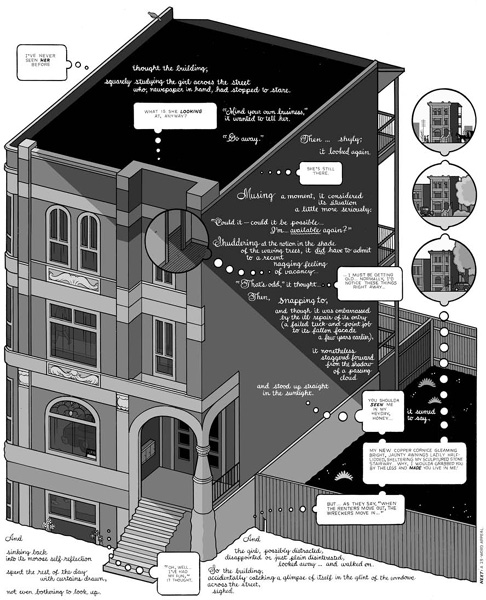

In part 1 of Chris Ware’s serialized comic strip, “Building Stories,” readers are introduced to a three-story row house in Chicago’s Humboldt Park. Ware represents the building as a character that struggles to interpret the motives of a woman who, newspaper in hand, studies it from across the street (see fig. 9.1). Although we can’t see the woman directly (only her torso and legs are reflected in one of the building’s windows), and despite the fact that we don’t know why she’s scrutinizing the building, the mere fact of her presence sends the building spiraling through a welter of emotions. Initially uneasy— “‘Mind your own business [. . .] Go away,’” it silently urges the woman—the building changes its tone as it “admit[s] to a recent nagging feeling of vacancy” and realizes that the woman’s presence can mean only one thing: it is “available again.” Now, fully alert, the knowledge that one of its apartments is indeed vacant and that the woman must be considering renting it enlivens the building and it tries its best to woo her by “stagger[ing] forward from the shadow of a passing cloud and stand[ing] up straight in the sunlight.” In the end, though, the woman walks on, seemingly rejecting the building, and it “sink[s . . .] back into its morose self-reflection [. . .] spend[ing] the rest of the day with curtains drawn, not even bothering to look up.”

Culled from an ongoing series which Ware has published intermittently since 2002, “Building Stories”’ nearly seven-month run in the New York Times Magazine recounts a day (September 23, 2000, specifically) in the life of the building and its four inhabitants: the young, single woman from the opening panel, who eventually does rent the vacant room, an unhappy couple on the floor below, and an elderly landlady. Although much of “Building Stories” focuses on the lives of these inhabitants, Ware’s personification of the building suggests that he is just as interested in its life as he is the actions of his characters. Indeed, parts 2 and 3, which feature a nearly identical image of the building and are wholly devoted to its interior monologue and to establishing its history in the neighborhood, cement the building’s characterization as an omniscient presence whose story frames and guides readers through the strip.

As the inaugural installment of the New York Times Magazine’s “Funny Pages,” “Building Stories” provided Ware with what is almost certainly his largest exposure to a mainstream reading audience to date. Given this exposure, and given the high-profile nature of the strip’s selection as the first of the magazine’s ongoing series of graphic fiction, Ware’s rather idiosyncratic decision to focus on the life of a building seems curious at best. Further, it begs the question why he would foreground the building’s story over the lives of the various characters that also inhabit the strip. To understand why Ware goes to such lengths to bring to life a character as seemingly mundane and static as a three-story apartment building, it is necessary to consider Ware’s keen interest in the experiential power of architectural space and the building’s place in the context of ongoing debates about Chicago’s gentrification.

Fig. 9.1. Ware’s text in this scene both humanizes the building and comments on the action taking place around it. Chris Ware, “Building Stories: Part 1,” New York Times Magazine, September 18, 2005, 41.

A process by which an influx of affluent, mostly white homeowners and renters move into an economically depressed area, gentrification is the result of a depressed housing market caused by postwar white flight, the growth of the suburbs, and inner-city disinvestment.1 Since the late 1960s, as new residents began to realize that urban living provided them with the opportunity for affordable housing, they have transformed districts by demolishing or completely renovating decaying inner-city neighborhoods. Historic buildings play a complex role in this process as they have become the primary vehicle by which gentrification takes place as well as a focal point for critics and protesters who see the maintenance of unrenovated housing stock as integral to resisting a process that threatens to redefine American cities along ever more rigid economic lines.

