4

Species

Men … begin, like every animal, by eating, drinking, … by … actively behaving … satisfying their needs. Start, then, with production.

—Karl Marx

Now we have a holism we can live with, an implosive, subscendent holism. Utilitarian holism, the holism of populations, is explosive—the whole is especially different (better or worse) than the part. There is no such thing as society! Or, specific people don’t matter! Utilitarian holism sets up a zero-sum game between the actually existing lifeform and the population. One consequence is the trolley problem: it is better to kill one person tied to the tracks by diverting the trolley than it is to kill hundreds of people on the trolley who will go off a cliff if we don’t divert the trolley. There’s the left-wing variant: talk of wholes is necessarily violent (racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic and so on) because what exists are highly differentiated beings that are radically incommensurable. In this leftist thought mode, there’s as little chance of imagining you’re a member of a group as in neoliberal ideology!

Gaian holism, the current ecological-political holism, also sets up a zero-sum game. An actually existing lifeform is a replaceable component. There is the right-wing version of this, often called Mother Nature. How dare we assume that we humans are more powerful than Mother Nature! If the Earth warms, Mother Nature will just replace her extinct parts. Then we have the correlationist versions of explosive holism. The Decider acts like population or Gaia, in a decidedly religious key. History, or progress, or destiny, gets to decide what’s real. I had to run over you with this tank, it’s the march of history. I may feel personally upset, but don’t blame me, I’m just carrying out God’s will.

As it approaches these sorts of whole, leftist thought rightly cringes. So ironically, it leaves out the one thing that could help it to think group political action!

Luckily, we’ve decided to be holists but to reject the explosive concept of the whole. Wholes are heaps whose members are uncountably undecidable. But they exist. A football team exists in the same way as a football player because it has a difference between what it is and how it appears: it might wear different uniforms at different matches. A whole is one, its members are more than one, so the whole is always less than the sum of its parts.

Species subscends me. Humankind exists, and I am a member of humankind. But there is so much more to me than being a member of humankind. So it’s perfectly possible for us to achieve solidarity with nonhumans: I am not bound in an impervious whole and there are parts of me that also belong to other lifeforms, are common to them, or just are other lifeforms. We discover this solidarity down below the anthropocentric, murderous-suicidal idea of who we are. We are clouds, not metaphysically solid. You can’t point to us directly, but we still exist. We are just as “poor in world” as the nonhuman beings that Heidegger labels that way, because “world” subscends its world parts. Being poor in world is what having a world means. There is no grand destiny to fulfill, thank goodness. The imperial anthropocentric project—a project with human as well as nonhuman victims—is over, because we can’t think it anymore with a straight face.

To achieve non-racist, non-speciesist species, we need to allow heaps to exist. Vanilla logic doesn’t allow for the possibility of heaps. If I have a heap, say a pile of sand, I can remove parts of it and still have the heap, and the same logic will apply until I only have one part left. So, there can’t really be heaps. Or, I can add a grain of sand to another one, and there isn’t a heap, and keep on going until I have tens of thousands of grains, and there still isn’t a heap so there are really no heaps. Imagine an ecosystem, which is a heap of lifeforms. I can take the lifeforms away until there’s nothing there, yet this paradoxical heap logic will still apply so that ecosystems can’t really exist. Great! Let’s build a mall! Fuck ecology! It doesn’t make sense.

Humankind is a heap. If you care about ecology, you care about heaps, because lifeforms are heaps, and ecosystems are heaps. Heaps are paradoxical. Unless you allow for modal, paraconsistent and even dialetheic logics (that can say things are more or less true, or both true and false under some circumstances), you can’t allow ecological beings to exist. No one human is responsible for global warming. Her use of fossil fuels to start the engine of her car is statistically meaningless. But a heap of car-startings—say, all the ones she does in her life, and all the other car-starters on Earth—do cause global warming! And yet, if we take one car-starting away, there is still a heap that causes global warming—and we can continue until there’s just one key turning in one ignition, and the same logic applies. So, nothing causes global warming. To allow ecological beings such as ecosystems and global warming and humans and DNA to exist, we need to allow heaps to exist, and we need to allow heaps to be radically different from their members. Radically different.

