CHAPTER 6

The Indo-Pakistani Rivalry, 1947–2010

The Indo-Pakistani rivalry has proven to be one of the most enduring conflicts of the post–World War II era. It has resulted in four wars (1947–1948, 1965, 1971, and 1999) and multiple crises, several of which almost culminated in war. Since 1998, this rivalry has also acquired an overt nuclear dimension. Unilateral, bilateral, and multilateral efforts to bring it to a close have proven to be mostly fruitless. The origins of this rivalry have been discussed at length elsewhere (Ganguly 1994; Paul 2005). Suffice it to say that the conflict can be traced to the process of British colonial disengagement from the subcontinent in 1947 and the competing visions of state construction in South Asia. The two successor states of the British Indian Empire in South Asia, India and Pakistan, were created on the basis of divergent conceptions of nationalism. Indian nationalism was fundamentally secular and civic and Pakistani nationalism was ethnic. The two divergent visions clashed over the control of the Muslim-majority state of Jammu and Kashmir (Brines 1968).

This chapter will show how despite external shocks, third-party pressures, and the presence of change-seeking entrepreneurs there has been only one important time span (1972 to 1979) when the rivalry saw significant de-escalation. However, even during this period the underlying sources of discord remained unabated. Intransigence and a lack of reinforcement from the adversary as well as other exogenous shocks brought this period of de-escalation to a close. To that end, this chapter will explore efforts at de-escalation in 1962–1963, 1966, 1972, 1980, 1989, 1999, 2004–2007, and 2009–2010.1

Focusing on the evolution of the rivalry, the several attempts at its de-escalation are framed within a series of several distinct historical phases. The phases are 1947–1966, 1967–1971, 1972–1989, 1990–1998, and 1998 to the present. This periodization is not idiosyncratic. Compelling historical and structural factors can be advanced to justify it. Beginning in 1947, the initial phase of the rivalry culminated in the Indo-Pakistani war over Kashmir in 1965 and the subsequent Soviet mediation of the conflict in 1966. The next phase lasted from 1967 to the third Indo-Pakistani war of 1971 and the bilateral peace agreement of 1972. The third phase, a period of relative quiet, lasted until 1989. It metamorphosed after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and lasted until the Soviet withdrawal in 1990. A new phase began in 1990 and lasted until the Indo-Pakistani nuclear tests of May 1998. It entered its most recent phase in 1999 with the Kargil war and continues until today. These periods have seen the rivalry wax and wane but have experienced only one viable move toward rapprochement. This move toward de-escalation came in the wake of Pakistan's overwhelming military defeat in 1971 and the Shimla Accord of 1972.

Phase One: The Origins and Evolution of the Rivalry

A brief discussion of the origins of the rivalry is necessary. The rivalry stems from competing visions of state construction in South Asia. The Indian nationalist movement was predominantly secular and had sought to create a civic, democratic polity. The Pakistani nationalist movement, in contrast, had sought to create a homeland for the Muslims of South Asia. The Muslim League, which had spearheaded the demand for Pakistan, had argued that despite the professed commitment to secularism, Muslims, as the largest minority community in the British Indian Empire, would be at a disadvantage in a predominantly Hindu India. In effect, they argued that the Indian National Congress, the dominant party of the Indian nationalist movement, had failed to make a credible commitment to protect the rights of Muslims in an independent India.2

These two competing conceptions of state construction clashed over the question of the division of the British Indian Empire following colonial disengagement. At the time of colonial withdrawal, two classes of states had existed in the empire. They were the states of British India directly ruled from Whitehall and the so-called princely states, which were nominally independent but had recognized the “paramountcy” of the British crown. With the departure of the British from the region, Lord Mountbatten, the last viceroy, decreed that the doctrine of paramountcy would lapse and that the princely rulers would have to choose between India and Pakistan. He also added that predominantly Muslim states, which were geographically contiguous, would join Pakistan.

The principal problem between India and Pakistan arose over the status of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. This state was predominantly Muslim, had a Hindu monarch, and shared borders with both India and Pakistan.3 India laid claim to Kashmir to demonstrate that a predominantly Muslim state could exist within the confines of a secular polity. Pakistan (Bhutto 1969), with equal force, argued that without Kashmir, its identity as the homeland for the Muslims of South Asia would remain incomplete. These pristine commitments have lost much of their force over the past fifty odd years. Pakistan could not endure on the basis of religion alone. The rise of Bengali linguistic nationalism contributed to Pakistan's collapse in 1971. If religion alone could not provide the basis of state construction, then the Pakistani irredentist claim to Kashmir was basically meaningless. Similarly, India, though formally a secular state, has failed to guarantee the rights of its Muslim and other religious minorities on multiple occasions (Ganguly 2003). Consequently, to claim that India must necessarily hold on to Kashmir to ensure its secular status is equally flawed.

At the time of independence and partition, these principles, however, had much greater significance to elites of both sides. Thus, contrary to popular belief, Pakistan did not initiate the war over Kashmir in 1947–1948 for strategic or material reasons. It did so primarily because its founding elite believed in the importance of Muslim confraternity in South Asia (Khan 1970). Kashmir, as a predominantly Muslim state with a border contiguous to Pakistan, had to be incorporated into Pakistan.

