CHAPTER 4

The Egyptian-Israeli Rivalry, 1970–1979

If the first twenty-two years of the Egyptian-Israeli rivalry were characterized by little or no change in expectations, then the years 1971–1979 began an era of de-escalation and important shifts in this variable and the others that we stress as important. In this chapter, the expectancy model is applied in the context of two periods: the years 1971–1973, which were associated with failed peace initiatives, and the years 1974–1979, which coincided with major diplomatic agreements, such as Sinai I (1974), Sinai II (1975), the Camp David Accords (1978), and the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty (1979). Anwar Sadat emerged as a consolidated policy entrepreneur and confronted his Israeli counterpart, Golda Meir, in the years 1971–1973. Unlike Nasser, Sadat had altered his fundamental attitudes, beliefs, and expectations about the untenable nature of Egypt's rivalry relationship with Israel. On four different occasions from 1971 to 1973, Sadat extended significant peace overtures to Meir, which failed to produce Israeli reciprocity or reinforcement. At the same time, Sadat's efforts occurred without major international third-party pressure. On the Israeli side, Meir was not as formidable a presence in Israeli foreign policy as her predecessor, Ben-Gurion, had been. On the one hand, she maintained conservative beliefs about the feasibility of a diplomatic breakthrough with Sadat, despite his efforts to signal his commitment to a new direction with Israel. On the other hand, she also perceived that her government was constrained by an Israeli public that was unprepared and unwilling to make peace with Egypt even though she was aware that failure to respond to Sadat would in all likelihood result in another war (Shlaim 2001a: 289; Bar-Joseph 2006: 555).

The subsequent discussion also demonstrates that the October War of 1973 was a critical external shock that paved the way for regime changes in Israel. Meir's successors—Yitzhak Rabin and Menachem Begin—were policy entrepreneurs who revised their expectations about Egyptian behavior. Consequently, they generated the necessary diplomatic reciprocity and reinforcement that encouraged Sadat to continue diplomatic negotiations on a bilateral basis with the United States as a key third-party player in the negotiations.

Anwar Sadat and a New Perspective on the Egyptian-Israeli Rivalry

After the June War, two strains of thinking dominated Egypt's national leadership. The first school prevailed during the Nasser years while the second dominated Sadat's rule. The first view held that a political solution was unlikely and that the presence (if not the use) of a strong military force would convince the Israelis to negotiate on the basis of national security interests (Shemesh 2008: 31). The second perspective maintained that a peaceful solution could be achieved especially since the United States would encourage it as a means to reduce the Soviets' growing influence in the region. In addition, the Israelis would be willing to negotiate since negotiation would forestall another military engagement, which would be more likely in view of Egypt's recent arms buildup (Shemesh 2008: 31).

When Sadat moved into power in 1970, he decided to pursue a path that would avoid Nasser's military failures. He believed that Nasser had been overly dependent on the Soviet Union and overly antagonistic to the United States. Moreover, he believed that Nasser was unrealistic to think that Israel could be eliminated through war, because the U.S. commitment to Israel's security was unwavering and the military balance of power favored Israel over the Arabs. Therefore, he believed that the Egyptian-Israeli conflict had to be resolved ultimately through political means (Shemesh 2008: 30).

Consequently, Sadat engaged in a major shift in Egypt's relations with oil-rich, conservative, Arab governments, the United States, and the Soviet Union. He believed that the most productive way to recover territory lost to Israel in the June War was not merely to strengthen Egypt's military via the Soviet Union but to reach out to the United States in the hope that it could pressure the Israelis into negotiating an end to the conflict and the return of Egypt's occupied territories. During Nasser's funeral, Sadat met with the highest U.S. official in attendance, Elliot Richardson, and expressed his desire to move much closer to the West (Daigle 2004: 3–4). As early as October 1971, Sadat made it clear in a meeting with Secretary of State William Rogers in Cairo that he was serious about removing Soviet troops from Egypt and agreeing to a peace treaty with Israel. From Sadat's point of view, the expulsion of Soviet troops was a signal that he wanted to change U.S.-Egyptian relations and that he hoped for a more even-handed U.S. policy in the region (Daigle 2004: 7–8).

Meanwhile, Sadat sought a rapprochement with Saudi Arabia both politically and economically. Since the Saudis believed that Egypt was weak and poor in 1970, they were less threatened by Egypt's regional policies. They were also encouraged by Sadat's proclamation that he had no political or other ambitions in the Gulf region (Feiler 2003: 130). Nonetheless, the Saudis were threatened by the deepening presence of the Soviet Union in the region and, in particular, Sadat's recent friendship treaty with the Soviets, which was signed on May 27, 1971. Sadat was able to convince the Saudi government that the treaty was no more than a “piece of paper” and that his goal in signing the agreement was to ensure more military aid. Egypt and Saudi Arabia entered into a new understanding that generated increased Saudi financial aid to Egypt beyond the amounts agreed on earlier in Khartoum. Thus the “Cairo-Riyadh” axis was established.

As for the Soviets, Sadat signed that controversial friendship treaty with the Soviet Union in May 1971 largely as a result of Soviet pressure. The Soviets were alarmed by Sadat's decision to purge key pro-Soviet officials in the Egyptian government after Nasser's death and they wanted some public assurance about the strategic relationship between the two governments. Sadat complied largely because he feared that if he refused the Soviets would deprive him of essential aid and arms, weakening his domestic political position and his efforts to rebuild the Egyptian military (Beattie 2000: 86). Nonetheless, Sadat continued to pursue quiet diplomacy with both Saudi Arabia and the United States that signaled his willingness to expel the Soviets in an effort to push the peace process forward.

Sadat's Personal and Political Consolidation of Domestic Power

In addition to Egyptian's deteriorating economy, Sadat faced a major internal problem of establishing his political control over the government. At the time of Nasser's death, “centrists” who favored a close relationship with the Soviet Union and a “statist” economic approach were in control of the highest government offices. These centrists supported Sadat as president because they perceived him to be weak and someone that they could manipulate. However, Sadat was able to neutralize the police and military institutions, eliminate his political centrist opposition, and replace key officials with his own personal allies by May 1971.1 His allies were mostly rightist in orientation and skeptical of close ties with the Soviets. They were also conservative in their social and religious values, and while they were committed to maintaining the public sector they preferred a more liberal approach in the economic and political systems (Beattie 2000: 37–86).