There is a subscendent gap between humankind and its members. This means that for humankind to exist, sets that contain members that aren’t strictly members of those sets must exist. We will upset Bertrand Russell, but we will have Cantor, Gödel and Turing cheering us on. Now we also know that ecological action only takes place at the heap level. Destroying or “saving” Earth is a matter of collectives.

What about all the species, the biosphere—the heap of heaps? The same logic works here. If we remove a heap, the heap of heaps is still a heap. So, heaps aren’t real, and it doesn’t matter that lifeforms go extinct—if we cling to a rigid true–false distinction and if truth means not contradicting yourself. So, the entire thing is also subscendent and is therefore vague and fuzzy. But this is great because it means that heaps can combine. I can be a member of one heap and a member of another heap at the same time. More than combining, heaps can overlap. There is no top level, no one heap to rule them all, so we have lost the idea of a one-size-fits-all political or economic structure. Communism cannot come in a one-communism-to-rule-them-all form, for instance, an official version imposed by the state. But we have gained the idea that heaps can be shared, which means that species can be symbiotic, which means that it’s part of being a species to be able to have solidarity with other species. And because of the subscendent gap between a heap and its members, ecological action must be collective, so we can let our individual selves off the hook and stop preaching at each other.

HUMANS WITHOUT HUMANITY

So, it’s perfectly possible to talk about species without resorting to universalist language that deletes, for instance, the obvious uneven distribution of responsibility for global warming.1 We don’t have to stay at the level of specific human groups, populations or cultures. We can talk about ourselves at a larger space-time scale, without compromising our politics. The Left had better be able to talk about humankind, because if we don’t, we will have ceded that level of discussion to BP and Silicon Valley.

Subscendence is the half-sister of transcendence, which has to do with gaps between things and how they appear, gaps that can’t be pointed out in ontic space-time. Whereas immanence, which is a very popular way of talking in an ecological way, eliminates these gaps. But if there is no difference between a polar bear and a polar bear appearance, then when the polar bear goes extinct, there is no problem. In fact, extinction doesn’t really happen. Whereas, in a world of subscendence, extinction happens and I can think it, but I can’t know it or see it or touch it. Evolution, biosphere, global warming: all these are hyperobjects. They happen and I can think or compute them, and yet I can’t directly see them. Evolution and the biosphere are telling us something about polar bears. They are also subscendent.

A symbiotic community—we are all symbiotic communities—is a perfect example of a subscendent whole. (Indeed, it would be better to call it a “symbiotic collective” for that reason.) I am less than an individual qua human with “This is a human being” engraved on every single piece of me. I am a human insofar as I have bacteria and prostheses such as cows and fossil fuels. Nothing is like a stick of Brighton rock, a tube of mint-flavored candy, usually white inside and pink outside, with something like “A present from Brighton” inscribed in pink all the way through the tube, so that however much you suck on it, the writing remains. But this is not how things are. To exist is to subscend one’s parts. It’s not that I don’t exist, that my parts are more real than me. It’s that I faintly exist. Likewise, humankind exists faintly. Thus, we can know ourselves because we don’t set ourselves up as especially different, which would require another especially different being with whom to compare ourselves.2

One of the things disrupting our human world is … humankind.

Now we have a way to think what the myth of Adam Kadmon and Hobbes’s Leviathan imagine in an explosive holist way: a body consisting of many bodies. Hobbes’s support for monarchy arises from the explosive holism with which the whole is thought. But now we can think the body of humankind in an implosive way. A collective, rather than a community, is a faint subscendent whole. Now we can think humankind beyond sentimental reductionism to an explosive whole: “We’re all in this together,” “We are the world.” Appeals to a universal humanity underlying appearances are politically dangerous.3 The collective powers of humankind have been displaced onto concepts such as God, as Feuerbach argued, but also onto concepts such as Man and Humanity. The explosive concept of the human is a form of alienation.

A racist or a speciesist is someone who believes that one can point to species in ontic space-time. A subscendent humankind contains by contrast an irreducible gap between itself and little me. Species is spectral, and the human is a near-at-hand example of this spectrality. Communism is a specter not only because it frightens the capitalists, but also because it involves spectral beings who do and do not coincide with themselves at every point. It involves specters by allowing their full spectrality to manifest.

