Throughout Chris Ware’s oeuvre, the role of the superhero in contemporary comics remains a constant concern. Popular discourse tends to construe superheroes as the forefathers of all new comics texts, a belief that clearly troubles Ware. His work sometimes seems to toy with the possibility of effacing the superhero outright, whether through symbolic murders or spectacles of debasement. Ware’s novel Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth approaches the problem in a subtler way, establishing a parodic connection between the figure of the superhero and the eponymous protagonist’s long-absent father. This parallelism enables Ware to stage the ambiguities inherent in his work’s relationship to its own supposed paternity. A psychoanalytic investigation of the way fatherhood is represented throughout the novel reveals the sometimes oppressive pressure superheroes seem to put on the comics medium as a whole. Ultimately, it also allows Ware to explore alternative genealogies, looking beyond the absolute primacy of the father and rendering ambivalent his work’s relationship with the putative influence of the superhero. Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan thus imagines the space between personal and familial history as the ground for new comic historiographies.

The difficulty is that these new historiographies must come to terms with the relative intractability of the earlier versions of themselves they contest. Ware’s published comments suggest that while he acknowledges the role superheroes play in his work, he is critical of the way these figures characterize perceptions of his chosen medium. In the introduction to the volume of McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern that he edited, Ware notes, “Comics are the only art form that many ‘normal’ people still arrive at expecting a specific emotional reaction (laughter) or a specific content (superheroes).”1 Though the universal validity of this claim is increasingly dubious (due in part to the attention paid to graphic novelists such as Art Spiegelman, Ware, and others), it is undoubtedly the case that the ghosts of these prejudices continue to haunt the popular reception of contemporary comics. The title of Dave Eggers’s New York Times review of Jimmy Corrigan—“After Wham! Pow! Shazam!”—testifies to this fact.2 Any progress that comics make toward critical acceptance is cast as a turn away from the superhero, a movement that is seemingly never complete and that informs the reception of each new graphic narrative.

This Sisyphean impasse finds a striking analogue in what might be described as the frozen temporality of many superhero narratives. Umberto Eco has characterized this timeless state as the “oneiric climate” of the superhero, a kind of storytelling in which “what has happened before and what has happened after appear extremely hazy.”3 Despite their seventy-odd years of ostensibly continuous narrative history, characters like Superman and Batman never age and always eventually return to a kind of fundamental narrative stasis no matter what happens in a given story. Even as the larger narrative contexts of these characters have gradually transformed, this framework allows them to maintain the illusion of fixity. Histories of change, development, and evolution are thereby suppressed, contributing to the image of the superhero genre—and its readers—as trapped in a perpetual adolescence.4

Ware’s important early text “Thrilling Adventure Stories/I Guess,” first published for RAW in 1991, evidences a simmering irritation with such perceptions (see plate 2). Setting word against image, “Thrilling Adventure Stories/I Guess” superimposes a reflection on the narrator’s mundane childhood experiences over the images of a superheroic action story.5 Noting that the narrator speaks of a youthful passion for superheroes, Gene Kannenberg Jr. suggests that the story is ultimately about the boy’s inability to subsume the subtleties of real experience under the categories of his fantasy life.6 At the same time, “Thrilling Adventure Stories / I Guess” is also a metadiscursive lament on the reading public’s tendency to associate all comics with a single genre. Here, a realistic confessional narrative is subsumed into the image repertoire of the superhero, its beats and revelations co-opted in the service of a wholly different tale. At the level of the visual, the narrator’s recollections are effectively boiled down to the point where only his childhood reading habits remain in view. In this text Ware toys not merely with his work’s understanding of itself, but also with how it is received. His apparent fear is that readers will see his work as an extension of superhero narrative, irrespective of its actual content.

A frustration with this persistent misrecognition is staged with similar ire on the back of the paperback edition of Jimmy Corrigan. In lieu of an explanatory blurb, Ware offers a twenty-three-panel narrative in his spare style, describing the journeys of the putative “Copy # 58,463” of the very book that the potential reader holds. After being printed in China, the book is taken—first by boat and then by truck—to a “Barnes Ignoble Superstore” in the United States. When a clerk in the store attempts to file the book under W in the literature section, after traversing Tolstoy, Updike, and Vonnegut, a mustachioed older man snatches it from his hands. Expressing a sentiment Ware seemingly holds to be disgracefully universal, the manager remarks, “Look! . . . This is a ‘graphic novel’ . . . graffik nohvel . . . it’s kid’s lit . . . you know— superhero stuff . . . for retards!”7 There is a degree of cheekiness to this sequence, especially when one comes to the end and finds that the entire business has been set up as a parody of ads encouraging the “adoption” of third world children. Likewise, a circular stamp noting that Jimmy Corrigan was the winner of both the American Book Award and the 2001 Guardian First Book Prize serves as a smirking reminder that this text has earned respect in spite of its form. Further, this stamp presents an ironic twist on the Comics Code Authority’s “Seal of Approval” that once graced the covers of virtually every mainstream comic book.8 On the one hand, it suggests how far comics have come since the Comics Code Authority’s effective dissolution, while, on the other hand, it serves as a pointed reminder of the lengths the medium must go to validate itself if it is to be acceptable to a wider audience.

