Kinship

Twenty-five years of Aboriginal kinship studies

At the conference on Aboriginal studies twenty-five years ago John Barnes and Mervyn Meggitt presented papers on social organisation, the equivalent topic to my own. John Barnes was not surprised that for many Aboriginal societies the only data available consisted of marriage rules, kinship terms and the names of subsections, sections and moieties, given the special difficulties and limitations facing the ethnographer working in Australia. He commented (in Sheils 1963, 205):

even this meagre amount of information is sufficient to define a formal structure of considerable complexity. These formal structures have considerable aesthetic appeal and comprehending their logical properties tests the intellectual agility of those who analyse them. Many anthropologists have, alas, been mesmerised by these systems; their study has become a recognised speciality and attention has been diverted from discovering how these systems actually work in Australia. The latter task is certainly the harder one but It is I think the more Important.

In discussion, Barnes touched on the neglect of the study of territorial organisation, closely tied to economic activity, and the relation between the conceptualisation of territory and land tenure and use (in Sheils 1963, 227).

In a similar vein Meggitt commented that accounts of social organisation should go beyond the merely structural (in Sheils 1963, 212). He thought there was little left to do in the way of recording the salient formal features of kinship systems, or of the general geographical distribution of the main types. Detailed analyses of observed behaviour were available only for a few ‘tribes’, and attempts at quantification were rare (in Sheils 1963, 213). Knowledge of the structure of descent groups was even more limited outside Arnhem Land and central Australia. Least was known about local organisation, and it was unlikely that more would ever be known because local groupings as well as economic activities were the first elements of social life to break down under European impact. Meggitt predicted pessimistically that for these matters as well as the organisation of other forms of grouping we have little information and, for practical reasons, no prospect of acquiring much more. Anthropologists would do better to focus less on traditional society, and more on ‘the plural society of Aborigines, Europeans, Asians and people of mixed ethnic origins’ (in Sheils 1963, 216).

In his comments on the papers RM Berndt was more optimistic about achievements and prospects, but urged comparative studies similar to African Systems of Kinship and Marriage, in order to achieve understanding of the general principles underlying Australian systems of kinship, marriage and social groupings (in Sheils 1963, 224).

How far have these hopes and fears been borne out in the results of the twenty-five years of study of Aboriginal kinship, marriage and social organisation which have succeeded the 1961 conference? This topic of kinship is construed fairly broadly to include such matters as local organisation and section systems as well as descent, marriage and alliance. As a preface to the review I recount the legacy of Radcliffe-Brown, the dominant figure In Australian Aboriginal studies of the first half of this century, whose works have provided the terms of reference for the majority of studies in kinship and social organisation; and that of Lévi-Strauss. At the beginning of our period many students followed Radcliffe-Brown’s lead closely, but his assumptions and generalisations have been increasingly questioned and revised. Lévi-Strauss drew on Radcliffe-Brown’s synthesis in the construction of his theory of kinship (Lévi-Strauss 1949, 1969a) which has also shaped the path of subsequent kinship studies in Australia.

THE LEGACY OF RADCLIFFE-BROWN AND LÉVI-STRAUSS

Radcliffe-Brown developed in his 1930-31 papers an elegant and formally integrated view of kinship, social categories and local organisation. The basic elements of social structure are the family, the horde—‘a small group owning and occupying a definite territory or hunting ground’—and groupings for social purposes based on sex and age (1930-31, 34). The horde consists of male members, unmarried sisters and daughters of male members, and the wives of male members (1930-31, 35-36), and is the war making unit. Hordes are grouped into tribes, which have a certain homogeneity of language and custom, but lack political unity (1930-31, 36-37). Subsections, sections and moieties are part of the kinship system (1930-31, 42).

By ‘kinship’ Radcliffe-Brown means genealogical relationships; those ‘set up by the fact that two Individuals belong to the same family’, although paternity in Aboriginal society is ‘a purely social thing’ (1930-31, 42). Aboriginal society gives the widest possible recognition to genealogical relationships (1930-31, 43). Systems of kin classification are governed by three principles: the equivalence of brothers; the bringing of relatives by marriage within the classes of consanguineal relatives; and, although every term has a primary meaning, the non-limitation of range (1930-31, 44-45). There is a certain pattern of behaviour for each kind of relative, and the kinship system regulates marriage (1930-31, 44-45).

Radcliffe-Brown believed Aboriginal kinship systems to be similar in many respects, but to have many variations in others. The variations can be classified with reference to the form of marriage and the number of lines of descent in the kinship terminology

(1930-31, 47-53). In the Kariera system only two types of male kin are recognised in the grandparental generation so that the system ‘brings all collateral relatives into two lines of descent’. The Kariera system is correlated with, based on and implies the existence of cross-cousin marriage (1930-31, 46, 51). In the Aranda system four lines of descent are recognised, and a man marries his MMBDD, or a relative classified in the same way. The Kumbalngeri system is like the Kariera system in having two lines of descent, but a man may only marry a classificatory MBD or FZD. In the Wikmunkan system a man marries his MyDB, but not his MeBD. In the Karadjeri type, which includes the Murngin, a man marries his MBD but may not marry his FZD. The Yaralde type is similar to the Aranda type, but prohibits marriage with close relatives, on the basis of clan relationship. The Ungarinyin type has four lines of descent, but permits MMBSD marriage. The Nyul-Nyul is an aberrant type, and in a considerable part of the northwest coast of Australia a man may marry his ZSD.

Sections and subsections are part of the systematic classification of relatives in Radcliffe-Brown’s view, and the marriage rules between sections and so on result from the more fundamental marriage rules between kin. Patrilineal and matrilineal lines of descent constitute the moieties (1930-31, 53-55). Two tribes with the same section system may have very different kinship systems and marriage rules (1930-31, 58).

Despite certain formal inconsistencies and incompleteness, Radcliffe-Brown’s scheme has a great formal elegance, integrated as it is with a patrilineal, patrilocal model of local organisation. The very elegance of the paradigm, however, gave rise to anomalies when empirical data did not fit models within the scheme, the most notorious of which are documented in the Murngin literature (Barnes 1967).

Radcliffe-Brown’s social structural synthesis has informed in one way or another the studies of most workers in the field of Aboriginal kinship ever since. The second major paradigm to make its mark from the beginning of the period is alliance theory.

What has become known as the alliance approach to Aboriginal kinship studies, originated in the work of Lévi-Strauss (1949, 1969a), and the independent work of the Dutch School. Lévi-Strauss’s theory of kinship and marriage is difficult to summarise briefly, but the following points appear to be central (de Josselin de Jong 1962, Scheffler 1973a, Barnes 1971). Lévi-Strauss conceives of social structure as a model, and is concerned with universal constants of systems of categories and rules. Kinship systems are all built upon an ‘atom of kinship’ consisting of a man, his wife, his sister, her brother, and the children of the married couple. Marriage is a form of exchange between such units. The exchange of women is one of the three principal levels of communication—of women, goods and services, and messages—for it is men who control the destinies of women. Marriage exchange arises from the prohibition of incest, which is the fundamental step in the transition from nature to culture, and which establishes mutual dependency between families.

In the case of complex structures marriage choice is left to chance, whereas an elementary structure of kinship is one with positive marriage rules. Crow-Omaha systems are an intermediate type. Within the category of elementary structures, restricted exchange refers to symmetrical relations of exchange between an even number of groups; generalised exchange is asymmetrical, involves more groups, and is compatible with any number of groups. These forms correspond to varieties of cross-cousin marriage, and in general to disharmonic and harmonic regimes.

Under an ‘harmonic regime’ the rules of descent (Lévi-Strauss’s filiation) and of residence are either patrilineal and patrilocal or matrilineal and matrilocal. In a ‘disharmonic regime’ descent is patrilineal and residence matrilocal, or descent is matrilineal and residence patrilocal. The result of a disharmonic regime is a system of groups cross-cut by descent groups of the opposite type. Generalised exchange is usually harmonic, whereas restricted exchange is usually disharmonic. Generation based moieties arise from a disharmonic regime.

Lévi-Strauss’s theory was revised by Needham (1962a) and Maybury-Lewis (1965). Needham introduced the distinction between prescriptive and preferential rules, and argued that rules applied to categories are not reducible to genealogical relatives. It is to the analysis of kin classification that we now turn.

