In the twenty-first century, owning a single-family home has come to represent much more than the security and safety afforded by basic shelter. In many cases, it is seen as the visible demonstration that its owner has achieved some semblance of the good life presumably sought by all human beings. In the Introduction we discussed the phenomenon of house addiction, and argued that this addiction has led us on a self-destructive binge that could blow up in our faces. In chapter 1, we sketched a broad history of household dynamics and described some demographic drivers of the housing bomb. In this chapter, we focus on the social construction of relations between person-hood and home. We ask how home ownership became so closely identified with personal happiness and social status, how owning a single-family home became synonymous with patriotism, and how these attitudes and beliefs influence household dynamics today.

It seems relatively clear that home ownership conveys benefits in the form of transaction savings, because once one has purchased a home, negotiations with a landlord are eliminated. In many nations, legislation and other rulings enhance the benefits of home ownership by providing legal means for homeowners to extract funds from society, including from those who are not homeowners. It also may contribute to efficiency, as homeowners accumulate local knowledge through longer tenure in a single location. But somehow, home ownership has developed a cultural significance that extends far beyond what would be suggested by these advantages.

From today’s perspective, it seems obvious that single-family home ownership is universally valued; it conveys status, security, and freedom to home-owners. When we use the term home ownership, we are referring to owner-occupied residential real estate, not structures purchased for other purposes. And, at least in the United States and Britain, the homes we are referring to are primarily single-family dwellings.

People have been congregating into various forms of municipalities for a very long time, at least since the era when humans figured out how to organize themselves in ways that enabled them to stockpile concentrations of surplus products.1 The values and beliefs that undergird today’s household dynamics, however, are much more contemporary. Although most analyses of the ideology supporting current home-ownership patterns have been based on British and other Anglo-Saxon cases (including the United States), the relevance extends far beyond them. These home-ownership patterns, although largely developed in the West, have been wholeheartedly exported to other nations and regions, such as Hong Kong, India, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan.2

Humans need some sort of shelter, and ownership of a single-family home is widely thought of as the preferred way of obtaining that shelter. When we were writing this book, the National Association of Realtors (NAR) was airing the following advertisement on radio and television throughout the United States:

When you’re a kid you don’t know much about housing markets. You don’t know that home ownership builds communities. And you certainly don’t know that owning a home contributes to higher self-esteem and better test scores. You just know that home is where you belong. It’s where you play, grow, and learn. The National Association of Realtors wants you to know that home ownership matters: to our families, our neighborhoods, and our country.

Audience members were encouraged to go to the NAR website to learn more about home ownership (www.realtor.org/videos/public-advocacy-campaign-moving-pictures/). On the website, we found a news release dated June 27, 2012. The text reassured readers that the NAR understands that “there’s a reason home ownership is called the American Dream…. Realtors remain committed to keeping the dream of home ownership alive for generations of Americans” (www.realtor.org/news-releases/2012/06/home-is-where-the-history-is/).

Many in this country live the American dream of home ownership, but the British rate of home ownership slightly surpasses that of the United States. Margaret Thatcher’s conservative variation on the idea of a property-owning democracy increased the proportion of British homeowners while contributing to increased disparity in both income and wealth.3 The Housing Act of 1980 provided a powerful policy arm to Thatcher’s belief in privatization.4 It gave tenants living in social housing (rental housing owned and managed by the state and/or a nonprofit organization) the right to buy their residences, usually at a discount from temporarily inflated market rates. Proponents proclaimed that the Act enabled working-class British citizens to cross that stark divide between those who have capital assets and those who do not. At the same time, opponents argued that it would dispossess those who were the most needy.5 Either way, the 1980 home-ownership rate of 55% grew to 67% by the time Thatcher left office in 1990, and later increased to beyond 70%. Although many of those new homeowners have now become homeless, due to the recent financial bust, their loss does not change the fact that, when given the opportunity to purchase their homes, residents of social housing did so in droves, despite outrageously inflated prices.6 The perceived advantages of home ownership have led to increased levels of owner occupation in several nations. Although Anglo-Saxon countries have promoted home ownership more strongly than those in continental Europe, various modes of supporting home ownership are now practiced in most developed nations.7