The conflict ended with India referring the case to the United Nations Security Council under the terms of a breach of international peace and security. On January 1, 1949, the United Nations declared a cease-fire and both sides accepted it. Subsequently, the dispute became a subject of vigorous (and highly partisan) multilateral diplomacy at the United Nations until about 1960. Neither side, however, showed much willingness to cede ground and the issue quickly became deadlocked.

During this period, three critical shocks, two exogenous, the other endogenous to the region, led to the intensification of the rivalry.4 The first came as early as 1954 with the Eisenhower administration's decision to make Pakistan a key ally in the strategy of containment.5 The interests of the two sides, of course, were far from convergent. Pakistan sought to bring the United States into the region to balance Indian power. The United States, however, convinced itself that Pakistan, as a predominantly Muslim nation, would serve as a bulwark against Communist expansionism.6 President Eisenhower's oft-cited letter in which he sought to allay Prime Minister Nehru's concerns about U.S. weaponry being used against India offered little solace to either Nehru or his cabinet (Gould and Ganguly 1992). Even though India's defense spending did not dramatically increase in response to the growth of Pakistani military power, the tenor of the relationship certainly worsened.7

The second shock came a mere four years later. As Pakistan's first constitutional order proved far too brittle the military seized power in 1958. The precise social and political forces that contributed to the seizure of power are not a matter of immediate concern. They have been discussed at length elsewhere (see McGrath 1996). The end of Pakistan's brief experiment with democracy deeply disturbed Nehru, still the principal architect of India's foreign policy and a committed democrat (Brown 2003). Nehru correctly feared that a military regime would prove to be even more intransigent in its dealings with India. Misgivings about Pakistan, which were already rife amid India's foreign policy elite, simply deepened.

The third shock that profoundly deepened the rivalry was the Chinese attack on India's northern borders in 1962.8 The impact of this exogenous shock to India's foreign and security policies cannot be overstated. Even though India's leaders continued to rely on the hoary language of Third World solidarity and nonalignment, the ideational elements of India's policies started to wither away. Indian decision makers increasingly came to the realization that moral suasion counted for little in the harsh world of global politics. Nehru's vision of an alternative global order based upon an abiding faith in multilateral institutions, the creation of new global norms, and self-imposed restraints on the use of force was all but abandoned.

The Shock of 1962 and Thereafter

In October 1962, the Indian Army suffered its most dramatic military defeat at the hands of the Chinese People's Liberation Army. Troops who were ill-equipped, inadequately armed, and unprepared for high-altitude combat faced a battle-hardened and carefully deployed Chinese army with disastrous consequences along India's Himalayan border.9 The attack came as a dramatic surprise to the Indian political-military establishment and resulted in a near complete rout of the Indian armed forces (Palit 1991). In the aftermath of this conflict, a serious debate ensued in India about the wisdom of low defense expenditures and the pursuit of a policy of nonalignment. Despite a vigorous debate, the country chose not to abandon its nonaligned policies but did seek limited military assistance from the United States.10 Also, it embarked on a significant program of defense modernization. India decided to acquire an air force of forty-five squadrons equipped with supersonic aircraft, it decided to raise the manpower ceiling of the Indian army to a million men, and it chose to raise ten new mountain divisions trained and equipped for high-altitude warfare. Finally, it set in motion a limited program of naval modernization.

India was briefly militarily dependent on the Western powers, most notably the United States and the United Kingdom, for military assistance. Owing to the Cold War exigencies of courting Pakistan, the United States and the United Kingdom exerted pressure on India to settle the Indo-Pakistani dispute on terms favorable to Pakistan. As a consequence of this pressure, the two sides did hold a series of negotiations in late 1962 and early 1963. These discussions almost culminated in a settlement of the Kashmir dispute on the basis of a territorial division. However, owing to the intransigence of the principal Pakistani negotiator, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the talks ended in a deadlock (Kumar 2005). The specific reasons underlying Bhutto's unwillingness to compromise remain unclear. However, it may have been rooted in his belief that India was in a fragile state in the wake of the border war with China in 1962 and that subsequent military pressure might induce India to make territorial concessions in Kashmir (Bhutto 1969).

In the absence of the external shock of the war with China in 1962 and India's acute dependence on the Western powers for military assistance, it is most unlikely that Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru would have consented to holding talks with Pakistan. Yet despite the talks that were held, de-escalation was undermined because of the intransigence of key individuals and the lack of reciprocity. The Indian political leadership then (and even today) would readily settle for a territorial division of the state that reflected the disposition of forces at the end of the conflict of 1947–1948.

The very insubstantial U.S. arms assistance coupled with India's ambitious military modernization plans caused alarm in Islamabad. Pakistani decision makers promptly suggested that these U.S.-supplied weapons, ostensibly directed against a Chinese threat, would be used against Pakistan. This argument was both disingenuous and self-serving. India was now a status quo power with respect to territory and faced a palpable threat from China. However, India's military modernization would indubitably undermine any Pakistani military efforts to wrest Kashmir back through the use of force.11 Not surprisingly, the Pakistani military dictatorship of Field Marshal Mohammed Ayub Khan devised an elaborate plan to try and seize Kashmir through the use of force. This plan, Operation Gibraltar, culminated in the second Indo-Pakistani war of 1965. The war, which was brief, ended mostly in a military stalemate with India making some small territorial gains in Kashmir. These gains, however, were ceded to Pakistan in the Tashkent Agreement of 1966, which restored the status quo ante (more details can be found in Ganguly 1990).