Ware’s attention to the inner life of the row house can be read as a tribute to aging buildings whose presence in U.S. cities is rapidly diminishing. Moreover, Ware seeks to inculcate in his readers an appreciation for historic buildings, a position he advances in his writings on architecture and buildings. Throughout his career, Ware has linked his work as a cartoonist to the art of architecture and, in doing so, expressed a passion for sites that are no longer valued in contemporary urban economies.2 In this context, we can understand the intimate portrayal of the house in “Building Stories” as an implicit plea against the demolition of historic buildings. By humanizing structures typically viewed as a lifeless assemblage of brick, steel, and wood, Ware seems to be suggesting that rather than taking such a building for granted, ignoring the role it has played in the life of the neighborhood, we should instead recognize its history and celebrate its role in the urban environment.3

More than simply a paean to historic buildings, though, “Building Stories” manifests Ware’s belief that close attention to the affective and intangible aspects of buildings, the psychic and emotional lives they contain, offers a corrective to twenty-first-century American cities and the constant push for progress at any cost. Specifically, Ware praises historic buildings from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for their beautiful ornamentation and the loving attention to detail that went into their design and construction. Perhaps nowhere is Ware’s passion for historic buildings more evident than in his devotion to the buildings of Louis Sullivan. An early mentor to Frank Lloyd Wright, and considered by many to be the father of modernism and modern architecture, Sullivan designed buildings adorned with ornate, intricate façades that have long inspired Ware.4 Writing in the introduction to Lost Buildings, a DVD produced by This American Life that documents efforts to preserve Sullivan’s surviving buildings in Chicago, Ware says he shares an artistic sensibility with Sullivan and particularly appreciates his use of ornamentation to express the public nature of architecture. Lauding Sullivan’s buildings as important works of art, Ware argues that these buildings, more than most places in which people live and work, “seemed to be frozen life— the very force and shape of ideas, will, and love itself.” Ware continues by noting that Sullivan’s “‘ornament,’ sometimes wrongly dismissed as secondary to the structure, was always inextricably important to every building he designed, growing out of the fundamental idea and shape of each commission, and, in his own words, ideally admitting to the ‘reality and pathos of man’s follies.’”5 By contrast, he finds contemporary architecture to be “ghastly and antiseptic,” arguing that “modern buildings [. . .] mock people. They don’t elevate them or inspire them—they just contain them,” and suggests that Sullivan’s sensibility is sorely missed in contemporary urban landscapes.6

Ware’s connection to the lives of historic buildings underscores and begins to explain the strip’s focus. Throughout its seven-month run, Ware creates a fully developed character with a long, rich history in the neighborhood. In part 1, for instance, a series of images indicates the building’s age. Thus, in this opening panel, three small insets on the right side, depicting images of the building with different vehicles in front—a horse and carriage, a Model T Ford, and a contemporary car—evoke the building’s years of service to residents in the neighborhood. Part 2 further emphasizes this service when it highlights the fact that the classified ad used to advertise vacant rooms was “composed more than half a century ago and preserved unaltered (minus minor monetary updates) on a limp, well-thumbed index card [. . . and] has shar[ed] space with decades of war, recession and various presidential administrations.” Part 3, in turn, brings the building’s history up to date by noting that the aforementioned woman has, in fact, rented the vacant apartment, joining the generations of renters who have sought shelter in its walls, and depicting a schematic of the building that recounts in exacting detail everything it has witnessed throughout its life. By eschewing a conventionally linear narrative and combining the past, present, and future in a single frame, Ware represents the life of the building as a coherent whole, humanizing an otherwise insentient object and imbuing it with affective value.7

