Introduction

IS DEMOCRACY IN RETREAT?

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948, spells out a list of rights deemed to be non-negotiable: Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person. Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; to freedom of peaceful assembly and association; and to take part in their government, directly or through freely chosen representatives. The declaration does not use the term “democracy,” but that is exactly what it describes.

Even leaders who are undeniably authoritarian make some claim to the mantle of democracy, either by holding sham elections or by trying to broaden the definition of “rights” to encompass goods they can deliver, like prosperity. Those who are not subject to popular will still crave legitimacy—or at least the appearance of legitimacy. Saddam Hussein held elections in Iraq in October 2002, just a few months before he was overthrown. (He was the only choice on the ballot and won 100 percent of the vote, with the official turnout also at 100 percent.) Few will say they simply rule by fiat, something that would have been wholly acceptable in times past. France’s Sun King, Louis XIV, who declared, “I am the State,” is one of many monarchs from history who claimed to rule by divine right.

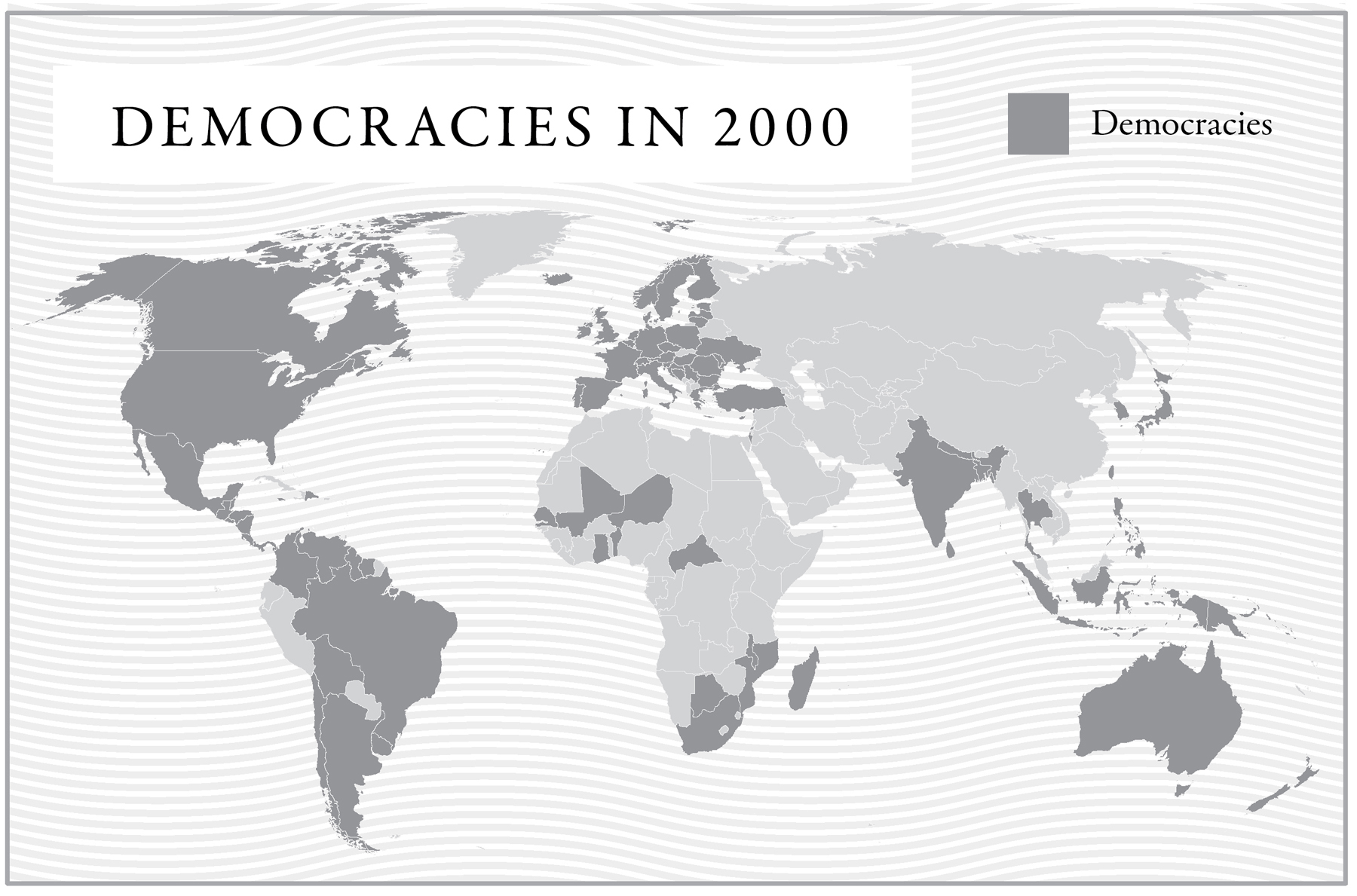

If democracy is broadly understood to mean the right to speak your mind, to be free from the arbitrary power of the state, and to insist that those who would govern you must ask for your consent, then democracy—the only form of government that guarantees these freedoms—has never been more widely accepted as right.

Yet, while the voices supporting the idea of democracy have become louder, there is more skepticism today about the actual practice and feasibility of the enterprise. Scholarly and popular discourse is filled with declarations that democracy is in retreat or, at least, as Larry Diamond, my colleague at Stanford, has said, in “recession.”1

The pessimism is understandable, particularly given events in the Middle East, where the promise of the “Arab Spring” seems to lie in tatters. If there is cause for optimism, it is in recognizing that people still want to govern themselves. Democracy activists in Hong Kong and mainland China risk persecution and arrest if they press their cause. Elections still attract long lines of first-time voters, even among the poorest and least-educated populations in Africa—and sometimes even under threat from terrorists in places like Afghanistan and Iraq. No matter their station in life, people are drawn to the idea that they should determine their own fate. Ironically, while those of us who live in liberty express skepticism about democracy’s promise, people who do not yet enjoy its benefits seem determined to win it.

Freedom has not lost its appeal. But the task of establishing and sustaining the democratic institutions that will protect it is arduous and long. Progress is rarely a one-way road. Ending authoritarian rule can happen quickly; establishing democratic institutions cannot.