Negotiations at Tashkent

The bilateral negotiations at Tashkent transpired because of third-party intervention. Specifically, the United States chose not to broker a postwar settlement, thereby enabling the Soviets to step into the breach. Accordingly, Leonid Brezhnev invited Prime Minister Shastri of India (who had succeeded Nehru in 1964) and President Mohammed Ayub Khan of Pakistan to the then Soviet Central Asian city of Tashkent for a postwar negotiation. Thanks to Soviet cajolery the two sides managed to reach an agreement. Under the terms of the Tashkent Agreement of 1966 India chose to return the strategic Haji Pir Pass over the objections of the Indian army, restoring in effect, the status quo ante. Furthermore, both parties also agreed to eschew the use of force in settling the Kashmir dispute.

Once again the exogenous shock of the war and the eagerness of the Soviets to enter the subcontinent provided the basis for this attempt at de-escalation of the conflict. Though Soviet intervention provided the two parties with a venue to resolve their immediate differences it did not address the underlying causes of the dispute or either side's expectations. Consequently, the effects of this round of de-escalation were mostly cosmetic excepting the return of the Haji Pir Pass.

Phase Two: The Rivalry Worsens

Despite the military stalemate that resulted from the 1965 war, Pakistani political-military elites remained unreconciled to the status quo in Kashmir. With the imposition of a U.S. arms embargo on Pakistan following the war, however, they were no longer in a position to embark on yet another conflict with India.

The reduction in bilateral tensions by default proved to be quite short-lived because internal unrest within East Pakistan spilled over into India in 1971, culminating in the third Indo-Pakistani conflict.12 The third war did not start over the question of Kashmir. Instead it arose from the dynamics of Pakistan's internal political processes. The crisis stemmed from the structural imbalances that had long characterized the two wings of the Pakistani state. East Pakistan, for all practical purposes, had been treated as an internal colony of West Pakistan. The consequent grievances of the East Pakistanis ultimately broke through in the first free elections that Pakistan held in 1970. A regional, pro-autonomy party, the Awami League, won an overwhelming victory in East Pakistan. The Pakistani military establishment, as well as the Pakistan People's Party, which was based in West Pakistan, were utterly unprepared for this outcome. As protracted and convoluted negotiations over power sharing collapsed in March 1971, the Pakistani army resorted to a brutal and callous campaign of mass murder in East Pakistan, designed to cow the attentive public. Faced with this reign of repression, over the next several months some ten million individuals took refuge in India.

By May 1971, Indian authorities had decided that India was not in a position to absorb the refugees into its already large population. They also realized that barring some dramatic action on the part of the global community, Pakistan would not create conditions conducive for the return of the refugees (Jacob 1997). Accordingly, Indian decision makers swiftly forged a political-military strategy to alert the global community of the crisis. Simultaneously, it carefully laid plans for an invasion of East Pakistan in the event diplomatic initiatives did not produce the desired results. After some months of feverish diplomatic activity that yielded little or nothing concrete, Indian decision makers decided that they would invade East Pakistan with the goal of establishing a separate state. In preparation for this endeavor they signed a treaty of “peace, friendship and cooperation” with the Soviet Union. The treaty, among other matters, committed the two parties to come to each other's assistance in the event of an attack by a third party. The treaty effectively neutralized any possible military threat from the People's Republic of China.13 With the diplomatic initiatives exhausted, the treaty in place, and its military forces appropriately arrayed, India embarked upon a short, swift war that resulted in the rout of the Pakistani forces in East Pakistan within a span of two weeks. The concomitant breakup of Pakistan contributed to the creation of the state of Bangladesh.

In the aftermath of the conflict, India and Pakistan negotiated a bilateral agreement at the Indian hill station of Shimla in 1972 that normalized diplomatic relations, contributed to the return of ninety thousand Pakistani prisoners of war, and reiterated their mutual commitment to the non-use of force to resolve the Kashmir dispute. It also changed the nomenclature of the U.N.-sponsored cease-fire line to the Line of Control, reflecting a shift to bilateralism in Indo-Pakistani relations.

The inferences that the Pakistani military made from this dramatic military defeat are worthy of discussion. Instead of recognizing that their flawed policies had led to the military debacle they chose instead to blame the key civilian decision makers, most notably Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Bhutto's culpability in precipitating the crisis of 1971, of course, is indisputable (Zaheer 1994). That, however, could not exonerate the military for the long years of gross and abject neglect of East Pakistan, of the systematic discrimination against Bengalis in the armed forces and the civil service, and the reign of repression they had unleashed in East Pakistan in March 1971.

Nonetheless, India had emerged as the clear, undisputed winner of this war and also as the dominant power in the region. Pakistani decision makers, while still unprepared to accept the territorial status quo in the region, nevertheless were forced to come to terms with the dramatic asymmetry in mutual power relations. Under the leadership of Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Pakistani decision makers decided to embark on a covert nuclear weapons program. In their view (Ahmed 1999), the acquisition of a nuclear weapons option would compensate for Pakistan's fundamental conventional asymmetry.