The anxieties expressed in this scene are very real. First, the manager’s painful, deliberate pronunciation of the term “graphic novel” suggests that this term, one engineered to disentangle the medium’s more “respectable” offerings from their supposedly vulgar origins, fools no one. Indeed, one need only look to the graphic novel section of a real Barnes and Noble to find that offerings by superhero publishers DC and Marvel Comics dwarf works like Ware’s in availability. Second, the juxtaposition of the graphic novel to the superhero genre produces a bridge between them that construes both as synecdoches of a larger climate of juvenility. According to this logic, comics have not matured and perhaps never will. Moreover, the manager’s address to the clerk contains a guarded threat, suggesting that anyone who tries to distinguish between the form and its most prominent genre is also “retarded.” The preponderance of articles proclaiming “Comics Grow Up!” continually reinscribes this perception, even as the articles themselves claim to refute it.9 What such titles suggest is that even as the medium “grows up,” it remains haunted by both its own childishness and that of its audience. Indeed, the phrase itself can easily be misread, taken as an imperative along the lines of, “Hey, comics! Grow up already!” rather than as a constative claim that “Comics have grown up.” Some, like Douglas Wolk, suggest that we avoid the problem altogether by simply speaking as though the medium has matured, even as we seek to complicate the belief that it was ever wholly childish to begin with.10 Others have attempted to turn the problem on its head, treating the connotation of juvenility as a resource.11 For Ware, however, no easy circumventions of the problem are forthcoming, necessitating a search for alternative solutions that is enacted on virtually every page of Jimmy Corrigan.

The first way out of the perception that comics are a fundamentally infantile medium is the symbolic death of the superhero. Early in Jimmy Corrigan, the novel’s eponymous protagonist spots a caped man dressed in the costume of a superhero on a ledge across from his cubicle. The two wave to one another, and then the latter jumps, landing facedown on the sidewalk below. At first a crowd gathers around the body, but they eventually depart, leaving the colorful corpse to rest alone on the otherwise dreary street (14–16). Among those who briefly linger by the body is a man carrying what appears to be two large art portfolios, perhaps a stand-in for the cartoonist himself. It is tempting to read this figure’s passing interest as indicative of the attitude the book as a whole will take toward the superhero—the brief acknowledgment of a dead form. The idea here is that, given time, the genre will kill itself off, becoming nothing more than an object of obscure interest.

However, the corpse is a mere allegorical counterfeit, a substitute by which the novel sacrifices the superhero in effigy. Pages after the initial incident, Jimmy notices a newspaper that describes the accident. Its headline begins, “‘Super-Man’ Leaps to Death,” a promising alternative to the claims of newfound maturity cited above. Yet the paper continues, “Mystery Man Without Identification Falls Six Stories in Colored Pantaloons; Mask / Definitely not the Television Actor, Authorities Say” (30).12 Thus, even within the narrative, the effacement of the superhero is doubly a failure. Not only is it not the real thing, it is not even the actor—a man who has, as we will see, already played a central part in the narrative—who stands in the place of the real thing. Sending the doppelgänger to his death thereby reveals itself as ineffectual mockery. Joseph Litvak observes, “Mocking, as the term suggests, involves both derision and mimicry, or involves derision in mimicry.”13 Here, the inability of the “authorities” to identify the body entails a failure to properly imitate the original, arguably voiding any attempt to debase it. In positioning itself as the witness to the superhero’s suicide, the novel succeeds most clearly at unveiling its own reluctant fascination with the figure it ostensibly opposes.

With this in mind, one notes the way that both Jimmy’s gaze and the narrative’s attention linger over the body, even after it has been abandoned by others, staying with it until an ambulance arrives to remove the remains (17). There is an air of eternity to this moment of captivation, the absence of any lexical indicator of time’s passage leaving the sequence’s temporal flow ambiguous.14 Further, at several points, the window out of which Jimmy looks functions as a second frame within the frames that make up the page. Generally speaking, the division of panels is the most basic unit of time’s passage in comics, meaning that these frames within frames engender the segmentation of time unto itself, indefinitely prolonging each moment. Time is not arrested here—arrows clearly indicate the movement from one panel to the next—but its pace and the reader’s place in it are rendered uncertain. Together, these factors leave both Jimmy and the counterfeit superheroic corpse he contemplates suspended in the oneiric climate of the superhero. As Eco notes, most real change in superhero comics risks being revealed as the product of fancy or dream.15 It is the stable body of the superhero that fascinates here, while its death is like some imaginary tale or “What If?” scenario, a reverie from which this narrative must eventually awaken. Like Jimmy, the novel cannot quite bring itself to look away, entrapped as it is in this timeless temporality. What Jimmy Corrigan must find, then, is not a new instrument of assassination, the bursting shell that will at last pierce the superhero’s skin, but a new way of seeing.

