GETTING INTO THE ACT: ARTISTS, CHILDREN, DOGS, CRITICS, AND HECKLERS

Who came to see Grand Union, and what was their experience? How did the makeup of the audience change over time and over geography? Did audience members ever participate—or was that out of bounds?

As I described in chapter 2 on SoHo, Grand Union sprang up in an environment of border-crashing artists. Being involved in their friends’ projects and seeing each other’s work were affirmations that there were new ways to do things. According to sculptor Richard Nonas, “[T]he only audience that any of us had for our work was the rest of us. So the dancers were the audience of the painters and sculptors, and the painters and sculptors were the audience of the dancers and the musicians…. Everybody was connected.”1 Some of the other artists in that milieu who came to see Grand Union were sculptor Richard Serra, composers Philip Glass and Gordon Mumma, actors/directors Ruth Maleczech and Joanne Akalaitis from Mabou Mines, Chilean pianist and artist Fernando Torm, and poet Ann Waldman.

The early performances sprawled through lofts and galleries with no theatrical lighting to separate watchers from doers. Knowing the dancers were improvising bestowed on us, the audience, a kind of alertness, a sense of high anticipation. Mary Overlie, who saw the group often, said a GU performance “was almost like a sporting event, some kind of heightened excitement that was kind of gladiator-like, just like hungry and excited out of your mind to watch what was going on there.”2 On the other hand, the GU style could be easily mockable—with affection. Terry O’Reilly, then and now a member of Mabou Mines, had the following memory of the theater group’s reaction after one GU performance: “We were rehearsing at Paula Cooper Gallery kind of goofing off, and Ruth [Maleczech] and Joanne [Akalaitis] did a send-up of the Grand Union. It was hilarious. Ruth was pushing a potted plant across the floor of the gallery in some kind of yoga slash dance squat locomotion. Joanne was doing a talking bit, and kind of skipping. Pretty good too.”3

∎

As mentioned, the SoHo denizens were not a racially diverse group. The people who came to see Grand Union in one loft or another were mostly young, white, and in the arts. But they were soaking up something different than audiences at other modern dance attractions. They didn’t come to see the latest work of a favorite choreographer like Paul Taylor or José Limón. The Grand Union audiences were more interested in how potential sparks would fly among the six or seven dancers. As Jared Bark said, “They would walk in wearing their street clothes, and you knew that within fifteen minutes something spectacular was going to happen.”4 As John Rockwell wrote in the New York Times, “People came back night after night, expecting and getting something new each time and following the permutations of the performers as if they were characters in an ongoing play.”5

∎

In the beginning, when Grand Union was still trying to incorporate the members’ choreography, it was pretty fluid as to who was dancing and who was watching. Seven-year-old Sarah Soffer, a neighbor of Yvonne’s, gamely joined a group formation at NYU’s Loeb Student Center.6 In January 1971, also at NYU, Jowitt reports that three small boys got into the act at the end; they belonged to Trisha (Adam), David (Ain), and Nancy (Miles).7

The following month, while Rainer was traveling in India, the group gave several loft performances that were casual, sparsely attended, and loose with respect to the performer/audience boundary. The Grand Union dancers were performing simultaneously with students who had learned David’s Sleep Walkers. In this version, called Wall Sleepers, Catterson recalls being given the option to leave the wall and join Grand Union proper. At another juncture, Steve asked for volunteers from the audience for an ad hoc piece. Catterson jotted down this description: “Stillness, little jumps, exits, interesting variations, herd closing in a huddle and then opening out with flailing arms and zooming across the space to really great music.”8 Trisha extended her hand to audience member Carmen Beuchat, the Chilean dancer she was working with, and off they went on a “walking and body-weight movement” duet. Catterson remembers one instance when a woman who was not invited behaved so strangely that she was worried for the woman’s sanity. On a happier occasion, a dog entered the space and Trisha, who loved dogs, danced a duet with it.