On the foreign policy front, Sadat confronted enormous domestic pressure to retrieve the Sinai from Israel at a time when Egypt's economy was practically bankrupt. He was aware that his political survival depended heavily on his ability to bring about a change in the status of the Sinai. Because he believed that the more likely path of success was diplomacy, Sadat announced a new diplomatic initiative in search of a peace treaty with Israel from late 1970 throughout 1971.2 He never found it and by the end of 1972 he had decided on war with Israel.

Sadat's Failed Peace Overtures, 1971–1973

There were four opportunities for a diplomatic breakthrough between Egypt and Israel—all of which were initiated by Sadat to no avail. During this time, the Israeli government pursued two strategies of attrition: one was directed at maintaining the territorial status quo and the other was designed to maintain the political deadlock between Egypt and Israel, denying Egypt any political gains until it accepted Israel's terms for a settlement (Shlaim 2001a: 309).

The first signal to indicate Sadat's interest in a new direction occurred in the context of a UN diplomatic effort led by Dr. Gunnar Jarring in January 1971. Jarring proposed that Egypt enter into a peace agreement with Israel and that Israel withdraw to the former international border between Egypt and Palestine. Sadat replied that Egypt was ready to comply on the basis of UN Resolution 242, which included Israel's withdrawal from the Sinai and the Gaza Strip, a settlement resolving the Palestinian refugee problem, and the establishment of a UN peacekeeping force to maintain the peace. The overture was considered a “breakthrough” since no other Egyptian government had declared publically its willingness to sign a peace treaty. After much discussion within the Israeli cabinet, Prime Minister Golda Meir refused to withdraw to the pre-1967 borders, and much to the disappointment of Jarring and the United States, the Israeli response ended the discussion (Shlaim 2001a: 298–309).

The second signal occurred in February 1971 when Sadat proposed in a speech before his national assembly that the first step toward implementation of UN Resolution 242 could begin with the reopening of the Suez Canal and the partial withdrawal of Israeli forces from its east bank. According to Shlaim (2001a: 301–302), Sadat's initiative suggested that he was shifting the mediation from the United Nations to the United States and from an overall settlement to an interim one. Meanwhile, Egypt approached the U.S. State Department with a follow-up proposal for the feasibility of reaching a settlement to reopen the Suez Canal. Sadat hoped that U.S. pressure on Israel could break the diplomatic deadlock between the two countries.

When Prime Minister Meir responded negatively, Sadat tried again through the U.S. State Department to explain to Israel that he wanted a serious discussion via the United States, not the United Nations. Shortly thereafter in March 1971, the U.S. undersecretary of state, Joseph Sisco, presented a preliminary suggestion that Israel withdraw its forces forty kilometers from the canal, that the evacuated area be demilitarized, and that six months later the canal open to shipping, including Israel's. The resulting agreement would then be a first step toward full implementation of UN Resolution 242 with both sides reviewing the ceasefire after one year. Golda Meir was opposed in principle to the idea of Israeli withdrawal without a peace treaty. She did not like the proposed linkage between the Suez Canal agreement and the full implementation of Resolution 242, and she opposed the presence of Egyptian military soldiers on the east bank of the canal (Shlaim 2001a: 303). Nonetheless, the Israeli cabinet debated the proposal for six weeks and even presented a counterproposal. However, the internal divisions within the Israeli cabinet and the Israeli Defense Forces between dovish officials who supported an interim military withdrawal and hard-liners who did not ensured that Golda Meir's position won the day (Shlaim 2001a: 306).

Why was Meir so intransigent? According to Shlaim (2001a: 308), she feared that a partial withdrawal would lead to more pressure for complete withdrawal from the Sinai, and she believed that neither the cabinet nor the Israeli public would support such concessions to the Egyptians. Shlaim (2001a: 308) also suggests that Meir had a personal issue at stake as well: historically, she did not want to be the first prime minister of Israel to hand over territory to a major Arab rival. Ultimately, she was wedded to the “political, military and territorial status quo.”

The next major opportunity for a diplomatic breakthrough occurred in July 1972 when Sadat expelled approximately twenty thousand Soviet military advisors from Egypt without any formal settlement from Israel or promised support from the United States. Although he had several reasons for doing so, two were significant.3 One reason involved Sadat's preferences for maintaining good relations with the Saudis, who were pressuring him to force a Soviet withdrawal. Sadat was also aware that the Saudis were likely to reward his effort with more much needed financial aid (Feiler 2003: 131–132). At the same time, Sadat hoped that the forced withdrawal would lead to a renewed effort by the United States to pressure the Israelis to negotiate. Sadat viewed the expulsion as a signal of his commitment to moving closer to the West and ending the state of war with Israel (Beattie 2000: 128).

From the Israeli point of view, Sadat's move was perceived as an indication of Egypt's waning military strength and a vindication of Israel's attritional strategy of diplomacy (Shlaim 2001a: 313–314). Meanwhile, the Nixon administration offered little in return except the opening of direct channels of communication to the White House in the context of a meeting between National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger and his Egyptian counterpart, Hafez Isma'il. The meeting would eventually take place on February 25–26, 1973 and would be Sadat's last overture for a diplomatic breakthrough that would avoid war.4

The fourth case of missed opportunity occurred at the end of February 1973 during Isma'il's visit with Henry Kissinger. At this time, Isma'il offered what Sadat believed was a far-reaching proposal for a comprehensive settlement of the Egyptian-Israeli dispute. In exchange for Israeli withdrawal from Egyptian territory, Egypt was willing to commit to recognizing Israel's territorial integrity and sovereignty; to end the state of war with Israel; to extend free passage in the international waterways (for example, the Suez Canal); to accept international forces in one or two strategic points in the Sinai; and to end the boycott on third-party goods to Israel. In a second meeting in February, Isma'il also extended Egypt's commitment to prevent acts of terrorism against Israel emanating from Egyptian soil; to accept demilitarization of certain sections of the Sinai; and to proceed with normalization policies once a comprehensive settlement including the Palestinians had been reached. The Egyptians pressed for a speedy bilateral agreement and complete Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai by the end of 1973 (Bar-Joseph 2006: 548).

