To go fast is to forget fast, to retain only the information that is useful afterwards, as in “rapid reading.” But writing and reading which advance backwards in the direction of the unknown thing “within” are slow. One loses one’s time seeking time lost. —Jean-François Lyotard, The Inhuman: Reflections on Time

In The Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin gives a vivid impression of how strollers moved in the shopping arcades of nineteenth-century cities: some of them, he notes, walked with a tortoise on a lead.1 These flâneurs not only cultivated slowness deliberately, but they ensured that others took note of the fact in order to express their contempt for the machine age and its obsession with speed. Benjamin’s image conjures up a type of person almost unthinkable today, but one that perfectly matches the tenor and rhythm of Chris Ware’s comics. Ware’s graphic novel Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth proceeds in small increments on the micro level of its individual panels, in which characters take dazzlingly small steps.2 In a literal sense, this can be explained by the fact that Jimmy Corrigan suffers from a leg wound that forces him to use a crutch and prevents him from moving at normal speed. The implication, however, especially in terms of the text’s layout and composition, is that the modern mechanization of time has reduced our lives to a series of small units that can no longer be experienced as a whole. Indeed, the formal grammar of Ware’s comics renders time conspicuous, inscribing forms of temporal progression (or speed) in its graphic representation. It also calls attention to controlled pace as, among other things, an obstacle to the frenetic temporality of contemporary consumer culture. In an interview, Ware acknowledges his interest in “the craftsmanship and care and humility of design and artifacts” from earlier eras, explaining his preference as a reactionary response to the rhythm of modern experience: “It seems [there is] this arrogant sexuality to the modern world that I find very annoying, and, I guess, threatening [. . .] Everything has to be cool. Everything has to be sexy and fast-paced and rock-and-roll and I just find it kind of offensive. There seems to be a sort of dignity to the way we were creating the world a hundred years ago that I find much more comforting.”3 Ware’s response to these rhythms is shaped by two competing yet related forms of disrupted temporality—incrementalism and fragmentation. While these do not function identically, they converge to generate narrative slowness and critique modern practices of acceleration.

Few graphic narratives resist this fast-paced, rock-and-roll aesthetic as effectively as Jimmy Corrigan. No doubt, the formal difficulties of Ware’s earlier works also present a formidable challenge to these assumptions. Yet the awkward, labor-intensive rhythms of the graphic novel delay and retrack narrative development, waylaying readers with constant interruptions and slowing their progression. In a brief analysis of Ware aptly entitled “Why Does Chris Ware Hate Fun?” Douglas Wolk remarks that “Ware forces his readers to watch his characters sicken and die slowly, torment (and be humiliated in turn by) their broken families, and lead lives of failure and loneliness.”4 My own analysis focuses on the first part of this assessment—the slow decay and death—which is key to understanding the embarrassment and isolation that Wolk mentions. A reading of slowness in Ware’s comics would not only give a new cast to what we consider to be the speed of comics as a medium, or the rhythm of its unique language, but also establish the slowness of graphic narrative as an essential parameter of making and reading comics. The process of drawing the comics, as described by Ware, entails “about an hour and a half of work per second of reading time.”5 This exceedingly meticulous creative process inevitably results in comics that may indeed be read very quickly but more often than not invite an equally painstaking approach on several temporal levels.

This essay draws attention to the intensive and extensive forms of temporality in graphic representation, in particular, to the obsessively uncomfortable slower-than-real time in which the Jimmy Corrigan narrative plays out, with a focus on the agonizing patience and misery of the protagonist’s embarrassment as an existential and profoundly temporal leitmotif. I start from the premise that narrative time shrinks or dilates according to the emotional state of the protagonist, who thus dictates the pace of the story. As Thomas Bredehoft has argued, “the architecture of narration” is derived from “the structural practice in comics of using space to represent time.”6 While Bredehoft details how narration in Jimmy Corrigan breaks the linearity of a time-sequenced narrative line (especially through the intrusion of three-dimensionality in the novel’s cut-out games), I investigate what happens not only when the text formally disrupts time-sequencing, but when the narrative speed of events is inflected by patterns of constructed and contingent emotion. Therefore, I am less interested in the multiple levels created by the composition of the book as a whole than in the subtler juxtapositions within individual panels and their saturation of affect, resulting in a viscous sense of chronology. In brief, I want to show that Ware’s preoccupation with temporality revolves around the concepts of nostalgia, repetition, and non-hierarchical (or, according to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, rhizomatic) structures. At the same time, the nostalgia and slowness invoked by the narrative are paradoxically informed by technologies of speed and interconnection that Ware makes a point of criticizing both overtly and through the subtle pacing of his narrative plot.