By 1972, people crowded into informal spaces like LoGiudice Gallery, paying a two-dollar admission fee (free if it was your second time). For most of the audience, it was understood by then that Grand Union was no longer asking for volunteers. Most of us wouldn’t step out of the audience to join them any sooner than we would walk onstage to play with Philip Glass’s ensemble. But occasionally a spectator interpreted their spontaneity as an invitation. Choreographer Risa Jaroslow recalled a time during this period when a woman from the audience sat in a chair in the performance area until Trisha whispered to her, then gently nudged her out of her seat.9

Trisha had her wits about her on another occasion, too. At The Kitchen in 1974, a dancer named Laleen Jayamanne had entered the fray the night before and was looking to repeat that opportunity. Baker wrote: “Trisha looked at Laleen coolly and said, ‘Maybe you could get a group of your own together and call it the A & P.’ The audience laughed loud, breaking the ice, and Laleen went back to her seat.”10

Then there was the time the Grand Union dancers capitulated to a group of charming interlopers. Robb Baker described it in Dance Magazine:

At Pratt, five little black kids decided they wanted in on the fun. Trisha put on a wig and hat and tried to scare them back into non-participation. It didn’t work. David Gordon, the most theatrical Union member, seemed the most disturbed by the outside threat. Doug Dunn and Steve Paxton more or less ignored the heckling, but Nancy Lewis and Barbara Dilley kept giving the kids sly little smiles as if they almost welcomed the intrusion.

At the end, the kids took over, rolling oranges, exhibiting their yoyo expertise, funky-chickening it up to the record-player soul of “bright, bright sunshiney [sic] day.” The Union members sat on the sides and watched, having changed places with their challengers. The reversal happened so quietly and naturally that it seemed almost a part of the show.11

These examples of audience participation by chance are not related to the Happenings of Allan Kaprow or the community events of Anna Halprin. For both Kaprow and Halprin, the bridging of the performer/audience divide was intentional. With Grand Union, that dividing line just happened to dissolve at times. The dancers’ intent was to give a performance for an audience, engaging their attention but not their dancing. As theater theorist Michael Kirby noted, however, the context made people feel they had been invited. He says that “they, the spectators, tend[ed] to project themselves,” thinking they could do it too, as no obvious technique was needed.12 As early as spring of 1971, Grand Union announced that the audience was not to take part.13

∎

The SoHo crowd was already part of the “tribe,” to use Barbara’s word—the tribe that kept coming back. But in other cities, it took some work for Grand Union to earn the audience’s trust. Minneapolis critic Allen Robertson seemed to understand the intensity of that trust: “The union isn’t just between the performers on stage; it’s also a bond with the audience. Without our willingness to go along with them, to take some of the same chances that the dancers on stage are taking, this particular Union would be little more than … meaningless, unorganized antics. We must dare to trust them and take the chance that our trust may go unrewarded.”14

In venues where there was less preperformance contact, the audience was less involved. (This tends to be the case with any dance company on tour.) Sometimes audience members were clueless about what they had signed up for. According to Grand Union’s tech director Bruce Hoover, the people who got dressed up in suits and ties to see “a dance concert” were so appalled by GU’s antics that they would sometimes get up and leave.15

Then there were times when the audience had to stay until the end. For the GU performance at the University of Montana at Missoula, it was compulsory for both the dance students and drama students to attend, and the drama students were not happy about this.16 Toward the end of a long, slow-moving concert in which Grand Unioners took turns filming with a video camera, Barbara was standing among the audience, aiming the camera toward the stage. As she was explaining something, a loud male voice from the audience behind her yelled “Bullshit!”