THE ANALYSIS OF ABORIGINAL SYSTEMS OF KIN CLASSIFICATION

Radcliffe-Brown’s typology of Aboriginal systems of kin classification has remained the standard reference point, although AP Elkin (1964) revised it to some extent without greatly extending it.1 Scheffler’s synthesis (1978) is both a tribute to, and a critique of, Radcliffe-Brown. It continues Radcliffe-Brown’s project ‘to reveal the structures and relations among the structures of Australian systems of kin classification’, and defends his view that the basis of Aboriginal kinship is genealogical, against those who argue that so called kin categories are social categories. However, while Radcliffe-Brown’s conceptual framework was social-structural, that of Scheffler is structural-semantic.

Radcliffe-Brown (1930-31) insisted on the genealogical basis of Aboriginal kin classification, although he regarded paternity as social. But are the Aboriginal relational categories commonly labelled ‘kin’ categories merely ‘social’ categories as Needham (1971) argues, or do they indeed have a genealogical basis? These questions have been recently reviewed by Scheffler (1978) who educes an impressive body of evidence that knowledge of the physiological role of men in reproduction is widespread among Aborigines, providing, with the matrifilial relation, the genealogical basis for kin classification (cf Ashley-Montagu 1974, Barnes 1973, Merlan 1986). Recent ethnographic accounts of conception beliefs (eg Tonkinson 1978a, Hamilton 1981) show both that beliefs are context dependent and that people posit a variety of causes of pregnancy. Furthermore, Scheffler argues that kin categories cannot be derived from so called ‘marriage classes’, because the latter are logically dependent on the former.

Scheffler (1978, x) criticises Radcliffe-Brown for failing to demonstrate that all Aboriginal systems of kinship and marriage are varieties of one general type, because of misconceptions about structural principles, and the confounding of structural-semantic with sociological accounts, Scheffier’s own account is based on formal semantic analysis developed by Lounsbury (1964), and Scheffler and Lounsbury (1971), among others. It entails the componential analysis of core ‘meanings’ of kin terms (exemplified also in Epling’s 1961 analysis of Njamal kin terminology), and the formulation of equivalence rules to account for other senses of the polysemous categories. The features and dimensions, or ‘principles of conceptual opposition’, posited by Scheffler are these: kinsman versus non-kinsman; lineal versus collateral; degree of generational removal; seniority; sex of Alter; relative sex; and sex of Ego. Primary categories are defined in terms of these components, and equivalence rules account for their extension to other genealogical referents. Scheffler augments this mode of analysis with the concept of ‘superclass’ to account for certain features of the Australian data. A superclass is a ‘generic, higher order, or more inclusive class, which consists of several subclasses’. For example, if the term for FZ is extended to all women whom Ego’s father classifies as ‘sister’, and some of those kin who are Ego’s potential mothers-in-law are picked out by an additional deslgnatum, then the latter as well as the residual class both comprise the superclass ‘FATHER’S SISTER’.

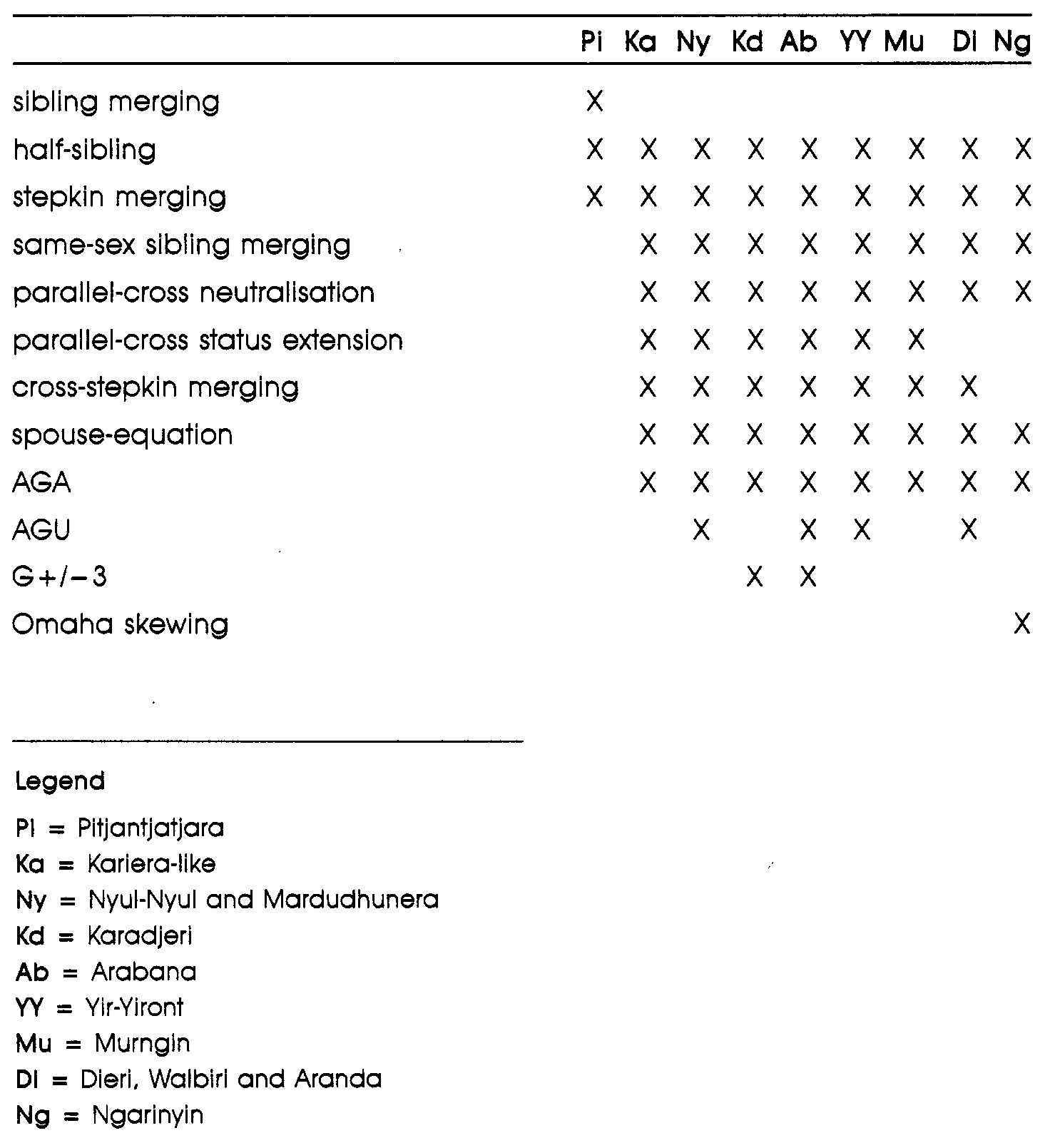

Scheffler analyses Pitjantjatjara, Kariera-like systems, Nyul-Nyul and Mardudhunera, Karadjeri, Arabana, Yir-Yiront and Murngin, Warlpiri and Aranda, Dieri, and Omaha-like systems. Differences among these systems are, he believes, secondary to, and in part based on, the common structural features. The varieties of Aboriginal kin classification analysed are based on the same components, and there is little variation in the principal classes, in Scheffler’s opinion. Table 1 contains a summary of the typology resulting from the posited extension rules.

In my view Scheffler is led to underestimate the differences between systems such as the Kariera and the Murngin through his focus on equivalence rules and the analysis in terms of superclasses,2 Furthermore Rumsey (1981) provides data inconsistent with Scheffler’s inference of certain superclasses in Ngarinyin kin classification.

Table 1 Extension rules characteristic of Australian systems of kin classification (after Scheffler 1978).

Linguists and anthropological linguists have contributed greatly to our knowledge of the variety of modes of kin classification, and to their use In context, as well as behaviour governed by kin relations such as avoidance codes. Several such studies have recently been brought together into a volume edited by Heath, Merlan and Rumsey (1982). Kin relations are reflected in syntax, especially the structure of personal pronouns. Hale (1966) finds that agnation and the principle of alternating generations play a role in the syntax of some Australian languages. His examples include noun phrase reduction and the structure of pronouns which, among other things, distinguish first person dual agnate from first person dual non-agnate (Hale 1966, 324). Schebeck (1973) and Hercus and White (1973) discuss the association between pronominal series and various kin terms. For example, one series is used to denote persons in the speaker’s own, grandparent’s, and grandchild’s generation, contrasted with the speaker’s parent’s and child’s generation. Another series is used for persons in a father-son relation (Hercus and White 1973 , 55-56). In Panyjlna, first and second person pronouns encode kin relationships and categorise them. For example the loss of distinctions between inclusive and exclusive In part of the first person paradigm, and non-use of pronouns in parts of the second person paradigm, reflect respect and avoidance rules (Dench 1980-82), Kaytej personal pronouns are marked for categories of kinship, a feature also of the closely related Arandic languages (Koch 1982).

