Basic Principles of Dementia Care

In families, residential care programs, adult day centers, and in-home care situations around the world, you find people who stand out, who seem to have a “magic touch” in their work with, or care of, persons with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia. These situations include:

- The beloved nursing assistant who can rise to any occasion and always seems to say or do the right thing.

- The adult son who does things he never dreamed he could and now helps his mother with personal care, including bathing and dressing.

- The husband who gives loving care to his wife, uses local services, and approaches his tasks in a joyful way, seemingly avoiding the burnout that affects so many care partners.

- The nursing home activities director who is always coming up with ideas for a consistently rich and innovative activity program.

- The in-home worker who knocks on the door, smiles, gives the person with dementia a hug, and builds a great relationship with the person he or she is helping.

What is the difference between care partners who struggle and care partners who succeed? Some of us have more financial resources to draw on, which can make a positive difference. A large and supportive family can help. In professional settings, a liberal budget and successful volunteer program can enrich programs. Yet some care partners and some institutions with almost unlimited resources still struggle, while others with limited resources thrive.

The individuals and institutions who succeed have mastered the “knack” of caregiving. We define “knack” as the art of doing difficult things with ease or clever tricks or strategies. Some individuals are simply born with knack; their personality and sensibility help them to be wonderful care partners. Cynthia Lilly, National Memory Care and Dementia Program Director for Atria Senior Living, has the knack:

I always make the most of my first five minutes with a person with dementia, particularly if I’m trying to encourage them to do something like come to lunch or attend an exercise class. I find that when I greet them by name, approach them with a smile or hug, use their Life Story, and try to really be present for them, everything goes better. The “no” becomes a “yes.” Sometimes these five minutes save thirty minutes; sometimes it saves the whole day!

Families struggling with a person who has behaviors that are challenging will do well to remember Cynthia’s five-minute strategy. Getting off to a positive start fosters cooperation and can help you get a task like dressing or bathing accomplished.

Even if you are not sure if you have the knack, anyone can improve their dementia caregiving by understanding some basic ingredients and how they are used.

THE INGREDIENTS OF KNACK

The knack of caring for a person with dementia comes from possessing many skills and abilities—ones that will come to you once you see how they work and have the chance to practice them. The following are the elements of knack that are central to the Best Friends approach.

Being Well-Informed

Care partners with knack learn as much as they can about dementia in order to be better informed of new research and treatments, to learn caregiving tips, and to locate new community resources. They attend conferences and workshops, study reputable websites, subscribe to appropriate newsletters, and talk to other families coping with dementia. They recognize that the more one knows about dementia, the less stressful the difficult job of caregiving becomes.

Having Empathy

Care partners with knack have taken time to imagine what it would be like to have dementia. This helps friends and families understand the world of the person in their care and how that world can be difficult and frightening. Empathy also teaches that many of the person’s odd or upsetting behaviors are caused by their attempts to make sense of their world—a world clouded by dementia.

Respecting the Basic Rights of the Person

Care partners with knack regard persons with dementia as individuals who deserve loving, high-quality care. They give persons as much say in their care as possible and try to keep them productive in work and play as long as is realistic. They use the Alzheimer’s Disease Bill of Rights (see page 55) as their touchstone.

Maintaining Integrity

Care partners with knack approach problems and decision making with an attitude of goodwill toward the person, and they approach care in an ethical fashion. When they withhold information or work their way out of problematic situations, they do so out of concern and in the best interests of the person. For example, a care partner who decides not to tell her mother that they are going to visit an adult day center for the first time and “surprises” her mother with the visit may in fact be withholding information, but this decision is made with integrity.

Employing Finesse

Care partners with knack are able to utilize the art of finesse to respond to difficult situations. They use skillful, subtle, tactful, diplomatic, and well-timed maneuvers to handle problems. In the game of bridge, finesse is taking a trick economically. The same holds true in dementia care; as care partners we want to win a few hands. If a person says “I want to go home,” and you respond “Soon,” you are using finesse to give the person the answer he or she wants to hear. Some family members struggle with this strategy, feeling that they are lying or being deceitful. As long as care partner integrity is maintained, the authors believe that skillful finesse is part of good dementia care.