Apparently that one heckler was not done complaining. In the video, during the final applause, boos from the audience are also audible. Bruce Hoover’s description of the same performance was this: “[T]here was shouting from the audience. Somebody was really angry, and he came backstage after the performance. I think he was a little drunk. He sought out Steve and just started railing at him. ‘How dare you all do this? How dare you do this kind of thing? This is just disgraceful that you are doing this on the stage.’ Steve really handled it brilliantly. His calm and his peace [were] able to deflect that kind of energy.”17

Nancy remembers that Steve was eating a grapefruit right after the performance (Douglas had been peeling a grapefruit during the performance) when some of the audience came up onstage, and one young man, said, “You get paid for this!?” (Maybe if Steve had told him how little they got paid, the guy would’ve calmed down.) He may have offered the man a piece of grapefruit, which could be what Hoover described as deflecting the aggressive energy.18

∎

Critics agreed that being in the audience of Grand Union was a different experience than being at other dance concerts. Robb Baker said that the nature of the work was so private that he felt he was “eavesdropping” in the same fashion one does while watching a soap opera.19 Elizabeth Kendall felt the audience served as a witness, “an innocent bystander…. What was happening was so much ‘inside’ that group of people.” But audiences had different reactions to that insider feeling. Whereas Baker enjoyed the intimacy of it, Kendall felt vaguely taken advantage of, as though the group hadn’t worked hard enough to produce a real performance.20

The term “self-indulgent” was flung at Grand Union many times. Jowitt has deconstructed the term, calling it “a critic-ese expression usually meaning that the performers explored an event for longer than you wanted to watch them explore it.”21

My own feeling is that it’s simply a matter of trust—an almost visceral sense on the part of the critic about whether a given artist is believable. And if critics don’t feel an immediate sense of trust, or connection, they try to locate their distaste in some artistic error. For instance, Nancy Goldner, in a long review in the Nation, described Grand Union’s ability to improvise with great eloquence but then called much of the group’s dialogue “unbearably fey.”22

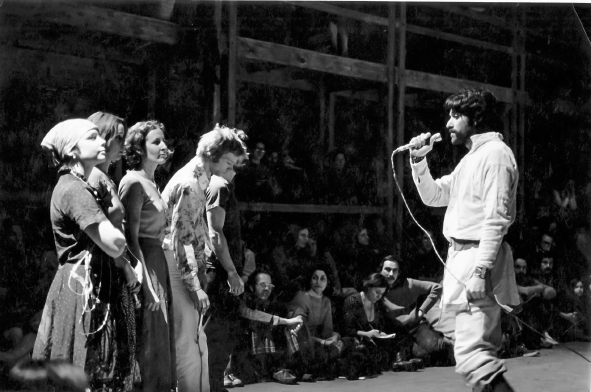

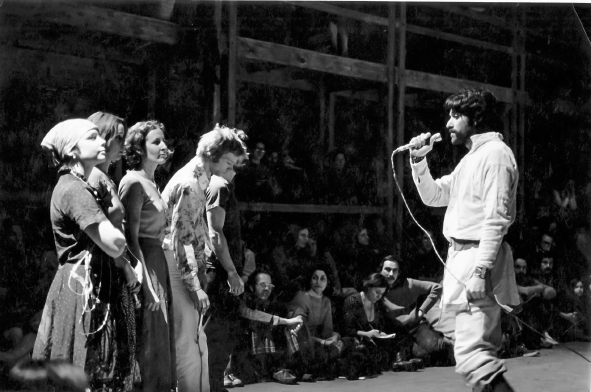

GU at La MaMa, 1975. From left: Dilley, Lewis, Brown, Dunn, Paxton (hidden), Gordon with mic. Photo: Gerald Gersh, personal collection of Douglas Dunn.

