SECOND WALKER ART CENTER RESIDENCY, OCTOBER 1975

The 1975 residency, October 5–10, drew on the popularity of Grand Union’s 1971 residency. The group held fewer site-specific events but offered more workshops. The performance series included a show in the Guthrie Theater at the beginning of the week, one in the Walker lobby at the end of the week, and solo shows by Nancy and Barbara in between. Audiences were not invited to join the performers, as they had been in the 1971 lec-dem; instead, people could take workshops with Steve, Barbara, David, and Douglas. Steve’s three-day video workshop at Minneapolis College of Art and Design generated video material to be used in the final performance in the lobby—a different form of community involvement.1

Both the Guthrie and lobby performances were videotaped, so I was able to see some of the consistent features of Grand Union’s work together: how the dancers’ restraint as performers tested the audience’s patience (as in the performance I described earlier that began with Trisha and David slowly inching around the perimeter); how they sustained parallel narratives (at times three couples engaged in three completely different tasks or fantasies); their brilliant use of props (sofa, suitcase, lamp, carpet, portable door, parasol, sticks, dollies, fabrics); and the confusing, sometimes disturbingly porous, line between private and public (the animosity between Gordon’s “character” and Dunn’s “character” could well have been rooted in real-life tensions). But most of all, I was able to absorb how the legibility of their actions allowed the audience to follow them wholeheartedly.

The scene that really took off, in which a single idea sparked a plethora of variations, inventiveness piled on top of inventiveness, with all players contributing equally, was the bowing sequence at the Guthrie. It all happened in one continuous flow of steadily building energy. Trisha started it. At a point when it was unclear whether the performance was over or not, she spoke into the standing microphone. In her clear-as-a-bell voice, she suggested, “Why don’t we take a bow and then start from there?” This ignited an eight-minute sequence of rollicking exuberance that seemed to emanate from a single choreographic mind. The audience response of clapping and cheering on cue helped make that little miracle possible.2

From watching two different camera angles (I’m grateful for the Walker’s archival diligence), this is what I saw: when Trisha proposes bowing, David happens to be standing behind her with his arm encircling her waist; as she bows, that makes a doubling of the action. The doubling idea ripples through the group. Steve gestures to Douglas, who comes from behind him as he bows. When Nancy walks forward to curtsy prettily, Barbara gloms onto her from behind. Trisha suggests “prancing into it and out of it.” David bounces gently in place, asking, “Like this?” To show what she means, Trisha backs up, then bursts forth, flinging her arms wide, galloping downstage toward the audience. Steve asks for “bow music” and immediately a sound track of an insistent tape loop is heard. It’s Steve Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain (1965), and it creates a crazed kind of momentum. Douglas initiates the run-and-slide bow. David shimmies his shoulders in a showgirl bow.

The concept of bowing shifts into any action advancing downstage and retreating upstage. The game has changed, and everyone onstage and in the house catches on. Steve pushes the sofa forward, with Trisha and David joining him. The three pull the sofa back upstage, just in time for Douglas to leap over it and dash downstage for a pirouette. Trisha slides forward on a sofa cushion as if sledding; Steve kneels on a cushion in mock triumph. They run back upstage; they tip the sofa over and—surprise—Nancy rolls out of it toward downstage. Barbara climbs on the sofa, prompting the others to form a shifting sculpture for her to walk on toward the audience. She steps on upper backs and shoulders. David rushes to pull over a portable door and other props to support her descent. Completing her mountainous trek downstage, Barbara somehow ends up upside down, very close to the audience. Wild applause and cheering for a mission accomplished.

They could have ended it right there, on a high—and the critics, no doubt, would have been happier. Instead, they slipped into a narrative of an unsettling argument between “father” and “son,” as played out by David and Douglas. It was one of those knotty times when they both seemed to be airing long-held hostilities. But the whole group took it in stride and ended up on the sofa in a relaxed moment of togetherness. The small suitcase that had been used earlier—Douglas and Steve had pulled a bolt of silk out of it, and Barbara had somehow gotten stuffed into it—was on the sofa, and Trisha tossed it out onto the floor. As the lights faded, David asked Trisha, “Why did you throw the suitcase over there?” Trisha: “I wanted to be able to get out fast.”

Trisha did want to get out, and she performed with GU only once more after the Walker.

