I am Ardeshir Mohassess. But I like to be known only with my first name. Because I like my first name a lot. I think that this is the best name that I could have been given. It is a beautiful name. Especially when I write it under, above, or in the middle of my sketches.

—Ardeshir Mohassess, in a conversation with Esma’il Kho’i

The rich and still flourishing work of Ardeshir Mohassess (born in Rasht in Northern Iran in 1938, died in New York in 2008) has been the subject of numerous solo and group exhibitions around the world, and of as many learned and insightful essays and articles.1 What perhaps most significantly distinguishes this particular exhibition of Mohassess at Asia Society from all others (in addition to coinciding with his 70th birthday) is the exceptional fact that it is curated by two other distinguished Iranian artists—Shirin Neshat and Nicky Nodjoumi. When they asked me to join them in this project and write an essay for this particular exhibition of the work of Mohassess, more than anything else I was conscious of the fact that on this exceptional occasion three groundbreaking artists—in fact three momentous events in Iranian visual modernity—have come together. What is gathered under one roof here is not just two artists’ vision of another artist’s work, but perhaps as significantly the serendipitous gathering of their creative consciousness in one historic moment that demands equal attention.

I am constitutionally suspicious of the term “exile” or (even worse) “diaspora.” If Palestinian (and now Afghan, Iraqi, and Lebanese) refugees fleeing vicious dispossession, systematic persecution, mass murder, and predatory military invasion and occupation are in exile and may form diasporic communities in ramshackle refugee camps, others may want to think twice before they place themselves next to them. Estimates suggest that a population almost the size of the United States (300,000,000) is now roaming the globe—in destitution and despair—in search of menial jobs outside their own native lands. If that staggering number of labor migration around the world has a claim on the term “diasporic communities” then others may wish to reconsider theirs. Above all, the terms “exile” and “diaspora” radically disenfranchise people from the immediate habitat that they inhabit and thus submit and presume them living a dually marginal and inconsequential life. The iconic presence of Mohassess, Neshat, and Nodjoumi (and one might add to them that of the prominent Iranian filmmaker Amir Naderi) in New York points to a rather different historical fact, a fact that terms such as “exile” or “diaspora” categorically conceals and distorts, namely the active formation of a “transaesthetics of difference”—of artists successfully inhabiting an aesthetic pace outside their homelands—that requires a far more critical take and consideration. The fact that this particular exhibition of Ardeshir Mohassess, or many of those by Neshat and Nodjoumi, could not possibly be put together in the current capital of an Islamic Republic marks the force and immediacy of their work and requires a sustained endeavor to read such works from a fresh and different angle. Categorizing them as “Iranian,” “Islamic,” “Diasporic,” or “Exilic” art constitutionally compromises their significance and distorts our manners of reading them. Neither the worldly resonances of their art nor indeed the tenor and timber of my writing on their work fits the bill for an exilic or diasporic disposition. They have done their work (and I will do mine) fully conscious of the cosmopolitan character of the worldly culture that has made us all possible.

Ours (the New York where Mohassess now called home and where he was being exhibited) is a different and differing time from the time that once gave birth to an artist like Mohassess. Ours is the time of terror, the state of war, the iconic year and ground zero of post-9/11 Abu Ghraib torture chambers punctuating the emerging societies of camps—camps of illegal immigrants and enemy combatants in Guantánamo Bay and Bagram Air Base alike. Ours is “the state of exception,” as the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben terms it. “The state of exception,” Agamben believes, “is … not the chaos that precedes order but rather the situation that results from its suspension. In this sense, the exception is truly, according to its etymological root, taken outside (ex-capere), and not simply excluded.”2 We are on the liminal line, in and out of order, the ordinary—all of us (aliens, immigrants, citizens, blue-blooded Americans) made into “enemy combatants,” the enemy within. Ours is the time of Homeland Security acts, corrosion of civil liberties, politics of fabricated fears, reign of senseless, pointless, criminal, and above all spectacular acts of vengeful violence (genocidal, homicidal, suicidal) for immediate visual effects. Ours is the time of Minutemen vigilantes haunting down Latino and Latina labor immigrants as white colonial settlers did, hunting down aborigines and kangaroos, in Australia. Ours is the time of fear—fear of immigrant communities and their leaders and intellectuals becoming increasingly criminalized, self-conscious, provincialized, degenerated into self-loathing spies and native informers misinforming their employers against their own people. Ours, in short, is the time of the mutation of free, democratic, worldly, and cosmopolitan cultures (of the sort that once made Mohassess possible) into parochial ethnicities transmuting their own arts and cultures into matters of anthropological curiosity for their host countries. This is a vastly different world from the world of Mohassess’s learned mother, Sorur Mahkameh Mohassess, an educator, a gifted poet, a respected literary figure and a vastly learned woman who was chiefly responsible for the early literary education and aesthetic cultivation of her son, who would soon become a world-renowned artist.3

If Mohassess, Neshat, and Nodjoumi have come together to rethink the artistic legacy of a worldly visionary who is one among them (and one among many more like them), more than anything else, it is imperative to recall the cosmopolitan culture that once gave birth to them all—a past so recent that one can just turn the page of history and read it, and yet a past now seemingly so distant as if it never was. “Only in New York,” a wise and learned friend and colleague of mine is always fond of saying, “people eat Indian or Chinese food. In India and China people don’t eat Indian or Chinese food. They just eat food.” In Iran too—in Iran Mohassess was not an Iranian artist, or a Muslim artist, he was, and he is, just an artist, an artist located in the crosscurrents of his history, born and bred to a worldly culture deeply conscious of its cosmopolitan disposition. Before museums of modern curiosities have turned Mohassess (and other artists like him) into an object of anthropological observation, he will have to be seen the way he saw himself—and with him must also be seen the world that in him saw the parameters of its own critical self-awareness, of its cosmopolitan character and culture.

The cosmopolitan worldliness that once gave birth and breeding to Mohassess has a history, a pride of place, an aesthetic point of reference. Mohassess is the child of post-World War II (1939–1944) Iran, carrying in his creative consciousness the overcrowded historical memories of two monarchies he has survived (the Qajars and the Pahlavis), a theocracy he has escaped (the Islamic Republic), and now an Empire he calls home (the United States). Born in 1938 in Rasht in the Caspian province of Gilan, during its occupation by Russian forces, he grew up very much in the shadow of the post-Constitutional period (1906–1911) politics and culture, when the national aspirations of Iranians were squarely under the influence of the two colonial superpowers of the time: The Russians and the British.4 The Iran of Mohassess’s parents, the transitional period of 1910s to 1930s, as the last Qajar dynasty was fading out and the Pahlavi monarchy was fading in, was divided between two spheres of influence, the North under the Russians and the South under the British. Mohassess’s father, Abbas Qoli Mohassess, was a judge and his mother, Sorur Mahkameh Mohassess, a prominent educator, poet, and literary figure. Mohassess has always singled out his mother as having had an early and enduring influence on his sensibilities and cultivation as an artist. She was a renowned poet and as a close friend and confident of the legendary poet of her time Parvin E’tesami. The generation of social and moral consciousness that Sorur Mahkameh Mohassess represented was very much the result of the Constitutional Revolution (1906–1911) and the wave of groundbreaking sensibilities that it ushered into the normative foregroundings of the nation at large.