And critics who liked Grand Union sometimes expressed a wish to see the performers in a less theatrical setting. Arthur Sainer, a Village Voice theater critic, said he’d rather see them in a workshop situation where they would be under less pressure to make something happen, and where the audience would be more participatory and less adoring.23

During a meeting of Grand Union and invited critics (a gripe session, really, which I referred to briefly in chapter 14), critics differed on the challenges of reviewing the group. Robb Baker of Dance Magazine offered, “Sometimes I feel a new art form deserves a new writing form. One might write about improvisational dancing with improvisational writing, but I don’t know what improvisational writing is.” Art critic John Howell, on the same occasion, described the openness as a chore: “Since there is no formal framework, no manifesto, no method, other than the fact that you are going to appear in the space together, the writer has an enormous burden. I tried straight description, once—ridiculous. It could have been a book by itself and it didn’t say that much…. [The audience has] to deal with the openness of the situation.24

Maybe it’s only other artists, people who know what it’s like to face the blank canvas, who can appreciate the skill it takes to grapple with a whole evening of improvisation. The dancer/choreographer/writer Deborah Jowitt wrote this about the 1976 La MaMa performance: “[W]hat I appreciate most about the improvised evenings is being able to see the processes that either instigate change or block it. I’m not sure how to make this sound interesting to anyone else, but it means a great deal to me to watch performers making up their minds. Grand Union members occasionally embark on crazily risky projects, but I think they risk the most in being willing to show themselves at a loss. Between peaks. High and dry.”25

∎

Barbara Dilley saw how subjective every audience perceiver was and also how the vibes between performer and audience helped create a community.

[P]eople witness us through their own eyes and through their own experience. And they interpret it. But it’s not necessarily our reality. It is what we’re projecting. And it works as theater because it’s broad enough to be witnessed in a lot of different ways. But man, I hear that feedback coming in and everybody’s seeing it a little differently. The vistas are just broad enough … that if you are honest and genuine with one very simple thing, it can be mythic to anybody. I mean, you can become everyone sort of, a little bit. That’s the most ancient aspect of performance. You really surrender yourself to that. Because the audience, when they begin to feel that happening, they’re giving you the roles to play…. And in the Grand Union performances where this occurs—it doesn’t happen in all of them—there’s the distinct feeling that we are making choices to represent certain energies or certain personalities or certain characters because the audience is responding . So you yield to that energy…. [T]he implications are coming to us through the vibrations of the people watching.26

The people who were affected by Grand Union were affected deeply. We felt we were learning life lessons, lessons in how to be oneself while also swimming in the same waters with others. We were learning about flow from a collective guru, with no single person in the lead, and that itself was a kind of utopia.

Jowitt articulated why some of us felt so connected, so involved. She followed “the shifts of equilibrium, the spurts of directed tension, the changes of focus that we’re all constantly engaged in—alone or in groups.” She identified with “the way they all help each other out of difficulties or lend their weight to accomplish some group purpose…. [T]hey make us feel that we’re all locked into this (this what?) together; we have as much at stake as they do in the turn of events.”27

This is the kind of connection that Barbara felt from the other side, the performing side. In 1973 she said, “Some people learn a lot about behavior by seeing Grand Union more than once. They empathize with our dilemma, identify with our choices. We become both personal and archetypal figures to them.”28

MUSINGS ON NOTHINGNESS

When we go to see a performance, we don’t want to see nothing. We want to see something. But we sometimes forget that something comes out of nothing.

Critics often attacked Grand Union as boring, self-indulgent, nothing happening. They came to see a finished product. It didn’t make a difference to some of them that they were watching people create on the spot. Even Minneapolis critic Allen Robertson, who knew that watching improvisation requires patience, seemed offended by being exposed to the process of working things out. After seeing both performances during the 1975 residency at Walker Art Center, he wrote a long, insightful, seemingly understanding review. He was upfront about preferring to see Grand Union dance rather than talk. And then, after describing a lovely trio by Dilley, Dunn, and Lewis, he said, “Less than five minutes later, the evening has become a meaningless, unfocused shambles of nothings.”1

Each viewer sees things differently, of course. To my eyes, watching that performance on video, the “lovely trio” had been a mere holding pattern, and what came later yielded some amazing work between David and Nancy, a riddle-like duet between David and Steve, and vigorous experimentation between Steve and Douglas. Not to mention some beautiful night-time elegies involving Barbara. (See chapter 20.)

