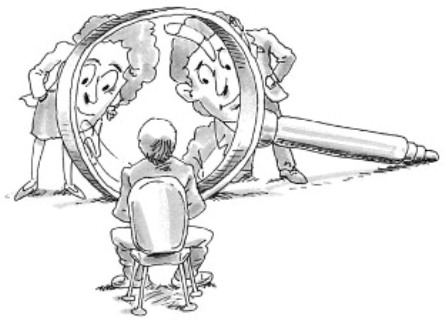

The Lens of Understanding

This chapter is about understanding ... the kind of understanding that will help you communicate effectively, prevent future conflict, and resolve current conflict before it gets out of hand ... the kind of understanding that results when you place your difficult person’s behavior under a magnifying glass, look through the lens, and closely examine the difficult behavior until you can see the motive behind it.

Did you ever wonder why some people are cautious and others carefree, some quiet and some loud, some timid and some overwhelming? Did you ever notice how one minute people might be trying to intimidate you, and the next minute they’re nice, and even friendly? Have you ever been astonished at how quickly people’s behavior can change from one moment to the next?

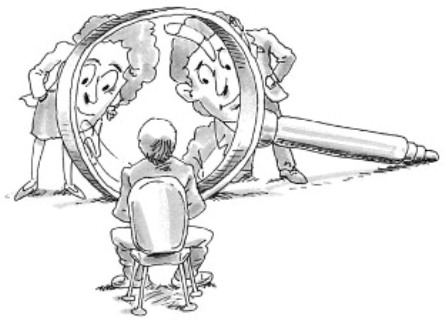

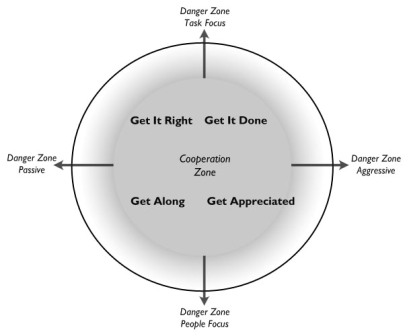

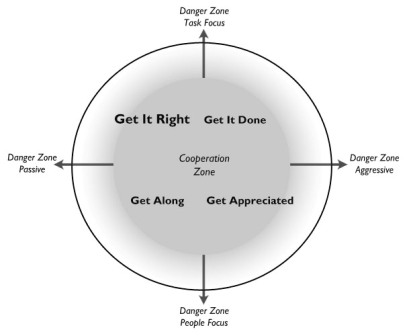

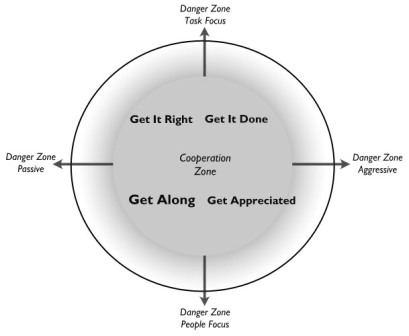

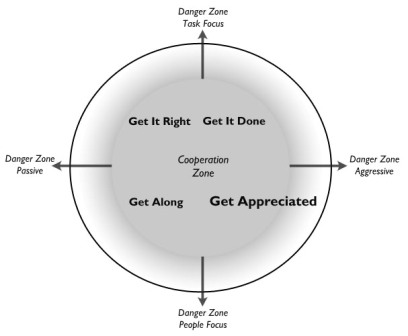

As you focus your Lens of Understanding on human behavior, first observe the level of assertiveness. Notice that there is a wide range from passive to aggressive, and most people find their own comfort zone within that range. Then observe the extremes. Passive, or nonassertive, reactions to a given situation can be submissive or yielding, and even complete withdrawal. Aggressive reactions to situations can range from bold determination to domination, belligerence, and attacks.

Everybody responds to different situations with different levels of assertiveness. During times of challenge, difficulty, or stress, people tend to move out of their comfort zone, and they become either more passive or more aggressive than their normal mode of operation. When challenged, a highly assertive individual might make his or her presence known by speaking louder or taking action faster. An individual of low assertiveness might be increasingly reticent about the same activities. You can recognize how assertive people are by how they look (directing their energy outward or inward), how they sound (from shouting to mumbling to being silent), and what they say (from making demands to offering awkward suggestions).

When you look through your Lens of Understanding, you can also observe that there are patterns to what people focus their attention on in any given situation. For example, have you ever become so absorbed in what you were doing that you forgot there were any people around?

When attention is focused almost exclusively on the task at hand, we call that a task focus. Have you ever been so caught up in what people were doing around you that you found it impossible to concentrate on anything else? When attention is focused almost exclusively on relationships, we call that a people focus.