Ware’s use of comics and of comics’ conventions to personify and amplify the life of an aging apartment building can be read as a critique of gentrification and the entire system of contemporary urban renewal that strips such sites of their artistic and historical value.8 “Building Stories” condemns the erasure of much of the physical and cultural history of U.S. cities in the name of progress, reconsidering buildings’ status as more than mere commodities in a neoliberal urban economy that is increasingly defined by the tenets of privatization and economic homogenization.9 When Ware humanizes the building, emphasizing its service to the neighborhood, he minimizes the factor that most defines the lives of buildings in contemporary U.S. cities: their status as commodities in the urban real-estate market. This reversal emphasizes the row house’s human characteristics and asks us to see it not as an object but as a person with a history, and to relate to it on a level that transcends typical object relations. Ware thus offers a new perspective on the dwellings where we live and, more importantly, shows their importance in preserving the social and public life of our cities. More specifically, “Building Stories” seems to suggest that old buildings such as the one whose life he documents occupy a special place in urban economies, serving as repositories of the promise of cities to attract and house populations often marginalized by the mainstream, majority culture.

The implications of this stance are made clear when we consider that the building’s location in the rapidly gentrifying neighborhood of Humboldt Park positions it as a bulwark against this process and, by extension, the economic homogenization of public life. According to criminal justice professor Jeff Ferrell, as gentrifiers move into inner-city neighborhoods they, along with local governments and developers, create “new cultural spaces [that] redesign city life along new lines of spatial exclusion, and [. . .] organize new forms of control against those deemed foreign to these spaces.”10 Ferrell suggests that gentrification creates exclusive, affluent neighborhoods and communities through a variety of private forces (neighborhood boards, historic preservations statutes, corporations, etc). As a result, inner-city neighborhoods are no longer defined by their ability to serve basic needs, such as shelter, food, and community, but rather they become “urban growth machines” that are designed to provide profitable returns on the investments of the homeowners, businesses, realtors, and private developers who invest heavily in an area’s redevelopment.11

Ware overtly addresses the issue of gentrification in part 26 when Tom, an African American character, who only appears once in the strip, sarcastically thanks the young white woman from the opening panel for making Humboldt Park “safe” for North Siders. Tom’s comment alludes to the influx of wealthy, typically white residents to Chicago’s historically black South Side neighborhoods. Moreover, his remark refers to the fact that gentrification targets sections of the city that have been coded as black or Latino and poor, rendering them “suddenly valuable [. . . and] perversely profitable.”12 Humboldt Park, where “Building Stories” is set, is an instructive example of this process. In postwar Chicago, the neighborhood began to attract larger numbers of Puerto Rican families who, though marginalized within the city as a whole, “managed to cultivate a strong sense of community built around a proud Puerto Rican identity.”13 Since the mid 1990s, however, it has been transformed by middle-class homeowners and the construction of luxury apartments and upscale developments.14 Gradually, young, white, middle- to upper-middle-class homeowners and families have moved into the area, raising property values and displacing many Puerto Rican families. As a result of these changes, a rift has formed between the Puerto Rican community and the new residents. During the early 1990s, families “started hearing rumors from neighbors that developers were taking an interest in the area because of its proximity to Chicago’s downtown, and to major modes of transportation.”15 Today, Humboldt Park has emerged as one of the most contested sites in Chicago and the tension between working-class Puerto Ricans and affluent gentrifiers exemplifies current debates about gentrification.16

When Ware locates his building in Humboldt Park, he implicitly asks readers to consider why he places a thinking and feeling building in the midst of a rapidly gentrifying Chicago neighborhood. Initially, his decision seems to suggest that the strip is intended to evoke the issues facing residents of gentrified neighborhoods. Thus, when the young woman comments in part 27 that she didn’t like how Tom was “all in [her] face about that ‘gentrification’ stuff,” the strip raises race and class tensions inherent in a gentrifying neighborhood. And yet, by deferring references to gentrification until late in the strip, Ware appears loath to offer an explicit opinion on the issues of race and class attendant in discussions of the process.17 Instead, the comic provides a more nuanced reading that does not indict the gentrification of a specific site, Humboldt Park, but speaks to a concern for urban landscapes and about what our treatment of historic buildings signals for the future of U.S. cities.