Elements of Knack

Knack is the art of doing difficult things with ease or clever tricks and strategies. The elements of knack include:

Being well-informed

Having empathy

Respecting the basic rights of the person

Maintaining integrity

Employing finesse

Knowing it is easier to get forgiveness than to get permission

Using common sense

Communicating skillfully

Maintaining optimism

Setting realistic expectations

Using humor

Employing spontaneity

Maintaining patience

Developing flexibility

Staying focused

Being nonjudgmental

Valuing the moment

Maintaining self-confidence

Using cueing tied to the Life Story

Connecting with the spiritual

Taking care of oneself

Planning ahead

From The Best Friends Approach to Alzheimer’s Care, © 2003, Health Professions Press. Used with permission.

Knowing It Is Easier to Get Forgiveness Than to Get Permission

Care partners with knack know that sometimes decisions must be made for the person. They know that asking permission works with a person with intact cognitive abilities but is not always the best option with someone who has dementia. When the person does become angry or upset at the care partner for making a decision (for example, throwing dirty clothes in the laundry or cleaning up a messy house), you may find it expedient to simply “take the blame” or apologize for the “misunderstanding.” The person will soon forget the incident, but meanwhile you have been able to take care of a task that needed doing.

Using Common Sense

Care partners with knack exercise common sense. They are not afraid to seek simple solutions to complex problems. Examples of commonsense ideas you can try include: eliminating caffeine when the person has problems sleeping, making extra sets of keys in case a set is hidden or lost, having the person wear an identification bracelet, not making a fuss over things that really don’t matter, and making extra photographs of the person to share with others in case he or she wanders away.

Communicating Skillfully

Care partners with knack communicate skillfully, cueing the person with appropriate words from his or her Life Story, using positive body language, and knowing the right and wrong ways to ask and answer questions. Good communication also involves skillful listening, and the best care partners work hard to help the person better communicate. Find out more about communication in Chapter 7.

Maintaining Optimism

Care partners with knack try to look beyond dementia and remember the good things in life. They take joy in even small pleasures that can come from time spent with their loved one with dementia. Care partners maintain a sense of hope that the future will be brighter and that one day a cure for Alzheimer’s disease will be found. They try to instill this sense of optimism and hope in the person with the disease.

Setting Realistic Expectations

Expectations that are too high or too low can be frustrating to both care partner and the person. Be realistic. What can the person still do and enjoy? What tasks will lead to success or satisfaction? What might prove frustrating or evoke failure? Achieving this balance is part of the art of knack.

Using Humor

Care partners with knack are not afraid to tell funny stories and jokes, or to laugh when humorous things happen. They understand that even when the person does not “get” a funny story or joke, laughter and good feelings are contagious. The person will absorb these good feelings. Another key element of humor is that care partners should not be afraid to make fun of themselves. Self-deprecation preserves dignity and is a small price to pay to make the person feel better about his or her own circumstances.

Employing Spontaneity

Although persons with dementia do respond to routines, they don’t like strict schedules! After all, the schedule is someone else’s planning, not theirs. A day of working in the garden planned by the care partner might get interrupted by an hour of unplanned bird watching when colorful cardinals are spotted in the trees. Go with the flow sometimes! It is healthy for the person and for you.

Maintaining Patience

Care partners with knack realize that it takes the person longer to do things and longer to respond to words and events. The act of dressing can take an hour, but it may be an hour during which the person is focused and does not feel lost or lonely. If you do not have an hour to spend helping the person dress, creative solutions can make life run smoother (e.g., use clothes with Velcro fasteners or simplified outfits). All of us occasionally lose our patience, but getting frustrated and angry tends to make matters worse.

Developing Flexibility

It is important to examine oneself and develop greater flexibility as a care partner. Some individuals have lived their lives with great discipline, getting things done on time and adhering to a schedule. This tendency may be helpful in many ways but not if the care partner is rigid or inflexible; persons with dementia want to set their own pace.