Within this range and depending on the situation, behavior can quickly go from one extreme to another, from friendly and down-home, to getting down to the business at hand, or vice versa. During times of challenge, difficulty, or stress, most people tend to focus with greater exclusiveness on either the what (i.e., the task) or the who (i.e., the people) of the situation, rather than on their normal mode of operation. To discern people’s focus of attention, listen closely. When people are task focused, their word choices reflect where their attention is. “Did you bring the report?” “Did you finish your homework and chores?” “Do you have those figures?” “How close is that project to completion?” When people are people focused, their word choices reflect that. “Hey, how was your weekend?” “How’s the family?” “How are you feeling today?” “Did you see what I did?”

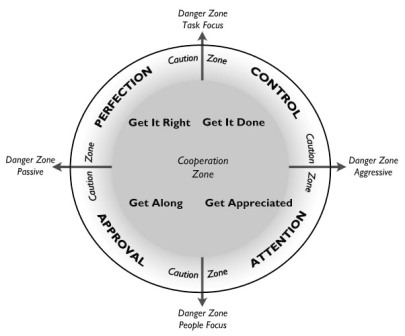

Now put it all together. People can focus on other people aggressively (e.g., belligerently), assertively (e.g., with involvement), or passively (e.g., with submission). People can focus on a task aggressively (e.g., with bold determination), assertively (e.g., with involvement), or passively (e.g., by withdrawing). These behavioral characteristics can be observed through your Lens of Understanding, in others and in yourself. All people have the ability to engage in a wide range of behaviors observable through this lens, sometimes dynamically, sometimes with a lot of static. Yet for each of us, there is a zone of normal—or best—behavior, and exaggerated—or worst—behavior.

What Determines Focus and Assertiveness?

Every behavior has a purpose, or an intent, that the behavior is trying to fulfill. People engage in behaviors based on their intent, and they do what they do based on what seems to be most important in any given moment. For our purposes, we have identified four general intents that determine how people will behave in any given situation. While these are obviously not the only intentions motivating behavior, we believe that they represent a general frame of reference in which practically all other intents can be located. As an organizational framework for understanding and dealing with difficult behaviors, these are the four intents:

Get the task done

Get the task right

Get along with people

Get appreciation from people

Just as people choose what to wear from a variety of clothing styles (e.g., formal-wear, office-wear, or weekend-wear), so people choose from a variety of behaviors that are situationally dependent. You may have a favorite shirt or pair of pants, and you may also have a behavioral style that you prefer. But rather than having one behavioral style all the time, your behavior changes as your priorities change.

You may find it helpful to identify these four intents in yourself and recognize their connection to your own behavior in various types of situations. This will make them easier to observe and understand in others.

Get the Task Done

Have you ever needed to get something done, finished, and behind you? If you need to get it done, you focus on the task at hand. Any awareness of people is peripheral, unless they are necessary to accomplishing the task. When you really need to get something done, you tend to speed up rather than slow down, to act rather than deliberate, to assert rather than withdraw. And when finishing a task is an urgent need, you may even become careless and aggressive, leaping before you look, and speaking without thinking first.

But it’s not only important to get it done. Sometimes it is more important to avoid making mistakes—to be certain every detail is accurate and in place.

Get the Task Right

Have you ever sought to avoid a mistake by doing everything possible to prevent it from happening? Getting it right is another task-focused intent that influences behavior. When getting it right is your highest priority, you will likely slow things down enough to see the details, thus becoming increasingly focused on and absorbed in the task at hand. You will probably take a good, long look before leaping, if you ever leap at all. You may even refuse to take action because of a particular doubt about the consequences.

Sometimes It’s a Matter of Time. Of course, it is important to find a balance between these two intents. We call that getting it done right because if it’s not done right, then it’s really not done, is it? But any number of variables can shift this balance. For example, if you were given two weeks to complete a task, initially you might lean more toward getting it right, and go slowly and carefully. As the deadline approached—and especially the night before—the balance could shift dramatically toward getting it done! You might suddenly be willing to make sacrifices in detail that before seemed unthinkable.

Get Along with People

Another intent behind behavior is to get along with people. This is necessary if you want to create and develop relationships. When there are people with whom you want to get along, you may be less assertive as you put their needs above your own. If getting along is your top priority and people ask where you would like to go for lunch, you might respond, “Where would you like to go?” They may want to get along too and say, “Wherever you like. Are you hungry?” To which you might respond, “Are you hungry?” In this situation, personal desires are of lesser importance than the intent to get along with other people.

Sometimes, however, standing out from the crowd becomes a higher people priority.