Relations which entail avoidance or respect provide the motivation for special codes. The relation between brothers-in-law is marked by a restricted vocabulary in Guugu-Yimidhirr (Haviland 1979a, 1979b). Some everyday words survive in brother-in-law vocabulary, whereas in some cases everyday words are replaced by multiple service words, and in others brother-in-law words have no everyday equivalent. In Gurindji avoidance relationship is also the motivation for the reduction In the number of simple conjugable verb stems to one, and the deletion of the second person pronoun (McConvell 1982). Rumsey (1982) reports similar vocabulary reduction in the Bunaba avoidance language gun-gunma. Sutton (1982) shows that a degree of respect and circumspection is characteristic of all kin relations in Cape Keerweer, especially between close relatives, and this is reflected in linguistic usages. Features similar to avoidance languages are exhibited in other special languages. In the dhamin auxiliary language of the Lardil, formerly taught to subincision initiates, lexical Items are more general and abstract than in ordinary Lardil. Kin terms are reduced to five, constructed partly on section and partly on subsection principles (Hale 1982).

The use of kin terms themselves depends on the context. Rumsey (1981) found that the Ngarinyin term ‘mother’ can be used to refer to all women of the opposite moiety. The merger of generations tends to occur in the context of discourse about interclan relations. Rumsey Infers that there is no single structure for the Ngarinyin terminology. Anthropologists have recorded basic terms of reference and address. Linguists have reported a degree of flexibility and polysemy hitherto unrecognised; for example in Heath’s (1982a) detailed linguistic data on the use of Yolngu kin terms. Several linguists have reported other series, including dyadic terms of the type ‘fatherand-child’ (Heath, Merlan and Rumsey 1982), and altercentric terms of the type ‘your mother’ (Merlan 1982). Kin terms can sometimes be shown to be the etymological basis for social categorical terms such as kirta and kurtungurlu in Waripiri and other semi-desert languages (Nash 1982). Such categories were analysed in terms of a descent framework at the beginning of our period.

DESCENT

The concept of descent line is a crucial component of Radcliffe-Brown’s synthesis, providing as it does the conceptual link between the mode of kin classification, marriage rules, and the structure of the local group. He also believed the clan, and by derivation the horde, to be universally a patrilineal descent group, as have many Australianists until recently (eg Berndt and Berndt 1964, Stanner 1965, Turner 1980a). Several issues focused on descent have been prominent in the literature over the last quarter-century: the confusion of a line of descent with a lineage, descent group or some other kind of group; the question whether Aboriginal land holding units are appropriately labelled descent groups at all; and the degree to which they are corporate.

By a ‘descent line’ Radcliffe-Brown (1951, 1956) simply meant a sequence of kin categories as shown on a diagram, and not a social group, although descent lines were related to social groups or categories (Barnes 1967, 31; Scheffler 1978, 43-51). Others such as RM Berndt (1955), Meggitt (1962, 201) and more recently Morphy (1978) have used this expression, or a related expression such as ‘patriiine’, to refer to a type of social group. Some have taken sequences of terms on a kinship diagram to represent a definite number of descent groups related by marriage exchange (Lawrence and Murdock 1949). Radcliffe-Brown’s early criticism of these trends (1951, 1956), has been reiterated more recently by Piddington (1970) and Shapiro (1981).

Is the term ‘descent’ appropriately applied to Aboriginal social groups? Australianists have used the term in different ways. Some have followed Rivers to mean filiation that confers group membership, or through which rights and duties are transmitted, but which does not imply descent from a common ancestor (eg Reay 1962-63; Hiatt 1965; Turner 1980a, iii). Others have implied that the group is defined by descent from a common ancestor (Berndt and Berndt 1964). Shapiro (1967a) introduces the distinction between absolute and relative affiliation, equivalent to direct and indirect descent. Yolngu patrimoieties are recruited by relational affiliation, on the evidence that the child of an incestuous union is of the opposite moiety from that of the mother. Fortes (1969) assesses Warlpiri descent lines as successive degrees of kinship reckoned by steps of patrifiliation and matrifiliation. The patriline, but not the matriline, has more definite descent attributes, and ‘some rudiments of corporate structure’ (Fortes 1969, 117).

Piddington (1970) does not dispute the applicability of the term ‘descent’ to Aboriginal Australia; however, Scheffler (1973a), who has advanced a refined set of criteria for the application of descent concepts, argues that Warlpiri patrilines and patrilodges are not descent groups or patrilineages, because they are not defined with reference to ancestors. They are rather ‘patrifilial kin groups’ (Scheffler 1978, 522-23). Aboriginal concepts of kinship are grounded in concepts of bisexual reproduction, but the kin links postulated between human and Dreamtime Beings are ‘metaphoric’, Western anthropologists have found it all too easy to understand egocentric kin categories as lineally defined or descent ordered categories. The central error in Radcliffe-Brown’s thinking about Australian Aboriginal society was ‘that he failed to realise that even the “patrilineal clan” is a kind of kin class’ (1978, 524). His ‘descent lines’ are not the categories on which Australian systems of kin classification are based, but are structurally derivative, and dependent on rules of kin class definition and expansion. He was right, however, to insist that in Australia social structure is equivalent to kinship (1978, 524).

A comparison of eastern Warlpiri and Yolngu clans reveals something of the variability in the constitution of Aboriginal social groups. Some eastern Warlpiri adults are hazy about genealogical links even among members of their parents’ generation; what is important is that members of a clan have a set of fathers’ fathers, and fathers’ fathers’ sisters (see also Myers 1986). By contrast, whereas Yolngu clans are not all bounded by common descent from a human ancestor, so that ‘patrifilial kin group’ is a happy description, descent constructs are important in the definition of personal identity as well as lineage and sublineage identity for some clans, through the inheritance of names from a common ancestor, In his last paper Radcliffe-Brown (1956, 365) writes:

The clan is corporate in the sense that its adult male members can and do engage in collective action, and that as a clan they have collective ownership and control of a certain territory with its food resources and its ‘totem centres’ with their associated rites and myths...A woman belongs to her father’s clan but to her husband’s horde.

The corporateness of patrilineal land holding units has been questioned by Piddington (1970) and Shapiro (1981). Shapiro allows that Yolngu (‘Miwuyt’) sibs have some degree of corporateness, but not the totemic unions or linguistic groups Into which the sibs are grouped (Shapiro 1981, 24). The group of sisters’ sons of a clan is important in clan affairs, so that one must either accord the sisters’ sons of a clan some degree of corporateness, or deny that of the sib (1981, 104). Furthermore the articulation of the kin terminology with the patrilineal groups is limited.

The question of corporateness is essentially about control as well as the definition of group and category identity and inter-relations. Moreover, It is a question that can only be answered for each particular case. The recent literature on land claims displays variations, for example, in the rights of children of women of a clan as against the clan members (Hiatt 1985).

Recent ethnography has shown the assumption, that land holding units are universally patrilineal, to be false. Layton and Rowell (1979) and Layton (1983) describe Pitjantjatjara groups as ambillneal. Pintupi groups have the structure of bilateral kindreds according to Myers (1976, 1986). The membership criteria of Western Desert groups include principles other than descent or filiation: birth on an estate; conception at an estate; father’s membership of the group; mother’s membership (less frequently stressed); and the estate in which a man is circumcised (Tonkinson 1978a). Every individual is entitled through these principles to membership in more than one estate group through bonds of shared spirit and substance (1978a, 52). This account is consistent with RM Berndt’s assertion that In the Western Desert region there is only a ‘bias toward patrilineal descent’ (Berndt 1959, 96), an assertion made despite representing Western Desert local organisation in terms of patrilineal local groups.

The application of the term ‘descent’ has exercised anthropologists and lawyers in the course of Aboriginal land claim preparation and hearings pursuant to the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, for the expression ‘local descent group’ forms part of the definition of ‘traditional Aboriginal owners’ in the Act. The resulting debates have no doubt influenced academic anthropological discourse, if only indirectly, but I do not consider the debates themselves here for they arise out of the complex matter of the legal application of anthropological expressions (see Hiatt 1984a; Maddock 1982, 1983).

There is a close relationship between the paradigm in which descent is a core concept, and the alliance approach, in which, in some interpretations, marriages constitute exchanges among male members of descent groups.