Accelerated temporality has become, as the French cultural theorist Paul Virilio has argued, the defining characteristic of our times, one that is beginning to cause anxiety as a result of the “general impression of powerlessness and incoherence” it creates, along with a fragmentation of perception and consciousness.7 In developing his theory of “dromology” (or the logic of speed), Virilio engages with and criticizes the impact of acceleration on contemporary society, in terms of our perception of space, distance, mobility, and technology.8 Virilio’s pessimistic observations can be placed into a longer history of modernist thinking about the energizing and exhilarating (as in Futurism) or nefarious consequences of acceleration. Foregrounding slowness is a feature of much avant-garde work of the mid-twentieth century as well as a marker of minimalist aesthetics. Some modernist authors, Samuel Beckett and Gertrude Stein among them, pose challenges to clear-cut distinctions between fast and slow, as the repetitive features in their works clearly disturb the alternation of slowness and speed. Alain Robbe-Grillet’s nouveau roman Jealousy (La Jalousie) offers a classic example of structural slowness by following the surveillant activities of a husband silently observing his wife’s suspected affair with another man. In her study of the temporal and experiential anxieties of modernity, especially in connection with the visual arts, French philosopher Sylviane Agacinski diagnoses a tendency in modern culture toward “an experience of passage and of the passing, of movement and of the ephemeral, of fluctuation and of the mortal,” which renounces conventional forms of historical temporality. To Agacinski, “modern temporality is the endless interlacing of the irreversible and the repetitive.”9 In this sense, reading Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan is sometimes akin to watching time pass, while Jimmy himself becomes what Agacinski innovatively calls a “passeur de temps”—a passer of time.

Despite this rampant proliferation of speed in the modern world and literary interrogations of the phenomenon, narrative slowness as a concept is almost completely free of institutionally entrenched definitions. In fact, it is impossible to probe ideas of slowness without paying close attention to its governing concept, that of speed, which in turn has been a highly under-theorized issue of narrative theory. Although there are, of course, multiple theoretical perspectives on the function of meter and rhythm in literary texts, these approaches focus primarily on the textual poetics of the cadence, the beat, and the poetic “voice” or tone, seen structurally rather than thematically. Moreover, they also do not cover the range of intermedial relations that can be found in the comics genre, premised as it is on a fundamental interaction between the image and the text, which requires a different perspective on the reading process.10 As a decisive quality of any text, speed often leads primarily to qualitative assessments of a narrative’s “too slow” pace. Research on the subtler effects of textual speed remains scarce and heterogeneous, focusing not only on structural but also, and with mixed results, on thematic temporality, i.e., a text’s preoccupation with issues of acceleration and deceleration. While Kathryn Hume eloquently elaborates modes of textual and thematic acceleration in novels, she mentions “narrative retardation,” a concept proposed by Russian formalist Victor Shklovsky, only in passing.11 Shklovsky’s device of “retardation” refers to a set of digressions that slow down the reader’s perception of a certain narrative progression, exemplified by the critic in reference to Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy.12 This particular theory foregrounds such decelerating techniques as digression, defamiliarization, repetition, and narrative embedding, also mentioning characters as a means to this end, a point that I will return to in my analysis of narrative delay tactics in Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan.

Temporality is also acknowledged as an essential component in comics, a medium generally defined as “a hybrid word-and-image form in which two narrative tracks, one verbal and one visual, register temporality spatially.”13 As Art Spiegelman notes, comics “choreograph and shape time” through their interplay of words and images, although little has been made so far of the potential differences between the velocity of conventional reading and the imperative to both see and read within the comics genre.14 In this particular medium, slowness is characterized by complex visual and typographic means of manipulating rhythm by decelerating the average tempo of a comics narrative. The latter tends to be fairly brisk, if merely as a result of the word-image juxtaposition training the reader’s eye to skip from one to another at a quick pace.

Ware, on the other hand, has displayed an intense preoccupation with the disruption of a conventional reading pace, and its attendant spatial manifestations, in his comics. His techniques range from dividing a panoramic page into polyptychs that chart several different units of time—a method Ware first encountered in Frank King’s Gasoline Alley—to temporal overlaps and methods of stalling narrative progression.15 Already in his early silent strips, Ware considered the implications of purely visual storytelling. On the one hand, the lack of visual detail in these strips seems to allow the reader to traverse the narrative stages with considerable swiftness and ease. Ware even suggests an analogy between his comics and early animation by referring to two one-page strips featuring Quimby the Mouse as “comictoons.”16 Commenting on the speed of Ware’s Quimby strips, often subdivided into crunched-up, barely visible slivers, Wolk remarks: “If comics are ‘a pictographic language,’ as Ware says, then they’re meant to be read fast. Dominated by simple shapes and ‘dead,’ fixed-width lines, Ware’s pages zoom along, slowed down only by tricky diagrammatic layouts and occasional indigestible blocks of tiny type.”17 On the other hand, what Wolk fails to acknowledge is that the more formal, diagrammatic aspects of the panels demand increased attention, thus posing some problems for plot-driven readers. By repeatedly attempting to visually revert to childhood through the invocation of dated cultural paradigms, Quimby also instantiates a desire to not only reinhabit the past but reconstruct it from scraps of memory as well. In its combination of mourning and melancholia, this mood corresponds to what media artist and novelist Svetlana Boym terms “reflective nostalgia,” which “dwells in algia, in longing and loss, the imperfect process of remembrance [. . .] lingers on ruins, the patina of time and history, in the dreams of another place and another time.”18