Staying Focused

Care partners with knack learn the importance of focus. With all of the distractions around us, it can be hard at times to give the person the attention needed to provide good care. The knack of focus involves really listening to and seeing the person and getting the most out of every interaction. For instance, when helping a person get dressed, turn off the television and take the time to be together and decide together on what colors to wear. Focus also involves putting your own concerns or problems on hold during this time. Anxiety in the care partner, for example, can show up in facial expressions or in vocal tones and can be misread or misunderstood by the person.

Being Nonjudgmental

Care partners with knack work on being nonjudgmental toward the person, family, friends, and themselves. Stress and strain are inherent in caregiving, and they can be increased when friends and family are not always present when needed, or say the wrong thing, or let you down. Of course, it can be very easy to be angry at or disappointed in the person despite the care partner’s best intentions. Care partners may not always be at their best either and must learn not to be too hard on themselves.

Valuing the Moment

Care partners with knack know the importance of living in and valuing the moment. A pleasant lunch, time spent arranging flowers, or a fun game of cards may soon be forgotten, but it can be pleasurable for everyone in the moment. This seems particularly important when discussing dementia because affected individuals often lose the past and don’t think about the future—the moment is all they have.

Maintaining Self-Confidence

Care partners with knack exhibit self-confidence in their interactions with the person. To be confident, we need to feel that we know what we are doing, have a plan of action, and have some successes to make us feel that we are doing the right thing. Often, this inner strength can be sensed by the person, who may then let go of his or her own concerns or fears. Conversely, if care partners, family members, or professionals are tentative in their actions, the person may sense these feelings and become uneasy.

Using Cueing Tied to the Life Story

Care partners with knack are able to incorporate the Life Story into all aspects of care, cueing the person to remember certain names, places, and things; telling familiar stories; and reminding him or her of past achievements. Even using just a few facts from the person’s Life Story can improve the caregiving environment and encourage cooperation.

Connecting with the Spiritual

Care partners with knack fulfill their own spiritual or religious needs and realize that the person also has a need to be loved, appreciated, and known, even though he or she may have to depend upon others to help fulfill these needs. See Chapter 9 for a more extended discussion about the impact of dementia on spirituality and religious practices.

Taking Care of Yourself

Care partners with knack find time for themselves to maintain friendships, exercise, and eat well; they do not let their identity become totally wrapped up in the caregiving role. They attend support groups for emotional support and community connections. They learn more about dementia through conferences and workshops. Look for more information about being your own best friend in Chapter 11.

Planning Ahead

Care partners with knack identify and utilize local services sooner rather than later. Also, care partners with knack have made it a priority to put the person’s financial and legal affairs in order. This process should include a contingency plan in case the care partner becomes incapacitated or dies. Who will then care for the person? These are important decisions that should not be neglected by the primary care partner.

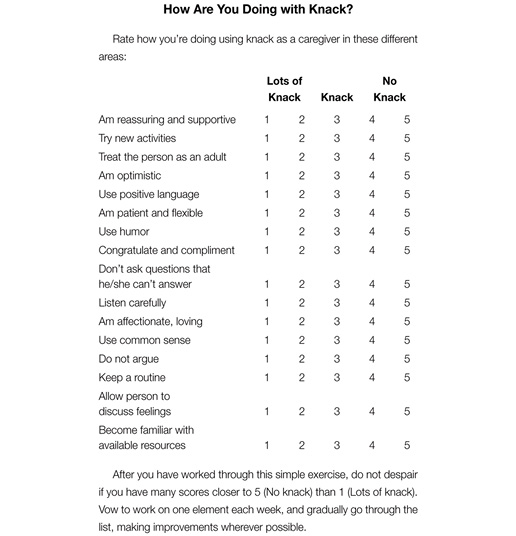

LET’S PRACTICE KNACK IN DEMENTIA CARE

Following are some common scenarios that care partners encounter when dealing with individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia. A number of situations are presented comparing dementia care that has “no knack” to that with “knack.” Some of the common threads running through all the examples are good listening, empathy, humor, creativity, skilled communication, and lots of patience. Remember, if you have met one person with Alzheimer’s disease, you have met only one person with Alzheimer’s disease; every individual and every situation is different. Thus, the following examples may or may not be appropriate to all situations. We hope readers will be inspired by these examples of knack, or dementia care at its best, and apply the lessons to their own situations.

