The Experience of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementia

What is it like to have Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia? What would it be like to be unsure of your surroundings, to have difficulty communicating, to not recognize a once-familiar face, or to be unable to do things you have always enjoyed? When you understand the world of people with dementia, you can begin to understand their experiences, develop empathy, and relate better to their situations.

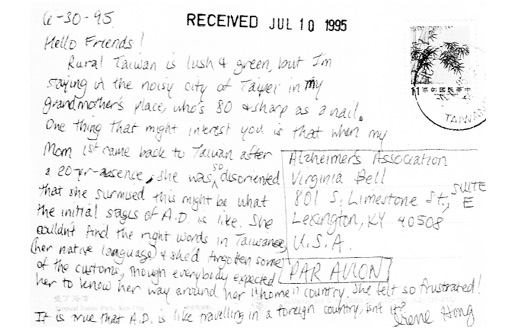

The experience of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia can be like taking a trip to a foreign country where you don’t speak the language. Customs are different. Deciphering a restaurant menu proves difficult; you may think you are ordering soup and end up with fish! When paying a restaurant bill with unfamiliar currency you might fear that you are being shortchanged, cheated. Tasks so easy at home are major challenges in an unfamiliar setting and can be exhausting. The person with dementia is in a foreign land all the time, as seen in Irene Hong’s postcard.

Hello Friends:

Rural Taiwan is lush and green but I’m staying in the noisy city of Taipei in my grandmother’s place who is 80 and sharp as a nail. One thing that might interest you is that when my Mom first came back to Taiwan after a 20 year absence, she was so disoriented that she surmised this might be what the initial stages of Alzheimer’s is like. She couldn’t find the right words in Taiwanese (her native language) and she’d forgotten some of the customs though everybody expected her to know her way around her “home” country. She felt so frustrated. It is true that Alzheimer’s disease is like traveling in a foreign country, isn’t it?

Irene Hong, volunteer, Postcard sent to Helping Hand Day Center

Rebecca Riley was one of our early teachers about the experience of dementia. A nurse and educator, Rebecca was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease at age 59. When she first began having difficulty teaching, she thought it was because the course content was new. Soon, she knew something was wrong with her thinking and memory, and she suspected that she might have Alzheimer’s disease. Her physician later confirmed her suspicions. Rebecca taught us about the world of dementia. Following are some of her written notes describing her experience:

- Depression

- Can’t say what I want

- Afraid I can’t express my thoughts and words—thus I remain silent and become depressed

- I need conversation to be slowly

- It is difficult to follow conversation with so much noise

- I feel that people turn me off because I cannot express myself

- I dislike social workers, nurses, and friends who do not treat me as a real person

- It is difficult to live one day at a time

Rebecca knew that she was losing her language skills and the ability to communicate her wishes. Her writing reveals that her once-meticulous grammar was slipping. Complexity became her enemy; she could not follow the din and roar of competing conversations—calling it “noise.” Her statement about social workers, nurses, and friends who do not treat her as a “real person” still makes us both smile and wince. Even though her cognitive skills were in decline, she recognized that people were treating her differently. Consequently, she expressed her anger and some resentment toward these people. Remarkably, she was trying to create a plan for the future. Her notes indicate that she was deciding to take things “one day at a time” even if it was a struggle.

Reading these heartfelt words, you too can begin to understand the experience of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia. Without understanding this world, we cannot possibly develop successful strategies for improving the lives of our friends or loved ones with dementia.

Emotions That Accompany Alzheimer’s Disease

Persons with dementia commonly experience these emotions and feelings:

- Worry and anxiety

- Frustration

- Confusion

- Loss

- Sadness

- Embarrassment

- Paranoia

- Fear

- Anger

- Isolation and loneliness

COMMON EMOTIONS AND FEELINGS OF PERSONS WITH ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE AND OTHER DEMENTIA

Every person’s response to Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia is different, but many people will experience one or more of the following emotions.

Worry and Anxiety

We all worry or become anxious at times. Parents worry and become anxious about their teenager who is not home by curfew. Families may worry about having enough money to pay all of their bills at the end of the month. Some people worry that a favorite celebrity’s marriage is in trouble after reading the latest tabloid at the supermarket.

The person with dementia can become consumed by worry and anxiety. One frequent by-product of dementia is that the person cannot separate a small worry from an all-consuming concern. For example, a person with dementia may begin worrying about dark clouds in the sky seen through a window. Left unchecked, the worry can grow and wreck his or her afternoon. A spring shower could turn into a thunderstorm!

