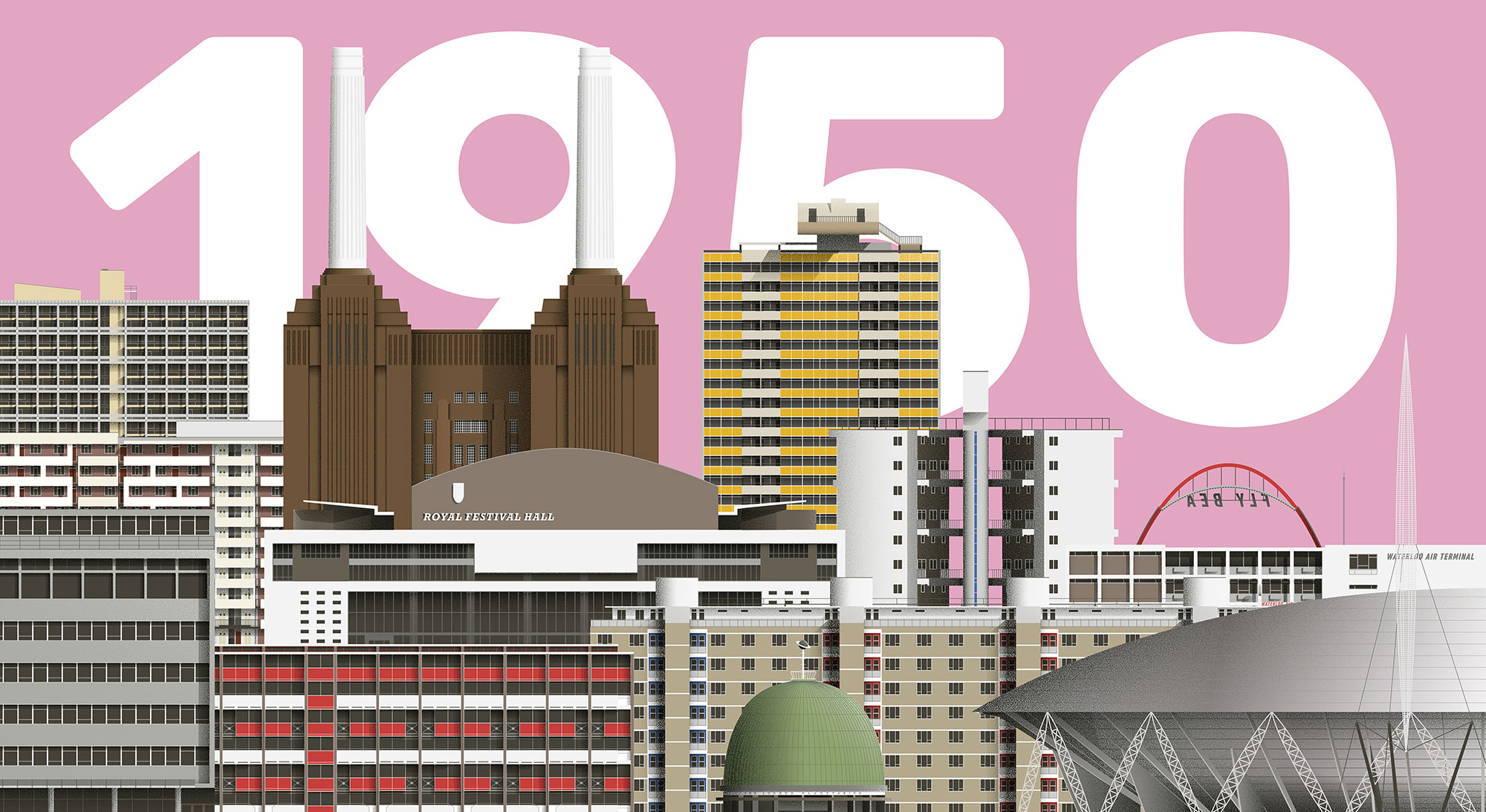

As the 1940s roll into the 1950s, London remains blighted by the cost of war – the city is drab, run down and in many areas empty. But its luck is set to change. With the factories free to return to their stated purpose, they are producing more and more goods; reconstruction is in full swing; and the docks are shipping record quantities of goods for export. To top if off, the government has had a brilliant idea, designed to boost the nation’s confidence – a huge festival showcasing Britain’s grand achievements in science, technology and industrial design. Enter, the Festival of Britain.

The South Bank – a derelict industrial zone - was chosen as the main site for the extravaganza named the Festival of Britain. Most of the architects and designers behind the festival were very young, in their twenties and thirties. Their bold and progressive visions were realised in the festival’s twenty-seven pavilions. The fair was a revolution not only in design, but also in materials and technology. A mix of aluminium, plastic, concrete and glass shaped the buildings and influenced British architecture for years to come. The planning of the festival started in 1947 and the event ran from May to September 1951. The primary audience was the UK itself, however the event was advertised in thirty-four different countries abroad. London Transport sent four double-decker buses with built-in exhibitions on a tour around Europe to attract potential visitors.

