In the ruins of great buildings the idea of the plan speaks more impressively than in lesser buildings, however well preserved.

—Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama

In a two-page sequence of Chris Ware’s “Building Stories,” architecture both evidences and withstands the passage of time.1 Both pages depict the same Chicago apartment building in pale yellow morning light, one in the early, the other in the late twentieth century. On the first page, the apartment building has decorative molding around its roof and curtained windows (see plate 11). A horse-drawn wagon carrying milk passes underneath the first-floor bedroom window. Ware narrates the scene in cursive lettering: “A young boy, fingers idly wandering beneath his quilt, dreams of the future, and how he might win the heart—and the body—of the girl downstairs” (23). The lettering complements the content; cursive lends the narrative voice intimacy and sentimentality, as if these omniscient remarks could also be found in a diary, carefully scripted by hand. Above this text, there is a series of inset circular panels which depict the boy’s fantasy romance; he becomes a pilot, flies around the world, writes “I love you” in the sky, marries his downstairs neighbor, then takes her upstairs to his childhood bedroom, still decorated with a model biplane hanging from the ceiling by a hook. In the lower portion of the page, Ware focuses on the object of the boy’s fantasy: “Meanwhile, this same girl is awakened by the jostling of closely-packed milk bottles, a gentle sound she’s loved all her life” (23). Ware endows the scene with nostalgia for this earlier industrial era, constituted by horse-drawn milk carts and heroic biplane aviation. The characters are comforted by their turn-of-the-century urban surroundings and fantasize about the future.

The next page takes place in late twentieth-century Chicago, and the building has been stripped of its roof ornament and curtains (see plate 12). Ware again narrates his characters’ fantasies: “The same morning, many decades later: A young woman, her mind gone idle over the overwhelming reality of her loneliness, muses as to the original use of a hook, worming its way out of the ceiling directly above her head” (25). The “young woman” is the female protagonist of “Building Stories,” an employee of a local flower shop who has a prosthetic leg. In a series of inset panels, she imagines the hook supporting a curtain dividing the bedroom, a hanging planter, a clothesline, and finally a toy spaceship in a boy’s bedroom, the closest match to the previous image of the boy’s model biplane. On the street level, a blue two-door car has replaced the horse-drawn carriage, and the girl who lived on the first floor, now an elderly landlady, lies in bed imagining, in another inset panel, that the “klinktink of a bottle, smashing on the pavement below” is the sound of the previous panel’s milkman (25). In the earlier page, fantasy life grapples with the future, and the present is comforting. In the contemporary setting, however, Ware’s characters only meditate on the past. “Building Stories” contrasts the possibilities embedded within architectural space in the early twentieth century with the archival fantasies about the same space that provide comfort in late twentieth-century America.

Ware’s interest in architecture is further developed in Lost Buildings, an “on-stage radio & picture collaboration” with National Public Radio host Ira Glass.2 Lost Buildings is about Tim Samuelson, the Cultural Historian of the City of Chicago, his mentor, the photographer and urban preservationist Richard Nickel, and their love of Louis Sullivan’s turn-of-the-century American architecture. The work was originally performed as a slideshow, combining Ware’s drawings, Ira Glass’s interview with Samuelson, and a musical soundtrack. It has since been published as a book and DVD set.3 In this project, Ware’s illustrated slides mimic both comics and architectural structure—like comics they proceed sequentially and occupy a small part of a large screen, and like architectural structure they construct patterns and structures on the screen, manipulating and concretizing space. Ware comments that one of the things that drew him to the project was its emphasis on Louis Sullivan’s early modernist architecture, which “seemed to be frozen life.”4 As a form, comics rely on dialectical relationships between the fragment and the whole; each panel is both discreet and bound to its predecessors and antecedents.

Ware’s phrase “frozen life” suggests an analogous fragmentation, a necessary episodic moment that can be observed in and of itself, yet also placed in a temporal continuum. As I will argue, Ware manipulates this relationship in complex ways that map other concepts—the relationship of the aesthetic to the vernacular, melancholy to pleasure, solitude to belonging, and history to the present—onto the formal structure of comics and the slideshow. In so doing, Ware’s comics and slideshow emphasize the collective visions, hopes, and dreams embedded in fragmented everyday life. For Ware, architecture is analogous to comics. This is made clear in The ACME Novelty Datebook, where Ware quotes Goethe’s claim that “architecture is frozen music” and then adds his own thought that “this is, I think, the aesthetic key to the development of cartoons as an art form.”5 Decaying and dilapidated architecture resonates as loss, as evidence of the irreversible passage of time, yet architectural ruins emanate past grandeur. Ware’s comics, then, focus on ruins and the melancholy they elicit in an attempt to render the irreversible passage of time into an aesthetic object. In both “Building Stories” and Lost Buildings, melancholy is remade into the imagination of the ruin as whole through an engagement with the built environment.