DOWN WITH NATURE, DOWN WITH ARTIFICE

Thinking this way about species permits us to resolve a debate within Marxist ideology theory, concerning whether or not there is such a thing as “human nature,” the debate between Althusserians and non-Althusserians. Althusserians argue that there was an epistemological break between pre-Capital Marx and the Marx of Capital onward. The break consisted in dropping the idea of an essence from which humans have become alienated. The Althusserian view is that this very idea, that humans are separate in some sense from their contextual, economic enjoyment mode, is an expression of ideological alienation.

Let’s summarize what I’m about to say in brief, and a bit schematically. Marx’s non-Althusserian, pre-Capital alienation theory of ideology is right, but for the wrong reasons. And that’s because there is indeed something that escapes the clutches of ideology, not because there’s an intrinsic vanilla continuous substantial Nature underneath appearances—the Aristotelian essentialist version that the cool kids are right to be suspicious of—but because of OOO object withdrawal. And this in turn means that the stuff that differs from its appearance isn’t just the human being, but also the brick, the Jim Henson puppet, Frank Oz’s voice, goldfish and black Audis. Furthermore, the Althusserian theory—the post-“epistemological break” Marx of Capital who holds that ideology is all pervasive and has no outside, and so forth—is wrong, for the right reasons. Once again: good old alienation theory is right for the wrong reasons, and the cool kids’ theory is wrong for the right reasons. The latter is the case, because it’s true that you can’t access the outside of your access mode, by definition; yet this doesn’t mean that access modes and data are all there is. OOO is capable of resolving a decades-long, very technical debate within Marxist theory. Now let’s go through this in greater detail.

The content of the non-Althusserian view is correct, but not for the stated reasons, in such a way that the format of the Althusserian view is wrong, but for the right reasons! What humans have become alienated from is humankind, an implosive whole that is a part of a similarly subscendent symbiotic real. But the way explosive holism expresses the belief that human being is a substance that underlies economic relations is itself a form of alienation.

The split between the Althusserian and non-Althusserian views maps onto the agrilogistic ontological split between appearing and being. For example, we might argue that alienation means that there is some original essence that is deprived of its full expression in capitalism. There is some constantly present substance that gets parceled out, frozen, segmented, diverted, reformatted. Underneath appearances, which for Marxism means underneath (human) economic relations, the song remains the same. This is commonly held to be the view of the early Marx. One argument for it is that if there is nothing underneath, how come we feel such suffering in capitalism?4

Such an argument raises an immediate objection: it’s superimposing something we can feel on top of something structural. It doesn’t matter whether we can feel alienated or not: we just are alienated, and feeling alienated isn’t what alienation means. So, a variant of the non-Althusserian position is that humans are prevented from the full exercise of their productive powers; within capitalism only a limited range of pleasure modes are available, no matter how wide-ranging they seem. This is closer to what Marx means by species-being, which has to do with production or creativity. Production isn’t about working on sheet metal in a factory, necessarily. Production is the pleasure of biting into a fresh juicy peach:

Men do not by any means begin by “finding themselves in this theoretical relationship to the things of the outside world.” They begin, like every animal, by eating, drinking, etc., that is not by “finding themselves” in a relationship, but actively behaving, availing themselves of certain things of the outside world by action, and thus satisfying their needs. Start, then, with production.5

Notice that Marx uses the word “behave,” the word we associate with bees executing algorithms and not with humans “acting.”

Then there is the Althusserian view on the epistemological break between the early and the later Marx. The Marx of Capital and on isn’t concerned with some original essence: there is none. Everything is produced (in the last instance), by (human) economic relations. The very idea that there is some original essence that has been betrayed is precisely the ideological form that alienation takes within capitalism. The idea that I am free to choose what I believe, as I feel free to choose my shampoo in a supermarket, is precisely ideology. The essence is a side-effect or byproduct of the enframing of reality by a certain mode of (human) economic relations.

Both the extreme correlationist and the vanilla essentialist arguments are holding two pieces of the Kantian puzzle, the thing in itself and how that thing appears. For the vanilla essentialist, the trouble has to do with how appearances are superficial, that there is an underlying essence that is unaffected by capital, and therefore alienated to the extent that it can’t find expression. We are wage slaves who upon liberation will be fully ourselves, no longer slaves. We will be de-objectified. Liberation strips away false appearances.