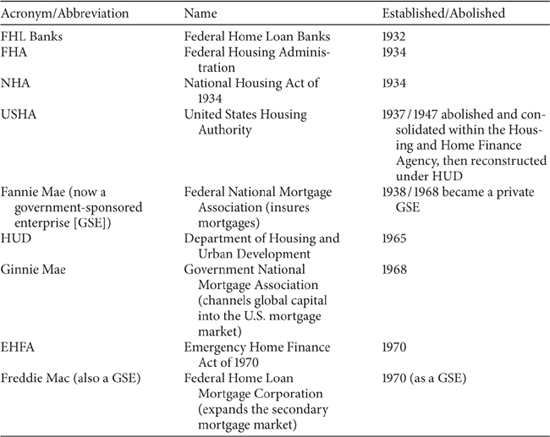

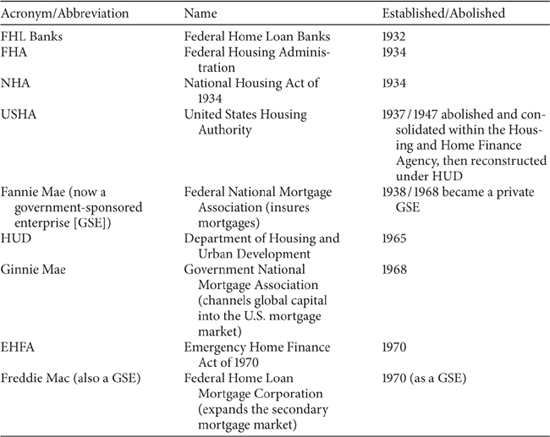

Taking the United States as an example, historical accounts indicate that, although a preference for home ownership over renting has existed throughout U.S. history, the belief that home ownership is both a basic right of and a responsibility for all citizens was just reaching maturity in the years following World War II, and it required considerable effort on the part of both the public and private sectors to reach that point.8 Although financing options were limited in the late 1800s and early 1900s, “it was not financial ability that kept old-stock Americans from buying homes; buying simply was not that important.”9 Further, home ownership conflicted with Americans’ desires for mobility. Persuading Americans that they wanted to own their own homes required massive campaigns carried out by a partnership between the public and private sectors. We briefly describe the main characteristics of these campaigns here, and then suggest reasons why the nation-state poured resources into them. (Table 2.1 offers a summary of especially significant U.S. agencies and government-sponsored private-sector institutions associated with home ownership).

The federal government’s foray into housing began in earnest in 1917, when the U.S. Housing Corporation started working with private developers to build “affordable housing” for workers who were contributing to the war effort. Federal campaigns, working in partnership with national and local real estate organizations, publicly associated owners of single-family homes with thrift, moral character, and citizenship, and homeowners were lauded as patriots. At the same time, the rhetoric of these campaigns associated renters and those living in multifamily dwellings with negative concepts, such as communism and radicalism.10

Table 2.1 Important U.S. housing programs during the twentieth century

Campaign publications portrayed both multifamily housing and tenancy as undesirable, stating that “in the minds of many it threatens American institutions.”11 At the same time, real estate agents began using the presence of homeowners to signify a neighborhood’s superior quality, such as in this advertisement in the Atlanta Journal: “Davis Street is settled with a good class of people, most of whom own their own homes.”12 As Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover opined that home ownership “may change the very physical, mental, and moral fiber of one’s own children.”13 Paul Murphy, head of the U.S. Department of Labor’s Own Your Own Home campaign, proclaimed that “man must provide for his family by building a home, else he robs his patriotism of practicability.”14 Pronouncements such as these were inserted into pamphlets given out at women’s clubs, work sites, and public schools. Americans apparently took a considerable amount of persuading, and a publicity agent within the government proclaimed that “[dissemination through these venues] is exactly the thing needed to shove the whole housing and better homes ideas of the Department over.”15

Prior to these campaigns, the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB) had not focused on selling single-family dwellings.16 As a signal of its new emphasis, NAREB wrote the following to its members:

Realtors: You have a definite duty. Aside from your natural wish to dispose of property on your lists, you have a patriotic call. The nation looks to you for education! Put a shoulder to the wheel! Get into the human side of present conditions. Teach the nation that there is one duty [ownership of a single-family dwelling] none should shirk.17

NAREB accepted the responsibility to teach Americans that every male citizen needed his own single-family home to provide the ideal environment for family life, especially child rearing. Owning such a home contributed to thrift and independence. The desire to own one’s (detached) home was described as natural, which may be why apartment living was cast as detrimental to both personal and family life. Further, home ownership conferred status rewards, because homeowners were proclaimed as bulwarks of the community and the American way of life. Apartment dwellers, on the other hand, were described as more likely to be socialists, criminals, and therefore contributors to social disorder in the neighborhood.

Robert Lands notes that “by imbuing home ownership with particular meanings, federal and private interests were able to entice Americans into adopting practices and frameworks that served a number of national interests, including the stabilization of land markets and the adoption of specific political frameworks.”18 Slogans such as “A man’s home is his castle” and “Home is where the heart is” gained enormous popularity, and they are still in vogue today.

