CHAPTER 2

The Evolution of Expectations and Strategies

How do rivalries de-escalate and eventually terminate? Some international relations scholars argue that these outcomes depend on favorable background conditions that encourage adversaries to believe in the settlement of their outstanding disagreements.1 Shifts in these background conditions create moments of opportunities or “ripeness” when peacemaking efforts have a chance to have positive outcomes. In other words, critical turning points occur when decision makers have the opportunity to pursue alternative strategies of conflict resolution. Which factor or combination of factors introduce critical choice points and why is left unclear.

We argue that an expectancy framework is best positioned to address these questions, because rivalries are assumed to be dynamic processes that are subject to modification in the context of environmental change. Moreover, this approach treats rivalries as protracted conflicts that are sustained by the strategies and policies of adversaries and their institutions. Over time, these strategies are reproduced in a routine fashion that produces inertia in the rivalry relationship. To modify the relationship, this inertia must somehow be overcome or upset.

Rivalries de-escalate or end when adversaries assume new interpretations, understandings, and expectations of their opponents. Such innovations can occur when environmental crises or shocks bring about the realization of other conceivable expectations. Shocks, for instance, can threaten the political survival of actors who, in an effort to secure their positions, question the viability of existing conflict patterns and repertoires of state action. Or, shocks can facilitate the rise to power of new decision makers with different expectations. As shocks hasten the reevaluation process, actors move from one set of collective understandings to another. If the direction of the shift produces negotiations, then information about these collective understandings will be exchanged through diplomacy. That is, leaders will communicate their new understandings to their opponents, and such communication will, hopefully, reinforce the process of negotiation and conciliation.

In the pages below, a model of expectancy revision is summarized and elaborated. Special attention is placed on the potential impact of shocks on altering decision makers' expectations and, ultimately, moving their strategic choices in the direction of de-escalation and rivalry termination.

A Model of Shocks, Expectancy Revision, Reciprocity/Reinforcement, and De-escalation

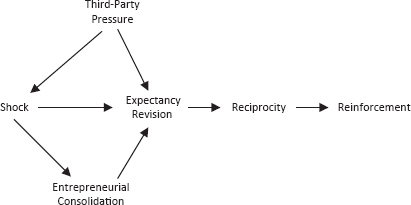

In our model expectancy revision plays a key intervening role between shocks and rivalry de-escalation and/or termination as do policy entrepreneurs, reciprocity, reinforcement, and, to a lesser extent, third-party pressure. At the core of rivalries is intransigence that results from the entrenched expectations that each side has of the other in terms of perceived intentions, tactics, and past actions. Shocks can lead to the transformation of intractable conflicts if they encourage adversaries to reevaluate their prior expectations. But there is no anticipation that shocks suffice to bring about change.

Equally important, shocks can have escalatory or de-escalatory effects. Their impacts are highly contingent on timing, context, and changes in leaders' expectations. For instance, Jervis (1997: 126) suggests that environmental stimuli that set off positive feedback at one point in time can also set off negative feedback at another as the state of a system changes. This possibility makes it difficult to posit a deterministic outcome. Consequently, shocks are at best necessary but insufficient triggers for de-escalation processes. Despite this variability, it is reasonable to hypothesize that shocks and expectancy changes are more likely to bring about de-escalation when they converge with four other variables: policy entrepreneurs who have sufficient political control to overcome internal commitments to older strategies, external third-party pressure, reciprocity, and reinforcement. The latter variables are noteworthy because they do more than just aid the initiation of de-escalation. They sustain the process through continued positive feedback.

The connections between shocks, policy entrepreneurs, reciprocity, and third-party pressure are based on the following propositions. First, actors develop strategies to deal with (internal or external) rivals on the basis of expectations concerning what other actors are likely to do and what their own capabilities to deal with rivals are likely to be. Expectations are predicated in part on what rivals have done in the past and are currently doing. Strategies, meanwhile, are plans for coping with adversaries' behavior. They are developed in response to the interpretations of an opponent's behavior, within the context of other environmental considerations (for example, other threats and opportunities, domestic coalitions, allies, capability calculations, and competing demands for resource allocation). Expectations, strategies, and behavior, thus, are not identical phenomena. One does not necessarily translate automatically into another, but the three should be related, with expectations producing changes in strategies that subsequently lead to changes in policy and behavior. During protracted conflict, as expectations among the adversaries become entrenched over time, strategies and policy actions become routinized. The result is inertia and deeper intractability. When this routine is disrupted, however, expectations, as well as strategies and actions, may be characterized by uncertainty, thereby, encouraging some actors to reorganize their previous ways of perceiving and interacting.