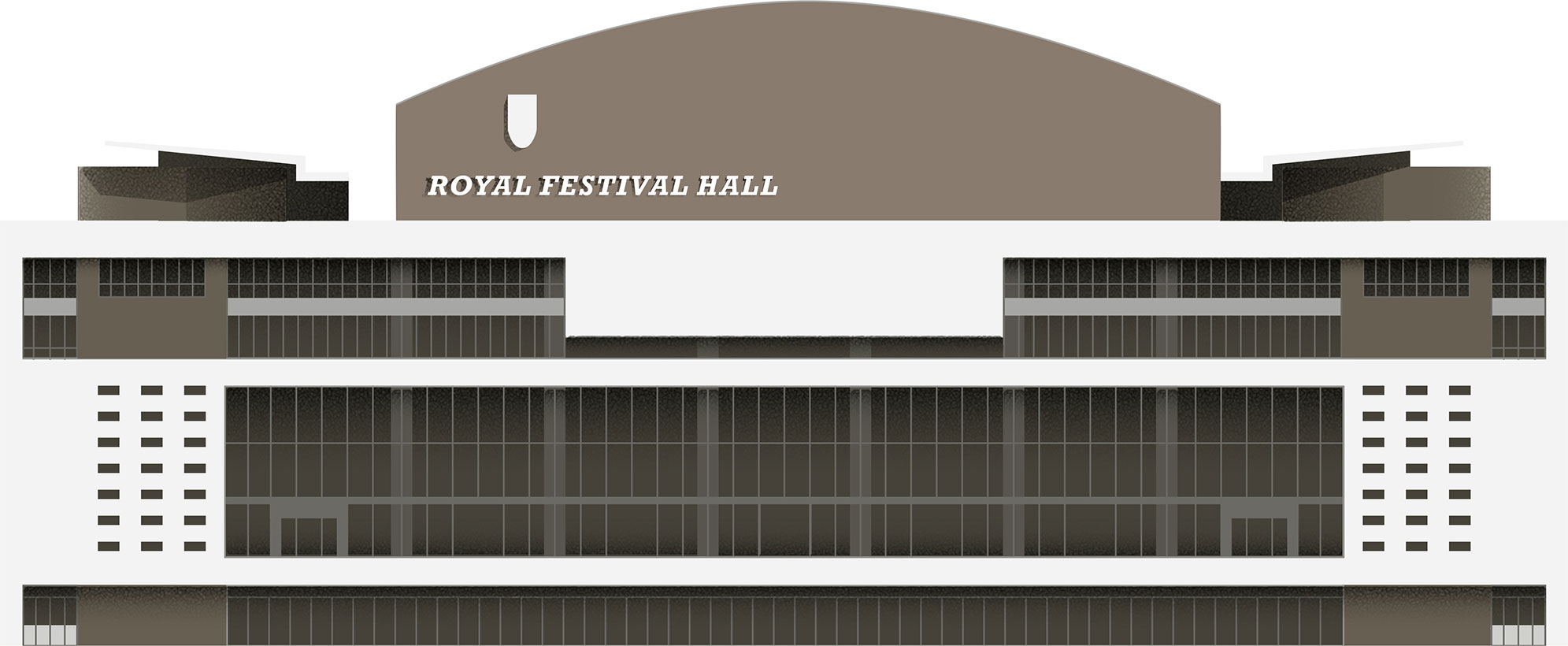

The Royal Festival Hall (036) was built as the centrepiece of the festival and is the only surviving festival structure on the South Bank. Constructed from the best available materials, it was also a replacement for London’s greatest concert auditorium, Queen’s Hall, which was lost in the Blitz. Noise and vibrations from a nearby railway bridge were dealt with using an innovative approach known as the ‘egg in a box’. The auditorium is suspended in the centre of the building and the surrounding space cancels out the unwanted noise. During construction, the site was visited by modernist legends such as Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer and Frank Lloyd Wright, who had nothing but praise for it.

036 Royal Festival Hall

Robert Matthew, Leslie Martin, Pete Moro

1951

1951  SE1 8XX

SE1 8XX

English architect Ralph Tubbs, who was Ernő Goldfinger’s unpaid intern before the war, was only in his thirties when he designed the Dome of Discovery (037). The festival’s largest and most futuristic building had a sleek silhouette, reminiscent of a flying saucer. It was the largest aluminium structure in the world and a symbol of the optimism of Tubbs’ generation. Inside was a huge scientific exhibition, showcasing the feats of British innovation, including radar, jet engines, nuclear power stations and penicillin. What’s more, you could send a signal to the moon via a satellite dish installed on top of a ‘Shot tower’ on site.