∎

The following narrative unfolding is taken from the Walker Art Center’s archival video of the lobby performance on October 10. Without Trisha, who had to leave after the Guthrie performance, the group lacked a certain cohesiveness, and there was no moment when all the dancers fell in together as in the bowing sequence. At least one reviewer complained that it had too many endings.3 But this performance was full of transporting moments. A Mexican rug, a cowboy hat, and a swath of silk suggested faraway places and characters. Hanging from the ceiling in the center of the room was a tent-like canvas bag with two drooping sides. On the walls Douglas had pinned bags of leaves he had collected from Suzanne Weil’s lawn.

∎

Barbara stands upstage between a small Mexican carpet and a video monitor, lifting and tilting her head. Little white clips are attached to the outside of her knees. The audience trails in, chatting and greeting one another; foam cushions are handed out. Douglas, holding a cowboy hat, saunters toward Barbara. He stops; they lock eyes from several yards away, each slowly lifting one arm. Lithe and sensual, Nancy swirls a stretch of silk to the jazz music of Herbie Hancock’s Man-Child album and soon spirals her own body without the silk. Her swirling and spiraling through the space contrast with the meditative, rooted quality of Barbara and Douglas’s duet. Soon opposite qualities merge, and the dancers are engaged in a loose trio. Douglas gets restless, his long torso tipping and careening, hat still in hand. His limbs reach way out as though being pulled in several directions at once.

David appears in a long, cinch-belted yukata (the Japanese pajamas he brought home from his shopping trips to Japan). He’s inching along the floor, looking down at his feet, which are pushing something. He eventually arrives in the center and stands directly under the big hanging bag. The music has stopped. Nancy, using a stick as a cane, walks toward David, who has now wrapped that bag around his head. David to Nancy: “Don’t come in, I’m taking a shower.” [Laughter.]

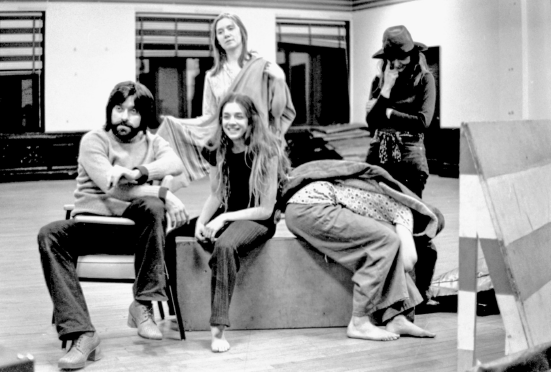

Gu in lobby of Walker Art Center, 1975. From left: Paxton, Dunn, Gordon, and Lewis. Gordon is about to bend down and move the stick. Photo: Boyd Hagen, courtesy Walker Art Center.

∎

Douglas covers Barbara, now prone, with the patterned Mexican carpet; he gets under it with her, cowboy hat now firmly on his head. Barbara is making quiet, wind-blowing sounds.

∎

Nancy offers her stick to David: “You want my crutch?” He takes the stick. They turn and walk slowly downstage. He places the stick on the floor, points to it, and asks her, “Wanna step over the stick?” They step over it together, ceremonially. He picks up the stick and lays it down again a few inches in front of them. They step over it again. He picks it up and sets it down again. It’s a very plain task yet a touching way of marking time going by. The familiar graduation theme (Pomp and Circumstance, March No. 1 in D Major, by Edward Elgar), is suddenly heard; the music swells, lending their slow, stately trek a certain grandiosity. After several repetitions, David indicates that Nancy should go out on her own. She hesitates, then bravely steps over the stick alone. As she walks away, he shouts out a send-off and gives her a salute: “Bye Nancy. So long Nancy. Take care of yourself.”

∎

Barbara enters and dances alone quietly, facing the audience. The lights dim so we can see that the white clips on her legs are light sensors. Steve joins her; in the dimness the light sensors seem to float. Another pair of floating glow-clips appears a few feet yonder. Nancy is wearing censors on her elbows as she windmills her arms. Still dim. We see the path of light sensors but not much else. Twilight. Barbara starts whistling. Douglas is jauntily swinging a bag of leaves. He slows down and pours the leaves out of the bag, center stage. With his foot, he pushes the leaves into a neat circle.

David: “That’s almost irresistible.”

Douglas: “What’s the almost?”

Steve: “Is somebody in that bag?”

Douglas: “I didn’t look.”

Douglas (perhaps): “Its rigged.” [A play on words, since the canvas bag is rigged from the ceiling.]

Steve: “I want to kick them.” [Meaning the leaves.]

Douglas: “It’s almost irresistible…. It’ll be interesting to see if anybody kicks them before the evening’s over.”