This time an interaction between endogenous and exogenous shocks resulted in a significant de-escalation of the rivalry. The endogenous shock emerged from the uprising within East Pakistan, and the military rout at the hands of its principal adversary, India, constituted the exogenous shock. Pakistan suffered a major military defeat and, in effect, emerged as the weaker power in South Asia. Consequently, it was forced to reassess its foreign policy behavior. It could ill-afford to initiate conflicts with a neighbor that now possessed overwhelming conventional superiority and a much larger economy. Consequently, Indo-Pakistani relations assumed a semblance of normalcy between 1972 and 1979.

Phase Three: A Stable Peace in South Asia?

In the aftermath of the Shimla Accord of 1972, the manifest features of the rivalry largely abated, even though the rivalry's underlying sources remained unaddressed. When the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan took place in 1979, an important opportunity for Indo-Pakistani rapprochement opened up. The two sides could have, through adroit diplomacy, managed to present a common front against the Soviet intrusion into the region's affairs. Indeed, to this end, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi dispatched Narasimha Rao, his minister for external affairs and a veteran Congress politician, to reassure General Zia-ul-Haq that India would not seek to exploit Pakistan's emergent security dilemma. His effort, however, was both unheralded and fruitless, as General Zia sought to exploit the adverse situation to bolster the tenuous legitimacy of his military regime. Instead of seeking a regional solution to the crisis he actively courted the United States largely in an effort to obtain economic and military largess.14 More to the point, he, as well as significant segments of the Pakistani political-military establishment, remained utterly unreconciled to the territorial status quo in South Asia. Additionally, the military deeply resented India's role in the creation of Bangladesh (Arif 1995). Many in the military establishment sought opportunities to exploit cleavages within India for its role in the breakup of Pakistan in 1971.

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979 significantly altered the security situation in South Asia (Bhargava 1983). Pakistan had been at odds with the Carter administration because of significant differences over human rights and nonproliferation issues. However, with the Soviet presence in Afghanistan the administration in its final year did an abrupt about-face. It anointed Pakistan as a “front line” state and offered $400 million in economic and military assistance.

Sensing that the Pakistani military dictator, General Zia-ul-Haq, would seek to exploit the Soviet presence in Afghanistan, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi sent her foreign minister, Sardar Swaran Singh, to Islamabad to proffer a regional solution to the crisis. In Islamabad Singh sought to reassure India's principal adversary that it would not exploit Pakistan's emergent security concerns. These efforts, however, proved to be of little consequence. General Zia-ul-Haq showed scant interest in Prime Minister Gandhi's proposals and also dismissed President Carter's offer of assistance as “peanuts” (Duncan 1989).

Shortly thereafter, in 1981, with the advent of the Reagan administration, Pakistan became the recipient of considerable U.S. largesse. Not surprisingly, India turned to the Soviet Union for weaponry to counter Pakistan's military acquisitions. Any hope of de-escalation in tensions simply evaporated for the next decade. The Soviet invasion, a significant exogenous shock to the region, had held open the possibility of a de-escalation of tensions, especially in light of Indira Gandhi's efforts at reassurance. Yet the Pakistani military establishment under General Zia-ul-Haq displayed no interest in reciprocity.15

Even with substantial U.S. military assistance, Pakistan was unable to embark on a full-scale conventional assault on India because of significant and growing military asymmetries.16 Nevertheless, Pakistan chose instead to exploit existing tensions within India. Accordingly, in the 1980s, for example, the military regime of General Zia-ul-Haq became deeply embroiled in training, supporting, and providing sanctuaries for Sikh insurgents in the Punjab. The roots of the insurgency were indigenous, but Pakistani assistance prolonged its duration and increased its intensity (Wallace 1995). Pakistani support for the Sikh insurgents coupled with India's growing frustration with its inability to suppress the insurgency contributed to a significant crisis in Indo-Pakistani relations in 1987. The Indian military exercise, Brasstacks, which was designed partly to signal India's ability to strike Pakistan despite the ongoing insurgency in the Punjab, helped trigger this crisis (Bajpai et al. 1995). Some tentative evidence (Ganguly and Hagerty 2005) suggests that India was deterred from escalating the conflict either horizontally or vertically for possible fears of a Pakistani resort to nuclear weapons.

Phase Four: Kashmir Redux

Pakistani decision makers, whether civilian or military, had refused to accept the political arrangement in Kashmir despite a professed commitment to the Shimla Accord of 1972.17 The existing military balance, however, had simply rendered it impossible for Pakistan to seek to wrest Kashmir back from India through the use of force. It is entirely possible that the issue of Kashmir might have abated somewhat if an insurgency had not erupted in the state in December 1989. But that shock was preceded by another one: the death of General Zia-ul-Haq.

General Zia perished in a plane crash in July 1988. For various reasons, including U.S. diplomatic pressure, the Pakistani military chose not to cling to political power. As a consequence, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's daughter, Benazir Bhutto, assumed political office after a landslide electoral victory.

In India, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi had succeeded his mother following her assassination in 1984. With the emergence of a democratically elected leader in Pakistan, he and others believed that an opportunity to reduce tensions had opened (Dixit 2002). Accordingly, he initiated talks with Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto of Pakistan. These talks initially generated three substantive agreements on nuclear confidence-building measures, international civil aviation, and a series of further meetings on matters related to border management, trade, and tourism (Dixit 2002: 268). However, they quickly fell victim to the exigencies of India's domestic politics.