037 Dome of Discovery

Ralph Tubbs

1951

1951  1952

1952  SE1 9PX

SE1 9PX

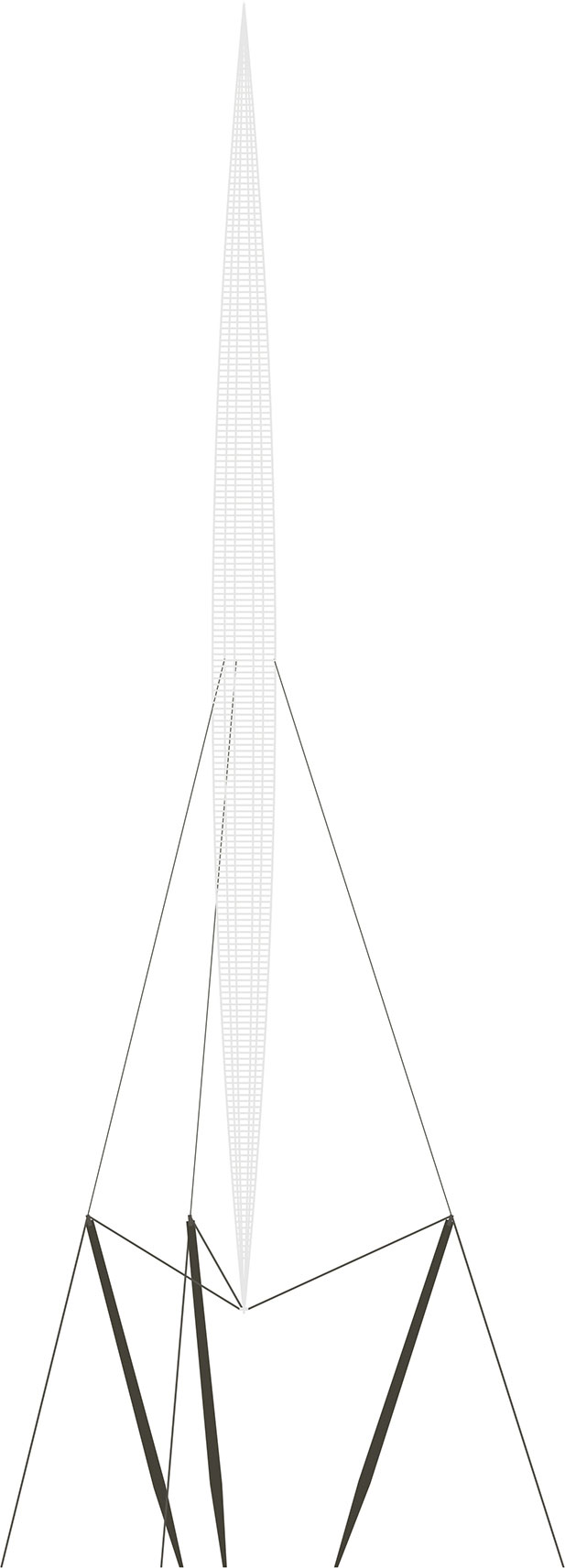

A competition for a structure that would attract attention from north of the river was won by American-born Hidalgo Moya and Englishman Philip Powell, both in their twenties. They teamed up with Austrian structural engineer Felix Samuely to build a gravity-defying steel structure called Skylon (038). Shaped like a cigar and supported only by thin steel cables, the (seemingly) levitating structure was just a couple of metres shorter than Big Ben. Visitors joked that Skylon was similar to the British economy – it had no visible means of support. The Dome of Discovery and Skylon inspired Richard Rogers when designing the Millennium Dome (100) at Greenwich Peninsula half a century later.

038 Skylon

Hidalgo Moya, Philip Powell & Felix Samuely

1951

1951  1952

1952  SE1 9PX

SE1 9PX

After just four months, the gates of the festival site closed. The Festival of Britain was a huge success – 8.5 million visitors came. It changed British architecture, art and crafts for decades to come. It was also a place of fun and education for the working and middle classes from all over. But people on the political right saw this through a very different prism. Churchill hated the idea and called it ‘three-dimensional Socialist propaganda’. Sure enough, when he won the general election that autumn, his first act as a prime minister was to order the clearing of the site. Most of the pavilions were only temporary anyway, but even the popular Dome of Discovery and Skylon were sold for scrap metal.

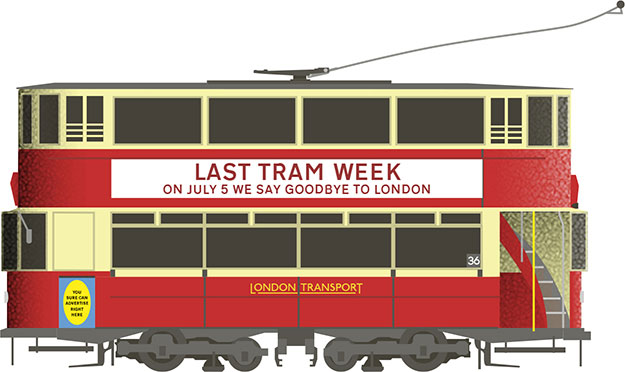

Indeed, streets were changing fast. The system of electric tramways was thought to be too inflexible and outdated. Instead of investing in their improvement, it proved cheaper to replace them with new diesel buses. On 2 July 1952, the last tram retired to its depot. Even with the trams out of the picture, electricity consumption rose, and numerous coal-fired power stations filled the air with smoke. The coal fired in the power stations and in homes was low grade, because most of the better quality coal was exported abroad, to supply much needed cash.

That winter, the smoke, combined with diesel emissions and thick fog (due to an absence of wind), caused chaos in the streets. Visibility was so bad that even cinemas had to close because people couldn’t see the screen. All public transport apart from the Underground network came to a halt, as did the ambulance service. The Great Smog lasted less than a week but it resulted in as many as 12,000 deaths in London, largely from bronchitis and pneumonia.