Get Appreciation from People

The fourth general intent, get appreciation from people, requires a higher level of assertiveness and a people focus, in order to be seen, heard, and recognized. The desire to contribute to others and be appreciated for it is one of the most powerful motivational forces known. Studies show that people who love their jobs, as well as husbands and wives who are happily married, feel appreciated for what they do and who they are. If getting appreciation is your intent when you go to lunch with friends, you might say, “There’s this fantastic restaurant I want to take you to! You’re going to love it. People thank me all the time for bringing them to this place.”

Sometimes You Get What You Give. It is important to find a balance between these two intents. We believe that you get appreciation by giving it. Giving appreciation and getting along with others go hand-in-hand. But any number of variables can shift this balance. For example, if you were the new employee in the office, initially you might lean more toward getting along, taking care to be considerate, concerned, and helpful. As the time approached for promotions, the balance could shift dramatically toward getting appreciation! If you were afraid your efforts would be overlooked, you might care less about the feelings of others than before. Similarly, in the courtship that precedes marriage, people tend to show great concern for each other’s needs and interests. Years later, it is not uncommon to hear marriage partners demanding that their own needs be met.

It’s a Question of Balance

All of these intents, getting it done, getting it right, getting along, and getting appreciation, have their time and place in our lives. Often, keeping them in balance leads to less stress and more success. To get it done, take care to get it done right. If you want it done right, avoid complications by making sure everyone is getting along. For a team effort to succeed, each party must feel valued and appreciated. Though the priority of these intents can shift from moment to moment, the shaded inner circle represents the normal balance of these intents in us all. We call it the Cooperation Zone. When people are in the Cooperation Zone, though their intents may differ, they are not in conflict or threatened by each other.

As Intent Changes, So Does Behavior

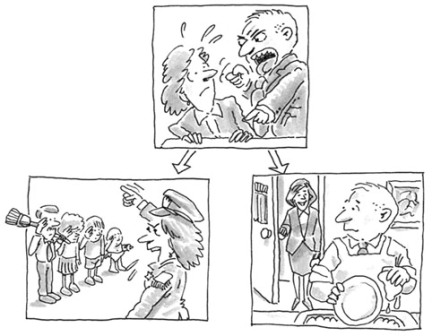

Consider the following situations to observe how behavior changes with intent.

Jack has been given a project to do at work. He has three weeks to do it, and since it could lead to a promotion, he really wants to make sure it is done right. He needs some figures from his coworker Ralph. Ralph hands him the paper and says, “The bottom line came to about 1050.” Jack says, “What do you mean ‘about 1050.’ What specifically is it?” Ralph says, “1050.” Jack says, “Are you sure?” Ralph replies, “Yeah, pretty sure.” Jack calls his wife and tells her he will be coming home late. That night he locks himself in his office to slowly and methodically check Ralph’s figures. Where do you think he is in the lens?

Obviously his priority is to get it right. He slows down and withdraws into the task to make sure it is done correctly.

It is the weekend now, and Jack is working away in his home office. His seven-year-old daughter comes in and says, “Daddy, Daddy, come look at the painting I did in my room.” Jack pushes his work aside and spends the rest of the afternoon playing with his daughter. That night his wife says she got a sitter, and she suggests that they go out for a nice dinner alone. When she asks where he would like to go, he replies, “Wherever you want.” At dinner she asks if he will have time tomorrow to fix that leaky faucet in the kitchen. Jack thinks of his project and knows he doesn’t really have time but says, “Okay. Sure thing.” Where is he now?

Obviously, to get along is Jack’s intent. He puts his needs aside to please the people he cares about. The project suddenly becomes secondary to getting along with family.

The next day Jack fixes the plumbing, and while he is in a fix-it mode, he repairs the burner on the stove that wasn’t working and replaces a torn screen. When his wife comes back from shopping, she wants to show him what she bought, but he first insists on showing her what he did. Where is Jack now?

If you said “getting appreciated,” very good. Take note that when his wife comes home, if he were in a getting along mode, he probably would first look at what she had bought. Since getting appreciated is primary, he can’t wait to show her what he did.

Jack doesn’t get as much done over the weekend as he had hoped, and the next week gets eaten up in crisis. Suddenly the deadline is upon him. He is working at home when his youngest daughter comes to him and asks if he will sit in her room while she goes to sleep and protect her from monsters. He says, “There are no monsters in your room. Now go to bed.” A little later his wife asks if he wants to have some tea with her. Without looking up, he just flatly says, “No.” Then she inquires about what they might do this upcoming weekend and offers some options. “Look, I don’t have time for this right now!” he testily responds. “Just pick one.” He turns back to his work. “Darn!” he thinks. “I am going to have to guess at some of these figures.”