Chris Ware’s works are often populated with melancholic, despondent, shamed figures, unhappy and ill at ease with contemporary life. In his reading of Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, Brad Prager argues that Ware belongs to the modernist canon, alongside figures like Walter Benjamin, Sigmund Freud, and Franz Kafka, precisely because he “is committed to depicting the unhappy armor of everyday life and telling the impossible story of individual origins in the age of mechanical reproduction.”6 Douglas Wolk claims that Ware’s fixation on melancholy gives his comics “an emotional range of one note,” in part because “more than any other contemporary cartoonist except perhaps Robert Crumb, Ware is at home in the gallery-art world, which prefers its manifestations of pleasure-in-looking ironized—or, at least, held at arm’s length.”7 Unlike Prager, Wolk is impatient with Ware’s focus on alienation and argues that the alienation prevalent in works like “Building Stories” evidences Ware’s connection to the elite art world. Wolk’s populism, though, misses out on the very possibilities of negative critique that Prager emphasizes. Prager locates in Ware’s work a strong tendency to demystify industrial America as an artificial landscape, void of legitimate pleasures and fraught with psychic tension.

As the above example from “Building Stories” demonstrates, one of the major ways in which Ware stages this critique is by juxtaposing the past with the present, best exemplified by his recurring comparison of turn-of-the-century to contemporary Chicago. This emphasis on the past’s relationship to the present bears a striking similarity to Benjamin’s “Angel of History,” a figure articulated in his “Theses on the Philosophy of History” to allegorize the inability to know the past when our own position in the present is constantly in flux. Benjamin describes an angel “turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed” yet is blown forward by the winds of “progress.”8 Ware’s interest in nostalgia, childhood pleasures, and forgotten artifacts functions in a similar way. Ware’s depictions of architecture are not curatorial in nature but, like Benjamin’s “Angel of History,” strive to make the past total. Architecture is a vehicle to convey both the affective possibilities of experiencing the past as a whole and the perpetual frustration of the inability to reconstruct modernity’s ruins seamlessly. Ware’s focus on modernity’s ruins is an attempt, however impossible, to infuse everyday life with history.

In both “Building Stories” and Lost Buildings, architecture’s value hinges upon its status as both fragment and whole, ruin and complete structure. In “On the Museum’s Ruins,” Douglas Crimp argues that postmodern art emerges from a critique of what Walter Benjamin termed “aura,” the traces of originality, creative genius, and the artist’s presence in a work of art. Crimp writes, “Through reproductive technology postmodernist art dispenses with the aura. The fantasy of a creating subject gives way to the frank confiscation, quotation, excerptation, accumulation, and repetition of already existing images. Notions of originality, authenticity, and presence, essential to the ordered discourse of the museum, are undermined.”9 Crimp’s assertion that postmodernism creates works of art that are bound to a cultural network rather than to autonomous value elaborates upon Walter Benjamin’s famous argument, in “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” that photography and film change the terms of art, rendering concepts of “aura” and “authenticity” obsolete in the face of reproducibility.10

This shift in aesthetics from aura to reproducibility has progressed unevenly, and this unevenness is especially evident in the ways in which Ware’s work has been incorporated into museum discourse. For example, Daniel Raeburn’s monograph focuses on Ware as artist, with much attention paid to original line drawings, one-of-a-kind models, and artistic process.11 Gene Kannenberg Jr. also claims a kind of aesthetic aura for Ware’s work when he writes that Ware’s Quimby the Mouse “strip collections recall sonnet sequences, in that each page is a single unit and the aggregate whole is more concerned with communicating mood and feeling than in presenting narrative.”12 Kannenberg’s emphasis on Ware’s art as a whole object and an expression of a singular vision ignores the very conditions of both comics as a mechanically reproducible form and modern art. The above-mentioned two-page sequence in “Building Stories” embeds citation within its very structure by reproducing the same apartment building in different historical moments. For the characters in the present-day narrative as well as the reader, enjoyment emerges from the imagination, repetition, and citation of the past. Ware’s comics, then, certainly employ devices often attributed to postmodernism. Ultimately, though, the comics’ focus on the impossible feat of breathing life into history means that Ware is less interested in critiquing aura and authenticity than in charting aura as a historical phenomenon. Literary critic Jared Gardner argues that “the comic form is ideally suited to carrying on the vital work Benjamin called for generations earlier: making the present aware of its own ‘archive,’ the past that it is always in the process of becoming.”13 As Ware’s “Building Stories” demonstrates, this archival work entails not just artistic production but the very types of borrowing, citation, and contextualization emblematic of postmodern art. Ware latches onto neglected and ruined artifacts from modernism that bring to light paradoxically novel yet derivative aesthetic pleasures. That is, Ware’s work is best viewed as a catalog of modernism’s ruins, an archive that illuminates neglected, lost, and forgotten possibilities, as evident in the historical imaginings in “Building Stories” and Lost Buildings.