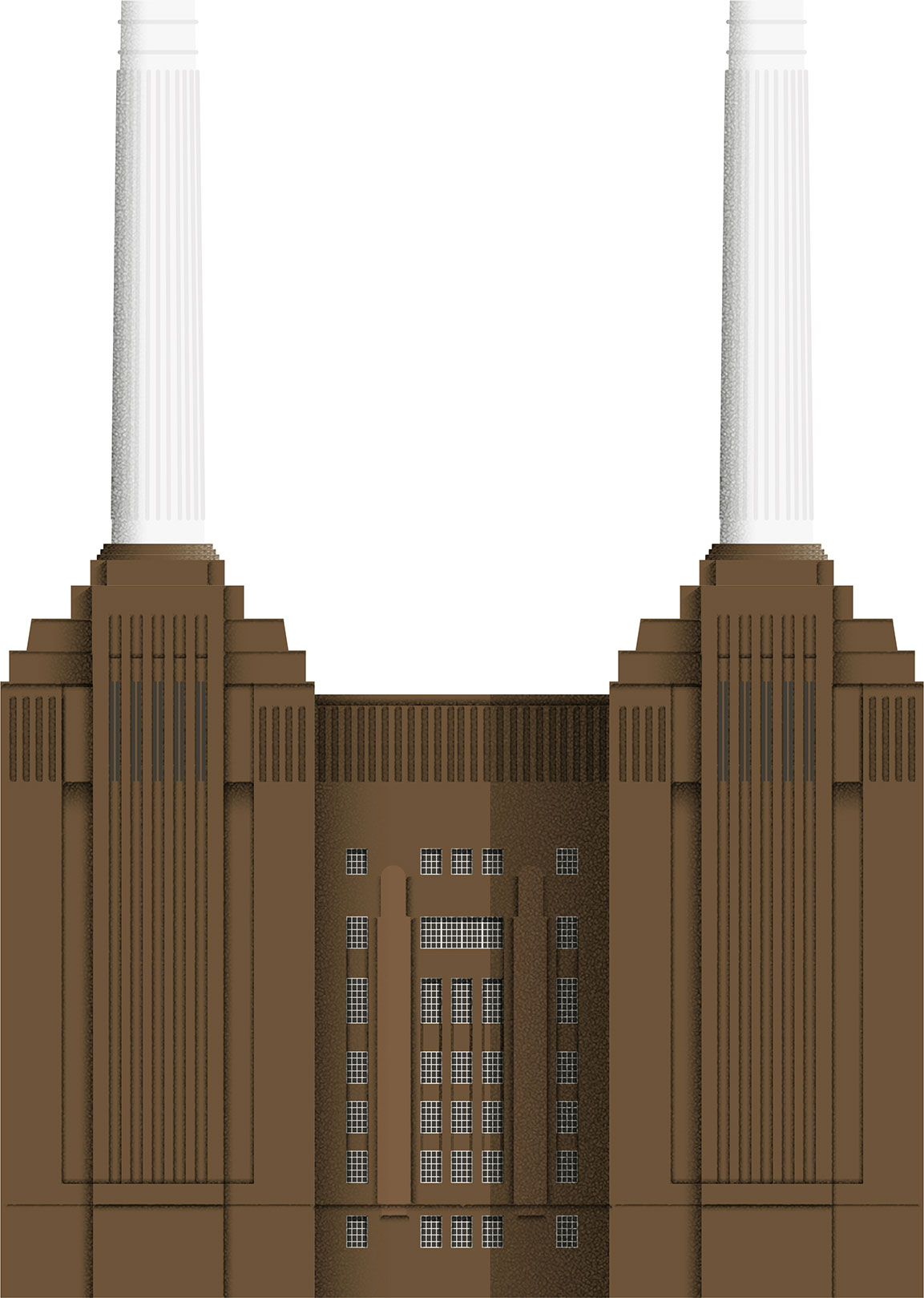

One of the buildings blamed for the Great Smog was Battersea Power Station (039). Although it started producing electricity in 1933, its fourth and last chimney was finished some twenty years later. Its brickwork was designed by English architect and designer Giles Gilbert Scott, who was known for combining gothic and modern architecture. The multi-disciplinary designer was also responsible for Liverpool Cathedral and the iconic red telephone box.

039 Battersea Power Station

Giles Gilbert Scott

1955

1955  SW8 5BN

SW8 5BN

The power station was, at the time, the largest brick building in the world. An experimental system was used to reduce sulphur emissions. It effectively ‘washed’ the smoke, but the truth is it worsened the situation. The by-product released into the River Thames was extremely toxic and the practice had to be stopped in the 1960s. The station ceased to operate in 1983, and after decades of decay is now being redeveloped into luxury flats, offices and shopping spaces.

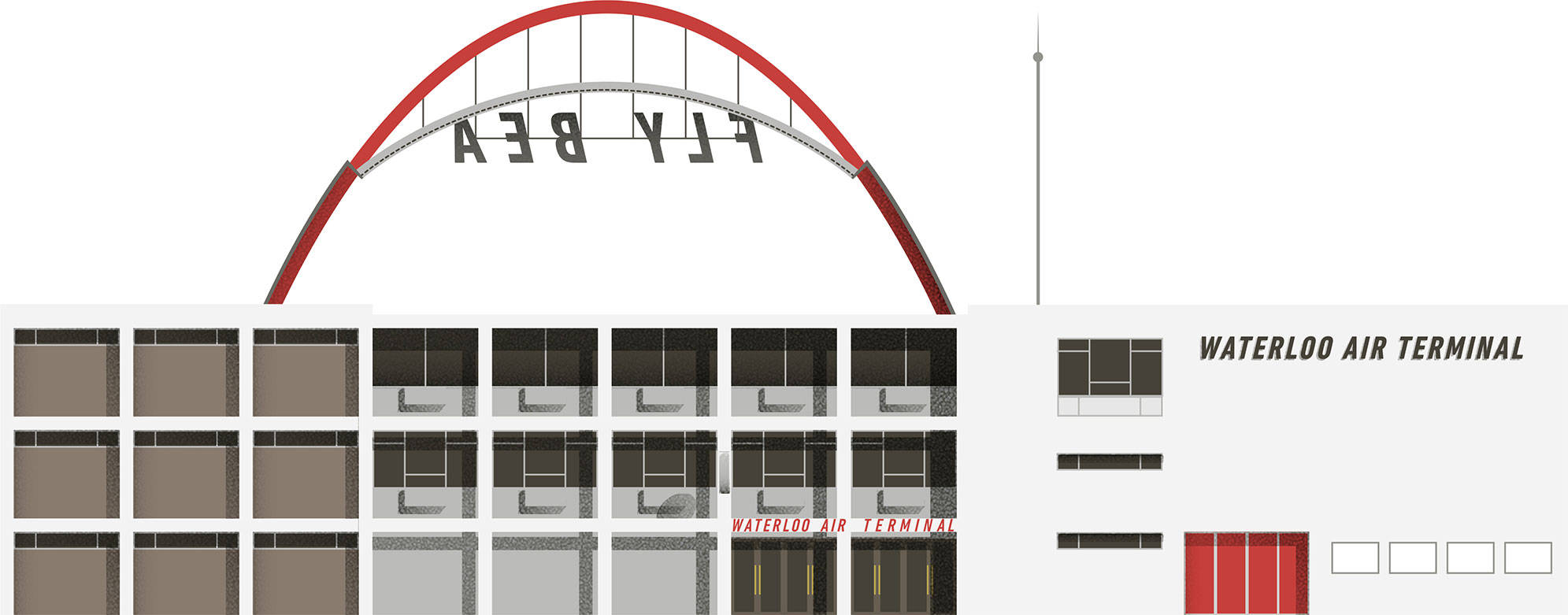

The 1950s saw air travel become a habit for well-heeled Londoners. London (later Heathrow) Airport didn’t have the best transport links yet and so the Waterloo Air Terminal (040) was used as a check-in facility. The terminal was inside the modified Station Gate building, still standing after the Festival of Britain, where it had served as an entrance to the festival area and Underground station below. Impressive laminated arches were made from timber donated by the Canadian Lumbermen’s Association.