David: “How interesting?”

Douglas: “More than almost interesting.”

∎

Barbara is softly hooting. Steve starts talking about an ice cave caused by five hundred acres of lava, near a volcano that could erupt any time.

David, while assuming one position after another: “This isn’t the story that ends with you running over your best friend, is it?” [Laughter.]

Steve launches into a different, much longer story, as he walks around the perimeter, indicating it’s a field. This story, about baling hay, is rich in detail—all the stages of cutting, rolling, conditioning, fluffing, and packing the hay onto a wagon—but delivered in a monotone. The upshot is that the hay is packed so tight that a snake, stuck halfway out of one bale, cannot wriggle all the way out. During the storytelling, Douglas slithers bonelessly.

David: “Sounds like a good story for a ballet.”

Steve: “If you would care to do a ballet to my story, David …”

David, pointing to Douglas and his snaky movement: “It’s been done.”

Intermission.

∎

Steve and Nancy lounge on the sofa, watching a television monitor. [I believe the video loop, which includes someone tying shoelaces, is a product of the video workshops that Steve taught.]

∎

Under the parasol, Barbara and Douglas inch forward on their knees.

Barbara: “Hark, that must be the sound of a babbling brook. It must be water.”

Douglas suddenly rises and brandishes the stick. “No water, I think it’s the enemy. We must prepare.”

Barbara: “I’m afraid. What do I do now?”

Douglas: “First consider that we know they are within earshot.” He strikes the parasol with the stick.

Barbara: “I think I better put down my red umbrella.” As she slowly lowers the parasol: “Will you … hide me … from the enemy?”

She takes the umbrella, now collapsed into a cone, and lies down on the sofa, which has just been vacated by Steve and Nancy.

∎

Douglas whirls a big platform the size of a double bed around so forcefully that it knocks loudly against the floor. Barbara is raking the leaves into one long line that bisects the performance area. Nancy sits absolutely still on the dolly, holding a long twig upright. A bandana covers her face.

∎

Steve: “Tell me a story, David.”

David: “A hand for your heart. This is the heart.”

Steve: “Where’d you get those shoes?”

David: “I want to talk about something poignant like my hand on your heart and you want to talk about high fashion.” [Laughter.] “I want to bring a little emotional content to this concert. Could you please put your heart in my hand.” He reaches his palm outward, just a few inches from Steve’s heart.

Steve: “Sure.” He steps closer to David but pushes his hand to the side. Not what David had intended. [Laughter.] Barbara brings over a mic and puts it up to David’s mouth. He breathes heavily into it. “Thank you, that’s all.” Barbara walks away.

David brings his palm up to face Steve again. “If you will not fall toward my hand, will you fall away from my hand?” He softly slaps Steve’s cheek.

Steve falls away from the slap, and David catches him with his other hand and sets him upright. David raises his palm above his forehead. Steve jumps up as though to place his heart on that hand, which is of course too high. After a couple more moves wherein they fake each other out, David lies down in an open position, vulnerable. Steve gets down on the floor next to him, belly down.

David softly: “Steve, I can hear the beating of your heart.”

Steve sits up: “I turned it on for you. Want me to turn it up a little bit?” He goes back to floor and exaggerates a vigorous, repeated chest bump.

∎

Douglas scoots Nancy’s dolly close to the central hanging bag. He places an electric fan near her. Nancy drops her stick—the first movement she’s done in about fifteen minutes. Douglas lifts the fan and puts leaves in front of it to blow them toward Nancy. A flurry to awaken her from hibernation. But she doesn’t move.

∎

Steve is sitting on the floor. Barbara walks toward him from behind. Without looking up, he lifts his arms to hold her hands, and they start dancing softly together.

JOAN EVANS AND CENTRAL NOTION CO. BY JOAN EVANS

In Grand Union’s heyday, its members were invited to teach in New York University’s dance department. Joan Evans, who was a student at that time, was so inspired by the group’s lessons that she cofounded a collective performance group in their image, Central Notion Co. A former dancer/choreographer, Evans is now an award-winning director of physical theater. She is also head of movement at Stella Adler Studio of Acting in New York City as well as artistic director of its Harold Clurman Center for New Works in Movement and Dance Theater (aka MAD). Knowing how much she was influenced by Grand Union, and wanting to include some sort of nonprescriptive information on educational methods, I asked Evans to write about her experience with them.