Mohassess’s childhood in the 1940s was overshadowed with the military occupation of Iran by the Allied Forces during World War II (1939–1944), and the paradoxical period of freedom that this occupation had occasioned, a period in which a range of revolutionary socialist, anticolonial nationalist, and militant Islamist movements had divided the political loyalties of the young nation, scarcely emerging out of its medieval slumber. This is the time when the brutal tyranny of Reza Shah Pahlavi (reigned, 1926–1941) and his flirtations with Adolph Hitler gave in under the invasion and occupation of the country by the Allied forces and yielded power to the fragile rule of the young Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi (reigned, 1941–1979). In this environment, Mohassess attended a nursery school whose principal, a certain Ms. Jamileh, was a renowned Marxist and had spent years in the Pahlavi prison. At the age of seven, Mohassess recalls having done his very first painting—that of a fearful general.5

Mohassess’s youth in the 1950s was marked by the national trauma of his country at large when in 1953 the young and impressionable Mohassess, now only fifteen years old, witnessed the CIA-engineered coup that dismantled the democratically elected government of Mohammad Mosaddegh and brought back Mohammad Reza Shah to power. Iran as a nation would never recover from the trauma of the CIA-sponsored coup, and with that single act of treachery an entire generation of Iranian intelligentsia, literati, and artists became ipso facto political—though political in far more enduring and epistemic terms than a mere ideological proclivity toward progressive and anticolonial politics. Mohassess’s teenage years were spent in Tehran, where his parents had moved and where he attended a number of different high schools. At about age eleven and twelve, Mohassess’s work began to appear in Towfiq, a leading satirical journal.

By the time Mohassess received his undergraduate degree in political science at Tehran University in 1962, and began publishing his work in national periodicals in the following year, despite his youth he had the active historical memory of a constitutional revolution, the colonial domination of his homeland by the British and the Russians, a change of dynasty, a military occupation by the Allied Forces, a massive social uprising for political liberty, all dashed out by a vicious military coup engineered by American and British intelligence forces. By now Mohassess was emerging as a major artistic force in his homeland. In 1963, Jalil Ziapour published the first major article on his work in Ferdowsi, the leading literary and political organ of the period. The exhibition of his collected work in Qandriz Gallery in 1967, and subsequently the publication of a major retrospective of his work (1961–1966) by the leading literary periodical Daftar-ha-ye Zamaneh established Mohassess’s reputation as a major force in Iranian visual politics.6 That politics had a history, a poetry, a literature, a music—and now in Mohassess’s generation of visual artists also a palpable visibility.

If the 1940s was defined by the revolutionary socialism that was evident in the formation of the Iranian Tudeh (Communist) Party in the immediate aftermath of the Allied occupation of Iran, and the 1950s by Mosaddegh’s anticolonial nationalism that ended in the CIA-sponsored coup of 1953, the 1960s was dominated by the militant Islamism that came to an abrupt culmination during the June 1963 uprising led by Ayatollah Khomeini. The publication of subsequent collections of Mohassess’s work—those of 1967–1971, and then another in 1972—is a crucial marker of the turmoil that followed the Islamist June 1963 revolt and a decade after that the Marxist Siahkal uprising of 1973, which became the defining moment of the 1970s that ultimately led to the downfall of the Pahlavi monarchy. Soon after the brutal Islamization of the 1979 revolution, Mohassess left his homeland and came to the United States, and here his principal preoccupation with the atrocities of the Islamic Republic throughout the 1980s began, gradually, to mingle and meander with the politics of his adopted country and the globalized imperialism of the Ronald Reagan and post-Reagan eras. From this point forward, the historical memories of three successive political regimes—the Qajars, the Pahlavis, and the Islamic Republic—enter Mohassess’s critical engagement with the imperial politics of his new habitat, linking the post-Vietnam Syndrome of the Reagan era (1980–1988) to the New World Order of the first President George Bush (1989–1993), the rise of neoliberal economics during the administration of President Bill Clinton (1993–2000), and finally to the neoconservative takeover during the presidency of the second President George W. Bush (2000–2008). As a new immigrant to a land and a politics that beginning in 1953 had robbed his homeland of its mere chance of a democracy, Mohassess is now the self-conscious subject of a globalized empire—an Imperium that paradoxically lacks the geographical imaginary and the cosmopolitan culture that have always underlined Mohassess’s visual politics, an imperial imaginary that true to its pugnacious parochialism reduces all worldly cultural artifacts to totemic tribalisms of one clannish constitution or another. The creative elegance and aesthetic sublimity of his art are worlds and galaxies apart from the anthropological provincialism that now defines the curatorial curiosities of North American museums when it comes to worldly cultures and their works of art. To see the moral rectitude, ethical authority, and aesthetic modernity at the heart of Mohassess’s visual vocabulary, and thus to place his art in the middle of a hermeneutic circle that once defined the cosmopolitan culture of his birth and breeding, we need to re/imagine him within the critical apparatus and the creative consciousness that first perceived and received him.

The expansive cosmopolitanism of Mohassess’s art is today homeless at the height of its worldliness. It is not at home here in the United States, where a predatory empire ethnicizes every cultural artifact it touches and transforms it into an anthropological object of curiosity. Mohassess’s art is not at home in his own homeland either, where a radically totalitarian Islamic Republic has all but successfully repressed and incarcerated the thriving cosmopolitan culture that once occasioned, embraced, and celebrated Mohassess. The militant mutation of the United States from a republic into an empire, and the simultaneous degeneration of Iranian cosmopolitan culture into an Islamist nativism force the planet into an imbalance of power where the world forecloses its own worldliness. The more this predatory empire becomes globalized the more it becomes provincial, parochial, myopic, and mendacious in its own character and culture, and thus the more it radically sees the world in its own image and degenerates worldly cultures into ethnicized curiosities, posing hostilities, objects of observation and derision at one and the same time. The disease is contagious and the world that it afflicts becomes incessantly more tribalized—pitting a Hindu fundamentalism here against an Islamic Republic there, a Jewish state somewhere else, and a Christian empire over them all: And all of them against the worldly and cosmopolitan tolerance of a globe otherwise set to destroy itself. If anything at all, Mohassess is the product of that critical consciousness that saw the world from the cosmopolitan angle of a democratic vision that had room for every creed and privileged none.

If not at home in New York of post-9/11 syndrome, and of George W. Bush’s War of Terrorism, and if not at home for sure in the capital of an Islamic Republic of fear and fanaticism, then where was Mohassess ever at home? Where can one begin to recall that worldly, cosmopolitan, culture that once embraced and celebrated Mohassess? At the height of his critical alacrity and artistic achievements, Mohassess first and foremost will have to be placed in the context of the visual modernity that once embraced and celebrated him. There is a revolutionary lexicography behind Mohassess’s visual vocabulary that is deeply rooted in the syntax and morphology of that visual modernity, and without it one will never learn how to “read” his pictures.

There are few historic moments more appropriate to delineate that emancipatory cosmopolitanism than when that visual modernity met its poetic match. At the height of his illustrious career, in 1973, four different collections of Mohassess’s work appeared in Iran and Europe. To two of these four collections two prominent Iranian public intellectuals, a celebrated poet (Ahmad Shamlu) and a renowned artist (Aydin Aghdashloo), wrote laudatory introductions. Shamlu’s introduction to Mohassess’s Current Events (1973)7 and Aghdashloo’s introduction to Mohassess’s Ceremonies (1973) mark the zenith of the young artist’s reception by the critical and artistic communities of his time. Shamlu (1925–2000), the leading Iranian public intellectual and modernist critic, was by then the poet laureate of his nation at large, and Aghdashloo had also by then established himself as one of the most celebrated artists and critics of his generation. Between Shamlu and Aghdashloo, the literary and artistic establishment of the country had embraced Mohassess as an artist gifted with the assiduous talent of a deeply disturbing gaze into the grotesque peeking out of the ordinary. No one before, after, or other than Mohassess had quite in the same way tapped into the uncanny presence of the grotesque in the heart of the everydayness. There was an ordinariness, a mere matter of factness, to and about Mohassess’s grotesqueries that at one and the same time frightened, amused, and bewildered people. He was more than political in his work. He was cosmic, metaphysical, virtual in his vision—in just a few short strokes he was able to capture the contorted soul of a people, a nation, a world. He frightened people into thinking they were entertained and amused.

