black), geotextile and vermiculite. Table 4.6 highlights just some of the mulches you can use to protect the soil and conserve water.

A living mulch is a plant that is basically a ground cover. It spreads over an area covering the soil and minimizing the risk of erosion. Usually they are fast growing, thick and hardy; this enables them to smother and out-compete weeds.

A stone mulch still provides protection for a plant.

Some living mulches are planted in a bare area, but others are planted alongside or underneath the main crop. When this occurs, the living mulch may have to be mechanically or chemically killed to enable the main crop to thrive. It is important to manage the competitive relationship between the living mulch plant and the main crop.

The examples of living mulches that follow are generic. Every country has its own plants that are commonly used for this purpose, and there are many plants that become weeds in different environments and different climates and soils. I have found, for example, vetch to be a vigorous ground cover that grows so fast in my soil and climate that it out-competes everything around it for light, nutrients and water. It produces prolific seed so it has spread everywhere on the property. It has become an unwanted plant, a weed. In other soils and climates it may be subdued and manageable.

Sweet potato is an edible living mulch.

Many living mulches are perennials, but some are annuals, and these latter types are best used when you only want a temporary cover while your main crop gets established.

Some that are listed here are herbs, and these tend to be underrated by gardeners. Many herbs are great ground covers and are sun-hardy and tough.

Notes |

|

Hay |

Cut cereal crops or long grass. Often contains seeds, which tend to sprout once you water or it rains. |

Straw |

Cereal stalks (seedhead harvested), little seed. |

Grass clippings |

Temporary mulch. Dries out quickly if thinly applied. |

Street prunings |

Large plant fragments, coarse, relatively cheap, ideal mulch. |

Stone, gravel, scoria |

Useful when no plant material available. |

Plastic sheeting |

Clear plastic film can sometimes be useful to solarize turf and weeds. |

Table 4.6. Common types of mulches.

Living mulch |

Notes |

Clover Trifolium spp* |

Main varieties white and red. N-fixing**, some are annuals, others short-lived perennials, forage. |

Vetch Vicia spp. |

Annual, N-fixing, forage. |

Kidney weed Dichondra repens |

Useful, perennial lawn, but prefers semi-shade, moist areas. |

Pigface Carpobrotus spp. |

Succulent, hardy plant that tolerates full sun, poor soils and windy conditions. Salt-tolerant, edible fruit. |

Sweet potato Ipomoea batatas |

Main types brown and white fleshed (and occasional purple). Besides edible tubers, the leaves are also edible. More nutrition than common potatoes (Solanum sp). |

Nasturtium Tropaeolum majus |

Spread easily. Edible leaves and flowers. |

Fescue Festuca spp. |

Tall, evergreen grass, forage supplement. |

Alfalfa or Lucerne Medicago sativa |

Perennial (5 years), N-fixing, forage. |

Carpeting thymes Thymus spp. |

Also called creeping thymes. Edible leaves, many varieties scented. |

Lawn chamomile Chamaemelum nobile |

Tough, hard-wearing ground cover. Grows in full sun or partial shade. |

* spp. — species. It represents the plural form, i.e. several species.

** N-fixing — nitrogen-fixing.

Table 4.7. Examples of living mulch.

Green manure crops are cover crops. This means that they are grown and then turned into the soil, or cut and allowed to lie on the ground surface. The whole idea is to allow plants to reduce weed growth, protect the soil and provide organic matter for the soil when the main crop is sown.

A catch crop is different again. These are fast-growing plants that are often interplanted between rows of the main crops or between successive seasons of crop (after main crop is harvested and before the next is sown). The classic example is radishes, which are planted between rows of other vegetables. The radishes grow so fast that they can be harvested well before the other vegetables mature.

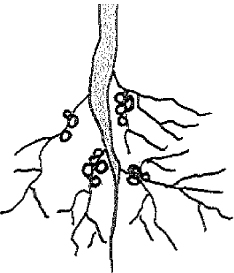

Nitrogen-fixing plants can convert nitrogen from the air into substances that are initially stored in the roots and then used throughout the plant. But the plants themselves cannot do this — they need help from certain bacteria.

Nitrogen-fixing nodules on the roots of a shrub.

» DID YOU KNOW?