Ware’s later works, especially Jimmy Corrigan, with its subtext of loneliness and mortality, are easier to linger over in a way that Quimby’s pictographic simplicity resists. For one thing, the graphic novel is almost entirely unpaginated, which flouts established conventions of sequential narrative. Secondly, it contains diagrams retelling personal histories that replicate the non-linear, open-ended, associative clusters of memory itself.19 Narrative deceleration is also achieved by placing recurrent images and motifs on different pages, thus sending the eye back to a previous narrative stage and preventing events from spiraling out of the careful reader’s visual control.

Many of Chris Ware’s comics show an interest in the passage of time from the perspective of obsolescence and nostalgia, both in cultural and human terms. What one interviewer has referred to as Ware’s “astringent melancholia” is a recurrent trope that spans most of Ware’s oeuvre as a self-described attempt to “tell something much more slowly and blurrily, the way real life tends to evolve.”20 This melancholic streak is particularly visible in Jimmy Corrigan’s double journey back in time. On one level, Jimmy attempts to recover his absentee father and, implicitly, that part of his childhood that was harmed by his abandonment. On a second narrative plane, Jimmy’s grandfather recounts his own miserable childhood in the 1890s. Moreover, behind Jimmy’s inability to interact with the world lies a hyperactive fantasy life that transports both character and reader toward the past, while undermining Jimmy’s ability to cope with mundane situations in the present. Meeting his long-lost father reveals Jimmy’s own status as an emotionally truncated figure inhabiting a past of his own devising, one that he delights in refurbishing, even as he takes imaginary swipes at present realities that he never dares to criticize out loud. In one scene, Jimmy imaginatively revisits the setting of his own conception and carries out a very oedipal revenge against his father by bludgeoning and cutting him with a beer stein. Another shows Jimmy’s grandfather being thrown from the observatory of “the largest building in the world”—a scene that, we are told, “only finds its way into the recurrent and abbreviated symbology” of the grandfather’s dreams (279–80).

In Jimmy Corrigan, however, time stops and seems to spill not only backwards, as the story revisits previous events, but also sideways, as alternative narratives are incorporated into the main story line. From this wayward temporal flux, meanings emerge in slow motion and underfed, sluggish emotions crystallize. Importantly, the essentially self-destructive tenor of Jimmy Corrigan is caused not only by Jimmy’s penchant for daydreaming but also by the impossibility or refusal to look further than the present. In other words, although his attitude is nostalgic, he also lapses into deep melancholia, which is less focused on past joys or possessions, instilling a fundamental passivity and reluctance to focus on the future. Jimmy’s tragic inwardness, then, results from a sense of temporal immobility in terms of both narrative and character, which is also replicated compositionally. Numerous pages in the book depict the protagonist from the same perspective (often from outside the building he inhabits, through a window), which can recur over as many as nine panels (18). Other pages are organized around a central panel that shows the exterior of the space where the plot is unfolding, usually a peaceful, un-populated image obscured by darkness or inclement weather (195–96, 198). Such expository or transitional stills often crop up unexpectedly, i.e., on the left rather than the right-hand side, so they can only be seen once the page has been turned, thus effecting an abrupt transfer into another segment of the story (199, 337).

Many of these silent panels are almost identical, reinforcing the idea of a past that recurs with obsessive persistence. The constant replay of memories, often encapsulated in iconographical detail, epitomizes the concept of difference through repetition suggested by Gilles Deleuze.21 Drawing on Freud, Deleuze claims that with repetition comes not only difference—understood within the repetitive pattern in which it is concealed—but also remembrance. These two features aptly describe the circular movements in many of Ware’s narratives and repetitive (in- and out-zooming) panels. Often the narrative events seem to emerge from a pool of unconscious links and memories, very much in keeping with Deleuze’s description of repetition as “the unconscious of representation.”22 Additionally, the repetition involved in patterns of compulsive memory as well as the recurrence of certain elements of visual style recall the practice of collecting, the essence of which is an interplay between repetition (the accumulation of objects related to one theme) and difference (they are not identical). The composition of the panels on the page also mimics an act of collecting by creating an imaginary present in which the narrative levels communicate one to one rather than in progression, all characters following the slow script of a fictive contemporaneity, in which they interact like so many recycled childhood icons.