Even with these enticements, the state of home ownership in American society remained radically different from what we know it as in the twenty-first century. Before the National Housing Act (NHA) was passed in 1934, the banking system required prospective homeowners to produce down payments equal to or larger than the size of the loan, which was beyond the financial means of many Americans.19 Thus, despite campaigns glorifying home ownership as the material embodiment of the American dream, the ownership rate hovered under 40% until institutional changes loosened the market further.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s programmatic response to the Great Depression included both the massive development of various infrastructures and institutional changes to encourage citizens to purchase homes. Housing, which remained the biggest untapped loan market in the United States, was the target of the NHA. The NHA was expected to stimulate the severely depressed economy by awakening this sleeping giant. The Act included the establishment of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), to supply the needed institutional boost. This governmental agency would provide insurance to private banks, especially those that made loans to low-income families who had previously been unable to enter the market. The goals of the FHA were to improve housing standards and conditions, provide an adequate home-financing system, and stabilize the market, all through insuring mortgages. Insurance supplied by the FHA provided banks with a sense of safety, encouraging them to make loans to the low-income borrowers they had previously avoided. Since the new mortgages required lower down payments and offered loan packages spread out over a longer period, borrowers could qualify more easily. Not surprisingly, home ownership rose from 41% in 1941 to 57% in 1957.20

These home-owning patriots streamed out of urban centers and into the suburbs, and they did so in a highly racialized pattern. Despite the rhetoric, the new mortgage industry did not create a society where all residents (or even all citizens) could own their own homes. In fact, the transformation may have solidified the boundaries between homeowners and renters, along with the social status associated with each.

At roughly the same time as institutions such as Fannie Mae and the Veterans Administration were opening up the mortgage industry to previously ineligible borrowers, another governmental agency was producing housing for those who still remained outside the market. The U.S. Housing Authority (USHA), created in 1937, focused on providing decent housing, even for those who still could neither pull together the required money for a down payment, nor qualify for the liberalized loans. To do so, the USHA loaned money to municipalities. These municipalities, in turn, were required to tear down slums and replace them with public housing that would be available to the poor.

Concerns that the widespread availability of this public housing might interfere with burgeoning real estate development led to policy decisions that severely limited tenancy, restricting it to the very poor. Cultural traditions combined with political power to ensure that public-housing projects were vigorously segregated along racial lines. When the Supreme Court began striking down the constitutionality of segregation with decisions such as Shelley v. Kraemer (1948; 334 U.S. 1) and Brown v. Board of Education (1954; 347 U.S. 483), it became clear that racially segregated public housing could not be maintained. After 1954, blacks began moving into public-housing communities that had previously been reserved for whites. Many of the white tenants, their minds still teeming with racist fears, migrated to the suburbs as soon as they could put together a down payment.21 Thus, at the same time that tenancy in public housing became increasingly identified with impoverished inner cities, home ownership became increasingly linked to America’s prosperous suburbs.

The U.S. citizens who remained behind in the inner city, still unable to purchase a home, could be easily identified by the color of their skin. Despite decisions such as Brown v. Board of Education, segregation in the United States did not disappear overnight. The quickly constructed subdivisions that provided affordable new homes were energetically segregated, with full support from residents, realtors, developers, and lenders. If black citizens actually looked for a home in these locations, they would be told that nothing was available.

Both public and private policy colluded to maintain segregation between white citizens who could buy their own homes, and black citizens who could not. The FHA’s Underwriting Manual, published in 1935, mandated that a neighborhood have “protection against adverse influences,” noting that “important among adverse influences are the following: infiltration of inharmonious racial or nationality groups; infiltration of business or commercial uses of properties; the presence of smoke, odors, fog, heavily trafficked streets, and railroads.”22 The private sector was squarely on board. As late as 1950, the NAREB Code of Ethics stated:

A Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood a character of property or occupancy, members of any race or nationality, or any individual whose presence will clearly be detrimental to property values in the neighborhood.23

The FHA contributed further to congregating blacks in public housing projects by redlining (marking a red line around) minority neighborhoods as risky ventures that mortgage investors should avoid.24 Although the practice of redlining was made illegal by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, it has had long-lasting effects on black and other minority communities. Contemporary inequities in private-property ownership by minorities can be traced directly to FHA regulations during the New Deal era. As white middle-class home owners flocked to the suburbs, owning houses with federally insured mortgages, blacks moved into public housing that white tenants had previously occupied. Because minority neighborhoods were designated as blighted, mortgages were less easily available for blacks who wanted to purchase homes there. Without the financial incentives available for suburban development, property values for homes in inner-city minority neighborhoods plummeted. Moreover, although the new suburbs continued to draw services from the urban core, the urban tax base all but disappeared.