Such a fresh perspective might well be found in parody. Judith Butler has argued that efforts at parody take root in the parodist’s identification with his or her object. The point is ultimately a simple one: to parody something, one must be able to stage one’s relation to it, but this relation must itself be staged in such a way as to leave the precise nature of the connection uncertain.16 Parody might thus be understood not as a mere spectacle of denigration, but as a process of disruption. Its power derives from its ability to unsettle regimes of correspondence and non-correspondence, similitude and difference. Butler’s formulation provides a tidy summation of the ambiguities at work in Jimmy Corrigan’s reconsideration of the superhero, a reconsideration organized, as we will see, around the ambiguous connection between the figure of the superhero and Jimmy’s father. This is a practice that promises to implicate Jimmy Corrigan within the discourse that it critiques, helping to make ambivalent the narrative’s relationship to the superhero.

In Jimmy Corrigan’s opening pages, the young protagonist attends an autograph-signing event held in honor of an actor known for playing Superman on television. When Jimmy’s mother arrives on the scene, the actor offers to take her out to dinner as soon as he gets “off work” (2). Later, the man goes home with the two and spends the night with Jimmy’s mother. This act of seduction establishes a foundational correspondence between the superhero and the father, even as it begins to disrupt the pristine image of conventional heroism. The actor becomes a bridge between the two figures, offering both a visible stand-in for Jimmy’s absent paternity and a tangible manifestation of his fantasy life. Supporting this association is the way the actor’s face appears, albeit masked, in full in a panel, as he remarks, “Hello, son” (2). He is one of only three characters not patrilineally related to Jimmy to be shown in this manner, a fact that literally draws him into the Corrigan genealogy. That he can be fully represented only so long as he remains masked implies that it is precisely his embodiment of a fantasy that allows him to emerge in the visual register of the text. Made anonymous, he becomes a template onto which Jimmy’s patrilineage will be projected. This effect has a disruptive consequence of its own, making it perpetually unclear whether it is the father who is the model for the superhero, or the superhero who is the model for the father.

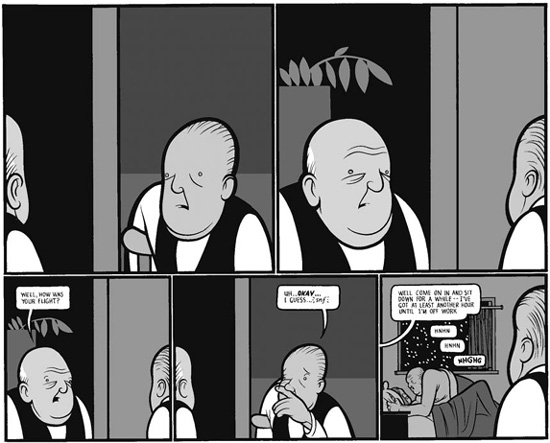

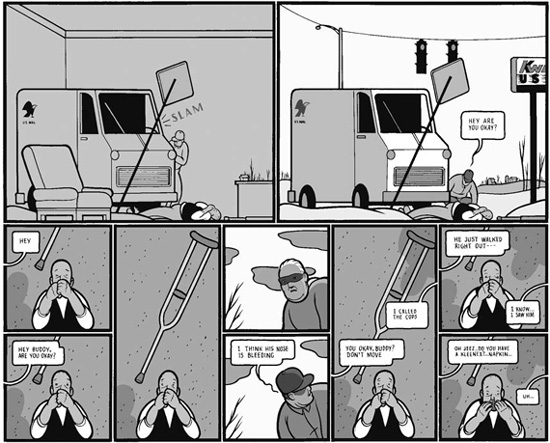

Throughout the novel that follows, associations between these two figures ping-pong back and forth. When Jimmy meets his long-absent father, for example, he is told to sit down until the elder Corrigan gets “off work,” explicitly echoing the actor’s initial attempt to proposition Jimmy’s mother (2, 36) (see fig. 2.1). Ware projects this remark over a presumably fantasized image of Jimmy looking on as his father has sex with an unknown woman who is almost certainly his mother. His father’s imaginary grunts are inscribed directly beneath this real remark, suggesting a crude double meaning to the suggestion he has yet to “[get] off work” and producing a degree of formal continuity between the father of fantasy and the father of fact.17 This super-imposition of word and image—not so unlike the formal strategy at work in the earlier “Thrilling Adventure Stories / I Guess”—has the further effect of retroactively portraying the Superman actor as the violent father of an over-determined primal scene. Seemingly triggered by the phrase “[get] off work,” the narrative’s descent through a series of placeholders and stand-ins into fantasy suggests that it was, figuratively speaking, Superman who first slept with Jimmy’s mother and Superman who has stood in the imaginary place of the father all along.18