Ware’s aesthetic relationship to public space recalls another of Walter Benjamin’s subjects, the modernist figure of the flâneur, an aesthete who finds enjoyment in wandering through and observing urban space. Ware’s integration of a modernist aesthetic into a postmodern refashioning of traditional artistic categories creates a space for the reorientation of art toward emerging media and cultural formations. In his discussion of modernism and postmodernism, art historian T. J. Clark remarks that, in order to respond to rather than mimic our visual age, contemporary art must strike at “the founding assumption, the true structure of dream-visualization.”14 As Clark points out, one of these founding assumptions is the belief that reality itself is now entirely composed of images. One of the implications of this belief is that the world itself is entirely constructed and that in this age of new media and digitization, we are at the end of history.15 At first glance, comics seem to be a part of this postmodern image-world, owing to its two dominant poles of “continuity”-obsessed superhero material and independent, art comics that tend to be autobiographical in nature. The comics medium, in both cases, is self-contained and self-referential. In contrast, Ware’s graphic narratives challenge the apparent seamlessness of the form by focusing on the aesthetics of melancholy and fragmentation, exposing the contingency and impermanence of modern America. In its present form, “Building Stories” is itself a fragmented work, published in serial installments of The ACME Novelty Library and other periodicals. Ware thrives on the incomplete yet continually strives toward some totality. In so doing, his work locates renewed possibilities for pleasure, thought, and work from within history rather than outside of it.

Ware’s ongoing “Building Stories,” especially the segment published in The ACME Novelty Library 18, represents everyday life in the late twentieth century as inherently and irredeemably fragmented. While the apartment building is “sadly ignorant of the rejuvenating powers of renovation (or even restoration),” the female protagonist is painfully self-conscious: “‘Broken’ simply isn’t a strong enough word for what someone can do to your heart . . . it’s more like ‘annihilated’ or ‘punched out’ . . . but no word captures the undeniable, obliterated emptiness that having a ‘broken heart’ feels like . . . it’s as if I had a hole in me that I desperately wanted to fill, to turn myself inside out like a dirty shirt thrown on the floor, to pull myself backwards through the sleeve . . . anything . . . just to fill the void” (9, 43). The building’s lack of awareness and the protagonist’s “void” both result in ruination, and Ware’s depiction of the protagonist as ontologically incomplete implies that ruination is due less to a lack of maintenance than to the mere and inevitable passage of time. The final two-page spread in The ACME Novelty Library 18 returns to the building, presenting first its façade and then, on the facing page, its interior rooms with the façade removed (51–52). Unlike the female protagonist, the building is not constituted as a “void” here but as a repository of secrets, depth, and belonging. The narrative voice asks, “Who hasn’t tried when passing a building, or a home, at night to peer past half-closed shades and blinds hoping to catch a glimpse into the private lives of its inhabitants?” (51). This invoked curiosity is overlaid with the allure of “unspeakable secrets.” The building itself, then, is poised to fill the protagonist’s own “void.”

Ware’s “Building Stories” gestures to a possible way out of melancholy through the shared experience of living in the built environment and its potential to render the private sphere public. Nathalie op de Beeck remarks that Ware’s “Building Stories” “[urges] an illuminated awareness of looking, thinking, experiencing, and giving enhanced attention to the objects we produce and consume.”16 This “illuminated awareness” remains painfully unrealized by the protagonist in the existing “Building Stories,” and the sense of melancholy, of internalized loss, is literalized by the female protagonist’s prosthetic leg.17 She remains unable to experience her building as a stabilizing and grounding element in her seemingly empty life, yet Ware’s uses of architecture contain a promise of a richer life. Similarly, the collaborative slideshow project Lost Buildings makes clear that Ware’s goal is not simply to dramatize the emergence of a more engaged experience of everyday life within the narrative frame, but also to realize that experience in the reader or viewer. If Ware’s use of architecture is meant to “halt the flow of narrative time,” as Thomas Bredehoft argues, then it does so to infuse narrative with history, with context that destroys the narrative’s autonomy and forges connections to the experience of the viewer.18 While “Building Stories” gestures to an unrealized connection between subjects and history, mediated by the built environment, Lost Buildings offers a case study of what a richer lived experience might entail.