Almost a century after politicians and property developers collaborated to liberalize mortgage standards as one means of reinvigorating the ailing U.S. economy, home ownership has achieved what Stephanie Stern calls “an exalted status and privileged position in American property law.”25 She cites bankruptcy protections, property-tax relief, and foreclosure reform as examples of what she terms “residential protectionism.”26

Although it imposes tremendous costs on society in general, as well as on people who rent their homes and on apartment dwellers, the concept of single-family home ownership is protected from critical evaluation by its “stature of moral right.”27 Scholarship regarding property issues relies heavily on Margaret Radin’s largely unsubstantiated theory that a special class of property, including homes, is rooted in the constitution of the self, so that home ownership becomes a basic human right, on a par with life and liberty.28 Thus what might otherwise be seen as policies that encourage irresponsible behaviors—such as rent seeking, boosterism, and land speculation—have been promoted as morally unimpeachable. Rent seeking refers to a situation where an individual or organization obtains an economic gain from others without any reciprocal benefits coming back to society through the creation of wealth. We are using the term boosterism to describe promotional activities often associated with extravagant predictions and inflated prices for real estate. Land speculation often results from successful boosterism, with prospective homeowners purchasing risky property investments that offer the possibility of large profits, but also include a higher-than-average probability of devastating loss.

Before leaving the question of whether home ownership is a sacred human right, let us engage in a thought experiment. Imagine that private-property policies were truly motivated by the belief that one’s home is an extension of one’s self, a psychological prerequisite for mental health. In that case, there would be no reason to privilege a traditional single-family residence over other sorts of homes. Since each person is a unique individual, a person’s home could be expected to come in any imaginable shape, color, and size to fit the person for whom it is an extension. When someone wants to make their home in a school bus, a railroad car, or a truck bed, however, property law not only fails to provide protections for such homes, it tends to prohibit them. If this imaginary scenario seems ridiculous, perhaps it is because home ownership comes closer to being a sign of social status than an extension of the self. But protecting someone’s social status does not have quite the same moral authority as safeguarding someone’s personhood.

If home ownership does, indeed, create an extension of the self, it makes sense to provide security for it, and society has done so, at tremendous cost. These protections encourage excessive investments in residential real estate, narrowing the options present in a society’s investment portfolio.29 State laws that cap property taxes on homes benefit longtime owners at the expense of both new buyers and renters.30 Homeowner protections also increase the cost of credit for everyone else, a cost that is experienced most heavily by poor families.31 Home protectionism makes community planning more difficult, and encourages sprawl (see chapter 6). Sprawl, in turn, exacerbates anthropogenic (related to or resulting from the influence of humans on nature) climate change by continually boosting demands for consumer goods and fuel for the motor vehicles that we rely on to make suburbia appealing.32

Given the tremendous costs of residential protectionism, it seems reasonable to expect significant empirical support for the psychological benefits of home ownership. Susan Stern found an astonishing lack of such support, however.33 For example, although homeowners use their homes to display or advertise their identities, there is no empirical evidence that home ownership makes important contributions to a person’s psychological health, or that a lack of home ownership threatens it. There is evidence, however, that dislocation occurs more often among renters than among homeowners, although it is not clear whether forced, rather than voluntary, dislocation is more frequent among renters. Homeowners may face forced dislocation due to mortgage foreclosures and the exercise of eminent domain. Renters may also encounter forced dislocation when these situations arise, as well as in instances when the needs and desires of the people who own the lodgings change. Dislocation, especially when forced, does contribute to short-term stress, but stress levels quickly return to the same levels people were experiencing prior to the dislocation.

The ownership of private property confers both comfort and status on people, especially those living in capitalist societies.34 But there is a striking lack of evidence to support the emphasis on residential real estate as a special case of property. As Stern argues, “The empirical evidence indicates that the psychological and social importance of the home has been vastly overstated. The psychological value attributed to the home has masked rent seeking as moral conviction and greased the wheels of the residential protectionism machine.”35

Home ownership, by increasing social capital, has also been touted as a strong contributor to closely knit communities. Social capital, in this case, refers to benefits (often economic) derived from cooperation between tightly knit groups of people.36 Theoretically, communities with more volunteer organizations, more people meeting and greeting on the street, and residents who have lived there for a considerable time would have stronger and more valuable relationships than communities where residents are isolated and have short residency periods. Some property theorists have argued that protecting home ownership increases social capital by creating strong and meaningful social ties within the community.37 Again, the empirical evidence does not bear out the claims. It is true that neighborhoods dominated by owner-occupied houses are more stable than those dominated by renters, with owners moving somewhat less frequently. Rather than discovering links between residential stability and tightly knit communities, however, the empirical evidence indicates that neighborhoods dominated by homeowners display the same declining sociability as neighborhoods composed primarily of renters.38 Further, as we will demonstrate in chapter 6, the dominant form of modern suburbia clearly harms social capital by forcing people into automobile-based transport and off of sidewalks and streets where they might interact with their neighbors.

