THE DANCE GALLERY FESTIVAL, SPRING 1973

Perhaps spurred by the success of the Walker and Oberlin residencies, the Grand Union dancers (without Yvonne, who had left the group to make films) decided they wanted to perform more. They applied for a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts, rented the Larry Richardson Dance Gallery on East 14th Street for two months, and performed seventeen times during April and May 1973. (How did they get through that many improvised performances? Steve emailed: “We plowed through.”)1 To fill in the nights they weren’t on, they invited more than twenty guests, mostly old friends from the Judson days like Deborah Hay and visual artist Alex Hay, as well as theater group Mabou Mines, dancer Carmen Beuchat, and musician Dickie Landry, to perform one or more times. David Gordon had a solo night. Nancy had a night with musician Richard Peck in which they invited other artists and musicians onstage. Steve’s “collaborative ensemble” from Bennington, where he was teaching, gave two performances; so did Barbara’s offshoot group, the Natural History of the American Dancer.

This two-month marathon was similar to the Walker and Oberlin residencies, but on the group’s home turf. The Grand Union had to supply consistent activity and interact with the community. They relied on the willingness of the SoHo “tribe” to be part of an exchange in which they alternated between performing and spectating.

Deborah Jowitt expressed a wish to see all seventeen GU performances. But she wrote a wonderful review after just one, noting that GU eluded the common pitfalls of improvisation:

[T]hey don’t affect any of that false intimacy that some actors and dancers use. Nor do they jump about from one thing to the next, trying to introduce contrast or draw audience attention. They take all the time they need to let something evolve naturally, without doing too much on-the-spot editing or juicing up of their activities. There is something very unselfish about them: they find satisfying ways to join something that they themselves might not have chosen to do—perhaps out of love or respect for the person who started it.2

Jowitt also enjoyed the fun stuff—“a fantastic human pyramid and a lot of very funny dialogue about a family of circus acrobats (maybe)”—as well as the everyday casualness of what they chose to do. She felt that the dull moments were more than offset by the intimacy they projected: “Certainly they can be boring, strained, or arch. But if you were fond enough of them to see a lot of their performances, you’d accept their limitations or low points the way you accept the inadequacies in a person you love.”

Nancy has a memory of a Dance Gallery performance that illustrates how involved the audience was. She remembers Trisha walking atop the ballet barre that lined the room and how, when she came to a space between the barres, “it would be nearly impossible for her to navigate! But someone would come flying across from the other side of the space—Steve or Doug—and the audience heaved a sigh of relief.”3

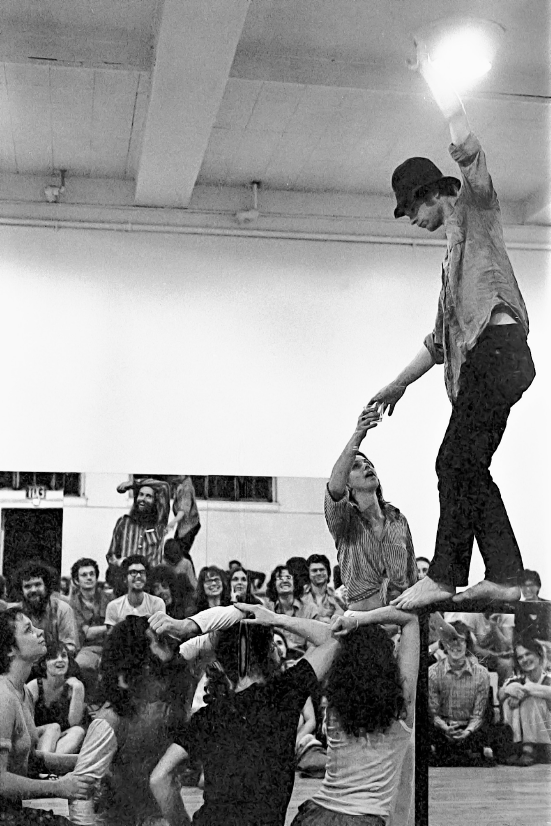

On another occasion, Douglas, walking precariously on top of that barre, announced that he was thirsty. Someone from the audience offered a cup with a little bit of water in it. Nancy took it and held it up to him. He drank the water, then tossed the cup down.4

Grand Union not only invited others to have their own evening, but also invited guest artists to enter into its performance. The members were still curious about what it would be like to work with colleagues who could potentially mesh well. Two of the mostly likely were Lisa Nelson and Simone Forti, both of them daring and sensitive improvisers. And for both, the experience was a dead end.