In keeping with his dictum, borrowed from Goethe, that “architecture is frozen music,” Ware freezes his panels in architectural stills that stall narrative progression.23 At the same time, he creates inner spaces of temporal layering within the panel itself, thus deepening the temporal involvement with each panel and slowing down the reading process. A paradigm of this technique is the temporal overlap occasioned by Jimmy’s daydreams as he and his stepsister Amy meet the doctor to discuss their father’s condition after his car accident. To Jimmy’s consternation, his mother appears in eight panels of his interior thoughts, trying to gain Jimmy’s sympathy, while referring to Amy as a “colored girl” and expressing her disapproval (307–8). More generally, Jimmy’s self-absorbed mother—living in a nursing home from where she incessantly calls her son at work and at home—can be considered a constant obstacle to narrative progression. This is due not only to her repeated and often unexpected appearances, but especially to her function as an emotional leash for Jimmy himself, merely diverting attention from whatever it is that her son is (not) doing. At the same time, by serving as a frame for the novel as a whole, she can be said to contain the narrative, which she occasionally interrupts, shadowing her son like a malevolent doppelgänger.

Not only are Jimmy’s temporal bearings destabilized by the encounters with his mother, but the narrative itself is temporally dispersed and scattered in a heterogeneous fashion; in this sense, it resembles a postmodern approach to form. In its structure, if not in its thematic concerns, Jimmy Corrigan recalls the de-temporalized simultaneity of the rhizome-concept as articulated by Deleuze and Guattari in A Thousand Plateaus as well as by hypertext as a mode of sequential and parallel differentiation.24 Working from Deleuze and Guattari, Stuart Moulthrop describes the rhizomatic structure of discourse as “a chaotically distributed network [. . .] rather than a regular hierarchy of trunk and branches”—not a deterministic chain of beginnings and ends, but the organic growth of an absolute “middle.”25 In this system, any point may be connected to any other point. Ware’s comics resemble this model of connectivity in the allusive form of its non-linear, boundary-less narrativity that lacks temporal finitude and closure. The most explicit illustrations of this fragmented, non-hierarchical textuality can be found in the diagrams that chart characters’ family backgrounds and life stories in minute pictorial forms. These can be read both from left to right and vice versa, often providing directions in the form of arrows very much like digital linking icons.26 Despite Ware’s impatience with contemporary modes of mechanical reproduction, the temporal and conceptual framework of digital media has clearly seeped into the fabric and structure of his comics.

It is thus paradoxical that Ware’s work should be influenced by the very technologies he set out to denounce through his insistence on the deceleration of perception. On the one hand, the entire corpus of Ware’s work can be read as a critique of contemporary capitalist technology that demands an ever-growing reliance on speed and temporal acceleration, on the “sexy” aesthetics of fast-paced rock and roll. On the other hand, Ware’s own technologies of drawing, by mere dint of their fastidiousness, acquire the comprehensiveness and connectivity of technological devices which are indeed essential to the reproduction and distribution of his work. In fact, a Web version of the Corrigan family tree is also available online.27 What sets his work apart from digital design, however, is the intractable materiality of the medium as an object than can be seen, held, toyed with, and finally collected. With Jimmy Corrigan, the artist’s insistence on the materiality of the book as artifact as well as the often circular paths of his narratives also reflect his criticism of the increasing incrementalism and serialization of the artistic world—despite the fact that many of Ware’s other works are multiply serialized. Ware’s insistence on deceleration in Jimmy Corrigan not only defends the freedom of art from technological temporality, but reminds us of the small, un-dromological steps we take in our daily lives as well.

In short, exhilaration and speed are not prominent features of Chris Ware’s output in the comics medium. In addition, rather than paring away unnecessary words and employing the kind of telegraphic style that would allow readers to navigate easily through the visuals, Ware is in the habit of pairing the images with an equally sophisticated, multi-layered text, to the point of sounding verbose. Here is, for example, the rather unlikely monologue by Jimmy’s grandfather, as he recalls his visit to the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893: “One’s memory, however, likes to play tricks, after years of cold storage. Some recollections remain as fresh as the moment they were minted while others seem to crumble into bits, dusting their neighbours with a contaminating rot of uncertainty” (276). Such puzzling metaphors only serve to further obfuscate both the memories and the narrative that binds them. “To get speed,” Hume writes, “we need to feel that we are missing out on meaningful transitions and links.”28 Ware offers little in the way of such subtracting techniques. On the contrary, what he favors is an excess of narrative connectivity, particularly in terms of iconography and other descriptive devices and linkages that stabilize fictional reality and prevent reading from speeding along too quickly.

