THIS DOCUMENT IS THE PROPERTY OF HIS BRITANNIC MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT

The circulation of this paper has been strictly limited.

| It is issued for the personal use of . | |

| TOP SECRET |

Copy No. 75

|

J.I.C. (48) 104. (Final)

8th November, 1948.

CHIEFS OF STAFF COMMITTEE.

JOINT INTELLIGENCE COMMITTEE.

SOVIET INTENTIONS AND CAPABILITIES 1949 AND 1956/57.

Report by the Joint Intelligence Committee

.

The U.K. Joint Intelligence Committee and the U.S. Joint Intelligence Committee have jointly prepared an agreed U.K./U.S. Intelligence estimate

*

on Soviet Intentions and Capabilities. Agreement between the two Intelligence Committees has been obtained on all but five points in the estimate, and only two of these, the Soviet campaign in Turkey and the Soviet submarine potential, are important. Where the differences occur, the views of both Joint Intelligence Committees have been included in the estimate. A list of the paragraphs in which these appear is at Appendix to this report.

2. The appreciation is in two parts. Part I

†

covers the period between now and the end of 1949. Part II deals with the period 1956/57. In discussing Part II, it became evident that the U.S. Intelligence Team were principally concerned with the period between now and the end of 1949 and not fully briefed to discuss the period 1956/57. Part II has, therefore, been produced in a more abbreviated form than Part I.

3. The main conclusions in this paper on the strategic intentions of the Soviet Union are in line with those in our paper

‡

“Strategic Intentions of the Soviet Union”, which were not acceptable to the Chiefs of Staff. The Chiefs of Staff held that it would not be within the capacity of the Soviet Government to conduct so many simultaneous campaigns. Although in drafting this section of the paper the views of the Chiefs of Staff on this point were borne in mind throughout, we found ourselves unable to modify our previous views, and we also found that the American Intelligence Team was in agreement with them.

4. It may be that some of our differences are due to faulty presentation of our original paper. We then listed some eight campaigns which we considered likely to be carried out simultaneously. In point of fact there

are only two major campaigns, Western Europe and the Middle East.

It is possible that the Soviet leaders might wish to carry out these two campaigns in succession. They would appreciate, however, that to attack one area first would enable the Anglo-American powers to attack the heart of the Soviet Union from the other. The inescapable conclusion is that in the event of war the Soviet Union would decide to attack both areas simultaneously.

This would also make the best use of the overwhelming superiority of the Soviet Union in land and tactical air forces in the early stages of the war, and would enable her to retain the initiative.

5. If this argument is accepted, the differences between the Joint Intelligence Committee and the Chiefs of Staff would be resolved. The other six simultaneous campaigns are subsidiary or supporting operations employing resources which our intelligence shows are available without interfering with the two main operations.

6. In dealing with our previous papers

*

“Strategic Intentions of the Soviet Union” and “Forecast of World Situation in 1957”, the Chiefs of Staff based their disagreement on the four following arguments:-

(a) Sufficient heed had not been paid to Russian psychology;

(b) All experience went to show that the Soviet Union, unless she was invaded, would limit her strategic objectives;

(c) Russian possibilities were greatly over-estimated and it was doubtful whether 155 Divisions and 1,500 heavy bombers with 20,000 other aircraft in peace time were within the economic capabilities of the Soviet Union, having regard to the immense number of skilled uniformed technicians who would be required to support modern forces of this order;

(d) The Russian command would not be capable of handling several large campaigns at once.

7. Of these arguments, (b) has been considered in paragraphs 3 to 5 above. As regards (a), (c) and (d) our comments are as follows:-

(a) Psychology.

We understand that the Chiefs of Staff mean by this criticism that the Russian mind is likely to be reluctant to fight an offensive war on many fronts outside the territory of the Soviet Union because Russian history shows few examples of such a policy. Present Soviet-foreign policy shows that, at least as regards the “Cold War” the attitude of the Soviet Leaders is different. Furthermore, we believe that, if they become convinced that their aims can only be achieved more rapidly by war, they would provoke it and would hope, by forcing the Anglo-American powers to initiate operations, to persuade the Russian people that they were fighting a defensive war against Capitalist aggression.

(b) Size of the Soviet Air Forces and the Shortage of Skilled Technicians.