Kissinger defined the Egyptian proposal as “far-reaching but one-sided” and maintained that it was too close to earlier Egyptian proposals that had already produced diplomatic deadlock. In fact, Kissinger sent a personal message to Sadat saying that Sadat needed to be realistic because he was not in a position to make demands but only more concessions if the United States was to help him. As the defeated party in the negotiations and given Egypt's weak military position vis-à-vis Israel, Egypt was not in a strong position to make demands (Bar-Joseph 2006: 550–551). From Kissinger's perspective, Egypt would not be able to change this strategic reality and with time it would have to make more concessions. Kissinger was wrong. After these meetings, Sadat concluded that a military initiative was the only solution to breaking the deadlock, and by April 1973 Sadat had formed a war cabinet and drawn up war plans with Syria (Beattie 2000: 131; Sela 2000: 47).

Meanwhile, Golda Meir, in her visit with Nixon in March 1973, conveyed her satisfaction with the lack of diplomatic progress and made a concerted effort to secure more U.S. military aid for Israel. She explained that as time passed Israel's control over the occupied territories would eventually be accepted by the international community. She also perceived that Israel's military defense was “impregnable,” which meant there was no need for diplomatic change (Shlaim 2001a: 314–315). Essentially, Israel's primary goal in 1972–1973 was to pursue a “diplomatic strategy of attrition”: perpetuate the status quo, sustain the political deadlock, and deny the Arabs any political gains until they accepted Israel's terms for a settlement (Shlaim 2001a: 315). Meir and her cabinet stuck to this strategy although they had warnings that Egypt was preparing for war as early as April 1973. Meir and her advisors failed to act diplomatically to avert the coming war (Bar-Joseph 2006: 552–553).

The question remains about how Sadat was able to finance another military confrontation with Israel at a time when the Soviets were backing away from military aid. Sadat's rapprochement with the oil-rich Arab governments played a significant role. In short, Sadat was able to secure additional financial support—without which he would not have been able to launch a war (Feiler 2003: 135). For instance, in mid-December 1972 after Sadat's expulsion of Soviet advisors, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Libya pledged to provide Egypt with a substantial amount of military and financial assistance to be used to purchase arms from the Soviets. From January 1973 to October 1973 when the war began, these Arab governments continued to provide substantial financial support for buying arms, and by October 1973, King Faysal of Saudi Arabia had agreed to an oil boycott in the eventuality of an attack by Egypt against Israel (Feiler 2003: 134).

By the fall of 1973, after six years of war preparation, Sadat had run out of time. At the end of the year, international debt payments had to be met, and Sadat knew that he could not repay them. In addition, substantial domestic unrest began to emerge as students and workers began demonstrating for the end of a military postponement to the Sinai issue (Beattie 2000: 133). Therefore, Sadat changed his military objectives from liberating the Sinai totally from the Israelis as had been planned in 1972 to fighting a limited war for the east bank in the Sinai in 1973. Sadat wanted to achieve a complete strategic surprise early in the war so that his army had time to cross the Suez Canal and grab at least “10 centimeters” of the Sinai. At that point, the superpowers would intervene, establish a ceasefire, and begin a diplomatic process that would end the political stalemate (Sela 2000: 57). Following the conclusion of a new arms deal with the Soviets in late August 1973, Sadat finalized his military plans with President Asad of Syria for a coordinated attack and both agreed to launch the war on October 6, 1973.

The Impact of the October War of 1973: A Shift in Sadat's Strategy and Rabin's Moderation

In the aftermath of the war, Sadat's popularity among the Egyptian public soared as a result of the army's initial success in crossing the canal despite Israel's encirclement of Egypt's Third Army outside Cairo and the intervention of the superpowers to prevent Egypt's military defeat. The “crossing” strengthened Sadat's position domestically, providing him with the space to pursue new domestic and foreign policies. Since he had few economic resources left after the war, Sadat aggressively pursued a peace agreement with the Israelis. Such an agreement would allow him to rechannel money from the military to the economy and regain Egypt's three primary sources of revenue: the Suez Canal, the oil fields of the Sinai, and tourism (Barnett 1992: 129).

In order to achieve such an agreement, Sadat significantly changed his political strategy. First, he sought a negotiated solution with Israel by breaking solidarity with Syria and other Arab confrontation states that maintained a rejectionist stance. Before 1973, Sadat supported a collective Arab effort at securing a comprehensive peace agreement with Israel, but after the war he followed an independent course of action. Moreover, he did so by securing the mediation efforts of the United States, which was better positioned than the Soviet Union to bring about such an outcome. Sadat believed that the Soviet Union was a “second-rate power” with poor technology, while the United States was the “only” superpower that could help him solve Egypt's economic problems and achieve peace with Israel. Therefore, he relied on U.S. mediators, particularly Kissinger, in influencing Israel to negotiate a withdrawal from the Sinai (Beattie 2000: 147–148).

Shifting Egypt's allegiance from the Soviet Union to the United States also served another purpose as well. Sadat hoped to enlist U.S. aid to finance his economic liberalization program at home. The new program, called “al-infitah” (the opening), was launched in 1974 and designed to open Egypt's economy, encourage foreign and domestic capitalist investment, and support private capitalist development—all of which hopefully would rectify Egypt's lack of economic growth, its growing foreign debt, its balance-of-payment crisis, and its depleted foreign exchange reserves (Barnett 1992: 131). Sadat hoped to attract foreign capital and private foreign investment that would lead to new employment opportunities in foreign companies and joint ventures with Egypt's public sector firms. These joint ventures would invigorate Egypt's firms with an infusion of new technologies, capital and management techniques, and a more competitive edge (Beattie 2000: 146).

Sadat knew that if “al-infitah” was to succeed he had to improve relations with those countries whose foreign capital he needed most, in particular, capital from oil-rich countries of the Middle East and North Africa and from the developed countries in the West. If his economic strategy was to work, then Sadat had to convince foreign investors that their investments would be profitable but also safe from destruction in another Middle East war. Therefore, securing peace with Israel became a vital part of Sadat's economic strategy (Beattie 2000: 147). Sadat's strategic shifts in foreign policy, in short, were linked inextricably with his economic reforms at home.