Gentrification is just the latest manifestation of a “penchant for destroying the old” in American cities.18 As urban planners and politicians have promoted a “cycle of destruction and rebuilding as ‘second nature’—self-evident, unquestionable, and inevitable”—they have continually ignored the inherent value of buildings that seemingly have little to no practical or economic use.19 This mentality has contributed to the ongoing commodification and privatization of public spaces and has given rise to a culture that fails to recognize the importance of place, emphasizing instead “the nexus of production and finance capital at the expense of questions of social reproduction.”20 Increasingly, cities are defined by the tension “between the notion of ‘place’ versus undifferentiated, developable ‘space.’”21 Urban geographers James Logan and Harvey Molotch describe this same tension as the split between use value and exchange value in urban space. In the former, a particular site, whether a neighborhood or, in this case, a building, is valued because it “satisf[ies] essential needs of life” and provides a psychological and emotional fulfillment; in other words, “space” becomes “place” when there is a human connection to a structure, whether it is a house or an apartment.22 “Space,” by contrast, is simply a commodity whose value resides in the amount of capital, whether financial or cultural, a developer, an individual, or even an entire city can get for it.23

The difficulty of such a system is that exchange value is by definition contingent and transient. In urban real estate, this means that what is valuable and desired today will be seemingly useless and unwanted tomorrow, and, as a result of spaces constantly being redefined and recontextualized, the past must be ignored and elided in order to create conditions necessary for the redevelopment of a certain site. This elision is deemed necessary because contemporary cities rely on success in global markets such as tourism to succeed and are “invest[ed . . .] in selling their places [. . .] through a narrative of success” given that “a negative image may encounter greater difficult in attracting the levels of investment required to revise the competitive position of their economies.”24 Moreover, such a marketing campaign “succeeds only to the extent that it can distance itself from the immediate past,” whether that past is codified as a working-class slum, African American ghetto, or, as in the case of Humboldt Park, Puerto Rican enclave.25

The representation of Humboldt Park in “Building Stories” implicitly challenges the rhetoric of politicians and developers who promote gentrification as a naturally occurring symbol of a bright future for U.S. cities. The strip resists a system of renewal that values buildings for their power to generate profit and promotes a perspective that recognizes their social function in an urban economy. When Ware writes in “Lost Buildings” that he is heartened to see a cultural turn toward preserving buildings that seemingly have little to no exchange value, he is in essence valuing place over space. “Building Stories” enacts a similar reversal as exemplified by the perspective presented in part 3’s schematic depiction of the building. As we learn in part 2, rent for the building’s apartments has long been “utterly out of touch with local housing prices.” While this means that the building has not maximized profits for the elderly landlady who lives in the first-floor apartment, it has made it possible for a “perpetual parade of bargain-seeking applicants” to find affordable housing in the neighborhood. Part 3 diagrams how the building links all three eras simultaneously, thanks to the fact that its low rent makes it as accessible to individuals who cannot afford higher prices (see fig. 9.2).

Laying bare the social life of the building, Ware decries the physical and psychological destruction of urban spaces caused by gentrification. This stance is perhaps most evident in the melancholic tone that pervades the strip and that contributes to the representation of the building as a character whose fate is uncertain. Despite being fully occupied, the building is wistful for earlier times, worried that its low rent and old-fashioned façade is out of touch with changes in the neighborhood. Ware’s message is made even more explicit at the end of the strip with the building’s growing awareness that its time is limited. Part 29 shows the building’s increasing anxiety about the health of its landlady as it fears she might die soon and begins to ponder its future: “Here’s where my concerns begin. Now, the long-burning lamp of my long-yearning landlady seems to fray, falter, and fizzle [. . .] So then, what? The thought of such utter vacancy fills me with dread unlike any other.”26 While the building fears that the death of the landlady portends an uncertain future, readers know it has real reason to be worried—the landlady is all that stands between it and a real estate speculator or new owner who would renovate it, thus driving up prices, or, worse still, demolish it.

It is here that the strip most clearly emerges as a statement on city life and urban planning; specifically, it forms a powerful argument against current trends in urban redevelopment and acts as a call to redress the damages caused by the redevelopment of American cities. This reading is bolstered when the strip is read alongside the work of Jane Jacobs and her 1961 treatise on how to fix the nation’s cities, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Jacobs demands that city planners and politicians preserve aging structures, writing that cities “need old buildings so badly it is probably impossible for vigorous streets and districts to grow without them [. . .] Not museum-piece old buildings, not old buildings in an excellent state of rehabilitation [. . . but] a good lot of plain, ordinary, low-value buildings, including some rundown old buildings.”27 Jacobs’s praise for old buildings mirrors the sentiments evoked by “Building Stories” more than thirty years later; namely, she recognizes that demolishing or rehabilitating old homes in order to maximize their economic value sends a discouraging message about the values and beliefs of the politicians and developers who are reshaping U.S. cities.

