NANCY LEWIS

With her long, sensual limbs and natural verve, Nancy Lewis is a knockout of a dancer. She has an offhand luminousness that is refreshing in the context of the more interior focus of other Grand Union members. She can start dancing with the merest hint of a shiver and gradually let it take over her body until she gets carried away into a legs-swinging, everything-at-once dance. Her gamin face holds mischief just beneath the skin. Her intuitive, spontaneous wit lends her a campy, femmy, “Who, me?” goofiness. In Grand Union performances, she exerts less of a sense of intention than the others. But she can take your breath away with a quick, unfiltered response—or simply with her dancing. She’s a team player, a fresh spirit, and a memorable character.

Nancy Lewis (born 1939), who lived in New Jersey until the age of six and then in California, was always athletic: she joined the diving team in high school; she hiked and skied the nearby mountains. She started dancing in high school and attended American Dance Festival at Connecticut College in the summer of 1958. There she studied with Lucas Hoving, one of ADF’s beloved teachers/choreographers. Hoving had created major roles in José Limón’s repertoire and had developed his own blend of classical and modern dance technique. His signature work, Icarus (1964), has been performed by several companies, including those of Ailey and Limón. Hoving had an eye for talent; around the same time that Nancy was a promising student, he arranged for another teenager to attend Juilliard: Pina Bausch.

In her first year at Juilliard, Lewis remembers that Alfredo Corvino, master Cechetti teacher, said to her, “Why are you so relaxed?”1 She didn’t know if he was alarmed or admiring, but she clearly did not have the formality that is usually instilled during ballet training. Helen McGehee, one of the most austere of the Martha Graham teachers, also noted her as unique.2

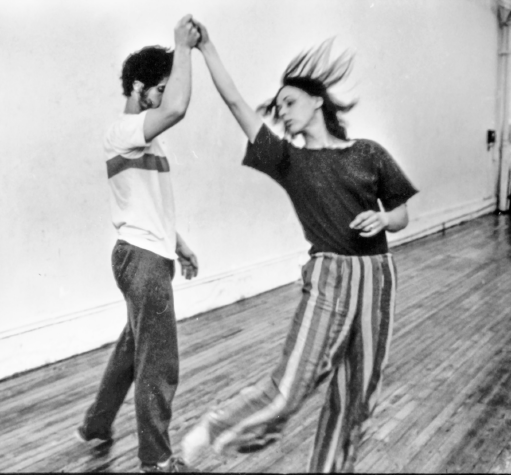

Nancy Lewis with Steve Paxton. Photo: Robert Alexander, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Even though she received positive attention at Juilliard, Lewis left after two and a half years to study with Merce Cunningham. She gravitated to his work, and he to her. She was tall, attractive, flexible, and had a languid, louche style that in some ways anticipated that of Karole Armitage. But just when he was about to invite Lewis into the company, she got pregnant. (She had married Dylan Green, an actor, in 1962.) After her first child was born, she worked to get back in shape until Merce was about to ask her again, then had a second child. After the third child, it was over between her and Merce.

In the summer of 1960 at ADF she danced in Jack Moore’s new duet Songs Remembered. She portrayed a kind of lost love in a duet that critic P. W. Manchester later called a “heartbreaker.”3 In 1964 in New York, she danced the shimmering Sun in Hoving’s Icarus. I will never forget her in this role. She commanded the stage in a slow walk, each leg turning inward, then swiveling outward before taking the next step. With just a small pulsating of her hand, palm outward, it seemed that she was sending out rays of light.

In some ways Lewis had the most to lose by joining Grand Union. The group’s aesthetic was far from her Juilliard training. While Paxton, Dunn, and Dilley had all danced with Merce Cunningham and absorbed the Cage/Cunningham aesthetic, Lewis had been performing works by choreographers more aligned with “historic” modern dance, like Hoving, Jack Moore, and Anna Sokolow. (She had also danced in Twyla Tharp’s Group Activities [1969]) and The One Hundreds [1970].) In fact, Hoving and Moore had both served on the panel of the 92nd Street Y that had rejected Yvonne Rainer and Steve Paxton for its Young Choreographers series. They were so angry with Lewis for decamping to the downtown aesthetic that neither of them ever came to see her in Grand Union. This was a bit sad for her and shows how much of an aesthetic gap she was bridging.