The term “pulse” is used to describe any nitrogen-fixing (legume) crops that are grown for their dry seed. This includes beans, peas, lentils and cow pea. Green peas and beans are also classified as vegetables. Some legume crops are also called grains.

There are many different bacterial species that fix nitrogen. These include cyanobacteria, which mainly live in water environments (coral reef); rhizobium, which inhabit legumes (peas, beans, alfalfa, clovers); and Frankia, which are present in alders, casuarinas and all species in the Elaeagnaceae or oleaster family.

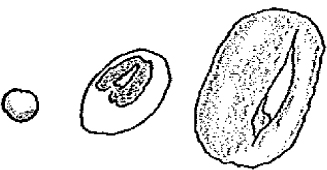

Seeds of warm season nitrogen-fixers. L to R: lentil, cow pea, mung bean.

Using nitrogen-fixing plants as the green manure crop increases the nitrogen concentrations in soils when these plants are killed or cut and dropped.

Some of these plants suit warmer climates and others suit and tolerate colder climates, so these are grouped as warm season or cool season plants in Table 4.8.

» DID YOU KNOW?

Symbiosis occurs when at least two different species coexist and both benefit from the association.

It is very common in nature, and a well-known example is lichen, which is a combination of algae and fungi.

The algae is photosynthetic and makes the food for the fungus (which cannot make its own), while the fungus absorbs moisture to keep the algae alive (algae are seaweeds).

Notes |

|

Cow pea Vigna unguiculata |

High protein, annual food crop, hardy, tolerates shade and dry conditions. Grows in poor soil and drier conditions than many other warm season crops. |

Lablab Lablab purpureus |

Fast-growing annual, edible leaves, beans need cooking. |

Lentil Lens culinaris |

Edible pulse (seeds used as food), high protein content. |

Mung bean Vigna radiata |

Bean eaten as sprouts — raw or cooked. |

Soybean or soya bean Glycine max |

High-protein food, source of soy milk, tofu and oil. |

Cool season nitrogen-fixers |

Notes |

Broad bean Vicia faba |

Tall, annual plants, forage for animals, seeds cooked before eating. |

Chick pea Cicer arietinum |

High-protein seeds, makes hummus, nutritious. |

Lupin Lupinus spp. |

Tall, annual or short-lived perennial plant, forage, nutritious seed. |

Pea Pisum sativum |

Small annual plants, some varieties climbing. |

Subclover Trifolium subteraneum |

Underground seeds, self-regenerating annual, forage. |

Table 4.8. Common nitrogen-fixing green manure crops.

Grain crops are plants that produce small, hard, dry seeds that are harvested for animal or human consumption. They can be cereals (like wheat and barley) or legumes (like soybeans and peas). Cereals belong to the grass family; plants such as amaranth, quinoa and buckwheat are called pseudocereals because they are not true cereals but their grain is used as a staple food.

Soybean

» DID YOU KNOW?

Plants have different photosynthetic pathways. Warm and cool season plants differ in their metabolic pathways and the way in which they use carbon dioxide during the photosynthesis process. They either utilize a three carbon molecule (a C3 plant) or a four carbon molecule (a C4 plant). A few agaves and cacti can utilize either mechanism (and are called CAM plants). Most plants are C3 plants and are adapted to cool season establishment and growth in either wet or dry environments. C4 plants are more suited to warm or hot seasonal conditions under moist or dry environments. C3 plants generally have better feed quality and tolerate frost, but C4 plants tend to demonstrate prolific growth. The succulents of the CAM group can survive in dry and desert areas.

Broad bean

Buckwheat

Warm season grain |

Notes |

Buckwheat Fagopyrum esculentum |

Short season crop, tolerates acidic soils of low fertility but not flooding. Used for erosion control. Buckwheat is a pseudocereal and is not related to wheat or any other grasses. |

Pearl millet Pennisetum glaucum |

Very productive, small-seeded grass. Short growing season, common in tropical countries. Another type that is not related, Japanese millet, Echinochloa esculenta, is grown in poorer soils and cooler climates. |

Sorghum Sorghum bicolor |

Used for alcoholic beverages, biofuel, molasses, food for humans and animals. Drought and heat tolerant. |

Sunn hemp Crotalaria juncea |

Tropical N-fixing plant, useful fodder and fiber. |

Sunflowers Helianthus annuus |

Nutritious seed, good oil. Flowers attract birds and beneficial insects. Some varieties can be very tall. Productive plant. |

Table 4.9. Examples of warm season grain green manure crops.