Jacobs asserts that the bottom line has managed to take precedent over all other concerns in city-planning decisions. “Price tags,” she writes, “are fastened on the population and each sorted-out chunk of priced-tagged populace lives in growing suspicion and tension against the surrounding city.”28 The tension Jacobs describes is, according to cultural critic Lewis Hyde, a function of the commodification of places and an all-consuming desire to attain material wealth. Real wealth, he writes, the intangible kind produced by gifts and works of art, “ceases to move freely when all things are counted and priced. It may accumulate in great heaps, but fewer and fewer people can afford to enjoy it.”29 Similarly, Jacobs fears that cities become stagnant when they cease to be able to facilitate the production or consumption of the kind of wealth Hyde describes. Time and again she returns to the idea that the city is a refuge for those people for whom ideas and imagination, not profit and statistics, matter.30 Thus, Jacobs yearns for traditional urban neighborhoods that have served as havens for populations marginalized by mainstream American culture and that, increasingly, have been lost as homes and the surrounding areas are being redefined as pure commodities.31

Fig. 9.2. Part 3’s schematic connects the past to the present and evokes the building’s integral role in the lives of its inhabitants. Chris Ware, “Building Stories: Part 3,” New York Times Magazine, October 2, 2005, 39.

The commodification of homes has intensified as urban living has come to represent a popular lifestyle decision as well as a sound investment for affluent residents anxious for affordable housing that provides access to increasingly trendy neighborhoods.32 The last episode of “Building Stories” suggests the hidden dangers of this process. Although the penultimate scene, part 29, closes with the building merely afraid of what the death of its landlady signifies, the epilogue, which takes place five years later, suggests that these fears are realized. In this episode, the young woman and her daughter have returned to the neighborhood where she once lived (see plate 13). Noting the presence of a Starbucks and of a new boutique clothing store titled, fittingly, “Niche,” she realizes how much the neighborhood has changed. Indeed, the landscape has the look and feel of a corporate space that is designed to meet the consumption needs of an affluent new population rather than the day-today needs of the poor, working-class residents and, in this case, Puerto Ricans who have long called it home.33

“Building Stories” has come full circle, but the intervening five years have redefined what the building symbolizes to the woman and, by extension, to the neighborhood at large. Unlike before, when the building’s cheap rent connoted the possibility of a new life, now the woman stares at a building that is no longer owned by the original landlady and features a “For Rent” sign; apparently the structure has been renovated recently and a sign next door indicates it will soon be bordered by luxury condominiums. As these images suggest, Tom was right—the neighborhood is now safe for North Siders: both the Starbucks and the boutique, while meant to meet the consumer needs of a new class of residents, also indicate that the neighborhood has been suitably gentrified. Comforted by what have come to be common symbols of a gentrified neighborhood, new and potential residents can rest assured that the site’s history as a working-class, ethnically heterogeneous neighborhood has been erased in favor of a new identity as an upscale enclave.

More tellingly, the building has been silenced. Gone is the character we encountered throughout the strip and in its place is a building whose presence in the neighborhood appears tenuous at best and whose links to the neighborhood’s past have vanished. The implications of this silencing are, according to Jacobs, immense: cities are no longer able to meet the needs of an economically diverse population by providing an opportunity for a better, or different, life than the one they previously led. “Hundreds of ordinary enterprises,” she writes, “necessary to the safety and public life of streets and neighborhoods, and appreciated for their convenience and personal quality, can make out successfully in old buildings, but are inexorably slain by the high overhead of new construction.”34 Nor is Jacobs alone in sounding a death knell for the traditional city. Countless critics and observers have mourned the loss of public life in urban landscapes. Writing in the late 1970s, Phillip Aries noted that in post-industrial American cities, “what is truly remarkable is that the social intercourse which used to be the city’s main function has now entirely vanished.”35 Implicit in these arguments is a sentiment echoed by Ware’s depiction of the building’s loving service to the neighborhood: an unmistakable sense of loss and of concern for what gentrification has visited on the experience of everyday life for people in America’s cities and throughout the United States.