This richer lived experience emerges, in part, from the formal complexities of the slideshow. The images in Lost Buildings sometimes illustrate Glass and Samuelson’s remarks and sometimes depart from the audio to depict a separate scene. In the slideshow’s audio track, Samuelson narrates his childhood love of Louis Sullivan’s architecture, his involvement with Richard Nickel’s attempts to preserve Sullivan buildings and decorations, and Nickel’s tragic death during a collapse inside of the Chicago Stock Exchange Building’s wreckage. Nickel’s death parallels the loss of Sullivan’s architecture; both the photographer/urban preservationist and the architecture he died preserving are represented by illustrations drawn from Nickel’s photographs. This trace of the real, mediated through Ware’s meticulous, straight-edged drawings, renders Nickel’s project and the architecture as both real and imaginary, objective and subjective.

In his narration, Ira Glass discusses the melancholic predicament of Nickel’s and Samuelson’s love of Sullivan’s once underappreciated and now celebrated architecture: “If you love something the world doesn’t put any value on, you’re pretty much setting yourself up for a life full of heartbreak. One building after another that Tim loved, buildings where he had rooted around with Richard, they’re all gone.”19 Irrecoverable loss is a theme in many highly acclaimed graphic novels, most notably Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, and Art Spiegelman’s Maus. As Hillary Chute argues, comics lend themselves to the treatment of trauma, loss, and melancholy because they tend to “refuse to show [trauma] through the lens of unspeakability or invisibility, instead registering its difficulty through inventive (and various) textual practice.”20 Comics aim to work through traumatic loss, and Lost Buildings does this by bringing the very “lost buildings” referred to in its title back into temporary existence. During the slideshow, which was first shown during live performances of the This American Life radio show in large theaters, the audience experiences the presence of buildings now absent from contemporary Chicago. The DVD’s opening sequence makes a point of this original context. On a black screen, simple white letters read: “This was designed as a slideshow, not a movie. / It was originally presented on a darkened stage. The audio portion was read and mixed with music and quotes, live, in dim light, downstage left. The slides were advanced manually. / Pictures of buildings were tall as buildings. Even the smallest images were pretty big—three feet high. That’s one meter, if you’re watching this in Europe. / There are sections where the screen goes black. During those sections, the audience watched the audio be mixed, in the low light.”21 As the narrator and mixer, Ira Glass, along with the slide projectionist, lends a sense of immediacy and presence to the slideshow. It is notable here that the technologies used—audio mixing and slide projection—do not need to be operated in person. As on the DVD, they can easily be recorded and played in sync without on-stage mixing. The insistence on the slideshow’s original context on the DVD as well as the choice to perform the voiceover narration live points to Lost Buildings’ utopian promise: history can be incorporated into lived experience. This promise, though, can never be fully realized. The DVD will never truly replicate the experience of the live slideshow, just as the image of a building projected on a giant screen can never match the experience of walking around and through the building itself. As experienced on DVD, the slideshow calls attention to itself as a ruin of an earlier performance, subject to the same erosion of presence and experience as Sullivan’s architecture.

Lost Buildings is, of course, a departure from Ware’s typical medium of choice. The slideshow offers possibilities that are, significantly, amplifications of the intimacy, history, and readerly participation entailed in the comics form. In the late twentieth century, as curator Darsie Alexander argues, the slideshow became a way for artists such as Nan Goldin and Jack Smith to “structure their works around issues of subjectivity that often involved emotional, psychological, or social dilemmas.”22 Slide projection carries with it associations of family and community belonging, such as the vacation slide-show shown by a family to friends and relatives. Lost Buildings redirects these intimate and nostalgic connotations to the built environment. Instead of feeling affection for, and warm recollections of, vacations and family belonging, the audience engages with architecture as a sentimental object. Furthermore, the technology of slide projection seems obsolete in the twenty-first century, adding to the nostalgia of the project. By using this older form, and even more so by insisting on its priority even in the digital recording of the analog slideshow, Lost Buildings makes the obsolete proximate and reanimates the ruin.