The figure 20,000 other aircraft quoted in para 6(c) not only includes the 1,500 heavy bombers already mentioned, but also some 3,000 aircraft of the Civil Air Transport Fleet which, it was thought, might be made available for military duties. We have now agreed with the American Joint Intelligence Committee that the Soviet Air Force contains some 15,000 – 17,000 aircraft, of all types, in operational units and that the establishment of the Civil Air Transport Fleet is of the order of 1,000 – 1,500 medium and 2,000 light transport aircraft. Thus the Soviet Air Force has to provide maintenance backing for some 15,000 – 17,000 front-line aircraft of all types, and not 21,500 as suggested in para 6(c). Further, we believe that the Soviet Union has in its armed forces a relatively smaller number of skilled technicians than the Anglo-American powers. Although the Russians have fewer enlisted technicians than the Anglo-American powers and do not therefore carry out such major repairs within units, their standard of maintenance is adequate. A senior German tank officer has for example reported that in World War II Soviet tank maintenance was good, although bigger repairs were not carried out so fast as in the German Army. The Red Army had plenty of well-trained mechanics and the German Army increasingly employed Russian prisoners of war in their own tank maintenance companies. It is therefore dangerous to assume that lack of mechanical skill would be a source of weakness in their armed forces.

(c) Capabilities of the Russian Command.

During World War II the Russian Command showed considerable ability in handling a number of different operations simultaneously along a front which stretched at one time from the Baltic to the Caucasus. They accomplished this by a system of decentralisation, by grouping armies and supporting air units in “fronts”, and allotting special command teams for specific operations to co-ordinate the action of groups of “fronts”. On the battlefield itself they developed considerable skill in manoeuvring large numbers of armoured formations. They were moreover skilful in moving formations from one area to another and in maintaining the impetus of the advance by ruthless energy in railway construction and operation right into the forward areas. After V.E. day they switched considerable resources to open up a new front in the Far East in accordance with a previously arranged time table. It would be dangerous to assume that the inefficiency resulting from party interference that has been observed in other branches of Soviet life, will also be present in the Army.

8. In reaching our agreed conclusions we have carefully examined the economic

*

and logistic

†

implications. We have concluded that, if the Soviet Union wished to go to war in 1949, economic considerations would not in themselves be enough to prevent her from doing so, if she felt confident of attaining her primary objectives rapidly. Since the biggest campaign, as planned, is not expected to last more than two months, and none more than six months, we consider that the needs of the Soviet forces for military equipment could be met largely from mobilisation reserves. The demands they would make on new production from Soviet industry would therefore not be great.

9. The forces allocated to the main campaigns in 1956/57 do not materially exceed those estimated for the same operations in 1949 except in the case of the attack on Western Europe. For this campaign it is considered that an additional 50 line divisions with supporting air regiments might be required

‡

. Since the total numbers engaged in all the campaigns would still be less than the present strength of the Soviet forces, it is considered that reserves of equipment for these additional 50 line divisions and supporting air regiments would continue to be available. Since the campaigns at the later date are not expected to last any longer than in 1949, the demands on new production would probably be even less than before owing to the additional reserves accumulated during the intervening period of low wastage. During the same period, moreover, a very great increase of production capacity should have taken place in accordance with the planned expansion of Soviet Industry.

10. The agreed view of the British and the U.S. Joint Intelligence Committees as to the intentions of the Soviet Union in a war starting between now and the end of 1949 may be summarised as follows:–

A campaign in Western Europe would be undertaken simultaneously with one designed to seize control of the Middle East (including Greece and Turkey and the Suez Canal area.)

11. It was agreed that these two major campaigns would be accompanied by:–

(a) An aerial bombardment against the British Isles.

(b) A sea and air offensive against Anglo-American sea communications.

(c) A campaign against China, and South Korea, and air and sea operations against Japan and U.S. bases in Alaska and the Pacific, in so far as the Soviet Union can support such operations without prejudice to those in other areas.

(d) Small scale one-way air attacks against the United States and Canada, and possibly small scale two-way air attacks against the Puget Sound area.

(e) Subversive activities and sabotage against Anglo-American interests in all parts of the world, and possibly also by a campaign against Scandinavia and air attacks on Pakistan.

12. It was also agreed that:–

(a) On the successful conclusion of the campaign in Western Europe (and possibly Scandinavia), a full scale sea and air offensive would be directed against the British Isles.

(b) The Soviet Union will have sufficient armed forces to undertake campaigns simultaneously in the theatres mentioned in paragraphs 10 and 11 above, and still have sufficient armed forces to form an adequate reserve.