And there are plenty of malignant forces—some from the old order and some unleashed by an end to repression—ready to attack democratic institutions and destroy them in their infancy. Every new democracy has near-death experiences, crucible moments when the institutional framework is tested and strengthened or weakened by its response. Even the world’s most successful democracies, including our own, can point to these moments, from the Civil War to the civil rights movement. No transition to democracy is immediately successful, or an immediate failure.

Democracy’s Scaffolding

Democracy requires balance in many spheres: between executive, legislative, and judicial authority; between centralized government and regional responsibility; between civilian and military leaders; between individual and group rights; and ultimately between state and society. In functioning democracies, institutions are invested with protecting that equilibrium. Citizens must trust them as arbiters in disputes and, when necessary, as vehicles for change.

The importance of institutions in political and economic development has long been noted by social scientists in the field.2 In 1990, the American political economist Douglass North provided a succinct definition of institutions. He called them the rules of the game in a society—or, in other words, “humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction.”3

At the beginning, formal protections—such as constitutionally determined organizations, laws, procedures, or rules—may reflect bargains between various interests in the society. As such, they may be imperfect and sometimes contradictory. This will breed contention for years to come. Every democracy is flawed at its inception. And, indeed, no democracy ever becomes perfect. The question is not one of perfection but how an imperfect system can survive, move forward, and grow stronger.

Moreover, these “humanly devised constraints” are, at the beginning, just words on paper. The puzzle is how they come to actually “shape human interaction.” In other words, how do institutions become legitimate in the eyes of the citizen—legitimate enough to become the vehicle through which people seek protection and change?

We know the goal: Social and political disruption takes place within the institutions. While some fringe elements may operate outside of them, the great majority of people trust them to live up to their stated purpose. The paradox of democracy is that its stability is born of its openness to upheaval through elections, legislation, and social action. Disruption is built into the fabric of democracy.

The Myth of “Democratic Culture”

No nationality or ethnic group lacks the DNA to come to terms with this paradox. Over the years, many people have tried to invoke “cultural explanations” to assert that some societies lack what it takes to establish or sustain democracy. But this is a myth that has fallen to the reality of democracy’s universal appeal.