Ware’s vision of the city resists the prevailing view that capitalism and the capitalist ethos are the best and only option for progress. Instead, his building offers a vision of urban life where the possibility exists for sites and buildings defined not by the continued hyper-commodification of spaces and buildings but rather by their emotional, subjective presence and their ability to house populations marginalized and peripheralized within the current system. Ware’s strip, although it features a building that eventually succumbs to gentrification, implicitly criticizes what Michael Sorkin has termed the “departicularizing” of the contemporary city.36 Arguing that urban landscapes today are dominated by the spread of “globalized capital, electronic means of production, and uniform mass culture” Sorkin writes that in contrast to the “undisciplined differentiation of traditional cities [. . . t]he new city replaces the anomaly and delight of such places with a universal particular, a generic urbanism inflected only by appliqué.”37As a living and breathing link to the history of the neighborhood where it is located, a structure that personifies the personality and unique identity of that space, Ware’s building resists the “generic urbanism” Sorkin fears and the economic homogenization gentrification entails. “Buildings Stories” recognizes that buildings contain “the back and forth oscillations of time and memory, past and present” and, in doing so, provide us with hope for the future of U.S. cities.38 Guarding against gentrification, the maintenance and preservation of historic buildings can forestall the transition to a generically corporate landscape of boutiques and corporate chains—what Sorkin calls the “repetitive minimum” that now defines most inner-city neighborhoods. Deprived of older buildings, Humboldt Park and neighborhoods like it risk reducing cities like Chicago to an anonymous every-city, in which urban landscapes are devoid of the exhilarating public life that has defined city living for generations.

1. Chris Hamnett, “The Blind Men and the Elephant: The Explanation of Gentrification,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 16 (1991): 173–89. Hamnett provides a thorough definition of gentrification as well as an overview of the critical literature and debates surrounding it.

2. Chris Ware, The ACME Novelty Date Book (Amsterdam: Oog and Blik, 2003), 190. Here, Ware includes Goethe’s dictum, “architecture is frozen music,” and argues that it is the “aesthetic key to the development of cartoons as an art form” (190).

3. Daniel Raeburn, Chris Ware (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 96. In an interview with Raeburn, Ware suggested that “Building Stories” is the work that is closest to him and to the way he thinks.

4. Hugh Morrison titled his 1935 biography of Sullivan, the first major biography of the architect, Louis Sullivan: Prophet of Modern Architecture. Hugh Morrison, Louis Sullivan: Prophet of Modern Architecture (New York: Norton, 1998).

5. Lost Buildings, prod. and perf. Ira Glass, Tim Samuelson, and Chris Ware. DVD and book. WBEZ Chicago, 2004.

6. Chris Ware, “You Are Here,” in Marc Trujillo: You Are Here, Hackett-Freedman.com, 2006, http://www.hackettfreedman.com/templates/catalogueEssayPopup.jsp?id=1144 (accessed July 7, 2008); Beth Nissen, “An Interview with Chris Ware,” CNN.com, October 3, 2000, http://edition.cnn.com/2000/books/news/10/03/chris.ware.qanda/ (accessed June 25, 2008).

7. Chip Kidd, “Please Don’t Hate Him,” Print 51.3 (1997): 42–49.

8. Hillary Chute, “Comics as Literature? Reading Graphic Narrative,” PMLA 123 (2008): 462. Chute argues that in graphic narratives “we see [. . .] a rigorous, experimental attention to form as a mode of political intervention” (426).

9. Neoliberalism is broadly defined as a system of practices that breaks with the Keynesian model of state intervention and social welfare programs and seeks to bring all aspects of life under private, market-driven control.

10. Jeff Ferrell, “Remapping the City: Public Identity, Cultural Space, and Social Justice,” Contemporary Justice Review 4.2 (2001): 167.

11. John R. Logan and Harvey Molotch, Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy of Place (Berkeley: California University Press, 1987), 13.

12. Neil Smith, The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City (London: Routledge, 1996), 6.

13. David Wilson and Dennis Grammenos, “Gentrification, Discourse, and the Body: Chicago’s Humboldt Park,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 23.2 (2005): 300.

14. Ibid., 301.

15. Marisa Alicea, “Cuando nosotros viviamos . . . : Stories of Displacement and Settlement in Puerto Rican Chicago,” CENTRO Journal 13.2 (2001): 167–68.