Desire to Go Home

A wife is perplexed that her husband wants to go home, even though he is at the house they have lived in for twenty years. She cannot imagine why he feels like a stranger in his own home. He often says, “I want to go home, I want to go home.”

No-Knack Approach

“This is your home and has been for twenty years! I can get the deed out of the files to show you. Remember how we worked so hard to pay for this property?”

Caregiving with Knack

“Tell me more about that big red brick house of yours in Milwaukee. Tell me about home.”

Why It Works

The no-knack approach demonstrates the futility of trying to win an argument with a person with dementia or explain things in detail. The husband probably picked up the wife’s agitated and frustrated tone of voice. He really thinks he is not at home, or he is remembering a different home from his past, or his words might not have literal meaning and be more about a feeling than a place.

The approach with knack allows for the possibility that wanting to go home may mean getting back to where things make sense again. Asking him to say more about it might give him room to talk more about his feelings or describe the home. Perhaps after some discussion he will move on to another topic or be satisfied.

Feelings of Sadness

“I’m very sad today. Nobody loves me anymore,” a mother says to her daughter-in-law.

No-Knack Approach

“I don’t think it’s good to feel sorry for yourself. You’ve got so much to be thankful for. You’ve got lots of family, including your granddaughter, Kimiko, in Japan who is visiting you soon, your cousins in Ohio, and your sister in New York. You were happy yesterday; just try to enjoy yourself today.”

Caregiving with Knack

“I’m sorry you’re feeling blue today. I feel that way now and then too, but you know you are my friend, and I love you a whole bunch. Your granddaughter, Kimiko, will be coming soon. That should be lots of fun.”

Why It Works

The no-knack response fails to acknowledge the person’s feelings. The daughter-in-law presents too much information to the person all at once. Telling a person, in effect, to “Shape up!” is usually not helpful in any situation where someone is feeling blue.

The approach with knack affirms the person’s feelings of loneliness—not judging, just listening and accepting. We don’t always need to “cheer up” a person with dementia; sadness is part of life. The daughter-in-law admits having similar feelings, which helps the person believe that she is not alone, that these feelings happen to all of us. Her statement of love is heartwarming and uplifting.

Problems with Bathing

A family is exasperated because their mother struggles with them when it’s time for her bath. She insists she has already bathed that day or makes other excuses. When they finally get her in the shower or tub, the bathing process is another struggle.

No-Knack Approach

“Mom, if you don’t get into the tub we’ll have to put you in a nursing home. You stink! Don’t you have any pride anymore?”

Caregiving with Knack

Prepare the bath in advance, and use a calm tone of voice. Use some positive language such as, “It is time to go to the spa,” or “Let’s clean up before going out to lunch.” Ask the doctor to write an “Rx” or “prescription” for bathing. Jump in the shower with Mom or try sponge baths (which can still be effective).

Why It Works

The no-knack approach fails to understand the fears that a person with memory loss and confusion can have about bathing. The person may associate bathing with being cold, uncomfortable, embarrassed, or out of control. The bullying will only make matters worse. The approach with knack shows preparedness and creativity. Here, the care partner understands that a gentle touch may be best.

Sexual Behavior

One of the most upsetting experiences for a care partner is when the person makes an inappropriate sexual advance. What should happen if a man with dementia makes a sexual advance toward his daughter?

No-Knack Approach

Angry and distressed, the daughter says, “What’s wrong with you? Stop that immediately!”

Caregiving with Knack

“Daddy, it’s Mary, your daughter. Look what I have here—a photograph of Mother. Isn’t she pretty?”

Why It Works

The no-knack approach fails to recognize that the person is most likely confused about identity; daughters often look like their mothers, and he may be remembering himself as a much younger man. If the person thinks his daughter is his wife, his behavior does not seem so out of the ordinary.

The above response with knack is a sensitive one in so many ways. The daughter clearly identifies herself in one sentence by saying, “Daddy, it’s Mary, your daughter.” Then, by showing her father a picture of her mother, she provides further cueing about roles and identities. Finally, the daughter approaches the situation in a calm, nonjudgmental fashion.

It is also important to note that sometimes the label of sexual inappropriateness is applied incorrectly. If a person begins undressing, it might be because he or she is too warm. A man might unzip his pants to go to the bathroom, not to expose himself.