Now where is Jack?

“Get it done” is the answer. Under the pressure of a deadline, Jack becomes more task focused and is not willing to take time for family. His communications are more direct and to the point. He is now willing to guess at some of the figures. That would have been unthinkable a few weeks earlier, when he had the luxury of time to get it right.

Notice in these examples how Jack’s behavior changes according to what is most important to him in a particular situation and time. The point here is that behavior changes according to intent, based on the top priority in any moment of time. We all have the ability to operate out of all four intents. To communicate effectively with other people, you must have some understanding of what matters most to them.

You Can Hear Where People Are Coming From

So how can you identify the intent of other people? One rapid indicator is their communication style. Let’s go to a meeting where four people with different primary intents each have something to say. Your mission is to attend to each one’s communication style and determine that person’s primary intent.

The first person says, “Just do it! What’s next on the agenda?”

Which intent would most likely be represented by such a brief and to-the-point communication style? If it sounds to you like “getting it done” is the priority here, then you’re ready to move on to the next example. When people want to get it done, they keep their communications short and to the point.

The next person at the meeting says, “Uh ... given the figures from the past two years, and taking into account inflation, fractionation of markets, foreign competition, and of course extrapolating that into the future ... I ... uh ... think it would be to our benefit to take more time to explore the problem fully, but if a decision is required now, then ... do it.”

Which intent would most likely be represented by such an indirect and detailed communication style? If you’re thinking “get it right,” you just got it right. Notice that both people said “Do it.” But the get it right person would never think to say that without backing it up with details.

Now a third person at the meeting speaks up: “I feel ... and tell me if you disagree because I really value your opinions—in fact I have learned so much working with you all—but I was just thinking ... if everybody agrees, then maybe we really should do it? Is that what everyone wants to do?”

Which intent would most likely be represented by such an indirect and considerate communication style? If you feel comfortable with this as an example of “getting along with people,” then you’ll fit right in.A person in the get along mode will be considerate of the opinions and feelings of others.

Suddenly, the fourth person at the meeting stands up (though everyone else has been sitting) and loudly proclaims, “I think we should do it, and I’ll tell you why. My granddaddy used to tell me ‘Son ... if ya snooze, ya lose.’ I never knew what he meant, but I never let that stop me. Y’know, that reminds me of a joke I heard. You’re going to love this one ...”

While that person keeps on going, we’d like you to stop and consider which intent would most likely be represented by such an elaborate communication style. If you’re thinking “get appreciation from people,” you’ve done a fine job so far of learning to recognize intent from a person’s style of communication. The person in the get appreciated mode is more likely to be flamboyant.

Can you understand how people with different primary intents can drive each other crazy?

Now think of the problem people in your life. In the situations in which you find them difficult, can you recall how they communicate? How about your communication? Who was more direct and to the point? Who was more detailed? Who deferred to others? Who was more elaborate? Who focused more on the task, and who focused more on the people? Who was aggressive, and who was passive? By observing behavior and listening to communication patterns with your problem people, you can recognize primary intent.

Shared Priorities, No Problem

When people have the same priorities, a misunderstanding or conflict is highly unlikely. For example:

The person you are working with on a project wants to get it done. You’re focused on the task, you’re getting it done, and your communications with them are brief and to the point.

The person you are working with wants to get it right. You’re focused on the task, you’re paying great attention to the details, and your reports to them are well documented.

The person you know wants to get along with you. With your friendly chitchat and considerate communications, you let him know that you care about him and like him.

The person you know wants to get appreciation for what they’re doing. With your enthusiasm and gratitude, you let her know that you recognize her contributions.

What Happens When the Intent Isn’t Fulfilled?

When people’s intents are not met, their behavior begins to change. When people want to get it done and fear it is not getting done, their behavior naturally becomes more controlling, as they try to take over and push ahead. When people want to get it right and fear it will be done wrong, their behavior becomes more perfectionistic, finding every flaw and potential error. When people want to get along and they fear they will be left out, their behavior becomes more approval seeking, sacrificing their personal needs to please others. When people want to get appreciation and fear they are not, their behavior becomes more attention getting, forcing others to notice them. And so it begins. These four changes are only the beginning of a metamorphosis into people you can’t stand. Using our lens, these changes are represented by the area just outside the Cooperation Zone called the Caution Zone.

If you notice these changes in behavior, then you should immediately focus on blending (Chapter 4) with those people. But what if they aren’t willing to be flexible? Well, do you want to see something really scary? Their behavior will continue to change until they become your worst problem-people nightmare.