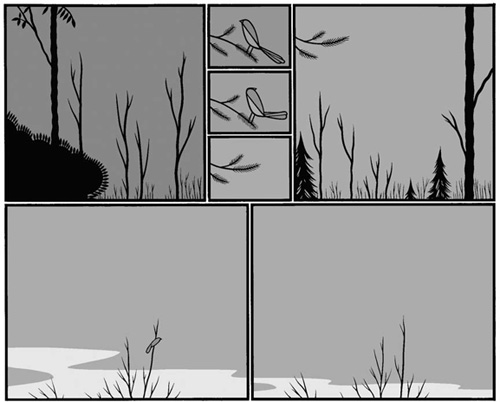

Fig. 13.1. The iconography of slowness. Silent panels provide moments of narrative respite. Chris Ware, Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth (New York: Pantheon, 2000), 99.

“Jimmy Corrigan’s themes,” Thomas Bredehoft writes in his study of architectural multilinearity in Ware’s work, “include not only the passing of time and the recurrence or circularity of events within the passage of time, but also endurance and lack of change as well.”29 These features often translate into panels that halt the flow of narrative time. After Jimmy is hit by a truck and lies on the ground, the page following the accident scene contains seven panels of unequal sizes depicting bare tree branches, a bird that appears in three of the panels, a clear sky—alternately blue and gray—a hint of cloud, haze, or water in the bottom panels and nothing else (see fig. 13.1). The last panel, designed like a postcard, includes the words “A chill morning in April” (99). Jimmy Corrigan contains many such quiet moments that allow Ware to break the linearity of a time-sequenced narrative. Some resemble the iconography of still photography; others can be compared to pre-projection film, registering only slight modifications from one panel to the next and slowing down or almost completely impairing the process of reading.30 This shock of silence leaves the reader reeling on the fault line where events occur abruptly, thus reproducing and performing the sudden changes that take place in Jimmy Corrigan’s narrative and the protagonist’s own shock after being struck by the vehicle. Moreover, while static, these panels travel, as it were, across the book’s multiple sections, punctuating the narrative and performing an integrative function through their conspicuous recurrence.

However effective on a first reading, the impact of these silent, repetitive panels is unlikely to endure when one rereads. What the reader encountered prior to these panels affects the way the visually coded rhythm effects are experienced, and the surprise element will fade with familiarity. Hume also remarks on how narrative acceleration and the confusion it engenders wear thin on second reading: “The speed effect operates best during one’s first reading, but loses its ability to bother us as much on subsequent readings. The politics of using narrative speed are thus relatively ephemeral.”31 In generating narrative slowness, however, Ware’s slow motion panels in fact mask a second reading taking place concurrently with the first. As Matei Calinescu has shown in his study of (re)reading practices, when a reader experiences the text with increased “structural attention,” even a first-time perusal can have the same effect as a “second” reading.32 These panels intensify reader participation and focus our attention to the extent that the pause they introduce allows the reader to revisit what came before and re-evaluate her own expectations.

It is also interesting to note that the slow moments, in fact, cover only brief periods of time with panels in succession at one-second intervals, or stretching over long minutes rather than long days—the duration residing in our subjective perception rather than in the actual number of panels we are perceiving.33 One six-panel page, for instance, made up of two tiers of two and four panels, respectively, includes four successive images of the same red phone (framed by a window) and a drop of rain falling onto the window sill (see plate 16). The downward trajectory of the raindrop is rendered over three panels, each of which thus contains a unit of time less than one second in length. At other times the duration of a sequence is determined by Ware’s efforts to “indicate hidden emotions by the order of expressions” on the characters’ faces and in their awkward body language, which in turn derives from extremes of embarrassment or hesitation.34 After his stepsister Amy rejects his offer of sympathy on hearing that their father has died, Jimmy leaves the hospital in slow motion, each panel marking one step he is taking toward the door (350). More than a reaction to the unfortunate situation, Jimmy’s lumbering movement is the expression of a deeper despondency, whose very depth can only be visualized by designing the panels to accommodate depth of field. Rather than interrupting the narrative, such sequences engender a sense of suspense, demanding greater reader participation through their elusive mood and indeterminate outcome.