13. It was also agreed that the Strategic Intentions of the Soviet Union would be substantially the same in the event of war during the period 1956/57.

Recommendations

14. We recommend that the Chiefs of Staff approve this report as a background for further planning and intelligence studies.

15. We further recommend that the J.S.M. Washington should be instructed to seek the comments of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff and to obtain their agreement to the following distribution of this report:–

(c) The Chiefs of Staff in Canada;

(ci) The Commanders-in-Chief, abroad.

(Signed) W.G. HAYTER

E.W.L. LONGLEY-COOK

C.D. PACKARD

L.F. PENDRED

K.W.D. STRONG

P. SILLITOE

D. BRUNT.

Ministry of Defence, S.W.1.

8th November, 1948

TOP SECRET APPENDIX TO

J.I.C. (48) 104

LIST OF PARAGRAPHS IN J.I.C. (48) 100

CONTAINING DIVERGENT VIEWS OF THE U.K. AND U.S. JOINT

INTELLIGENCE COMMITTEES

J.I.C. (48) 104

LIST OF PARAGRAPHS IN J.I.C. (48) 100

CONTAINING DIVERGENT VIEWS OF THE U.K. AND U.S. JOINT

INTELLIGENCE COMMITTEES

New Soviet Naval Units Expected to be Brought into Commission During 1949.

Part I, Appendix “A”, paragraph 29 (e).

Size, Strength, Disposition and Development of Soviet Submarine Force.

Part I, Appendix “A”, paragraphs 49, 118, 160 and 176.

Part II, paragraph 53.

Mobilisation Potential of Soviet Air Force.

Part I, Appendix “A”, paragraph 54.

Soviet Radar Defences.

Part I, Appendix “A”, paragraph 63.

Soviet Campaign in Turkey – Forces Required, Phasing and Timing.

Part I, Appendix “A”, paragraphs 153 and 154.

* * *

To be circulated for the consideration of the Chiefs of Staff

J.I.C. (51) 6 (Final)

19th January, 1951.

CHIEFS OF STAFF COMMITTEE

JOINT INTELLIGENCE COMMITTEE

THE SOVIET THREAT

Report by the Joint Intelligence Committee

JOINT INTELLIGENCE COMMITTEE

THE SOVIET THREAT

Report by the Joint Intelligence Committee

1. We state below the present military strength of the Soviet Union, the trend of current developments and conclude with our views on the need for rearmament.

MILITARY AND ECONOMIC STRENGTH OF THE SOVIET UNION Soviet Army

2. The general distribution of Soviet Army formations is as follows:–

|

Line Divs

.

|

Tank Divs

.

|

Arty. And A.A. Divs

.

|

Total

|

|

|

E. Europe and W. Russia

|

34

|

13

|

16

|

63

|

|

Balkans and Black Sea

|

29

|

3

|

3

|

35

|

|

Central Russia

|

19

|

1

|

1

|

21

|

|

Caspian

|

29

|

-

|

6

|

35

|

|

North Russia

|

15

|

-

|

1

|

16

|

|

Siberia

|

6

|

-

|

-

|

6

|

|

Far East

|

26

|

3

|

10

|

39

|

|

Total divisions

|

158

|

20

|

37

|

215

|

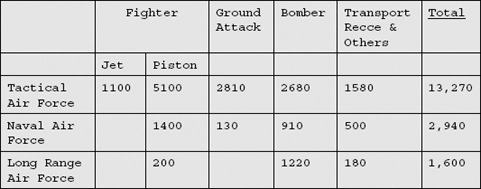

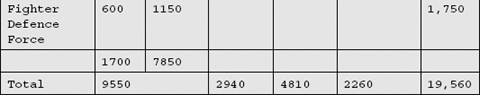

Soviet Air Force

3.

Soviet Navy

4.

|

Army

|

Baltic & Arctic

|

Black Sea

|

Far East

|

Total

|

|

Old Battleships

|

1

|

2

|

-

|

3

|

|

Monitors

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

1

|

|

Cruisers

|

7

|

7

|

3

|

17

|

|

Destroyers

|

72

|

20

|

46

|

138

|

|

Submarines (Ocean)

|

100

*

|

15

|

64

|

179*

|

|

Submarines (Coastal)

|

54

|

36

|

40

|

130

|

|

Midget Submarines and Coastal Craft

|

Large Numbers

|

Large Numbers

|

Large Numbers

|

Large Numbers

|

*

This includes 25 obsolescent craft under long refits and ex-German submarines.