Complicating matters is the fact that Jimmy’s own largely renounced sexuality is entangled in his identification with the superheroic father. Earlier, in the opening episode, Jimmy dons a handmade mask before a mirror, suggesting a fundamental identification with the superhero as the guarantor of his own self-image. In Jacques Lacan’s memorable phrase, this disguise becomes the “armor of an alienating identity,” the means by which the totality of his own body is made visible to him.19 That is, in the complete image of himself that a child sees in the mirror, his self-identity is constituted through a reflection that is never fully his own.20 Our concrete reflections are, in a sense, figures of our paternity, the person or persons that precede us and bring us into being. For Jimmy, this illusion of optics is literalized—he becomes whole by taking on the role of the character that holds the vacated position of his absent father. The narrative consequences of this identification become clearer the following morning, when the actor sneaks out before Jimmy’s mother wakes, hands Jimmy his own stage mask, and tells Jimmy to explain that he “had a real good time” (3). A few minutes later, Jimmy’s mother appears in the kitchen, only to be confronted by the spectacle of her now-masked son, who, in a panel that rhymes visually with the actor’s own early appearance, parrots the words he has been told to convey. The as-yet unrepresented primal scene is hereby prefigured as the confirmation of Jimmy’s self-identity. In the process, he simultaneously assumes the position of the superhero and his mother’s lover. If Jimmy’s imaginary self-image is doomed to failure, it is precisely because he can never fully embody this role, barred from filling it by the prohibitive structures of the incest taboo, structures that psychoanalytic thought equate with the father’s law. Simply put, Jimmy can never fully be the figure he emulates because to do so would involve initiating a forbidden relationship with his mother.21

Fig. 2.1. On their first meeting, Jimmy and his father mirror each other in a sequence that gives way to a fantasy of the primal scene. Chris Ware, Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth (New York: Pantheon, 2000), 36.

The paternal gift of self-identity thus comes at a price, the renunciation of Jimmy’s own desire. Throughout the novel, he is trapped in a sort of perpetual adolescence, able to satisfy his longings only through his masochistic fantasy life. This is a conceit that makes him a perfect double for the supposed readers of superhero comics, or, even, for the comics medium itself.22 One episode finds him recording the sounds that surround him as he sits in an urban park. He records first the song of a bird, then the passing of an airplane, and finally the brief conversation of a pair of lovers (94–96). The first two items serve as reminders of the famous mantra, “It’s a bird; it’s a plane; it’s Superman!” By connection, then, the boyfriend of the female speaker, a man she calls “the most wonderful guy I’ve ever met,” might be understood as the third member of this ecstatic sequence. Superheroes, the formulation goes, are those who are loved as well as those whose desire can be returned by another. For Jimmy, however, the identification with the superhero is always an identification with something that is itself other, something that guarantees the coherence of his own desires even as it presents them as perpetually distant from him.23 He has only the image of what it is to be a sexualized adult, but lacks the understanding of what it means to truly be grown up.

We can read Jimmy’s alienation from his sexuality, and perhaps his alienation in general, as an allegory of the status of comics. As Ware’s own remarks suggest, the prominence of the superhero genre in comics metonymically configures the medium of which it is a part as “kids lit [. . .] for retards” (back cover). Jimmy’s protracted adolescence would then stand in for the ongoing failure of the medium to grow up in the eyes of the larger reading public.24 This is not merely a problem of reception, but also of production. So long as it is the superhero that provides an experience of self-coherence, Jimmy cannot come to terms with desires that are his own. Comics, likewise, are effectively barred from becoming something other than what they ostensibly have been. This is a sort of “paternalistic pedagogy,” a mode that, as Eco puts it, “requires the hidden persuasion that the subject is not responsible for his past, nor master of his future.”25 Superheroes here function as the limit of the comics medium’s aspirational horizon, a point that they always approach, but can never surpass.

Thus, the superhero is a perverse Freudian father-of-enjoyment, that monster of the psyche that takes all pleasure for itself and offers none to its progeny. In Totem and Taboo, Sigmund Freud tells the story of the members of a primitive horde who are forbidden by their father to take any of the women of the tribe as their own. Frustrated, they eventually kill and eat the pater-familias.26 Once this act is complete, their ambivalence about their father, whose strength and power led them to love him, overwhelms them with guilt. This in turn prompts them to take the formerly external prohibitions of the father into themselves, producing a psycho-sexual code of renunciation that ironically reanimates the prohibitions they once struggled to overcome.27 One need not take this psychoanalytic myth at its word to acknowledge its explanatory force. The law of the father represents the internalized expression of our ambivalence toward those who shape us, the coupling of our admiration for what they offer with our irritation at that which they prohibit.

