JIC (68) 54 (Final)

2nd December 1968

THE SOVIET GRIP ON EASTERN EUROPE

Report by the Joint Intelligence Committee (A)

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

1. The aim of the paper is to assess the importance to the Soviet Union of Eastern Europe, and the ways in which the Soviet government will seek to maintain its grip in the foreseeable future. The paper deals with the political, military and economic requirements of the Soviet Union in Eastern Europe and the implications of likely Soviet policies for the countries in the area, and for East-West relations. Likely trends are assessed against the background of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.

2. Since the end of the Second World War, successive Soviet governments have imposed political, military and economic requirements on the East European governments. Political requirements have included a monopoly of power for the Communist Party, and absolute obedience to the Soviet Union in all matters of substance. Military requirements have involved making the national territory of each country available to the Soviet Union when needed; accepting Soviet assessments in military affairs and Soviet domination of the country’s armed forces and defence policy; and where necessary the stationing of Soviet forces on its territory. The threat of military force has always been implicit behind Soviet demands, and has been a significant factor in gaining their acceptance. Economic requirements have meant collaborating with the Soviet Union and other East European

countries in the work of the Council for Mutual Economic Aid (CMEA), and running the economy of each country in accordance with Communist practice in the Soviet Union. At the same time, the national interests of the countries of Eastern Europe often conflicted with Soviet requirements, and Soviet policy towards the countries of the area was never consistent or carefully planned.

3. However, in Soviet eyes, the most important of these requirements were called into question by the Czechoslovak reform programme and the results of the liberalising trends which stemmed from the election of the Dubcek leadership in January 1968. The official reform programme, which advocated separation of Party and government functions and an apparent withdrawal of Party control over aspects of security policy and the armed forces, as well as the end of censorship was regarded in Moscow as prejudicial to the maintenance of the leading role of the Communist Party in the country. The replacement of tried and experienced political, military and security officials by the Dubcek regime may have worried a Soviet leadership which traditionally laid great stress on the selection of key personnel in East European countries. The end of censorship and the licence to criticise Party thinking and to explore liberal ideas was regarded as dangerously “infectious” throughout the area and even in the Soviet Union itself. The Soviet military leaders probably feared that a serious gap in the Warsaw Pact defence structure might develop either by the defection of Czechoslovakia from the Pact, or through a decline in the efficiency of her armed forces. In economic affairs the Russians feared that the more radical economic ideas on the need for greater economic freedom and closer contacts with the West could have led to a weakening of the Party’s power in economic matters and a growth of Western, especially West German, influence, with a corresponding loosening of Czechoslovak ties with their communist allies.

4. The Soviet military occupation of Czechoslovakia effectively destroyed the possibility, never very strong, that the present Soviet leader would tolerate the loss of orthodox communist party control in an active member of the Warsaw Pact. The effect of the invasion in Eastern Europe will, in the short term, be to strengthen the influence of the countries and personalities most loyal

to the Soviet Union, and to induce fear of Soviet military might and Soviet readiness to use it against actual or potential dissidents in the area of the Warsaw Pact. In the longer term, the invasion may strengthen currents of unrest in Eastern Europe which could cause concern to the East European governments. Thus, one important effect may be to focus Soviet attention inwards on to the problems of Eastern and Soviet relations with the countries of the area; for the Russians will be anxious to ensure that any future moves for change, e.g. economic reforms, do not develop in the kind of political atmosphere which appeared in Czechoslovakia in the first part of 1968.

5. In the short term, at least, the outlook for Czechoslovakia is bleak. A Soviet military presence in the shape of a group of Soviet forces will continue for some time, and Soviet forces will always be available in neighbouring countries to intervene again if necessary. The Dubcek regime will try to cushion the Czechoslovak people against the worst effects of the Soviet intervention, but what appears to be the gradual erosion of the regime’s freedom of manoeuvre by Soviet policy may ultimately lessen and perhaps destroy the popularity which the leadership has so far enjoyed with the Czechoslovak people. However, some elements of the Dubcek reform programme, notably the economic proposals and the establishment of a federal structure for the State, will continue, and the fact that the Soviet Union agreed to the return to power of the legitimate government of the country under the Moscow protocol of 27th August suggests that the Russians still want to work within the terms of this arrangement.

6. The present leaders of East Germany, Poland and Bulgaria will be relieved that the danger of “infection” to their countries has been eliminated, at least temporarily, and their loyalty to the Soviet Union will have been strengthened. In Hungary, where much sympathy for the Czechoslovak reforms existed, the intervention was undoubtedly a personal blow to Kadar, who will probably have to proceed more cautiously. The Rumanians, while maintaining their criticism of the Soviet action, will aim at preserving the essence of their independent stand: their economic freedom of action and their independent foreign policy, on both of which the Rumanian leaders’ nationalist policy largely depends, at the expense, if necessary, of political gestures on international issues where Rumanian interests are not directly concerned. But Soviet economic and political pressures will continue with the long-term intention of subverting the present Rumanian leadership. Yugoslavia will continue her opposition to Soviet policy in Czechoslovakia; she is alarmed by recent Soviet talk of the overriding interests of the “Socialist Commonwealth” and the potential effect on national sovereignty. A prolonged period of cool relations with the Soviet Union is likely.

7. Militarily, the Czechoslovak occupation has eliminated the Soviet fear that the Czechoslovaks might defect from the Warsaw Pact. Thus the situation in which Czechoslovakia is regarded, in Soviet eyes, as a buffer zone between the West and the Soviet frontier, has been restored. However, the effective loss of the Czechoslovak armed forces in the potential offensive role means that Soviet operational plans will have to be re-assessed and their own military commitments extended. In addition, events leading up to the Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia will make future proposed Warsaw Pact exercises extremely delicate political issues and may complicate, at least in the short term, plans for improving the structure of the alliance. The Soviet Union may aim to achieve even tighter control over the East European armies.

8. In the economic field, the occupation has restricted potential Czechoslovak moves towards closer economic and technical co-operation with West Germany and the West in general, but it has not altered the basic economic problems of Czechoslovakia or Eastern Europe, which remains dependent on the Soviet Union, particularly for supplies of raw materials (crude oil and iron) and also in some cases grain and electrical energy. The possibilities for strengthening CMEA may even have been improved in the post-invasion circumstances, for the Soviet Union will be anxious to correct CMEA’s shortcomings, if only as a counterbalance to the political and military effects of the invasion, and a number of East European proposals are in existence which might be taken up at future meetings of the Council. There is also the continuing attraction for the East European countries of economic links with the West, and this is a trend of which the Soviet Union will have to take account. Much depends therefore on the Soviet Union, but its leaders may decide in the longer term to take more account of national economic ambitions and existing economic differences between the members of CMEA.

9. The implications for East-West relations involve a set-back to hopes of the growth of a more liberal Eastern Europe which could play an important part in bringing about a comprehensive European settlement. While the evidence suggests that the Soviet action in Czechoslovakia was essentially to preserve an orthodox Communist regime, it has introduced new uncertainties about Soviet actions and the situations in which the Russians may be prepared to use armed force. It seems unlikely that because the Soviet Union used force in Czechoslovakia she will be more willing to do so henceforth in order to extend her influence in the Mediterranean or the Middle East. However developments in Eastern Europe might make her feel obliged to use force there again even at the risk of provoking a reaction from NATO countries. We believe that the strategic balance between the super-powers will not be affected, and Soviet-American contacts on political and defence matters will continue. Indeed, the Soviet Union has an interest in restoring a “business as usual” relation with the West, and is anxious that its actions in the Warsaw Pact area should not affect East-West relations elsewhere.