To understand the significance of this year and such endorsements in the artistic career of Mohassess, we need in fact to shift gear and consider another important event of 1973. In this year, Iran Darroudi, a celebrated Iranian artist, published a collection of her paintings in Tehran.8 Among the introductory essays and commentaries by a number of prominent French and Iranian cultural critics (among them Andre Malraux and Jean Cocteau), she had also included a poem by Shamlu. A poem by Shamlu was by far the most persuasive (and prestigious) endorsement that an artist of a visual medium could hope for to come from the poet laureate of the nation. This poetic endorsement is one of the few critical moments when a leading Iranian poet has reflected on a visual medium otherwise incorporated (indeed appropriated) into the varied vagaries of poetic imageries.9 The encounter between Shamlu’s poetry and Darroudi’s painting marks a crucial rendezvous between Iranian poetic and visual modernities—for at this juncture, Darroudi’s vision had entered Shamlu’s poetry, and, vice versa, his poetic parabolics entered her visual vacuities. Dwelling on this metamorphic moment is one (among many) crucial way through which we can cut a quick tunnel to the cosmopolitan worldliness and the aesthetic modernity that once embraced Mohassess and his contemporaries. In the Iranian context, Shamlu’s poetic dwelling on Darroudi’s painting is tantamount to, say, Heidegger’s philosophical reflections on Hölderlin’s poetry—a crossing of the line, a cross-metaphorization of signs and sounds, a metamorphic moment when two passing stars collide to generate an infinitely brighter light. My turning to Shamlu’s poem to invoke the aesthetic modernity that at once made Mohassess possible and then celebrated him is to theorize that aesthetics from the heart of its palpitations, for as I have always held our poets were our theorists.

This is how Shamlu begins his poem:

The reference here is obviously to Persian (so-called “miniature”) painting and to the unexpected appearance of a tree or an animal that materializes from the shapes of rocks or vegetation in the painting. The critical moment is thus staged so that Darroudi’s art will have a visual history against which Shamlu will have her revolt. “Persian Painting,” as a category, a constitutional claim, an historical legacy, is here staged and dismissed at one and the same time in order to clear the way for a different kind of painting, very much indeed as the way Shamlu’s own poetry (predicated on Nima Yushij’s) was catapulted against the mighty fortress of medieval Persian poetic weight.11 In Shamlu’s visualization of Darroudi’s painting, the poetic voice and the aesthetic vision are instantly paired and thematically interlaced. This is a particularly critical point in the creative act that constitutes an art as having emerged from the aesthetic modernity of a people (thus having become a nation) because we are witnessing a rare interface between the sight and the sound of that creative imagination—the grammatology, in fact, of Iranian poetic and visual modernity.

Shamlu proceeds with this reading of medieval Persian paintings:

For those who know Shamlu’s taste in (an éngagé, progressive, and iconoclastic) art it is quite evident that there is a biting sarcasm and dismissive attitude in this stanza. Painting deer and sheep in the middle of nowhere and to no particular avail is not Shamlu’s ideal of art. The critical point here is the relevance of a work of art, its material location in its culture and economy of production—of material life itself—forming the formalism and informing the thematic energy of the work of art. Here, Shamlu speaks with the voice of a critical consciousness rooted in the material basis of a culture that demands relevance not so much for a cause, an ideology, or a movement as for how is one to see and read a creative act. When a medieval Persian painter sits in his atelier and illustrates a manuscript with a narrative painting obviously we are witnessing a crucial creative moment of that culture. But the subject and the audience of that creative act remain limited to its immediate constituency, the courtly milieu, the sight of power—and thus the very citation of tyranny. In Shamlu’s poem we are in effect sending a familiar, though revolutionary, poetic invitation to a visual event to enter a critical moment of Iranian historical self-consciousness. Visually, in other words, a moment of aesthetic rupture has occurred, Shamlu has noted it, and he is now embracing and placing it into a larger sight and site of critical response. He is extending his own poetic rebellion against tyrannical prosody into a visual defiance against aesthetic irrelevance to history. This is no longer what used to be called “committed art.” This is re-imagining the aesthetic terms of material history, re-thinking the semiotics of a different manner of seeing the world, its formal destruction, formative re-invention.

The sarcasm, now feeding on a noble anger, becomes even more evident in the next stanza:

Fat and with a belly full of food, painters and poets drawing and describing hungry beasts is a quickening trope quite familiar in the Iranian éngagé art of the 1960s and 1970s. Court poets and painters making their living out of entertaining their princely patrons was in sharp contrast to the sort of artists and arts that the brutal realities (destitution and anger) of Shamlu’s generation faced and addressed. What is crucial here is that it is not just Shamlu’s poetry that is becoming ever more politically pronounced, but that Darroudi’s painting and Shamlu’s poetry, in their cross-mutation, are approximating each other from an isolated social irrelevance into a larger material force. Shamlu’s poetic voice and Darroudi’s aesthetic vision interlace and embrace each other into a rare moment of reification where poetic voice and aesthetic vision notice, note, and register each other. This is all by way of an historical prelude and background against which Shamlu now places Darroudi and her art (and with her art defines the defiant parameters of an entire spectrum of aesthetic modernity, which in turn artists like Ardeshir Mohassess carry to their rhetorical conclusions):

This is now Shamlu talking: the poet laureate, the most eloquent voice of a collective conscience, the princely pride of a whole generation of poetic protest, our subject reconfigured, liberated. The poet talking to the painter: “You, though, draw the lines/Of similarity.” There is an abiding sense of command to Shamlu’s imperative: to khotut-e shebahat ra tasvir kon! A sense of critical awareness, a sharing of self-transformative sentiments, one in words reflecting the other in vision, now brings the poet and the painter together. Shamlu’s ah-o ahan-o ahak-e zendeh—which I have translated as “sigh, steel and cement,” in the remote hope that I can echo Shamlu’s alliteration with “ah” (“sigh” in Persian) in the “s” sound of “sigh,” etc.—is directly out of his political awareness of the real: sigh of disappointment, poverty, and defeat, steel of city life, urbanity, factories, workers and revolt, cement (ahak is actually the powdered lime stone used in masonry, but for obvious reasons I have opted for cement) of factories, buildings, urbanization, coarse and cold realities. These items (either as words or as visions) have never been part of a painter’s palette or a poet’s vocabulary. By using them verbally, Shamlu recommends them visually. The same is with “smoke, life and pain,” which in the original reads much better in its alliteration with ‘d’ in “dud-o dorugh-o dard.”