Second, shocks are transitional situations that can instigate a major period of change in adversarial relations by altering key expectancies. Since shocks are not always certain to alter expectancies, the extent to which they do so ultimately depends on how actors interpret them. If shocks corroborate current orientations, then actors are unlikely to adjust their strategies and actions accordingly. However, should shocks disconfirm their expectations, actors are more likely to reassess the validity of their orientations and, if necessary, abandon or revise them. This reassessment is by no means guaranteed if, for instance, actors in an effort to protect their original expectations explain away inconsistent information. In short, shocks can be transforming events only if they cause adversaries to realize that their past strategies cannot triumph or they cannot gain more by continuing them and an accommodative strategy promises to offer a better alternative (Kriesberg 1998: 217).

Shocks can be either exogenous or endogenous, although neither is assumed to have a more important impact than the other. Exogenous shocks emerge from an environment that is external to the protracted conflict (for instance, changes in the international or regional distribution of power, new threats, war), while endogenous shocks (such as economic crises) occur within the domestic contexts of the adversaries. Shocks that have the greatest impact will be those that alter how threatening the adversary appears and/or how efficacious one's own side is likely to be in coping with the adversary. The more entrenched the expectations and the deeper the strategic inertia, the stronger the shocks must be in order to tip expectations in a new direction.

Next, policy entrepreneurs on one or both sides can be crucial in bringing about de-escalation. As strategic pioneers, entrepreneurs are willing to take on and sometimes overturn policy monopolies—the dominant political understandings or orthodoxies about a policy issue—in this case, the conditions surrounding negotiations and cooperation with an adversary. Because policy monopolies are reinforced by existing institutional structures (which limit access to the policy process) and powerful supporting ideologies that reside within these institutions (Baumgartner and Jones 1993), entrepreneurs must first consolidate their political influence by effectively eliminating or removing their internal opposition and promoting the role of likeminded reformers.

Shocks can figure prominently in this entrepreneurial process. Critical events (or potentially significant transforming events) can be policy windows that allow proponents of change to assert their political leadership by advancing new alternatives to old problems. Policy entrepreneurs who favor moderation enhance their chances of implementing strategic shifts if they are able to associate hard-line policies with past foreign policy failures and convince their constituencies that learning from these failures requires a more moderate approach (Evangelista 1991).

Another consideration is the role of third-party pressure on the principal adversaries. External mediation can be helpful in bringing about de-escalation, but it is unlikely to be successful in the absence of either expectancy revision by one or both adversaries or policy entrepreneurs. Shocks may play an important role here, too. External mediators are well aware of the fact that certain periods are more propitious (or ripe) for bringing about de-escalation than others. Therefore, shocks can stimulate or renew third-party attempts in coordinating peace efforts, encouraging innovative initiatives by adversaries, providing incentives for settlements, and contributing to the implementation and durability of the agreements (Kriesberg 1998; Hartzell 1999; Walter 1999). Although third-party pressure appears to be neither a necessary factor nor a sufficient one for de-escalation, its presence in the context of an appropriate shock is more likely to reduce intractability than at other times.

Finally, reciprocity and reinforcement are essential in bringing about de-escalation (Goldstein and Freeman 1990; Lebow 1995; Goldstein et. al. 1998; Kriesberg 1998). Concessions made by one side without appropriate responses from the other side cannot be expected to contribute to a de-escalatory process. Cooperation from one's adversary reinforces the expectations about future cooperation and strengthens the shift toward moderation. Moreover, continued reciprocity between the adversaries is critical to supporting the transition process beyond the initial political breakthrough. The question is when reciprocity will bring about de-escalation. Since shocks converge with the rise of strategic innovations, the advent of policy entrepreneurs, and the renewal of external mediation, it follows that reciprocal behavior will affect de-escalation similarly.