It was once thought that Latin Americans were more suited for caudillos than presidents; that Africans were just too tribal; that Confucian values conflicted with the tenets of self-rule. Years before that, Germans were thought too martial or subservient, and—of course—the descendants of slaves were too “childlike” to care about the right to vote.

Those racist views are refuted by stable democracies in places as diverse as Chile, Ghana, South Korea, and across Europe. And, of course, America has now had a black president, as well as two secretaries of state and two attorneys general. Even if these “cultural” prejudices have simply not held up over time, the question hangs in the air: Why have some peoples been able to find the equilibrium between disruption and stability that is characteristic of a democracy? Is it a matter of historical circumstances? Or is it simply a matter of time?

Scholars have offered a number of answers to these questions. Perhaps the most prevalent is that the poorer the country and the lower the levels of education, the less likely the chances for the establishment of a stable democracy.

Others have emphasized the type of interaction between non-democratic regimes and their oppositions. If the end of the old order does not come through violence but rather through negotiation, the chances for success increase.

Finally, the state of the society itself is clearly a factor. A more ethnically homogeneous population is likely to find it easier to achieve stability. And if civil society—all the private, non-governmental groups, associations, and institutions in the country—is already well developed, the scaffolding for the new democracy is stronger.

Unfortunately, these idyllic conditions rarely exist in the real world. When people want to change their circumstances they are unlikely to wait until they have achieved an appropriate level of GDP. Sometimes the old regime has to be overthrown violently. Ethnically homogeneous populations are rare. More often, the history of revolution begins with oppression of one group by another. It is difficult for civil society to develop under repressive regimes. Checks and balances are most robust when they come from multiple sources—from outside governing bodies as well as within them. Authoritarians fully understand and depend on the absence of a well-developed institutional layer between the population as a whole and themselves. They trust that the mob will likely have incoherent views of its interests. The masses might even be easy to manipulate, producing fertile ground for the kind of populism associated with the Peronists in Argentina or the National Socialists in Germany.

But if the mob organizes independently and pursues its collective interest through new groups and associations, it can become an effective counterweight and a force for change. That is why from Moscow to Caracas, civil society is always in the crosshairs of repressive regimes.

In short, democracy, particularly in its first moments, will be messy, imperfect, mistake-prone, and fragile. The question isn’t one of how to create perfect circumstances but how to move forward under difficult conditions.

It Depends on Where You Start

Democratic institutions are not born in a historical vacuum. A landscape is already in place when the opportunity for change—the democratic opening—comes. As important as larger factors like GDP and literacy may be, transitions to democracy are really stories about institutions and how quickly they can come to condition human behavior.

Below we identify four institutional landscapes. These categories are analytically discrete, but in reality there is likely some overlap. Yet grouping them in this way illuminates the institutional possibilities at the time of a democratic opening: The lay of the land matters. Leaders’ choices matter too, but they are constrained by the institutional landscape within which they are expressed.

Type 1: Totalitarian Collapse: Institutional Vacuum

Totalitarians leave no aspect of life untouched—the space from science to sports to the arts is occupied by the regime. Benito Mussolini coined the term totalitario, describing it to mean “All within the state, none outside the state, none against the state.” Existing institutions (the Ba’ath Party of Saddam, the National Socialists of Germany, Stalin’s Communist Party) are little more than tools of the regime. In Nazi Germany, science was placed at the service of the “Aryan ideal,” promoting eugenics and theories of racial superiority. The Soviet Union persecuted some of its finest artists, composers like Shostakovich and Prokofiev, for writing music that was not socialist enough. Saddam Hussein’s henchmen brutalized members of the national soccer team for performances that did not glorify the regime.

Every aspect of life is penetrated in some way. The regimes are often “cults of personality”—the entire society bent to the whims of a single leader. North Korea is the most prominent example today.

When a regime of this kind is decapitated—often with the assistance of an external power—there is an institutional void and thus little that can channel the unleashed passions and prejudices of the population. These are revolutions. New institutions have to be built, and built quickly. And they have weak, if any, indigenous roots to support them. There is a wide gulf between the long time needed to build new institutions and the limited raw material to do so.

