People and dogs and outdoor environments seem to go together naturally. Being outside with your four-footed friend for company can be pure bliss, whether you are a dog-loving gardener or a garden-loving dog person. I don’t know of any statistics showing how many families include both a dog and some sort of garden, but the number must be enormous. With gardening given as the most popular outdoor leisure activity of American families, and dogs as the number one pet (in number of households including a dog), there have to be millions of households that combine the two. That combination should be a joy to all.

Yet what you hear most about are the problems—yellow spots in the lawn, digging in the flower beds, running willy-nilly through the borders, chewing on branches. But stop and think a minute—the dog doesn’t know these are problems. It’s all just the great outdoors, part of his turf, to him. We humans are the ones demanding everyone walk here, not there, or play only in that open space over there. So it’s our job to plan a dog-friendly garden that will accommodate your dog(s) as well as explain our garden-friendly rules to the dogs, and in a nice way, if you please.

Instilling good behavior in a dog is actually less complex than organic gardening. Just like a beautiful landscape, however, it doesn’t happen by itself. The effort you put in to lay the foundation for good behavior will pay off many times over in future problems avoided, just as proper soil preparation before planting your garden results in years of trouble-free enjoyment.

You can do a lot to further a stress-free blend of plants and animals by keeping the dog in mind when you plan and install features of your landscape. This doesn’t mean you can’t have the beautiful borders and winding paths you desire, just that you need to think about where your dog will be permitted unsupervised access, where you will be together, and if there’s anywhere the dog won’t be allowed at all. That’s what this book is all about—combining dogs and gardens. Just as no two gardens are precisely the same, no two dogs are exactly alike. So the information in this book allows for flexibility, whether talking about the gardens or the dogs.

Your needs will vary based on your particular garden style and your particular dog. So will your joys. One of my fondest mental snapshots remains my very first dog, a Keeshond, lying contentedly in the snow beneath a bush bursting with red berries, with birds darting in and out just over her head. A second picture shows her and a pet French lop bunny grazing face to face on some fresh spring grass. Though that lovely dog, Sundance, has been gone for 20 years now, those pictures remain bright in my mind. Now my current dog Nestle is imprinting his own images—sunbathing amid the lavender or tearing down the garden paths toward open space and a rousing game of chase. I enjoy my garden and even include garden art in my landscape, but nothing comes close to the beauty and joy of seeing dogs at home in the plantings.

If You’re a Gardener at Heart

If you are already a confirmed garden fanatic, down to your ragged fingernails, you’ll be delighted to find out how your experience will be put to good use in plant selection, garden design, and maintenance in creating your dog-friendly landscape. You’ll probably be surprised to learn that normal, natural doggy behavior that doesn’t appear to ft well with a garden can be redirected, retrained, or avoided so your dog and your garden can peacefully coexist. Don’t tell the “dog people” this, but believe it or not, if you’re a gardener who’s getting a dog, you’ll likely have an easier time of it than if you’re a dog owner who’s decided to garden! Bringing a dog into an established landscape lets you set the ground rules right from the start. If you do it right, you’ll encounter minimal conflict.

If You’re a Dog Person at Heart

If you are a dedicated dog lover, as evidenced by the dog toys strewn about the yard, you’ll find the garden design, material and plant selection information in this book (along with some great training ideas) can make a huge difference in your enjoyment of both your dog and your garden. You’ll learn how to lay out and plant your garden with your dog’s needs in mind. You can help your cause by observing how the dog already uses the patch of ground you now intend to claim and compromising where you can or planning on some retraining where you can’t. Putting in a garden where a dog already lives will probably be asking the dog to change some of his habits, and dogs are just as resistant to change as the average human, so make it fun for both of you by following the steps suggested here and enjoying the process together.

Doing What Comes Naturally

So what are these problems between dogs and gardens? Just natural doggy behavior that occurs in places you don’t want it to, mostly—digging, breaking things, peeing and pooping, chewing, and high-spirited running around. It’s part of what makes a dog a dog. You can enjoy life with your dog without damage to your gardens by planning for it.

Obviously, peeing and pooping have to take place but they can leave dead spots in the lawn and kill small plants. Fortunately it’s no harder to train a dog to use a particular area than it is to housetrain a dog in the first place. You just need the foresight to provide an appropriate place.