ALLIANCE

Those who have discussed or applied the alliance approach to Aboriginal kinship have done so from various points of view. The main interpreter of a structuralist approach to kinship into English speaking anthropology has been Needham. Early in our period Needham (1960) refuted Livingstone’s representation of Ungarinyin kinship as based on alternating exchange, and continued his attack (Needham 1962a, 1962b, 1963a) on the theory of Homans and Schneider (1955). These authors had argued that Lévi-Strauss’s theory of cross-cousin marriage was an example of an explanation in terms of ‘final causes’ (ie functions), but that this was insufficient to explain the adoption of an institution, which must be explained in terms of ‘efficient cause’ (ie motivation, Homans and Schneider 1955, 16). Homans and Schneider attempt to show the motivation behind various forms of cross-cousin marriage. In patrilineal societies the father-child relation is marked by respect and constraint, whereas the mother-child relation is characterised by warmth and nurturance. These sentiments are extended to other close kin of each parent respectively. Matrilateral cross-cousin marriage is appropriate in patrilineal societies because of the extension of sentiments to the mother’s brother and to her daughter, reflected in patterns of visiting and so on, and the converse case is found in matrilineal societies. Needham (1962a) attempted to refute the argument by collating evidence inconsistent with the theory, especially on Purum kinship.

As for Australian kinship specifically, Needham (1962b, 1963a, 1963b, 1965) interprets McConnel’s and Thomson’s reports of Wikmunkan kinship and marriage in order to represent the system as a two-section system of prescriptive alliance, and In the same context questions the position of Homans and Schneider (1955, 1962) on the genealogical basis of kin categories.

One who was astonished at all the heat generated over unilateral cross-cousin marriage was the Marxist anthropologist FGG Rose, whose main contribution to Australian studies has been to relate the demography of kinship to material relations. Rose (1965) explained matrilateral cross-cousin marriage as arising from the age difference between husband and wife (see also Rose 1960a). Leach (1965 ) replied that a statistical fact cannot convert into a jural rule; structuralists were concerned with the latter. (Leach thus reveals a structuralist’s difficulty in conceiving material conditions for, or effects of, rule governed action.) Goodale (1962) had made a similar point to that of Rose in her explanation of why the choice of Tiwi women was limited to a FeZS as their first husband. This was accounted for by the average twenty year age difference.

Needham (1966) sought to refute Rose’s hypothesis that gerontocracy led to the abandonment of bilateral cross-cousin marriage; the conclusion was valid only for first cousins, he thought, and Rose’s own data show no disparities between the ages of patrilateral and matrilateral cross-cousins. However, de Josselin de Jong (1962) had already pointed out that the MBD category included ‘mothers’, and the FZD category included ZDs, which could account for any unexpected similarities of age.

Hiatt (1962, 1965) questions the empirical validity of Lévi-Strauss’s theory with reference to his Gidjingali data. He shows that a model of exchange among four groups, derived from de Josselin de Jong’s (1962) account of Lévi-Strauss’s theory, ‘has no bearing on the realities of kinship and marriage among the Gidjingali’ (1965, 129). In a response to Fox (1967), Hiatt (1967, 472) examines Gidjingali bestowal rights and actual exchanges and finds that:

any attempt to explain Aboriginal kinship systems in terms of sister- or daughter-exchange, either between individuals or in the sense of reciprocal arrangements between patrilineal descent groups, would seem to have a fairly weak empirical foundation.

In another paper Hiatt shows that only a small percentage of Gidjingali men managed to marry women to whom they had rights (Hiatt 1968, 168), but concedes the following: that the people had a definite notion of reciprocity between individuals with regard to marriage; that marriage rights were defined partly in terms of clan membership; and that men occasionally spoke of traditional exchange relationships between clans (1968, 172). However, patrilineal groups did not engage as groups In exchange transactions; rather, niece exchange was a contractual arrangement between individuals, so that assertions of traditional exchange relations must be taken as a ‘half-formed ideal of how the system should work’ (1968, 173).

In his reply to Hiatt, Fox (1969) argues that Hiatt takes too narrow a view of Lévi-Strauss. It is immaterial what the actual units of the system are. Whatever the units, the way In which women are ‘exchanged’ in Australian society is ‘elementary’, and usually direct, but with Murngin type systems having features of direct and generalised exchange (1969, 17). All this is not to say that formal groups are always the agents of exchange in Fox’s view. Despite these remarks, Fox (1967) represents Aboriginal marriage as a matter of exchange between descent groups, kin relations being secondary in determining marriages (1967, 186). The ‘operators’ are local lineages (1967, 218). Shapiro’s (1981) account of Yolngu kinship challenges such a model (see below).

Lévi-Strauss (1969b) used the Birdsell defence against Hiatt (1968)—the Gidjlngall are ‘a collapsing Australian tribe’—and backed it up with the Leach stratagem; he was concerned only with the rules, which ‘have their own life’. Hiatt (1968) countered with the information that the Gidjingali have two kinds of marriage rules, those expressed In terms of general categories, and those in terms of genealogical specifications. Lévi-Strauss’s theories were based on the former.

Like Hiatt, Sackett (1976) tests alliance assumptions against Australian data. Restricted exchange is inadequate to account for Western Desert marriage, where men marry a somewhat distant cross-cousin, and patterns of marriage are somewhat asymmetrical. Indirect exchange is the rule, and direct reciprocity impossible (1976, 174). According to Sackett’s explanation, the wide ranging social network resulting from distant marriage overcomes difficulties in times of poor resources and drought.

It was Maddock (1969a) who brought structuralism directly into Australian anthropology, but his version of alliance theory, like Leach’s (1961), is rather more concrete than that of Lévi-Strauss. The functions of wife-bestowing, wife-yielding and wife-receiving are disposed in various ways among descent groups. In patrilineal societies wife-bestowers and wife-receivers will be in the same moiety, so that contrary to Leach (1961) exchanges take place between groups of the same moiety, and by individuals of both sexes (Maddock 1969a, 24). In a later work Maddock (1972, 69) develops the link between ritual and affinal ties, arguing that ‘the relation set up by marriage in one generation continues in the next as bestowal and management’. In this as well as a later revision of the same book (1982), clans or sibs remain important as the basic units of sociality (1982, 76).

Morphy (1978) takes up Maddock’s scheme to represent Yolngu marriage as an exchange between clan subgroups within the moiety, with the exception of ZDD exchange. Keen (1986) finds that Morphy’s notion of ‘agreements’ between MM and ZDC subgroups of clans does not fit the facts at Milinglmbi. The affinal network among clan subgroups can equally be explained In terms of sons’ rights following from the marriages of their fathers.

The Dierl case was regarded as anomalous by Levi-Strauss (1949, 260-62), that is, as a transitional type between generalised and restricted exchange. By representing the terminology in terms of matrilines rather than patrilines, Korn (1971) claims to demonstrate similarities between the Dieri and Aranda systems.

A strong critique of both descent and alliance views of Aboriginal kinship and marriage, especially those of Leach and Maddock, is advanced by Shapiro (1981) in a study of Yolngu ‘affinity’. Both Leach (1961) and Berndt (1955) emphasised local corporations allied asymmetrically (Shapiro 1981, 1-2). Contrary to Maddock’s claim (1969a, 24; 1974, 71) that each patrilineal clan stands at the centre of an exchange network the other elements of which are also patrilineal clans, the transaction is indeed part of an exchange network, but its elements are Individuals and aggregates of matrikin’ (Shapiro 1981, 102). Shapiro presents an alternative analysis of Yolngu kinship based on the concept of the ‘endogamous kindred’.

In Shapiro’s analysis, the endogamous kindred, which cross-cuts clan membership, is the basis of Yolngu affinity as well as residence. Marriage alliances take place between groups of matrikin or ‘matrilines’ and the ‘local collectivity’ within the kindred is ‘encoded’ into a four-fold ordering of clans in a semi-moiety system (Shapiro 1981, 152-54). However, the concept of ‘endogamous kindred’ presents some problems, for Shapiro confuses the egocentred kindred with a sociocentred cognatic network when he remarks that the marriage clusters described by White (1976) are more or less identical with locally endogamous kindreds (Shapiro 1981, 155). Moreover the idea that a residence group could be based on a ‘single kindred’ is quite incoherent unless the group is either wholly endogamous, or it coincides with the kindred of a single member or group of full siblings.3 Nevertheless, the focus on cognatic kin networks is an important corrective to more clan oriented accounts. In contrast, Kupka and Testart (1980) offer an account of Yolngu marriage as a matter of exchange among clans and clans-aggregate.