10. We therefore conclude:

(a) The Soviet Union has shown that it will use its armed forces within Eastern Europe to preserve a Communist regime which they consider vital to basic Soviet political, military and economic interests. Both the West and Eastern Europe must assume that Soviet readiness to use force for these purposes in the Warsaw Pact area will remain valid for the foreseeable future.

(b) The Soviet action in Czechoslovakia was, however, a defensive one inside the area covered by the Warsaw Pact. It has probably succeeded in removing both a political and a potentially serious military weakness in the central sector of the Pact’s area of responsibility. We do not believe that because the Soviet Union used force in Czechoslovakia she will be more willing to use it in areas of East-West confrontation, such as the Mediterranean or the Middle East. But the Russians

could use force again in Eastern Europe even if this provoked a reaction from NATO countries, and many areas of uncertainty in the Soviet attitude towards the use of force have emerged from this crisis. However, there is no reason to believe that the strategic balance between the East and the West has changed.

(c) In the short term, the Soviet grip on Eastern Europe has been tightened by the demonstration that Soviet leaders are prepared to use military force where their interests are threatened with erosion. This demonstration will be a discouragement to liberal movements inside and outside the ruling East European Communist Parties. It has buttressed the Old Guard regimes at the expense of widening the gap between the Party leaderships and the public, especially in Poland. In Hungary, Kadar’s policy of reform and national reconciliation has been seriously threatened, and Rumania’s freedom of manoeuvre has been limited by her need to emphasise her solidarity with the Warsaw Pact.

(d) In Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union will seek to use its position of strength to reimpose acceptance of the full range of Soviet requirements by the Dubcek regime. The latter will try to fulfil the minimum Soviet demands while protecting the population from the full rigours of direct Soviet rule – although it may lose some of its popularity with the people in the process. But it must be recognised that the Soviet Union has the power to remove Dubcek at any time, and to replace him and his colleagues by more pliable leaders.

(e) The Soviet grip on Eastern Europe is so important to the Russians that it is unrealistic to expect major changes in Eastern Europe except in the context of some significant change in Soviet attitudes. There may be some spontaneous evolution in the Soviet Union and, in the longer run, pressures from Eastern Europe will begin to have an effect on the Soviet Union. Nationalism will be an increasingly powerful force. Among the young people of Eastern Europe a process of growing resentment against the existing order may appear which may ultimately be expressed by methods of protest already used by the younger generation in the West. Economic pressures, which in Czechoslovakia opened the way to the political and social reform movement, will continue to be exerted on Communist leaderships in the direction

of greater efficiency, more freedom of action and individual responsibility including increased trade and contacts with the West. There will, therefore, be continuing pressure in Eastern Europe towards both economic and political liberalisation with which the Soviet Union will be confronted, and these pressures may in the long run find outlets which the Soviet Union will no longer use force to block.

(Signed) EDWARD PECK

Chairman, on behalf of the

Joint Intelligence Committee

(A)

Joint Intelligence Committee

(A)

Cabinet Office, S.W.1.

2nd December 1968

Annex to JIC(68) 54 (Final)

THE SOVIET GRIP ON EASTERN EUROPE

INTRODUCTION

1. The aim of the paper is to assess the importance to the Soviet Union of Eastern Europe, and the ways in which the Soviet Government will seek to maintain its grip in the relatively short term. The paper deals with the political, military and economic requirements of the Soviet Union in Eastern Europe, factors influencing their fulfilment and the implications of likely Soviet policies for the countries in the area and for East-West relations. Likely trends are assessed against the background of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.

GENERAL FACTORS

The Background to Soviet Policy in Eastern Europe

2. Since the end of the Second World War, when the Soviet Union came into military possession of Eastern Europe, successive Soviet governments have established a number of requirements in Eastern Europe corresponding to the political, military and economic policies of the Soviet Union of the time. Each Soviet Government chose its requirements within the framework of the Soviet Union’s right to “super-power” status, and of the ever present Soviet claim that Eastern Europe should be acknowledged as the Soviet Union’s main “sphere of interest” – rather as the “Monroe Doctrine” has been applied by the United States in relation to the New World.

3. After eight years of Stalin’s rule of Eastern Europe as an extension of the Soviet Union, with its emphasis on police methods and economic exploitation, Khrushchev spent much time and energy attempting to “rationalise” Soviet political domination of the area. By relaxing Stalinist rule, reorganising the military forces of the East European countries within a multi-national alliance, and by encouraging each state to remove the worst features of Stalin’s economic system, Khrushchev appeared to be searching for a workable relationship between the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe which would guarantee absolute political loyalty to the Soviet Union without the need to hold down the area by brute force. Like Stalin’s before it, however, the Khrushchev leadership had its failures, and in 1956 resorted to military invasion to keep Communism in power in Hungary.

Soviet Requirements in Eastern Europe under Brezhnev and Kosygin

4. Brezhnev and Kosygin and the collective leadership which they head have presided over some important changes in Soviet policy, including the development of capabilities aimed at effecting a Soviet presence overseas, but in East European affairs their approach appeared to differ little at first from that formulated by Khrushchev. Brezhnev and Kosygin began by accepting the East European leaderships inherited from Khrushchev, even though one of them, the Rumanian, was showing signs of deviation along nationalist lines in foreign and economic policy. As time went on, the Soviet leadership somewhat hardened its ideological line in Eastern Europe. Dismay at the decline of Communism as a doctrinal inspiration both inside the East European Parties and in the Parties of Western Europe became a feature of the Soviet outlook. Moreover, the increasing outspokenness of East European and Soviet intellectuals and the ideological apathy prevalent in West European Communist Parties led the Soviet leaders to seek ways of injecting new life into the movement as a whole – a trend reflected in the Karlovy Vary conference of Communist Parties in 1967 and the theses prepared for the 50th anniversary of the Russian Revolution in November 1967.

5. Whatever the motives for this new emphasis on ideology, its relevance to Soviet requirements in Eastern Europe is undeniable, for it buttressed the Soviet Union’s political needs. These requirements represent the Soviet view of their vital interests in Eastern Europe, and may be summarised as the retention in power in each East European country of a loyal Communist Party which should:

(a) exercise absolute control of all political power in the country, and, in conjunction with Soviet experts, dominate all security and intelligence activity;

(b) entrust all key Party and government posts to Party members enjoying the confidence of the Soviet Union;

(c) control education, the press, radio and television;

(d) maintain well-trained national armed forces of unquestioning loyalty to the Soviet Union, and accede to all Soviet requests for the use of national territory and resources for Soviet or Warsaw Pact military purposes, accepting, at all levels, Soviet military appreciations of Western intentions and Warsaw Pact capabilities;

(e) maintain an efficiently-run economy and external trade policy capable of supporting a rising standard of living, subject always to using methods in conformity with Soviet practice and interests; co-operate with the Soviet-sponsored Council for Mutual Economic Aid (CMEA);

(f) support the general line of Soviet foreign policy, particularly with reference to the German question, nuclear policy, and assistance to established Communist states involved in hostilities, e.g. North Vietnam;

(g) support the Soviet Union’s position in intra-Bloc disputes;

(h) keep current trends towards intellectual freedom within bounds, retaining censorship to prevent the dissemination of non-Communist and “anti-Soviet” views.

6. The Soviet view of its military requirements in Eastern Europe is primarily concerned with the security of the Soviet Union’s open Western frontier, but is also concerned with the deployment of Soviet forces in Europe in the most advantageous position to fight a European campaign should hostilities break out. The Soviet Union requires in essence that the East European governments should do everything in their power to support the Soviet forces, and actively assist them in achieving their peacetime and wartime aims which may, in greater detail, be listed as follows:

(a) in peacetime:

(i) to maintain the political status quo in Eastern Europe, providing a buffer zone between NATO and the Soviet Union.

(ii) to continue the division of Germany on a permanent basis in order to safeguard the Soviet Union against the consequences of a re-emergence of German military power.