By the time that Shamlu announces: “For dark silence/Is not among our virtues,” there remains no doubt as to the symphonic crescendo of his intentions. The expression I have had to translate as “dark silence” is crucial here. The word in Persian is khamushi, which is both “silence” (absence of voice) and “darkness” (absence of vision). We remain khamush, that is “silent,” and we khamush, that is “turn off,” a light, thus “darkness.” So in this very exquisite, and very strange, word we have two simultaneous erasures of sight and sound, vision and voice. It is precisely in this word, khamushi, that Shamlu lends his poetic voice to Darroudi’s aesthetic vision, and thus brings the two into a singular, though bi-focal, perception of the real. They both, Shamlu recommends, cannot be either a painter of invisibility or a poet of silence. They must be a painter with a vision and a poet with a voice. The desperate times demand it. But this fusion, and the poetics of voice and vision it implicated, was no mere political necessity. It had ipso facto, in and of itself, constituted an aesthetics of relevance and urgency far beyond any political particulars.

The rest of Shamlu’s poem continues with this double-intention on visuality-verbality, painting-poetry, marking a particularly powerful bi-focal synchrony in Iranian aesthetic modernity. Shamlu offers a succession of alternatives in sight and sound:

Shamlu’s choice obviously is, and recommends them for Darroudi to become, the “cry of thirst” and “the victorious uproar of famine.” But water to drink and wheat for bread are not just the staples of a simple life that Shamlu’s poetry invokes for the living condition of millions of disenfranchised people that would soon gather like a storm around a revolution. The very same tropes and metaphors are also the proportions of a tabula rasa on which Shamlu is inscribing the “biblical” narrative of a new dispensation of his nation’s claim to peoplehood, nationhood, dignity, and purpose. But here in sound and soon in sight (because immediately after this poem comes the collection of Darroudi’s paintings) we are incessantly bringing together two previously separated sensations in seeing and sounding. That poetic fusion of sight and sound is now definitive to an aesthetic modernity, at the heart of a cosmopolitan culture, that had learned how to read, watch, and celebrate an iconoclastic artist like Mohassess.

In Shamlu’s poem, we soon run into yet another mixed metaphor that collapses the sight and sound together:

On the surface of it a strange metaphor, a mixed metaphor, and precisely so: “silence of the sun” (“sokut-e aftab”) is Shamlu’s way of approximating his voice and Darroudi’s vision together, speaking in her vision, having her see with his voice. The sun of course cannot be silent, and even if it could its silence would not be darkness. It is the absence of the solar light that darkens the vision and blinds. But in his poetic voice, Shamlu in effect restores vision to Darroudi’s sight: A miraculous (evidently melodic, and suggestively erotic) dance between a masculine voice and a feminine sight. Darroudi here enables Shamlu to see and Shamlu leads Darroudi to sing. And it is in that song and sight that a rare moment of clairvoyance is experienced by a culture otherwise blinded to the sign, because it is too fixated on the signifier, too oriented toward the signified, too frightened by the Transcendental Signified.12

Iranians, as the inheritors of an overwhelmingly literal and literary culture, have succeeded far more in shattering the word in their poetry than projecting its signification back to the unsettling sign. Iranians are far better poets than painters. Historically. For every ten poets we have celebrated we have not produced one painter, even to condemn, for every one hundred books written not one picture, even to burn. We are far more verbal than visual. Even the pictures we have produced we have anchored their visual freedom to books as illustrations in manuscripts. We have textualized them, deposited them safely in the protective custody of books. We have been forbidden to paint. We have revolted poetically: Tried to see with our mind’s eyes, in trembled words, as they remember their forgotten and repressed signs.13

Right here in Shamlu’s words, upon the premise of a mixed metaphor that collapses sound and sight, approximates the ear and the eye, he has taught us, over a poetic career that has expanded over half a century, how to train our ears to see the shining force of one conclusion of his vision:

How is a painter to paint a cry? Unless the brush can sing, or the eye listen.

A lost dignity restored, a place regained. To the conquest of—not land, governments, or throne, but of—the very simple f/act of being, tyranny defied and humiliation rejected, the poet commands the painter, and the painter shows the way. Then comes the final confession and then the command:

Exactly in the same year (1973) that Ahmad Shamlu composed his poem about Darroudi’s paintings, and the visual and poetic terms of an aesthetic modernity were now in the active imagination of their audience, another prominent Iranian poet, Esma’il Kho’i, wrote, though this time in his hallmark halting prose, about Mohassess, by then already the most boisterous drawing pen in the country. Mohassess had exploded on the Iranian scene of the 1960s with an uproarious proclamation, the most rambunctious vision of the cultural roots of tyranny. His pen was clamorous, his drawings noisy, his pronouncements obstreperous. When Kho’i published his Shenakht-nameh-ye Ardeshi-e Mohassess (“An Introduction to Ardeshir Mohassess”) in 1973, the subject of his admiration was already a prominent visual critique of his culture. Kho’i detected in Mohassess’s visceral critique a visual reflection of his generation’s poetic revolt against lie and hypocrisy.

How come, [Kho’i asked in his characteristically broken prose] and why is it exactly, that Ardeshir, Ardeshir the brave, the breathtaking master, matchless in Iran, in the world with very few peers, is only and always busy breaking up aspects of evil, ugliness, and lie, and never and at no time does he so in praising the good, the beautiful, or the right?”14

In this groundbreaking major essay on Mohassess, Kho’i praised the young artist as an “Enemy of Lies” and engaged in a piercing review of the social and cultural circumstances that had necessitated his art. Kho’i was a student of philosophy and his reading of Mohassess was geared toward a principled recognition that “what we are concerned with is the very form of man’s existence. And the form of man’s existence is yet to be realized.”15 We are, in other words, in a course of discovery seeking to realize our formal presence in the world, and Mohassess’s vision was to approximate us toward that goal, as indeed it was Kho’i’s own poetic task, and the task of the creative imagination he best represented. “Whenever I look at a sketch or a picture done by Ardeshir, I feel the same pain, wonder, and anxiety that Zoroaster must have experienced in that painful, astonishing, and fearful moment when he realized the absolute nakedness of his own soul.”16 The anxiety had to do with Kho’i’s conviction that art generated two kinds of questions, one before it is understood and the other after it is thus located and theorized. Kho’i’s own concern was with the latter, when a work of art had generated moral questions in need of responding. There is a here-and-now-ness about Mohassess’s work, Kho’i believed, that marked its significance, a here-and-now-ness that distinguished all works of creative conscience at odds with the predicament of a culture.17 From this premise Kho’i then concludes that Mohassess is a global artist precisely because of being so thoroughly rooted in his local history.18

Kho’i then proceeds to give an account of a conversation that he had with Mohassess. At the very outset, Kho’i uses a mixed metaphor that echoes Shamlu’s poetic reflection on Darroudi. In praising Mohassess’s work, Kho’i suggests that “although you speak with lines and pictures and I with words and phrases, … I consider you my comrade in arms.”19 Mohassess of course does not “speak” with his images, and there precisely is the colliding explosion of poetic verbality and aesthetic visuality with which this generation of poet/painters were deeply engaged. We see a similar reflection, when Kho’i asks Mohassess who he is. Kho’i means it in a more existential sense. But notice how Mohassess turns it into a visual response:

I am Ardeshir Mohassess. But I like to be known only with my first name. Because I like my first name a lot. I think that this is the best name that I could have been given. It is a beautiful name. Especially when I write it under, above, or in the middle of my sketches. There is a disposition full of vertical rectitude about it. In my early work I used to sign my name very cautiously. I was trying to make my name come out beautifully. But I failed. Occasionally, when I was very young, I would even ask my mother to sign my name. Because my mother has a beautiful handwriting. But now, without the slightest hesitation, precision, or anxiety, and with full confidence, I sign my name. I think that it is a beautiful signature. Although it is said, and rightly so, that the rules of beautiful calligraphy are not observed in it. The dots are sitting with too much space above and beneath the letters.20

