The Know-It-All

Young Dr. Bosewell was an intern with an avid interest in clinical nutrition. He pursued this interest in his spare time, of which there was precious little. Such was his dedication to healthcare that it was the rare week that went by when you couldn’t find Dr. Bosewell in the medical school library for a least a few hours, searching literature and reading books and articles. Unfortunately, his clinical supervisor was an elderly physician, Dr. Leavitt, who had made up his mind long ago on these matters. He considered nutrition to be little more than the basic food groups and nutritional therapy to be a form of quackery. In the mind of Dr. Leavitt, real medicine came in only two forms, drugs and surgery.

Time and again, during clinic conferences, Dr. Bosewell would try to suggest nutritional therapies. He was fully prepared to present the research to substantiate his suggestions because he believed this was for the betterment of the patients. But Dr. Leavitt, drawing on years of experience and accumulated wisdom, would always cut off the young intern with a commanding voice, and then he would condescend to set the record straight in short order:

“Bosewell! Have you been hanging out in health food stores again? How many times do I have to tell you this? Let’s hear no more of this so-called therapeutic nutritional nonsense! As I’ve said, the treatment is straightforward. Next case.”

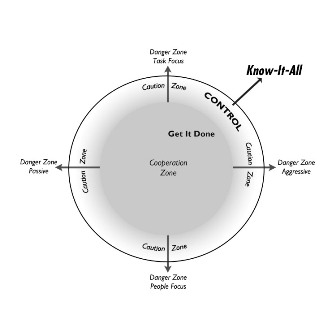

Know-It-Alls like Dr. Leavitt are knowledgeable and extremely competent people, highly assertive and outspoken in their viewpoints. Their intent is to get it done in the way that they have predetermined is best. They therefore can be very controlling, with a low tolerance for correction and contradiction. New ideas or alternative approaches are frequently perceived as challenges to the Know-It-Alls’ authority and knowledge, regardless of the merits of the ideas or approaches. When their decisions and opinions are challenged, they rise to the occasion. And when their decisions and opinions are questioned, they question the questioner’s motives.

Know-It-Alls believe that to be wrong is to be humiliated. They feel it is their destiny and their duty to dominate, manipulate, and control. They have no qualms about taking your time to talk, but they will waste no time with the inferior ideas of others. As a result, it is quite difficult and next to impossible to get your two cents in.

You’d Better Adjust Your Attitude

When confronted by Know-It-Alls, you must overcome the temptation of becoming a Know-It-All yourself. Becoming like them could lead to mental rigidity as well as the musculoskeletal problems that accompany the refusal to bend your neck and yield once in a while.

You also must overcome the temptation to resent Know-It-Alls for their arrogant refusal to get a second opinion. These resentments have a tendency to build up until they blow up into an argument, which is pointless and which you will more than likely lose.

Instead of helping Know-It-Alls to make you miserable, you can retrain yourself to be flexible, patient, and very clever about how you present your ideas. So, it’s your decision. Is it worth it to you to do what it takes to deal effectively with these people you can’t stand? If the answer is yes, then reframe your experience by seeing through the eminence front of Know-It-Alls. Realize that these closed-minded difficult people have doomed themselves to struggle with one of the primal forces of life: uncertainty. The most that can be won in this struggle is the booby prize of being right. For, as Marcel Proust once said, “The real voyage of discovery is not in seeking new lands but in seeing with new eyes!” In such a narrow world of their own creation, Know-It-Alls are, no doubt, very unhappy and insecure people inside, no matter how clean the lab jacket or impeccable the résumé.

Next, go into your experimental laboratory, and remember previous experiences with Know-It-Alls. Ask yourself what you could have done differently. Who among the people you know have the resources of patience, flexibility, and cleverness? How would they have handled that situation? When and where in your own life have you had those qualities? Go back, in your mind’s eye, to prior encounters with your Know-It-Alls. Replay the incidents several times in a resourceful manner to develop patience and precision. You’ll need these resources when you present your ideas and alternative approaches to the Know-It-Alls in a nonthreatening manner.

Your Goal: Open the Know-It-All’s Mind to New Ideas

Your goal with Know-It-Alls is to open their minds to new information and ideas. A day may come when you have a better idea or the missing piece of the puzzle! When that day comes, and you feel the moral imperative of getting your idea implemented, take aim at the goal and go for it. If Know-It-Alls stand in your way, let your mounting frustration become sheer determination to open their mind to your idea.