In Lost Buildings, Ware manipulates the screen in a similar fashion to the way he structures a comics page.23 As Ware states on the DVD’s commentary track, he used “corners of the screen to stand for certain parts of the story [. . .] visually, I could put those similar parts of the story in the same part of the screen so that there could be some sort of visual connection.”24 The slideshow itself, as a medium, offers a parallel to comics in that Ware has a set frame, like a blank page or even a page with a more conventional grid of panels. Ware also remarks on the DVD commentary track that the slideshow images were frustrating because they would not be preserved in print: “Some of these drawings, especially the larger ones, would only be up on screen for a couple of seconds or so. And I’ve never had that feeling before, thinking, oh, I’m spending all of this time on a drawing, and it’s just going to end up vanishing after a second and a half.”25 The quickly vanishing images parallel the “lost buildings” themselves, evoking both immediate experience and its ephemerality. The slideshow’s pacing is analogous to the temporality of comics themselves, which, according to Art Spiegelman, are “a parade of past moments always presenting a present that is past.”26 Lost Buildings, then, expands upon a formal characteristic of comics by rendering the image in time as well as space.

Louis Sullivan himself described his work as aesthetic because of its roots in childhood experience. In his 1892 essay “Ornament in Architecture,” Sullivan remarks that in order to engage in artistic work, to create organic forms, one must “turn again to Nature, and hearkening to her melodious voice, learn, as children learn, the accent of its rhythmic cadences.”27 Lost Buildings also links organic form to childhood, using nostalgia and youthful whimsy to dramatize a sentimental connection to architecture. The slideshow begins with Tim Samuelson’s recollection of daydreaming in his elementary school classroom. As the teacher writes on the chalkboard, Samuelson imagines what the room must have looked like earlier in the century, “when the woodwork was still [pristine], instead of being really dark brown with all of this accumulated shellac that had turned color over the years, when it was a beautiful golden oak color and the brown wainscoting and the light fixtures with big glass globes hanging from the ceiling.”28 Ware’s slides first depict the young Samuelson, slouched at his desk, in small panels on the bottom right of the screen, and then show an enlarged drawing of the classroom, with inset panels representing Samuelson’s imagined original wood, moldings, and lighting. Samuelson then mentions that his childhood daydream even extended to the wall clock, remarking that he “wanted to get rid of the electric clocks and put the wind-up school clocks [back up. . . . I liked] the whole idea of having a clock that you could wind and hear the passage of time go tick tock, tick tock, tick tock.”29 With this statement, Ware presents a series of slides in the same panel on the screen, depicting a clock being wound and ticking, which slowly appears and reappears in a descending diagonal down the screen. For Samuelson, as for Ware, history is present through objects, and the passage of time entails a regretful decline in the value ascribed to those objects. Comics and the slideshow allow for their reanimation.

Ware’s slideshow further emphasizes Samuelson’s dreamlike approach to architecture when young Samuelson goes to see a Mr. Magoo film in Sullivan’s Garrick Theatre, just prior to its demolition. In this sequence, the slide-show departs from the audio track. Ware’s cursive script narrates Tim Samuelson’s thoughts: “I remember the first time I got to see the Theatre. / I told my mother I wanted to see a movie showing there . . . / . . . some dumb kid’s cartoon . . . / . . . but what I really wanted to see was the building. / I spent the whole time looking up at the arches, at the ornament, / illuminated by the flickering light of the film. / It was wonderful.”30 As these cursive words appear on the screen, connoting the same intimacy as they do in “Building Stories,” panels depict the young Samuelson going to and eventually sitting in the theater. The slideshow then illuminates sections of the Garrick Theatre’s decorative ceiling, while underneath these images is a lower tier of panels that shows the young Samuelson walking along a busy city street, looking up at the buildings. The other pedestrians are in black outline, and Samuelson is in full color. Samuelson is clearly privileged in these illustrations as an isolated individual who is able to make the quotidian experiences of sitting in a movie theater and walking down a city street into moments of aesthetic pleasure.

The disjuncture and solitude emphasized throughout the theater sequence by the bottom panels follows not only from Samuelson’s and Ware’s idea of melancholic aestheticism but also from Sullivan’s own social vision. As architectural historian William Jordy remarks, Sullivan thought in both hyperindividualist and collectivist terms, with no middle connections between the two: “[Sullivan’s] thinking jumped from an idealization of the creative self to an idealized abstraction of society. The void in Sullivan’s reasoning reflected both his personal solitude and a persistent lack in American culture. There was no sense of community in between [. . .] ornamentation on the one hand (the mark of the individual genius); the effect of the whole on the other (the sign of collective afflatus); something missing in between.”31 Lost Buildings, though, offers a resolution to this dichotomy. By involving the audience in the appreciation of ruined architecture, the building itself becomes an act of imagination and contemplation. While occupants of an actual Sullivan building might take it for granted in the rush of their everyday lives, those who never occupied one but imagine what one would be like bridge the gap between individual autonomy and collective belonging. Together, through the theatrical presentation of the slideshow, the audience experiences that which cannot be experienced in solitude but only as a member of a crowd: architecture in public space. The attempt to produce social belonging through engagement with aesthetic objects is a crucial component of Ware’s work, and one that adds warmth to what might otherwise seem to be a cold, precise drawing style that privileges form over emotion.