These shifts in foreign and economic policy explain Sadat's willingness to sign two major agreements with the Israelis and terminate Egypt's ties with the Soviets. In January 1974, as a result of U.S. mediation, Sadat signed a disengagement agreement (Sinai I), which required Israel to withdraw from territory on the western and eastern sides of the Suez Canal, which would then became separate buffer zones for Egyptian, Israeli, and UN troops. The agreement also acknowledged that the disengagement was the first step toward a lasting peace in accordance with UN Resolutions 242 and 338. In September 1975, again largely as a result of U.S. mediation, Sadat signed the Sinai II agreement with Israel, which resolved to withdraw from the oil fields on the Suez Canal and the Mitla and Giddi passes in exchange for a U.S. built early-warning station to be operated by U.S. troops.5

Lastly, Sadat abrogated the Egyptian-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation six months later in March 1976. Sadat's decision to distance himself from the Soviets reflected his concern about Egypt's growing trade dependence on the Soviets for military imports in exchange for Egyptian exports. Such dependence precluded the opportunity of exchanging Egyptian exports for Western technology and inhibited economic growth. Sadat believed that Western technology, Arab petrodollars, and access to international economic institutions such as the International Monetary Fund could deliver the necessary resources to aid Egypt's economic woes. Moreover, not only was the United States positioned to provide access to Western technology and aid, but it was also more likely to bring about peace between Egypt and Israel through its mediation. Hence, Sadat no longer viewed the Soviet Union's economic model or its financial aid to be viable (Barnett 1992: 134).

Sadat's strategy paid off handsomely. In 1975, the United States provided $372 million with approximately $111 million allocated for food aid. After Egypt abrogated the Egyptian-Soviet Friendship Treaty in 1976, U.S. economic assistance escalated to $987 million with $192 million designated as food aid (Beattie 2000: 179). Moreover, the influx of aid from oil-rich Arab states, Japan, and international economic institutions exceeded debt amortization payments by almost $2 billion in 1975 (Beattie 2000: 149). New income also emerged from the opening of the Suez Canal, the Sinai oil fields, tourism, and increased foreign remittances. Sadat's new orientation to the West contributed to new domestic economic wealth and temporarily solved Egypt's liquidity problems.

On the Israeli front, the October War of 1973 weakened the public's support for the Labor-led government. Prime Minister Golda Meir eventually resigned in April 1974 over her handling of national security issues and in particular her government's failure to entertain and detect the possibility that Egypt and Syria would cooperate in a surprise attack against Israel.

Although the Labor Party continued to govern through Yitzhak Rabin's leadership, it was wracked with internal divisions and the loss of its rank-and-file members to conservative and right-wing parties. Rabin and the Labor Party also faced serious economic problems. The costs of the war (that is, one year's GNP) and the increase in oil prices in the wake of the Arab oil embargo produced a decline in economic growth. For instance, Israel's economic growth rates varied between 11.2 percent and 9.7 percent in the 1950s and 1960s. Between 1973 and 1980, however, those rates decreased to 3.2 percent. Meanwhile, the defense burden surged dramatically after the war to as much as 28 percent of the GDP (or 16 percent subtracting U.S. aid and other external aid) (Y. Levy 1997: 146). Concurrently, in 19741975 global inflation associated with the oil embargo increased Israel's balance-of-payments deficits to $3–4 billion from their typical level of $500,000 to $1 billion before 1973, and Israel's national debt escalated from $980 million in 1965 to more than $9 billion in 1978 (Crittenden 1979: 1007).

As Israel became more dependent on the United States to cover its growing defense burden (as much as 40 percent of its defense budget) and balance-of-payments deficits, the Labor government increased national taxes, cut subsidies, and devalued the Israeli pound (Crittenden 1979: 1007; Y. Levy 1997: 146). These austerity measures eroded Rabin's public support among the lower classes, who were becoming attracted to more conservative and religious parties (Barnett 1992: 189).

In addition to Israel's economic woes, Rabin's government was weak, vulnerable to internal disputes, and cautious about its foreign policy. Rabin, himself, advocated an ambiguous policy based on “continuity and change” and he was evasive about what territorial compromises he would be willing to make to secure peace with Egypt. He preferred moving slowly, playing for more time when Israel would be economically and militarily stronger. He refused to allow Egypt and other Arabs to believe that Israel would make concessions from a position of weakness (Shlaim 2001a: 326–327). So, Rabin pursued a “wait and see” approach, demanding that a second disengagement agreement be premised on the principle of reciprocity; that is, that Egypt end its state of belligerence as a precondition for Israel's withdrawal from parts of the Sinai. Sadat, of course, refused to make any such formal announcement, and even Kissinger, who was mediating the terms of what would eventually be the principles of the Sinai II agreement, argued that Israel's position was unreasonable (Ben-Zvi 1993: 94).

At this point, the United States played a critical role in influencing Rabin to accept a more modest plan restricted to a unilateral military withdrawal from parts of the Sinai. In compensation for this concession, President Ford and Secretary of State Kissinger signed a “memo of understanding” that committed the United States to be responsive to Israel's military, economic, and energy demands. In other words, the United States agreed to provide large-scale economic and military aid (approximately $1.5 billion in military credits, plus about half that amount in economic aid for the following year), and advanced weapons. In addition, the United States made commitments to protect Israel from other major power threats, supply oil if it should be denied access, refurbish it with more advanced weapons over time, maintain the U.S. policy of nonrecognition toward the PLO, and consult closely with Israel on any future Middle East proposals (Ben-Zvi 1993: 101–102). The cost of the agreement to the United States was approximately $4 billion annually for the next three years, or 200 percent above the existing level of U.S. aid to Israel (Shlaim 2001a: 338). In return for relinquishing one-seventh of the Egyptian territory along the Suez, including the strategic passes and oil fields, Rabin gained breathing space to rebuild Israel's military capabilities, deepen the U.S.-Israeli relationship and negotiate a deal that was independent of a comprehensive Middle East peace agreement involving Syria and Jordan.