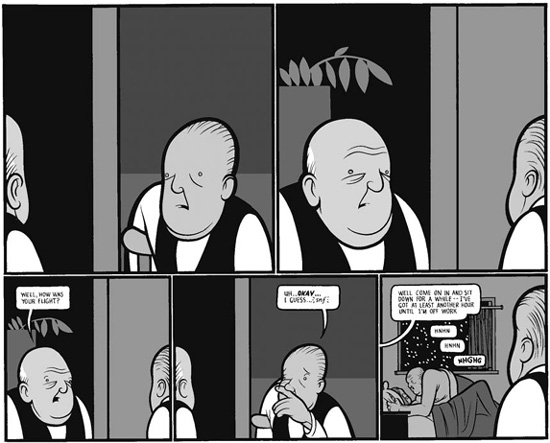

Fig. 2.2. Hit by a mail truck, Jimmy briefly imagines that the driver is an aged superhero. Chris Ware, Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth (New York: Pantheon, 2000), 97.

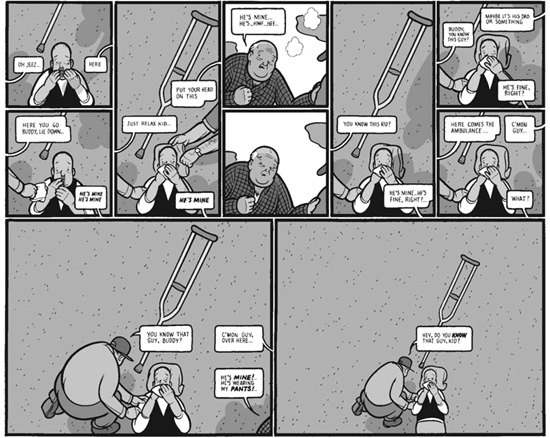

This ambivalence is very much at work in the way Jimmy Corrigan occasionally takes up the possibility of the superhero as savior or protector, exploring the projected image of an ideal father only to refute it. In an episode that comes roughly a quarter of the way through the book, Jimmy is hit by a mail truck and knocked to the ground (see fig. 2.2). For a single panel, the truck’s driver, seen from Jimmy’s supine perspective, is replaced by an image of the masked actor, his hair now white and his face rounded. On the following page—compositionally a nearly exact horizontal and vertical mirror of the first—the driver is pushed out of the frame by Jimmy’s father. Clearly out of breath, the older man huffs, “He’s mine . . . He’s . . . hmf . . . hff . . . .” (98) (see fig. 2.3). The moment is at first striking for the willingness of Jimmy’s father to claim the boy he abandoned, offering the possibility of reconciliation in and through crisis. This doubling suggests a more positive understanding of the here literal mirroring of the father and the superhero. Simultaneously, however, one might read something more sinister into the comparison. James’s inarticulate gasps hearken back to the grunts of Jimmy’s earlier fantasized primal scene. In this light, James’s insistent assertions of paternal ownership—“He’s mine! . . . He’s wearing my pants! . . .” (98)—can be understood as expressions of the father’s law. That is, they repeat the way that Jimmy’s acknowledgment of his paternity traps him in a structurally inferior position. The superhero is thereby configured not only as a salvific figure, but also as the signifier par excellence of filial restriction and constraint.

Fig. 2.3. Jimmy’s father lays claim to his son, taking the place of both superhero and driver. Chris Ware, Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth (New York: Pantheon, 2000), 98.

If so, one of the novel’s projects may be to undermine the force of this law through parodic iteration. Shortly after Jimmy’s initial encounter with his father, the elder Corrigan’s car is stolen, a fact that Jimmy meekly points out. As is often the case with such moments of catastrophe in the narrative, the immediate consequences of the theft do not play out on the page. Instead, the narrative diverges into one of Jimmy’s fantasies in which he speaks of the incident to an unseen child: “Scared? Ha ha . . . oh no I wasn’t scared. Because if I had been I never would have met your mother and then we would never have had you” (49). The theft of James’s car, an episode of real paternal impotence, thus opens the possibility of Jimmy’s own fantasized sexual potency, even as it points to the limited horizon of his own idea of maturity.28 In the process, it also puts him in the position of the father, his normally reticent speech replaced by a surprising loquacity. In assuming the role of the father, he has become, though in fantasy alone, the master of a discourse that once eluded him.