Ware rearticulates Samuelson’s love of Sullivan’s architecture in the slide-show’s structure. At one point, when Samuelson, as a young boy, makes his way into Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s office to beg him not to replace Sullivan’s Federal Building, Ware’s slideshow mimics a cartoon film. This shift, from largely individual slides following the narration and a mellow, contemplative soundtrack, to a jazzy film narrative ironically dramatizes Ware’s own sense that comics should be distinct from film, just as Louis Sullivan’s organic, detailed buildings are distinct from Mies van der Rohe’s formalist style. Sullivan’s buildings connote warmth, intimacy, and depth, while Mies van der Rohe’s buildings seem by contrast cold, distant, and shallow. To dramatize this aesthetic difference, the slideshow slips into the less-than-serious mode of a Mr. Magoo cartoon, referencing the earlier moment in the slideshow when Samuelson prefers to look at the ornate ceiling of Sullivan’s Garrick Theatre than watch the “dumb kid’s cartoon” projected on the screen.32 As Chip Kidd reports, “Angered by the notion that comics are closely related to film, Ware argues that film is a ‘passive medium’ requiring primarily from its audience the ability to sit and stare. Comics at their best engage the viewer in a different manner, allowing readers to help control the pacing either by taking in a page at once, or by reading panel by panel.”33 Ware’s manipulation of the slide-show’s pacing seems to be another expression of this resistance to readerly passivity. By embedding within the slideshow a filmic sequence, Ware strives to differentiate the slideshow from film. The Mies van der Rohe sequence, with its formal departure and upbeat soundtrack, opposes the more serious discussion of Sullivan’s architecture. This portion of the slideshow points to a radical break between the ornate early modernism of Sullivan and the institutional, formalist modernism of Mies van der Rohe. Furthermore, Mies van der Rohe’s architecture is cast as a style that permeates every facet of modern life, especially with the slide that notes: “Ironically, Tim now lives in a Mies van der Rohe building.”34

In the filmic sequence, young Samuelson is given a hearing with Mies van der Rohe, who, with his iconic eyeglasses, is drawn as Mr. Magoo, making literal his supposed inability to see the beauty of the Sullivan building he was preparing to replace. After pleading for the Sullivan building, Samuelson, in a performed German accent, ventriloquizes Mies van der Rohe’s response: “Someday I hope you look at the new building and see many of the qualities you admired in the old.”35 Instead, Samuelson privileges vanished traits over new structures. As Ira Glass comments during the slideshow, “Whenever Tim walks in Chicago, he sees not just the buildings that are there; he sees the buildings that used to be there. The whole skyline is haunted for him.” Samuelson’s “haunted” city also illuminates a more complex aesthetic statement about the necessity to view the built environment as a historical entity. Paralleling the dialectical relation in comics between the fragment and the whole, the panel and the page, the page and the text, Lost Buildings stages a dialectical relationship between lived experience and history, individuality and the built environment.

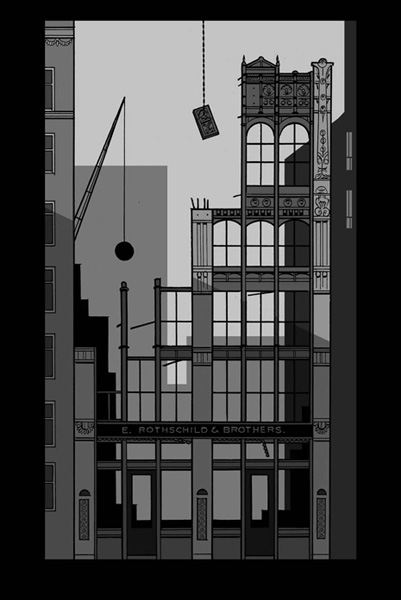

Fig. 8.1. A crane lowers a cast-iron panel from the ruins of Louis Sullivan’s Rothschild Building in Lost Buildings. Lost Buildings, produced and performed by Ira Glass, Tim Samuelson, and Chris Ware, DVD, This American Life, WBEZ Chicago, 2004.