In sum, the October War exacted enormous costs on both the Egyptian and Israeli economies. Six years of war preparation left Sadat with a debt-ridden economy that required a rapid infusion of aid and investment. Discarding his alliance with the Soviets and striking out on his own, Sadat sought U.S. diplomatic and economic aid in securing two major disengagement agreements with the Israelis. The October War, in turn, increased Israel's economic vulnerability and its dependence on the United States for external aid. Consequently, after much pressure from the United States, Rabin participated in the Sinai agreements, but only after he had obtained strong commitments from the United States to provide aid, arms, and diplomatic support in the future. Although Sadat's reorientation of his foreign policy played a key role achieving the Sinai I and Sinai II agreements, Sadat's success is due largely to the active mediation role of the United States and its economic and military largess to both Egypt and Israel.

Economic and Political Pressures Prior to 1978

Egypt and the Food Riots of January 1977

Although economic liberalization improved Egypt's economy, foreign debt levels accelerated from 1973 to 1976 and government subsidies increased more than thirteen-fold (Beattie 2000: 207). In fact, government borrowing in 1975 had tripled that of 1973 and constituted almost one-third of the GDP (Karawan 2005: 329). By 1977, the foreign debt was $12.2 billion; $2.1 billion in short-term loans with high interest rates, $2.5 billion in Arab financial deposits, $3.4 billion in long-term loans, and $4.2 billion from Eastern Europe. Debt servicing made up 50 percent of Egypt's export revenues, and including the military debt it amounted to 70 percent (Karawan 2005: 329).

The debt levels made it increasingly difficult to get new lines of credit especially from the Arab oil-producing countries, which began to dissociate themselves publically from Sadat's government, especially after the Sinai II agreement.6 Refusing to commit to an “Arab Marshall Plan,” the Gulf states tied any future financial aid to Egypt's commitment to undertake austerity reforms recommended by the International Monetary Fund (Feiler 2003: 138). One of these austerity measures involved the cutting of government subsidies, which constituted 33.6 percent of government spending in 1976 (Waterbury 1983: 214). In light of the pressures from the International Monetary Fund and Egypt's creditors, Egyptian officials reduced subsidies on thirty commodities, which in turn generated increased prices for basic foodstuffs. (Beattie 2000: 208; Rivlin and Even 2004: 42). The increase would have cut the purchasing power of about 30 percent of the population by 25 percent or more and triggered an avalanche of other price increases that would have raised the costs of living beyond the means of urban dwellers (Karawan 2005: 330). Immediately, the government's decision generated two days of violent protests and demonstrations by industrial workers, government employees, pension recipients, and the urban poor. At least fifty to seventy-nine people were killed with another six hundred to eight hundred wounded by the time the government rescinded its austerity measures three days later (Beattie 2000: 208; Rivlin and Even 2004: 42).

After the riots, government expenditures on subsidies continued to rise. By 1979, these expenditures had increased to 1.27 billion Egyptian pounds (about $1.85 billion), constituting almost 20 percent of the national budget in that year (Rivlin and Even 2004: 42).7 Meanwhile, government spending on the military stayed at the same levels from 1973 to 1977, and in 1976 constituted as much as 37 percent of the GNP. According to one estimate, Egypt spent three times the amount on arms from 1975 to 1981 as it had in the previous twenty years (Barnett 1992: 130).8 Consequently, Egypt was trying to meet social welfare, development, and defense needs at a time when its revenue base was not expanding rapidly enough.

The riots and demonstrations in January 1977 revealed the depth of unrest in urban districts all over Egypt. Sadat was aware that the government's policies were generating deep grievances among Egypt's urban poor and stimulating the mobilization of Islamist, Nasserite, and leftist opposition groups. After the riots, Sadat designated 1977 as the “year of settlement” with the Israelis. The increasing political stalemate between Egypt and Israel since the Sinai II agreement was unbearable for Sadat, who desperately wanted a final agreement that would restore Egypt's access to revenues from the Suez Canal and tourism as well as link the country to Western foreign aid and investment. Rather than asking the Egyptian public to suffer from economic belt-tightening policies, Sadat perceived that the easier, safer alternative was to look for international sources of financing which could be obtained only with a final peace agreement with Israel (Beattie 2000; Barnett 1992).

Thus, Sadat embarked on his famous trip to Jerusalem in November 1977 at time when he believed that there was no alternative to achieving peace with Israel. By speaking in front of the Knesset, Sadat conveyed his implicit recognition of Israel's sovereign legitimacy in the Middle East and signaled a significant change in Egypt's foreign policy. Sadat made this overture because he desperately needed a peaceful resolution so that Egypt could receive the material, factories, and food, quickly and cheaply on predictable terms, in order to revitalize his economy. He believed that the United States and the West could meet these needs and the loss of Arab support in the context of a major peace agreement with Israel was less significant (Stein 1993: 86).

Israel, the National Election in 1977, and Begin

The Likud Party's victory in the parliamentary election in May 1977 ejected the Labor Party from office for the first time in Israel's history. Leading the Likud Party, Menachem Begin emerged as prime minister after piecing together a narrow right-wing coalition of conservative and religious parties. Begin's foreign policy priorities differed significantly from those of the previous Labor governments, particularly on the issue of the occupied territories. Although he was keen on continuing Labor's search for a peace agreement in the Middle East, Begin was unwilling to negotiate any deal that relinquished Israel's hold on the occupied territories. Begin and the Likud Party were ideologically committed to the notion that the West Bank and the Gaza Strip belonged under Jewish control. Shortly after forming his new government, Begin pledged to build Jewish settlements in these areas, although he had no immediate plan of annexing them.

Begin's foreign policy strategy rested on achieving a peace agreement with Egypt in order to remove it as a rival and ensure peace on one of its borders. However, he was unwilling to exchange any territory outside of the Sinai Peninsula. What Begin sought was not so much an exchange of Sinai territory for nonbelligerency but an exchange based on Israel's continued control over the West Bank through a proposed Palestinian autonomy plan that would be endorsed by both Egypt and the United States (Sachar 1981: 258; Shlaim 2001a: 362).