The Theory

Our theory can be summarized in the following way. Decision makers create assumptions about their own preferred foreign policy behavior (strategies) on the basis of perceptions (expectations) of external threats, the capabilities of their enemies, and the resources available to cope with external threats. Over time, the expectations formed about external rivals become entrenched. Changing these entrenched expectations may require some combination of radical changes in the environment (shocks), new decision makers with control over their governments and less allegiance to old expectations (policy entrepreneurs who occasionally develop consolidated political positions), and encouragement from external patrons (third-party pressures). Once new strategies begin to be experimented with, intransigence upon the part of the enemy (a lack of reciprocity) and/or the failure of the new strategies to achieve a de-escalation in hostility (a lack of reinforcement) are likely to lead to an abandonment of the strategic experimentation and a relapse to earlier strategies.2

At the same time, it seems probable that none of these factors are sufficiently powerful on their own to bring about the termination of a rivalry. Subject to further analysis, we think shocks, expectational change, reciprocity, and reinforcement are absolutely essential to de-escalation. Shocks interrupt inertia or at least may do so. Without expectational change about threats and resources (their adversary's and their own), it is hard to imagine decision makers proceeding toward some type of accommodation. In the absence of any reciprocity for concessions made by one side, it is also difficult to imagine de-escalatory processes continuing for very long. For the new, less adversarial relationship to persist, reinforcement is necessary to maintain normalized interactions.

Entrepreneurs with consolidated control of their regimes are likely to be quite significant in coordinating major changes in strategy. It is even possible that they are necessary as well, but it is also possible that changes in rivalries can be attained without extraordinary leadership efforts if the shocks and environmental changes are sufficiently strong in their own right. Similarly, third-party involvement could also be facilitative, but, unlike the case for policy entrepreneurs, we are fairly sure that third parties are not necessary. In the right circumstances, rivals are fully capable of winding down their own hostile relationships.

Assumptions

We make a number of assumptions that are best stated explicitly rather than left to the reader's imagination. One assumption is that actors rarely function as unitary decision makers in pursuit of fixed national interests. Various domestic groups, including important governmental agencies, have different goals and attempt to influence governmental agendas and behavior. When feasible, groups will seek to capture their government in order to monopolize these aspects. Government leaders who wish to stay in power must attempt to juggle these internal demands within the context of external demands on governmental behavior. One of the principal ways in which this can be done is to organize and maintain a coalition of domestic groups. Maintaining a coalition requires the pursuit of interests and agendas that appeal to the coalition in question. Hence, foreign policy will reflect to variable degrees the identity of the ruling domestic coalition, assuming of course that there is one. As the identity of the coalition undergoes change, so too will the interests and agendas that are pursued.

Actors are certainly not hyperrational. They operate with imperfect information, have hazy ideas about their own values and preference schedules, and do not necessarily weigh all options and then proceed with the least costly, most advantageous alternative. Instead, foreign policy formulation and execution is likely to be a process of trial and error in which policies emerge after a number of experimental probes in different directions. Just which direction will be privileged is not always clear. However, actors in leadership positions do monitor their environment for threats and opportunities. They also attempt, variably, to respond to perceived changes in threats and opportunities.

Actors categorize other actors as either competitors or noncompetitors. Competitors are further distinguished according to whether they represent some possibility of physical attack. While noncompetitors may also be threatening, external competitors that are potential attackers are considered strategic interstate rivals. Actors develop strategies to deal with rivals (either internal or external) on the basis of expectations concerning what other actors are likely to do and what their own capabilities to deal with rivals are likely to be. As we have noted, expectations are predicated in part on what rivals have done in the past and are currently doing, and in part on what nonrivals have done and are doing. These expectations are not easy to change once they have developed because people are reluctant to revise cognitive filters for interpreting stimuli.

Given these assumptions, we can express our theory in the following propositional format:

- Actor expectations, strategies, and behavior tend to be characterized by inertia and are subject to repeated shocks of varying magnitude. In the abstract, any shock may be viewed as an opportunity for expectational and strategic revision. However, inertial constraints usually are difficult to overcome. To tip expectations (and thus strategy and behavior) from one established routine to another requires fundamental alterations in expectations.