Because the experiences of Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya are so recent and cataclysmic, these cases of totalitarian collapse have come to shadow discussions of the challenges facing democratic transitions. But these examples are the exception not the rule. Most are less chaotic and violent—though still exceedingly difficult.

Type 2: Gradual Decay of Totalitarian Regimes: Institutional Antecedents Remain

Communism died slowly. Soviet officials and the population alike referred to zastoi, or “stagnation.” We know now that it was really decay. Repeated crises, usually because the governments could not deliver economic benefits, produced cycles of reform and repression. Each time, though, the distance between the party and the people grew.

Throughout the region, this situation elicited varying responses. Romania staked its claim as a maverick within the Soviet bloc, playing a nationalist card and publicly insisting on independence from Moscow. Reformists within the Hungarian Communist Party turned away from repression and launched privatizing economic reforms. The trauma of 1968 caused the Czechoslovak Communist Party to toe the Soviet line. But within the country, survivors of that period created Charter 77—a movement of intellectuals devoted to human rights and freedom. Poland, as we will see, experienced multiple episodes of reform and repression. Only East Germany seemed solidly and irrevocably hard-line and uncompromising.

Gorbachev’s arrival as general secretary of the Soviet Communist Party in 1985 boosted these liberalizing trends in East-Central Europe. The new Soviet leader made it very clear that change was needed. He encouraged reformers in Hungary and Poland and criticized laggards like Erich Honecker in East Germany. At first reform came mostly from within the communist parties but—owing to the growing sense of public openness—civil society and independent political forces also seized the opportunity before them.

In the Soviet Union itself, perestroika and glasnost gave life to opposition groups and created new institutional arrangements—particularly in Moscow and Leningrad. Similar developments also arose outside of Russia: in Ukraine, Georgia, and the Baltic states. Communist institutions remained, including youth organizations like the Komsomol. It was still the case until the end of the Soviet Union in 1991 that rectors of major universities could not serve without the party’s approval. Still, civil society groups began to organize around different issues, from the environment to disability rights. What began as societal, cultural, and economic space would soon become political.

Gorbachev did something else that changed the landscape: He delivered the population from the shadow of repression and fear. At every turn during this period, the Soviet Union failed to use sufficient force to change the course of events. And when it did use force, such as against anti-Soviet demonstrations in Tbilisi in April 1989 and in the Baltics in 1991, the regime eventually pulled up and backed down at crucial moments, in effect emboldening the opposition.

Meanwhile, another set of institutions emerged as Boris Yeltsin gained popularity—institutions of a separate Russian state within the Soviet Union. Like the other republics of the Soviet Union, Russia had long had a ceremonial presidency and a legislative council (called a soviet). But these paper organizations meant little until the reforms of the late 1980s. Up to that point, Russia and the Soviet Union had been virtually synonymous. Yet Yeltsin breathed life into these Russian institutions, noisily quitting the Soviet Communist Party in 1990 and then getting himself elected president of Russia in 1991. These unfolding events changed the landscape dramatically.

Years before, however, the Helsinki Accords of 1975, which gave the Soviets what they thought was a major political victory, in fact had created a safe haven for East-Central European and Soviet civil society, with reformers in the region joining European and American counterparts in seminars and annual conferences. There were three components to the accord—economic, security, and human rights. The Soviet Union wanted to emphasize the first two but—to the surprise of many—signed on to the human rights “basket” as well. Moscow erroneously believed that the West was legitimizing the post–World War II order, and Soviet power within it. But giving members of civil society a safe way to challenge their government turned out to be a Trojan horse.

These factors, stretching back for decades, explain in part why the institutional landscape was richer when the democratic opening of 1989–91 arrived. First came the sudden and nonviolent collapse of Soviet power in Eastern Europe, exemplified by the collapse of the Berlin Wall. Then came the end of the Soviet Union itself, with newly independent states carved out of its carcass. The events were in some sense rapid, unexpected, and challenging. But the institutional raw material was, to varying degrees, reasonably good.

Type 3: Authoritarian Regimes and the Struggle for Meaningful Political Space

Unlike totalitarians, authoritarian regimes leave space for groups that are independent of them. Non-governmental organizations, the business community, universities, and labor groups live in an uncomfortable cold peace with their rulers. They are often the lead element in pressing for change.