(iii) to command and control the Warsaw Pact forces, and direct the co-ordination of their training and equipment.

(iv) to control the air defence of the area.

(b) in wartime:

(i) to defend the territory of the Soviet Union by ensuring that ground and air operations are conducted as far to the West as possible.

(ii) to destroy NATO forces and occupy NATO territory.

(iii) to protect Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union from air attack.

Complicating Factors in Soviet Policy towards Eastern Europe

7. Before the introduction of the Czechoslovak reform programme, most of the East European governments were by and large fulfilling these requirements. But the process was greatly complicated by pressures arising from the special interests and requirements of the East European countries, and their bilateral relations with the Soviet Union and with each other. The Russians did not consistently treat them all in the same way. Soviet objectives in Eastern Europe were also variable, as were the tactics they pursued: for example, there were periods when deviation from standard Soviet practice in individual East European countries led to harsh Soviet reactions, while on other occasions the Soviet leaders seemed to be prepared to acquiesce in nationalist or even liberal manifestations in certain countries, mainly in economic affairs.

8. The German problem is at the heart of Soviet policy towards Eastern Europe. It is a cardinal point of Soviet policy that the German population in Central Europe should remain divided, and the Russians therefore promote the claim of the East German regime to be a second German State. The continued existence of West Berlin as an outpost of the West under allied occupation is a source of strain between the Russians and the East Germans, who sometimes appear to be trying to manoeuvre the Russians into policies designed to make the Western position in the city untenable. The Russians are generally prepared to permit the East Germans to engage in minor harassment, and on occasion have themselves taken part in such activities. But although the Russians have in the past undertaken more serious measures against West Berlin and the access routes, there have been no recent signs that they want a major crisis over Berlin or a confrontation with the allies over allied rights in the city.

9. The Poles and the Czechoslovaks have deep and persistent fears of German militarism which created a genuine interest in the protective shield of the Warsaw Pact. But fear of German power has not been felt to the same extent in Hungary, Rumania and Bulgaria, and even in countries where such memories were bitter, the anti-German bogey has been used so intensively and indiscriminately in Soviet propaganda that some of its credibility may have been wearing thin – especially with the younger generation. This diminishing credibility may have added to the doubts which always existed about the degree to which the Soviet Union really feared a West Germany which had no access to nuclear weapons, was a full member of the NATO alliance, and had accepted the same limitations on its military policy as all the other members of the alliance.

10. Contradictions and uncertainties in Soviet policy in Eastern Europe also arose as a result of Rumania’s successful defiance of Soviet rulings on relations with West Germany and Israel, on military liabilities under the Warsaw Pact, as well as on obligations towards CMEA. While Soviet relations with Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria were more stable, there were in each case specific issues on which the Soviet leaders were obliged to pay attention to national peculiarities and interests which worked against a uniform application

of Soviet requirements in Eastern Europe. Some of these individual peculiarities were associated with potential struggles for power and succession problems in the leaderships of the Communist Parties, and others with the varying degrees and types of pressures brought to bear on these leaderships by their populations. In all these factors the force of nationalism in East European countries has played an important role.

11. Economic problems also brought their contradictions to the ruling Parties’ attempts to fulfil Soviet requirements. Soviet insistence on the primacy of Soviet economic interests and models clashed to some extent with the kinds of economic reform which most of the East European countries realised were necessary, both for internal economic progress and for external trade. The lack of any authority in CMEA to enforce its decisions on member countries has enabled the Soviet Union – as the dominant partner – to derive maximum benefit from the organisation, particularly in the sphere of foreign trade. Apart from Rumania, whose dispute with CMEA was on important issues of principle, none of the other East European countries has sought – or indeed was in a position – to abandon CMEA or disrupt its arrangements. Their efforts were directed rather towards improving the existing machinery. Amongst the proposals put forward were more rational specialisation of production, improvement of foreign trade pricing and the system of payments settlement through some form of rouble convertibility, and a general tightening up of discipline with regard to intra-CMEA commitments and obligations.

12. Military requirements were of vital importance to the Soviet Union, but evidence of the period before the Czechoslovak crisis suggests that contradictions similar to those in the political and economic fields were less obvious. With the exception again of Rumania, which had no frontier with a NATO country, all the active members of the Warsaw Pact appeared to be fulfilling Soviet military requirements, and Soviet satisfaction with the military scene may be deduced from the fact that the last significant change in the number of Soviet forces in the area took place in 1958.

The Soviet View of the Czechoslovakia Reform Programme

13. The Czechoslovak liberalisation programme and the political, military and economic developments in the country which stemmed from it can be summarised under three main headings:

(a) official acts of political, economic and social reform;

(b) personnel changes at the highest level in the Party, the government and the armed forces;

(c) semi-official and unofficial activity by liberal elements anxious to quicken the pace of reform in the country.

14. There seems little doubt that the Soviet leaders believed that elements of this programme threatened the monopoly of decision-making of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, and exposed a lack of will-power on the part of the Dubcek leadership to maintain orthodox Party rule in the country. The Russians’ decision to go ahead with the military occupation of the country may have been directly connected with Soviet interpretations of Dubcek’s intention to reorganise the whole structure of the Czechoslovak Communist Party at the September Party Congress, and the probability that this Congress would elect a liberalising Central Committee of the Party which would be its constitutional authority for at least two or three years. The Russians appeared to believe in any case, that the atmosphere in which the Dubcek reforms were being debated and put into effect (including the relaxation of censorship) was contributing to loss of control over the country by the Party, and made reforms which could be tolerated under Kadar’s more orthodox and cautious leadership in Hungary, for example, difficult to support in Dubcek’s Czechoslovakia. Some of Dubcek’s actions may have suggested to the Russians that if they were carried to what the Soviet leaders saw as their logical conclusion, Czechoslovakia would cease to be a member of the Soviet bloc, cease to adhere to the basic tenets of Marxism-Leninism as interpreted in the Soviet Union, and would be either unable or unwilling to meet the full range of Soviet military requirements. In this connection, it is important to recognise that Soviet actions were as frequently based on their leaders’ interpretation of the possible consequences of Dubcek’s methods and intentions as with actual measures which his regime had put into effect.

The Future of Soviet Policy towards Eastern Europe

15. There is no doubt that the Soviet Union regards Eastern Europe as of vital importance to her and that she will seek to maintain her grip there. As they look ahead and consider the growth of Chinese power, the Russians will see no reason to alter this assessment. The Soviet Union’s future policy towards Eastern Europe in the light of the occupation of Czechoslovakia, both in the short and the longer term may conveniently be grouped under three headings: political, military and economic.

THE POLITICAL OUTLOOK

The Soviet Union

16. The most immediate effect of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia was the removal of all doubts that the Soviet Union was and will be prepared to use its military forces to uphold its political and military requirements within the area covered by the Warsaw Pact. Despite a brave and ingenious display of non-military resistance by the Czechs and Slovaks, the Soviet military moves were swift and efficient, and put the Soviet government in a position from which it could exercise a decisive influence on events in Czechoslovakia.

17. One of the important factors in assessing the future course of events in Eastern Europe is the effect which the resort to force in Czechoslovakia will have on the Soviet leadership itself. It is impossible to tell whether or not the Soviet Politburo was divided on the issue, or if it was, which members of the leadership supported military action and which opposed it. While military factors described below in para. 45 ff. must have weighed heavily with the leadership, there is no evidence that the Politburo came under strong pressure from the Soviet military to intervene. We are inclined to the view that as the crisis developed and in Soviet eyes came increasingly to endanger the continuation of orthodox Communist rule in Czechoslovakia and of Soviet security arrangements in Eastern Europe, the Politburo probably closed ranks, and achieved unanimity at the moment of decision-making. Any divisions of opinion and hesitations within the Politburo were probably not over the desirability of putting an end to the development of liberal communism in Czechoslovakia, but over ways and means of doing so.