Notes |

|

Barley Hordeum vulgare |

Common cultivated grain, used to make beer, malt. |

Oats Avena sativa |

Used as oatmeal and rolled oats by humans. Mainly used as livestock feed - both as green pasture and cut as hay. Oat straw for animal bedding. |

Cereal rye Secale cereale |

Rye grain increasingly used for bread, whisky, beer and animal fodder. Also called rye corn. Tolerates poor soils, cold climates. |

Wheat, triticale Triticum spp. |

High protein seed, used to make bread, able to be stored. Grows in low rainfall areas. Hay and straw used in buildings and for animal fodder. Triticale is a hybrid of wheat and rye and is more disease-resistant. |

Canola Brassica spp. |

Several cultivars mainly grown for oil from seeds. Related to broccoli, cabbage and turnip. |

Table 4.10. Examples of cool season grain green manure crops.

When we grow food, we often neglect plant nutrition. We forget that plants take up nutrients from the soil and the soil becomes depleted.

In all agricultural systems, the addition of fertilizer to our soils is crucial to food crop production. We can make simple organic-based fertilizers from weeds, manures, worm castings and various combinations of any or all of these.

In these preparations, bacteria and other microorganisms are used to break down organic matter into simpler substances that can be applied to plants and the soil.

The digestion of plant and animal material can be undertaken without air (anaerobic) or with air (aerobic).

Fermentation, by definition, is an anaerobic process, but we use it here to include any digestion of organic matter, with or without air.

Some bacteria do not require oxygen to survive, and they are able to use plant and animal material as their food source.

When this occurs, various gases are produced as a by-product of the digestion process. These mainly include methane, carbon dioxide and nitrogen, but may also include sulfur oxides, hydrogen sulfide and ammonia.

All of these gases need to be vented from the system, otherwise gas pressure builds up and liquid and gas explosions can occur.

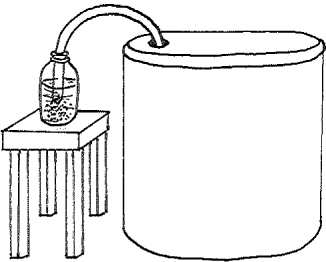

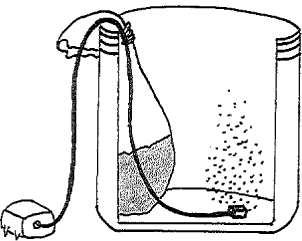

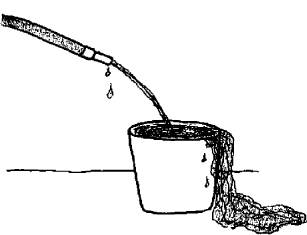

Manure is placed in a drum or container, water is added, along with some other ingredients such as molasses and milk, and allowed to ferment for at least one month and up to a few months depending on climatic conditions. Excess gases are passed out of the tank through a water trap, which excludes air from entering but allows metabolic gases to escape. If these gases cannot escape they build up in the system and inhibit microbe action.

» DID YOU KNOW?

Biofertilizer is a fertilizer that contains living organisms. You basically produce a microbe culture to inoculate the soil and a solution containing readily available minerals to feed the plants. You can “seed” a culture with a particular type of microorganism (e.g. rhizobium, blue-green algae), or you can make a generic brew that contains microbes that are found in the manure, yeast, air and water that you add. You need to use the fertilizer well before the culture dies. Even so, adding minerals and nutrients to plants is beneficial every time.

Biofertilizer is usually made from manure. Most animal manures seem to work, including chicken manure or other bird manures with mixed success. Manure from grass-eating animals, such as cows, sheep and goats, seems better than that from meat-eaters, such as dogs. Pig manure is used to produce methane.

When methane is the main by-product, it can be collected and used as biogas, a fuel that can be used for cooking and heating.