Lisa had been working with Daniel Nagrin’s Workgroup, which in 1972 had more theater than dance people in it. Nagrin had come to watch GU at LoGiudice Gallery, possibly because Barbara had been in his company before she joined Cunningham. Lisa remembers Nagrin and some of the others in the Workgroup talking about GU, but she had not yet seen the group. She had met Steve while they were both teaching at Bennington the spring of 1972, and they easily landed in a studio improvising together. She was (and is) a superb improviser with a kind of animal nerve center. But she’s not a talker onstage, and when she came to the Dance Gallery, David’s verbal attempt to make her feel welcome backfired. She ended up sitting out most of the evening.5

GU in Dance Gallery Festival, 1973. Dunn on barre, Lewis handing a cup of water up to him. Below, from left: Dilley, Gordon, Forti (as guest), Brown. Photo: Tom Brazil.

GU in Dance Gallery Festival, 1973. From left: Dilley on floor; Lewis; Forti, as a guest artist, wearing blindfold; Gordon. Photo: Tom Brazil.

Simone had worked closely with Steve and Trisha, both of whom have said they were artistically indebted to her. But while actually performing with GU, she reacted with ambivalence. She perceived the kind of “going toward nonsense” in the spoken material as similar to a strain of the work with Halprin in the late fifties that she had gotten exasperated with. At that time she felt the Halprin verbal engagement had become surreal and not grounded in people’s feelings. When she encountered this brand of cleverness in GU, she had an opinion: “I was very stuck up about it,” she said later. “I thought this is old stuff that they’re doing.”6 But she became unexpectedly emotional. “I was crying onstage in performance because I had walked away from that. I couldn’t go back to it. I now wish I had.”7

Another, more unlikely guest was composer Bob Telson, a musician immersed in classical as well as jazz forms. As a student at Harvard, he had played for dance classes at Radcliffe, including when Dilley was guest teaching. Later, his group of jazz musicians and Barbara’s group the Natural History of the American Dancer (at that time consisting of Dilley, Lewis, Cynthia Hedstrom, and Mary Overlie) improvised together once a week in his loft in Tribeca. In that merged group, called the Collected Works, sometimes “a couple of us musicians would get out there and move too…. It was a free-flowing thing that was definitely in the spirit of the times.”8 The Collected Works earned a spot in the festival, but in addition, Telson was invited as a guest in one of GU’s own performances.

About Grand Union’s experiments with new people, David recalled, “It never worked. We had turned into a closed shop somehow.”9

Nancy remembers the way one particular evening ended: “One night as we were trying to figure out how to end our performance, I felt bad about something I thought was not very good about my performance. So I went to lie down under a bench that was against the wall. Steve came over and lay down beside me, almost squeezing underneath me. Then Barbara came, and then Trisha and David sat down on the bench. It was a good ending—sweet and compassionate.”10

That moment was caught in a photograph by Cosmos and put on a little comic strip publicity flyer. Nancy added the words, “What are you doing after the show?” as though David were asking Trisha, sitting on the bench.

The festival also gave GU members a chance to engage in their most radical acts. For his April 30 solo night, Steve continued his interest in censorship. His earlier piece, Beautiful Lecture, which juxtaposed a porn film with a film of the Bolshoi’s Swan Lake, had been forbidden when he first proposed it to The New School. In response, Steve had replaced the porn film with a documentary about people starving in Biafra. As with Intravenous Lecture (mentioned in chapter 8), he was asking, What, really, is obscenity? For the Dance Gallery version, titled Air, he kept the ballet/porn film pairing, with himself “writhing between them.”11 He also incorporated something very of-the-moment and obscene in its own way: President Nixon’s first deceitful Watergate speech (“There can be no whitewash at the White House”), played live, that night, on a TV set.

Graphic from GU in Dance Gallery Festival, 1973. From left: Dilley, Paxton, Lewis, Gordon, Brown. This was the last image in an accordion-type flyer designed in 1973. Photo: Cosmos; graphic by Artservices; words by Nancy Lewis.