18. At the culmination of this crisis, at all events, the Soviet collective leadership showed a capacity to act decisively, as it has done on other occasions, for example, the decision to extend military aid to North Vietnam in 1965. The fact that the Soviet leaders resorted to force in Czechoslovakia may encourage them more readily to use force or the threat of force again within the Warsaw Pact area in order to bring recalcitrant leaders to heel.

19. This general hardening of the line in Moscow appears to have been reflected in attitudes towards Communist doctrine and the rights and obligations of ruling Communist Parties. The article on this subject in “Pravda” of 26th September 1968 laid down that a Communist country has the right to self-determination only so far as this does not jeopardise the interests of other Communist states (“the Socialist Commonwealth”), that each Party is responsible to the other fraternal Parties as well as to its own people, and that the sovereignty of each country was not “abstract” but an expression of the class struggle, e.g. that the Soviet Union had the right to define each country’s sovereignty.

20. While the Soviet leaders have tightened their direct control over events in Czechoslovakia, restated their political requirements for Warsaw Pact countries and demonstrated their readiness to use military means to enforce then, the Russians must also be aware of the miscalculations which they made in the political preparation of the occupation. It is very likely that they expected to find sufficient numbers of collaborators with whose help a pro-Soviet government could be formed as soon as the occupation became effective, and they were certainly taken aback by the unity and resourcefulness of the Czechoslovak people, and by the absence of political figures willing to serve in a Soviet-sponsored government. The Soviet Union’s resumption of dealings with Dubcek and the legal Party and State leadership at the end of August 1968 suggests that the Russians abandoned their attempt to instal a regime of collaborators, and decided to compromise rather than make Czechoslovakia a military province, and to present their demands for the rectification of the political situation in Czechoslovakia to the regime which they had originally hoped to overthrow.

21. The reaction of the Soviet leadership to their occupation of Czechoslovakia may therefore be three-fold:–

(a) that their capability to use military means within the Warsaw Pact area in pursuit of political objectives has been supported by the will to act, and this demonstration, they may believe, will promote a greater sense of conformity with Soviet demands in Eastern Europe;

(b) that Soviet understanding of, and intelligence on, the East European countries, Party leaderships and national aspirations was faulty, and could lead in the future to further miscalculations;

(c) that nationalism is strong even within the friendliest Communist countries in Eastern Europe, and that it may not be worth insisting on complete compliance with Soviet wishes provided that the main Russian requirements are met.

The Russians may conclude that while their capability and determination to take firm action has been successfully demonstrated, their ability to take appropriate preventive action at the political level before the last resort is reached should be improved. The Soviet leaders may therefore decide to complete the restoration of orthodox Communist rule in Czechoslovakia, using, as long as possible, the legal Dubcek Party leadership to implement Soviet requirements. The Russians may complement their policies towards Czechoslovakia by a longer term overhaul of their relations with each East European country in the light particularly of the political miscalculations which emerged from their handling of the Czechoslovak crisis. But in the short term, we should be in no doubt that the Soviet loaders will insist that their requirements are met in Czechoslovakia.

22. It is beyond the scope of this paper to consider internal developments in the Soviet Union, but it is necessary to stress that the Soviet grip on Eastern Europe is so tight and so important to the Russians that it is unrealistic to expect any major change in Eastern Europe without the agreement or acquiescence of the Soviet Union. Since the status quo suits the Soviet Union well, the Russians are unlikely to agree to major changes unless there are moves for change inside Russia. Whatever evolution does take place spontaneously in the Soviet Union, other strong pressures are likely to come from the countries of Eastern Europe themselves. For Eastern Europe is very vulnerable to change: it is closer to the West and its countries lack the long-standing Soviet

traditions of Communist bureaucracy. The East European pressures for change which include nationalism, the drive for greater economic and administrative efficiency, and more freedom of action and individual responsibility are bound to have important long term effects in the Soviet Union. Among young people in Eastern Europe, a process of resentment against the existing order may appear which may ultimately be expressed by methods of protest already used by the younger generation in the West, and even this may spread to the Soviet Union. The Soviet leaders, we believe, will continue to fight change, but in the long run they may not be able or willing to do more than to slow down and delay the process.

Czechoslovakia

23. There is little hope that the Czechoslovak leadership under Dubcek can do more than fulfil the requirements of the Soviet Union, while trying, in increasingly adverse conditions, to retain the loyalty of the Czechoslovak people. Certainly the regime will hope to salvage something from the Action Programme and to soften the impact of the reintroduction of censorship, of Soviet personnel into key Ministries (if this should happen on any large scale) and of a prolonged military presence in the country under the terms of the treaty signed on 16th October 1968. Although the Russians have agreed to remove the bulk of their forces, leaving a “Group of Forces” behind on an indefinite stay, Dubcek and his colleagues must be aware that they cannot regain such independence as they enjoyed before the invasion. Indeed, the room for manoeuvre of the Czechoslovak regime (whether under Dubcek or a more amenable successor, or even Soviet military rule) has been diminishing steadily, and depends effectively on decisions taken in Moscow.

24. While the Russians hold nearly all the significant cards in Czechoslovakia, their policy since the Moscow agreement of 27th August 1968 has contained elements of hesitation and delay. Having achieved some of their immediate political aims, e.g. the abandonment of the 14th Party Congress originally scheduled for 9th September 1968, and the annulment of the Extraordinary Congress held in the week of the invasion, the Russians may have been content to take their time in achieving “normalisation”. Provided he was willing to meet Soviet policy requirements, such an approach might help Dubcek

in his relations with the Czechoslovak people, and, in the longer term, it might provide a better atmosphere for the emergence of a pro-Soviet political group with whom, presumably, the Soviet leaders would prefer to work.

25. The future of the Czechoslovak armed forces is another problem which faces the Russians. Their loyalty to the Dubcek regime throughout the crisis renders them, in the Soviet eyes, of doubtful value as an ally of the Soviet Union. Disbandment of the Czechoslovak forces now seems to be out of the question. However, the Russians may consider it necessary to replace the more liberal minded officers and to make some organisational adjustments although not on the scale applied to the Hungarian forces after the 1956 uprising. The most likely solution is some reduction in size, consequent on the removal of the liberal elements, followed by a gradual resumption of their former role within the Warsaw Pact, under close Soviet supervision.

26. Among elements in the Czechoslovak reform programme which may survive will be some of the economic proposals. While any proposals believed by the Russians to be disruptive of CMEA will be banned, it seems possible that measures of internal flexibility such as those introduced at the beginning of 1967 and normal East-West trade will be approved. The Russians will be anxious not to impede a rise in the standard of living in Czechoslovakia or to veto methods of improving efficiency in industry and trade, so long as these do not threaten to disrupt established Soviet practices and commitments.

27. Nevertheless it is hard to see Czechoslovakia attaining any substantial measure of independence of Soviet policy. Liberalising currents are likely to continue, however and pressures will continue within the country for internal reforms.

East Germany

28. In many important respects the East German Party and Government has gained from the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia. This is partly due to the fact that Ulbricht’s position has been strengthened by the tough Russian action, for no Soviet government would now be interested in replacing a man of Ulbricht’s dedication to the Soviet cause, even though he may not last very long in power because of his age. East Germany has also gained because the invasion has halted, for some time at least, possible expansion of Czechoslovakia’s economic and political contacts with West Germany; although the West German trade mission is still in Prague, the East Germans probably believe that Czechoslovak-West German ties will dwindle, and that all chances that the Dubcek regime would respond favourably to Bonn’s Ostpolitik have disappeared. Such a response was probably viewed in East Germany as the most pressing danger in the Czechoslovak crisis. The East German regime is also doubtless relieved that the process of liberalisation in Czechoslovakia has been stopped; the East German leaders showed signs of nervousness during the summer that their own population might become infected.