040 Waterloo Air Terminal

John Burnet, Tait and Partners

1953

1953  1957

1957  SE1 7NJ

SE1 7NJ

The repurposed building was used by British European Airways and other European airlines between 1953 and 1957. A heliport behind the building saw some lucky passengers using helicopters as the fastest way to the airport, but most of them travelled on a fleet of buses.

Festival Star

The Festival of Britain logo was created by Abram Games, one of the greatest British graphic designers of the twentieth century. It appeared on everything from printed materials to vehicles and buildings.

Westland Whirlwind

The helicopter service between the terminal at South Bank and London Airport ran seven times a day. Many people used the seventeen-minute journey as a sightseeing flight. Floats were added in case of an emergency landing on the River Thames.

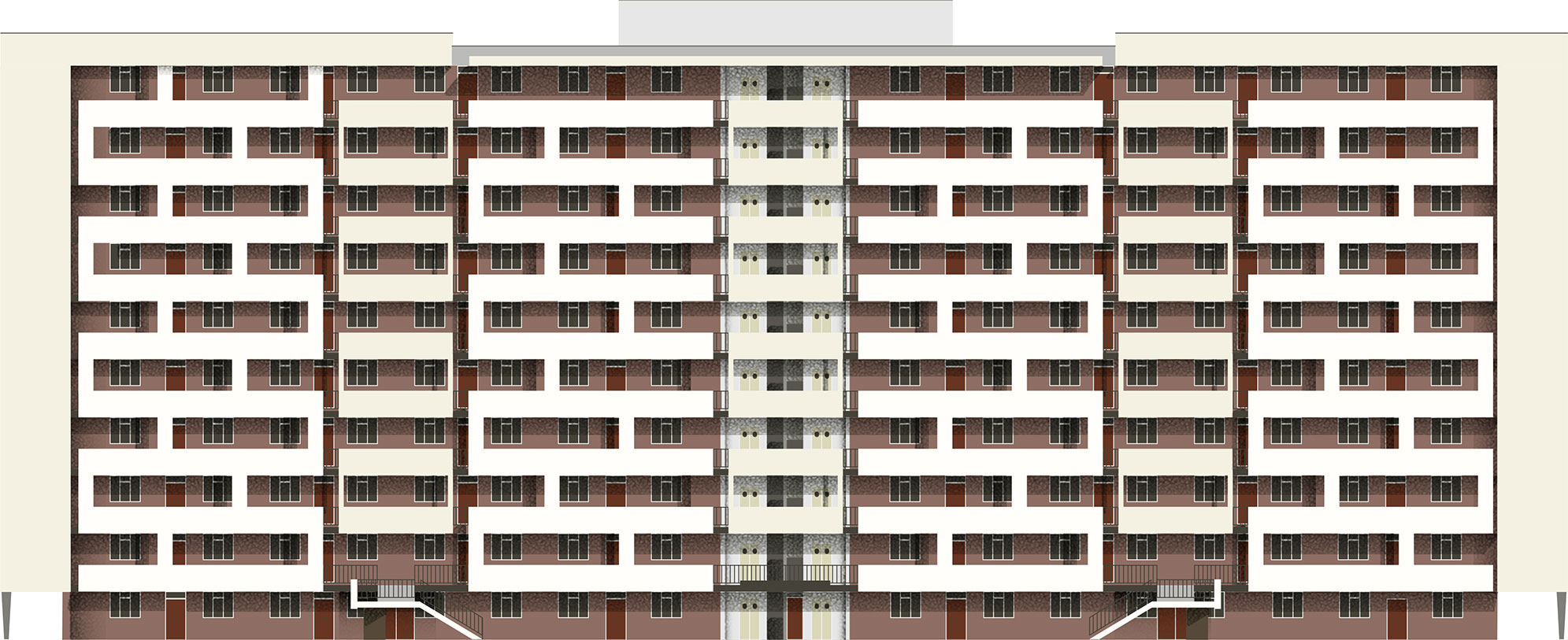

New housing was a top priority for local councils during this period. One large area in Bayswater, which was previously occupied by rows of terraced houses and made vacant by bombs and a V1, became Hallfield Estate (041). A competition for the design was won by Tecton, led by Berthold Lubetkin. But before the construction started, the practice fell apart. Lubetkin, disillusioned after clashing with authorities on other projects, retreated to his isolated farm in Gloucestershire, where he took up farming. He still practised architecture, although in limited form.