A former member of GU reentered the fray during the festival with her own radical act, so to speak. Writing in the New York Times, Don McDonagh noted “as an unexpected added attraction, Yvonne Rainer doing a stripper’s bump and grind with wit and verve.”12

The festival didn’t really have a name, but the blurb on top of the poster reads: “Grand Union and friends and associates in two months of performing and carrying on!”

And carry on they did. Possibly the best record of their raucousness is this passage from Sally Sommer’s notes about the time that David and Steve had come to the theater dressed as “twins”:

Nothing was working. No one connected. Nancy was obsessed by the hundreds of square pillows. Trish joined her by lying on a stack of them. Nothing. David dropped some of them on Trish. Nancy threw more. Barbara sat on a stack of them. Nothing. Barbara retired. Trish got up to do a duet with Nancy. Nothing. David launched into a TV game show with Nancy and Steve as a soon-to-be-wed couple. More attempts to connect with each other. (Trish to Steve: “Where am I? What the hell am I doing here?”) Old gymnastic tricks with a ballet barre. Something, but not much, except Steve’s pants rip wide open at the crotch. David offers his pants but Barbara offers both the matching skirts. Steve: “I’m game.” They rush off. Hungarian music. Will anything work? Suddenly David and Steve burst out into a mad, exhilarated, bizarre, distorted, quasi-cossack rough-and-tumble melee. It’s funny but just as it might get cutesy drag funny, Steve begins some dangerous flying leaps over the barre and then grabs David into frantic spins … flinging him off the floor into the air, plunging him back down … twirling, twisting, dangling, tangling, … but never stopping the frantic dervish of whirling bodies. Collapse. They finish. It worked. Like a volcanic eruption, it worked.13

Although moments like these were wildly appreciated, the series was financially a bust. The modest grant from the New York State Council on the Arts barely covered the costs of presenting such a long, complex season, and very little other money, either earned or unearned, was coming in. The upshot was that the dancers were paid only a fraction of the amount projected.14 But there was this: although only forty or fifty people came most nights—and they tended to be the same people—on the last night of GU’s performance, more than two hundred people crammed into the space, lining the staircase as well as the downstairs level.

DOUGLAS DUNN ON THE “SELFISH/SELFLESS GAMUT”

The following excerpt is from Dancer Out of Sight: Collected Writings of Douglas Dunn.

As a post–World War II California kid I attended a progressive grammar school where teachers let us run wild but intervened to identify individual versus collective priorities. Learning to distinguish between my and others’ needs and desires turned out to be relevant everywhere: on athletic teams, on boards of directors, in subway cars and in dance companies. Grand Union provided a hot caldron for exploration of the selfish/selfless gamut. Deciding to perform without rehearsing meant more than a lack of preparation—it meant absolute freedom. It meant that “nothing has to happen/anything can happen” was now bounded only by each individual’s range of fantasy and courage. Both had fenced limits within me, some already there, some defined by what I knew or imagined others present would dislike. Dancing with Grand Union extended the terrain inside the fences.

Doing what one wants to do in private is one thing, performing in public another, and performing in public in cahoots with colleagues—people with whom one had, to boot, off-stage relations—yet another. One minute we might choose to develop the most benign kind of movement or verbal relating, using a brand of ironic deadpan we often favored which undercut, sometimes by exaggeration, conventional modes of pandering. The next we might thrust ourselves at one another physically in potentially dangerous forms of partnering, or bring up painful personal information, testing whether the other could stay in character sufficiently to handle the heat.

On a good night I had not a single front brain thought for the hour or two we were out there, went instead from one simple or complicated or outrageous activity to the next as if every word and move had been choreographed, as if instincts of the kind that make animals’ actions appear assured were guiding me. Hindsight tells me I was, to keep fear at bay, riding two unconsciously conjured clouds of “confidence”: the first, that deep down others were not out to “get” me; the second, that no matter what might happen, I could hold my own.

What evolved and remains is a self-reliance grown sturdier through dealing with consistently unruly circumstances. Also, a belief in the synergistic potential of “performed” interaction … that deepened through gradually realizing just how complex and radically surprising was our collaboration. I am forever grateful to each Grand Union dancer for daring to participate in this profoundly life-expanding adventure.

Reprinted with permission from Dancer Out of Sight: Collected Writings of Douglas Dunn (drawings by Mimi Gross; designed and produced by Ink, Inc., New York, New York, 2012), 139.