- In turn, fundamental alterations are made more probable by major shocks that force actors to reevaluate the accuracy and appropriateness of their existing expectations and associated strategies.

- The types of shocks that have the most impact are those that alter how threatening the adversary appears and/or how efficacious one's own side is likely to be in coping with the adversary. Shocks that decrease perceived threat or the actor's own capabilities are likely to lead to reevaluation and de-escalation/termination. Shocks that increase perceived threat or the actor's own capabilities are likely to reinforce expectations and lead to intensified rivalry.

- The more entrenched the expectations are or the greater the strategic inertia is, the greater or more multiple are the shocks needed to influence expectations. No matter how great or multiple the shocks, though, there may still be variable lags between revisions in “sticky” expectations, strategies, and behavior.

- Shocks must be interpreted. The same shock may be viewed positively or negatively vis-à-vis prevailing expectations. As a consequence, a shock alone is not likely to be sufficient for expectational revisions unless the outcome of the shock completely eliminates the competitive ability of one or more adversaries.

- Possibly important are changes in leadership (for one actor or both) that go beyond mere personnel changes. New leaders, especially ones committed to developing support for new policies, may also be committed to changing external relationships and to facilitating attempts at rapprochement. To be most effective, the leadership changes must also remove or neutralize sufficiently opposition by governmental and domestic elites to revisions in expectations, strategy, and behavior. That is, they must achieve consolidation to be effective.

- Third-party pressure for revision may reduce the resistance encountered by domestic policy entrepreneurs, but it is unlikely to be successful in the absence of fundamental revisions in expectations and leadership. Third-party pressures thus may be facilitative but are unlikely to be either sufficient or necessary.

- A further necessary ingredient in the revision process is the adversary's reciprocation at some level for any initial concessions made as part of an overture toward strategic and behavioral revisions.

- Once expectations (and strategies and behavior) have tipped from one regime or routing to another (or are in the process of tipping), it cannot be assumed that the new relationship is stable. On the contrary, new relationships emerge haltingly. Consistent reinforcement of expectational revisions is necessary to prevent lapses back to the previous relationships still favored by historical conditioning.

Figure 2.1. An expectancy model for rivalry de-escalation and termination. The number of arrows shown is considered a minimal number for maintaining simplicity. Arrows might easily be drawn linking entrepreneurial consolidation and reciprocity/reinforcement. Double-headed arrows, no doubt, should be drawn in the connections among expectancy revision, reciprocity, and reinforcement. Third-party pressures might also be manifested in terms of entrepreneurial consolidation, reciprocity, and reinforcement.

Before we proceed to test this theory, sketched in outline form in Figure 2.1, something more needs to be said about delineating the shocks and other variables that are so central to our argument. We also need to consider what case or cases will best serve our theory-testing goals.

Shocks and Other Variables

The cases of rivalry termination that have been described as the easiest to explain are those involving decisive defeats, exhaustion in civil war, or voluntary surrenders due to the recognition that a competition has become too asymmetrical to continue the contest. These situations, to say the least, represent extremely strong shocks for decision makers. If the nature of the shocks is overwhelming, then the shocks can suffice to terminate rivalries. Germany's defeat in World War II in some respects represents a mixture of decisive defeat, exhaustion, and newly created asymmetry vis-à-vis its former rivals. The defeat was so complete that it ended the possibility of rivalries with the Soviet Union, the United States, and Britain—the main agents of the defeat. Interestingly, though, it did not suffice to end the possibility of the Franco-German rivalry. Whether this was due to Germany's potential for revival, France's limited role in defeating Germany, the history of oscillations in the Franco-German relative positions, the long duration of their antagonism, their geographical proximity, or some combination of these factors is not of immediate concern. The point is that even very substantial shocks do not always eliminate expectations about the probability of renewed antagonism. Even tsunami-level shocks occasionally need assistance in bringing about change. Shocks, for that matter, may well work in the opposite direction. Depending on how they are perceived, shocks can reinforce mutual hostilities—t hereby making the rivalry an even more entrenched behavioral pattern.