Breakage usually results from the dog being where he shouldn’t be or the plants being where they shouldn’t be. Designing the dog into, or out of, the garden helps avoid the problem of young rambunctious dogs and delicate prized plants, which don’t make a good mix. Be sure to provide a place where the dog can feel free to run around like a wild thing, and play with him there often, and you’ll avoid most of the plant damage. Any remaining problems can be solved by some garden redesign, adding a few dog-friendly amenities, maybe some fencing, and perhaps a little training.

Compromise is the keyword here. Trying to squash these “problems” entirely will likely prove frustrating for both the human and the dog, and they’re only problems because of where they’re occurring. Redirecting natural dog behavior such as random digging to a special digging pit and limiting chewing to approved chew toys will avoid some of the most common “bad” behaviors.

Breed Can Predict Behavior

Dogs are individuals. But because most breeds do come with built-in predispositions toward different activities, based on the work they were originally designed to do, it’s useful to know something about breed characteristics. Reading a good breed selection book can be helpful—try Your Purebred Puppy, A Buyer’s Guide by Michele Welton has good information on the personality and drawbacks of specific breeds. (See the Resources at the end of this book for this and other reading recommendations.)

So Dachshunds and the smaller terriers are often driven to dig because they were bred to eradicate vermin, even if that meant digging them out of their holes. If you have moles in your yard and bring home a Jack Russell Terrier, be prepared for the dirt to fly! Larger terriers might not be as likely to dig, but they might be prone to guarding behavior, running the fence or yard perimeter and barking. The barking is the more serious problem overall, with possible legal complications if your neighbors start complaining, but the constant travel along the same path will soon wear a trail into whatever landscaping you may have placed there. This behavior might also be exhibited by the “guard dogs” from the AKC Working Group, such as the popular Rottweiler and Doberman Pinscher. They may be quieter than the terriers, but they’ll be just as inclined to patrol. Others in the Working Group are the dogs who pull sleds—the Siberian Huskies, Alaskan Malamutes, and Samoyed. They present a unique challenge because they have a natural desire to see what’s over the next hill, and may dig to escape. The others in this Group—Bernese Mountain Dogs and Giant Schnauzers, for example—were bred to work more sedately in more urban settings, and may prove less of a challenge in garden design.

AKC Breeds and Groups

The most popular registry, the American Kennel Club (AKC), divides purebred dogs into seven groups.

Group I—Sporting Dogs

American Water Spaniel

Brittany

Chesapeake Bay Retriever

Clumber Spaniel

Cocker Spaniel

Curly-Coated Retriever

English Cocker Spaniel

English Setter

English Springer Spaniel

Field Spaniel

Flat-Coated Retriever

German Shorthaired Pointer

German Wirehaired Pointer

Golden Retriever

Gordon Setter

Irish Setter

Irish Water Spaniel

Labrador Retriever

Pointer

Spinone Italiano

Sussex Spaniel

Vizsla

Weimaraner

Welsh Springer Spaniel

Wirehaired Pointing Griffon

Group II—Hounds

Afghan Hound

American Foxhound

Basenji

Basset Hound

Beagle

Black and Tan Coonhound

Bloodhound

Borzoi

Dachshund

English Foxhound

Greyhound

Harrier

Ibizan Hound

Irish Wolfhound

Norwegian Elkhound

Otterhound

Petit Basset Griffon Vendeen

Pharaoh Hound

Rhodesian Ridgeback

Saluki

Scottish Deerhound

Whippet

Group III—Working Dogs

Akita

Alaskan Malamute

Anatolian Shepherd

Bernese Mountain Dog

Boxer

Bullmastiff

Doberman Pinscher

German Pinscher

Giant Schnauzer

Great Dane

Great Pyrenees

Greater Swiss Mountain Dog

Komondor

Kuvasz

Mastiff

Newfoundland

Portuguese Water Dog

Rottweiler

St. Bernard

Samoyed

Siberian Husky

Standard Schnauzer

Group IV—Terriers

Airedale Terrier

American Staffordshire Terrier

Australian Terrier

Bedlington Terrier

Border Terrier

Cairn Terrier

Dandie Dinmont Terrier

Fox Terrier, Smooth or Wire

Irish Terrier

Jack Russell Terrier (Parson)