Even in matters where there is a measurable difference between the behaviors of homeowners and renters, when models control for other variables, a rather confusing picture emerges. Although homeowners are more likely to vote and to join neighborhood volunteer organizations than renters, if home ownership is decoupled from tenure (the length of time spent living in a place), most of the difference disappears.39 Length of tenure, by itself, appears to contribute significantly to social capital by increasing the number of weak ties between individual community members. Yes, home ownership is associated with a lesser degree of mobility (e.g., in changing residences), but any policy to further limit mobility will increase the level of residential investment in the local community.

The decision to limit where people live, however, is not without its down side. Luckily for the majority of people who remain relatively mobile throughout most of their adult lives, communities are bound together by a dense mat of weak ties, not by strong ties. Politically active communities rely primarily on weak ties, which are typically reestablished within 6–18 months of a move.40 Limited mobility may lead to greater stability, but stability does not necessarily lead to culturally, economically, and politically vibrant communities. We have all traveled through neighborhoods that seem to have grown old along with their owners, and although they may exude serenity, more often they just seem tired. Migration facilitates cultural, economic, and political vitality, since migrants may introduce new norms, values, and social practices that might foster adaptability.41 All communities face problems, and given the rapid pace of change in modern society, responses that worked ten years ago probably are not sufficient today. Mobility provides a relatively non-threatening reason to reshape social relationships and institutional structures that have become outmoded. Observing migrants as they learn the norms of their new community provides longtime residents with opportunities to rethink automatic behaviors. The reciprocal learning that emerges from the process of new residents becoming embedded in new social networks lends resiliency to both individual participants and the community.

Although there are many reasons why we may choose to retain the complex network of special protections afforded to owners of single-family homes, we should not do so under the illusion that we are safeguarding people’s personal psychological health or conferring unique social benefits on the community. The current approach to individual home ownership and housing development privileges a small group of elites and limits social adaptability.42 Further, current household dynamics are devastating from an ecological perspective. Concerted efforts to encourage home ownership clearly increase the human footprint on the environment, because multiunit buildings are far more common for rental markets than for ownership of individual units. Although national data on rentals is limited, the United States began collecting this information in 2012. Those data will confirm what we already know: rental housing is smaller in size and, on average, more dense than owner-occupied housing. The 2010 census data showed that single-family homes were nearly twice as large (2,500 square feet) as units in multifamily buildings (1,400 square feet). So what are the compelling economic and political rationales for the policies that have enabled the development and maintenance of this unsustainable system of household dynamics? What justifies providing greater protection for ownership of detached single-family homes than for ownership of other types of property?

From today’s vantage point, it seems obvious that increasing the number of homeowners made financial sense to a nation struggling to dig its way out of an economic depression. Yet the promise of an immediate economic reward provides only a partial answer. In the United States, the strategy of using widespread ownership of small landholdings to alleviate political tension dates at least to Jeffersonian efforts to stabilize the young republic by spreading ownership of its productive land as broadly as possible. Jeffersonian agrarianism posited that because yeoman farmers lived on their own land, they were independent of society for life’s necessities (food and shelter) and dependent on it for protection and laws.43 Because they possessed property, they were bound to defend the political system that sustained their property ownership, and in defending that system they stabilized it in the face of attempts to alter existing political arrangements.

Although Jeffersonian agrarianism had portrayed urban dwellers in derogatory terms similar to those used later for apartment dwellers by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Own Your Own Home campaign, the concept of property ownership as a stabilizing force easily transitioned from farm ownership to single-family home ownership. In the face of widespread fears of social unrest associated with domestic industrial struggles, urban riots, communism, and anarchy, ownership of a single-family home came to symbolize patriotism and loyalty to the United States. Robert Lands noted that in the 1920s, “federal initiatives publicly associated the homeowner with thrift, character, moral fiber, and citizenship. [Their rhetoric described homeowners] as patriots and family providers, the bulwark of the nation-state.”44 In 1923, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover claimed that suburban home ownership provided “the foundation of a sound economic and social system and a guarantee that our society will continue to develop rationally.”45

Suburbanization entailed a radical transformation in lifestyles, which has been especially useful for powerful economic and political elites, allowing them to maintain control over the populace. First, it created needs for new products, ranging from air conditioning to multiple personal motor vehicles for each household.46 Second, the fact that middle-class home ownership has been dependent on heavy federal subsidies helped alter the political landscape and focused community organizing on the defense of property values. Third, as debt encumbered homeowners, suburbanites helped weaken the threat labor posed to management, because workers could not afford to go on strike; without a paycheck, they couldn’t make the next month’s mortgage payment.47