In December 1989, an ethno-religious insurgency erupted in the Indian-controlled portion of the disputed state of Jammu and Kashmir. The origins of this uprising were indigenous and stemmed from the exigencies of Indian domestic politics (Ganguly 1997), in particular the growth of political mobilization in the state against a backdrop of steady political deinstitutionalization. The conjunction of these two forces proved to be a lethal amalgam. As a new, politically conscious generation of Kashmiris saw that institutional channels of dissent were blocked they resorted to violence to express growing political discontent. Once the insurgency had erupted, Pakistani decision makers, most notably in the military establishment, sought to mold, shape, and direct the course of the rebellion.

What was originally a spontaneous rebellion soon became an externally orchestrated extortion racket (Davis 1995). The Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan and the subsequent Soviet collapse also aided Pakistan in its ability to support the insurgents.18 Thousands of mujahideen whom the Pakistani military establishment had organized, trained, and supported, were now available for the conduct of yet another jihad.19

With this abrupt rise in anti-Indian sentiment across much of the Kashmir Valley, Benazir Bhutto came under considerable pressure from the Pakistani military as well as other hawkish forces within the polity to adopt a hostile posture toward India. Within weeks she made a series of intransigent public remarks that swiftly brought various ongoing discussions to a close. The possibility of de-escalation that had arisen was, yet again, lost.

Endogenous shocks were responsible for opening as well as closing this particular prospect of de-escalation. The first shock stemmed from the death of General Zia-ul-Haq and the concomitant emergence of a democratically elected regime in Pakistan. It was also helped by Rajiv Gandhi's assumption to the office of the prime minister upon the assassination of his mother. Neither Benazir Bhutto or Rajiv Gandhi had been a witness to the partition of the subcontinent and both were therefore more open to the possibilities of Indo-Pakistani accord.

They may not have been ardent change-seeking entrepreneurs, but they were nevertheless open to the possibilities of discussion and negotiation. However, Bhutto was especially vulnerable to structural and social forces with the Pakistani polity. Religious zealots, whom President Zia-ul-Haq had cultivated, and the military establishment were both arrayed against her. Consequently, once the sudden rebellion broke out in Kashmir, another endogenous shock, her room for political maneuvering was constrained and she felt compelled to publicly outbid the other strident voices from within Pakistan. Under these circumstances the de-escalation process, which was still in an incipient stage, came to a quick close.

Phase Five: From 1998 Onward

Another serious effort at the de-escalation of tensions in the subcontinent did not ensue for almost a decade. Ironically, it was the Indian and Pakistani nuclear tests of May 1998 that triggered the de-escalation process. After years of nuclear ambiguity, both India and Pakistan conducted nuclear tests in May 1998. The origins of their respective nuclear programs and their motivations have been discussed at length elsewhere (Ganguly 1999; Ahmad 1999). In the aftermath of the tests both states faced a spate of multilateral sanctions. More to the point, a number of important world leaders expressed grave concerns about the dangers of renewed conflict in the region culminating in nuclear war (Talbott 2006).

Probably with a view toward dispelling some of these concerns Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee of India initiated a bus service linking the cities of Amritsar (in India) and Lahore (in Pakistan) in February 1999. He also chose to visit Pakistan as he inaugurated the bus service. The visit was significant for its symbolic and substantive elements. The symbolism of the visit was important because Vajpayee, the leader of a right-wing, Hindu chauvinist political party, had chosen to visit Pakistan. More to the point, he specifically chose to go to the Minar-e-Pakistan, the site where the Muslim League had passed the original resolution for the creation of Pakistan in 1940 (Chari, Cheema, and Cohen 2007: 121). At that venue, Vajpayee publicly affirmed India's commitment to the territorial integrity of Pakistan.

Beyond these symbolic gestures of note the Lahore Declaration also sought to promote confidence-building measures designed to prevent the accidental or unauthorized use of nuclear weapons and called for a resumption of a composite dialogue to address a range of outstanding differences. Despite these symbolic gestures and substantive commitments the Lahore peace process quickly unraveled.

This attempt at de-escalation came to a close because the Pakistani military chose to launch a military operation across the Line of Control (the de facto international border) in the Kargil region of the state of Jammu and Kashmir.20 When the Indian military discovered these incursions in early May 1999 it responded with considerable vigor while keeping the ambit of the conflict carefully limited to the Kargil region. Unlike in past conflicts where India had resorted to horizontal escalation through the opening of a second front, on this occasion it chose not to do so. In all likelihood, India's unwillingness to expand the scope of the conflict stemmed from its knowledge that such a widening could contribute to an escalatory spiral resulting in a Pakistani threat to resort to the use of nuclear weapons (Ganguly and Kapur 2010). Through the steady, unwavering but calibrated application of force India prevailed in the war. Around mid-July India had succeeded in ousting all the Pakistani intruders.

Significant external pressures that the nuclear tests had generated were the principal reasons for the genesis of this attempt at de-escalation. In effect, the overt nuclearization of the region had amounted to a radical change in its security milieu. Ironically, then, the tests need to be seen as the shock that prompted the pressures for de-escalation. Unfortunately, the fragmented power structure within Pakistan where the military had remained primus inter pares despite the presence of a civilian regime contributed to the lack of reciprocity and the failure of de-escalation. Worse still, it had actually contributed to an escalation of tensions through the Kargil misadventure.