To make a brew, add about 45 lb of fresh manure to a 55 gal drum (with a lid that can be sealed). Fresh manure contains more beneficial bacteria and other microorganisms. Fill to about four-fifths with water.

Anaerobic digestion — makes biofertilizer

Add small amounts of a range of other substances, including milk, yeast, rock dust and molasses, all of which help to kick-start and feed the microbe population. Install a water trap and allow to ferment for a month or two (visible bubbling may stop after a few weeks or more). When you open the lid, beware! — it may stink. If it does smell badly then the product should not be used — it most likely contains pathogens. While biofertilizer does smell, it is not unpleasant — it should smell like a typical ferment.

Pass the liquid through a mesh screen or coarse cloth to remove the digested remains of the manure.

The resulting liquid fertilizer can be diluted at least ten times with water before spraying on the garden. You should be able to find some laboratories that can test your biofertilizer product if you are concerned about its contents.

You will also be able to find other recipes that make biofertilizer, some being specific for particular applications.

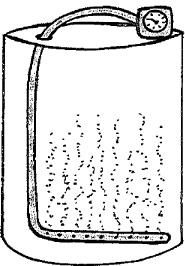

Aerobic microbes need oxygen. Air is pumped into the solution by using an aquarium pump for smaller containers to air compressors (2–3 ft3/min) for larger tanks. Intermediate bulk containers (IBCs) are cheap to obtain second-hand and are ideal. They hold about 275 gal.

Aerobic digestion — makes compost tea

The general term for the products from this process is “compost tea”. You can suspend a bagful of earthworm castings in a 5 gal bucket and aerate for a day or two (generally no more than two days).

On a larger scale, a cereal bag (wheelbarrow-full) of animal manure or shredded weeds and plant material can be aerated by a larger blower or compressor. The drum is open to allow air to escape. Plant material should be finely shredded as much as possible whereas animal manure easily falls apart in water.

A large air compressor can aerate a larger volume of fertilizer.

Compost teas are quick to make, but they must be used at once to maximize their effectiveness and there is an energy cost for the aeration.

Both compost teas and biofertilizer help build soil fertility, and these products can be made from most organic wastes.

The promotion of weeds and plants to indicate certain soil conditions, or as dynamic accumulators that mine particular minerals, should be viewed with caution.

Much of the literature on the role of plants to absorb and store particular nutrients is more folklore than science.

Popular websites and books list tables of dynamic accumulators and lists of common weeds and what they suggest about the structure of the soil, without any reference to sources of information.

There is some evidence, of course, but there appear to be occasional contradictions. Do the plants take up particular nutrients even when these are deficient in the soil, or do the plants simply take up these nutrients because they are abundant in the soil?

Some people suggest that the mineral makeup of plants is a reflection of what’s in the soil, so a plant might have high boron levels because this is present in that soil.

» DID YOU KNOW?

Human body waste is also broken down by anaerobic and aerobic bacteria.

Toilet and other household effluent are decomposed without air in a septic tank system, while on-site aerated treatment plants or municipal wastewater treatment plants use a combination of anaerobic and aerobic bacteria to break down our wastes before discharge or use.

In many cases the treated effluent is used for irrigation.

The remaining sludge and solids are often dried and further composted and changed into various amendments and additives for soil amelioration.

Much of the information about accumulators and indicators is based on historical observations and anecdotal evidence.

Sometimes people do compare chemical soil analysis results with visual observations about the distribution and abundance of weeds in that soil, and I have done this many times, but there is very little research to date about these things.

For example, chickweed is reputed to be an accumulator of manganese and copper, but there doesn’t appear to be any scientific research to support this.

On the other hand, I have observed capeweed in areas of known calcium deficiency, dock, sorrel and plantain in acid soils, barley grass in saline soils or where the water table is high, stinkwort in dry, clayey soils, and lamb’s quarters in rich cultivated soils in summer.

That is not to say that these types of plants are only found in these conditions, so much more research has to be undertaken before we can be confident about using weeds, herbs and other plants as indicators of soil health.