Using home ownership to maintain social order and legitimize capitalist socioeconomic relations is not unique to the United States. There is strong evidence that home ownership has been politically sponsored to stabilize civil society by offering citizens a stake in a property-owning system; and it appears to have worked.48 Since the 1980s, private ownership of homes has been particularly effective in buttressing neoliberal economic policies. Even in China, a nation that has only recently emerged as a powerful capitalist economy, home ownership has contributed to the rapid expansion of a neoliberal ethos.49 Amid Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms in the early 1980s, markets were significantly liberalized, an entrepreneurial class was assembled, and an economic elite was reconstituted. The members of the entrepreneurial class, while not among the elite, have become ardent supporters of the political regime that has granted them the right to purchase private property and to use the credit system. Because this class’s new ownership status relies on absolute political stability, the growing inequality between prosperity and poverty across different regions is ignored in what David Harvey describes as “a radical means of accumulation by dispossession.”50

The same approach is illustrated in a recent World Bank report on international development. It recommends that developing countries move toward the system of home ownership favored in the United States: “Occupant-owned housing, usually a household’s largest single asset by far, is important in wealth creation, social security, and politics. People who own their house or who have secure tenure have a larger stake in their community and thus are more likely to lobby for less crime, stronger governance, and better local environmental conditions.”51 If the goal is to promote political stability, the best tactic is to make every citizen a homeowner.

Scholars, accepting the evidence that property ownership tends to stabilize the existing political regime, have turned to the question of who this stability serves, noting that while maintenance of an unjust social system may be ideal for the world’s wealthiest people, others may find it less appealing.52 This leads to questions of whether the urge to protect prevailing social structures led to the sanctity of home ownership, or whether it worked the other way around. From our perspective, it makes more sense to assume that prevailing social structures and the dominant ideology about home ownership have codetermined each other. Further, although we agree that it’s important to know how we got to the point where home ownership is widely believed to be a fundamental human right, we are more concerned with understanding how current policies that have emerged from uneasy relationships between culture, economics, and politics drive contemporary household dynamics.

As we mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, home ownership conveys benefits to the individual homeowner, but those benefits do not necessarily translate into benefits for society. There is no question that current U.S. policy, both at state and national levels, redistributes wealth by extracting rent from non-homeowners and paying that money to homeowners.53 The question is whether or not this redistribution is good for society. We should also note that the redistribution that occurs through residential protectionism is regressive. It privileges higher-income households (through a form of subsidy) at the expense of lower-income ones. The federal income-tax deduction for mortgage interest, a loss to the government of over $72 billion annually in revenue, provides larger subsidies (deductions) to higher-income homeowners, who generally have bigger houses, with more substantial mortgage payments. Similarly, renters pay property taxes indirectly through their rent (as taxes are usually a factor when landlords calculate rental fees), but landlords get to include these property taxes among the itemized deductions on their income tax forms.

Residential protectionism also slows society’s ability to respond to shifting employment needs, frustrates land planning, and encourages people to sink all of their investment potential into residential real estate, which means that their retirement portfolios completely lack diversification. We might even argue that current policies regarding home ownership display blatant code-pendency and encourage irresponsible social behavior. For example, during the 1980s and 1990s, people in many regions of the United States purchased homes at grossly inflated prices, sinking all they had (and committing much that they did not have) into the irrationally optimistic hope of continued rapid price increases for housing.54 When it became clear that the flood of foreclosures was not going to stop with just poor and blighted areas, the sub-prime mortgage crisis was declared. In response, the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 required lenders to forgive debts above 90% of the appraised value of owner-occupied residential real estate, and it then allowed the homeowners whose debts were forgiven to refinance with mortgages insured by the FHA. The federal government, supported by private mortgage lenders, stepped in to enable insolvent house addicts to continue their self-destructive behaviors. But, as with any codependency, the Act has a catch. When these homeowners eventually do sell their houses, they must pay the FHA at least 50% of any appreciation in the value of their homes. Moreover, if they sell within five years after refinancing, they have to pay the FHA an additional premium, calculated according to the number of years from the refinancing date to the sale.

Paul Krugman contends that, when removed from the elaborately woven safety net provided by the United States and several other nations, homes emerge as high-risk, undiversified assets that are far from the best investment for most people.55 The claim that homes deserve protection because they are “an owner’s largest asset” merely naturalizes (establishes as a common practice) an unhealthy cycle: a home becomes the owner’s largest asset because of legislation that gives special privileges to residential property, and it then requires additional protection because it has now become the owner’s largest (and sometimes only) asset.

Although non-homeowners bear the heaviest cost, homeowners also pay for the privilege of possessing a single-family dwelling. Social costs imposed on owners include limited mobility in response to changed personal circumstances and professional needs, and a disproportionate amount of their investments channeled into a single asset. Empirical evidence shows that, if home ownership does have an influence on people’s basic psychological health, it causes psychological harm to low-income owners.56 Further, home ownership actually has negative health effects for people who form the most vulnerable sector of the population, those who already suffer from poor health.57 This is not to say that private-property ownership is not important. Some amount of private-property ownership is a high priority for people, but there is no evidence to support the special status given to single-family homes over other forms of private property.