Kerry Blue Terrier

Lakeland Terrier

Manchester Terrier

Miniature Bull Terrier

Miniature Schnauzer

Norfolk Terrier

Norwich Terrier

Scottish Terrier

Sealyham Terrier

Skye Terrier

Soft-coated Wheaten Terrier

Staffordshire Bull Terrier

Welsh Terrier

West Highland White Terrier

Group V—Toys

Affenpinscher

Brussels Griffon

Cavalier King

Charles Spaniel

Chihuahua

Chinese Crested

English Toy Spaniel

Havanese

Italian Greyhound

Japanese Chin

Maltese

Manchester Terrier, Toy

Miniature Pinscher

Papillon

Pekingese

Pomeranian

Poodle, Toy

Pug

Shih Tzu

Silky Terrier

Toy Fox Terrier

Yorkshire Terrier

Group VI—Non-Sporting Dogs

American Eskimo Dog

Bichon Frise

Boston Terrier

Bulldog

Chinese Shar-Pei

Chow Chow

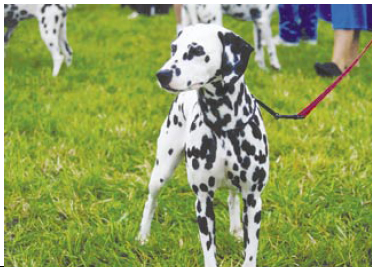

Dalmatian

Finnish Spitz

French Bulldog

Keeshond

Lhasa Apso

Löwchen

Poodle, Miniature and Standard

Schipperke

Shiba Inu

Tibetan Spaniel

Tibetan Terrier

Group VII—Herding Dogs

Anatolian Shepherd

Australian Cattle Dog

Australian Shepherd

Bearded Collie

Belgian Malinois

Belgian Sheepdog

Belgian Tervuren

Border Collie

Bouvier des Flandres

Briard

Canaan Dog

Cardigan Welsh Corgi

Collie

German Shepherd Dog

Old English Sheepdog

Pembroke Welsh Corgi

Polish Lowland Sheepdog

Puli

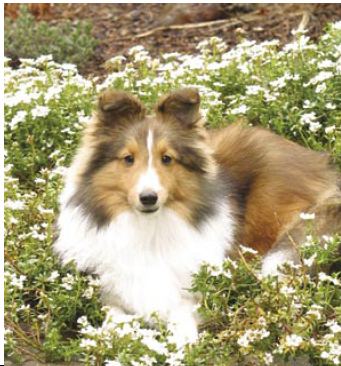

Shetland Sheepdog

The Herding Group includes some of the most high-energy dogs in the world. Herding dogs are built, mentally and physically, to move livestock pretty much all day, so don’t expect them to be lying around a small yard —it just doesn’t ft into their plans. The closer they are to their herding background (meaning a dog has been bred from working parents, who actually do herding on a regular basis), the more intent on doing their job they’re likely to be. Border Collies have been known to obsessively round up the family’s cat, children, visitors, anything they can get to move, and they’re not above nipping to get the movement they desire. An unoccupied herding dog will tend to find his own jobs to do, and few of them will ft into your landscaping plans.

Hounds come in two basic varieties, the Sighthounds and the Scenthounds. The Sighthounds are an interesting study in contrasts. Many of them come from desert climes—Greyhounds and Salukis, for example—and love to lie in a patch of sun, arranging themselves artistically amid their surroundings. Others come from northern climates and have the rough heavy coat to prove it, such as the Irish Wolfhound and the Borzoi. But all of them were bred to chase fast-moving objects, and something running by can trigger their pursuit instincts, and woe to any plants in their path. The Scenthounds, including the Bloodhound, Beagle, and various Coonhounds, rely on their noses. While many of them are relatively low-energy dogs, an enticing aroma can lead them off on the trail, with no regard for anything else. Beagles, mainly specializing in rabbit hunting, may also be inclined to dig.