Clearly, shocks are critical to this interpretation. They may also be more complex than they seem at first. The main type of shock that tends to reinforce rivalry is a defeat in war that stops short of eliminating one of the two actors as a competitor. Put another way, a defeat in war may strongly suggest that one of the two actors is no longer competitive with its adversary, but this objective fact may not be internalized by decision makers on the defeated side. We have all sorts of decision-making pathologies in the foreign policy literature to explain why this large-scale misperception may occur.

The types of shock that are most pertinent to de-escalation/termination are four: shifts in external threat, changes in regime orientation/strategies, change in competitive ability, and domestic resource crises. As suggested by Figure 2.2, the four are hardly independent of one another. Rather, they tend to feed into one another. The two most straightforward types of shock are the changes to external threat and competitive ability. Decreased threat and deteriorated capability (relative or absolute) are singled out by the theory as the most potent types of changes because they go directly to the heart of rivalry expectations about threats from competitive enemies. Alterations in the perceived level of threat and/or the perceived ability to compete should (but not necessarily will) influence rivalry calculations. Nor should it be surprising to find that changes in competitiveness and threat are often reciprocal. Less competitiveness can lead to reduced threat perceptions. Reduced threat perceptions can lead to reductions in military preparations that could diminish the ability to compete militarily.

Figure 2.2. Shocks and their potential for interaction.

Changes in regime orientations or strategies can alter both the sending of threatening signals and the perception of threat by the other side. States in which foreign policies are dominated by an individual can assume a much different profile once that individual is removed from the scene. Democracies tend to respond favorably to autocracies that become more democratic. Or, in the absence of regime/personnel changes, a dramatic change in state priorities—as in reductions in militarization and foreign policy activity in favor of focusing more heavily on domestic economic development—can also affect levels of perceived threat. Similarly, domestic economic crises can both sap capability and lead to changes in strategy and regime orientation.

The strong probability of overlap in the implications of shocks is suggestive. Not only are some shock impacts likely to be more influential than other types—as the theory suggests—but the more compounding the effects are may also make some difference. The four types depicted in Figure 2.2 can work together as in a benign positive spiral of hostility de-escalation. For instance, serious economic crises and competitiveness problems might lead to changes in regime strategies and threat perceptions. But the spiral could also work in the other direction as well. A vastly improved economic resource base and increased competitiveness can encourage more ambitious foreign policies and increases in threat perceptions on the part of other states. Shocks, therefore, can be both an intermittent change in the environment and also a motor for changing international relations.

We need to be attentive to the effects of shocks and whether they occur in compounded clusters. Yet shocks are only one ingredient in the dynamic chain of linked processes sketched in Figure 2.2. The main theoretical questions are whether expectations are as critical to rivalry de-escalation processes as the theory suggests, whether shocks are needed to tip expectations, and what mix of other factors are most important to attaining rivalry termination. Reciprocity and reinforcement would seem to be absolutely critical to defusing protracted conflicts. Can the same be said of third-party pressures? Are new leaders with radical, change-seeking agendas necessary?

But what should we be looking for in terms of the other variables? Expectancy revisions are about changes in how decision makers view the adversary. By definition, rivals are seen as competitors posing sufficient threat to be branded as enemies. The revisions that we should therefore be most interested in are situations in which rivals are viewed as projecting more or less threat or becoming more or less competitive. Less threat and/or less capability, the theory suggests, should be conducive to rivalry de-escalation and termination.

A shorthand term for the type of entrepreneurial leaders that we need to be looking for does not readily come to mind. We should be alert to new leaders—new at least to the position of head of government—who come into office with the notion that fundamental change in the relationship with the adversary in question would be advantageous. The theory does not argue that established incumbents cannot entertain or initiate rapprochements. The argument, rather, is that new leaders have an edge in introducing fundamental changes in foreign policy. Established incumbents tend to be too closely linked to older expectations and strategies. Yet the advantaged leader must not only be new and committed to changing rivalry relations, she or he must also possess sufficient control of the government to overcome inertia and built-in resistance to change from within the governmental bureaucracy and the larger society in which the government operates. Thus, we are looking for new, change entrepreneurs who are also sufficiently consolidated in political terms to be able to introduce policy innovations.