In 1972, when I was a graduate student at NYU School of the Arts, the acting director of the dance program was Helen Goodwin, who had been influenced by Anna Halprin. She had the brainstorm to arrange for us to work with the artists in Grand Union. The classes met at 112 Greene Street in SoHo, in a large raw space on the ground floor. Barbara Dilley and David Gordon were our primary teachers. While their teaching styles and artistic interests were different, the one lesson they both focused on was how to perform. Barbara talked about “being in the moment” or “just being,” by which she meant open and aware, until something or someone moved you to join the improvised dance. David instructed us to be more “workmanlike.” He taught us short, horizontal walking patterns with frequent changes of direction and focus. When doing this, we had to put all our attention on the work.

Trisha Brown introduced her ideas about interruption. An interruption refocused or completely changed the movement or moment by providing conflict or contrast, a rhythmic shift, and dynamic change. Interruptions helped prevent the material from becoming stagnant.

Central Notion Co. at NYU dance department, 111 Second Avenue, 1972. Sitting from left: Gordon, Joan Evans. Standing from left: Fran Page, Donna Persons. Louise Udaykee is bending over. Photo: GregoryX (Gregory Schmidt).

We had one peculiar class with Steve Paxton. We heard Steve would be teaching and we looked forward to the opportunity to do Contact Improvisation. However, we were all quite sick with colds that day, so Steve brought us upstairs to Jeff Lew’s loft and taught us how to clear our sinuses using a saline solution. It proved quite effective.

Yvonne Rainer taught us pedestrian movement sequences at the loft and then engaged us in a game of stick ball between the parked trucks on Greene Street.

Nancy Lewis (then Green) didn’t teach us, but she invited me into her home when I needed one to keep working. As a performer, she was an extraordinary inspiration. The fluidity with which she moved her upper torso encouraged me to develop more suppleness in my own spine, and later incorporate that work into my teaching.

The NYU dance students performed, alongside many other people, in David’s piece, The Matter, in the spring of 1972 at the Cunningham Studio. We learned about tableau and gesture. At the conclusion of the NYU spring term and the run of The Matter, five of us from that class formed Central Notion Co: Fran Page, Donna Persons, Louise Udaykee, Fern Zand, and me.

We attended many Grand Union performances in New York. The performers would arrive at different times and warm up or set up while talking to each other. They stretched the boundaries of dance by simultaneously engaging in witty dialogue, creating designs with whatever was in the space, and dancing together in a gloriously free structure. Sometimes everything happened at once, and sometimes a climactic scene emerged, which seemed to bring all the separate elements into agreement in an almost operatic way. On several occasions, Harry Nilsson’s passionate song “Without You” was played in the background.

Central Notion Co. modeled itself after Grand Union. We improvised dances and dialogues, and experimented with objects, set pieces, and costumes. Sometimes, multiple things happened at once, and other times we collaborated on a single motif.

In addition to being colleagues and collaborators, we were also close friends. Our lives and love lives were all intertwined with the work. We hurt each other’s feelings and had constant feuds, but making up, which often happened onstage, made for good drama, and an overall intensity, on which we thrived.

We thought that we would benefit from some more guidance, so we asked David and Barbara if they would continue to mentor us after the NYU course ended. We rehearsed and sometimes performed at NYU at 111 Second Avenue in the East Village. David worked with us once a week for a full year, and Barbara met with us once a week for about six months and then whenever she was not traveling. David served as an outside eye, whereas Barbara provided leadership within the improvisation itself.

Barbara had a gentle manner, and we rehearsed more quietly on the days when she was there. Whenever she saw elements that were missing or uninteresting in our improvisations she set up structures to help us. She taught us that space could be an important element in our collaborations. How we saw the space would determine how we related to each other and the type of movement we would do. In one of my favorite sessions, she designated the space as a series of corridors. We each had to stay within our individual lanes and pick up signals from one another, peripherally. We learned to listen not only with our ears and eyes, but with our whole bodies.

Barbara also taught us lessons that extended outside the work. She was accepting of us and wanted us to accept ourselves as well. She encouraged us to trust our instincts and each other. Barbara seemed enlightened about life and was very calm. We all wanted to be around her and saw her as a strong female role model.

Barbara Dilley with Central Notion Co. at NYU dance department, 1972. Photo: GregoryX (G. Schmidt). Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

We met with David every Tuesday evening. He watched us carefully and then critiqued our sessions in detail. He was truthful and tough, and his comments sometimes stung. He had no tolerance for coyness and would tell us when we were boring. When he liked something, he pointed it out. David demanded we be honest; he reprimanded us when we were false or lost our concentration. Many years later, I realized that David was not just teaching us how to improvise and how to perform, but intended or not, he was helping us develop taste.