29. The relationship between Czechoslovakia and East Germany is a particularly delicate one: it is fragile for emotional and historical reasons, yet important to both in the economic field. To some extent the success of one works to the detriment of the other. East Germany may appear in Moscow to be a model of loyalty combined with efficiency. Its economy is strong, its relatively small numbers of known intellectual dissidents seem to be under control, and its armed forces appear to be disciplined and of high morale – all of which are important Soviet requirements.

30. On the other hand, East Germany still represents something of a liability to the Soviet Union. The country is still an artificial creation, born of the Soviet Union’s refusal to permit the subordination of all Germans to one government, and the East Germans’ preoccupation with German affairs cannot easily be reconciled with this long-term Soviet aim. Moreover, the East German press reaction to the Czech liberalisation programme was harsher than the Soviet, and there is evidence that Ulbricht consistently urged a tough line on Moscow. Yet when the invasion took place, East German popular reaction was hostile to the Soviet action: local and industrial Party organisations failed to produce the necessary resolutions of approval, demonstrations in support of Dubcek took place, and citizens called at the Czechoslovak Embassy in East Berlin with petitions opposing the occupation. The authorities have since taken strong measures to deal with opponents of the invasion. East Germany’s development of its own nationhood and a more articulate public opinion, combined with

its economic stability, efficiency and rising standard of living, may in the longer run generate more tensions with the Soviet Union than its present ideological correctness and political loyalty to the Russians may suggest.

Poland

31. Reports from Poland before the occupation of Czechoslovakia suggested that the Polish leadership generally upheld Soviet criticism of the Czechoslovak reforms, and since 21st August have given full public support to the invasion and the official reasons for it. The latter have included military reasons, the alleged threat from West Germany and the danger of Western subversion inside Czechoslovakia, though no doubt the fear of infection in Poland had the Dubcek reforms been accepted by Moscow played an important part in securing Polish support for the occupation.

32. The reaction of Polish intellectuals, however, to the invasion was one of great hostility, of which the open letter by the Polish novelist Andrzejewski, expressing solidarity with the Czechoslovak writers, was one remarkable example. The majority of students, too, probably opposed the invasion, and the danger of unrest by the younger generation is probably assessed by the Polish authorities as still high. It may increase when Gomulka finally steps down especially if, in the course of a struggle for the succession, one or more contenders rely on the support of younger people or anti-Russian elements. Poland has a tradition of freedom and nationalism with which the Russians have always had to reckon, and their preoccupation with this factor may increase in the longer term.

33. At the top, however, the Soviet grip on Poland is not likely to be shaken in the short or medium term, and the present Polish regime will hardly query or evade Soviet political or military requirements. On the economic side, too, Poland is unlikely to cause the Russians undue concern. For its part, the Soviet Government will no doubt underline, in its dealings with Poland, the security which the Warsaw Pact offers to Poland, and the Russians’ proved ability and intention to act firmly and quickly in defence of their requirements. In the longer term, when Gomulka is no longer in power, the future of the Soviet-Polish relationship may depend in part on

whether the Polish leadership falls under the modernising influence of Gierek, or the nationalist influence of General Moczar.

Hungary

34. During the development of the Soviet-Czechoslovak crisis the Hungarian party leader, Kadar, seemed to play a dual role, approving the Czechoslovak reform programme, which was relevant to the reform policies which he was implementing in Hungary in a more subdued and cautious atmosphere, and at the same time remaining loyal to the Soviet Union. Kadar was clearly anxious to avoid armed intervention, but in the last resort, when his mediation failed to produce a compromise acceptable to the Soviet leaders, he was obliged to side with the Russians and send Hungarian units into Czechoslovakia.

35. The invasion was a personal blow to Kadar’s position both domestically and in his relations with the Soviet leaders. The Hungarian Press has maintained that Hungarian policies will be unaffected, but the Hungarians may now proceed rather more cautiously with their reforms, and the growth of economic ties with the West may be slowed down. It may even be that Kadar’s own position as leader of the Hungarian Party could be in doubt. In general, however, the effect of the Soviet action is likely to be similar in Hungary to that in Poland: in both countries, which are by tradition anti-Russian, the current mood in Moscow will be carefully assessed, and existing censorship and security regulations will be even more rigorously enforced.

Bulgaria

36. Little requires to be said about Bulgaria whose unswerving loyalty to all Soviet Governments since Stalin’s day has been one of the permanent features in Eastern Europe. The nominal Bulgarian Army contingent which participated in the occupation of Czechoslovakia was no doubt willingly provided on Soviet request, and there is every reason to believe that the Bulgarian Government viewed the Czechoslovak political reforms with hostility, although they themselves have approved a programme involving some reform of the economy of the country.

37. The loyalty of the Bulgarian leadership to Soviet policies and the primacy which the Soviet Union enjoys in Bulgarian decision-making are unlikely to be altered

by the Czechoslovak crisis. If anything, the Bulgarian Party leadership will be encouraged to take stronger action against their own dissident intellectuals (about one third of whom were reported to have been critical of the invasion) and students by the display of Soviet military power, and the long-term Soviet-Bulgarian relationship is likely to remain undisturbed.

Rumania

38. Rumania’s recent opposition to Soviet policy, with its strong undercurrent of nationalism, began in 1962–63 in the economic field, and was later extended to intra-Bloc affairs (the Sino-Soviet dispute), foreign policy (relations with West Germany and Israel) and the country’s military obligations to the Warsaw Pact. The Rumanian Government, which maintained a tight grip on the country’s internal affairs and operated a strict censorship, was not favourably disposed towards the Czechoslovak liberalisation movement, but was excluded from the series of conferences called by the Soviet Union to deal with the problem – in Moscow, Dresden, Warsaw and Bratislava – because of the Rumanians’ known opposition to interference in the affairs of other countries. The Rumanians criticised Soviet pressures on Czechoslovakia and condemned the military invasion. They ordered partial mobilisation and made clear their determination to resist an invasion of their own country. In spite of rumours of troop movements on their frontiers and fears of Soviet military intervention, the Rumanian leaders have upheld, though with diminishing intensity, their criticism of Soviet policy.

39. The Rumanian Communist Party, however, is not likely to relax its control over the country or weaken its monopoly of decision-making; and while this can be used to reduce Soviet influence in Rumania, it is difficult for the Russians to level accusations against the Rumanian leadership on this score. Nor is the Rumanian domestic model likely to prove attractive to other East European countries. But the Soviet Union will be sensitive to any sign that Rumanian foreign policy is attracting these countries, and will do her best to counteract any trends in this direction. Rumania’s natural resources and her strategic position (with no common border with a NATO country), set her apart from her allies and make it unlikely that, even if they wished to, the other

East European states could follow Rumanian policies in practice.

40. Rumania’s divergence, therefore, from Soviet requirements is neither dangerous to the Soviet Union nor, in the post-invasion atmosphere, particularly infectious. The Soviet Union will try to obtain the maximum benefit from its display of military power to intimidate the Rumanians and isolate them from their neighbours, with the long-term intention of subverting the present Rumanian leadership. The latter will concentrate on maintaining the ground already won in foreign and economic policy, while playing down points of disagreement with the Soviet Union on issues where Rumanian interests are not directly concerned. They may judge it wise to cooperate with their allies in holding Warsaw Pact exercises, and perhaps reforming CMEA, where this can be done without undermining the principles on which Rumania’s independent stand is based.