041 Hallfield Estate

Denys Lasdun, Berthold Lubetkin, Lindsay Drake

1958

1958  W2 6EL

W2 6EL

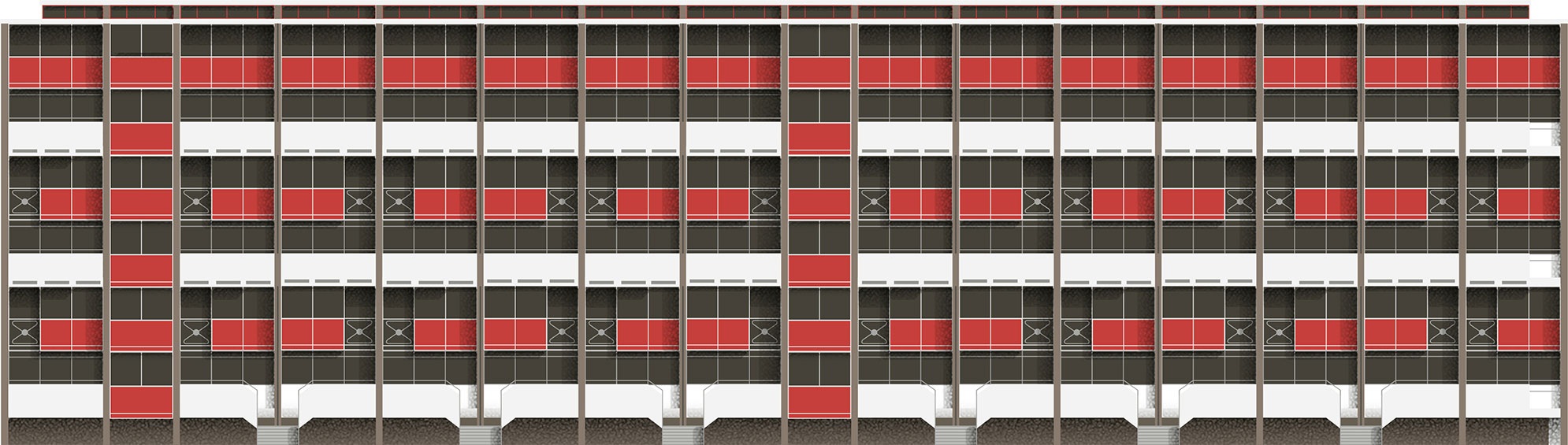

The estate was eventually realised by two former members of Tecton — Denys Lasdun and Lindsay Drake. The original plan, devised right after the war when the housing crisis was at its most acute, had called for high density. But the plan was revisited and the density lowered by the removal of the top floors, and two of the blocks entirely. The remaining fifteen blocks now range between ten and six storeys high. The pleasing pattern on the building’s façade is comprised of balconies, which also provide access to the flats.

AEC Regal IV 4RF4

British European Airways owned a fleet of sixty-five custom-built coaches. These one-and-a-half deckers had increased luggage capacity. They were replaced in the 1960s by the Routemaster buses, which towed luggage trolleys.

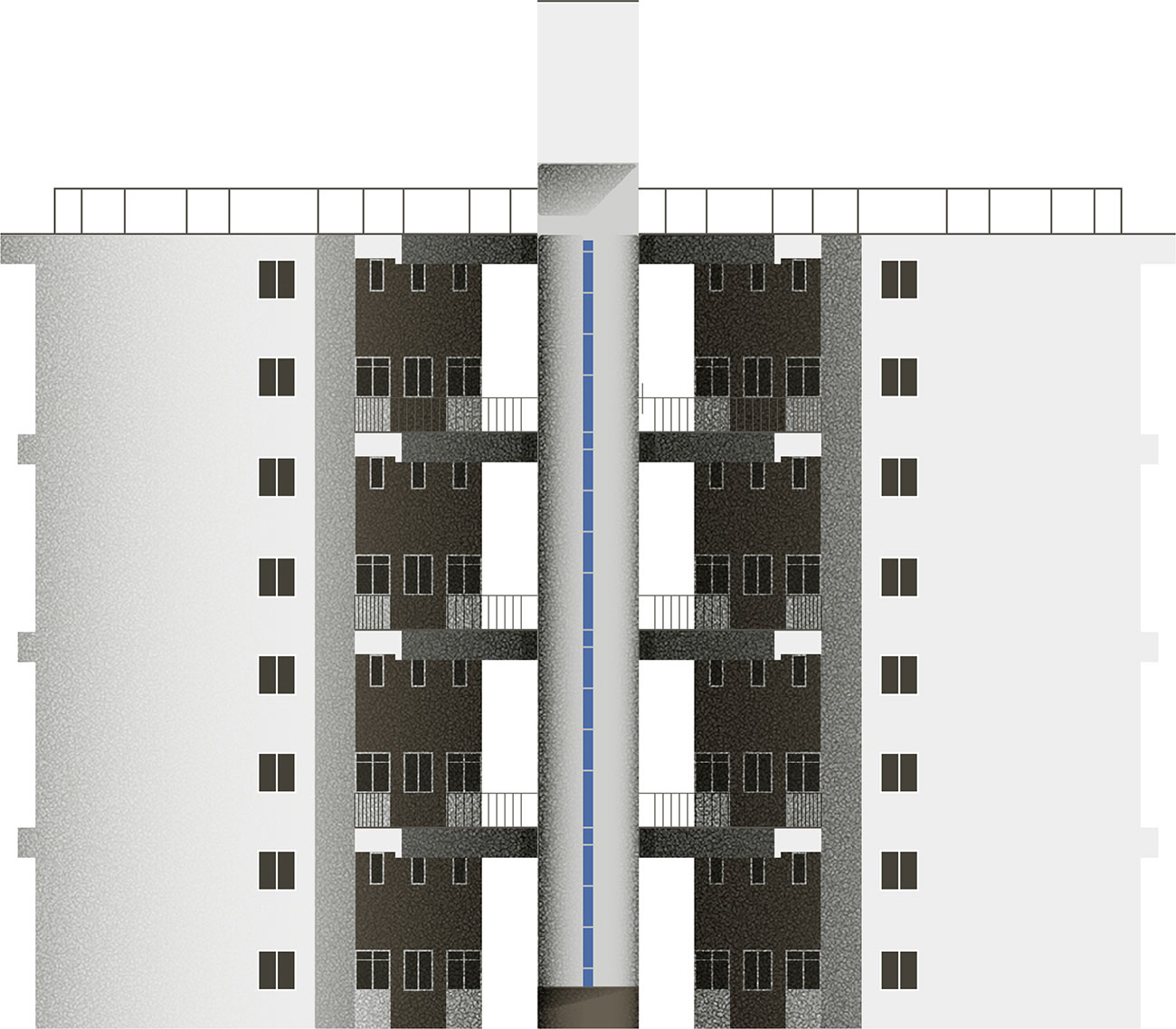

Completely different from most of the emerging housing projects was Sulkin House (042). Denys Lasdun was helping to realise Hallfield Estate, but he was also meeting residents of crowded terraces in east London to find out what they liked about them. Rather than being repaired, streets of Victorian terraces were razed to make space for new development. Lasdun designed an eight-storey building containing twenty-four maisonettes.