However, this project of fulfilling the superheroic father’s place is doomed to fail, undermined by its redeployment of the very logic it seeks to disrupt. Paternal power intervenes in Jimmy’s fantasy in the form of a tiny, portly Superman who appears at the window. This event derails Jimmy’s narration and inspires him to describe not what ostensibly happened, but what is happening, forcing him to shift from a “How I met your mother” story to an account of the man on the windowsill.29 With the loss of his discursive mastery, Jimmy’s fantasy spirals out of his control, and Superman grows massive, lifting the house and then tossing it back to the earth. Jimmy’s dream son is seen for the first time, his limbs scattered around the upended house. Here we learn that the now-fragmented child’s name is Billy, a telling fact given nearly every previous member of Jimmy’s patrilineage has been named James. Through Jimmy Corrigan’s expansive narrative, the familial circumstances of each of these men enclose them, such that the name they share increasingly comes to seem a prison. What this child represents, then, is the desire for a future that makes a radical break with the past, one that quickly descends into vaudevillian tragedy. To seek a new name is, up to a point, to seek a new law. Yet the conditions by which this law is authorized are precisely those of the prior law, allowing it to return with a vengeance, as the violent intrusion of the superhero suggests. Indeed, it is no accident that “Billy” is the diminutive of William, the name of Jimmy’s paternal great-grandfather. Even the seeming break Jimmy makes from his past therefore reinscribes an already-written narrative of parental authority. Here we must also recall Butler’s observation that insofar as parody begins in identification, it sometimes fails to engender a final disassociation. Unable to achieve true rupture, the successful parodist must work from inside that which is parodied.

Seemingly aware of this necessity, Ware finds a more productive strategy of resistance to the superheroic legacy through genealogy. Jimmy Corrigan’s investigation of the real complexities of family history finds its purest form in the book’s consideration of the giving of names. On two separate occasions, medical doctors refer to Jimmy as “Superman.” The first occurrence, coming after Jimmy’s accident with the mail truck, is all but unprompted. Largely forgettable in and of itself, the incident seems to be the product of little more than bedside banter.30 The second incident is more clearly occasioned by the Superman sweatshirt that Jimmy borrows from his father and wears after the latter’s own ultimately fatal car accident. In both cases, the pleasures of identification might be read as reparative acts. If Jimmy’s problem is one of alienation from his own image, this casual act of renaming offers him a new relation to himself. Jimmy, always an inferior and belated copy of the father’s ideal image, is invited to occupy the place of the too-perfect surrogate. The point is not that this rechristening sets him free, only that, as we will see, it helps ease the burden of family history. Where the act of naming has previously proceeded from father to son, these doctors suggest the possibility of a less linear structure of relation and inheritance.

Further layers of complexity are evident in the Superman sweatshirt that inspires the second naming. Though borrowed from Jimmy’s father, the shirt is actually a gift from his adopted daughter, Amy. Indeed, so too is the “#1 Dad” shirt that Jimmy uncomfortably appropriates earlier in the text, both of them Father’s Day gifts (343). This revelation serves as an important reminder that the appearance of superheroism—or, for that matter, paternity—is bestowed, not a given. Whatever powers the family’s symbolic structures of prohibition and control possess, they do not simply precede us. Thus, the force of the father—the mask he wears—is in part the gift of the child, his own empowered identity the product of various exchanges and relations between fathers and their progeny.

As we learn in one of the novel’s many investigations of Jimmy’s ancestry, Jimmy’s great-great-grandfather was also a doctor. Although this man does not appear in the novel aside from miniature panels in the book’s opening diagram, he effectively returns in the place of the two doctors with whom Jimmy interacts. Three generations of Jimmy’s ancestry are thereby elided as two wildly distant moments of family history are brought into contact with one another through a doubling that only the reader can recognize. The name “Superman” is evoked only to facilitate this exchange. Its central place in conventional understandings of the comics medium demonstrates the significance of this transaction, but the word itself has no real significance of its own. Superheroes, and the concerns Ware’s work expresses about them, can be understood as the ground on which farther-reaching historical inquiries are built. If superheroic fantasy is inescapable in comics—or the popular perception thereof—then fantasy itself must be turned to other ends.

A possible approach is evident late in the text when Amy leads Jimmy through a set of pictures from the familial past they never shared. As they are removed from the jumbled boxes that contain them, each photograph neatly fills a comics panel (323–26). These recovered moments are thereby brought into the passage of time in the present, their spatialization animating them in relation to both their presentation and contemplation. Amy’s boxes are thus proto-comics, pure formal potentiality always awaiting retemporalization by means of her selection and presentation of them. This reinsertion of the image into the stream of time is the past’s reincarnation, its rebirth in a new form through its contextualized reception. Significantly, three different registers are co-implicated here: first there is Amy’s productive present in which she tells a story through the juxtaposition and narration of images. Next is the past that is reanimated by it. Last is the future reception of the text, represented here by Jimmy’s largely mute responses to the images Amy shows him. Interestingly, Jimmy is implicitly figured as a reader of comics, noting at one point after a temporal ellipsis of indeterminate length, “But when I grew up I guess I sorta stopped reading them. [. . .] I-I wouldn’t r-really r-read them n-now . . . u-unless the art was good” (329).31 If Amy and Jimmy both bore each other here, it is because their distinct, almost accidental reflections on comics have the character of narrated dreams—important to their subjects as they are dull to everyone else. Strictly speaking, this sequence is not liberating for any of its participants. Instead, it points to the potential of comics to intervene in and rearticulate the very historical processes from which they emerge.