The Sporting Group contains the Pointers, Setters, Spaniels and Retrievers. The highly popular Labrador Retrievers and Golden Retrievers belong to this group. Be aware that personalities will vary widely between “field” lines—dogs bred to hunt and retrieve game; “show” lines—dogs bred to compete in the show ring, and “pet” lines. Field dogs are intense high-energy individuals on a par with some of the herding breeds, and require plenty of exercise. Some of the less popular breeds, such as the Brittany or English Cocker, remain very “birdy.” They are attracted by and focused on birds, often to the detriment of obedience training and will demand lots of activity. The Retrievers, being even more mouth-oriented than the average dog, will often chew everything in sight when young. The water dogs among them may be irresistibly attracted to any water features in the yard.

Toy breeds are the compact members of the dog world. Because they are grouped solely on the basis of size, there’s no common thread on which to base personality. Some were bred solely as companions, but others are miniature versions of watchdogs or general farm dogs or even dogs designed to trot for hours in something much like a giant hamster wheel to turn meat cooking over a fire (no, I am not making this up). While their small sizes help them ft more easily into a landscape, they can be just as tenacious in their bad habits as any of their larger brethren.

Finally, there’s the Non-Sporting Group, sort of a leftover category for breeds who don’t ft any of the other groups, where again there’s no one personality type. There are Nordic breeds here—my Keeshond, for example—the Poodle (once a Sporting dog, but rarely used for such work these days), and a great variety of others, from Bulldogs to Dalmatians.

And don’t forget that other huge segment of the canine population, mixed breeds. Most of my dogs have been mixes, and I will admit that you often have to get to know them before venturing any reasonably accurate guess as to what might have gone into their genetic makeup. That shouldn’t deter you from rescuing one of the millions of dogs waiting for a home. Just study up on their most likely genetic heritage and have plans in place for how you will handle digging or chewing or any of the other basic problems, and you’ll be just fine.

Small, Medium, or Large

To move beyond the issue of breeds, size also matters, at least to some extent. A small dog can move more easily down a narrow garden path than a giant such as an Irish Wolfhound or a Bullmastiff. But the giants do compensate somewhat by tending to be less energetic. While big dogs mean bigger piles of poop, and a 150-pound dog rolling amid the daisies will inflict more damage than a 15-pound darling, other forms of damage are less related to size. Even the smallest dog can make a cratered moonscape of the yard if he sets his paws to digging. All dogs can chew, though the smaller ones may be able to reach only the lower branches. The energetic mid-size breeds such as Australian Shepherds may cause more breakage simply because they spend more of their time running around.

What it comes down to in the end is that high-energy independent-minded dogs will tend to create more problems than quieter, more compliant individuals. Breed also is no guarantee of what you will get and when it comes to mixed breeds, you will need to wait and see just what characteristics your dog will develop. Follow the Boy Scout motto and be prepared—this book will tell you how.

Your Lifestyle, Your Garden, and Your Dog

Your dog is only one side of this equation. You’re the other. The choices you make will decide how your dog and your garden get along together, and how much work will be involved in making the relationship a good one.

First off, where will your dog be spending most of her time? Our two dogs live in the house and have a dog door leading out to a fenced yard that’s only a tiny portion of our four acres. They come and go as they please, but choose mostly to be wherever the humans are. I frmly believe this is the optimal arrangement. Not only does it make me and the dogs happy, it means the majority of the landscaping lies beyond their reach, and any problems out there probably aren’t due to the dog. I understand not everyone lives on multiple acres, but I used the same system in a suburban California setting, landscaping the fenced back yard with the dogs in mind, and the front yard as the “show” garden.

Dogs are pack animals, and want to be with their family. Shutting them out not only gives them the opportunity to misbehave in the yard, it may actually encourage bad behavior. To a lonely dog, unpleasant attention (being yelled at) is better than no attention at all. So if she finds that you come running when she starts digging (or barking or knocking pots over), she’ll learn to do it more and more. You’ll be creating your own problem because you have unwittingly reinforced her bad behavior.

If you feel that your dog has to be outside, say, while you are away at work, then I strongly suggest either a fenced dog yard or a large kennel. You’ll find more information on creating a kennel to suit you both in Chapter 4. first examine your motives for keeping the dog outdoors—why can’t you use a fenced yard and a dog door and give the dog a choice of whether she wants to be in or out? I’ve heard people say they want the dog outside to guard the house. But if the dog isn’t allowed inside, why should she guard something that’s not part of her territory? Indoor dogs will bark an alert at someone’s approach, and that’s really all you want—the legal ramifications if your dog actually bites someone, even if that someone was unwelcome on your property, are enormous.