16. Rachel Rinaldo, “Space of resistance: The Puerto Rican Cultural Center and Humboldt Park,” Cultural Critique 50 (2002): 135–74. Although Ware does not include the displacement of Puerto Rican families in the strip, the disruption of Humboldt’s tight-knit Puerto Rican community, as documented by Rinaldo and others, has transformed the area into a potent signifier for the gentrification of Chicago’s urban neighborhoods.

17. This is not to suggest that Ware has completely avoided overtly commenting on the connection between urban space and race. In his ACME Novelty Library, in a parody of the advertisements found in the back of comic books, he advertises “LARGE NEGRO STORAGE BOXES” that can be purchased for $5,000,000. “Designed by famous European craftsmen,” he writes, these boxes “are just the thing to keep unsightly Negroes out from under foot and to make sure that your city continues to run cleanly and efficiently.” Chris Ware, The ACME Novelty Library Final Report to Shareholders and Saturday Afternoon Rainy Day Fun Book (New York: Pantheon, 2005), 62.

18. Max Page, The Creative Destruction of Manhattan, 1900–1940 (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1999), 10.

19. Ibid., 5.

20. Smith, “New Globalism, New Urbanism: Gentrification as Global Urban Strategy,” Antipode 34.3 (2002): 435.

21. Page, The Creative Destruction of Manhattan, 3.

22. Logan and Molotch, Urban Fortunes, 2.

23. Ibid.

24. Gordon MacLeod, Mike Raco, and Kevin Ward, “Negotiating the Contemporary City: Introduction,” Urban Studies 40 (2003): 1659.

25. Michael Jager, “Class Definition and the Esthetics of Gentrification: Victoriana in Melbourne,” in Gentrification of the City, ed. Neil Smith and Peter Williams (Boston: Allen and Unwin, 1986), 83.

26. Chris Ware, “Building Stories,” nytimes.com, April 9, 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/packages/pdf/magazine/20050918funny.pdf (accessed April 20, 2006).

27. Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Vintage, 1992), 187.

28. Ibid., 4.

29. Lewis Hyde, The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property (New York: Random House, 1983), 22.

30. Writing about the need for old buildings, for instance, Jacobs notes that “the unformalized feeders of the arts” such as studios and galleries “go into old buildings.” Further, she writes, “As for the really new ideas of any kind—no matter how ultimately profitable or otherwise successful some of them might prove to be—there is no leeway for such chancy trial, error and experimentation in the high-overhead economy [. . .] Old ideas can sometimes use new buildings. New ideas must use old buildings.” Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 188.

31. Ironically, Jacobs’s ideas about city life have been adopted by individuals and groups known as New Urbanists who seek to construct versions of traditional urban neighborhoods out of inner-city neighborhoods. According to Jacobs, such plans don’t have a “sense of the anatomy of [the] hearts” of cities. Further still, critics have charged New Urbanists with “romanticiz[ing] her vision, bastardizing her empirical observations of how cities work into a formula they want to impose [. . .] on cities.” Bill Steigerwald, “City Views: Urban Studies Legend Jane Jacobs on Gentrification, the New Urbanism, and Her Legacy,” Reason.com, June 2001, http://www.reason.com/news/show/28053.html (accessed February 12, 2008).

32. David Ley, “Artists, Aestheticisation and the Field of Gentrification,” Urban Studies 40 (2003): 2528, 2536.

33. Herbert Schiller, Culture, Inc.: The Corporate Takeover of Public Expression (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 102. Schiller writes that as “the condominium, boutique, [and] expensive restaurant scene [. . .] flourish[es] in the downtowns of many American cities [ . . . t]he urban poor are removed to the city’s fringes, while the most helpless and desperate roam the streets and huddle in darkened doorways” (102).

34. Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, 188.

35. Philippe Aries, “The Family and the City,” Daedalus 106.2 (1977): 233.

36. Michael Sorkin, “Introduction,” in Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space, ed. Michael Sorkin (New York: Noonday, 1992), viii.

37. Ibid.

38. Angela Miller, “Introduction,” in Strips, Toons, and Bluesies, ed. D. B. Dowd and Todd Hignite (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2004), 6.