For the correlationist essentialist, the picture is quite different. What is constantly present are (human) economic relations. The idea that there is a difference between real us and commodified us is the illusion. Liberation means that this illusion collapses. So, what remains is the freedom to posit whatever type of reality we want. Liberation strips away false reality.

Acknowledging humankind suggests another solution. We aren’t totally caught in ideology, not because there is an underlying nature that is constantly present, but because of object withdrawal—because we are spectral beings. Yet in turn this means that interpellation is a deep feature of how things are. We are not capable of venturing outside of our access modes. We are shrink-wrapped in them, so that we anthropomorphize everything. But that doesn’t mean that there’s no outside at all, or that we are caught forever within anthropocentrism.

There’s a big difference between saying that we anthropomorphize and that we are anthropocentric. Marx himself argues that we can’t help anthropomorphizing. That’s what species-being means. Things become realities for us when we bring them into economic relations. But this is not a prison without windows, because as I anthropomorphize this bunch of grapes, the grapes are grape-morphizing my fingers and my mouth, causing me to handle them just so. Anyone who has taken drugs will tell you that there is a more or less “right” way to handle them—one is drug-morphized. Everything is in the –morphizing business.

Let’s revisit the question of bees and architects, and the difficulties of distinguishing rigorously between algorithms and people. This difficulty gives rise to a spectral realm in which personhood becomes uncanny—it’s real in some sense yet we can’t point to it directly. The fundamental problem with dancing tables is that I can’t distinguish myself from one very rigorously, which doesn’t mean I’m a table, and doesn’t mean that the table is definitely a person. Science indicates that nonhumans might not simply execute algorithms. Ants hesitate—they circumspect when they climb up little ladders. Bees have mental maps to guide them home. Rats experience regret … The trouble is that this list of observations might be never-ending, since anthropocentrism could keep on refining what counts as a person so as to exclude any behavior of a nonhuman whatsoever—the tactic of proof-by-data invites this condescending delay.

We could, however, go the quick-and-dirty philosophical route, which has the benefit of being much more energy efficient and laying its cards on the table. Prove that you are imagining or acting rather than executing or behaving. Prove that your concept that you are imagining is not the very thing that humans have been programmed to picture about themselves! Like Descartes you will find there is no way out of this bind. Everything you can think concerning your personhood could be an artifact of being an android.

What are we to conclude from this? That you’re not a person? Far from it. What we conclude is that our concept of person must be inaccurate. It is far too rigid and dogmatic. Perhaps people are cheaper than we like to think. Perhaps it’s not so difficult to be a person, because person isn’t quite as intense as all that. Not that there are no people, but that person is cheap. Lo and behold, we have just extended personhood to nonhuman beings, without discriminating between conscious and nonconscious, sentient and nonsentient—or for that matter alive and not-alive. Person is a spectral category that can apply to all such beings.

Far from thinking personhood as a special emergent property of special interactions of special algorithmic processes (or whatever), this way doesn’t depend on reductionism at all. Strangely, cheap personhood is far more resistant to being reduced to atoms or brain firings than the expensive one! We don’t need to specify that personhood emerges from states of matter (or organization of subsystems or what have you), or that personhood is some special extra fact (such as a soul) added mysteriously onto matter (the Cartesian solution). Personhood is a widely available (in fact, universally available) category, flimsy, subscendent and spectral. We have just admitted that everything might be a person. Part of this admission is that we are caught in the subjunctive mode that Descartes wants to collapse into the indicative. “I might be an android” is as unacceptable to him for its “might” as for its “android.”

Such a thought process wants to eliminate doubt and paranoia. But what if doubt and paranoia were default to personhood? What if being concerned that I might not be a person were a basic condition of being one? This seems to be what the Turing test is pointing to. It’s not that personhood is some mysterious property that we grant to beings under special circumstances, or that it doesn’t exist at all except for in the eye of the beholder, or that it’s an emergent property of special states of matter. It’s that personhood now means “You are not a non-person.”

In the UK, there is an urban myth about the legal definition of “not being in possession of yourself,” aka “not being a person.” Someone, such as a lawyer, needs to go beyond philosophical niceties and define, using some empirical signal, supposedly transcendental concepts such as person, something lawyers argue and argue about regarding, say, chimps in zoos.