The nuclearization of the region did not inhibit the Pakistani political-military establishment from making a renewed attempt to revive the Kashmir issue. On the contrary, it was emboldened in its resolve. It had correctly concluded that the fear of escalation to the nuclear level would inhibit the Indian security forces from expanding the scope of the conflict either vertically or horizontally (Ashraf 2004). In April 1999 Pakistani forces disguised as local tribesmen made a series of bold forays across the Line of Control in the Kargil district of Kashmir at altitudes of about sixteen thousand feet. Though they achieved tactical surprise, they failed to consolidate their gains. The areas where they made these incursions were extremely inhospitable, mostly snowbound for the bulk of the year, and were not easy to resupply. Once the Indian military discovered these incursions it launched a vigorous and unyielding campaign to dislodge the intruders. Within three months of the initial incursions the Pakistani forces had been pushed back to their original positions.

What was the principal purpose of these incursions? As argued earlier, by the late 1990s, India had succeeded in restoring a modicum of order to Kashmir. More to the point, the global community was increasingly losing interest in the Kashmir question. In large part, Pakistan chose to make these forays across the Line of Control to try and revive international interest in the Kashmir question. Mediation by the United States provided Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif of Pakistan a face-saving pathway out of this crisis (Talbott 2004). Despite the Pakistani withdrawal from the occupied positions, support for the Kashmiri insurgents did not come to a close. If anything, following a military coup against Prime Minister Sharif in October 1999, support for the insurgents increased.

Even after the tragic events of September 11, 2001, and U.S. pressure on Pakistan to end its ties to the Taliban regime in Afghanistan in particular and terrorist organizations in general, Pakistan refused to terminate its support for a range of insurgent groups operating in Kashmir. On December 13, members of two of these groups, the Lashkar-e-Taiba and the Jaish-e-Mohammed, launched a daring attack on the Indian parliament in New Delhi. Even though they managed to penetrate the security cordon of the parliamentary enclosure they were subsequently stopped and killed in the ensuing gun battle. In the aftermath of this episode, India embarked upon a large-scale military mobilization effort designed to coerce Pakistan to put an end to support for the insurgents. This exercise in coercive diplomacy, Operation Parakram, which lasted several months, nearly brought the two sides to the brink of war. Substantial U.S. engagement on both sides of the border played an important role in eventually defusing the crisis in the late summer of 2002 (Ganguly and Kraig 2005).

Continuing Deadlock: The Composite Dialogue

In 2003, Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee again offered a resumption of talks with Pakistan. The motivations underlying his offer to hold talks with Pakistan remain unclear. It is possible that given the success of India's counterinsurgency strategy in Kashmir, which had managed to restore a semblance of political order and stability, he saw a renewal of talks with Pakistan as a possible pathway toward addressing the underlying sources of conflict. In any case, Pakistan reciprocated later in the year with the banning of two terrorist organizations and the imposition of a cease-fire along the Line of Control (Chari, Cheema, and Cohen 2007: 208).

By 2004, a full-scale, “composite dialogue” was under way with a range of issues extending from nuclear confidence-building measures to the demilitarization of the Siachen Glacier under discussion. According to one of the few accounts of the dialogue, considerable progress was made between 2004 and 2007 in addressing these issues. Unfortunately, domestic opposition to General Musharraf's regime, unrelated to his pursuit of this peace process with India, led to its petering out.21

With the civilian interregnum in Pakistan and a change in the key political actors the dialogue lost its momentum. Worse still, in November 2008, a group of ten terrorists affiliated with the Lashkar-e-Taiba attacked a series of targets in a well-coordinated fashion across Bombay (Mumbai), India's principal commercial and entertainment hub. For a host of complex reasons it took Indian security forces over three days to completely quell the terrorist attack (Rabasa et al. 2009). Despite the viciousness of the attack and India's ability to trace the origins of the terrorists to Pakistani soil based upon electronic intercepts, the Congress-led regime of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh avoided any resort to military action. In all likelihood India decided not strike Pakistan for two reasons. First, in the time that it took the security forces to bring the terrorists to heel any element of surprise was lost. It was entirely reasonable to surmise that Pakistani forces were in a suitable state of alert to repulse or respond to an Indian military strike. Second, the fear of nuclear escalation that had long dogged Indian military planning no doubt played a role in curbing an incentive to carry out military action. However, the regime in New Delhi felt compelled to end the ongoing dialogue.

What had initiated the “composite dialogue” in the first place? Vajpayee and Musharraf must be seen as change-seeking entrepreneurs. Though Vajpayee made the initial move he enjoyed a degree of reciprocity from Musharraf. Musharraf, it appears had learned that no quick resolution to longstanding and deep-seated differences was possible through political grandstanding. He had resorted to this tactic in the summer of 2001 during the Agra summit only to have hawkish leaders within the Indian cabinet quickly undermine his efforts. Indeed, without Musharraf's willingness to move forward with a substantive and meaningful dialogue Vajpayee's call for a dialogue would have been in vain. In this case, the talks, which appear to have made much progress, unraveled thanks to a domestic/endogenous shock, namely the political agitation within Pakistan that forced Musharraf from office.