Up to a certain point, these organizations are useful to the regime. Well-regarded universities provide intellectual capital and their reputation is a source of national pride. Business elites are needed to provide jobs and economic growth. Civil society can be a canary in the coal mine—expressing views that leaders need to hear, a kind of barometer of public discontent. But there are limits to what the regime will tolerate. It is a matter of balance—act before independent groups are a threat but not so brutally as to provoke a backlash. Thus, while overt repression is always an option, it can be more effective to apply intermittent pressure, such as jailing key civil society figures and journalists, raiding their offices, or shutting down newspapers or blogs to reassert that consequential politics is off-limits.

And authoritarian regimes leave little doubt about who controls the actual political space. Political parties may exist, but they cannot function. Cuba is one of the few remaining single-party states. Most authoritarian regimes have some semblance of electoral competition. But it is largely a façade. In Putin’s Russia, there is little doubt that the regime will win. Parliaments dare not challenge the president. The courts would never convict a member of the ruler’s family or his political cronies. The military and the police stand by ready to make sure that no lines are crossed.

Type 4: Quasi-Democratic Regimes: Fragile and Vulnerable Institutions

Finally, some places have an open and active political sphere, but their institutions themselves are immature and often viewed as hollow and corrupt. In countries like Liberia, Tunisia, and Iraq, the long struggle for democracy has just begun. Democratic institutions can be strengthened over time, but if they are viewed as ineffective, a vicious cycle can emerge as they fall into disuse, lose more credibility, and, consequently, are ignored. It is tempting to think that a good leader is all that is needed to make them work. But it is more likely that some seminal event or crisis will provide the crucible moment when the institutions can prove themselves—or not.

The analytic problem is that while democratic institutions are present in the landscape—parties, parliaments, courts, civil society groups—it is hard to know how strong or weak they are until they are tested.

Unlike in authoritarian regimes, elections in quasi-democracies are relatively free and fair, and people can change their leaders. So we can say that these states pass at least one important democratic milestone. In reality, though, elections can expose fissures in society. The results are often contested—there are many “50-50 countries” where the margins will be razor thin. Successfully navigating the aftermath is another milestone. Do candidates and their supporters go to the streets? Do they do so peacefully? In the best of circumstances, there are institutions that can respond—a court or electoral commission that can break the tie and make its ruling stick.

But the electoral story is only one element. Quasi-democratic states are in the midst of establishing the balance of forces needed to sustain democratic governance. In these places, civil society and a free press are critical checks on the power of government as events unfold. An independent judiciary is a bulwark against corruption and abuse. And the state has to be able to protect its people—that means it must maintain a monopoly on the use of force. Militias and armed insurgents can be the cause of state failure. Quasi-democratic governments may have passed the electoral test but the scaffolding of democracy may still be weak. The clay is not yet set. And an executive with too much power, ruling by decree and circumventing other institutions, is a sure path to authoritarian relapse. Such has been the case recently in Turkey and Russia and increasingly in Hungary.

Finally, when a country achieves a stable balance of democratic institutions, we can say it is a consolidated democracy. Some have described consolidated democracies as countries in which democracy becomes “the only game in town.”4

What Can Outsiders Do to Help?

Now we come to another piece of the institutional landscape: the role of external actors. Let us stipulate that any democratic transition will be easier if indigenous forces are well organized and able to take power and lead effectively. The dictum that you cannot impose democracy from the outside is undeniably true. But it is rare that there is truly no indigenous appetite for change. Those advocating reform may be weak and scattered—this is unsurprising since authoritarians do everything possible to keep them that way. Yet they often find a way to make their voices heard, reminding us that given a choice, few would choose to be abused by their leaders. Today, when social media makes certain that what happens in the village won’t stay in the village, people measure their circumstances against those of the larger world. So they will appeal to outsiders to help them. Their plight is hard to ignore.

The forces that have fed democratization have multiplied since the end of World War II. Civil society groups are well organized across borders. The machinery of the international community that supports democratic principles is highly developed. Organizations like Amnesty International train a spotlight on authoritarian regimes and pressure major powers not to back them. NGOs such as Freedom House, the National Endowment for Democracy, and the European Endowment for Democracy promote liberty and defend human rights. International election monitors now establish uniform standards for the peaceful transfer of power and call out regimes that don’t respect them.