David knew how to spontaneously create a scene, and also when to let go of an idea. He challenged us to do the same. He wanted us to develop a sense of how long was enough and what was too long, and to learn to build a scene to a climax. When we were just spinning our wheels, David would sometimes enter the playing area and do something dramatic like start a dance or add objects to the space. Mats and other objects were readily available since we rehearsed in the theater space, where clown and combat classes took place. (All programs in the NYU School of the Arts operated under one roof in the early seventies. In 1982, when it was named Tisch School of the Arts, most of the other arts programs moved from Second Avenue to 721 Broadway.)

One night, David arrived with vintage khaki raincoats and hats that sparked our creativity. We used them to improvise a noir-like scene that we incorporated into our upcoming performance. David liked what we did.

David was very generous. He talked to us about performances he had seen or artists he knew and told us funny stories. He introduced us to his family. At holiday time, he gave us all beautiful long wool scarves. David and Barbara also arranged for Central Notion Co. to perform at a two-month festival that Grand Union members had organized at the Larry Richardson Dance Gallery. [See chapter 15.]

During that time, Central Notion also performed on the Staten Island Ferry, at The Performing Garage on Wooster Street, and at the Hudson River Museum. Fran left the company soon after and settled in Colorado, where she founded the Aspen Dance Connection. Fern left the following year to dance with Rudy Perez, one of the Judson dance artists.

Our all-female company changed further when Bill Gordh, storyteller and musician, joined the company, along with Gregory Schmidt, who played piano and saxophone. We toured to The Theater Project in Baltimore and Wilma Project in Philadelphia.

The summer after Barbara Dilley moved to Boulder to develop the dance program at Naropa, she invited Central Notion Co. to perform there. I recall that Douglas Dunn was out there then, and he attended a performance.

Helen Goodwin stayed in touch with us when she returned to Vancouver, and in the summer of 1974 she arranged a tour for us to British Columbia. Donna, Louise, Bill, our manager Tom Jenkins, and I set out west in a Greyhound bus. We had four performances in three venues but they were spread out over a month. We ran out of money at the end of the tour, so we divided up into pairs and hitchhiked back across Canada to New York City.

In 1975, I created my first set piece, a solo called Dinner and the News, and stopped performing with the company. The following year, Louise and I made a duet called Two Women Perform a Romance for the New Depression. I choreographed theatrical dance solos for nineteen years, and I often improvised for months before setting the movement or engaging a director. I began creating and directing ensemble physical theater work in 1996.

In 2012, David asked me to choose four of the Muybridge poses from The Matter and have myself photographed doing them. That fall he used my photos and those of other performers from earlier versions of The Matter in a new live performance as part of the Danspace Project’s series commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of Judson Dance Theater. Forty years after I appeared in the 1972 version, David once again invited NYU students to perform in the piece. Coming full circle, one of those 2012 performers—Madeline Mahoney—happened to be a student of mine at NYU Tisch Theater.

Barbara and David’s teaching influenced mine. When I coach actors, I encourage spontaneity and impulsiveness. My students must learn to be spatially aware and listen intently. I instruct them to focus on their partners and on the action, rather than on their feelings. I teach them to engage their physical imagination and explore a moment through improvisation. I developed my own technique to teach these fundamentals. While the language that dancers use may be different than the language of actors, the core values that I learned as a dance student are also applicable in actor training. An honest, imaginative, and responsive performer is a good performer in any medium.

Actors need to transform to play characters. I teach my students to begin by being aware, open, and fully present, what I call “neutral”—and that’s pure Barbara Dilley! A neutral starting place facilitates the magical union of belief, imagination, and self, which gives birth to the character. Otherwise the characterization is contaminated by the actor’s own habits and limitations.

When we were working on The Matter, we had to hold still mid-stride. Back then, we just tried to keep our balance and not get tense. Now I teach my students about “active stillness.” While still, the character is a thinking, breathing person whose needs and intentions are ongoing in stillness. We probably would have found performing in The Matter easier had we known about active stillness in 1972.

Starting out as an improvisational performer made the transition to choreographing a natural one. Now, when I devise ensemble pieces, I generally start with an image and then develop the material with the actors, who improvise. I give more direction, and then we repeat that process several times. I choose what I like, develop the material further, and become extremely specific in my direction. Above all, I remind my actors to stay present, for that is the most important lesson I learned from studying with Barbara and David and watching the Grand Union perform.