Another common reason for keeping dogs outside is that the humans are away at work all day. If your dog destroys things in your house while you are gone, you need training that’s beyond the scope of this book. The dog has either not been taught good house manners or suffers from separation anxiety. In either case, you do need to use confinement while the problems are resolved.

Housetraining problems seem to be a major roadblock to leaving dogs in the house unattended. While there are a few breeds that seem to have an inherently hard time at this, most problems result from a failure in training and can be resolved. For some excellent instructions on housetraining, see the book Before You Get Your Puppy by Dr. Ian Dunbar. Chapter 9 includes instructions for training your dog to potty in a place in the garden that you have chosen. With some time, patience, and guidance it’s a problem that can be solved.

If the dog does spend much of her time home alone, you need to provide environmental enrichment to give her something to do while you’re gone (you can find some suggestions in Chapter 4 and Chapter 9), and pay attention to her when you are at home. With today’s busy schedules, it’s easy to walk in the house, pat the dog, and then forget about her. That’s not fair to the dog, who very much wants to be part of the family. You need to provide a walk or some energetic play to burn off any excess energy that might otherwise get the dog into trouble.

Garden Designs that Work with a Dog

Your relationship with the garden also factors into how this whole human-dog-garden equation will work. People that horticulturists call “plant collectors” are probably the worst prospects for combining a dog and their garden. Their gardens feature a one-of-everything variety of plantings, and because each plant is unique, each plant is valuable to them. Damage to a single plant is viewed as a catastrophe. Best to keep a dog out of this sort of garden unless she has shown herself to be a calm and reliable companion, willing to lie in a patch of open space while her human works nearby.

Formal gardens are the next most demanding of exemplary canine behavior. Such gardens might take the form of a knot, with the beds and paths forming a curving geometric pattern of circles or “knots,” or an Italiante garden with straight lines, symmetry, and abundant garden art, or some other plan. Formal gardens rely on strong, definite boundary lines, trimmed and manicured shrubs and trees, and a strong sense of order. Damage to individual plants is not easily concealed.

Japanese gardens might be considered formal, but in a whole different way. Their plantings are based more on form than color and happily many of the evergreens and bamboos typically used stand up well to some abuse by a dog. You might want to avoid the multi-part freestanding lanterns you see in Japanese-style landscapes, because they have multiple pieces that can be knocked over by a dog. The water features typically included will be fine with dogs who disdain getting wet, but might suffer from the attentions of water-lovers. The dry Zen garden can always be re-raked, or you can choose to admire the pattern of dog prints running through the sand. Bonsai, however, should be kept out of harm’s way.

Many homeowners, not wanting to spend a lot of time in the garden, use large quantities of landscape rock of various sorts, with a few plants placed amid them. The rocks are often volcanic in origin and not pleasant to walk or lie on, and dogs will usually spend little time in such areas. If this is your style, you’ll find the design and layout information provided later useful. Be sure to include some dog-friendly spots among the rocks!

Less formal gardens are easier to blend with dogs. “English country” or “cottage” gardens rely on masses of plantings, rising from lower plants along the edges to taller plants behind, and completely covering the ground. Such solid-appearing foliage walls discourage casual trampling through the flowers, so will tend to keep the dog out (though a dog in hot pursuit of something doesn’t pay attention to thorny berry bushes, let alone flowers). Because the whole thing is a riot of different forms and colors, any damage that does occur is not as readily apparent.

Even more forgiving are wildflower meadows and naturalized woodlands. You and the dog can walk through them with minor or no impact, and really enjoy your surroundings. Many kinds of bulbs will “naturalize,” spreading over the years to form seasonal drifts of blossoms, but spending much of their time underground out of the way. Running through them while blooming may break off some flowers, but it won’t harm the plants themselves, so relax, bring the broken stems indoors to enjoy. Your attitude will be important in bringing dog and garden together.

Your garden has to suit you, of course. By planning simultaneously for your garden and your dog, you can enjoy both with fewer worries.