This active cross-mutation of the name as the Signifier pointing to a person into the shape of its Sign becoming part of a picture has a critical echo toward the end of the interview between the poet and the painter. Kho’i summarizes and concludes his view of Mohassess’s work by suggesting that “I believe that by showing us the most wicked parts of evil and lie you want to direct us, the anxious audience, towards the good, the beautiful and the right. You destroy in order to re-build.”21 The Persian phrase that Kho’i uses here and I translate as “anxious audience” is a critical phrase. Negarandegan-e Negaran does indeed mean “the anxious audience.” But if you know Persian, you immediately recognize that in the term negaran there is a double dwelling on the term negar, which means “to look.” The word negaran means both to look at something and to worry about it. Negaran is in active participle mood. When you are negaran you worriedly look for something, as in looking expectantly at a road or a door or through a window for someone to arrive. Thus there is an active interjection in the word negaran between looking and worrying. This active identification of vision with anxiety, already embedded in the language, is at the heart of Mohassess’s visual mutation of his overtly verbal culture. To move toward visuality, Mohassess’s generation was prepared by the already accomplished poetic shattering of the word which had made the visual encounter with the naked face of the Sign (“Ardeshir” not as a name but as a shape) not only possible but necessary for that final moment of emancipation.22

By the early 1960s, when Mohassess’s visual critic comes to full fruition, we are at a crucial turning point in the Iranian creative consciousness in both aesthetic and moral terms. The poetic shattering of the word now radically shakes the textual authority of the verbal culture and it is now subjected to a visual sublimation. Persian poetry has always had a critical slant toward the Iranian culture at large. Even in its most compromising moment when it has been put squarely at the service of the medieval court, poetry has in its formal defiance of the prose foregrounded a moment of critical pause. But a wider look at the spectrum of the Persian poetic practice, in its lyrical (Ghazal), contemplative (Ruba’i), and gnostic (Mathnavi) moments, reveals both a formal and a substantive critical stand that has broken loose through the tight grip of the textual authentication of the culture-in-practice. Add to that formal and substantive breaking up of the word, the maternal Persian poetic pause interjected against the paramount presence of the paternal Arabic of the Muslim Sacred Text.23 The result is a highly critical poetic cessation that balances the very autocratic diction of Persian prose.

Visualizing the verbal back from the domineering domain of Signification into the site and sight of the Sign via the poetic shattering of the word is where the Iranian counter-culture of the 1960s rested its case in an aesthetic modernity that sought to restore agency precisely through a formal defiance that Esmail Kho’i had detected in Mohassess’s work. Here the modernist poetry that Shamlu and Kho’i best represented, the cinema of Daryush Mehrju’i and Bahram Beiza’i (among many others), the fiction of Houshang Golshiri and Mahmoud Dolatabadi, and the vast spectrum of a visual art that ranged from Aghdashloo and Darroudi to Mohassess and Nodjoumi all came together to create a vast and self-generating ocularcentricism that gave a new lease on life to pure and undiluted formality of the Sign. The political nature of this counter-culture need not be overemphasized, nor indeed should it be underestimated. The fabricated battle between “Tradition and Modernity” that has plagued the post/colonial world remained a constitutionally textual battle, further aggravating the verbality of the battle and its protagonists. The ideological constitution of both the Islamic and the Iranian, in religious and nationalist directions, further consolidated and authenticated a textual claim on the credulity of a singular constituency. But the project of the colonially mitigated European modernity was equally textual in its claims to authenticity, the forefathers of the Enlightenment now replacing the Sacred Certitude of the ancestral faith. In between the false binary of “Tradition and Modernity,” the counter-culture movement that Mohassess best represented visually paved the way toward a mode of agential presence in history that was no longer trapped in the fake feud between “Islam and the West.” Thus by visualizing the verbal domain of Signification back to its site and sight of the Sign, the counter-culture of dis-obedience maps out its route of revolt.

Mohassess is the most blatantly political portraitist of the visual, revealer of the evident (otherwise verbalized to anonymity), the signature of the Sign of our revolt, political to the core of his aggressive acculturation of the verbal into the visual, reminding letters they are nothing but shapes, words nothing but signs. His politics is not just a politics of having-been-there or a politics of having-seen-it, but a persistently palpable politics of still-being-there, a politics of still-seeing-it. He is still-there. The so-called “exilic” condition is nothing but a topographic displacement on the Nomanland of not-quite-there. You are neither here nor there. But you are here, and yet you are there. Between here and there, reality evades a finalizing tonality, a narrative totality, a from-here to over-there. Nothing is the Same. Everything is different, the Other. No Hegelian totality—only a Levinasian alterity, though (and there’s the rub) without the necessity of the Levinasian Invisible or Infinite. Time breaks, stories are halting. Accents announce the stranger in the language. In Mohassess’s case, though his demarcations remain native and natal to his birth and breeding, he has been mocking the world he sees and he knows brutally well for now close to five decades, half a tumultuous century. Under his gaze the world he sees dissolves, dis-figures, falls apart, breaks into pieces.

On the sur-Face of those pieces, Mohassess rests his case. In Mohassess, though breathless, we come up for air, come up to the sur-Face, taking everything at the Face value. Down with the Depth, he proclaims in the utter matter-of-factness of his visual sur-Face. Long live the sur-Face! Hermeneutics is Hell. The real is a meaningless picture, full of wonders, signaling life, signifying nothing. The tyranny of the ontological underlines the terror of its totalizing abstraction of the palpable, the particular, collapsing all and the very claim of the Universal. The constitution of our totalizing universal as a people—as Muslims, Iranians, humans—has been through the prose of our metaphysical burdening of the real. As inheritors of a constitutionally verbal culture all we have been able to do is poetically shake and shatter the authority of the word over our destiny. Politically worded, we have poetically revolted. Thus poetically shattered, the culture has always been incubated for a visual sublimation. Visualizing the verbal back to the sign via the poetic shattering of the word, the Iranian counter-culture of anticolonial modernity defied its colonially constituted predicament and mapped out a route of revolt. Revolt, though, not in the political parameters of our inevitable defeats. Revolt in the creative consciousness of our visual defiance of the written. Our fate was written somewhere between the colonially conditioned modernity and the traditions it invented to believe (in) itself. Against the letter of that fate, we have visually re-imagined ourselves. Mohassess is the vision of our evidence.

If Mohassess is not at home at the heart of an empire that projects it on parochialism onto all worldly cultural artifact it exhibits, he has also lost his home in a homeland that has now degenerated into a theocracy and all but destroyed the cosmopolitan culture that once embraced and celebrated Mohassess. What ultimately saves Mohassess and sustains the palpitating aesthetic modernity that once gave birth to it is the historical memory of two dynasties, a theocracy, and now an empire that have all come together and collided in his creative imagination, where the formal destruction of reality is the sure sign of an anticolonial modernity that is yet to map out and conjugate all the signal signs of its Semitics of revolt, against the Semantics of obedience embedded in the very grammar of politics we have inherited, even the ones that teach us how to revolt. The point at which Mohassess breaks the authority of the Signifier and raises a sign of disobedience against it, he and we have had an encounter with history beyond nations and nationalism, colonial dominations or imperial hubris.