Ironically, the independence supposedly accrued by owning a single-family home is heavily dependent on a complex network of property, bankruptcy, and tax laws.58 Governmental subsidies perpetuate the myth of the independent homeowner at the same time that they undercut its believability. We are not arguing that subsidies are always a bad thing. There is nothing inherently wrong with using economic and other incentives to encourage behavior that results in either short- or long-term benefits for society. But it may not be a good idea to subsidize behaviors that do not provide significant benefits to society, and, in fact, impose significant costs.

Homeowners, especially those who depended on mortgage liberalization to purchase their homes, are particularly vulnerable to economic cycles. In 2006, the rate of foreclosures within low-income areas of U.S. cities began to increase.59 There was little outcry, however until mid-2007, when the foreclosure wave began to engulf white middle-class suburbs, especially in the South and Southwest. By the end of 2007, approximately 2 million people had lost their homes, and there was no sign that the problem was slowing down. By the end of 2008, in the midst of what the media had christened the subprime mortgage crisis, all of the major Wall Street investment banks had collapsed (or gone through forced mergers), and confidence in the global financial system plunged. The crisis didn’t stop with the banks, but soon engulfed those institutions that had been set up to insure mortgage debt (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac). By early 2009, the U.S. mortgage crisis had spread across multiple economic sectors, as well as the rest of the globe. The celebrated growth economies in South and East Asia, for example, began contracting at a frightening speed.60

Although the global economic meltdown involved much more than just household dynamics, that is where it began. And we see little evidence that people have learned from this crisis. A recent World Bank report on international development recommended that developing countries establish the very system that had so recently crashed in the United States, suggesting that “when a country’s system is more developed and mature, the public sector can encourage a secondary mortgage market, develop financial innovations, and expand the securitization of mortgages.”61 Apparently home ownership, mortgage financing, and securitization will magically transform poor nations into economically prosperous and politically stable countries. The authors of the report either failed to notice, or did not care, that this system is currently leading to mass dispossession and the loss of assets for the most vulnerable populations in the United States, Britain, and other nations.

Despite the accepted definition of crises as events that pass quickly, the housing markets in the United States and numerous other nations have yet to rebound to pre-crisis levels. The subprime mortgage crisis may even pale in comparison to housing crises associated with baby boomers retiring and trying to sell their high-priced homes.62 Dowell Myers and SungHo Ryu have noted that the 78 million baby boomers have driven up housing prices since the early 1970s, and the smaller and less economically well-off generations following them will not be able to buy these homes.63 To make matters worse, the upcoming generation of home buyers is far less interested in huge homes on large lots than previous generations, so fewer will buy these homes even if they had the necessary capital.64 Arthur Nelson estimated that in 2003 there were already 22 million more large, detached McMansions on the U.S. landscape than would be needed in 2025, and that the nation faced a shortage of 26 million units in multiunit housing and 30 million in detached small-lot developments.65 This is good news for those advocating efforts to defuse the housing bomb, but bad news for the owners of enormous homes unless someone can devise creative uses for the gargantuan houses, such as dividing them into multiunit dwellings. The latter scenario may be far-fetched, however, since such homes are often far from employment and from public transportation needed by residents who would purchase units in multifamily housing.

The continued homage paid to the current system of home ownership makes little sense, unless the goal is simply to ensure that the wealthiest members of the population continue to distance themselves from the rest of the world. The economic elites of Britain, continental Europe, the United States, and numerous other developed nations compose considerably less than 1% of the world’s human population. Yet these elites retain the ability to dominate decisions related to household dynamics and other important topics because they possess wealth and incomes that can be converted into other resources as needed. Nonetheless, crises repeatedly erupt. We see the globe’s almost continual state of crisis as an indicator that change is possible. And what better place to start than with households?

Despite the fact that the individual emancipation provided by current household dynamics may have been oversold, perhaps continuing these patterns could be justified, because they contribute to society at large. Again, though, we come up against a whole suite of problems. A U.S. Supreme Court decision related to household dynamics illustrates how complicated this can be. In Kelo v. New London (2005; 545 U.S. 469), the Court ruled that the city of New London, Connecticut, was justified in using eminent domain to claim the land where 115 houses stood, in order to sell the property to private developers. In a 5-to-4 decision, the Court stated that New London was not violating the eminent domain portion of the Fifth Amendment (giving states the power to take private property for public use), because the plan promised to benefit the economic development of the entire community, rather than a specific party (individual developers were not named in the plan). Although the developers who purchased the properties benefited from the decision, there has been a strong backlash to the Court’s ruling.

