TRISHA BROWN

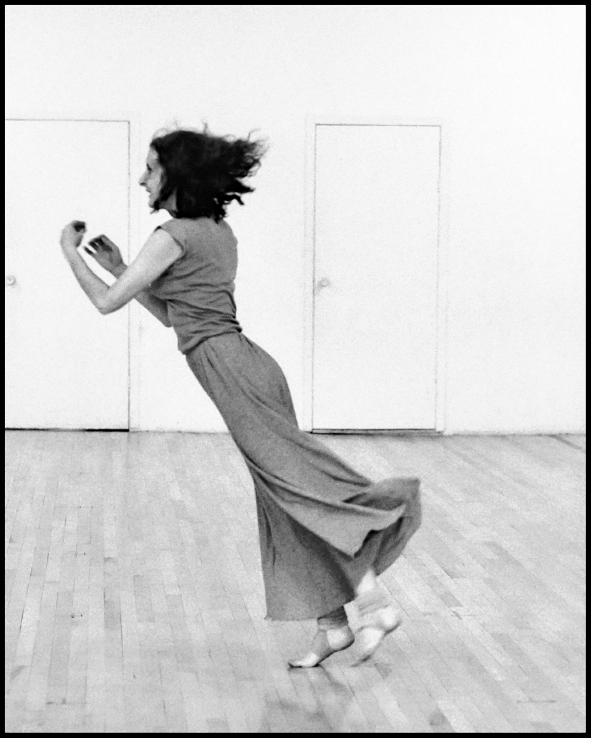

Trisha has a long, lean, collapsible body—almost gangly. She uses her arms sagittally, swinging them easily rather than extending line the way a ballet dancer would or sculpting space the way a modern dancer would. She can drop her weight all at once, or in segments, or she can suddenly seem to levitate. Her facial expression is plain but alert—no hoopla, no drama. But she sometime looks like she has a secret up her sleeve. She ties herself into pretzelly knots, often with Barbara, while working toward some impossible goal, for instance one dancer sending the other aloft. Her body needs no preparation to launch into something new, whether it’s a go-for-broke leap or little Geisha-like steps. She never looks lost; she always radiates a sense of purpose. You might see a glint of mischief in her eye that foretells some deflection or deception. She’s a trickster, that one.

Trisha Brown (1936–2017) grew up in the Pacific Northwest in an athletic, competitive family. Her older brother, part of an all-state basketball team, coached her and her sister in basketball in their driveway. He also mounted an ambitious, yearlong training of Trisha in pole-vaulting in her senior year, hoping she would make the Olympics.1 At the same time, she loved nature and walking in the woods. “The forest was my first art lesson,” she said more than once.2 She studied ballet, tap, acrobatics, and jazz dance in her hometown of Aberdeen, Washington, and later studied African dance with Ruth Beckford, a disciple of Katherine Dunham, in Oakland. After graduating from Mills College, which had a strong dance department, she accepted a teaching job at Reed College. Within a few months, she felt the existing methods of teaching modern dance did not help her students, who were not on a professional track, and started to teach improvisation.

As a child, she was already friends with improvisation. According to Jared Bark, who was her romantic partner in the early SoHo years, she described her ability to come up with a new game fast: “They’d be out playing, running around the streets getting bored like at the end of the day, and another kid would say, ‘What are we gonna do now?’ And she’d say, ‘I know what let’s do.’ And she told me, ‘When I started saying it, I had no idea. I was counting on by the time I got to do, I’d have something.’ She said that she looks back at that as the root of her improvisation: ‘I know what let’s do.’”3

In the summer of 1960 she took Anna Halprin’s workshop, which she described as “wide open improvisations day and night by very talented people.”4 There she met Simone Forti, Yvonne Rainer, and June Ekman. About a year later, Forti persuaded her to come to New York and take Robert Dunn’s workshop. Dunn’s classes supplied her with ways to frame her improvisations. She could devise a score as vague as “Read the wall” or as intricate as Rulegame 5 (1964), in which performers had to adjust their height level according to the pacing of others in adjacent aisles. (She attempted versions of those ideas with us in the following decade, when I was with her company, but neither of them panned out.)