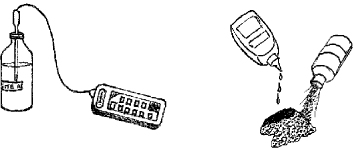

Monitoring and measuring soil components helps us know what amendments to add and what fertilizer we may need to apply. The backyard gardener can perform regular checks on simple parameters such as acidity, and measure the composition of the soil as they endeavor to change it.

pH meter and test kit

Acidity is measured with a pH test kit. pH is the numerical concentration of hydrogen ions placed on a scale 0 to 14, with 7 meaning neutral (not acidic or alkaline = pure water); numbers less than 7 are acid and those greater than 7 are increasing levels of alkalinity (basic).

These numbers are logarithmic, so there is a factor of 10 from one number to the next. For example, pH = 5 is 10 times more acidic than pH = 6.

Most plants like a pH somewhere between 6 and 7.5, although blueberries prefer 5 to 5.5, while asparagus and calendula tolerate 7.5 to 8.5.

An electronic pH meter or a powder test kit can be purchased and easy instructions will enable you to measure the acidity of a soil (or a water source too if a pH meter is used).

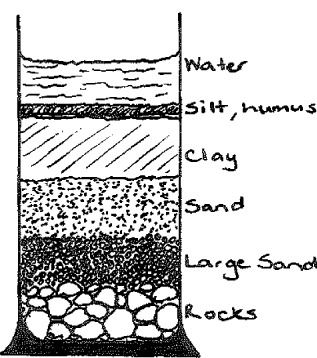

Soil composition can be determined by using specific-sized screens (sieves) or a volumetric cylinder. A sample of soil is passed through a series of screens to separate stone, sand, silt and clay. The amount of each left on each screen will give you a good indication whether the soil is a clayey-loam or a sandy-loam, and so on.

If you have a 500ml or 1l laboratory glass cylinder, you can add soil to the ½ to ¾ way marks. Add water to nearly the top. Stopper and shake to mix thoroughly.

Allow the particles to settle and you can generally see layers of floating organic matter, settled organic matter, fine clays and silts and then coarser sands and stones at the bottom.

Soil profile. Shake soil with water and let settle.

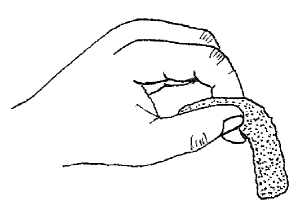

The ribbon test is used to determine soil composition too, and provides information about the clay content.

Here, a small sample of soil and water is mixed in our hand, molding and kneading until a 1 in ball is formed. This is then pushed out between the thumb and forefinger (first finger) into a thin strip.

Measure (estimate) the length of the strip or ribbon when it falls off. Soils with reasonable clay content will produce a 2–3 in ribbon.

A chart that allows you to interpret the soil composition is readily available from books and the web. The feel of the soil while you are molding it also gives us clues about its texture and composition.

Ribbon test

Clay content can also be determined by the bucket method. Place 2 lb (2 l) soil in a laundry 2.5 gal bucket.

Wash the soil with a garden hose and continually stir with one of your hands. The finer clay and silt particles will wash over the edge of the bucket, leaving sand and stone behind.

Once the water is relatively clear, we can assume that clay and silt have been washed out.

Use a bucket and wash all fine material out.

Remeasure (volume or weight) what is left behind and you can do some math to determine the percentage clay content of the soil. This is the test to perform if you want to make mud-bricks (50–80% clay required) or a rammed earth wall (20–50% clay).

While you can do simple tests yourself to determine the acidity and the relative amounts of different particles in a soil sample, you can also send soils to laboratories where they can determine macro- and micronutrient levels, the cation exchange capacity and the degree of salinity.

This type of analysis is important if you want to ensure the correct amount of amendments are added to your soils.

» DID YOU KNOW?

The Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) is a measure of the soil’s ability to hold cations. Cations are positively charged atoms and include three important plant nutrients: calcium (Ca2+), magnesium (Mg2+) and potassium (K+).

Cations are held by negatively charged particles, called colloids, which are common in clay and humus. The humus found in organic-rich soils can hold about three times more cations than the best type of clay.

As plants take up the cation nutrients, other cations take their place on the colloid. The stronger the colloid’s negative charge, the greater its capacity to hold onto and exchange cations (hence the term Cation Exchange Capacity).

The CEC is a good indicator of soil fertility, as a high CEC suggests many nutrients may be available to plants.