In any case, Grand Union members were used to being on the receiving end of this kind of diatribe. Back in 1966, when Yvonne Rainer premiered The Mind Is a Muscle, Part I, which was performed by Rainer, Paxton, and Gordon and later renamed Trio A, Clive Barnes wrote this in the New York Times:

Total disaster struck Judson Church in Washington Square last night. Correction: Total nothingness struck the Judson Church in Washington Square last night, struck it with the squelchy ignominy of a tomato against a pointless target….

The most interesting event of the evening was when someone, through the long extent of a blissfully boring dance number, threw from the top of the church a succession of wooden laths. Plomp, plomp went the laths and for a time, as these in rigid succession floated earthwards, one had a visual sense of something happening.2

Nothingness, of course, is in the eye of the beholder. If you are looking for a particular something and you don’t find it, you see only nothing. If you are looking for “meaning” and you don’t find it, what you see registers as meaningless. The “blissfully boring dance number” was Rainer’s Trio A, which is now considered an iconic work of postmodern dance. It is filled with difficult coordinations and a disjointedness that challenges the dancers to make a continuity. The phrasing is not musical, and the actions are uninflected, so it is basically antidynamic. Built into the choreography is an avoidance of meeting the eyes of the audience, so it is anticommunal. If you are looking for dynamics or if you are looking for a lovely performer/audience connection, you won’t find it here. You will find “nothing.” There is actually a lot of something in Trio A that brings up interesting questions: What is performance if the performer and audience do not “connect”? Is the performer an art object? What is phrasing if it’s not musical? What is the overall structure if the phrases are not repeated? Can we redefine organic?

What follows are random thoughts on nothing and nothingness, from my cullings and mullings.

∎

In 1957, Paul Taylor stood still while Toby Glanternik sat still for the entire four minutes during Taylor’s piece Duet. The music was a score of silence by John Cage. Taylor described this dance as “nothingness taken to its ultimate.”3 It was part of his concert of seven dances, several others also being minimal, at the 92nd Street Y. Louis Horst’s review in the Dance Observer contained no words; it was, famously, a blank space of about four inches by four inches. But Doris Hering saw something more than an empty space in this show. Writing in Dance Magazine, she called the concert “an effort to find the ‘still point’ in his approach to movement.” And for her, it brought up the question, “Does nothing lead to something?”4

∎

In Grand Union, nothing often led to something. Granted, there were times when “nothing” just stayed steady at a low plateau. One critic of Grand Union cited low energy, saying that the dancers didn’t even try to connect. Could that critic have interpreted patience as low energy? I think it’s fascinating to see how things play out when the dancers don’t force it but just allow things to happen.

∎

Mary Overlie: “Here is how, based on my observations, to begin building an awareness of the performer’s more expanded self, eventually leading to a greater command of presence. First, have the performer sit in front of a class, with nothing to perform, and collect data about themselves as they consciously allow themselves to be watched.”5

∎

Robert Dunn, describing his approach to teaching the composition classes that led to Judson Dance Theater, wrote: “From Heidegger, Sartre, Far Eastern Buddhism, and Taoism, in some personal amalgam, I had the notion in teaching of making a ‘clearing,’ a sort of ‘space of nothing,’ in which things could appear and grow in their own nature. Before each class, I made the attempt to attain this state of mind.”6

∎

Charles Mingus: “You can’t improvise on nothing, man.”7

∎

Could what appears to be nothingness be instead a case of incubation? This is from Oliver Sacks: “Creativity involves not only years of conscious preparation and training but unconscious preparation as well. This incubation period is essential to allow the subconscious assimilation and incorporation of one’s influences and sources, to reorganize and synthesize them into something of one’s own…. The essential element in these realms of retaining and appropriating versus assimilating and incorporating is one of depth, of meaning, of active and personal involvement.”8

I once heard Oliver Sacks speak about creativity at a conference of the Association of Performing Arts Professionals. While he was emphasizing the importance of a latent period away from the desk or away from the studio, he was speaking in a start-stop rhythm. He would say a couple sentences, then be silent for a few seconds and wait. Or think. Or incubate. Or nothing. His speech pattern was a stutter in slow motion. (He was known to be a stutterer, but it was striking to me how much his rhythm illustrated his point.)