Shortly after his election, Begin pursued the option of a bilateral agreement with Egypt by secretly signaling Sadat that Israel was interested in direct peace talks. Choosing to ignore the multilateral talks cosponsored by the United States and the Soviet Union at the Geneva Peace Conference, Sadat announced on November 9, 1977, his willingness to travel directly to Israel to negotiate a peace deal that would return the Sinai to Egyptian sovereignty. In addition, he reiterated his position that he wanted a comprehensive peace that would lead to Israel's full withdrawal to the borders of 1967 and Israel's recognition of the Palestinians' right to sovereignty. Four days later, Begin invited Sadat to Jerusalem to conduct talks that would hopefully culminate in a permanent peace between both countries.

During Sadat's visit to Jerusalem, Sadat and Begin agreed to three principles: the rejection of war between the two countries; the formal restoration of Egyptian sovereignty over the Sinai Peninsula; and the demilitarization of most of the Sinai, with a limited Egyptian military presence in the area adjoining the Suez Canal, including the Mitla and Gidi passes (Sachar 1981: 267; Shlaim 2001a: 361). Sadat's demands for total Israeli withdrawal and Palestinian recognition were unresolved.

Begin's strategy can be understood in the context of three internal pressures—two of which emanated from domestic constituencies. Gush Emunim (“Bloc of the Faithful”) emerged soon after the October War in 1974 as a political movement of young, fundamentalist Israelis who demanded that Israeli law and Jewish settlements be established in the West Bank. Its members staged protest demonstrations that included illegal Jewish settlements in the occupied territories, violent attacks on local Palestinians, and opposition to any significant peace negotiations with Egypt. Despite their radical tactics, Gush Emunim's interests were represented in all the secular and religious parties of the right in Israeli politics—the very groups with whom Rabin formed a government after the national election in 1977. In fact, Begin and the Likud Party were especially supportive of and sympathetic to Gush Emunim's demands that Judea and Samaria remain in Israel's permanent control regardless of Palestinian claims, which explains Begin's unwillingness to negotiate with Sadat on the future of the occupied territories (Y. Levy 1997: 156).

In addition to Gush Emunim, the Peace Now movement, composed initially of retired military officers, appeared in 1978 and soon expanded to include academics, professionals, and semi-professionals. Peace Now activists mobilized in order to put greater pressure on Begin to advance a peace agreement with Egypt that involved territorial compromises. In addition, Peace Now opposed the expansion of Jewish settlements in the occupied territories. Throughout the spring and summer of 1978, activists organized massive demonstrations, met with government and party officials, and arranged media campaigns to maintain the pressure on Begin and his government. On September 12, 1978, the day before Begin left for Camp David and direct talks with Egypt, Peace Now activists, numbering over one hundred thousand citizens, marched on Tel Aviv's town hall, pushing Begin to make the necessary concessions to achieve a peace treaty (Bar-On 1996: 112).

Another important factor influencing Begin's strategy was Israel's deteriorating economy, especially the problems associated with the increasing balance-of-payments deficit, growing hyperinflation, and rising economic dependence on U.S. aid. Begin pursued an economic liberalization policy, which loosened controls over foreign currency, allowing the Israeli pound to find its own level in the foreign exchange market. In addition, Begin slashed export subsidies and reduced subsidies on basic commodities. His reforms were intended to attract foreign investment, encourage capital flows back into Israel, force Israeli industry to be more competitive without domestic protection, and stimulate the sale of Israeli goods abroad through the devaluation of the Israeli pound. Begin surmised that if the plan worked, Israel's economy would not need the $1 billion of U.S. aid that it had been receiving since 1975 (Crittenden 1979: 1007–1009).

Largely due to Begin's unwillingness to cut defense-related expenditures or social and welfare services, these reforms, along with the rising national debt, brought about spiraling inflation. By 1985, inflation stood at an annual rate of 400 percent (Y. Levy 1997: 147). Consequently, Israel's dependence on the U.S. aid had increased dramatically. For instance, in the five years after the October War of 1973, the United States transferred more than $10 billion in official assistance (Crittenden 1979: 1013). This aid made it possible for Israel to avoid raising taxes and diverting civilian expenditures. In addition, it helped Israel deal with its national debt, pay off its war losses, and cope with the increasing costs of energy following the Arab oil boycott after the October War. In short, Israel's external dependence meant that U.S. aid was critical to maintaining Israel's standard of living, beyond the military weapons that the United States provided (Y. Levy 1997: 148). Increasing dependence on the United States, however, meant that Begin was highly sensitive to maintaining good relations with President Jimmy Carter, who was pressuring him to make significant concessions on both the Sinai and the Palestinian territories.

U.S. Mediation and the Camp David Accords of 1978

In the year preceding the Camp David meetings in September 1978, the negotiations between Egypt and Israel reached a stalemate. The knottiest issue centered on Sadat's demands for full restoration of the Sinai and national self-determination for the Palestinians. Begin countered with a Palestinian autonomy plan that would involve self-government for the West Bank and the Gaza Strip while Israel maintained internal security. After a five-year interim period, Israel would review the situation. Angry about the recent construction of Israeli settlements in Rafah (Sinai), the Egyptians demanded total Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai, full Palestinian sovereignty, and no separate peace agreement (Shlaim 2001a: 364–367).

In August 1978, President Carter invited Begin and Sadat to attend a summit meeting at Camp David. Both leaders accepted the invitation without any preconditions. When Carter, Begin, and Sadat arrived at Camp David, the focus centered on a bilateral peace agreement dealing with the normalization of Egyptian-Israeli relations, the removal of Israeli settlements in the Sinai, the scope of the demilitarization of the Sinai, and an agreement on a general principle on the right to Palestinian self-determination and a linkage between normalization and the future of the Palestinians (Stein 1993: 87–88).

Stein (1993: 89) argues that at this point Begin and Sadat were aware of the major political costs they would incur if they emerged from Camp David without an agreement. Sadat needed Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai in order to be able to address the economic problems in Egypt. The economic costs were not as dire for Begin, but he was conscious of the necessity of maintaining good relations with the United States. Begin knew that maintaining good economic and political support from the United States was critical for Israel because of its isolation in the international community and its dependence on U.S. aid (Stein 1993: 89). Similarly, Sadat was not immune to Carter's warnings that if Sadat left Camp David without securing an agreement he could lose U.S. support as well, in particular, its aid, investment, technology, and continued diplomatic pressure on Israel. Therefore, Carter was able to move both Begin and Sadat to accept two frameworks for peace after thirteen days of intense negotiations.