Third-party pressures refer to other states that have some interest in seeing (or thwarting) a de-escalation in a rivalry. Our approach is dichotomous. It is either present or absent. Clearly, third-party pressures can be intense, mild, or something in between. Delineating how much pressure is exerted and, equally important, how continuously it is exerted goes beyond our present concerns. We are only interested in whether third-party pressures seem to be necessary—or merely part of the story from time to time.

Reciprocity means that one side's concessions are met with some form of positive response. It may be symbolic, verbal, or material. The absence of any evidence of reciprocity should doom any attempt at rapprochement. Reinforcement means that once a rivalry relationship has changed its form, both sides need to continue behaving in a nonantagonistic mode. Just how long we should insist on reinforcement is arbitrary. Short-lived de-escalations are not impressive. Extremely short-lived cooperation may be difficult to identify as indicating any real change in the relationship. Even intense rivals can cooperate on some issues. The question is whether the relationship has genuinely changed. We need some minimal benchmark. Five years of consistently altered behavior is one minimal expectation.

It is certainly conceivable that every case does not require each and every one of the six factors that we are singling out for attention. Shock, expectancy revision, and reciprocity may suffice in one instance. Shock, new policy entrepreneurs, and third-party pressures may work elsewhere. Alternatively, new policy entrepreneurs may be highly significant in one case and only marginally present in another. We need to remain open that there may be multiple pathways—as in Lebow's argument outlined in the appendix—to de-escalation. While the specific combination of factors may be variable, however, we do contend that the presence of four of the factors (shock, expectational change, reciprocity, and reinforcement) greatly increases the probability of a significant de-escalation. We do not ignore the contribution of policy entrepreneurship or third-party pressures. We think, however, that they are less contributory to rivalry de-escalation in the aggregate than our four core variables.

In summation, then, Table 2.1 provides a quick list of things to look for in our cases.

Table 2.1. Operationalizing the Expectancy Theory

Variable |

Definition and indicator |

|

Shock |

Abrupt and significant change in operating environment that is brought about by internal or external events and processes:

|

|

Expectancy revision |

Perceptions that a rival is less (more) threatening or less (more) competitive and therefore less (more) threatening; or, that one's own side is seen as less competitive vis-à-vis the rival's capabilities. |

|

Consolidated and new policy entrepreneurs |

Principal decision makers, relatively new to office, who are unusually receptive to the idea of altering external relationships. The decision makers must also consolidate their control of the government's bureaucracy sufficiently so that they can expect to overcome internal resistance to foreign policy change. |

|

Third-party pressures |

Existence of encouragement toward (away from) rapprochement by states outside the rivalry—usually restricted to major power pressures. |

|

Reciprocity |

Exchange of symbolic and material cooperation and/or positively responding to opening overtures by one side of a rivalry to the other. |

|

Reinforcement |

Once a de-escalation/termination has occurred, the rivals (former or otherwise) continue to operate more or less at the new lessened level of hostility for a period of at least five years. |

Cases

More information on how these factors have played out in specific cases is needed both to probe further the plausibility of the theory's line of argument—that is, whether we are isolating the right factors—and to see whether anything important may be missing or exaggerated. Yet there are major limitations in examining one case at a time. A general theory is unlikely to fit each and every case exactly. The question should be whether individual cases seem to approximate the general argument—with due allowance for variable weights of different factors in different cases and the possibility of different combinations of influences leading to similar outcomes.

But another problem associated with individual cases is that they have only one outcome. Either they de-escalated/terminated or they did not. Fairly static outcomes do not always help to reveal the dynamics that preceded them. Whatever the case, there is also a tendency to credit whatever seemed to precede the actual outcome with some causal efficacy. Outcome variance helps alleviate some of these problems. That is, if we have cases in which termination/de-escalation did and did not occur—or occurred to varying degrees, temporarily or seemingly permanently—we put ourselves in a better position to isolate correctly the relative role of alleged inputs to the processes at hand than if we have no variance. Of course, that is all variance does: it facilitates assessing the causal effects of multiple factors. It does not guarantee that the assessment will proceed accurately.