Improvisation is similar but on a different schedule. It falls into lulls, in which dancers may not be connecting on a conscious plane. It may look or feel like nothing is happening, but that doesn’t mean the brain or body is blank. Maybe people who come to see improvisation in performance should adjust their expectations. Maybe they should be willing to sit through nothing before being swept away by something. And maybe what looks like nothing to him looks like something to her.

∎

“In one Dunn workshop experiment, Paulus Berensohn (one of the first five students in Dunn’s class) punctuated a solo with long periods of stillness, claiming that the dance’s ‘climax’ was the longest period in which nothing at all happened.”9

∎

David Gordon, on renting a studio in the early seventies: “I went there and I went there and I went there and I didn’t make any art. I began to try to make a dance, a painting, or something. I take a great deal of time to open everything up—the studio had cast-iron shutters—and a great deal of time to close everything up, and in between I can’t think what I’m doing here. I was walking in circles, stopping, and trying to think of some dancing to do and putting my hands in my pockets and changing my focus and starting again. I do that for weeks and weeks and one day, I said, Maybe this is the dance. What is it you’re doing? How many steps was that? Where do you look when you stop? I began to teach myself the thing I was doing that I thought was nothing because I didn’t have any something. That became the piece I called Oh, Yes.”10

∎

Douglas Dunn: “Early 70s—Only nothing can contain everything; only stillness embrace all movement; only simplicity all complexity and extremity.”11

∎

Nancy Stark Smith: “Where you are when you don’t know where you are is one of the most precious spots offered by improvisation. It is a place from which more directions are possible than anywhere else. I call this place the Gap. The more I improvise, the more I’m convinced that it’s through the medium of these gaps—this momentary suspension of reference point—that comes the unexpected and much sought after ‘original’ material. It’s ‘original’ because its origin is the current moment and because it comes from outside our usual frame of reference.”12

∎

According to Robert Dunn, Paxton’s dances were “the most anxiety-provoking” of all the choreographers at Judson. “They were wide open and unencompassable There was nothing very much to grasp onto. You just had to undergo them.”13

∎

Marianne Preger-Simon, about dancing in Merce Cunningham’s Spring-weather and People (1955): “[A]t one point in the dance, a group of four of us stood in one place and position for what seemed like fifteen minutes, though it was actually a much shorter time. We weren’t doing nothing—we were standing still. It was not a time to relax and rest, but more like a bird stopping in midflight on the tip of a branch, before taking off again.”14

∎

Douglas Dunn on Grand Union: “I recall a shtick several of us were trying: when ‘nothing’ was going on at rehearsal, you say, ‘Stop: now repeat whatever you were doing during the last thirty seconds.’ And then that memory of unpremeditated moves would become set as a bit.”15

∎

This excerpt is from John Cage’s “Lecture on Nothing,” originally printed in 1959. It appears in his first collection, Silence, on pages divided into forty-eight units, each with forty-eight “measures.” In the interests of economy, I am not replicating the original spacing here.

I have nothing to say and I am saying it and that is poetry as I need it…. Slowly as the talk goes on, slowly, we have the feeling we are getting nowhere. That is a pleasure which will continue. If we are irritated, it is not a pleasure. Nothing is not a pleasure if one is irritated, but suddenly, it is a pleasure, and then more and more it is not irritating (and then more and more and slowly). Originally we were nowhere; and now, again, we are having the pleasure of being slowly nowhere. If anybody is sleepy, let him go to sleep.16