The negotiations at Camp David ended at the White House with the signing of the Camp David Accords on September 17, 1978. The success at Camp David was largely due to Carter's dogged determination to see the negotiations conclude successfully. Without his involvement and his efforts to reconcile Begin's and Sadat's negotiating positions, the Camp David Accords would not have been signed. Begin and Sadat were also aware that walking away from the negotiations would assure them of being blamed for the failure, of disappointing a U.S. president, and consequently, of ensuring a less than friendly relationship with United States in the future (Stein 1999: 252).

The Camp David Accords were not so much a treaty as a promise of two negotiating tracks: one dealing with the future of the Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip and the other relating to the Egyptian-Israeli agreements on the Sinai. In the coming year, the framework for Palestinian sovereignty or autonomy would not come to fruition. However, the second framework laid the groundwork for the Egyptian-Israeli treaty that would be signed by Begin and Sadat six months later in March 1979. At Camp David in 1978, the Israelis agreed to a full withdrawal from the Sinai, including the evacuation of Israeli citizens in the area within three years and the return of the oil fields in the western Sinai. In return, Egypt would restore normal diplomatic relations with Israel, guarantee free passage through the Suez Canal, and restrict the number of its forces along areas close to Israeli borders. Both Sadat and Begin were able to consolidate their governments' ratification of the treaty without much opposition due to their relative autonomy within their governments. While Sadat had a strong autocratic control over his political environment, Begin was the undisputable leader of the Likud Party and was able to rally domestic support for his diplomacy (Stein 1993: 93).

The agreements of 1978 and 1979 also resulted in the United States committing several billion dollars worth of annual subsidies to both Egypt and Israel, much of which continue to this day. The United States provided a total of $7.5 billion to both Egypt and Israel in 1979 (Sharp 2009: 19). Egypt also received assistance from the World Bank, West Germany, and Japan in exchange for the political agreement. Their aid totaled $1 billion in 1979, and in the same year Western businessmen invested about $500 million in the Egyptian economy (Feiler 2003: 212).

The Application of the Expectancy Revision Model of Rivalry De-escalation

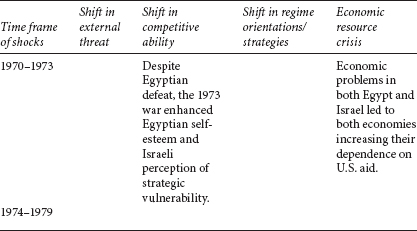

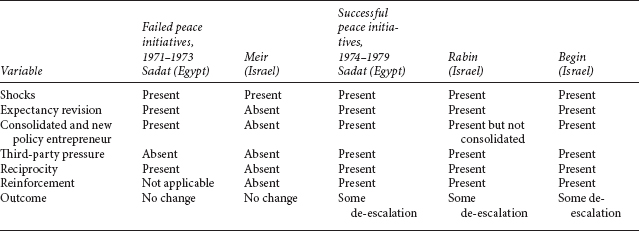

Table 4.1 shows the critical variation in the model's variables. In the first period of Sadat's peace initiatives, the absence of all but two of the six independent variables accounts for the lack of rivalry de-escalation. In contrast, the post-1973 era is associated with the presence of five of the six variables of our model across the administrations of Sadat, Meir, Rabin, and Begin and explains the de-escalation of the rivalry.

War shocks played a considerable role in changing the attitudes and expectations for Anwar Sadat, Yitzhak Rabin, and Menachem Begin, but not for Golda Meir. Sadat's expectations for peace changed after the June War in 1967, but it would take another war with Israel in 1973 before the expectations of Rabin and Begin would also change.

Table 4.1. Modeling Outcomes for the Egyptian-Israeli Rivalry, 1970–1979

Sadat's expectational shifts are discernible in the aftermath of the war in 1967. The war diminished Egypt's regional role, but more significantly, it pushed Egypt to the edge of financial bankruptcy. As a consequence, Sadat sought to link the restoration of Egypt's deteriorating economy with the termination of hostilities with Israel. Sadat believed that securing a peace treaty with Israel would lead to a recovery of lost government revenues from the Suez Canal and also open the door to new sources of economic aid, technology, and investment from the United States and Western Europe.

While the June War had less effect on changing Israeli expectations about peace with Egypt, the October War had considerable impacts on both Rabin and Begin. Rabin signed the Sinai I and Sinai II disengagement agreements, the latter of which laid the foundation for the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty of 1979. Nonetheless, Rabin's attitudes and expectations about Egypt had not changed so dramatically that he viewed these agreements as irrevocable steps to a final peace agreement with Egypt. Rabin's moderation from 1974 to 1977 stemmed from his desire to consolidate Egypt's new pro-U.S. orientation, to place a wedge between Egypt and Syria in order to eliminate a future threat of a two-pronged war against Israel, and to maintain good relations with the United States, which pressured him to commit to these agreements (Inbar 1999: 21).

Rabin's successor, Menachem Begin, also saw the merits of negotiating a peace settlement with Egypt in the aftermath of the October War for the purpose of removing a significant rival on one of Israel's borders. However, he was willing to do so only under terms that would ensure Israel's continued control over the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Begin's perceptions were shaped by his recognition of the necessity of maintaining good relations with the United States at a time when Israel was becoming more and more economically and militarily dependent on it. Faced with a deteriorating economy, international pressure from the United States, a mobilized Peace Now Movement that advocated for a treaty with Egypt, and a highly mobilized settler movement that demanded permanent access to the West Bank, Begin negotiated a peace treaty with Egypt in 1979 largely on Israel's terms.