Angry Outbursts

A mother yells at her son who is visiting her at her assisted living home, “You are late. I’ve been waiting for you for hours. I am so angry at you!” (The son isn’t late. He always visits around dinnertime, but his mother has lost track of time.)

No-Knack Approach

“Mom, I’m not late. I always visit you at dinner. You haven’t been waiting for hours and I’m hurt that you’d get angry at me when I always come to visit you.”

Caregiving with Knack

“Mom, I’m so sorry. The traffic was terrible. I’ll do better next time. I love you!”

Why It Works

The no-knack approach doesn’t solve anything and it reminds his mother about her disability. It may make the son feel better in the moment to get his feelings off his chest, but does it help the situation to prove that Mom is wrong and he is right? No.

The approach with knack recognizes that the mother’s forgetfulness and confusion created the situation. It is sensitive and understanding for the son to apologize, even when, in fact, he is right and she is wrong!

Repetition

Even when the person has just eaten, he or she may have forgotten or be fixated on food: “When is lunch? When is lunch? Let’s eat.”

No-Knack Approach

“How many times do I have to tell you that we just had lunch? Please be quiet, you’re driving me crazy! You just go on and on and on!”

Caregiving with Knack

“Sis, we’ll have a meal soon. Here’s a piece of fruit to tide you over.”

OR

“Sis, let’s put on some of that New Orleans jazz music we love so much and see who can still dance the best. Do you remember our first double date?”

Why It Works

The no-knack approach fails because being reprimanded can make the person defensive, even angry, and does little to end the repetition.

The approach with knack (“We’ll have a meal soon”) validates her question. The sister’s offer to put on old music and her question about their first double date are wonderful distractions that, it is hoped, will break the pattern of repetitive questions.

Dilemmas with Driving

A caregiving family is terribly upset and concerned that Father refuses to give up driving, despite his recent diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease.

No-Knack Approach

“Dad, we followed you around town. You’re a terrible driver. You’ve got Alzheimer’s, and you’re going to kill someone.”

Caregiving with Knack

(Encouraging a doctor to report Dad’s condition to the Department of Motor Vehicles [DMV] and then learning that he has failed a written and driving test.) “Dad, I can’t believe they’ve cancelled your license. We’ll look into this, but you can’t drive without a license! Let’s see about retaking that driving test in a few weeks.”

Why It Works

The no-knack approach could turn the person against you, will probably not change his desire to drive, and is overly confrontational. Often, the more you push as a care partner, the more the person pushes back! The approach with knack allows someone else to become the bad guy—the doctor, the insurance company, or the DMV. Care partners have also employed other tricks such as disabling the car or lending it to a relative.

CONCLUSION

Even care partners with knack don’t get it right all the time. The nature of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia is such that there are always good and bad days (for the person with dementia and for the care partners). An activity or approach may work wonders one day and fail the next. Yet care partners with knack are always willing to try something different and adapt, knowing that approaching problems with knack will never make matters worse. Knack helps you make the best of any situation.

Consider this case of a certified nursing assistant (CNA) at Karrington Cottages in Rochester, Minnesota:

The CNA accompanied a resident with dementia to her room to help her get ready for bed. As they walked to the resident’s room, the woman insisted that she wanted to help the CNA get to bed. She said she had to do this before she could go to bed herself. Thinking on her feet, the CNA went to an empty room, slid under the covers of the bed, and allowed the resident to tuck her in for the night. The person then went to her own room, and another staff member helped her get to bed. Here the CNA let the resident recall the comforts of home and a time when she tucked in her own children. It was caregiving with knack.

Best Friends Pointers

- Using elements of the knack are a key part of the Best Friends approach and will help you enjoy more success in navigating the challenges of dementia.

- Don’t despair if the knack doesn’t come easily for you. Keep working at it and you will develop more knack every day.

- People with knack employ common sense and strive to keep their sense of humor. Trust your instincts, take one day at a time, and try to keep laughter in your life even on those tough days.

- Having the knack of good care is not just about kindness; it provides tools to turn the “no” into a “yes,” make personal care easier, and build a more successful relationship with the person.