Recurrences within the silent panels, such as the small red or gray bird carrying a twig or flower, sitting on a tree branch (4, 5, 99, 102–4, 251, 338), serve as an element of continuity. Despite their stillness, they convey implicit motion from one panel to the next and often mark radical time shifts from one episode to another. Moreover, the homogeneous color scheme (dark browns, blues, grays) not only gauges the grimness of Jimmy’s story, but also provides internal visual continuity by linking panels that lack a formal sense of sequence. In such instances, the links between successive panels are important as they trigger the reader’s automatic reaction of comparing the elements included on each page. In other cases the deferral of signification from one panel to the next has no role in the formation of narrative (i.e., sequential) meaning. This, however, also does not mean that the panels are interchangeable or could establish free and fortuitous connections among themselves. Rather, a blockage occurs in what Jacques Derrida (a figure mocked by Ware in The ACME Report) and subsequent poststructuralists have termed différance.35 To put it simply, the term denotes the postponement of meaning from one signifier to the next along the endless chain of a process that does not terminate in any one final or established signification, but allows meaning to take shape from linkages and deferrals.36

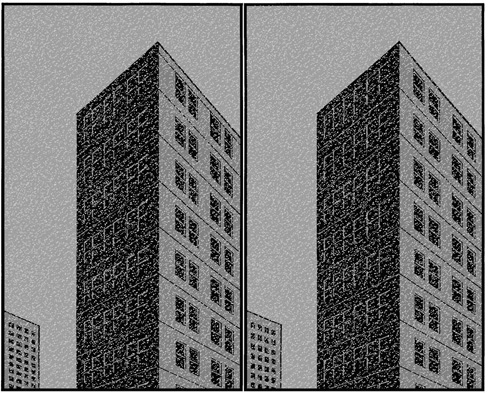

Fig. 13.2. A narratological and emotional cul-de-sac. The panels are almost visually identical, but their spatial succession sets them apart. Chris Ware, Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth (New York: Pantheon, 2000), 362.

Ware’s techniques amount to what we could playfully call “in-différance,” to the point where one image is indistinguishable from the next and the narrative progression derives from the two panels’ lack of difference in the context of their spatial alignment. In other words, Ware shows that narrative can be constructed not only through an excess of connectivity and signification, but also by containing meaning, at the risk of defying the formal conventions of the medium itself. Consider, for example, the last two pages before the epilogue, each containing two panels that follow Jimmy’s progress from the train station to his office building (see fig. 13.2). Emotionally, he is traversing a critical time: his long-lost and then regained father is now dead; his stepsister violently pushed him away; he is alone, disappointed, somewhat baffled by the turn of events; outside it is snowing heavily and thick snow is carpeting the ground. The high rise he is heading toward appears in all four panels. If the second panel contains slight modifications compared to the first, the difference between the third and forth panels is so microscopic as to be almost unrecognizable (361–62). Although the panels continue to be separated by a gutter, the reader can no longer project causality into this spacing. As still, encapsulated moments, the panels themselves come to resemble a sort of gutter interposed between the story and its ending, preparing the reader for its emotional impact. Even if the silent panels reveal the extent to which Ware redefines temporal linkages on the micro level of individual pages, on the macro level of the novel the narrative denouement is not suspended but merely postponed. Paradoxically enough, by decelerating the narrative and delaying its resolution, Ware only increases its inevitability.

As I mentioned earlier, the duration of Jimmy Corrigan’s temporal sequences is often determined by the intensity of a particular mood or feeling that subjectively inflects the perception of time. “I rarely ever did a comic just for the sake of experimentation,” Ware writes. “Even when I did, I was always trying to get at some kind of feeling.”37 Not only does Ware express slowness by encoding it into the composition of his comic strips, but he uses these narrative breaking points to deliberately provoke reader anxiety in order to reveal the underlying causes for this stress. What emerges from both the slowness of his larger narratives and that of their individual panels is a fear of slowness which encroaches upon the readers themselves. While meticulous slowness was a shorthand for leisurely lifestyle in the Parisian arcades of the nineteenth century, here slowness seems to indicate nothing but trauma.

The affective structure of Ware’s work is closely bound up with the immediate intimacy between the text and those who interact with it, both in writing and reading comics; as he writes in his introduction to McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern 13, “unlike prose writing, the strange process of writing with pictures encourages associations and recollections to accumulate literally in front of the eyes; people, places, and events appear out of nowhere. Doors open into rooms remembered from childhood, faces form into dead relatives, and distant loves appear, almost magically, on the page—all deceptively manageable, visceral, the combinations sometimes even revelatory.”38 The self-contained visions in the still panels discussed above are “revelatory” in that they communicate a sense of personal anguish or confusion. Not only can these feelings, prompted by memories and nostalgia, produce narrative delay, but they can also be the cause of slowness obtained by other means. Narrative deceleration in general can be said to reflect varied emotional states, ranging from fear and distress to embarrassment and boredom. Jimmy is remarkable for his extreme sensitivity, a characteristic that Ware stresses and even amplifies by manipulating narrative progression. It can be the embarrassment of a particular predicament, such as accidentally spilling the container of urine needed for a medical examination in the aftermath of his accident, or it can be the nurse’s inadvertent infliction of embarrassment (she all too gladly overlooks his clumsiness, which provokes his erotic fantasies), either by cruel malice or as affectionate therapy. In both cases the slow pace of the narrative is complicit with Jimmy’s own self-consciousness, shyness, and shame.