Variance can also become something of an analytical problem if the number of cases under investigation balloons beyond what is manageable. While manageability is always a subjective issue, the goal of probing a theory's utility suggests a more limited number of cases. More definitive tests with higher Ns can come later. The question then is how best to set up an examination with limited N and variance? One way is to look for “natural experiments.” What this means in terms of interstate rivalries is that they are often bundled in complex nests as opposed to free-standing and isolated, dyadic situations. The Middle East offers a good if very complex example. Israel has a rivalry with Egypt, but it also has or has had rivalries with Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. Egypt also has had or has rivalries with Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. Jordan and Syria have been rivals. Iraq and Iran and, probably, Syria and Iraq continue to be rivals. We could complicate this Mashriqi nest even further if we also introduced overlapping Gulf, Maghrebi, and Northeast African rivalry nests into the picture. The point here is that some regions offer outcome variance while, at the same time, help to restrict the sometimes excessive heterogeneity introduced by large N studies.

Taking on all the Middle East nested rivalries at one time would be quite a challenge in its own right. But even if we did focus exclusively on the rivalries of one region, we could never be sure that the analysis was not strongly biased by factors possibly unique to the region.3 Our preferred approach, therefore, is to work on a larger pan-Eurasian, geographical palette. We examine ten rivalries. Three are from the Middle East (or Southwest Asia) and one is from South Asia. Two are from Southeast Asia, one is from Northeast Asia, and three might best be said to be located in East Asia.

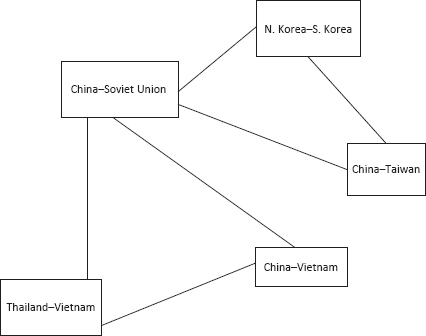

The Middle Eastern rivalries (Egypt-Israel, Israel-Palestine, and Israel-Syria) are all interrelated in the sense that what happens in one has some effect on how the other two operate. As we shall see, though, there are definite limits to their interdependencies. The six rivalries in eastern Eurasia (the two Koreas, China-U.S., China–Soviet Union, China-Taiwan, China-Vietnam, and Vietnam-Thailand) are also intertwined, and, in some respects even more closely than the Middle Eastern cases. We think it makes a good deal of sense to follow a study of the Sino-U.S. and Sino-Soviet rivalries with an examination of adjacent rivalries that seem to have been affected by the termination of the local major power feuds. In this respect, the sequential termination of major regional rivalries constituted shocks to neighboring rivalries with varied effects. One reason for these reverberations is that Russian and Chinese relations with the two Koreas, Taiwan, and Vietnam were all affected by the end of the Cold War in general, and the associated winding down of the Sino-Soviet rift.

States highly dependent on external patrons are likely to be affected heavily if the patrons lose incentives to maintain their patronage. That does not mean, however, that dependent states will react identically to such an external shock. Nor do we wish to focus exclusively on client-patron type problems—hence our examination of the two major power rivalry terminations but also the Indo-Pakistani rivalry, which certainly possesses significance in its own right but also highlights the limitations of patronage dependency. Both Pakistan and to a lesser extent India have at times been dependent on some of the actors involved in the major power triangle consisting of the United States, the Soviet Union/Russia, and China. While these dependencies have influenced the Indo-Pakistani rivalry, they do not appear to be among the most important drivers of the continuing South Asian confrontation.

As this discussion hints at, it is awkward to examine rivalries in Eurasia without giving some attention to adjacent rivalries. If their interdependencies, hinted at in Figure 2.3, demand simultaneous attention, then it is also highly beneficial that rivalries in Eurasia offer attractive rivalry outcome variance.4 One finds no change in the cases of Syria-Israel, India-Pakistan, and China-Taiwan, some varying amounts of de-escalation in the cases of Egypt-Israel, Palestine-Israel, and the Koreas, and outright terminations in the cases of China–United States, China–Soviet Union, China-Vietnam, and Thailand-Vietnam.5 The Egyptian-Israeli, Israeli-Syrian, Indo-Pakistani, and Korean cases, moreover, offer something of a variance bonus with histories of multiple attempts to de-escalate. This variance bonus nicely expands the number of cases that we can examine. Depending on how one counts, this gives us a relatively manageable set of some thirty-three cases with which to examine the expectancy theory.