Harry Nelson was a practicing dentist when he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in his mid-fifties. He was very anxious about his life and the lives of his family. He worried, when in spite of his determination to keep fit mentally, spiritually, and physically, his scores on his mental exam kept going down. He worried that he would not be able to go hiking with his grandson when he became old enough to enjoy a sport that he loved. His dreams and aspirations were on hold, and he had difficulty not being anxious about the future.

Harry’s worries are typical of many people with dementia. They may become upset if they think they’re not meeting their employment obligations or are late for work. This makes sense: work consumes much of our lives, and it’s understandable that this part of a person’s life will still resurface on occasion.

Frustration

Almost all of us occasionally misplace car keys. The keys turn up eventually, but the search can be very frustrating. Imagine the frustration of losing your keys or wallet every day, every hour.

Because short-term memory is attacked, the person with dementia may constantly be looking for something he or she is certain has been misplaced. Frustration may also stem from failing to complete everyday tasks. In the morning, a thoughtful care partner may leave clothes on the bed for her mother with Alzheimer’s disease. Her mother stares at the underwear, blouse, a skirt, a sweater, shoes, and jewelry. What goes on first? What may have once been so simple is now an elaborate series of steps performed in a certain sequence: put on the hose before the shoes, the bra before the blouse. Yet, because she loses her ability to sequence, this woman with dementia finds that the simple act of dressing is extremely frustrating. On top of this, the person is easily tired out or exhausted by the extra effort and concentration it takes to complete a once routine task.

Accustomed to using his reasoning and problem-solving abilities in his work, Brevard Crihfield or “Crihf,” the former executive director of the Council of State Governments, summed up his experience of Alzheimer’s disease when he said in frustration, “It is like my head is a big knob turned to off.”

Crihf’s description of Alzheimer’s disease remains one of the best we’ve heard; it is powerful and articulate.

Confusion

What do you think when a friend does not show up for a lunch date? Maybe one of you got the time and date mixed up. You hope nothing serious has happened, so you try calling your friend’s cell phone, and the mystery is solved—you have gone to different restaurants! The confusion has been cleared up, but if your friend had not answered his telephone, you would still be at the restaurant, waiting impatiently.

For many people with dementia, confusion is a daily experience. The person is never quite sure about anything—the time of day, the place, and the people around him or her. Also, unlike the above example, people with dementia often cannot sort out or work their way through the confused state.

Ruby Mae and a volunteer at a day center were looking at a photo album. “Look, Ruby Mae, you are dancing with a handsome young man.” Ruby Mae loved a good time and seemed to be enjoying reliving some fun times. When it was time to eat, she insisted that they bring “him” to lunch, too. “Him?” the friend wondered. “You know that nice one we were just dancing with. He’s hungry too,” Ruby Mae replied.

Ruby Mae was profoundly confused, but she kept her sense of humor throughout her long journey with Alzheimer’s disease.

Loss

Many of us define ourselves by our jobs, our relationships, or the things we do. You might say, “I am proud to be a good carpenter,” “I am Wayne’s mother/father,” or “I am a fly fisherman.” If any of us had to make a major change in life and these roles were taken from us, we would experience feelings of great loss.

People with dementia lose these titles and, as a result, lose important and meaningful roles. Eventually, they will be unable to work and will have to give up favorite activities. Sooner or later, the losses mount.

Sometimes, as care partners, we tend to focus on our own losses (e.g., the relationship, the time consumed by caregiving, the hard work that can accompany physical care) and forget to acknowledge the losses of the person. But it is important to remember that the person with dementia experiences painful loss day after day.

Learning to Understand

A simple exercise can help you begin to understand the impact of dementia. Take five small pieces of paper. On each piece, write one of your favorite activities. A typical activity might be visiting the grandchildren, taking a day trip in the car, enjoying a favorite hobby, going to work, trying a new recipe, playing golf, or talking on the phone with an old friend. After you are through, select an activity, think about how much you enjoy it, and then imagine giving it up. Take the piece of paper listing the activity, wad it up, and throw it away. Continue to do this until you have discarded all five pieces. How do you feel?

The odds are that you are now experiencing the feelings of loss that many with dementia feel. Sadly their losses are real, not “paper losses.” Worse, they cannot choose the things to give up. That choice has been made by Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia.

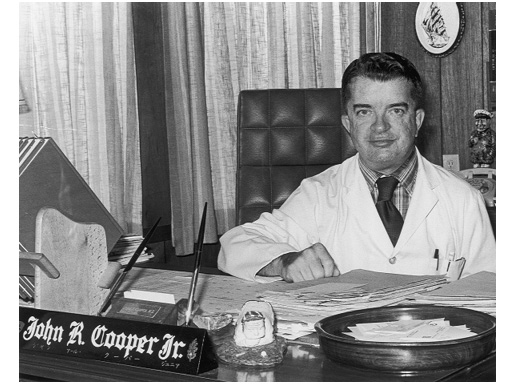

Dr. John “Jack” Cooper had a distinguished career as a Navy commander and surgeon. He would say, “I don’t have a job. I don’t have any money. I don’t have my life anymore.”