In the aftermath of this crisis, after considerable prodding by the United States, some fitful efforts at rapprochement have taken place. For example, in April 2005 the two sides initiated a bus service linking their respective portions of the disputed state of Kashmir (Johnson 2005). The prospects of a breakthrough, however, remain unlikely. Far too many obstacles still lie in the path of any possible rapprochement. The Pakistani military, which received an important reprieve after September 11, 2001, and is now firmly ensconced in ruling the country, does not stand to benefit from a rapprochement with India. Such a settlement would call into question the very substantial resources at its command. At the same time, no regime in India will make significant territorial concessions for reasons that have been already discussed. More to the point, given that India is now on a sustained path of economic growth it can afford to devote substantial resources to its military and simply contain the Kashmir problem. The material and psychic costs of holding on to Kashmir are well within the purview of the Indian state. Accordingly, while it may be willing to pursue a range of confidence-building measures with Pakistan there is no willingness to pursue territorial compromise.22

A Dialogue of the Deaf: 2010

In April 2010 on the sidelines of the annual meeting of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, India and Pakistan chose to resume the dialogue that had been suspended in the aftermath of the Bombay terrorist attacks (Sharma 2010). It is widely believed that India chose to resume these discussions. Accordingly, the two foreign secretaries, Nirupama Rao of India and Salman Bashir of Pakistan, met in New Delhi in February 2010. These talks quickly deadlocked as the two sides remained wide apart on critical issues dealing with Kashmir and terrorism. However, they agreed to continue the dialogue (Husain 2010; see also Magnier 2010).

Accordingly, in July 2010, the Indian minister for external affairs, S. M. Krishna, traveled to Islamabad to resume discussions. This meeting, however, proved to be an utter contretemps. Shortly before Krishna's departure for Islamabad, in response to a direct question from a reporter, the Indian home secretary, G. K. Pillai, publicly stated that during his interrogation in Chicago, David Coleman Headley, a Pakistani-American charged in connection with the Bombay (Mumbai) terrorist attacks, had revealed that Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate, had helped coordinate the attack.23

Not surprisingly, the talks ended in a complete deadlock with mutual recriminations (Ganguly 2010). The popular explanation for the breakdown of the talks suggests that Pillai's untimely revelations about Headley undermined the talks (Hindustan Times 2010). There may be some truth to this allegation. However, it is also possible to argue that Shah Mehmood Qureshi, Pakistan's foreign minister, did not command the confidence of the all-powerful Pakistani military establishment. At a time when the security establishment under General Kayani found that it could influence Afghanistan's internal politics in light of the prospective U.S. drawdown of forces starting in July 2011, it saw little reason to improve relations with India (Tisdell 2010).

A change-seeking entrepreneur, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh had initiated this dialogue. Unfortunately, his interlocutor, President Asif Ali Zardari of Pakistan, was not an independent actor. The peculiar structure of civil-military relations within Pakistan had hobbled his policy choices. Consequently, his room for maneuver and that of his foreign minister, Shah Mehmood Qureshi, was severely constrained. The entrenched hostility of the Pakistani military establishment toward India makes reciprocity exceedingly difficult.

Conflict Escalation and De-Escalation in the Indo-Pakistani Rivalry

Why have multilateral, third party, and bilateral initiatives failed to resolve this conflict? Why have both endogenous and exogenous shocks failed to dramatically alter the course of this rivalry in a positive fashion? The answer to these questions will necessarily be partial. One possible way to address them may be to tease out some general propositions about this rivalry from the complex historical record.

First, the rivalry involves two states with markedly different regional agendas. India, for the most part, has been and remains a status quo power. Even in the aftermath of the war in 1971, India did not engage in any attempt at territorial aggrandizement. It did contribute to the breakup of Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh. However, it did not in any way seek to augment its territorial status. Pakistan, in contrast, has consistently been a revisionist power. Despite grave asymmetries of power, it has repeatedly sought to change the territorial status quo in South Asia since 1947. Even after the overt nuclearization of the region in 1998, it attempted to alter the status quo in Kashmir in 1999. Amid the ongoing discussions of 2005, Pakistani interlocutors continue to keep Kashmir at the forefront in all of their discussions with India. Pakistan's obsession about Kashmir is certainly one of the factors that has helped keep the rivalry alive. As Steve Cohen, a noted U.S. observer of Pakistan, has written (Cohen 2004): “Over the years, Kashmir has become part of the Pakistani identity—at least, of those Pakistanis who focus on strategic and security issues, notably the army—and it raises deep passions and emotions, especially among the large Kashmiri population in important Pakistani cities.”

If the defense of secularism is no longer as critical for India, then what explains India's unwillingness to accept a territorial compromise? The answer is complex. In considerable part it is because Indian elites fear an internal domino effect. If Kashmir or a part thereof is allowed to secede from the Indian union, then a powerful demonstration effect could be set into motion. Other disaffected groups in key states may see the Kashmiri secession as a precedent for their own.24

A second explanation for this enduring strategic rivalry lies in state structure. The domestic features of the Pakistani state, where the military establishment is primus inter pares, makes the resolution of this conflict exceedingly difficult. Embellishing the putative threat from India justifies substantial military expenditures in Pakistan and enables the military to retain its corporate privileges. To this end, it routinely fans the flames of hypernationalist propaganda and seeks to maintain an image of India's seemingly implacable hostility toward the very existence of the Pakistani state. Civilian regimes have not performed markedly better on this score. Since they have existed at the sufferance of the military their ability to shift the terms of popular and even elite discourse within Pakistan has been limited (Jones 2002).