The urban myth says so much about how we still regard being a (human) person as (paradoxically) the property of a subject (at the very least, this is an infinite regress and, of course, it’s absolutely ecological violence enshrined in law) and as a mind in a body, with an unmentionable interface between them whose operation remains obscure. Legend holds that if you have taken more than five hits of acid, you are not in possession of yourself and cannot testify in court. Evidently there is a double standard here—chimps have on the whole done less than five hits of acid … There is an ontological assumption about chimps at work. There is an implicit acceptance that vague bundles of things can exist: otherwise the sorites logic would apply. One hit—still a person? Yes. Two hits? Yes. Three hits? Yes. You can keep adding hits to the person and the same logic will apply.

My flimsy yet significant, spectral being is well illustrated by the following fact, which we can demonstrate using arguments from utilitarianism. Ecological phenomena such as global warming and radiation last tens of thousands of years. Over that time span, the following will be true:

(1) No one will be meaningfully related to me.

(2) Every action I do now will have a greatly amplified significance.6

My effects on the world will have been immense. But I qua Tim Morton won’t matter at all. My specific personhood has become ethically cheap, while the effects of my existence on other beings in the world have become supremely urgent. It is as if I have become a poltergeist, visible only in the shattered cups and weirdly opened doors I have left behind.

The “alienated essence,” or non-Althusserian argument, is right for the wrong reasons. We have been alienated, but not from some consistent self-present essence. We have been alienated from spectral inconsistency. We have been Severed. The “nothing outside of ideology,” or Althusserian, view is wrong for the right reasons. The human is indeed produced by language, discourse, correlation, economic relations and so on, such that there is nothing “behind” ideological appearances. But there is something in front of appearances (ontologically in front, not spatially), an inconsistent spectral essence we are calling humankind. Humankind is not despite appearance, nor produced by appearance. Humankind’s essence is futurality, a not-yet quality that resides in front of how humankind appears—which is why we can’t see it, because we are it. And this futurality is not special to humankind, but rather shared by coffee mugs, galaxies and trade unions.

We have generated a new theory of ideology. There is “nothing” under appearance, but not because appearance is all. Appearing is totally intertwined with being, and being withdraws. So, the appearance is always a distorted, low-amplitude rendition of the spectral X-powers of a being. What capitalism distorts is not an underlying substantial Nature or Humanity, but rather the “paranormal” energies of production.

ADVENTURES ON THE SPECTRAL PLAIN: RACISM AND SPECIESISM

“This is my land, by definition, and I have the right to dispose of whatever else is on my land in whatever way I see fit.” That “dispose of” should alert us to how the notion of private property is tied to the notion of liquidation. On this view, a landowner has the right to kill whatever lifeforms are on their property.

Which comes first, racism or anti-environmentalism? This has to do with a deep philosophical issue: which subtends the other, racism or speciesism? Does racism exist because we discriminate between humans and every other lifeform? Or does speciesism exist because we hold racist beliefs about people who don’t look exactly like us?

Consider the fact of land ownership as republican qualification for voting rights in the eighteenth century. Voting rights were tied to slavery. Surely this phenomenon is part of the legacy of agrilogistics, and its construction of a caste system. The caste system distinguishes between humans; then the distinction is mapped onto nonhumans. The tendency to see nonhumans as unthinking and even unfeeling machines is predicated on the objectification and dehumanization of other humans, not the other way around. It is racist to suppose that some humans are degenerate, resembling apes for instance, not because apes really are degenerate. The degeneracy of the ape is a negative projection, not unlike the projection of positive human qualities “upwards” to a deity. The very concept of race as an ontically given reality, as in the anti-Darwinist racism of the biologist Louis Agassiz (his categories, such as “Caucasian,” still grace some paperwork), is itself racist, and for this very reason: the idea that there are ontically different “races” as if there were different species. (This is drastically different from claiming that racism doesn’t exist, as in the habitual right-wing blindness to the category of racism as such.)