Amy’s plastic approach to family history suggests the possibility of breaking with the singular historiographic trajectory that the superhero tends to impose on comics, even if it can never fully leave the superhero behind. Jimmy Corrigan seems here to call for a more general form of genealogy that would account for the causal connections that stretch between various forms and figures rather than a simple genealogy of the superhero. Under the aegis of such an approach, the goal would not be to exclude the superhero, but to show what an excessive focus on it has already excluded. Formally speaking, Ware’s cartooning in Jimmy Corrigan works to model and redouble the complex genealogies toward which its plot aspires. Through the novel’s examination of the father, the superhero is shown to represent but a solitary point in time. Far from holding a single story in place, the work of genealogy—like the work of cartooning—can manipulate this seemingly singular node, putting it into new relations of meaning and constellations of causation. Jimmy’s father is a far different man when seen through Amy’s eyes than his equation with the superhero would suggest, less a potential tyrant than a benevolent co-parent. His inheritance of this other role is a product of the flexible attitude toward the past that Amy’s accidental cartooning enables. Time’s stable flow, Ware reminds us, is an illusion of the operations of closure by which we connect each moment to the next. What Ware offers, then, is less a precisely articulated solution to the problem of the superhero than a portrait of the superhero’s own endless entanglements.

The paradigmatic example of this technique’s potential is a two-page spread that appears near the text’s conclusion. Showing Amy alone in the hospital after her father’s death, the page suddenly opens up to reveal the process of her adoption. Then, in a series of short strips connected by arrows, time telescopes in a variety of directions, showing how Amy came to be where she is (see plates 9 and 10). This diagram’s purpose—if it can be reduced to one—is to reveal that Amy and Jimmy actually share a common ancestry. Her grandmother is the illegitimate child of Jimmy’s great-grandfather and his African American servant. In the process of revealing this information, the diagram opens the novel to moments otherwise lost to its multi-generational narrative: a flower pressed in the pages of a Bible, a plain grave in a military cemetery. These relics of the past can appear only through the folding of time that comics make possible, multiple passages turned into and over one another like sheets of origami paper, producing from them a wholly new shape that at once interrupts and celebrates the passage of time.32

Comics may not, in the final instance, be able to fully disassociate themselves from the legacy of the superhero. Indeed, though representations of superheroes and their stand-ins are all but absent from the book’s closing pages, Ware’s last image poignantly reiterates the rich ambivalence that has echoed throughout the narrative. Opposite the words “The End,” Ware shows, in miniature, a young Jimmy carried through the air by an aged Superman, snow falling all around them (379). For all its frustrations, the superhero returns here as a figure of relief, the very familiarity that makes it the medium’s curse providing a final comfort in the wake of the novel’s many un-recuperated losses. Perhaps the best comics can do is take advantage of their own formal resources, unveiling forgotten histories and mislaid things, until this consolation is no longer needed.

1. Chris Ware, “Introduction,” in McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern 13 (San Francisco: McSweeney’s, 2004), 11.

2. Dave Eggers, “After Wham! Pow! Shazam!” New York Times Book Review, November 26, 2000, 10–11.

3. Umberto Eco, “The Myth of Superman,” in The Role of the Reader, trans. Natalie Chilton (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1979), 114.

4. In a significant argument to the contrary, Geoff Klock has sought to make the case that superhero comics have grown increasingly self-reflexive over the course of the past three decades. This process of maturation is, Klock asserts, the result of their efforts to grapple with the influence of their generic forefathers. While Klock’s claims are more compelling than some of his critics are willing to acknowledge, Ware’s problem seems to be how to escape the perception of influence rather than influence as such. See Geoff Klock, How to Read Superhero Comics and Why (New York: Continuum, 2002).

5. Chris Ware, “Thrilling Adventure Stories / I Guess,” rpt. in Quimby the Mouse (Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2003), 39–41.

6. Gene Kannenberg Jr., “The Comics of Chris Ware: Text, Image, and Visual Narrative Strategies,” in The Language of Comics: Word and Image, ed. Robin Varnum and Christina T. Gibbons (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 183–86.

7. Chris Ware, Jimmy Corrigan (New York: Pantheon, 2000), back cover. All further references to this text will be indicated in parentheses.