Countries that have recently gone through democratic transitions now offer their own expertise and experience to others. Both Poland and Hungary have established organizations, such as the Solidarity Fund PL and the International Center for Democratic Transitions, to support democratization in places like Burma. India, a remarkable consolidated democracy, was the first contributor to the United Nations Democracy Fund. Taiwan established a Foundation for Democracy fifteen years ago—the first such effort outside of Europe, North America, and Australia.

Moreover, foreign aid donors often insist on a say in matters ranging from corruption to human rights to electoral integrity. Sanctions against authoritarian regimes are powerful when they are dependent on external economic assistance. With every passing day, sovereignty is dying as a defense against oppression within one’s borders.

And it is not as if the only active external forces are those promoting democracy. Cuba has long attempted to export its revolutionary ideology in Latin America. Venezuela’s oil wealth in the early twenty-first century was used aggressively by the late Hugo Chávez to influence elections throughout the region. China’s role in Africa is not an overtly political one, but economic assistance delivered without conditions emboldens those leaders who resist reform. Saudi Arabia supports hard-line Islamic elements in many countries. Obviously, the long reach of Putin’s Russia into the politics of Ukraine and other parts of Europe is undeniable. In fact, the depth of Russia’s interference in the political affairs of other countries—even those of the United States—is unfolding in shocking and disturbing ways.

In short, the question isn’t “Will there be an international role in countries undergoing democratic change?” There will be. The issue is “What will that role be and who will play it?”

Among great powers, the United States has been the most committed to the proposition that sovereignty provides no immunity for repression. Though the principle has been applied unevenly, no American president to date has abandoned it. America’s global reach has given it an outsized role in the promotion of democracy.

Perhaps this is why the template used by advocates for change bears a strong resemblance to America’s own constitutional principles. The Founding Fathers were focused first and foremost on the question of balance—how to make the state strong enough to perform key tasks but not so strong as to threaten individual liberties. Madison, Hamilton, and others saw this balance as the key to democratic stability.

The Hard Road to Democracy

America has found a stable equilibrium, but the path to it was hard and often violent. The litigation and re-litigation of the meaning of the Constitution continues to this day. So this book begins with America’s story as a primer on the institutions of consolidated democracy and as a reminder of the long road to get there and stay there.

We then examine several recent cases of democratic transitions. All involve choices by leaders, their people, and the international community as well, choices that were constrained by the institutional landscape they inherited.

We follow the struggles of Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Colombia, and Kenya to find a stable democratic equilibrium. We see institutions under fire and how they fared. Colombia is a tale of finding the sweet spot between chaos and authoritarianism that we call democracy. The jury is still out on Ukraine and Kenya. And Poland, once thought to be a fully consolidated democracy, is now experiencing new challenges.

Russia’s failed attempt is a reminder that quasi-democratic states are also vulnerable to reversals. The term thermidor is associated with the French Revolution and the arrested democratization that followed the Reign of Terror and led to an emperor. Today’s version in struggling democracies appears largely to be a story of executive authority that is outsized in comparison to other institutions. The landscape is not devoid of independent forces, but the scaffolding supporting them has collapsed. They are increasingly at the mercy of the president. Any country’s institutional landscape will also include forces that are susceptible to populist appeals. Look closely at the constituencies that support Turkey’s Erdoğan, Hungary’s Orbán, and Russia’s Putin and you will see substantial similarities: older people, rural inhabitants, religiously pious people, and committed nationalists.

There are no claims here of universal truths in these examples. They are cases that I know well from personal experience and that illuminate important lessons about the path to liberty. In looking at them in depth we can see common elements as people seek to find the balance that all democracies pursue.

It is in that spirit that we will then turn to the Middle East. We have learned that revolutionary change makes the road to democracy hard—that the institutional landscape is unfavorable and that external powers find it difficult to help. Yet the Middle East is complex and the institutional landscape far more variable than we sometimes acknowledge. Its governments cover a wide range of regime types.

The region is a cauldron, but steps toward the establishment of democratic institutions cannot be indefinitely delayed. The stories of other transitions in less chaotic circumstances chronicled below hold lessons even for the Middle East. Collectively they tell a tale of imperfect people in difficult circumstances creating institutions that can slowly come to govern human interaction—peacefully.