More to the point, not a single civilian regime in Pakistan has been allowed to sustain a full term in office. Consequently, democratic consolidation has failed to take place within Pakistan. Fledgling democratic regimes, often seeking quick populist pathways to bolstering their legitimacy, have simply sought to outbid the military in their dealings with India. As a consequence, neither weak civilian regimes nor well-entrenched military regimes have evinced much interest in seeking rapprochement with India.

The depth and intensity of this rivalry precludes most possibilities of its swift resolution. In all likelihood the rivalry will continue for the foreseeable future. In the longer run, two key factors will determine the dimensions of the rivalry. First, the rivalry will lose its significance as India continues to grow at much higher rates, becomes more closely integrated into the global economy, and wields a much more powerful and sophisticated military. Second, it will also abate as India manages to limit the scope of internal conflicts that are susceptible to external manipulation. Both factors should work in tandem. The growing military and economic gap between the two states should limit Pakistan's capacity and propensity to provoke and needle India. Simultaneously, India's ability to forestall, manage, and contain internal conflicts will hobble the opportunities for Pakistani involvement.

Of course, the gap between the two states is not exactly a new factor. Capability asymmetry has hardly constrained Pakistan from provoking India to date. Nor is Indian success in managing its internal conflicts something to be taken for granted. With the passage of time, while the two states may not forge cordial relations, the rivalry could cease to matter to the extent that India's substantially greater military prowess, its economic stature, and its political stability prevails. Then again, there is no guarantee how long this passage of time will take.

But where do external shocks, third-party pressures, and change-seeking entrepreneurs fit into this picture? Despite the presence of these factors, there has been only one important time span (1972 to 1979) when the rivalry saw significant de-escalation. However, even during this period the underlying sources of discord remained unabated. Intransigence and a lack of reinforcement from the adversary as well as other exogenous shocks brought this period of de-escalation to a close.

Table 6.1. Shocks in the Indo-Pakistani Rivalry, 1947–2010

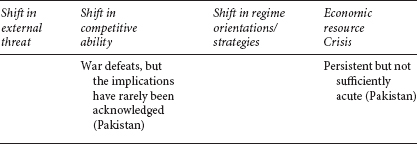

What then does the Indo-Pakistani rivalry tell us about our expectancy theory? Table 6.1 suggests, not unlike the Israeli-Syrian case, that shocks—which have certainly been present in the relationship—do not appear to be critical to bringing about rivalry de-escalation/termination. Or, perhaps one should infer that this rivalry has not experienced the appropriate type of shock so far. Yet the Indo-Pakistani case is much like the Israeli-Syrian case in the sense that the weaker member of the pair has been defeated substantially and repeatedly. One might think defeat in war would be as great a shock as is imaginable, subject, that is, to one important caveat. Defeat in war once meant (as recently as 1945) that the losing side lost much if not all of its territory and independence. Both Syria and Pakistan have lost territory, but they have not lost their independence. War defeats can be less shocking than they might otherwise be if the full impact of losing a war is constrained by international norms and third parties.

Just how important this might be in the Indo-Pakistani case is difficult to assess. Equally important, though, we find no links between shocks and expectancy revision. The shocks are there, but their impact is usually to make the rivalry relationship more intense. No expectancy revision has been demonstrated to date. Both sides continue to regard the other as threatening. The most appropriate sort of shock is one that leads directly to expectancy revision and, for various reasons as recounted above (for instance, misperceptions and the nature of Pakistan's political elite), that has yet to come about.

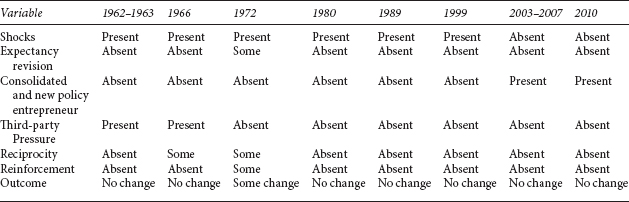

Some of the other factors are not entirely absent in Table 6.2. Third-party pressures have been evident from time to time. Some acts of reciprocity, such as reducing barriers to travel or exchanging prisoners, have been seen as well. But these factors do not carry sufficient weight, in and of themselves, to bring about a substantial de-escalation. The relative absence of new change entrepreneurs in this rivalry makes it rather difficult to assess its importance. That evaluation will require more cases.

Table 6.2. Modeling Outcomes for the Indo-Pakistani Rivalry

Significant de-escalation of the Indo-Pakistani rivalry has only taken place in the face of shocks that have left the Pakistani military establishment weakened. Consequently, the rivalry lessened significantly in the aftermath of the war in 1971, which had left the military in morally discredited and materially crippled. The military's intransigence toward India, which helps sustain its extraordinary privileges, cannot be easily overcome. One of two possibilities will end this rivalry: 1) the Pakistani state and especially the military apparatus will inexorably come to the realization that they cannot compete with India and that it thereby makes sense to abandon a policy of unremitting hostility (Ganguly 2006); or 2) a powerful third party, which has the incentive and the capabilities to alter the internal structure of the Pakistani state, will diminish the overweening role of the security establishment. In the absence of these two conditions it is unlikely that there will be much abatement of the Indo-Pakistani rivalry in the foreseeable future.