Whenever Lewis danced, people noticed her. At Juilliard, it was her teachers; at ADF, it was Jack Moore and Lucas Hoving. At the Cunningham studio, Barbara Dilley noticed her. In fact, it was Dilley who recommended Lewis to Rainer when the CP-AD group was opening up to new dancers. And then Rainer remembered seeing Lewis at ADF at Connecticut College in 1959 in a piece by Jack Moore. Almost sixty years later, her memory of that performance was so vivid that she imitated for me Nancy crazily moving her malleable mouth with her hand.4

Lewis had no training in improvisation, but she remembers improvising as a child on swings and in small performances. According to her older son, Miles Green, she was known as the entertainer in her family.5 (One could say her talent as a performer runs in the family; her son Miles is a musician and her niece, Juliette Lewis, is a Hollywood actor.) As a dancer, she felt a natural tendency to improvise but “never found anyone to perform it with” before Grand Union. (It’s actually remarkable that she could hold her own against the others, who had either been through CP-AD or, like Brown, had been improvising in their own dances for years.)

In performance, Nancy responded quickly and intuitively to any overture. If David said to her, “Don’t come in, I’m taking a shower” (as he did in Minneapolis), she immediately conjured a bathroom and played into his fantasy with subtle humor. At La MaMa, while tied to a cross, she improbably caught, in her mouth, a chunk of grapefruit tossed in her general direction.6 At LoGiudice in 1972, when Paxton put the mic up to her face, she instantly summoned a Loretta Young–type glamour as she gave spontaneously trivial answers. Lewis was a chameleon with star quality.

According to critic Marcia B. Siegel, “Lewis is … the possessor of the quickest imagination. She can become a sylph or a monster or a Grecian shepherdess just like that, can vocalize like a Moroccan at prayer.”7

The chameleon ability was also noticed by Deborah Jowitt. In 1973, when Lewis was still using her married surname Green, Jowitt wrote, “Gordon and Green together can be outrageously flamboyant and play with all kinds of theater styles; Green with [Douglas] Dunn becomes more of a sober crazy-legs like him.”8

Nancy could always be counted on to dance. In a performance at Oberlin, she danced to Ravel’s sixteen-minute Bolero alone. Somehow the other dancers knew that this moment was destined to be a solo, and they backed away. Yvonne remembers that solo as a high point: “That scene is riveted in my mind. I thought her dancing was ravishing…. It was a highlight of that performance. With all the disparate, non-sequitur things going on, there was this.”9

But Lewis looks back on those sixteen minutes with distress. “They turned on Bolero, and I was out there, and it was for me to dance to Ravel, and I hate that piece and it’s long. I had to bop around the length of that piece, in this huge gym, and it was just the worst time I ever had in a performance.”10

This dazzling dancer could sometimes just be still for a long time. On occasion, it felt like a retreat, for instance in the 1975 Walker Lobby performance. (A full description follows in chapter 20.) Or a dare that wasn’t fulfilled, like the time at LoGiudice when she sat still on the floor, topless, in a loose embrace with Paxton—and no, it didn’t go anywhere. But these episodes showed an acceptance of simple presence as part of the dance.

Knowing she was more of a performer than a choreographer, Lewis organized her own repertory concert in 1971 at The Cubiculo, a small midtown theater that presented many modern dancers (including myself) in the seventies. She performed short works by Rainer (Three Satie Spoons), Paxton (Smiling), Gordon (“Liberty,” an excerpt from his Sleep Walking), and Moore (Clown Vice), and improvised Prelude-in-Sneaks, a piece partly based on Remy Charlip’s “instructions from Paris.”11 And she improvised to music played live by her life partner, Richard Peck.

That concert earned her a compliment from Trisha Brown, who joined Grand Union around the same time Lewis did. Nancy recalled: “I used to be inhibited by her, because she knew that I wasn’t sophisticated about anything, really, and she put me down for it. [I was] a California hick plopping down in the middle of [New York City]. But after my performance … she came back and gave me a tight hug and said, ‘I know what you are doing and it’s good.’”12

Reviewing Lewis’s solo program during the 1975 Walker residency, Linda Shapiro wrote: “She projects a glamor which is both juicy and deadpan, a combination of Carol Burnett and Jill St. John.”13