The Iranian tenor of that cosmopolitan history is poetic, and Mohassess is the signal mutation of that tenor into pure visual citation. Persian poetry has been instrumental in wedding our memorized poetic voice to the open possibilities of our visual imagination. In this respect, the influence of Mohassess’s mother, who was an accomplished poet and a prominent literary figure, was far more enduring on her son than hitherto imagined. In the course of many printed and public conversations, Shamlu, by far the most eloquent voice articulating our poetic modernity, has repeatedly emphasized that the poetic act is not verbal but visual.24 When Shamlu saw Darroudi’s paintings and wrote his poem on them, something quite critical happened in the contemporary mutation of tyrannical Signifiers (even in their miasmatic poetic mode) back to their far more democratically liberating Signs, through the intermediary of the poetic mediation. It is to that poetic mediation that Mohassess owes his visual angle on the evidence of the real. Mohassess’s distinguishing mark is a figural registration of that wedding of the sight and sound, vision and voice. Through this mixed metaphor, the Iranian creative ego (oscillating between the false agential claims of “Tradition and Modernity”) was no longer the Same—but always an Other, even unto Itself. On the pages of Mohassess, as on the poetic space of Shamlu or Kho’i, the question once again became pertinent as to what it exactly means to be a Person, an Iranian, the possessor of a creative ego, author of an agential autonomy, a voice, a vision. (European) Modernity, colonially constituted, defined one ego as the Same, while the Tradition that this colonial modernity invented (from alternative modernities) defined another ego equally as the Same. Two creative egos: But both the Same, as the Same. Mohassess visualized, against the authority of the verbal, an alterity exterior to these identical creative egos, either colonial or colonized, imperial or vanquished, “Modern or Traditional.”25 External to the ego, this alterity was real, for real.26 Mohassess disturbed, exorcised, cut both ways. Aided by the poetic, its visuality leading an armed uprising against the terror of the text, the reign of the verbal, the tyranny of the textual. It was written. But he showed it unto us.

Mohassess’s signs signate; they do not signify. His pictures point to spaces, domains, fields, of significance, but never hang any meaning on any stable and stabilizing hook. His work is thus “political” in a far more radical and iconoclastic way than just being the nightmare of all sorts of tyrannies, from the Qajars to the Pahlavis to the Islamists and now down to militant Neoconservative imperialists. It is imperative to place his work over the last quarter of a century that he lived in the United States (and not just his post-9/11 work) right next to his work launched against the grain of tyranny under the Qajars, the Pahlavis, and the Islamists. His critic of US imperialism is in effect the logical culmination of his critic of all the mini-tyrannies that have afflicted his homeland. But none of those evident criticisms should detract from the far more radical formal destructions he has launched against a form of tyranny that underlies all else. Mohassess’s work is the nightmare of the verbal legislation of reality into an absolutist grammatological tyranny. Through the intermediary of the poetic, his work is representative of a generation of visual artistry (in his case bordering on figurative sophistry) that led the rambunctious signs out of their incarcerated dungeons and let them loose to dance in the streets and alleys of democratic signation. In that signal act of busting out of the semantic Bastille (Evin, Abu Ghraib, or Guantánamo Bay), his art is the very vision of an alterity that sets the political tyranny of language off balance.

If “the ego cannot engender alterity within itself without encoding the Other,”27 we (the creatures Mohassess has made possible) are the Other. We became a contradiction to our own Selves (always a dialogical product), the instant we were made to be the Other of “the West” (always a fiction, only a fictive force to the extent that colonial site made it possible, as Fanon rightly suggested). It is not accidental, at the European Center of the delusion that was the Enlightenment, that the post-Holocaust Levinas turns to the centrality of the Other and posits it as constitutionally different from the Same. Now look at the cycle of Mohassess’s work he calls “Holocaust.”28 There is an integral consistency between them and the rest of Mohassess’s work. It is not a stretch for an Iranian artist of Mohassess’s generation to identify with the Jewish Holocaust. The condition of coloniality and Holocaust are the same story told from two ends. Levinas’s attention to the naked Face of the Other as “the original site of the sensible”29 is all but inevitable after the visitation upon the catastrophe. It is “the Other in its moral solitude”30 that reminds Levinas of its presence, leading him to insert “Responsibility for the Other, for the naked face of the first individual to come along”31 between the uncertainty of the Da and the facticity of the Sein in the collected (and scarcely managed) anxiety of Dasein. In order to confront the Heideggerian ontic-ontology of Dasein with an ethics of responsibility absent in that nexus, Levinas reads the Biblical “Here I am” (I Samuel, 3:4) as the place where the Infinite enters history while withholding any sign of delivering itself up to vision. In effect, Levinas compensates and reciprocates Heidegger’s ontic being-toward-death by his ethical being-toward-God in order to make the responsibility toward the Other possible. This is a heavy price that Levinas is willing, following Dostoyevsky, to pay. The price is the categorical mutation of all Signs into Signifiers, an absolute precondition to make the metaphysical centrality of the Infinite and the Invisible (otherwise an impossibility) possible. The problem is not only the leap of faith that in the absence of the Face of the Invisible we will have to make in order to make that impossibility possible.32 Certainly the ethic of responsibility toward the Other will make us pause and think twice about the necessity of that leap. The trouble starts when the being-toward-God does not only balance and soothe the being-toward-death and thus introduce the necessary rupture in the Dasein’s inclinations toward self-understanding and thus ontology, but carries with it a theocentricity that impregnates that very checked-and-balanced ontology into a theo-ontology, the very condition of the Metaphysics of Presence on whose site the benevolent Unseen presides as the Transcendental Signified. Both for the Dostoyevsky of The Brothers Karamazov and his active Russification of Christ and for the Levinas of the post-Holocaust despair, it is equally easy to understand as to why the centrality of this ethical intervention into the ontic is crucial. But none of them had to experience or try to understand the imperial logic of European colonialism, or, upon its inverted logic, the metaphysical terror of a ruling theocracy, an Islamic Republic, ushering a whole cosmopolitan culture into the twenty-first century.33 Thus on the colonial site, where we have already paid a heavy price of a much bloodier and bony sort, and where we have produced artists like Mohassess, no other such heavy price of suspending signation on meaningful signs, of incarcerated signs on signification, and all metaphysical signification on a necessary Transcendental Signified (what Muslim theologians used to call Wajib al-Wujud—the “Necessary Being”) is necessary.

Instead of fabricating a Transcendental Signified to hold his universe together, Mohassess goes on a rampage and opts for a massive celebration of signs—a festive, furious, figuratively erotic eruption of unruly signs—and thus to come to terms with Mohassess, he has to be seen as a celebrator of signs, and never as a catalyst of signifiers. Infinitely more important than his varied and compelling contents are thus his forms, his formal destruction of things. He is our Picasso, Miró, and Kandinsky all in one. The world that Mohassess has created is no longer a reflection of reality, for any such reflection, no matter how critical, still remains in the field of the Same. As a post/colonial artist, he has witnessed the horror of not just seeing the Other (as Levinas recommends) but of being the Other. What Mohassess portrays—his figures and figurines—is the kaleidoscopic vision of a reality sui generis. His kaleidoscopic vision—contorted figures and convoluted gestures—is the tabula rasa of our sort of being-in-the-world. He is not exaggerating reality. This is the reality, not just as he sees it, but as it is. He does not distort reality. He takes a photographic picture of its actual traces. The only thing that has not happened in the pictures that Mohassess takes from reality is their forceful legislation into a grammatical order of meaningful messages. He keeps such messages always at bay. He is, as he was afraid of Islamic law throughout his youth, wary of all manners and claims of Transcendental Signified. He has no use for them. He is free of them, as are the pictures he takes of reality. He is our Levinas, and then some, practicing visually what the great European (if he were only a bit more Jewish and less European) philosopher could only preach verbally.