David Turner (1980a) uses an alliance framework to construct a typology of Aboriginal kinship systems. Turner assumes the universality of bilateral kinship in Aboriginal Australia, the universality of patrilineal land owning groups, and that ‘an exchange of spouses between groups is desired even though it may not always be practised’. Turner’s thesis is that Australian systems of kinship and marriage reflect different alliance arrangements between land owning groups reckoned over a culturally defined genealogical grid’ (Turner 1980a, ii). Inter-relations between cognatic relatedness and relations to the patrigroups of cognates, as well as membership of one’s own, determine the classification of kin. Turner constructs models of Aboriginal systems of kinship and marriage in terms of ‘patrigroup families’, that is, members of patrigroups linked through marriage, and constructs a typology based on these models.4 Two extreme theoretical possibilities of marriage alliance are postulated. At one extreme the members of a patrigroup may choose to marry only their own members, their ‘closest’ relatives, precluding the possibility of fraternal alliances, but achieving the greatest solidarity. At the other extreme, the men of a patrigroup may decide to marry into a group with no previous affinal relationship with their own, that is they would avoid marriage into their cognates’ patrigroups, achieving the most comprehensive network. Each marriage precludes future affinal alliances between the same groups (Turner 1980a, xi). Most Australian peoples have opted for solutions somewhere in between. Although the universality of Turner’s postulates is questionable, his scheme has interesting implications for the kinds of social networks associated with different kinship systems.

The value of formal and mathematical models of marriage ‘exchange’ systems, such as the group-theoretical model by Tjon Sie Fat (1981), or those of Liu (1970), is hard to assess, but It seems clear that alliance theory has advanced understanding of Aboriginal marriage systems through a process of conjecture, modification and refutation. It would be helpful now to return to Lévi-Strauss’s original vision, and analyse bestowal and marriage within Aboriginal exchange economies as wholes.

BESTOWAL RELATIONS

One by-product of the alliance debate has been the discussion of agents and relations in marriage arrangements. Data on the nitty-gritty of the politics of bestowal are hard to come by—the richest account of conflicts over bestowals, from the point of view of men at least, remains that of Hiatt (1965). Maddock’s (1969a) differentiation of bestowal functions, defined in terms of group rights, has also been influential, The main contribution of Shapiro, who has focused rather on networks of matrikin (cf Peterson 1969), has been the elucidation of mother-in-law bestowal (Shapiro 1971), which, as with ZDD exchange (Shapiro 1968), he was the first ethnographer of the Yolngu region to document.

Piddington stresses the distinction between egocentric networks and sociocentric groups. The former, but not the latter, are Involved In marriage arrangements which entail individual obligations; the latter are concerned with ceremonial, economic and political affairs, which entail reciprocal obligations (Piddington 1970, 338-39). Discussion has also focused on the relative roles and powers of men and women in marriage arrangements (Hamilton 1970, 1981; Bell 1983). For example Hamilton (1970) examines women’s accounts of the agents in marriage arrangements in northcentral Arnhem Land. No woman admitted being able to bestow her own daughter, and women nominated a variety of relatives including the bestowed girl’s mother’s mother, other women of the matrigroup, men of the girl’s patrigroup, and the girl’s father (the predominant nominee of bestowed girls themselves). Older women were more likely to nominate a member of the matrigroup.

THE AGE FACTOR IN MARRIAGE

We have already encountered the suggestion that age factors should be taken into account in the explanation of matrilateral cross-cousin marriage. Discussion from this perspective has links to historical materialism, which articulates political, economic and social structural factors. At the beginning of the quarter-century Rose (1960a) made his seminal contribution to the topic which has become known, rather inappropriately, as ‘gerontocratic polygyny’, reviewed by Hiatt (1985). Rose (1960a, 1968) examines the implications of the large difference in the ages of husbands and wives on Groote Eylandt, and explains the assumed evolution from group marriage to pairing In terms of the invention of the spear, and polygyny as serving the needs of women during the child-rearing period. Older men were able to sustain their monopoly of wives through the initiation of young men.

The classic ethnography of gerontocratic polygyny is that of Hart and Pilling on the Tiwi (1960). Goodale’s (1971) study of Tiwi women does not so much contradict Hart and Pilling’s account as complement it. Old men did control the distribution of women as wives, but Hart and Pilling missed the importance of a Type A contract between a woman, her father, and her daughter’s potential husband. They focused on the Type B contract between a man and his daughter’s husband, which could only be made if the Type A contract had expired (Goodale 1971, 54).

Some doubts have been cast on the validity of aspects of Rose’s theory (Maddock 1972, 72); nevertheless, some scholars have accepted and elaborated on the connection proposed between initiation, the authority of elders, and polygynous marriage. Maddock (1972, 72) proposes that young men remain single because of the promise of religious gratification through a long induction into the religious life, in which ‘the power of the elders acting in concert is deeply impressed on them’. Were women to go through a similar period of instruction, their marriages too would be delayed, and so age related polygyny on any scale would be impossible. The older men therefore exclude women from the Initiation ceremonies. The doctrine of the structural and historical unity of society and nature imparted in the cults gives social norms a firmer hold (Maddock 1982, 141). The religious separation of males and females does not entail polygynous marriage (as suggested in Keen 1978), and the Tiwi case is problematic. Tiwi males and females both move through religious induction, yet they have a rate of polygynous marriage which is among the highest recorded for Aboriginal Australia. The contrast is not as clear as Maddock believes, for even in systems where only men are inducted into age grading rituals, there is no necessary reason why a young man could not also marry. In Tiwi society there was no clear correlation between ritual induction and the age of marriage (Goodale 1971). The connection between religion and polygyny is rather that the authority of the elders and the apparent cosmic necessity of the norms, are established through the religious life, which the older men control.

Keen (1978) argues that older Yolngu men, the main beneficiaries of polygynous marriage, require some means of preventing the young men from marrying women of their own age. This is achieved through a complex system of betrothal, and through the authority of older men, based on their imputed control of, or access to, supernatural powers in the major ceremonies, and control of esoteric religious knowledge. Furthermore, no advantageous alternatives are (or were) available to the young. Older men do not have powers of command to any extent outside a ritual context; it is rather that young men in general do not actively prevent older men from having young wives (1978, 377-78; see also Keen 1982; Hiatt 1985).

The degree of polygyny varies greatly among Aboriginal communities. Meggitt (1965) explained the differences among three Warlpiri communities as being due to differences in the degree of acculturation. Long (1970) extended the comparison to include a number of Northern Territory Aboriginal communities, and found that length of contact did not explain the variation; other factors must also be considered. The difference in the degree of polygynous marriage between the Gidjingali and the western Yolngu arises from differences in the systems of kin classification and the ethic of generosity, according to Keen (1982). Some older Yolngu men are able to acquire many more wives than any Gidjingali men because the Yolngu mode of kin classification determines an optimum age difference between potential spouses; whereas the form of the Gidjingali system of kin classification explains why women over whom Gidjingali men have claims are so seldom of marriageable age. A positive feedback effect is also posited, for the success of Yolngu men in marriage is a condition for the rapid growth of clans, and in turn, males of large clans are better able to press their marriage claims.

But how are these relations and processes articulated within the social order as a whole? In Bern’s (1979) Marxist account of power differences between men and women, the elaborate structure of men’s cults as well as the men’s control over the access of young men to secular and religious knowledge, and to wives, effectively deprives women of political equality or economic autonomy.

These discussions tend to assume that polygyny is only In male interests. In an early paper on women of northern Arnhem Land Hamilton (1970) argued that polygyny was in the interests of older women as well as men. Because older men monopolised the younger women, the older women had access to the younger men. This perspective implies that polygyny is not necessarily an index of male domination. However, in a later paper Hamilton (1981) contrasts Arnhem Land with eastern Western Desert marriage. Arnhem Land polygynous marriage provides the basis for the financing of men’s ‘ritual extravanganzas’, for an older man can obtain younger wives as labourers, relinquishing earlier, or even altogether, the need for the labour of daughters and sons-in-law. The presence of an autonomous women’s ritual life in the eastern Western Desert is a powerful deterrent against polygyny. Women have rights regarding marriage arrangements and to determine their sexual transactions with men.

The age factor in Aboriginal marriage motivates the ‘double helix’ model of Alyawarra marriage proposed by Denham and others (1979). The authors construct a diagram of Alyawarra kinship terminology with patrimoieties, matrimoieties and subsections superimposed, although these are only implicit in this system, and find that the model does not altogether predict kin term assignments in Denham’s data. The authors assume a mean age difference between husband and wife of fourteen years, with the husband older, and hence a patrifilial generation 1.5 times as long as a matrifilial generation. They then construct a model based on the Kariera system, of marriages between categories of genealogical kin representing the resultant age differences two-dimenslonally, showing in effect which categories are within marriageable age range of one another. In the model, patrilines and matrilines are not coordinated, and generations are fuzzy. Sibling exchange is precluded by the age bias, and so the Kariera model becomes a system of indirect exchange. In the opinion of the authors the model ‘seems to accommodate better most available data concerning both the ideology and the practice of central Australian descent, marriage, and kinship’ (Denham, McDaniel and Atkins 1979, 1).