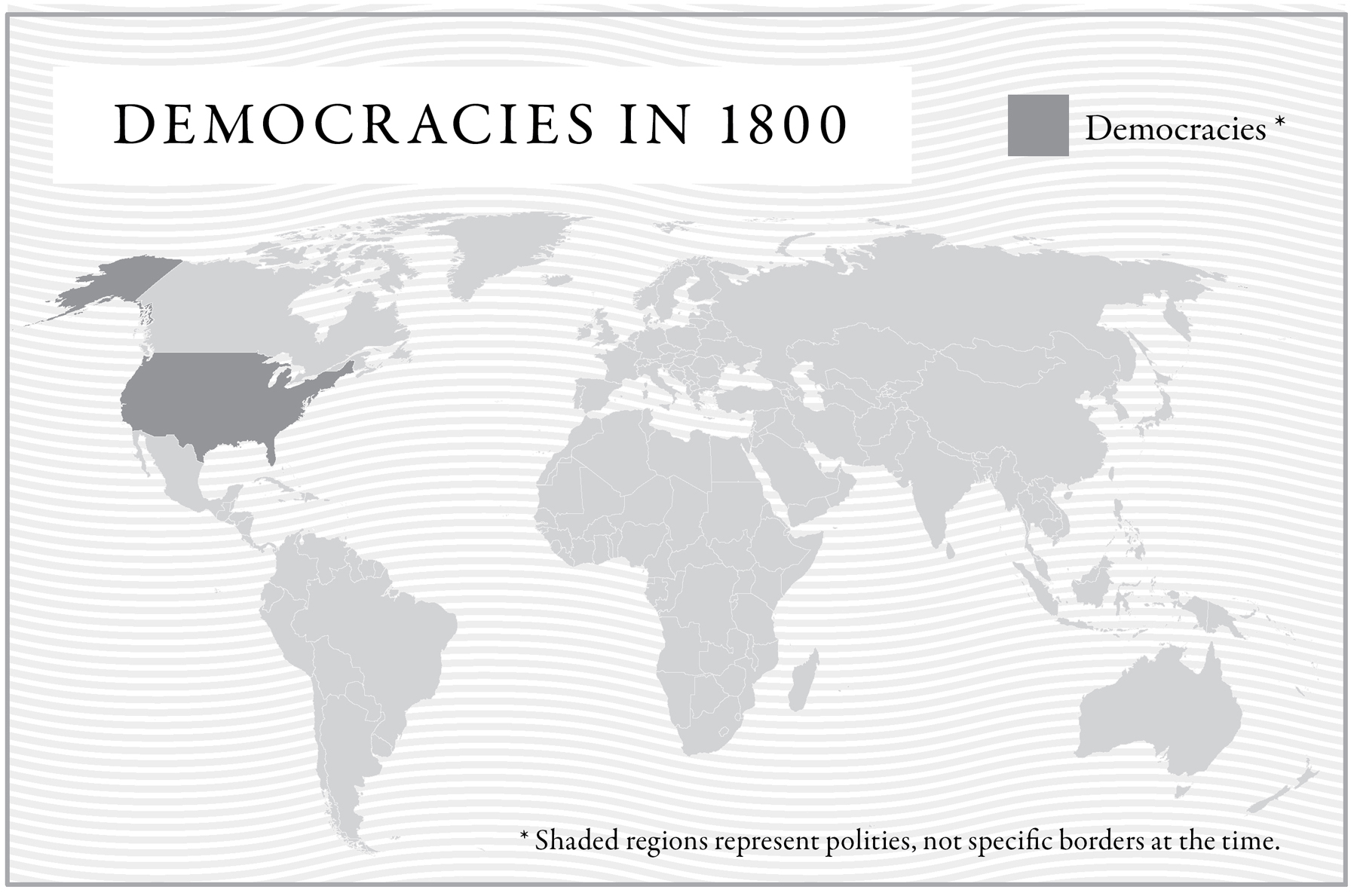

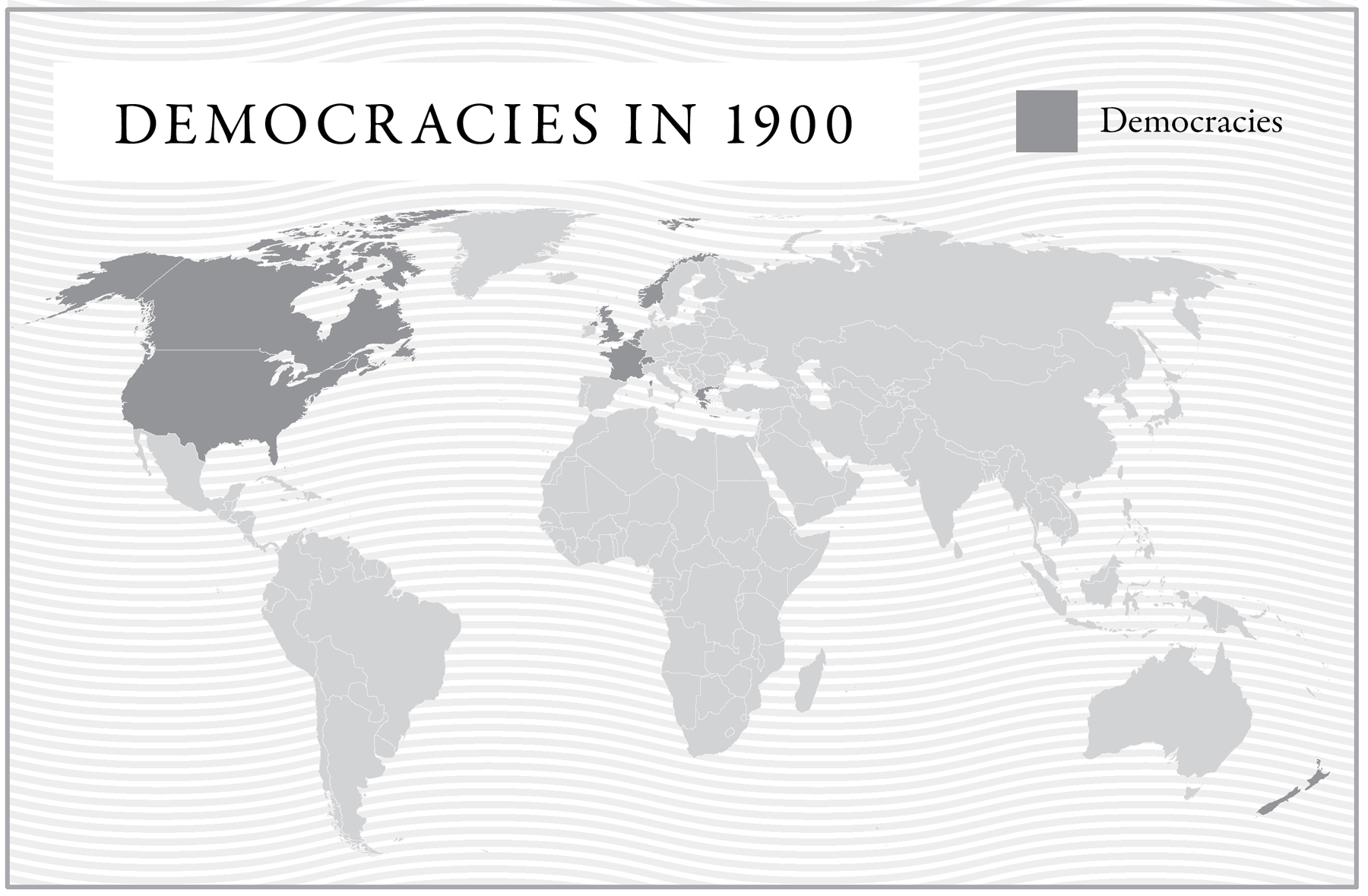

Data for the three maps that appear in this chapter are drawn from the following study, which classifies countries as democracies according to their levels of “contestation” and “participation,” terms first coined in association with democracy by the scholar Robert Dahl: Carles Boix, Michael K. Miller, and Sebastian Rosato, “A Complete Data Set of Political Regimes, 1800–2007,” Comparative Political Studies, December 2013, Vol. 46, No. 12: pp. 1523–1554.