Action Plan

Step 1. Be Prepared and Know Your Stuff. The Know-It-All’s defense system monitors incoming information for errors. If there are any flaws in your thinking or if your idea is unclear on any point, the Know-It-All’s radar will pick up the shortcoming and use it to discredit your whole idea. Therefore, in order to get the Know-It-All to consider your alternatives and ideas, you must clearly think through your information ahead of time. Since a Know-It-All has little patience for the ideas of others, you will have to know what you want to say and how to say it briefly, clearly, and concisely.

Step 2. Backtrack Respectfully. Be warned: you will have to do more backtracking with Know-It-Alls than with any other difficult Danger Zone behaviors. They must feel like you have heard and understood the “brilliance” of their point of view before you ever redirect them to your idea. If Know-It-Alls say something and you don’t say it back, you run the risk of having to listen to them as they repeat themselves, over and over again, if necessary, until you submit. Obviously, this could be a very frustrating, lengthy, and unpleasant experience. Some call it torture. Whatever you call it, it’s better off avoided.

Backtracking is a sure signal to your Know-It-All that you’ve been listening. However, it’s not enough to simply backtrack. Your whole demeanor must be one of respect and sincerity. There cannot be so much as a hint of contradiction, correction, or condescension, or a trace of disagreement. You want to look and sound like you understand that the Know-It-All’s point of view is, in fact, the correct one. Patient backtracking can help you to give that impression. If you backtrack too quickly, it can sound insincere, as if you are doing it to lead up to your own point of view. Though Know-It-Alls like to get it done, they are usually willing to stop and appreciate their own brilliance when it’s reflected back to them.

However, if your Know-It-All seems to be getting impatient with you, then backtrack a little less and move forward. If you hear, “Just get to the point!” complete backtracking and move on to Step 3.

Step 3. Blend with Their Doubts and Desires. If the Know-It-All really believes in an idea, it is because of specific criteria that make that idea important. If the Know-It-All has doubts about your idea, then those specific criteria, the reasons why or why not, aren’t being addressed. You will find it helpful to blend with those criteria, by acknowledging those criteria/reasons before you present your idea. Then show how your idea takes those factors into account.

How can you know the Know-It-All’s highly valued criteria? Well, as luck would have it, Know-It-Alls also have a tendency to develop a finite set of dismissal statements that reflect those highly valued criteria. Through time, these statements become extremely predictable to an attentive listener. Regardless of the idea under discussion, your Know-It-All, at some well-chosen point of discussion, may interject a standard dismissal like, “We don’t have time” or “We can’t afford to make changes at this point.” If you suspect that one of these dismissals will be used to undermine the validity of your information, state it before the Know-It-All has a chance to say it to you.

In general you can dovetail your idea with the doubts of Know-It-Alls, by paraphrasing the dismissal statements as a preface to your idea. You can also dovetail with the desires of Know-It-Alls, by showing how your idea meets their criteria:

“Since we can’t afford to make unnecessary changes ...”

OR

“Since we have no time for ...”

By backtracking with respect so that they feel like you really understand what they said and by blending with their doubts and desires, you create a gap in their defense system through which you can get their attention and present your information. Since none of your behavior could be construed as an attack, there is nothing for them to defend. You are now at the moment of truth.

Step 4. Present Your Views Indirectly. Proceed quickly but cautiously at this step. You have temporarily disengaged their defense system. The time has come to redirect them to your idea or information. While you redirect, prevent the Know-It-All from raising shields again by remembering these helpful hints:

• Use softening words like maybe, perhaps, this may be a detour, bear with me a moment, I was just wondering, and what do you suppose to sound hypothetical and indirect, rather than determined and challenging.

• Use plural pronouns like we or us, rather than singular pronouns like I or you: “What do you suppose might happen if we ...” or “What might result if we were to ...” Again, this serves as a subtle reminder that you are not the enemy and they are not under attack. It also gives the Know-It-All a bit of ownership over the idea as he or she considers it.

• Use questions instead of statements. When people act like Know-It-Alls, they feel they must know the answers to questions. That means they must consider the question in order to answer it. For example: “Bear with me, but I was wondering, what do you suppose would happen if we were to try [your information and ideas] out in these specific ways?”

• As you ask your question, include how all the Know-It-All’s doubts and desires will be handled if he or she acts on your ideas and information.

All of these steps for dealing with Know-It-Alls require extreme patience on your part. You have to think before you speak, you have to backtrack with sincerity, you have to dovetail everything you say with their doubts and desires, and you have to be indirect about new ideas. (And you may have to take your antinausea pills before you do any of it.)