This article drew a number of critical responses (Martin 1981; Scheffler 1980, 1982; Turner 1980c). For example, Scheffler (1980) comments that Radcliffe-Brown neither authored nor endorsed the first model, and that models of this kind represent logical relations among categories. Denham Imposed the arbitrary demand that people supply only one term for each relative, and did not ascertain the basis on which a term was supplied. Many of the anomalies are thus a result of defective methodology. Scheffler (1982) adds that the notion of a ‘best term’ is ethnographically unsound, and that the authors do not show how the double helix model accounts’ for the data. Certain apparent inconsistencies in reciprocals could be due to superclass-subclass relations (Scheffler 1982, 180-81). The article also inspired a formal mathematical treatment by Tjon Sie Fat (1983), a model which generates varieties of helical structures ‘with age-biased matrilateral cross-cousin marriage’ by mapping age structure onto a group-theoretic model of generalised exchange.

Paradoxically, models such as the double helix appear to be too simple, for incumbents of a given kin category in relation to Ego are traced through a variety of genealogical and other links. Given the differences between matrifilial and pafrifilial generations, the range of average ages of incumbents of certain categories in an Aranda type system traced by different genealogical routes varies greatly (see Keen 1982). There does seem to be a consensus through the period that marriage is not regulated by what used to be called ‘marriage classes’.

SECTIONS, SUBSECTIONS, MOIETIES AND SEMI-MOIETIES

Discussions of class systems have revolved around several issues: the nature of the relations among the classes, and between them and kin classification; their descent basis; their functions; the demographic conditions for their operation; their role as relations of production; and the question of their origins.

At the beginning of our period Hammel (1960) constructed a formal seven-fold typology of section and subsection systems. Theories of the derivation of class systems were summarised by Service (1960), According to Lawrence and Murdock (1949) and their precursors, four section systems arose from the intersection of matrilineal and patrilineal descent groups, and subsections from division of sections through a particular marriage rule. Lane and Lane (1962, 50) on the other hand, see sections as resulting from the moieties bisecting sibs of an opposite linearity. Service (1960) and Fox (1967) argue against this ‘double descent’ theory. Indeed, in retrospect such theories about the production of more complex categories from the intersection of simple ones seem to say more about the properties of synthetic models than about the origin of the systems.

Models, too, are often overgeneralised. Hence Reay (1962-63) argues that, contrary to Radcliffe-Brown, the simultaneous occurrence of matrilineal and patrilineal moieties is not ‘a necessary concomitant of a subsection system’ (Reay 1962-63, 97; Radcliffe-Brown 1929, 199; 1930-31, 39); and the unnamed patrimoieties of the Anyula are an ‘abstraction’ (Reay 1962-63, 98). Scheffler points out that not all societies with section systems have patrimoieties, matrimoieties and generation moieties, so that even if these gave rise to the systems, they are not now structurally dependent on them. He offers a theory of the origin of Australian class systems in kin ‘superclass’ categories. The unnamed moieties of Warlpiri society, like the Kariera and Aranda are ‘nothing more than fairly complex kin classes’ (Scheffler 1978, 522). Both Dumont (1966) and White (1981) see alternating generation categories—generation ‘classes’ on the one hand, and generation moieties on the other—as irreducible features.

Shapiro (1967b) extends the expression ‘semi-moiety’ to the quadripartite classification of sibs (1967b, 467), and attributes such a system to the Yolngu. This view is elaborated in two later works (1969, 1981). The imputation by Shapiro of semi-moieties to the Yolngu has been questioned by Berndt (1976), Morphy (1977) and Keen (1978, 1986) who found Shapiro’s view inconsistent with their data. Similarly Heath (1978, 1980) questions the existence of named patrimoieties attributed to the Mara by Spencer (1914), and of necrophagous and ceremonial moieties attributed to the Mara by Maddock (1969b, 1979), on the basis of recent linguistic fieldwork with a Mara informant. Maddock argued that the Mara possessed an implicit but elaborate and symmetrical cognitive representation of their social order based on the principles of binary opposition and logical complementarity (Maddock 1969b; Heath 1978, 468).

Maddock and Heath make different inferences from Spencer’s incomplete and ambiguous record. Maddock questions the relevance to the period of Spencer’s fieldwork, of information from a living, if old, Informant. Heath questions the relevance of Maddock’s Dalabon fieldwork to the Mara. Perhaps the interesting questions which arise out of this debate are these. In what sense can ‘implicit’ moieties have any existence? And to what extent can structuralist constructs represent ‘cognitive’ categories of the people In question?

Some anthropologists have characterised moieties and semi-moieties as descent groups (Reay 1962-63, 95; Lane and Lane 1962, 47) although Reay denies this status to sections and subsections (1962-63, 99). Dumont regards descent as a misnomer (1966, 237), as does Scheffler (1978), in whose opinion sections and the rest are not marriage classes, nor do they have a descent basis.

Radcliffe-Brown (1930-31) asserts that sections and subsections have nothing to do with the regulation of marriage, a view with which Elkin (1964), Service (1960), Meggitt (1962) and Scheffler (1978), among others, agree. They serve rather to systematise and generalise kinship relations. Reay on the other hand believes that Yanyula subsections regulate marriages, and the members of semi-moieties own and control important ceremonies (Reay 1962-63, 98).

What, then, are the functions of subsection systems? Munn (1973, 21) suggests that the Warlpiri subsection system has a broad synthesising function. It is a code which ‘lays out the articulation of the basic principles of the social structure in a single framework’. It can be translated into egocentric kin relations, and expresses the relationships among and between descent groups, semi-moieties (subsection patricouples) and moieties. A useful generalisation about Aboriginal classification systems is made by Burridge (1973, 133), who stresses the ‘interdigital and crosscutting nature’ of classification schemes as they relate to humans, and as humans relate to features of the environment. No category has exclusive membership, and each category ‘groups together those who, in other situations, will be differently grouped’. Rivalry is balanced by cooperation, opposition by complementarity.

The question of the origins of these systems has a number of dimensions, including historical, linguistic and structural. Lane and Lane (1962, 47) hypothesise that moieties, which they characterise as descent groups, may arise as structural epiphenomena ‘by the combination of other features of social structure’. Such implicit moieties may remain unnoticed until other conditions call attention to their existence. As we have seen, Scheffler derives sections and subsections from posited kin superclasses, agreeing with Radcliffe-Brown and Elkin that the systems systematise and summarise kinship. McConvell (1985) uses linguistic evidence to show that Elkin’s (1970) hypothesis about the diffusion of the subsection system was substantially correct, to locate the area of origin, and to speculate on the emergence of another type of subsection system out of a form of marriage exchange.

Yengoyan (1968) explains the alleged correlations between varieties of section systems and environment, by calculating the number of possible eligible wives in systems with no sections, with moieties only, with sections, and subsections. He concludes that population size sets limitations on the operation of the systems, Meggitt (1972) on the other hand concludes from an examination of the Register of Wards of the Northern Territory, that intertribal demographic differences had no discernible effects on the presence or functioning of subsections, and that these are not necessarily concerned in the regulation of marriage.

Godelier (1975) bases a discussion of the relation between mode of production, kinship relations, family organisation and demographic structures on Yengoyan’s findings, and argues that kinship relations function simultaneously as infrastructure and superstructure, control the access of groups and individuals to the conditions of production and to resources, regulate marriages, provide the framework for politico-religious activity, and function as an ideology (Godelier 1975, 10). McKnight (1981), however, sheds considerable doubt on the validity of Yengoyan’s methodology and the reliability of his data. Yengoyan makes a number of questionable assumptions: that marriage classes are somehow an index of kinship and marriage systems; that the complexity of class systems reflects the degree of restrictions on choice of marriage partner; that most ‘tribes’ are endogamous; and that marriage is organised on the basis of local groups. Nevertheless, the questions of how different systems of kinship restrict marriage possibilities, and the demographic conditions under which the systems work, are interesting ones.

What of the way in which people in different kin relationships behave toward one another? This matter has been touched on In the review of the kin classification literature.

ASPECTS OF KIN RELATIONS

Several ethnographic studies (eg Berndt 1965, 1971) have continued the practice of reporting social norms and behaviour by looking at reciprocal kin relations in turn. Meggitt’s ethnography (1962) is organised in this way, and he treats the social norms in detail; however, the framework provides the context for a rich ethnographic study of interaction and conflict. Conflict, particularly among men over marriage bestowals, is the focus of Hiatt’s study of the Gidjingali (1965), reflecting the influence of the Manchester tradition, through his doctoral superviser John Barnes.