At the European Center of Enlightenment, even when de-centered after the Jewish Holocaust, Levinas posits God as the Absolute Alterity in order to place Him outside the ontological analytic of Dasein even in its Heideggerian destruction of Metaphysics. Levinas believes that although Heidegger has succeeded in reaching for nothingness not through a theoretical destruction of metaphysics but through the radical dwelling on Existence itself, nevertheless he remains ontological with such notions as finitude, being-there, and being-toward-death being “cardinal” in his thought. To break such cardinals and to out-destroy the master of destruction himself, Levinas invites the Divinity in, arranges for a face-to-face encounter with the Other, in the absence of the Face of the Infinite that balances the epistemic with the sacred. The certitude of being-toward-God (á-Dieu) is to check and balance the anxiety of being-toward-death and thus necessitate and implicate an ethical obligation toward the Other. But precisely in this success dwells the danger of re-theologizing an ontology that Heidegger had tried to de-theologize and Levinas himself is trying to disseminate but manages to re-theologize. The catch-22 that results obviously gives a moment of ethical self-reflection to the post-Holocaust Europe. But Levinas remains totally and tragically careless as to the implications of his ethics of responsibility in colonial conditions where the re-invention of theocentricity in precisely similar moments of anxiety has had catastrophic (theocratic) consequences. Not only in the Zionism that Levinas inevitably had to embrace was God put back into politics, and thus philosophy taken out of history, for the same is true of the militant Islamism that Levinas could not but have deplored, and the Christian imperialism with which he found himself (how strange) in alliance.

On the colonial edges of the imbalance we can afford no such carelessness, for there the world at large suffers the consequences of an Islamic Republic, a Jewish State, a Christian Empire, or a Hindu Fundamentalism alike, the instance our worldly cosmopolitanism is forgotten, historicized, museumized, or anthropologized. Mohassess is the visual evidence of that worldly cosmopolitanism, fully thriving at its normative height, always wary of any Transcendental Signified tyrannizing its flamboyant and unruly signs of freedom and/or even anarchy.

What Levinas’s facial encounter with “Sacred History” forgets is that his sacred History is by the accidental fact of his birth and breeding Jewish which ipso facto demarcates the Other’s as Islamic, Christian or a host of other potential and actual sacred histories, in plural. Yes indeed he “can quote Psalm 82 to shake the foundations of ontology with the primordial necessity of justice, or read the inhabitants of Canaan as a comment on the Heideggerian order.”34 But by then a Pandora Box of unfathomable horror has also been opened. If Muslims were to take their sacred History equally seriously, having the Qur’anic verses and the Abrahamic anti-paganism to bear on their epistemic genealogy, how are they to look at their Jewish Other without betraying the very Qur’anic letter of that Sacred History? Why is it that the single human being that Levinas could find to conform to his Talmudic interjection of an ethic of responsibility toward the Other is an Arab Muslim? In his “Politics After,” he celebrates the late President Sadat’s “greatness and importance,” and his visit to Israel as “that exceptional, trans-historical, event that can be witnessed only once in a lifetime.”35 Sadat’s moral courage, or political treason as many Egyptians, including his assassin, and other Arabs and Muslims thought, his ethical responsibility toward his Jewish Other was almost certainly not predicated on his reading of Levinas Totality and Infinity, or on his Talmudic learning, or Biblical knowledge. It was certainly nothing remotely related to his being a pious Muslim and reading his Qur’an carefully and dutifully.

In order to make the naked face of the Other the site of ethical responsibility, Levinas has had to restore a faith in the Face of the Unseen. But that reduction of the evident visible to the Immanent Invisible is only necessary where the face of the Other is so constitutionally alien to the European Civilizational Same. That is not the case, however, on the colonial site of alterity where the face of the Other is the site of immediate visibility. If Levinas could only stop looking at the face of the Jewish victim of the Holocaust, the absolute Other of the Christian Europe, through the eye of the European Same, if he could only look at his own face as the Same of the European Other, he would not have to interject the force of the Invisible in order to invalidate the face of the Other. He, as a Jew, has always been the Other of Europe. But his European eyes could not see that. And thus the necessity of the Biblical Invisible, on the site of whose Invisibility the Christian Europe could tolerate the Jewish Other. As the Civilizational Other of the Metaphysics of Presence that made horrors of the Holocaust possible—and Levinas trembles at that sight to the point of bringing the Hebrew God back in—we (the colonial consequences of European modernity, the creatures Mohassess has seen and visualized) are in no need of such a re-entry. They can stay in the heavens, where they belong. “Behel kin asman-e pak,” says Mehdi Akhavan Sales in a magnificent poem:

[Let the pure heavens

And others like him, for sinners like me

Could never figure out

Who the father of these pure prophets is

Or what is their use.]

This is no theological blasphemy. This is a philosophical proposition—for here on earth, the wretched of the earth are the Other. Our ego on the colonial site has never been the Same, except as colonial subjects or its mirror image, “Traditional Believers.” There thus remains very little difference between Levinas and his embracing of Zionism and the chief ideologues of militant Islamism and their calling for a Jihad against the “Crusaders.” For both the Face of the Unseen is to be located on the face of the Other. But the Muslim Other is the Same. It is Itself. He (and it is always a “he”) has no tolerance for another Other.

Look at Mohassess now. The cycle he calls “Holocaust”: The broken man, the scooped up broken visage of a puppet as puppeteer that is the man. Broken, fallen, the defeat of itself, the collapsed version of an otherwise erect puppeteer who can no longer act or direct, be or let be, the broken version of itself, holding the command of its promised puppeteering in hand, yet broken. What image of Man is this? Who and what is the Same, and what the Other? The seated defeat of a broken promise of a would be man, a puppeteer of a man who could have and might have and even should have been a man: The seated memory of an erect attendance; the faded memory of a balanced and erect appearance, presence, power, assertion; the dream, the nightmare of the puppeteer; the faded memory of the hand, remembering, as it is forgetting, itself. The puppeteer. Notice the absence of the face. The prominence of the hunchback, the broken back prominent, pointed, the summit of a defeat. The man attending upon himself; unto himself. The puppet and the puppeteer in the memory of the Same and the Other. The Same and the Other. The defeat of the man in his own hand. His collapse.

To see that collapse you need no ethics, no metaphysics. Now read Levinas: face-to-face. Thinking himself in conversation with what he called “Western philosophy” on a post-Holocaust moment, Levinas had to call the “positive movement, which takes itself beyond the disdain or disregard of the other … metaphysics or ethics.”36 This is myopic vision. Levinas never had to escape the horrors of an Islamic Republic and his reading of the Holocaust had blurred his vision of Zionism and blinded him to the sufferings of the Palestinians. Otherwise that metaphysics or ethics is entirely superfluous and redundant from the side of the Other Itself. Levinas was too much of a European to be a Jew, too much blinded by the horror of Holocaust to see the terror that Zionism visited upon the Palestinians. He could only imagine and posit the Other in order to bring God back into philosophy on the naked face of the Other. But we are not. If “for Levinas … desire is the respect and knowledge of the other as other, the ethico-metaphysical moment whose transgression consciousness must forbid itself,”37 then the moral agency, which is thus required, needs an entirely different site than the very idea of Europe.