042 Sulkin House

Denys Lasdun

1958

1958  E2 6PG

E2 6PG

It is split into two residential blocks, connected by a separate core containing the stairwell and refuse chutes. This isolates the noise and allows more air and light into the building. Units face each other, to encourage neighbourly interaction. Lasdun, perhaps naively, hoped this would help recreate the life and relationships of the former East End streets. The architect built two more ‘cluster’ towers — Trevelyan House and Keeling House.

AEC RT ‘Bridge Jumper’ Bus

In 1952, the number 78 bus was crossing Tower Bridge when the bridge started to open. The quick-thinking driver accelerated and the bus flew over the enlarging gap. Passengers suffered only minor injuries.

Having suffered severe damage by fire bombs during the war, the City was an area of London in particular need of attention. In 1950, only 500 people still lived in the area. In an effort to boost residential numbers, local authorities organised a competition to design a new estate. Three teachers at Kingston Polytechnic – Indian-born Geoffry Powell, Londoner Peter Chamberlin and Swiss Christoph Bon – sent individual proposals, but agreed that if one of them won, they would form a studio together.

Powell (no relation to Skylon’s Philip Powell) won the competition and the famous practice of Chamberlin, Powell and Bon was born. Golden Lane Estate (043) was a council estate, built to house essential City workers at subsidised rents. Most of the flats were designed for singles and couples, as families were not a top priority here. The residents enjoyed great facilities, including a swimming pool, badminton courts, a bowling green, a nursery, a playground and workshops. Unusually for the time, the whole area was pedestrianised, with no access for cars.

043 Golden Lane Estate

Chamberlin, Powell and Bon

1956

1956  EC1Y 0TN

EC1Y 0TN

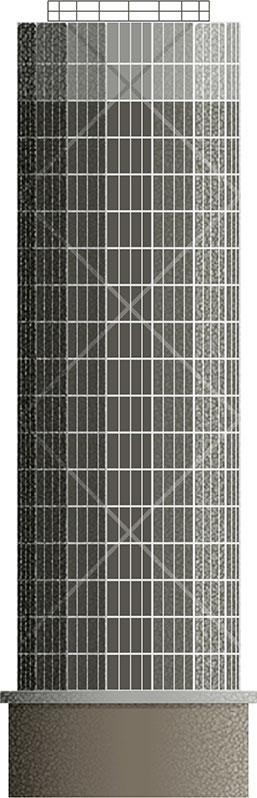

Golden Lane Estate was crowned by Great Arthur House (044). Fifty metres tall, with seventeen floors, it became the highest residential building in London. Its optimistic yellow façade teams up with the red and blue of the lower blocks. On the roof is a curvy concrete quiff, hiding inside it a lift and water machinery. Inspired by Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation, the three-level roof also had a pool, pergola and trees. However, following a suicide and vandalism, the roof has sadly been locked away.

044 Great Arthur House

Chamberlin, Powell and Bon

1957

1957  EC1Y 0RE

EC1Y 0RE

Morris J-Type Van

Replaced the last horse-drawn carts in London. It was a very popular delivery van in the 1950s, seen in the livery of the Royal Mail. The surviving cars now often serve as fashionable food trucks.

Some contemporary architects saw British post-war architecture as too ‘soft’, believing that it diluted the idea of modernism. Perhaps the best place to see the difference between both camps is Alton Estate in Roehampton. The earlier eastern side is mostly Scandinavian-inspired – a ‘soft’ combination of low-rise buildings and towers, designed by an architecture team led by Rosemary Stjernstedt from Birmingham, who spent six years working as a town planner in Sweden. But the west side of the estate is dramatically different.