Her ability to take time to sink into movement was a gift that I think affected her Grand Union colleagues in two ways: first, in the unrushed tempo, and second, in her willingness to stick to one thing for a long stretch of time. She didn’t just drop a gambit if it wasn’t working right away; she let it play out.

Brown’s verbal wizardry was another gift. With very few words, she could make a point. (I’ll never forget when she said to me, “The critics like their geniuses … few.”) Her voice was sweet and clear as a bell. She had a certain rhythm of speaking during Grand Union that was a mix of Zen patience and daredevil challenge. She might say one sentence or fragment, wait, listen, then say another. She had a unique way of forming spare, verbal phrases. (Having an English teacher for a mother surely helped.) Even in daily conversation, her words were always worth waiting for.

Brown could see any situation from a different point of view. She could see it slant. If someone was in a rut, she could do something to jostle that person into a new perspective. You might be deciding between Option A or Option B, but she would come up with option Z. She could be wickedly funny—or just goofy—in the service of her long-term project to re-see or re-define. One example was her piece Ballet (1968). She straddled two ropes, strung out about eight feet from the floor, awkwardly grappling with them on all fours—so much for the dainty virtuosity of that refined form named in the title.5

She had a wide dynamic range, deadpan notwithstanding, from restfulness or near stillness to what she called “the rapture” of improvising. She could appear to burst forth with joy. Her energy was contagious.

Trisha was always conscious of how she was communicating with the audience. In her solo Yellowbelly (1969) she demanded that the audience yell out the title word to activate her dancing. The audience eventually shouted the insult to get her to move, and she called that relationship “rough and symbiotic.”6 For Inside (1966), she improvised around the perimeter of the room near where the audience was sitting. “I added the problem of looking at the audience, not ‘with meaning,’ but with eyes open and seeing.”7 In her equipment pieces she changed the audience’s view radically. For instance, in Walking on the Walls (1971) at the Whitney, she created an illusion that felt like a hallucination for the audience. Watching it was so disorienting that it was hard to believe you weren’t looking straight down at a sidewalk. Very trippy.

Trisha had a moment on Halprin’s deck in 1960 that crystallized her sense of daring. She was performing the task of sweeping the deck, perhaps working on the idea of momentum, when suddenly the force of thrusting the broom catapulted her body into the air, parallel to the ground, propelling her into a crazy moment of horizontal flight. This was witnessed—and never forgotten—by both Forti8 and Rainer, who characterized it as “the mundane and spectacular all in one go.”9

A rare gift: Trisha came up with ideas that activated the entire group. In chapter 20, we’ll see how she sparked a delightful, funny, convention-flouting, witty, physical, celebratory sequence with a single suggestion. Even in duet mode, Trisha offered ideas that could be built upon. Whenever she was working with David, he was stimulated by her unpredictability. “She did the unexpected—gloriously,” he told me.10 He felt that whatever bid he tossed her way she could absorb, and whenever she initiated, “I could pick up on it and something would happen because of it.11

Trisha Brown in her studio, 1978. Photo: Lois Greenfield.

For Trisha, Grand Union presented an opportunity to improvise with others, which she never lost sight of. She watched, waited, and reacted. When she teamed up with Barbara, they sometimes looked like Rodin’s sculptures of wrestlers—and sounded like wrestlers too, with their grunts and groans. Other times they gave each other quiet suggestions for how to make a particular maneuver work. The trust between Trisha and Barbara probably solidified during the exhilarating—and harrowing—Falling Duet I (1968), in which each woman threw herself off balance, not giving a clue as to direction, thus challenging the other to cushion her fall at the last second. (This was one of the most hair-raising duets I’ve ever seen.)

Trisha’s ambivalence about being in Grand Union was no secret. She had wanted her own work—seventeen pieces up to that point—to receive more notice, but that didn’t happen until she attached herself to Yvonne Rainer’s star. Of course, ambivalence on the part of a single person can throw a wrench in the works of “togetherness.” But I would say that her ambivalence contributed to a certain emotional texture that scraped away any hint of an all-one-happy-family veneer.