Some shorter studies have examined and attempted to explain particular aspects of kin relations such as joking relationships (Jackes 1969), and especially the mirrirri and mother-in-law avoidance. Mirrirri is an Arnhem Land custom in which a man attacks his sisters if someone swears, or alludes to sexuality in some other way, in their hearing. Warner (1937, 112) explains that a brother treats his sister as the culprit in order to prevent a rift in the kinship structure. Hiatt (1964) finds Warner’s functional explanation unsatisfactory, suggesting that the explanation should be sought in the stringent sexual prohibitions between brother and sister (Hiatt 1964, 125), The brother attacks his sister out of revulsion due to the sexual prohibition. People may believe that the two have had sexual relations, so that the attack In effect proves the brother’s lack of interest in his sister (1964, 128).

Such an explanation rests on unproven psychological suppositions, according to Makarius (1966, 149). The Murngin brother’s behaviour is an extreme case of a more general phenomenon, the ‘general aversion of primitive man to hear obscene language addressed to their sisters’, which causes a brother to throw spears. The consequences of Incest are deadly, and may be forestalled only by the spilling of blood, Makarius speculates. By classifying a sister as wakinngu, ‘without kin’, their blood ties with the rest of society are denied and they cease to be dangerous (1966, 150). If this is so, one wonders why the mirrirri is still necessary; furthermore, Makarius offers no explanation for the allegedly general aversion.

Hiatt (1966) replies that Makarius’s hypothesis is too broad, and points out that men do not always draw blood. But he agrees that his own theory does not explain why a man attacks his sister if he sees her copulating with her husband. He suggests that the swearing Inflicts suffering on the brother because he has been taught that it is shameful even to think about his sister’s sexuality. His sister is seen as the real cause of the pain (Hiatt 1966, 154).

A structuralist interpretation is offered by Maddock (1970b). The behaviour makes sense when it is understood as an element in a larger pattern. It helps to express a binary opposition, heightening the distinction between a sibling or FZC of the same sex, and a sibling or FZC of the opposite sex. (This relation is subject to a similar custom among the Dalabon.) The custom functions to stress that sisters and FZC are not marriageable (Maddock 1970b, 176). Burbank (1985) suggests that a man’s attack on his sister may be seen as the substitution of one form of aggressive expression for another. The woman is expected to run away, for a brother and sister are not supposed to fight, so that a man’s attack on his sister is like an aggressive attack on an object, and is not expected to lead to injury (Burbank 1985, 53-54). Mirrirri is an example of redirected aggression such as damage to school windows following aggression from a teacher.

More recently Hiatt (1984b) explains the sexual content of mother-in-law avoidance, as well as the element of shame, as arising in this way. A youth who has had a mother-in-law bestowed on him has a long time to wait for a wife. Meanwhile he behaves in one important respect like a husband—he gives her meat. A flow of sexual impulses in the same direction would threaten the uxorial interests of the father-in-law, and the mother-in-law might react favourably owing to the privations of polygyny. The imposition of avoidance protects the interests of her husband.

We turn now to a quite different topic, in which kinship articulates with other dimensions of the social order; that of local organisation.

THE LOCAL ORGANISATION DEBATE

Radcliffe-Brown posited a quite straightforward connection between descent groups and groups of people living together to exploit the land. I cannot trace the development of his ideas here, but by the time of his 1930-31 synthesis Radcliffe-Brown distinguished the horde or local group from the local patrilineal clan. In an earlier paper Radcliffe-Brown (1918) attributed ownership of land to the horde, but in a later work the clan had become a land owning corporate group (1956). Elkin (1964, 45) follows this model, more or less, but uses the expression ‘local group’ ambiguously. RM Berndt (1959) ascribes land ownership to the local group, identified as the patrilineal clan, as distinct from the horde. The horde has no territorial claims, and is localised only in a general sense (Berndt 1959, 104). Berndt and Berndt (1964, 42) contrast the local descent group (a term derived from Leach), united by common descent, with the patrilineal or matrilineal clan whose members may or may not share a common ancestor.

Hiatt’s (1962) influential critique of Radcliffe-Brown, made in the light of his and Meggitt’s then recent fieldwork, distinguishes ritual from economic relations to land. The horde as described by Radcliffe-Brown is not typical, nor is the patrilineal clan ubiquitous. The common residence group in many areas is not a horde but a community, including members of up to twelve patrilineal descent groups, and splitting up into smaller food seeking units each of which commonly includes non-agnates and whose movements are not constrained by territorial boundaries (Hiatt 1962, 285).

In his defence of Radcliffe-Brown, Stanner (1965) coined the much cited distinction between the totemic ‘estate’ of the patrilineal group and the ‘range’ of the ‘territorial group’ which has some members of a dispersed patrilineal group as its core members. Territorial groups have a strong tendency toward patrilocal and virilocal residence.

Birdsell’s (1970) assault on the ‘Sydney anthropologists’ brings evidence together to refute the existence of a large community as a residence group, but unconvincingly explains findings which do not support the Radcliffe-Brown model as due to social change (see also Piddington 1971).

More recent research suggests that both Birdsell and Hiatt were right and wrong, but in different ways: Birdsell was justified in questioning the replacement of the band or horde by large communities, but incorrect in adhering to the universal Radcliffe-Brown model of the horde and to the universal dialectal tribe; Hiatt was right to question the Radcliffe-Brown model, but his picture of large communities is misleading. Named communities seem to be loosely bounded regional networks rather than residence groups, or groups with common and distinct rights in land.

Peterson’s data (1970) on an Arnhem Land band suggest that composition varied over time and between bands. Each band had a core of one or two older men, living on their own clan estate with their families and young sons-in-law, as well as a wife’s mother in many cases. Variations in composition are accounted for by the developmental cycle of the domestic groups which made up the band. Shapiro’s data on several Arnhem Land outstations and settlement camps led him to conclude that residence groups are based primarily on affinal ties. Agnates will live together only if they can do so without violating their obligations to affines. Each residence group has a wide range of choice of residence sites, although there is a preference for residing in territory associated with a clan (‘patri-sib’) with which one or more of its members is linked by close kinship ties. Moreover individuals, Shapiro believes, are more or less unrestricted in the territories in which they may forage (Shapiro 1973, 379). A close examination of Shapiro’s data, in conjunction with Peterson’s and my own, shows that in outstations from the mid-1960s, the core of the band, that is those most closely related to the estate on which it is situated, are as likely to be living on their mother’s clan estate as their own. Blundell and Layton (1978) also suggest that men of the Kimberleys lived for periods on their mothers’ and wives’ estates, as did the parents of a newly betrothed woman. Alyawarra household clusters reveal a patrilineal core plus a variety of uterine kin and affines (O’Connell 1978).

Two other issues must be mentioned here. First, Maddock (1982) has questioned the attribution of land ownership to the patrilineal group, at the expense of uterine descendants of group members. Verdon and Jorion (1981, 100) make a similar point: members of totemic corporations have the strongest claim over land surrounding their totemic sites, but ownership is shared with others occupying the land, the strength of their rights depending on their ‘ontological distance’ from the ancestor-totem. This issue is related to the critique of the assumption that clans are corporate, and the relationship of the rights and action of the descendants of clan women (Shapiro 1981). The issue has also been a central one in the application of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, leading to much discussion of the definition and relative rights of ‘owners’ and ‘managers’ (Peterson 1981, Peterson and Langton 1983, Hiatt 1984b).

Second is the nature of the tribe. Burridge (1973) was hesitant over the use of the term ‘tribe’, which he considered to be an imposition on Aboriginal practices. Burridge preferred the expression ‘unspecified larger group’ (1973, 129). The issue is canvassed in papers collected in Peterson (1976); but the most cogent critique is that of Sutton (1982), who questions the validity of Tindale’s (1974) and Birdsell’s (1953) notion of the relatively endogamous, politically and territorially discrete dialectal tribe. In an examination of the relation between language, speech community and social network in Cape York Peninsula, he finds no structure resembling the ‘tribe’.

Finally, the terms in which local organisation has been discussed have been recently questioned by Myers (1976, 1986), who challenges the applicability of the Radcliffe-Brownian model of local organisation to the Pintupi. Their territorial organisation diverges markedly from models of Aboriginal land tenure which treat bounded groups as basic. Neither bands (or ‘hordes’) nor rules of group recruitment are fundamental. Pintupi residential groups can best be understood through the egocentric concept of ‘one countrymen’, those who potentially share a camp and cooperate in the food quest. Land owning groups overlap in membership and are bilateral in composition. People make claims to country on a wide variety of bases including conception, initiation, birth, father’s conception, mother’s conception, residence and death of a close relative (Myers 1986). Myers’ account reveals not only the results of a change in perspective, but also the degree of variation in Aboriginal relations to land.