As a recurrent trope of early child development that fosters a sense of both individuality and relationality, shame not only has become a thematic mainstay of comics—employed to great effect in, among other works, McSweeney’s 13, edited by Chris Ware—but also has been regarded as a heuristic for, in Daniel Worden’s words, “how comics constitute themselves as an art form that perpetually effaces itself when claiming status as art.”39 Many of Ware’s works can be read as permutations on the single theme of human alienation and shame. Further variations on these emotions stem from whether Jimmy himself undergoes the affective event or whether the reader’s own mind is targeted. The perspective shift from protagonist to reader is usually enacted by substituting the first person for third person in the visual narration. For instance, Ware shows Jimmy attempting to murder his father without diegetically signposting this deviation from the main story. A means of staving off his embarrassment would be to incite himself to indignation, but this only occurs in his imagination. Far from appearing sentimental, Jimmy Corrigan thus depicts little in the way of emotion—explicit visual hints to affective states are few and far between—but goes a long way toward creating it. Ware suggests that the speed of reading in itself determines the text’s affective content: “The mood of a comic strip did not have to come from the drawing or the words. You got the mood not from looking at the strip, or from reading the words, but from the act of reading it. The emotion came from the way the story itself was structured.”40 In other words, affect does not reside in Jimmy’s defenselessness in the face of the unfortunate events, but in the narrative intensity created by the prolonged display of his reactions, often in images that do not feature the protagonist but suggest the emptiness of his mood.

I suggested at the outset that beyond Chris Ware’s tendency to spatially juxtapose past, present, and future moments on a single page (or even within a single panel), his highly textured comics also engage in a complex strategy of determining narrative speed by structural and compositional means. The effects of these techniques are often paradoxical. Ware toys with narrative expectations of temporal movement by drawing panels that give the readers pause and quicken their pulse at the same time. The narrator of these multiply temporal strips is simultaneously immersed in time and assembling time. He communicates a perception not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence. He addresses time’s passage with an implicit (and structural) nostalgia. In fact, Jimmy Corrigan’s uprooting—from his family, social networks, and emotional connections—is so profound that he is not even aware of it, to the point where his nostalgia slowly morphs into a pervasive melancholia. The slowness of his existence is translated by Ware into narrative techniques of both continuity (mundane objects that anchor him down) and discontinuity (the absentmindedness of his reveries). At the heart of Jimmy’s lack of engagement with the world lies, however, an abiding fear—of the female coworker whom he never dares to woo openly, of his stepsister whom he fantasizes about, of his absent father and overbearing mother—which Ware deftly translates into multiple deferrals and repetitions, as his narrative falters and questions its own drive, obstructing a quick purchase on its meaning. Ware’s use of slowness thus proves to be less an external approach to narrative and more of an intrinsic function of the writing process, of memory, of the text’s own affective unconscious that collects the emotions of both characters and readers. Considering his very limited narrative agency, Jimmy may not be, after all, a “passer of time,” despite his openness to time and its potentialities. Above all, his is a consciousness through which time passes, leaving him to inch his way out of emotional and temporal captivity, in a struggle that is both hopeless and empowering.

1. Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 422.

2. Chris Ware, Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth (New York: Pantheon, 2000). All further references to this text will be indicated in parentheses.

3. Chris Ware, qtd. in Andrew Arnold, “Q and A with Comicbook Master Chris Ware,” TIME, September 1, 2000, http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,53887,00.html (accessed February 25, 2009).

4. Douglas Wolk, Reading Comics: How Graphic Novels Work and What They Mean (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2007), 347. Wolk does not elaborate theoretically on Ware’s use of slowness, limiting his interpretation to the masochistic function of prolonged embarrassment and emotional frustration.

5. Keith Phipps, “Interview with Chris Ware,” The Onion A.V. Club, December 31, 2003, http://www.avclub.com/articles/chris-ware,13849/ (accessed February 25, 2009).

6. Thomas A. Bredehoft, “Comics Architecture, Multidimensionality, and Time: Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth,” Modern Fiction Studies 52 (2006): 870–71.