Lost Buildings builds an even more subtle association between architecture and comics in its use of insets. In one slide, after Samuelson discusses Nickel’s death, we see a large drawing of the Federal Building that replaced Sullivan’s Chicago Stock Exchange Building. Ware illustrates the building, like many of the other large slides of architecture, head-on, exhibiting the homogenous panels of windows so emblematic of both the modern skyscraper and the conventional comics grid. These regimented panels, however, are broken up by an inset panel, a circle which at other moments in the slideshow is a wrecking ball and a kind of peephole into childhood. This circular inset features, first, rubble, then a piece of stair stringer, and, finally, a hardhat atop a table. These images are repeated from an earlier moment in the slideshow about Richard Nickel’s death. The inset circle, then, interrupts the modern building’s homogenous structure and serves as a space for memory and remembrance, while also playing with the conventional comics grid. Haunted by the new building, Samuelson looks forward to the day when it too will be demolished to make way for something different.

If Mies van der Rohe’s architecture is impersonal, then Sullivan’s buildings are remarkable because of their ability to produce feelings of warmth and intimacy. The ornamentation of Sullivan’s buildings is central to Samuelson’s feelings about them. Architectural critic Mark Wigley argues that Sullivan’s notion of organic form relies on the intertwining of ornament and structure: “Sullivan’s call for a removal of ornament is not a call for the eradication of ornament. On the contrary, it is an attempt to rationalize the building precisely to better clothe it with ornamentation that is more appropriate and more carefully produced [. . .] despite the ‘fashion’ to consider ornament as something that can be either added or removed from a building, ornament can never be simply separated from the structure it clothes.”36 Ornament, then, is not an additive to Sullivan’s buildings but an integral part of the architecture. Lost Buildings mourns the loss of these total structures, despite the fact that there are a number of Sullivan buildings that have been preserved in Chicago. The ruination of Sullivan’s buildings, though, provides an occasion for a more intense appreciation of ornament not in and of itself but as a synecdoche for these larger yet lost structures. Nickel’s photographs and Ware’s drawings document the erosion of the connection between ornament and structure, and they demand that the viewer imagine the whole from the fragment. One of Ware’s large building images depicts the demolition of Sullivan’s Rothschild Building (see fig. 8.1). In that image, we see a crane lowering a cast-iron panel. Decorative fragments such as this are pictured throughout the slide-show; they are key to Sullivan’s aesthetic and are often the only surviving artifacts of Sullivan’s buildings. These fragments emanate the larger architectural forms to which they once belonged, and the slideshow—a fusion of Ware’s large, projected images and Glass’s interpretation of Samuelson’s aesthetic into a sympathetic, whimsical, and admirable worldview—asks the audience to imagine the built environment as historical and the ruin as a whole. These two processes rely on one another. Through imagining history less as a catalog of artifacts or relics but as a lived experience, a rich social fabric, one reconstitutes ruins as total objects. This revival of the ruin as a whole object is less a process of aesthetic isolation than contextualization. The ruin is rendered whole by imagining it in relation to and amidst historical life. Like the impossible archival mission of Benjamin’s “Angel of History,” though, we can never fully reconstitute the whole from the ruin. Lost Buildings embraces a necessarily incomplete yet never-ending desire to experience the past from the unstable vantage point of the present.

In “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” Benjamin remarks that one of the ways in which we imagine possible futures is through recognizing the inevitable ruination of the present. His beloved Parisian Arcades, he writes, allow us to “begin to recognize the monuments of the bourgeoisie as ruins even before they have crumbled.”37 The final slide of Lost Buildings depicts the stark, steel and glass office building on the site of Sullivan’s Chicago Stock Exchange in ruins, with a wrecking ball in the midst of its broken middle. In that wrecking ball’s black interior, Ware writes “The End,” gesturing to the inevitable ruination of the present. Thinking of these modern buildings as also in ruins points to the ways in which the qualities of our own lives, our lived experiences—which for Ware are saturated with melancholy, unfulfilled longing, and isolation—are themselves constructed and historical. One of the problems presented by our contemporary moment is, as Fredric Jameson remarks, “one of representation, also one of representability: we know that we are caught within these more complex global networks, because we palpably suffer the prolongations of corporate space everywhere in our daily lives. Yet we have no way of thinking about them, of modeling them, however abstractly, in our mind’s eye.”38 What Chris Ware’s work on and about architecture shows us is that this “modeling” of the present can only occur in relation to the past. By imagining the past and asking us to experience it in our daily lives, Ware’s work contains a utopian wish that images and history can enrich everyday life. Chris Ware’s work documents the melancholy realization that ruin is inevitable, yet finds in those ruins a renewed possibility for aesthetic experience.