In spite of Jack’s many losses, he still remembered being and was very proud to be a physician. He preferred to be called “Jack” day-to-day, but liked to be introduced as “Dr. Cooper” on special occasions.

Dr. John Cooper at the height of his medical career, 1971

Sadness

All of us experience moments of sadness. Perhaps you remember a failed relationship or the loss of a beloved pet. Maybe a poignant story on the news makes you teary. Sadness can be fleeting, or it can be long-lasting and associated with a profound grief process. Like happiness, sadness is a part of life.

Feelings of sadness are often pervasive among people with dementia. A person can burst into tears at the thought of not being able to tell a story all the way through or at forgetting a name. A person can also feel sad over long-term losses, such as having to move out of a family home. People who do not have dementia can develop strategies to overcome sadness (seek therapy, call friends, go for a hike); people with dementia lose this ability to work their way out of sadness.

Geri Greenway was at the peak of her career as a college professor when she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in her late forties. Aware of the nature of the disease, she often sat with her hands covering her eyes, as if her world was too painful to see.

Being diagnosed so young created intense feelings of sadness for Geri, but she responded enthusiastically to smiles, hugs, and friendly, reassuring words.

Embarrassment

All of us can remember a time in school when the teacher called on us and we did not know the answer to a question. You might recall your collar tightening, voice faltering, palms sweating, and face blushing.

The person with dementia is in a giant classroom every day, one in which he or she never has the exact answer. A woman who always prided herself on her appearance may have someone point out that she is wearing her jacket inside out. Names are easily forgotten. Embarrassment is common for persons with dementia, particularly those who are more aware of their mistakes.

“There she is! When did she come in? That’s my wife over there.” Hobert Elam was sure that he had spotted his wife at the day center at a table across the room. When he approached her, he realized it was not his wife and was very embarrassed. “I can’t believe that I made that mistake,” he admitted to a volunteer at the program.

Mixing up identities is a common occurrence for people with dementia. They begin to forget faces and sometimes can be confused when people look alike. They may confuse genders, thinking a woman with short hair is a man and that a man with long hair is a woman. Declining vision and hearing can make the situation worse. When the person knows he or she has made a mistake, it can be embarrassing.

Paranoia

If your boss starts treating you differently, you may wonder if he or she is unhappy with your performance. If you see a strange car outside your house several days in a row or if someone is standing too close to you at the ATM as you’re withdrawing money, you may become alarmed. Even the most well-grounded individual becomes a bit paranoid in some circumstances.

People with dementia often look for an explanation about what is happening to them. Why does their family refuse to let them drive? Where is their money? When they cannot find rational explanations, they sometimes experience bouts of paranoia, imagining that someone is trying to harm or hurt them in some way. Delusions or fixed, false ideas are extremely common in persons with the most common dementia, Alzheimer’s disease. Paranoia can be a by-product of these delusions.

Emma Simpson kept complaining to her daughter, Patricia, that the woman next door was taking her scissors. Emma was sure of it because she could never find a pair of scissors when she needed them. One day, Patricia moved her mother’s purse and it was heavier than she could imagine. She began unloading the purse and found seventeen pairs of scissors of every kind, color, and description, making the purse bulge at the seams.

Hoarding or hiding things is common for persons with dementia. They may be paranoid that someone is stealing things or simply be trying to keep track of their valued possessions, like Emma.

Fear

All of us become fearful now and then. Perhaps you’re walking in a big city late at night and hear footsteps behind you. Maybe you’re afraid of earthquakes or tornadoes, spiders or snakes.

Individuals with dementia also have fears. These may include the loss of independence, placing too much burden on family members, and getting lost. Other fears might include traumas from the past that have risen again in the present (e.g., thinking that a Vietnam War event is still happening) and fears caused by delusions (someone is stealing their money). Misperceptions of vision or space can subsequently lead to a fear of falling, particularly if the carpeting on the floor has a confusing or misleading pattern.

Sisters Henrietta and Mae Frazier lived together for many years. Henrietta’s cheerful disposition made it easier for her sister to care for her—except that after her diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease Henrietta developed a terrible fear of bathing. Whether it was the running water, the cold porcelain tub, or some past trauma, she was often reduced to tears when being helped with her bath.

Mae was able to address this fear by hiring a particularly sensitive home health aide, who took plenty of time and built a trusting relationship with Henrietta. (See page 190 for some ideas about bathing.)