Figure 2.3. Interdependencies between rivalries.

At the same time, we must acknowledge that not all the cases are fully equivalent. The complications of Egyptian-Israeli interactions make it more convenient to look at eras of different heads of government as the unit of analysis. In the Israeli-Syrian, Indo-Pakistani, and Korean cases, the cases are identified by episodes of attempted de-escalation by one or both parties within the rivalries' history. In the remaining instances, the rivalries themselves, or selected intervals, provide the boundaries delimiting the cases. We recognize the awkwardness of mixing ostensibly disparate units of analysis but think that our aggregation of these cases is defensible.

We do not give equal attention to all the rivalries examined in this study. Equal attention, from our perspective, would involve treating all rivalries exactly the same. If we examine one rivalry's full history, then we would need to do the same for the other nine. We do not proceed on this basis mainly for two reasons. One is that the ten rivalries are not equally interesting. A rivalry between China and the United States, for instance, is inherently more significant than one between Vietnam and Thailand. We can say this because a rivalry between China and the United States can have a great deal more impact than can one between two relatively small Southeast Asian states. Because of the greater potential impact of the major power rivalry, moreover, we also know more about the circumstances (or at least think we do) than we do about many minor power rivalries. Giving more weight to the big cases is thus natural.

But a second reason for giving the ten rivalries differential treatment is that we are interested primarily in end games. How do rivalries terminate? It would obviously be a great error to only examine rivalries that have ended. We very much need variance in outcomes to attempt some evaluation of what matters in rivalry de-escalation. Yet we do not necessarily need maximal variance—that is, we do not need to devote equal time and resources to the full story of every rivalry. From time to time, we can focus on episodes that might have led to de-escalation and termination but did not. We do this particularly in the Israeli-Palestinian and Korean cases, but also to a large extent in the Sino-U.S. and Sino-Soviet cases. As long as we include cases that led to termination or no change, there should be no suggestion that we are “rigging” the examination deck by exercising some selectivity in what we choose to analyze.

Nonetheless, we must remain sensitive—as should the reader—to the limitations of our approach. One good example pertains to shocks. We think shocks are highly important and we will attempt to relate them to rivalry outcomes—either as de-escalatory or escalatory—in our cases. Yet what we will continue to lack is a chronology of all the shocks experienced by decision makers. If we had such a series, then we could better estimate the association of shock with rivalry behavior. How many times did shocks occur without some change in rivalry behavior? How many times did some change in rivalry behavior occur without the occurrence of shock? Without such information, we are on shaky ground in asserting some relationship between shock and consequent behavior. Shaky ground though it may be, it will not keep us from making relationship assertions. To proceed otherwise would lead to analytical paralysis. But we and the reader need to keep in mind that more rigorous examinations in the future will be needed to nail down these asserted relationships.

Given our strong interest in the circumstances surrounding rivalry termination, it should come as no surprise that we feel no obligation to write extensive descriptions about the course of each rivalry. We are not historians. Nor are we writing rivalry histories. In several cases, very comprehensive descriptive accounts already exist. Not only do we feel no compulsion to compete with these already existing works, we have often relied upon them to assess the applicability of our own arguments.

Of course, circumstances might be even more ideal if there were less variance exhibited in the non-outcome dimensions of the cases. For instance, in terms of capability levels, we have two major-major, two major-minor, and six minor-minor power cases. Some of the actors have acquired nuclear weapons and some have not yet done so. As suggested above some actors rely or have relied on Soviet support, others on U.S. support, and still others on Chinese support. The rivalries are located in as many as five different regions or subregions. Normally, some or all of these differences might encourage considerable restraint in comparing the ten rivalries. Nonetheless, it is not clear, at least at this point in the analysis, that any of these overt differences are critical to the assessment of the theory. Should something emerge as a critical stumbling block in the subsequent comparison, one or more of the cases might have to be treated more gingerly. Yet there is no a priori reason to assume that this must be the case before any comparison or incomparability problems are encountered. To the contrary, should the theory prove relatively useful despite all of these different elements, its explanatory efficacy will have been buttressed considerably.