1. Chris Ware, The ACME Novelty Library 18 (Chicago: The ACME Novelty Library, 2007), 23, 25. All further references to this text will be indicated in parentheses.

2. Lost Buildings, prod. and perf. Ira Glass, Tim Samuelson, and Chris Ware. DVD and book. WBEZ Chicago, 2004.

3. I saw Lost Buildings performed live as part of This American Life’s “Lost in America” tour in Boston, May 2003. According to the DVD booklet, the slideshow “was originally commissioned by UCLA Live’s spoken word series at Royce Hall in Los Angeles” and was performed at a handful of venues in 2003 and 2004. The Lost Buildings DVD was published by This American Life, the Chicago Public Radio show hosted by Ira Glass, and it is available through This American Life’s Web site: http://www.thisamericanlife.org. Ira Glass and Chris Ware have more recently collaborated on animated segments for the This American Life television program on Showtime.

4. Chris Ware, “Introduction,” Lost Buildings, n.p.

5. Chris Ware, The ACME Novelty Datebook (Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2003), 190.

6. Brad Prager, “Modernism and the Contemporary Graphic Novel: Chris Ware and the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” International Journal of Comic Art 5.1 (2003): 211–12.

7. Douglas Wolk, Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo, 2007), 347, 351. For an analysis of Ware’s ambivalence about his place in the art world, see Katherine Roeder’s essay in this volume.

8. Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken, 1969), 257–58.

9. Douglas Crimp, “On the Museum’s Ruins,” October 13 (1980): 56.

10. Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in his Illuminations, 220–22.

11. Daniel Raeburn, Chris Ware (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 44–53.

12. Gene Kannenberg Jr., “The Comics of Chris Ware: Text, Image, and Visual Narrative Strategies,” in The Language of Comics: Word and Image, ed. Robin Varnum and Christina Gibbons (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 178.

13. Jared Gardner, “Archives, Collectors, and the New Media Work of Comics,” Modern Fiction Studies 52 (2006): 803.

14. T. J. Clark, “Modernism, Postmodernism, and Steam,” October 100 (2002): 173.

15. For the “end of history” thesis, see Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Avon, 1992).

16. Nathalie op de Beeck, “Found Objects (Jem Cohen, Ben Katchor, Walter Benjamin),” Modern Fiction Studies 52 (2006): 827.

17. For a further analysis of the narrator’s disability in “Building Stories,” see Margaret Fink Berman’s essay in this volume.

18. Thomas Bredehoft, “Comics Architecture, Multidimensionality, and Time: Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth,” Modern Fiction Studies 52 (2006): 885.

19. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations from Lost Buildings are from text on screen during the slideshow or its accompanying audio track. The Lost Buildings DVD contains both a Quicktime version of the slideshow, which more accurately reflects the size of the screen during live performances, and a movie version tailored to fit a television screen.

20. Hillary Chute, “Comics as Literature? Reading Graphic Narrative,” PMLA 123 (2008): 459.

21. Lost Buildings.

22. Darsie Alexander, “Slideshow,” in Slideshow: Projected Images in Contemporary Art, ed. Darsie Alexander (University Park: Baltimore Museum of Art/Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005), 27.

23. The way that Ware uses the screen in Lost Buildings seems analogous to Thierry Groensteen’s concept of “arthology,” which describes the relations in comics between each individual panel and the work’s structure as a whole. See Thierry Groensteen, The System of Comics, trans. Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007), 103–58.

24. Lost Buildings DVD Commentary.

25. Ibid.

26. Art Spiegelman, “An Afterword,” in his Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*! (New York: Pantheon, 2008), n.p.

27. Louis Sullivan, “Ornament in Architecture (1892),” in Louis Sullivan: The Public Papers, ed. Robert Twombly (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988), 84.

28. Lost Buildings.

29. Ibid.

30. Ibid.

31. William Jordy, “The Tall Buildings,” in Louis Sullivan: The Function of Ornament, ed. Wim de Wit (New York: Chicago Historical Society/Saint Louis Art Museum/Norton, 1986), 149.

32. Lost Buildings.

33. Chip Kidd, “Please Don’t Hate Him,” Print 51.3 (1997): 46, 49.

34. Lost Buildings.

35. Ibid.

36. Mark Wigley, White Walls, Designer Dresses: The Fashioning of Modern Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1995), 62–63.

37. Walter Benjamin, “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, ed. Peter Demetz, trans. Edmund Jephcott (New York: Schocken, 1978), 162.

38. Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism; or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991), 127.