Anger

All of us get angry occasionally, and although no one wants to bear the brunt of it, anger has a constructive purpose: It can help us fight a battle if threatened. It can release harmful stress and pent-up emotion. Also, sometimes getting something off your chest by becoming angry can lead to healing in relationships.

It is a myth that all, or even most, people with Alzheimer’s disease are violent. Yet people with dementia can become angry. They may not always understand what is happening around them and to them. Anger can also stem from a loss of control when they feel rushed or unduly pressured to do something.

“You go home!” Annie yells if angered. Her husband, Jack Holman, says that she has always been very independent, and that now, having to depend on others for all her needs is really difficult for her. Because of her Alzheimer’s disease, her vocabulary is very limited, but she still can find words to express herself when she becomes angry.

Persons like Annie may continue to have angry moments, but learning to use the Best Friends approach can help care partners understand the triggers for her anger and learn ways to cope.

Isolation and Loneliness

A friend of the authors hurt his leg in a skiing accident and had to curtail most of his activities for a month. He could not go to the office, could not work out at the gym, had to give up his opera tickets, and had to cancel outings with friends. He told us that he was very lonely during his recuperation. His first day back at work was one of the happiest of his life.

As Alzheimer’s disease progresses, isolation and loneliness often increase. The person can no longer drive and may no longer be able to play a weekly bridge game, go sailing with friends, do woodworking, go shopping, or even walk down to the neighborhood doughnut shop. The person loses social contacts; worse yet, friends eventually stop visiting. Unlike a broken leg, the person’s memory cannot be mended.

A former teacher and community leader, Rubena Dean often felt left out of activities. She once said, “I used to play cards, I used to drive, I used to work . . . there are too many ‘used tos’ in my life now.”

Despite not knowing who the president of the United States was, what day it was, or even how old she was, Rubena was surprisingly articulate about what it is like to have dementia.

Early-Stage Support Groups

More and more organizations are now offering support groups not just for caregivers but also for individuals with dementia. These groups range from social, “club-like” meetings to ones that include more therapeutic elements. The individual with dementia responds to the camaraderie, the humor, the sharing, and the feeling that he or she is not alone. Even families who thought that their loved ones would never try such a group have been impressed. Another variation on these groups is what some groups call a “Memory Café.” Learn about that program on page 228.

With dementia, friends tend to fall away. When a person with dementia meets another person going through the same experience, an instant friendship often forms and feelings can be shared and discussed.

Several books and newsletters are available that discuss these groups and are listed under Organizations, Websites, and Recommended Readings (page 283).

THE BEST FRIENDS APPROACH

Now that you’ve read this chapter, take a moment to imagine what it is like to have dementia. Try doing the simple Learning to Understand exercise (page 20)—it is a powerful tool for care partners and can help you better understand the person’s frustration and anger.

You are a lucky care partner if you do not bear the brunt of these feelings from time to time. Fortunately, many people with dementia also feel happy and joyful at times. These feelings can be momentary or long-lasting. Sometimes the very losses of dementia provide a level of emotional protection that insulates them from the problems of the world, their family, or even their disease. Thus, the person with dementia can have moments throughout the day when he or she is enjoying the company of a pet, savoring a piece of chocolate, laughing at a joke, or celebrating a mutual hug. Sometimes with humor and sometimes with guilt, care partners have admitted in support groups that their loved one’s personality has changed for the better. The overachieving, aggressive, “type-A” father sometimes becomes more playful; the pessimistic aunt becomes an optimist; the uptight, controlling mother learns to relax.

CONCLUSION

This book outlines the Best Friends approach to caring for a loved one with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia. The Best Friends approach can help you understand the feelings expressed by people with dementia. As the saying goes, to understand someone, you must “walk a mile in his shoes.” When you walk this mile—or run this marathon, as many care partners feel—you begin to see one of the underlying surprises of this book: The so-called inappropriate behaviors of dementia are not all that mysterious or out of place. They often stem from the person’s efforts to make sense of his or her world, to navigate the maze of dementia. If any of us experienced memory or judgment problems, if any of us were afraid of something, if any of us had to give up most or all of our favorite activities, it would be perfectly normal to be sad or anxious, to hide things, to wander away from a possibly threatening situation, to leave the house if we think we’re late for work, or to strike out at someone we think is trying to hurt us.

Once you understand what underlies the challenging behaviors, you begin to see dementia care in a new light. The Best Friends approach helps you gain this perspective. And remember: because the person’s medical condition will not change, it is we, as friends and family, who must change.

Best Friends Pointers

- Feelings of loss, confusion, frustration, and anger can be normal feelings caused by dementia.

- People with dementia are working very hard to make sense of their world, to see through this confusion and memory loss.

- Taking time to think about the experience of the person helps us overcome denial, develop empathy, and be a more supportive and effective care partner.