Yugoslavia

41. Yugoslavia’s reaction to the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia was one of violent hostility caused partly by the resurrection in Yugoslav eyes of Soviet demands for hegemony over Communist countries which precipitated the 1948 Soviet-Yugoslav split, partly by the feeling in Belgrade that Czechoslovakia was consciously following the Yugoslav model, and partly because the Soviet action confronted the Yugoslavs with a series of political, military and economic problems which they had successfully evaded for years.

42. There is no evidence that Soviet policy towards Eastern Europe involves military action against Yugoslavia in present circumstances. But it is now more difficult to say with any certainty what developments in Yugoslavia or in her relations with the West might be regarded by the Russians as provocative. Though neither side seems to want a complete break in relations, a prolonged period of mutual recrimination seems to be in prospect, possibly accompanied on the Yugoslav side by efforts to expand trade with the West. A reconciliation does not seem likely unless the Russians can satisfy the Yugoslavs that they are prepared to abandon the definition of sovereignty for Communist states laid down in the “Pravda” article of 26th September 1968.

43. It is unlikely that the Soviet Union would find any reliable basis for internal pro-Soviet subversion in Yugoslavia as long as Tito is in power. If his death was followed by a struggle for power among contenders for the succession, the Soviet Union might try to exploit the situation to its own advantage.

Albania

44. Albania followed the Chinese lead in attacking the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, while criticising the Dubcek regime as “capitulationist”. Albania has announced her withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact, and has made tentative moves towards an improvement of relations with Yugoslavia. There is no reason to believe that Soviet policy towards Albania will change, or that Albania’s pro-Chinese alignment will alter to the Soviet Union’s advantage.

THE MILITARY OUTLOOK

Basic Concepts

45. Much of the material which the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies have published in their attempt to justify the invasion of Czechoslovakia has concentrated on the alleged military threat from NATO, particularly from West Germany. Before assessing the military outlook in Eastern Europe, in the wake of the invasion of Czechoslovakia, it may be useful to look at Soviet military and strategic concepts for war in Europe and at the organisation of the Warsaw Pact.

46. In the formal Soviet view, general European war would begin with a NATO attack on Eastern Europe, followed by a rapid counter-offensive westwards by Warsaw Pact forces. Whether or not the Russians seriously attribute aggressive intentions or capabilities to NATO, the important feature of their military doctrine is the seizure of the initiative at the earliest possible moment, retaining all options open on the level of the conflict and the types of weapons used, at least at the outset. The Warsaw Pact ground and air forces would engage NATO forces on a broad front, manoeuvring swiftly and boldly, considering speed and continuity of action as the main manoeuvre assets. It is probable that in the main these tactics would be used both in conventional and nuclear supported operations, and they imply the probability of thrust and counter-thrust in great depth, with a battle zone

extending over very large areas. If the fighting is not to intrude into Soviet territory, the initial deployment of forces must be well to the west of the Soviet frontier. Thus the right to deploy Soviet forces in peacetime on the territory of the East European countries is fundamental to Soviet defence policy.

The Warsaw Pact

47. Some of the Soviet preparations and measures to fulfil these military requirements are co-ordinated through the Warsaw Pact, while others, for example, in air defence, are the subject of even more direct Soviet command and control. For the first five or six years of its existence, from 1955 to 1960–61, the High Command of the Warsaw Pact existed only as a Directorate of the Soviet General Staff, and the Commander-in-Chief was at the same time the Soviet First Deputy Minister of Defence. The Secretary-General of the Organisation held three posts: Secretary-General, Chief of Staff of the Pact’s forces and First Deputy Chief of the Soviet General Staff. During the reorganisation of the Soviet forces in 1960–61, the Main Staff of the Warsaw Pact was apparently separated administratively from the General Staff and established in effect as a “Chief Directorate” of the Soviet Ministry of Defence with responsibilities for liaison with the non-Soviet Warsaw Pact armies, for training and, since February 1966, for the co-ordination of the defence industries of the member-nations (see Appendix A

for the contribution of the non-Soviet Warsaw Pact countries to armaments production for the Warsaw Pact).

48. Although the Defence Ministers of the non-Soviet Warsaw Pact countries are Deputy Commanders-in-Chief and liaison officers of each country are attached to the Main Staff in Moscow, these are largely titular appointments, and all key posts in the military structure are in Soviet hands. All important plans and policies are Soviet, and standardisation of equipment and material to Soviet specifications contributes towards the dominant influence of the Soviet Union. In wartime, given the present structure, the chain of command would almost certainly by-pass the Warsaw Pact organisation and run from the Soviet Supreme Headquarters through Soviet “Front” commanders to the commanders of the Soviet and non-Soviet Warsaw Pact armies in the fields.

The Czechoslovak Crisis and its Aftermath

49. The Soviet military leaders probably feared, as a result of the Czechoslovak reform programme, that a serious gap in the Warsaw Pact defence structure would develop, either through Czechoslovakia’s defection from the Pact or a decline in the efficiency of her armed forces. In the first place, the Dubcek leadership removed a number of tried pro-Soviet military figures including the Minister of Defence, General Lomsky, two of his deputies, the Chief of the General Staff and the Head of the Political Directorate of the Armed Forces, and replaced them by officers whose military abilities and political reliability the Russians may have doubted. Secondly, the Soviet military authorities made specific criticisms of the performance of the Czechoslovak Army in the Warsaw Pact exercise “SUMAVA” in June 1968, and commented on the shortage of tank divisions within the force which the Czechoslovaks proposed to use for the defence of their frontier with West Germany in the event of war. There were reports that in the light of their doubts the Russians made – and the Czechoslovaks rejected – a request to station Soviet troops in Czechoslovakia. If these reports were true, the Czechoslovak refusal may have contributed to a growing Soviet belief that in spite of Czechoslovak assurances of complete loyalty to the Warsaw Pact, in the longer run Czechoslovak loyalty to and interest in the Warsaw Pact could not be taken for granted by the Soviet Union.

50. There has been a steady run-down of Soviet ground and air forces in Czechoslovakia, subsequent to the signing of the Status of Forces agreement on 16th October. The scale of reduction gives credence to Premier Cernik’s statement concerning the agreement, that the Czechoslovak forces are to have responsibility for the defence of the Western frontier of their country returned to them.

51. Although the Czechoslovak forces would doubtless fight loyally in defence of their own country, the Soviet leadership must retain some reservations as to their effective potential for offensive operations and it is clear that the Russians intend to maintain at least substantial ground forces on Czechoslovak soil. Hence their operational plans will presumably have to be reassessed in the light of the extension of their own military

commitments and of any adjustments which NATO may decide to make in its plans or deployments.

52. In consequence of the Czechoslovak crisis future proposed Warsaw Pact exercises are likely to become extremely delicate political issues. However, in the longer term, the Soviet government is likely to seek ways of establishing a better structure for the Warsaw Pact than was formerly the case. Politically the Soviet government may offer concessions to the non-Soviet members of the Pact in the field of national representation and consultation. Militarily, however, the Soviet Union may insist upon even tighter Soviet control over the East European armies, including, perhaps, increased Soviet participation at the lower levels of command (e.g. Army Group and Army) which up to now have been wholly national.

THE ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

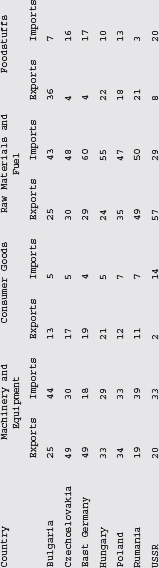

53. The effect of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia on the economic outlook in Eastern Europe may best be assessed by looking first at CMEA’s methods of operation and some of the criticisms which have been levelled against it within Eastern Europe, and then at the evidence relating to the interdependence in trade of the Soviet Union and the East European countries. The detailed figures supporting this evidence are in the Tables in Appendix B

.