7. Paul Virilio, The Original Accident, trans. Julie Rose (Cambridge: Polity, 2007), 4.

8. See Paul Virilio, Speed and Politics: An Essay on Dromology (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986).

9. Sylviane Agacinski, Time Passing: Modernity and Nostalgia, trans. Jody Gladding (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 11, 12.

10. For a rare overview of this untapped field see Kathryn Hume, “Narrative Speed in Contemporary Fiction,” Narrative 13 (2005): 105–24; Jan Baetens and Kathryn Hume, “Speed, Rhythm, Movement: A Dialogue on K. Hume’s Article ‘Narrative Speed,’” Narrative 14 (2006): 349–55.

11. Hume, “Narrative Speed,” 106.

12. Victor Shklovsky, “Sterne’s Tristram Shandy: Stylistic Commentary,” in Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays, intro. Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reis (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965), 25–60.

13. Hillary Chute, “Comics as Literature? Reading Graphic Narrative,” PMLA 123 (2008): 452.

14. Art Spiegelman, “Ephemera vs. the Apocalypse,” Indy Magazine (autumn 2005), http://64.23.98.142/indy/autumn_2004/spiegelman_ephemera/index.html (accessed July 13, 2008).

15. See Daniel Raeburn, Chris Ware (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 13.

16. Chris Ware, Quimby the Mouse (Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2003), 46–47.

17. Wolk, Reading Comics, 355.

18. Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic, 2001), 41. The opposite term is “restorative nostalgia,” which is bent on rebuilding the lost home and patching up memory gaps, a goal more clearly exemplified by Jimmy Corrigan’s journey into the past to meet his father and reclaim a family.

19. For a more detailed analysis of Ware’s treatment of memory in his comics, see Peter Sattler’s essay in this volume.

20. David Thompson, “A Fraternity of Trifles,” Eye Magazine (spring 2002), http://www.eyemagazine.com/review.php?id=62&rid=88 (accessed February 25, 2009); Chris Ware cited in Aida Edemariam, “The Art of Melancholy,” Guardian, October 31, 2005, http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2005/oct/31/comics (accessed February 25, 2009).

21. Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul Patton (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 5, 7, 14.

22. Ibid., 14.

23. Chris Ware, The ACME Novelty Date Book (Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2003), 190.

24. Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massim (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987).

25. Stuart Moulthrop, “Rhizomes and Resistance: Hypertext and the Dreams of a New Culture,” in Hyper/Text/Theory, ed. George P. Landow (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994), 300–301.

26. For a detailed reading of Chris Ware’s use of diagrams, see Isaac Cates’s essay in this volume.

27. See http://www.randomhouse.com/pantheon/graphicnovels/acme.html.

28. Hume, “Narrative Speed in Contemporary Fiction,” 111

29. Bredehoft, “Comics Architecture,” 885.

30. This feature calls to mind Scott McCloud’s remark on the affinities between film and the comics medium: “Before it’s projected, film is just a very very very very slow comic.” Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (New York: Harper, 1993), 8.

31. Hume, “Narrative Speed in Contemporary Fiction,” 107.

32. Matei Calinescu, Rereading (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 51.

33. I use the term “duration” in the sense ascribed to it by Henri Bergson, who uses it to introduce a qualitative concept of time based on subjective experience. Bergson distinguishes between the “empty time” of classical physics and the “experienced time” of consciousness, which is neither measurable nor divisible. See Henri Bergson, An Introduction to Metaphysics, trans. by T. E. Hulme (New York: Macmillan, 1955). See also Jacques Samson, “Une vision furtive de Jimmy Corrigan,” in Poétiques de la bande dessinée, ed. Pierre Fresnault-Deruelle and Jacques Samson (Paris: l’Harmattan, 2007), 221–33.

34. Interview with Gary Groth, “Understanding (Chris Ware’s) Comics,” Comics Journal 200 (1997), 154.

35. A brief strip flippantly questions current theory debates about image potency and its use as a compensatory alternative to failing reading skills: “Who said that the image has lost all power as an aesthetic tool?. . . Was it Lacan, or Daridas (sp?) Or . . . was it that the image was more potent since everyone is so rushed and semi-literate?” Chris Ware, The ACME Novelty Report (New York: Pantheon, 2005), 8.

36. See Jacques Derrida, “Différance,” in Margins of Philosophy, trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982), 3–27.

37. Chris Ware, qtd. in Raeburn, Chris Ware, 11.

38. Chris Ware, introduction to McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern 13 (San Francisco: McSweeney’s, 2004), 12.

39. Daniel Worden, “The Shameful Art: McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, Comics, and the Politics of Affect,” Modern Fiction Studies 52 (2006): 894.

40. Chris Ware, qtd. in Raeburn, Chris Ware, 13.