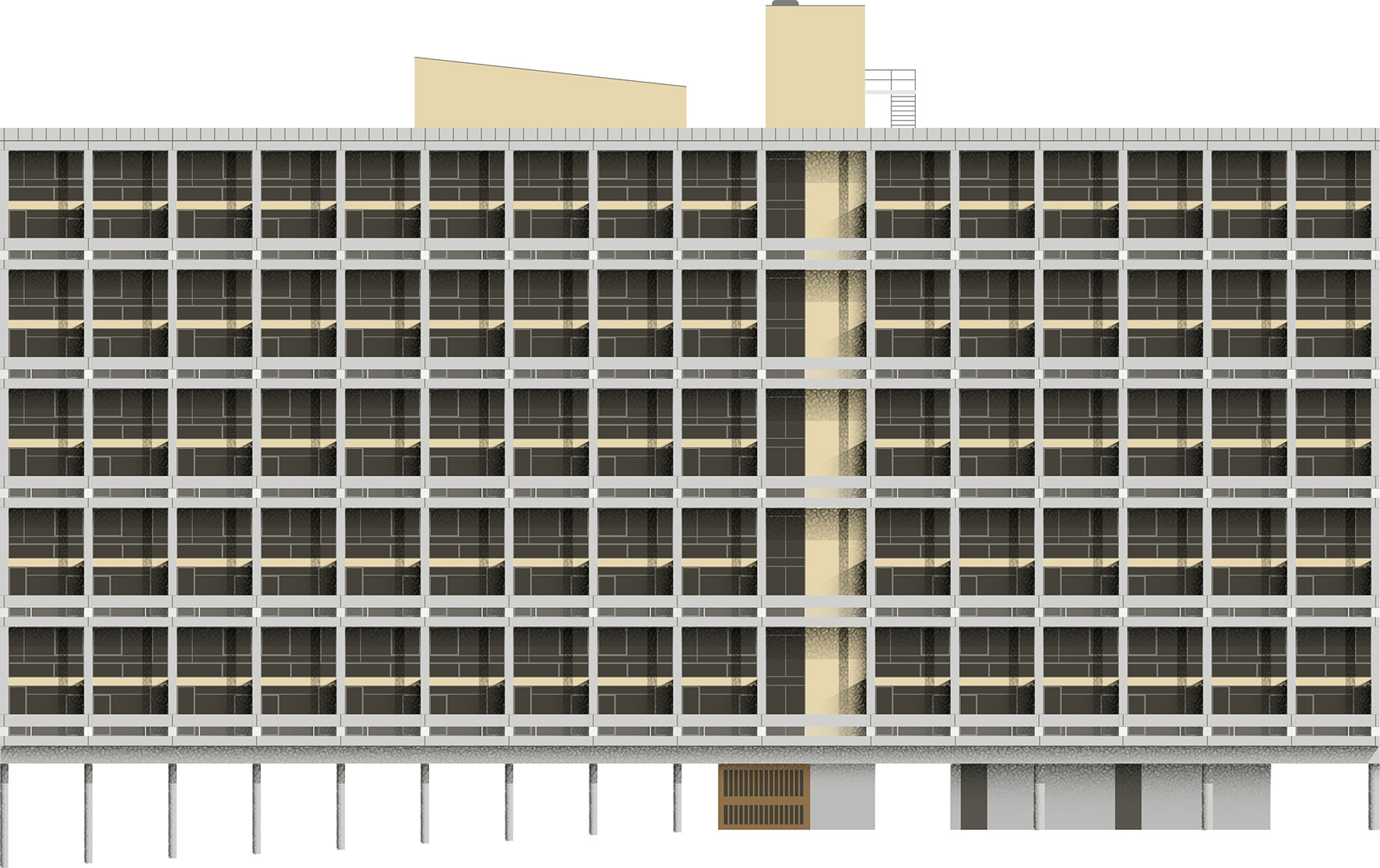

Five ultra-modern ‘slab’ blocks on The Highcliffe Drive (045) were designed by young progressive architects, and the influence of their visit to the recently finished Unité d’Habitation by Le Corbusier is clearly evident. Built on pilotis, it seems like the massive blocks are floating over the grassy slope. Inside, spacious two-floor maisonettes span the width of the building, allowing for windows on both the northern and southern sides. The buildings appeared in François Truffaut’s 1966 film adaptation of the dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451.

045 The Highcliffe Drive

LCC Architects’ Department led by Colin Lucas

1958

1958  SW15 4PX

SW15 4PX

The construction of these buildings coincided with an optimistic plan for rebuilding post-war London. Named after its author Patrick Abercrombie, the Abercrombie Plan was an attempt to change the whole fabric of London for the better. It proposed many changes, but the primary aim was to make London smaller and cleaner, and to move a portion of the population and some industry to New Towns built in the countryside. The reality proved more difficult and only fractions of the plan were realised.

The only estate built according to the Abercrombie Plan was Churchill Gardens Estate (046). Westminster Council selected a proposal by Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya, who were only in their mid-twenties. The large estate was built from 1946 to 1962 and replaced an area of Victorian terraces badly damaged during the Blitz. Uniquely, the estate had a district heating system – the first of its kind in Britain. A clever system collected surplus heat from Battersea Power Station via a tunnel under the River Thames.

046 Churchill Gardens Estate

Powell and Moya Architect Practice

1951

1951  SW1V 3HU

SW1V 3HU

A glazed accumulator tower, also designed by Powell and Moya, distributed heat around the estate. The site contains thirty-two blocks ranging from three to eleven storeys high, and housing some 5,000 residents. Efforts to accommodate a balanced cross-section of society were largely successful. Residents of the elite (and expensive) Dolphin Square soon complained about their flats not being as nice as the ones on the council estate across the road.

Accumulator tower at Churchill Gardens Estate

The post-war decade also saw a change in the demands and rights of London’s workers. New power gained by trade unions materialised in the construction of Congress House (047). It opened in 1958, ten years after English architect David du Roi Aberdeen won the competition. The façade is clad in grey polished granite. Unusually, the main assembly hall is in the basement and receives natural light through an inner courtyard, which serves as a light well.

047 Congress House

David du Roi Aberdeen

1958

1958  WC1B 3LS

WC1B 3LS

Sitting over the glass ceiling is a sculpture by Jacob Epstein, carved on the spot from a single ten-ton stone. Most of the ground floor is open, broken only by columns. Impressive curved glass, covering the circular staircase leading to the basement, breaks the grid system. The building was a reflection of the strength of the trade unions during this period. Over the next few decades, their influence diminished.

LCC E/1 Tramway

These tram cars were introduced in London in 1910 and served for an incredible forty-two years. The last week of their service in 1952 saw emotional goodbyes and overcrowded cars as people scrambled for one last ride.

During the 1950s, tensions between the West and the Soviet Union culminated in Cold War. Britain’s role as a global super power was superseded by that of the Soviet Union and the US, and the two became determined to prove the other less advanced. On 4 October 1957, a small metal ball named Sputnik left Earth and circulated the globe while emitting a beeping sound. Radio amateurs from around the world tuned in. The Americans were shocked, and soon committed their best brains and huge sums of money to outstripping the Soviets. The space race was on. Meanwhile, Britain opted for a more down- to-earth approach – in 1958 the London Planetarium (048) opened on Baker Street.

048 London Planetarium

G. Watt

1958

1958  NW1 5LR

NW1 5LR

It was the first planetarium in the Commonwealth, and unlike most at the time, it was a commercial gig rather than a government-backed university project. As the only planetarium in London, it drew in huge crowds, including many London schoolchildren. But in 2006, after years of declining visitor numbers, the planetarium ceased astronomical projections. Renamed the Stardome, visitors were instead treated to a 360-degree cartoon film about celebrity (the result of a business partnership with Madame Tussauds). The Wonderful World of Stars received a cold reception from astronomy fans. Luckily, the Peter Harrison Planetarium opened at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich only a year later.

AEC Routemaster

Without a doubt the most famous of all London buses. It was operated by a driver and a conductor, who stood on the open boarding platform at the back. The (relatively) reliable buses served on London streets for an unbelievable forty-nine years.

Austin FX4

The iconic taxi was launched in 1958 and stayed in production for an incredible forty years until 1998. This was largely because there wasn’t enough money to develop a new design to replace it.