SYSTEM CLOSURE, CULTURE HISTORY, AND SOCIAL CHANGE

Recent research, then, including that carried out in preparation of Aboriginal land claims, has revealed more variation in Aboriginal social organisation than was previously realised. This trend has been accompanied by a paradigm shift in social theory away from systems thinking; a trend reflected in the Australianist literature to a greater or lesser extent. This review began with the formal elegance and integrity of Radellffe-Brown’s models of Aboriginal kin classification, marriage rules and local organisation, characteristic also of Lévi-Strauss’s analyses of Aboriginal kinship systems. The best known example of anomalies thrown up by a systems paradigm is the ‘Murngin problem’, which so dominated discussions of Aboriginal kinship twenty years ago (see Barnes 1967, Maddock 1970b).

The problem arose out of certain assumptions about Aboriginal social organisation: that descent is primary; that kin categories are genealogical; that the system cannot be open ended; and that social life is organised through the subsection system (Burridge 1973, 141-43). The controversy arose also out of anomalies in the ethnography, especially differences in accounts of subsection organisation, and the lack of logical fit between the subsection system and kin classification. There was an assumption, then, that formal models of categories, as well as models of the articulation between different orders of categories, captured the essence of Aboriginal kinship systems which are, or ought to be, formally tidy.

The assumption of system closure and tidiness is no longer widely held however, so that rather than the Murngin problem being solved, all the other apparently more tidy systems have become dis-solved, as the debate over Alyawarra kinship, as well of the contributions of the linguists, suggest. This general process of dissolution in part reflects new data, as a result of new fieldwork techniques, such as the recording of discourse. But it also reflects a change of paradigm in social theory from a systems approach to a ‘structurationist’ perspective in which social life is pictured as a looser weave across the warp of time.

A more adequate representation of Murngin (Yolngu) kinship and marriage was nonetheless achieved through the ethnographic fieldwork of Shapiro, Morphy and Keen. Shapiro (1967a, 1967b, 1969, 1970a, 1971, 1982) clarifies differences in bestowal relations, and describes the relations involved in ZDD exchange, but confuses matters through inferring semi-moieties where there are none. Morphy (1977, 1978) shows that the network of marriage could be, and sometimes was, closed in a cycle involving six lineages (and not clans as Liu 1970 assumes). Keen (1978) demonstrates some of the complexities of the marriage network, and shows that kin terminology tends to determine the asymmetry of the marriage network at the level of the lineage, and more strongly at the uterine sublineage level. Marriage links between clans, however, are often reciprocal. Despite these contributions, some anthropologists continue to construct models of marriage exchange between subsections, even though Yolngu marriage is governed by kin relations (Jorion and de Meur 1980, Kupka and Testart 1980).

The studies reviewed up to this point are, for the most part, synchronic descriptions and explanations of current practices or reconstructions of past institutions. Since evolutionism went out of fashion, speculation about the historical development of forms of Aboriginal kinship and related institutions has been rare. But there has been some discussion.

I have already mentioned McConvell’s hypotheses about the diffusion of subsection systems. Two other culture-historical studies should be mentioned. Lucich (1968) combines a hypothetical developmental sequence in Kimberley kin classification and marriage rules with a causal explanation. The developmental sequence is from first cousin marriage in a society with two patrimoieties, through a variant of a four section system, or via matrilineal moieties, to classificatory MBD marriage corresponding to the Karadjeri system. WBD or WFZ marriage is the ‘efficient cause’ of the Omaha terminology, rather than a principle of descent group lineality. A change in the marriage rules will produce a change in terminology.

Testart’s design is more ambitious. In a short summary of his book (Testart 1981, see also Testart 1978) he finds that even when the symbolic associations of sections vary, when the variants are put together to form matrilineal moieties they show the same dual classification. The only way to account for this ‘astounding’ fact is that the same original matrilineal classification was subsequently bisected in varying ways to produce different quadripartite classifications, and subsequently regrouped to form patrilineal moieties. These hypotheses are based only on a few cases, but Testart supports them with a mathematically informed survey of similarities and differences among systems of classification. This purports to show that there are greater similarities within matrilineal classifications than patrilineal.

Blows (1981) has examined Testart’s use of evidence in some detail. She finds dubious Howitt’s assumption that the Kalabara were patrilineal, an assumption on which Testart relies (Blows 1981, 152); and finds Testart’s inference that Cherbourg tribes were patrilineal to be a misinterpretation of Kelly’s (1935) information. She also questions Testart’s coherence index for several groups. What Testart counts as patrilineal descent is often the relation of relative affiliation or indirect descent between sections.

Even If subsequent investigations justify Testart’s findings that there is greater coherence among classifications associated with sections in a matrifilial relation than those associated in a patrifillal relation, this is not direct evidence of the temporal priority of matriliny, but could have other explanations, such as that subsections in patrifilial relations are more often adjusted in the process of diffusion than subsections in matrifilial relations.

A number of anthropologists have examined changes in the practices of remote communities, as well as the significance of kinship among Aboriginal people in southern Australia. Several studies examine changes in marriage practices and kin classification. A higher proportion of Haasts Bluff men were marrying in their late teens and early twenties, according to Long (1970), and intermarriage of Pintupi people with other groups appeared to be increasing. Turner (1974) constructs hypothetical vectors of change on the basis of a contrast between formal definitions and the complexities of the application of terms. Section and kinship systems had changed little at Jigalong, although residence patterns had changed radically (Tonkinson 1974, 56). At Wiluna the new social environment had imposed limitations on people’s attempts to maintain their traditions (Sackett 1975). Fringe dwellers in Alice Springs have begun to change their reckoning of filiation, according to Collman (1979). In some families children were named after their mothers, legitimising the emergence of matricentric domestic groups.

Beckett (1965, 16) found in western New South Wales that people of the same origin tended to be concentrated in one or two main localities, and that people tended to live near at least some of their kinsfolk. There were some continuities In marriage rules, for mating with any consanguineal kin was regarded as improper; and obligations to share food and other goods with kinsfolk were strong (Beckett 1965, 17). Beckett (1967) reconstructs Maljangaba marriage, circumcision and avoidance practices from the memories of old people. A very generalised account of the changes in kinship is also provided by Calley (1969).

In Aboriginal communities of southeastern Australia most people preferred to reside in their home region and marry within it, according to Barwick (1978). They were distinct from other working class Australians in their retention of extended family ties, and residence in large, composite households. Certain traditional norms might regulate marriage choices, including the prohibition of marriage with close cross-cousins. Intermarriage with other ethnic groups was especially high in urban areas. The Aboriginal population of Adelaide in the mid-1960s, on the other hand, had a far lower incidence of marriage among adults than in the white population, and a higher rate of divorce and separation (Gale 1970). Beasley (1970, 185) found kin ties to be important among the Sydney Aboriginal population. People desired to live with relatives from their own rural area, and kin relations determined household composition and entailed obligations to provide hospitality.

CONCLUSIONS

Anthropological knowledge of Aboriginal kinship and social organisation has advanced considerably over the last quarter-century. There have been significant additions to ethnography. To mention only monographs, anthropologists have made substantial contributions to knowledge of Groote Eylandt, Warlpiri, Gidjingali, Murinbata, Gunwinggu, Tiwi, Western Desert, Kimberley, and Yolngu kinship (Rose 1960a, Turner 1974, Meggitt 1962, Hiatt 1965, Falkenberg 1962, Berndt and Berndt 1970, Hart and Pilling 1960, Goodale 1971, Thomson 1972, Tonkinson 1978b, Lucich 1968, Myers 1986, Shapiro 1981). Several scholars have contributed synthetic treatments (Maddock 1972, Shapiro 1979, Scheffler 1978, Turner 1980a).

Let me now return to the question with which we began—how far have Barnes’s and Meggitt’s hopes and fears been realised? Formal analysis of categories and rules has become less prominent in Aboriginal kinship studies, although it continues. The emphasis has Indeed swung more to a consideration of ‘how the system really works’, especially through the recent work of anthropological linguists. We no longer expect to find very neat patterns of closed systems. Nevertheless formal models have proved to be heuristically valuable, stimulating research and debate, despite the danger that they might be built on false assumptions. Furthermore, it is necessary to understand the logical properties of systems of categories and rules in order to examine how they are applied in practice. Sophisticated comparative studies such as that of Scheffler (1978), despite their apparent narrowness and formalism, will be of great value in constructing broader based comparative studies.