As is true with all difficult people, you must first decide whether or not the end result is worth what it will take to get there. But the good news is that this strategy gets easier to implement as time goes on. It’s not that your back gets more flexible. It’s just that as you continue to approach Know-It-Alls in this nonthreatening way, you begin to appear on their screen as “friendly.” As your ideas get through and those ideas prove to be effective, you develop a track record that gains you respect in their eyes.

Step 5. Establish a Mentoring Relationship. Here is a shortcut to the long-range change that you desire: you can openly acknowledge these knowledgeable problem people as your mentors, in some area of your life that you seek to develop.

Penny, a friend of ours from Ohio, had a stellar track record and résumé. She went to work in a large banking system while quite young, and her goal was to become the youngest executive in the history of that institution. Not surprisingly, Penny had great success in her quest, and in very little time she achieved an executive position. That’s when her problems began. She found her every idea, suggestion, and product proposal opposed by a fellow named Dennis, whom she nicknamed “The Menace!” Dennis had been a part of the system, it seems, since its origin. He had been a personal friend of the bank’s founder, and his brain contained the collected knowledge and wisdom of every giant that had ever walked the bank’s hallowed halls. No sooner would Penny speak up then Dennis would counter, “They tried that 15 years ago, and it was a miserable, expensive failure. No point wasting resources on a failed idea!”

Undaunted—a word that aptly describes Penny’s approach to problems—she began looking for her opportunity to change the relationship dynamic. And the opportunity did present itself, in the form of a proposal offered by Dennis at a meeting. Using an astounding number of handouts, charts, tables, and graphs, Dennis proposed a product that could help the bank profitably weather uncertain times in a struggling industry. And the proposal really was brilliant.

At the end of the meeting, Penny approached Dennis in the hallway, and she asked him for a personal copy of the proposal, telling him that she admired his work and wanted to study the proposal further. Like a farmer gathering in the harvest, Penny sat down with the proposal and a legal pad, and for several days she gleaned as much knowledge, wisdom, and experience from it as she could. Using the proposal as a spring board, she dug deep, tracing ideas back through the history of the bank, examining reference documents, and conducting other research. When she was done, she copied her notes, clipped them to the top of the proposal, and handed the whole stack of it to Dennis in person.

“Incredible,” Penny told him. “Remarkable, inspiring, thorough, impeccable,” she went on. “I do believe I’ve learned more from your work on this proposal than any other experience I’ve had in my time with this bank. Thank you.” Penny says that from that day on, the relationship was transformed. When it comes to Dennis, whatever Penny wants, Penny gets.

By letting Know-It-Alls know that you recognize them as experts and that you are willing to learn from them, you become less of a threat. This way, Know-It-Alls spend more time instructing you than obstructing you. It is entirely possible that you will find your way from the “disenfranchised” group into the “generally recognized as safe-to-listen-to” group. Consequently, more of your ideas and information will get heard with much less effort on your part and less resistance on theirs. As your good ideas pan out, you will impress the Know-It-Alls with your wisdom and gain their respect.

Great Moments in Difficult People History

The Case of Young Dr. Bosewell and the Chronic Know-It-All Syndrome

“Laboratory tests indicate that the white blood cell count is elevated, and we are seeing the usual anemia. Liver function tests are abnormal including serum bilirubin, SGOT, SGPT, and serum alkaline phosphate. In theory the treatment is straightforward, though often difficult. Stop drinking. A nutritious diet and perhaps some corticosteroids to control the hepatitis. Any questions?”

Young Dr. Bosewell raises his hand. As Dr. Leavitt peers over his glasses and nods, Bosewell rises to his feet, clears his throat, and begins to speak:

“Dr. Leavitt, sir. If I understand you correctly, the peripheral neuropathy, glossitis, and tender hepatomegaly are all characteristic signs of the start of alcoholic cirrhosis?” [Backtrack with respect]

“Yes,” Dr. Leavitt mumbles and affirms with a nod.

“And laboratory tests indicate that the white blood cell count is elevated, liver function tests are abnormal, and we are seeing the usual anemia?” [Backtrack with respect]

“Yes.”

“And sir, the nutritious diet you’re referring to, I believe the Merck manual recommends 70 grams of protein a day as tolerated by the patient. Is that right, sir?” [Know your stuff]

Dr. Leavitt raises his eyebrows slightly, and with a quick glance around the room at the other students, he says, “Very good, Bosewell. You’ve done your homework.”