Despite the fact that we are not comfortable with the Court’s decision to forcibly evict householders so private developers could take over their property, we find the passionate public reaction to be more important. Like public support for the liberalization of mortgage markets, public opposition to the Court’s ruling united conservatives and liberals—a rare feat. Conservatives expressed ire that the ruling directly threatened private-property rights, while liberals voiced their anger because it granted wealthy corporations an indirect path to powers of eminent domain. But the public’s emotional fervor goes far beyond these statements of political philosophy. The political fallout from this case has made planning more difficult, constrained economic development, and contributed to sprawl. As part of the public reaction to Kelo v. New London, nineteen states (including Connecticut, Ohio, South Carolina, and Utah) passed legislation restricting eminent domain to blighted areas.66 One result of this legislation is that municipalities and other local governments are now, more than ever, driven to situate public projects farther away from economic centers, where land is cheaper and more easily acquired, even in cases where a public project may have a significant value for the community.

It also provides legal justification for municipalities to target poor neighborhoods when seeking a place to dump unwanted materials or undesirable development projects, since low-income areas are more likely to be designated as blighted than are wealthy neighborhoods. This concern may seem less relevant today, in a world where campaigns to reallocate assets to people currently living in poverty are loudly opposed,67 and schemes to redistribute assets to those who already command the greatest share of them prompt only a raised eyebrow or, at most, a visit to the local Bank of America offices to sing Christmas carols about mortgage foreclosures (www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tns3sljBvxU&feature=topics/).

Although social justice may not currently elicit the considerable attention that it has had in the past, any serious efforts to reconstruct housing dynamics will need to include it. Whether for purposes of social stability or for other reasons, humans have effectively spread house addiction broadly throughout the globe. The World Bank argues that everyone needs to own their home,68 but this widespread expectation simply intensifies the barriers between those who are homeowners and those who aren’t. In a world where mortgages are easy to come by, people who do not own their homes stand out as especially problematic; they may be seen as irresponsible, erratic, or even politically radical.

The present model of home ownership also fosters a military-compound mentality, where homeowners’ primary reason to join together is to protect their most significant asset from invaders. Gated communities have become the norm, noted Mike Davis in his analysis of Los Angeles in the twentieth century: “As the walls have come down in Eastern Europe, they are being erected all over [western cities].”69 In a world where urban apartheid is fast replacing racial apartheid, those relegated to the margins cannot be expected to remain there forever.70 And if we extend our attention beyond cities such as New York, Baltimore, and London to include others like Beijing, Mumbai, Cairo, and São Paulo, the likelihood of sustaining current household dynamics seems even more absurd.

Despite the fact that today’s dizzying pace of development may seem frightening, it also offers the potential for productive change. There is no question that humans need shelter to survive, and current housing dynamics have grown out of this basic need. The human footprint on Earth has expanded dramatically over the past several centuries. Our efforts to house ourselves have proceeded in fits and starts, and they have taken different directions, depending on all manner of temporal and spatial constraints. Perhaps the realization that we could simultaneously improve our own quality of life and the environment in which we live will encourage us to experiment with some alternative ways to shape our footprint on this planet. The appropriateness of those designs will vary, however, depending on location and community preferences.

Our success depends on our determination to make maximum use of what David Harvey called humanity’s “basic repertoire” for action:

1. Competition (between people who have different interests and different positions in terms of their political power)

2. Cooperation (between people who participate in voluntary social organization and institutional arrangements)

3. Adaptation (when people respond to changes in their environment)

4. Spatial orderings (when people adapt by migrating from one place to another)

5. Temporal orderings (when people adapt by attempting to change the way processes cycle through time)

6. Transformation (when people attempt to fundamentally modify the world to suit their needs or desires)71

Harvey presents this repertoire as a summary of the human abilities urban residents should rely on when staking their claim to the cities where they live. Competition refers to the rough-and-tumble political conflicts that many may shy away from. Competition needs to be tempered by cooperation, however, if a society is to prosper. We might think of residents in a neighborhood engaging in cooperative competition as they attempt to adapt to various economic or environmental stresses, ranging from a loss of employment to water rationing. If they cannot sufficiently adapt or diversify in their current location, people may be forced to reorganize their space by migrating to another community where they can find a job. Or they may try to negotiate a delay in the due date of their next mortgage payment or their rent. If individuals are not able to cope by personal adaptations, they may even attempt the more radical stance of transforming the world around them. They could join an organization of disaffected homeowners who are refusing to leave their homes (despite being unable to meet monthly mortgage payments). If drought is the problem, they could campaign to change a neighborhood prohibition against xeriscaping. Although specific practices would vary dramatically across different communities, the above repertoire suggests a framework for the conscious integration of humans’ capabilities. It holds great promise for incrementally defusing the housing bomb—in the United States of America, the People’s Republic of China, and many other locations across the globe.