Atomic Weapons

5. A combined Anglo-U.S. atomic energy intelligence conference has just concluded that the most likely size of the Soviet atom bomb stockpile will be 50 in mid-1951. Production is continuing, and may be stepped up considerably in about two years’ time.

Soviet Armament Production

6. Our estimate of current Soviet production of the principal armaments is as follows:–

|

Monthly rate of production (units).

|

|

|

(a) Aircraft

|

|

|

Jet fighters

|

400

|

|

Piston-engined fighters

|

20

|

|

Medium bombers

|

60

|

|

Long-range bombers

|

30

|

|

Transports

|

100

|

|

Trainers and others

|

240

|

|

Total Aircraft

|

850

|

Monthly rate of production (Units)

| (b) Tanks | 325 – 350 |

| (c) Self-propelled guns | 100 – 125 |

| Annual rate of production (Units) | |

| (d) Submarines (other than midgets) | 50 |

| (e) Fast coastal craft | 100 |

Soviet Industry

7. The general level of basic industrial activity in the Soviet Union has since the war surpassed that of the United Kingdom (e.g. her steel production now exceeds the United Kingdom’s by 70% and her electric power production by 55%) but is still greatly inferior to that of the U.S.A. That the Soviet Union has succeeded nevertheless in maintaining a rate of armament production greatly in excess of that of other countries, while proceeding simultaneously with the expansion of her industrial capacity, has been due to her readiness to sacrifice the standard of living of her people. For instance, only 9 per cent of her coal supplies and 13 per cent of her electric power supplies reach the domestic consumer compared with 25 per cent and 37 per cent in the United Kingdom. High as the current rates of Soviet armaments production are, and although they are increasing with the overall expansion of the economy, they could yet be raised to several times the present figures if the Soviet rulers decided to expand war production to the limits of the country’s capacity.

8. The amount spent on defence in the Soviet Union in 1949 was 13.4 per cent of the estimated national income as compared with 7.7 per cent in this country, even though the Soviet Union’s defence budget excludes a number of important defence items, among them research and development and strategic stockpiling.

PRESENT TRENDS

9. Ground Forces

. Since September last the Soviet forces in Germany have been over peace establishment by 40,000 men. The demobilisation of the 1927 class which would bring the forces back to normal is now overdue. Since October there has been a large increase in the strength of all of the East European Satellites, both in men and equipment. These facts coupled with recent signs of a redeployment of Soviet Occupation forces and an intensification of civil defence preparations, all indicate increased military preparedness.

10. Air Forces

. While not increasing appreciably in total numbers the air forces are steadily increasing in efficiency, both technically and in training. The recent decision to standardise on a single type of jet fighter and the development of a ring of modern airfields in the West also increases military preparedness.

TOP SECRET

11. Naval Forces

. The efficiency of the Soviet Navy is rising steadily and considerable effort is being devoted to the production of a high speed prototype ocean-going submarine, suitable for mass production on a scale of 150 submarines a year. Cruisers and destroyers are being built to the limit of capacity and 4 cruisers and 16 destroyers will be added to the fleet this year.

12. Economic

. While continuing to expand its basic industries, the Soviet Union is now paying increased attention to developing the engineering and other manufacturing industries, and in particular to the electronics industry, to increasing industrial efficiency and to training skilled labour. These measures will all contribute to strengthening her economic war potential. Stockpiling, though not yet on a large scale, is diminishing the Soviet bloc’s dependence on supplies of raw materials from non-Communist countries.

THE CASE FOR REARMAMENT

13. Except for the atomic bomb the Soviet Union has an immense superiority over the West in ground and air forces. It also has the largest submarine fleet in the world.

14. In the present state of the defences of the free world, there is a grave danger that, through aggression by proxy or subversion from within, the Soviet Union will gain control of the raw materials, especially tin and rubber, of South-East Asia: materials which not only earn dollars, but contribute to the independent defence effort of the United Kingdom. In the same way it might well secure the Middle East oil which is vital to the economy of the United Kingdom in peace and without which the West could not sustain a prolonged war. In a global war the Soviet Union could very probably carry out at one and the same time campaigns which would win it not only these prizes but also the industrial heart of Western Europe.