Dr. Bosewell clears his throat again and continues, “Thank you, sir. This may be a bit of a detour, sir, but I was reading in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition about some research on the amino acid L-carnitine and its effect on liver function. Now I know your feeling about ‘health supplements.’ [Blend with doubts] You don’t want our patients getting improper treatments. And I certainly remember the story you told us about the patient you saw as an intern, the one who died from treating himself because he didn’t want to believe his doctors, and it has always haunted you that maybe you could have done something more.” [Blend with doubts]

“But, sir, I am thinking about patient compliance. [Blend with desires] No treatment does any good if the patient doesn’t comply. This is a patient who has asked us for information on nutrition. And, well, according to the article in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, L-carnitine 500 milligrams twice a day may improve liver function. If nothing else, it might improve our rapport with the patient and patient compliance with our treatment. [Blend with desires] I was just wondering what you’d think about our prescribing that for this patient?” [Note: By ending with a question, Dr. Bosewell gives Dr. Leavitt control.]

Dr. Leavitt considers what he’s heard for a moment. Abruptly, the old man speaks: “Very well. I suppose it could do no harm and may even help. Go ahead. You’re in charge of it, Bosewell. Keep close tabs, and report back to us. Who has the next case?”

By backtracking Dr. Leavitt’s comments, Dr. Bosewell demonstrated his respect, interest, and attentiveness. He presented his idea as a detour. He dovetailed his idea with Dr. Leavitt’s doubts about health supplements in order to prevent a possible objection. He blended his idea with Dr. Leavitt’s desires by linking patient compliance to proper treatment. And he redirected in the form of a hypothetical question using the pronoun our so that there was no hint of a challenge to Dr. Leavitt’s authority.

The long-range change is worthy of comment as well. You see, Know-It-Alls are capable of respecting knowledge in others if you can get them to notice it. As Dr. Bosewell’s nutritional therapies panned out, Dr. Leavitt began to respect Dr. Bosewell. By the time young Dr. Bosewell finished his internship at the hospital, Dr. Leavitt was turning to him spontaneously in clinic conference and asking, “Young Dr. Bosewell! Tell the class what the nutritional world holds for this type of patient.” Dr. Bosewell told us that Dr. Leavitt’s attitude didn’t change with anyone else. But rumor has it that Dr. Leavitt was overheard in the faculty lounge bragging, “That young budding Know-It-All reminds me of myself in my med school days!”

The Carpenter’s Story

When we were student doctors, we saw a patient named Max whose chief complaint was a stomach ulcer. We couldn’t help but inquire in depth as to what was eating him. We also couldn’t help noticing the way he carried himself. His every movement was perfectly coordinated with great care. He appeared at all times to be in complete control of himself. We learned that he was a dedicated martial artist and that he had developed himself through this discipline from a very young age.

As his story unfolded, we learned that he earned his livelihood as a carpenter. He worked in a carpentry shop belonging to an elderly Japanese gentleman, Mochizuki, who had trained him in the higher levels of his martial arts discipline. Max had taken the job to honor the request of his teacher. Mochizuki’s son, Ishida, also worked in that shop. When Mochizuki wasn’t around, Ishida would stand over Max and criticize his work. Sometimes his comments were valid, other times they weren’t, but more often than not it was really just a matter of preference. Max was deeply annoyed by this, but Max said and did nothing about it. He didn’t want to offend his teacher by complaining about his son.

Instead, Max used the self-discipline he had learned from martial arts to suppress his thoughts and feelings (particularly the thoughts about using Ishida as a practice dummy). As we talked, Max reframed his ulcer as an unconscious mechanism that was forcing him to deal with the discomfort of his work situation. We asked Max if there were some other ways that he could handle the situation, besides suppressing his thoughts and feelings. Max said he could leave, but he didn’t want to do that because he learned so much when Mochizuki was around. Another idea was to continue as he had in the past. His stomach actually hurt when he thought about that one. His third option took us all by surprise. Max suddenly saw himself letting Ishida be the expert. He imagined himself thrusting the tools toward Ishida and saying, “Show me.” He kind of smiled at that one.

And that, in fact, is what Max ended up doing. Whenever Ishida approached, Max would circumvent the once-inevitable criticism by voluntarily turning it into a learning opportunity. “I want to learn. Show me what you would do.” [Turn them into mentors] Ishida had not anticipated this development and was initially taken aback. In time, he was moved by this gesture, and he became less harsh with Max. Though they never became friends, the relationship did become friendlier. Max actually learned some valuable techniques, and Ishida acknowledged the artistry of Max’s work. Best of all, Max’s ulcer symptoms went away completely.

Quick Summary

When Someone Becomes a Know-It-All

Your Goal: Open the Person’s Mind to New Ideas

ACTION PLAN

1. Be prepared and know your stuff.

2. Backtrack respectfully.

3. Blend with their doubts and desires.

4. Present your views indirectly.

5. Establish a mentoring relationship.