The struggle against racism is exactly the struggle against speciesism, which is one of the ways maintenance of Nature works. Totalitarian and fascist societies can be weirdly ecological, in ways that disturb us about ecology: like eugenics, or animal rights (the Nazis were all over that), reforestation—think Lenin talking about putting loads of fertilizer in the soil. In the case of fascism, what is imagined to be the cause of the degradation of the people is what is held to be abject and uncanny, pathologically “unclean,” and this politicized disgust surely does resonate with some kinds of ecological awareness: our symbiotic coexistence exceeds neat concepts of boundaries. The point, however, is that one can’t get rid of the abject, “unclean” and uncanny beings without immense and escalating immunitary violence. This is obviously because symbiosis is not an optional extra: one cannot peel everything off or heal one’s intrinsic brokenness, because the nonhuman being stuck to you is a possibility condition for your existence. With his moody ennui, Baudelaire shows how to tunnel down into deeper ecological awareness underneath fascism. Instead of trying to overpower the superman, we could slip out from underneath.

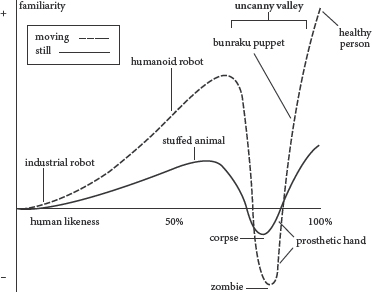

We make beings extermination-ready by designating them as uncanny, disturbingly not-unlike-us-enough beings that inhabit the Uncanny Valley. In robotics design, it is frequently said that as android designs approach close resemblance to humans, they enter the Uncanny Valley, populated at its nadir by the zombie, an animated corpse. At a certain point of closer resemblance, our identification with the android ceases to be uncanny.

Figure 3. The Uncanny Valley (Masahiro Mori)

The Uncanny Valley concept explains racism, and is itself racist and, in addition, profoundly ableist. On one peak resides the so-called “healthy human being.” On the opposite peak, waving to us cutely, are nonhuman beings who look unlike us enough not to provoke the uncanny reaction. R2-D2 and Hitler’s dog Blondi are “over there” on the peak opposite us, the good, fascist “healthy human beings.” Racism tries to forget the abject valley that enables this nice me-versus-nature, human-versus-nonhuman, subject-versus-object and health-versus-pathology setup to work. But these peaks are illusions, and there is no uncanny valley, because everything is uncanny, because we can’t say for sure whether it’s alive or not alive, sentient or not sentient, conscious or not conscious, and so on. Everything is spectral, undead, in unique and different ways. The Uncanny Valley flattens out into the Spectral Plain. Speciesism exists because humans can be differentiated decisively from nonhumans. And they can be because of racism: because the deep trough of the Uncanny Valley separates humans from puppies in a clean-seeming way, as long as we ignore the beings who have been thrown into the Valley of pathologized abjection. Speciesism depends on the dehumanization of some humans, with anti-Semitism as its template.7

Freud argues that the uncanny is keyed to realizing that we are embodied beings.8 And what is more embodied than being a part of the symbiotic real? Doesn’t the uncanniness of beings caught in the Uncanny Valley have to do with how they remind us of the non-manipulable, embodied, “less than human” aspect of ourselves, our very species-being? The struggle to have solidarity with life-forms is the struggle to include specters and spectrality. Without this, ecological philosophy falls into a gravity well where it becomes part of the autoimmunity machination just described.

Let’s reverse engineer a concept from the Uncanny Valley. There’s a phylogenetic part (the caste system is derived from agrilogistics), and there’s an ontogenetic part (humanoids, hominids, hominins, primates and so on). The human body is a historical record of nonhuman evolution. Racism has to do with thinking one can point to certain physical features as indicators of the proper: it has to do with a metaphysics of presence and a substance ontology whereby one color is non-marked (it’s not treated as a color but as the default quality of the substance, totally bland, “white”).

The struggle against racism is thus also part of the deanthropocentrization project. Whiteness, after all, is a direct artifact of the type of agricultural logistics that severed human–nonhuman ties. Wheat was farmed in areas in which it lost much of its nutritive value. At higher latitudes, wheat can’t produce enough vitamin D to prevent humans from getting sick, unless humans become more efficient solar processors of the vitamin D in sunlight. Whiteness is therefore very recent and ecologically disastrous, since it was historically intertwined with speciesism. The program that brought us white bread also brought us whiteness as such.