15. The only way in which the West can be sure of preventing these developments is to provide itself, before it loses the benefit of the deterrent of the atomic bomb, with armed forces adequate to deter or defeat local aggression and to deter the Soviet Union from deliberately starting a global war.

16. Unless such a force is at the disposal of the Western Powers the Soviet Union holds the strategic initiative, and the West will remain powerless to stop continued encroachment by the Soviet Union over the territories of the free world, or, in the event of war, the over-running of Continental Europe. The survival of the United Kingdom would then be in jeopardy. At best we should be faced with a long war of recovery and reconquest backed only by the resources of the Western Hemisphere. In such circumstances we should be forced to comply with the wishes of the United States.

17. It is therefore imperative to deprive the Soviet Union of the power to use this initiative. We cannot tell when or even whether the Soviet Government will use it. But we do know that only the existing preponderance of the Soviet Army vis-a-vis the Western Powers made it possible for the Soviet Government to carry out its programme of expansion in Europe since the end of the war without direct resort to force. Either Soviet Communism or Russian Imperialism may be the main spring. In either case it is most unlikely that the expansionist programme is complete. The pronouncements of all Soviet Communist leaders proclaim their implacable hostility to all non-Communist Governments. Even today it is clear that the existence of Soviet forces on their present scale without any comparable force to set against them contributes to defeatism in France and in parts of Western Germany, and paves the way for further expansion.

18. The main purpose of Western rearmament is therefore to take the political initiative from the Soviet Union and to show that no easy conquests await it or its Satellites, either in isolated acts of military aggression in the cold war, or in global war. There is no question of building a force designed for aggression. The Western defence effort must be sustained until it is made clear to the Soviet leaders that the strength of the West forbids any further advance and makes some sort of negotiation essential. In this we must negotiate from strength. We cannot estimate how soon this point will be reached. We must recognise that the Soviet leaders think and plan in terms of a very long struggle.

19. Meanwhile, however, we can expect the Soviet Government to make strenuous efforts to hamper Western rearmament. Their efforts are unlikely to be confined to abuse and denunciation of the West. As they see the West building up its strength they may well try to reinforce their own position by accelerating their expansionist programme. They are likely to look for further key economic and strategic points to seize. The success achieved in Korea will no doubt in any case tempt them to accelerate their programme; the massive intervention of China in Far Eastern affairs leaves the Soviet Government greater freedom to act earlier elsewhere.

20. Some further Soviet expansion may have to be accepted. Other moves must be opposed by the Western Powers if their position is not to be weakened beyond hope of repair. Unless we have the forces to oppose such moves whenever they occur, the Western world will continue to be beset by threats of military aggression in the cold war against a background of a grave threat of global war. These conditions must render abortive all Allied efforts in diplomacy and social and economic progress, and we may well have no alternative left (short of surrendering ourselves to Communism) but to make full atomic war on the Soviet Union itself. Atomic war is no longer likely to be one-sided. The prospect is so grim that we can no longer allow ourselves to rely on this means of defence alone. We must in fact provide ourselves with other arms as an insurance against being drawn irresistibly into another world war.

Recommendation

21. We recommend that the Chiefs of Staff approve this report and use it as an intelligence brief for discussions on increased defence expenditure.

(Signed)

D.P. REILLY.

E.W.L. LONGLEY-COOK.

A.C. SHORTT.

N.C. OGILVIE-FORBES.

K.W.D. STRONG.

B.K. BLOUNT.

Ministry of Defence, S.W.1.

19th January, 1951

.

*

J.I.C. (48) 100 (Final)

†

Note: The Appendix B, which is referred to in Part I, contains an expansion of some of the arguments and certain additional data dealing with the period between now and the end of 1949. This is not being tabled as a part of the agreed U.K./U.S. appreciation.

This Appendix B was agreed on a working level at the request of the U.S. Intelligence Team for use mainly for detailed studies by U.S. intelligence and planning staffs.

This Appendix B was agreed on a working level at the request of the U.S. Intelligence Team for use mainly for detailed studies by U.S. intelligence and planning staffs.

‡

J.I.C. (48) 26 (0)

*

J.I.C. (48) 26 (0)

J.I.C. (47) 42 (0)

*

J.I.C. (U.K) (48) 100 (0) Part I, Paras 25-30.

†

J.I.C. (U.K) (48) 100 (0) Part I, Para. 109

‡

J.I.C. (U.K.) (48) 100 (0) Part II, para. 70.