8. Established by the Comics Magazine Association of America in 1954, the Comics Code Authority maintained a strict set of guidelines regulating “appropriate” content for comics publications. Distributors refused to circulate titles unless they featured the Authority’s “Seal of Approval” on their covers. For a condensed history of the Comics Code see Amy Kiste Nyberg, “Comic Book Censorship in the United States,” in Pulp Demons, ed. John A. Lent (Madison: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 1999), 42–68. For a more expansive account see David Hajdu, The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America (New York: Farrar, 2008).

9. An article in the Morning Call newspaper opens with just such a headline, noting, “Comics Grow Up . . . and So Do Their Readers.” Brian Callaway, “Comics Grow Up . . . and So Do Their Readers,” Allentown (PA) Morning Call, November 10, 2008, B6.

10. Douglas Wolk, Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo, 2007), 1.

11. Susan M. Squier, for example, has argued that comics might provide a resource for disability studies insofar as they “unsettle conventional notions of normalcy and disability.” See Susan M. Squier, “So Long as They Grow Out of It: Comics, the Discourse of Developmental Normalcy, and Disability,” Journal of the Medical Humanities 29.2 (2008): 71–88.

12. This headline is a reference to the death (and presumed suicide) of actor George Reeves on June 16, 1959. Reeves played Superman in the 1950s television series. Les Daniels, Superman: The Complete History (San Francisco: Chronicle, 1998), 97–99.

13. Joseph Litvak, Strange Gourmets (Durham: Duke University Press, 1997), 61 (Litvak’s italics).

14. I draw the term “lexia” from Gene Kannenberg Jr., who uses it to describe any linguistic element in a panel. See Kannenberg, “The Comics of Chris Ware,” 178.

15. Eco, “The Myth of Superman,” 114.

16. Judith Butler, “Merely Cultural,” Social Text 52/53 (1997): 266.

17. This panel, the fifth and last on the page, is also notable in that panels one and two and panels three and four mirror one another, demonstrating an uncanny resemblance between Jimmy and his father. Breaking this pattern, the fantasized sex scene implies that, despite the visual resemblance between the two men, something belongs to the father that is yet denied to the son (36). As Daniel Raeburn shows in his monograph on Chris Ware’s work, this doubling of father and son is repeated on the dust jacket of Jimmy Corrigan’s hardcover edition. When the jacket is properly folded, half of Jimmy’s face merges with that of his father. Daniel Raeburn, Chris Ware (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 69.

18. Importantly, the correspondence is, first and foremost, a formal one, arguably existing below the level of the naïve Jimmy’s fictional consciousness. Moreover, in this light, Jimmy’s vision of murdering his father on the following page might be understood as a futile attempt to re-contain the knowledge that here bubbles to the surface of the narrative through the conjunction of these two figures.

19. Jacques Lacan, “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the I Function as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience,” in Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: Norton, 2006), 78.

20. The mirror may be the most primal form of a panel sequence in comics, the passage of time at once staged and denied in our encounter with the reflective frame.

21. Jimmy’s fantasy of sex with Amy, his adopted sister (and, as we eventually learn, blood relation), arguably repeats this otherwise impermissible act in a more acceptable form (333).

22. It bears noting that for Eco sexual renunciation is a mark of the classic superhero’s oneiric condition. Eco, “The Myth of Superman,” 115.

23. In a telling slippage, Jimmy displaces any discontent with this superheroic/paternal stand-in onto the woman, muttering, “Ha ha Bitch,” as he replays his tape of her admission. Misogyny here rears its head as one consequence of the failure to come to terms with the superhero’s centrality (94).

24. Jimmy Corrigan as a whole is too capacious and complex for such an approach to be a total one. Accordingly, my account can only point to one of the many problems at work in the novel, not a fantastical solution to the novel as a whole.

25. Eco, “The Myth of Superman,” 117.

26. Sigmund Freud, Totem and Taboo, trans. James Strachey (New York: Norton, 1950), 175–76.

27. Ibid., 178.

28. From the start, the novel couples parental power and potency with the automobile, as it is at a car show that Jimmy and his mother meet the actor who plays Superman.

29. It bears noting that the tiny man at first resembles an action figure, suggesting that Jimmy’s dream of successfully realized adulthood is defeated by a recognition of the resemblance between this reverie and the submerged desire for maturity present in childhood play.

30. One might note the way the doctor links Jimmy’s mysteriously injured foot to the superheroic mythos, asking, “How’d you do this one—leaping tall buildings in a single bound again?” (128). Jimmy’s bound foot offers a reminder of Oedipus’s punctured feet and establishes a further connection between barred superheroic desire and the Oedipal constellation.

31. On the dust jacket of Jimmy Corrigan’s hardcover edition, Ware shows that Jimmy is still a collector of comics, indicating his claim that he no longer reads comics is likely a product of his embarrassment (dust jacket).

32. Jimmy Corrigan’s hardcover dust jacket literalizes this practice, at once unveiling further complexities to Jimmy’s genealogical descent and making them disappear into the folds of the paper itself (dust jacket).