The Council for Mutual Economic Aid (CMEA)

54. The basic task of CMEA – once the concept of supranational planning as put forward by Khrushchev in 1962 had been finally rejected – reverted to the co-ordination of the long-term economic plans of member countries. Specialised agencies are responsible for drawing up preliminary balance sheets of individual countries’ estimated requirements for raw materials and basic equipment over a given period, and these are discussed first on a bilateral basis and then multilaterally prior to the formation of the national plans. In the course of these consultations agreement is reached in principle on the types and quantities of goods to be exchanged between member countries in order to cover their investment and other requirements. The work of co-ordination is thus a lengthy and complex process, involving the co-operation of numerous national and international bodies. So far there are no indications of a break in the established pattern of this activity. Preparatory work has begun on the co-ordination of economic development plans for 1971–75 and at the meeting of the Executive Committee of CMEA in September 1968 (at which Czechoslovakia was represented as usual) preliminary estimates of the fuel and energy balance of member countries up to 1980 were submitted, and recommendations on various aspects of economic co-operation, including expansion of mutual goods exchanged over the 5-year period, were approved.

55. It may be that, in the post-invasion circumstances, the possibilities for making CMEA a more efficient organisation have been to some extent strengthened. Criticism of its workings had been widespread, although seldom openly voiced, for some time. Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Poland had all at various times criticised the lack of progress made in production specialisation within CMEA, the tendency being for each country to maintain a wide production range which was basically uneconomic. The divergence of views amongst CMEA members as regards specialisation spring [sic] from the differing stages of economic development of each country, and the consequent problems which they have to face. Thus, Czechoslovakia had long been pressing for a reduction in the wide range of engineering goods she produces to meet CMEA requirements, so that she could concentrate on a narrower range of highly specialised products. Poland, on the other hand, has been keen to expand her production range in order to be able to compete with the products of the more developed member countries such as Czechoslovakia and East Germany. So far a very great number of recommendations have been put forward covering production specialisation within CMEA in the fields of machinery and equipment and the chemical industry. How far these proposals have been implemented however, is difficult to assess. In general, it seems that little real specialisation has yet been achieved. Another problem which products a conflict of views within CMEA is that of pricing. Thus when an up-dated price base for goods exchanged in intra-bloc trade was introduced in 1965 the Soviet Union was severely critical of the new (lower) prices now obtaining for raw materials, claiming that the revised price-base worked in favour of exporters of machinery and equipment whilst discriminating against raw materials suppliers (the USSR is the main such supplier within CMEA). The Soviet argument was that the high costs of producing raw materials are not compensated for by the prices received from the buyers. At the same time the Soviet Union claimed to be paying world market prices for most East European machinery and equipment which was not up to world standards. A further point of issue concerned the method of settling intra-bloc payments. Some member countries, notably Poland and Czechoslovakia, have in recent years accumulated large surpluses in transferable roubles in their trade with each other. The inability to convert these transferable rouble balances into other currencies, or even – because of the general shortage of acceptable goods within the area – to offset them with additional commodity deliveries from debtor countries has led to pressure from those countries most concerned for even partial conversion of the transferable rouble.

56. Against the background of all these problems, leading economists from some of the more industrially developed member countries of CMEA – notably Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary – have for some time been suggesting various ways to improve the working efficiency of CMEA. In the past, progress on joint capital projects had frequently been halted due to the exercise by one or other member states (most often, Rumania) of the right of veto of proposals for co-production or division of production. This was based on the principle of unanimity written into the Basic Charter of CMEA, according to which all decisions or recommendations of the Council, to be binding, must have the consent of all members, and any country has the right to disassociate itself from proposed projects which it considers are not in its national interest. However, gradually the view has been increasingly gaining ground that voluntary bilateral arrangements are proving more effective than multilateral co-operation agreements dictated by CMEA. Emphasis has recently been laid on the need for wider co-operation between member countries in informing each other in more detail of their respective investment programmes, so that the coordination of investment plans for the whole area can be carried out more effectively on a long-term basis.

57. The future development of CMEA will depend to a large extent on how the Russians react to these views and trends. It seems unlikely that the Russians will agree to suggestions that the surpluses of “transferable roubles” should be made convertible. But the Soviet Union may decide that, in the longer term, the cohesiveness of the Bloc demands more attention to national economic ambitions and a more realistic appreciation of existing economic differences between the members of CMEA.

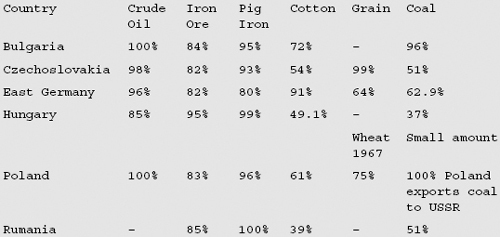

Trade Interdependence General

58. In 1967 the Eastern European countries accounted for some 56 per cent of the Soviet Union’s total trade (58 per cent including Yugoslavia). The share of the Soviet Union in the total trade of each of the six East European countries varied from over 50 per cent for Bulgaria to 28 per cent for Rumania (12 per cent for Yugoslavia). Soviet deliveries cover one-third of Eastern Europe’s import requirements for machinery and equipment, while the Soviet Union takes almost half of these countries’ exports of machinery and equipment (mainly from East Germany and Czechoslovakia). Next to machinery the Soviet Union imports from Eastern Europe mainly consumer goods – chiefly footwear, clothing and furniture. As regards raw materials, East European dependence on the Soviet Union is shown by the fact that Soviet deliveries cover East European import requirements for crude oil and pig iron by nearly 100 per cent, for iron ore by about 85 per cent, for cotton on an average by about 60 per cent, and as regards grain by some two-thirds to three-quarters for East Germany and Poland respectively, whilst nearly all Czechoslovakia’s grain imports come from the USSR (See Table V). Under the current (1966-70) 5-year trade agreements between the Soviet Union and the six East European countries, in all cases except for Rumania, the Soviet sector in these countries’ trade is planned to increase at a higher rate than their total trade.

59. Apart from trade, the East European countries and the Soviet Union are linked by numerous joint investment projects, involving two or more countries. Under these agreements machinery and equipment are supplied on long-term credit, the recipient repaying through long-term deliveries of the finished products. A recent example of this type of joint project is the Soviet-Czechoslovak oil exploration agreement. Another example is the Soviet-Hungarian agreement on aluminium, under which Hungarian

alumina is delivered to the Soviet Union for processing, and then sold back to Hungary as aluminium.

Czechoslovakia

60. Over a third of Czechoslovakia’s foreign trade in 1967 was with the Soviet Union and a further 36 per cent with other East European countries. The Soviet Union supplies by far the largest proportion of Czechoslovak imports of fuels, raw materials and foodstuffs, including practically all the country’s oil requirements and about three-quarters of her wheat imports. Machinery and equipment imports from the Soviet Union include agricultural machinery, cars, diesel locomotives and aircraft.

61. Czechoslovak dependence on the Soviet Union for supplies of basic raw materials is likely to continue, and in the case of crude oil, will no doubt increase since, under an agreement of September 1966, Czechoslovakia is to deliver on long-term credit machinery and equipment for the exploitation of Soviet oilfields, with eventual repayment in oil deliveries over a long period. Czechoslovakia has also agreed to invest, on similar terms, in the Soviet gas and iron ore industries, and will receive supplies of natural gas and pelletised ores in repayment. A switch in source of supply for such raw materials would in any case not be feasible because of the need to recoup on investments already made.