From 1971 to 1979, Sadat was a policy entrepreneur who was able to advance his new foreign policy goals by consolidating his political control inside and outside of his government. On the Israeli side, however, Golda Meir was neither a policy innovator nor one who had established complete control over her cabinet. Rabin was an innovator in that he was willing to pursue peace negotiations with Egypt, but he was constrained by a divided cabinet and domestic public opinion that was shifting in a more conservative direction. Hence, Rabin was cautious and unwilling to take dramatic steps toward peace with Egypt. Begin, in contrast, exhibited both traits (Stein 1993: 91). He was willing to move in a more controversial direction by signing the Camp David Accords in 1978 because of his personal and political control over the Likud Party, which dominated his cabinet, and his ability to mobilize support in the Knesset. Begin successfully stitched together a coalition of support from within the Likud and the Labor parties to gain a majority of the votes in the Knesset for ratification of the accords. Begin also enjoyed widespread public support for the accords as well (Shlaim 2001a: 377). In 1979, Begin achieved the ratification of the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty with even more support from the Knesset.

With the exception of Golda Meir in the years 1971–1973, there were many cases of reciprocity and reinforcement between Sadat and the Israeli prime ministers. During the years 1971–1973, Sadat initiated a series of overtures on four different occasions—all of which were rebuffed by Meir. However, after the October War, renewed efforts by Sadat to convey his serious intentions to end Egyptian hostility were received in a more positive manner by both Rabin and Begin. The step-by-step or graduated peace negotiations between Egypt and Israel, which were mediated by Kissinger between 1973 and 1975, created room for reciprocity and reinforcement to lay the groundwork for the agreements in 1978 and 1979. Probably, the most dramatic and obvious effort to signal such intentions was Sadat's visit to Jerusalem and his talk before the Knesset in 1977. This event was well received within Israel and paved the way for Begin's commitment to enter negotiations with the United States and Egypt at Camp David.

Mediation by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger during the years 1973–1975 and President Jimmy Carter in the years 1978–1979 were critical to the de-escalation process. At the end of the October War in 1973, Kissinger negotiated a series of partial agreements that first resulted in a disengagement of Egyptian and Israeli military forces in 1974; in 1975 Kissinger negotiated a broader agreement that led to the withdrawal of Israeli forces from strategic areas in the Sinai in exchange for a nonbelligerency pact from Egypt. This agreement was the first time that Israel had agreed to a significant withdrawal of forces since the June War of 1967 and the first time that an Arab leader supported a nonbelligerency agreement (Stein 1985: 332).

In 1978–1979, Carter pursed a similar mediating style. He negotiated bilaterally with Israel and Egypt directly and then used those discussions to forge an agreement between Israel and Egypt.

The United States was successful in negotiating these agreements for several reasons. First, the United States acted as a guarantor of the observance of the treaty to both sides, thereby reducing the risks of concessions (Touval 1982: 225–320). For instance, during Kissinger's negotiations, the United States offered to intervene and consult as to appropriate action should one of the parties violate their agreements. The United States also promised Israel that it would veto any UN Security Council resolution that would adversely affect the agreement. Kissinger also committed the United States to providing aerial reconnaissance of the demilitarized zones in the Sinai and transmitting the data to both sides (Stein 1985: 343).

Similarly, Carter also promised to guarantee that both parties would observe the treaty. Carter went so far as to promise that the United States would consult with Congress in the event that there was a violation of the treaty and that it would take appropriate actions to ensure compliance with the treaty. Moreover, the United States promised to support appropriate actions by Israel should the treaty be violated and to oppose any UN resolution that could adversely affect the treaty. Like Kissinger, Carter also committed the United States to monitoring the implementation of the limitation of force arrangements and to transmit the information to both sides (Stein 1985: 343).

Another reason that U.S. mediation helped to bring about the de-escalation of the Egyptian-Israeli rivalry is the role that the United States was willing to play as a “benefactor extraordinaire” by committing significant amounts of long-term economic and military aid to Egypt and Israel. Hence, Kissinger and Carter were willing to “guarantee, insure and reward” both countries if their leaders were willing to make concessions. The United States also acted coercively by threatening the loss of good future relations should one or both parties be unwilling to make important concessions that would produce an agreement. Hence, the United States had enormous bargaining leverage over the participants. Of course, U.S. mediation was successful because it was timed with the rise of Egyptian and Israel leaders who were pessimistic about the benefits that were or could be derived from past or future conflict. In sum, Sadat, Rabin, and Begin considered military force to be an unappealing option because of the increasing domestic political and economic strains associated with each war. As Stein (1985: 345) argues, “Their estimates of likely economic and military loss, of adverse political consequences at home, and continued military tension were critical” in redefining the parameters of the Egyptian-Israeli rivalry. Despite the skill, motivation, persistence, coercive pressure, and wealth of the United States, Kissinger and Carter would not have been able to accelerate the de-escalation process without a significant prior reorientation of the strategic thinking of the key actors.

The expectancy model of rivalry de-escalation brings together six critical variables that worked together to bring about the rethinking of political leaders involved in an intense rivalry. In the years 1952–1970, with the exception of internal and external shocks, none of the remaining variables lined up on both sides of the rivalry. So, the presence of shocks alone is neither a necessary condition nor a sufficient one for the de-escalation of a rivalry. The years 1971–1979, in contrast, can be divided into two periods: the years 1971–1973, in which Egypt sought a rivalry de-escalation that was unsuccessful, and the years 1974–1979, in which Egypt's initiatives finally paid off in bringing about a de-escalation. The model again applies quite well. It shows that despite the presence of shocks in the first phase (see Table 4.2) none of the remaining variables were present on both sides of the rivalry in the years 1971–1973. However, in the subsequent period, all the critical variables (with the exception of Rabin's consolidated leadership) were present on both the Egyptian and Israeli sides. These cases remind us that shocks do not always have an immediate dampening effect on rivalry hostilities and in those cases where shocks do indeed bring about a new strategic orientation, such reorientations do not occur simultaneously on both sides of the rivalry. Lags in reaction can occur. The same can be said for the other key variables of the model. Hence, rivalry de-escalation would appear to be the consequence of good timing by a range of actors both inside and outside the rivalry. Policy changes are most likely to be achieved when the “stars”—in this case, the presence of the critical variables—are in alignment. When they are not, considerable diplomatic frustration is likely to be the norm.

Table 4.2. Shocks in the Egyptian-Israeli Rivalry, 1970–1979