62. As regards Czechoslovak exports, machinery and equipment form about half of the total; the largest single customer being the Soviet Union. Altogether, the communist countries take nearly 80 per cent of these exports of machinery and equipment. Czechoslovakia would like to expand her machinery exports to the West – at present they form only a small share of the total – but the general quality of such goods makes them in most cases uncompetitive in Western markets. Traditional Czechoslovak manufactures, such as glassware, jewellery and leather goods have a better chance of being accepted in the West, and it is the output and sale of such products, as well as light engineering goods, that Czechoslovakia plans to promote. For advanced technology, Czechoslovakia – like other East European countries and indeed the Soviet Union – will continue to look to the West. So far there is no evidence that the Soviet Union intends to disrupt the normal pattern of Czechoslovakia’s trade with this area. It is indeed ultimately to the Soviet Union’s advantage

that not only Czechoslovakia but all the East European countries should continue to import Western technology, since this will improve the quality of the goods these countries deliver to the Soviet Union.

Poland

63. About a third of Poland’s trade is with the Soviet Union and a further third with other East European countries. Poland differs from her East European neighbours, Czechoslovakia and East Germany in that the structure of her trade relations with the Soviet Union shows a greater diversity in both imports and exports. Not only does Poland export industrial and engineering products, especially ships, to the Soviet Union, but she is the Soviet Union’s main external supplier of coal and coke. In exchange, the Soviet Union sends Poland vital raw materials such as oil, pig iron and iron ore and a variety of machinery and equipment. Like other East European countries, Poland would like to increase her trade with the West, but her ability to compete in Western markets is a limiting factor. About one third of her trade is with non-Communist countries (a considerably higher percentage than for Czechoslovakia); she became a full member of GATT in 1967, but it is too soon to assess the effects of her membership on her foreign trade.

East Germany

64. East Germany has the highest total trade turnover of all East European countries and conducts three-quarters of her trade with these countries. She is the Soviet Union’s chief trade partner in East Europe. Complete industrial plants, especially chemical plants, are a major feature of East German exports to the Soviet Union and in exchange she receives raw materials, particularly crude oil and iron ore, and foodstuffs. The Soviet Union makes up most of her deficiencies in raw materials and foodstuffs, and these together with military supplies and small amounts of machinery and equipment, make up the greater part of Soviet deliveries to East Germany. There is no doubt that imports from the Soviet Union have provided the main basis for East Germany’s recovery and growth. Czechoslovakia and Poland are her other main suppliers in East Europe; from Czechoslovakia she receives machinery, industrial consumer goods and certain industrial materials, while Poland sends large amounts of coal and some foodstuffs and machinery. East Germany has a

high level of trade with West Germany, particularly in the more specialised varieties of iron and steel products which are unavailable or scarce in East Europe.

Hungary

65. Hungary’s economy is very dependent on foreign trade, since she has few resources of her own. Over two-thirds of this trade is with East European countries, of which the Soviet Union accounts for nearly half. In the current five-year period Soviet-Hungarian trade is planned to increase by some 50 per cent. Nearly all of Hungary’s imports of crude oil, iron ore and crude phosphates come from the Soviet Union. She also receives the greater part of the machinery and equipment she needs from the Soviet Union and the other East European countries, though she has been notably increasing her purchases of Western equipment in recent years. Hungary’s exports to the Soviet Union include machinery and engineering products, particularly chemical plants and telecommunications equipment, and large quantities of alumina which are processed in the Soviet Union and sold back to Hungary in the form of aluminium. Pharmaceuticals are also an important export to the Soviet Union.

Rumania

66. Of all East European countries, Rumania is least dependent on them in her foreign trade. Only about half of her total trade is with East European countries, of which the Soviet share is 28 per cent. Credits to Rumania from NATO countries are higher than those extended to any other East European countries except the Soviet Union. Imports from the Soviet Union are lower than for any other East European country; they include raw materials, especially coal, iron-ore, ferrous and nonferrous metals, and machinery and equipment. Rumanian exports to the Soviet Union consist mainly of plant and drilling equipment for the Soviet oil industry. Within CMEA Rumanian participation is on the basis of national interest; e.g. Rumania does not belong to all the CMEA-sponsored agencies. If Soviet economic sanctions were applied to Rumania, the economy would certainly suffer in the short-term, particularly in the industrial field dependent on Soviet ferrous and non-ferrous metals and on Soviet machinery and equipment. In the long term, however, she would be able to buy these and other goods from the West, depending on her ability to expand exports to

the West; of the goods currently exported to the Soviet Union, agricultural products, wood and oil products could probably be easily marketed in the West, while machinery and equipment could be sold to the underdeveloped countries. The Soviet Union would also encounter difficulties if relations with Rumania were severed; in particular, oil-well drilling equipment, oil refinery equipment and steel pipes would be difficult to replace, at least from within Eastern Europe.

Bulgaria

67. In foreign trade, Bulgaria is extremely dependent upon the Soviet Union, both as an outlet for her exports (notably machinery and equipment, and light industrial goods) and as a supplier of capital equipment vital to the implementation of Bulgaria’s economic plans. In addition, the Soviet Union is the main supplier of a number of key raw materials, and has granted Bulgaria very large credit facilities, mainly for the development of large-scale enterprises. Although Bulgaria’s trade with the West has increased appreciably in recent years, she still has difficulty in making competitive any commodities but her foodstuffs.

THE IMPLICATIONS FOR EAST-WEST RELATIONS

68. The invasion of Czechoslovakia has increased the uncertainties about Soviet actions and the situations in which the Russians would be prepared to use force. On the whole the invasion was a move to maintain what they saw as a desirable status quo, but subsequent developments in Eastern Europe could lead them to use force again, perhaps in more dangerous circumstances, and for ostensibly the same motives. Soviet policy in other areas will be governed as before by other factors e.g. the circumstances of the situation, the Russians’ own capabilities on the spot, and the likelihood of a direct confrontation with the United States.

69. There is no reason to believe that the Soviet action in Czechoslovakia has in any way diminished the Soviet leaders’ determination to avoid nuclear war and a direct challenge to the United States or NATO. But the policies they may decide to follow could lead them into situations leading to a confrontation with NATO. This does not mean that the appearance of Soviet divisions where Czechoslovak divisions were formerly deployed indicates an intention to initiate hostilities in the NATO area. Nevertheless a higher proportion of the Warsaw Pact forces available for rapid action against the West will be Soviet, and NATO forces may have to consider the purely military effect of this on their plans.

70. Negotiations with the United States on political and defence matters in which both sides have lasting interests, such as the Non–proliferation Treaty and the proposed discussions on limiting strategic offensive and defensive weapons, will probably proceed on a strictly practical basis. The Russians will also be anxious to pursue trade and other East-West contacts in a “business as usual” atmosphere, although thanks to the popularity won by the Czechoslovak reform movement in Western Europe and North America, and the wide radio and television coverage given to the Russian invasion and the Czechoslovaks’ non-military resistance, the Russians may not be able to create this atmosphere in the short term as easily as they probably hoped.

71. In the main, however, the greatest upheaval caused by the Czechoslovak crisis is within the Soviet alliance itself, in the relations between the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia and the other East European countries. It is probable, therefore, that Soviet attention will be focussed very largely on the internal problems of Eastern Europe in the foreseeable future with the intention of restoring orthodox Communist rule to Czechoslovakia and ensuring that economic reform programmes there and in other East European countries are not undertaken in the kind of political atmosphere which grew up in Prague in the first eight months of 1968. The problem of the nationalism of the East European countries will continue to create difficulties for the Soviet Union. At the same time, the Soviet Union will continue to act as a super–power and her policies in Eastern Europe will not necessarily affect her ability or intentions to pursue a policy designed to increase Soviet influence elsewhere in the world, e.g. the Mediterranean area or the Middle East. In practice, therefore, the Soviet Union will strive to isolate her East European policy from her actions in the rest of the world. There should be no doubt, however, that her aim in Eastern Europe is to maintain her grip on the area as long as she can.

APPENDIX A

The Contribution of the Non-Soviet Warsaw Pact Countries (NSWP) to Armaments Production for the Warsaw Pact

Naval