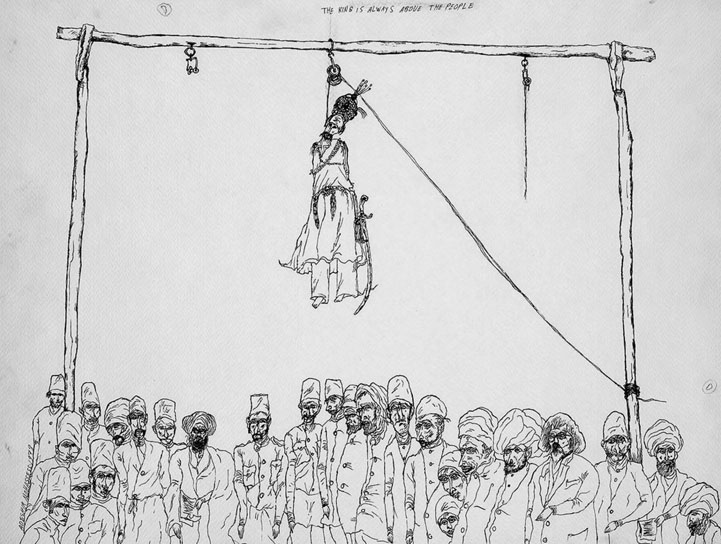

On an alternative site, in a critical re-casting of moral agency, Mohassess was among a generation of visual artists who gave birth to a people as an Other that was Other to no Hegelian ego, and could believe in no Same. Consider the satirical brutality of Mohassess’s military mockery. The military mocked: Generals in a row, across the historical line, beyond culture and uniform, all in a formal row, proclaiming themselves, announcing the belligerent, the bellicose, ready to fight. And yet the mockery of it all. Men in arms, uniforms and medals, facial expressions with a minimalist precision of their own parodies. Men as their own parodies. Persian parodies. Men in arms. Standing erect. Looking ahead. Marching to the eternity of an absurdity. Mohassess is the death sentence of a culture against itself, the teasing out of the worst, the staging of it, putting it on a platform for all to see. Mohassess is the exorcising of a culture, of its most debilitating fears come true. He teases the real beyond itself, pushes its edges to the surreality of its demand upon our credulity. Would you believe this? I don’t believe this. I do.

Come and watch now. Mohassess: From the middle of the twentieth to the beginning of the twenty-first century. The diagnostician of cultures in fear of themselves—monarchical, Islamist, Imperialist—visualizing the living daylight out of their verbality, tyranny, terror. Come and take a good look now. Mohassess: The Same as the Other; the Face of the Other in Itself; the Face exposed, in fear. The Face naked, neutral, fearful, a mere memory of its own nobility. The Face as monstrous—more a mirror than a face, the crocked timber of its exposure, the immorality of its violent defenselessness. Mohassess’s faces are naked, exposed, silent. These faces are in defiance of the voice. They do not, will not, speak. They are neither the beginning nor the end of discourse. They are its denial, refusal, condemnation. They are the suspension of the langue, bracketing of the parole, visual utterances suspended onto themselves. The Other of these faces, and these faces as the Other, is in their utter, irreducible, inaudible, visuality. The responsibility they announce is not just in the language of the metaphysics they denounce, ideological and otherwise. Nor is it ethical, sacred or secular. It is a responsibility in the face of the full aggression of the evident—meaningless, hopeless, pointless, faceless—that attenuates these faces. They revel in their devilish defiance of the order. And yet they are not the Other. They are the Same: Humanity at large.

*First published in Ardeshir Mohassess: Art and Satire in Iran, 2008.

1For the two most recent publications on Ardeshir Mohassess see Ardeshir Mohassess, Closed Circuit History (Washington, DC: Mage Publications, 1989), and Ardeshir Mohassess, Life in Iran: The Library of Congress Drawings (Washington, DC: Mage Publications, 1993).

2Giorgio Agamben, Homo sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Translated by Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998/1995): 18.

3There is a wonderful interview with Sorur Mahkameh Mohassess in the special issue of Simorgh (Numbers 75–76 [1377/1998]) on Ardeshir Mohassess, which include her reminisces about the most gifted poet of her time Parvin E’tesami.

4For further details of this period, see the chapter on the Constitutional Revolution in the author’s Iran: A People Interrupted (New York: The New Press, 2007).

5These biographical data are available from a variety of sources. I take them from a special issue of Simorgh, Numbers 75–76 (1377/1998).

6Various collections of Ardeshir Mohassess’s work have appeared in Iran and other countries. Chief among them early in his career were Cactus, Ed. Sirus Tahbaz, Daftar-ha-ye Zamaneh (Tehran: 1971); Ardeshir and his Masks (Tehran: Tus Publications, 1971); Instances, Edited by Kambiz Farrokhi (Netherlands, 1973); Ceremonies, with an Introduction by Aydin Aghdashloo (Tehran, 1973); Current Events, with an Introduction by Ahmad Shamlu (Tehran, 1973); Identity Card (Tehran: Tahuri Publications, 1973); Ardeshir and Stormy Weather, with an Introduction by Ali Asghar Hajj Seyyed Javadi (Tehran, 1973); Free Sketched, with an Introduction by Reza Pudat (Tehran: Nemuneh, 1973); and many others.

7As an undergraduate student I attended the opening of this exhibition in a gallery in downtown Tehran. That was the first occasion I actually met Mohassess and purchased a signed copy of his Current Events. Years later, soon after the 1979 revolution, when I met Ahmad Shamlu in a dinner party in New Jersey, he said he had lost interest in Mohassess’s work, that he thought Mohassess kept repeating himself. He was wrong.

8See Iran Darroudi, Athar-e Naqqashi (Tehran: Offset Press, 1352/1973).

9To be sure, we have had such poet/painters as Sohrab Sepehri and Manouchehr Yekta’i. But they have, by and large, kept their poetic and painting practices separate.

10See Darroudi 1973: the first few pages of the book on the Persian side. No pagination. There is an English translation of this poem by an anonymous translator on the English and French side of this book. I have preferred to do my own translation of the original.

11Years later, and while residing in the United States in the immediate aftermath of the 1979 revolution, Shamlu launched a similar iconoclastic attack against the Iranian national poet Ferdowsi and against classical Persian music. Needless to say, these attacks deeply angered and alienated Iranian nationalists of all sorts against him.

12I have extensively covered these oscillations between the sign and the signifier in my essay “In the Absence of the Face,” Social Research, Volume 67, Number 1, Spring 2000: 127–185.

13Ahmad Shamlu in fact has a similar conception of Persian carpet designs. He once said because we were juridically forbidden to compose and perform music publicly, we sublated our musical compositions into winding floral patterns in our carpet designs. It is a beautiful idea, but it obviously disregards the sinuous melodic designs of classical Persian music even despite its doctrinal inhibition, which points back to yet another uproar that Shamlu caused when he categorically denounced classical Persian music as stagnant and unresponsive to massive social and cultural changes over the last two hundred years.

14Esma’il Kho’i, Shenakht-nameh-ye Ardeshir-e Mohassess (“An Introduction to Ardeshir Mohassess”) (Tehran: Amir Kabir, 1973): 11.

15Ibid., 13. Emphasis mine.

16Ibid., 14.

17Ibid., 28.

18Ibid., 35.

19Ibid., 39. Emphasis mine.

20Ibid., 41.

21Ibid., 75.

22Again, I have unpacked these differences in more detail in my essay “In the Absence of the Face”.

23Here note in particular Mohassess’s repeated assertions in his interview with Kho’i that he feared and trembled in his high school courses he had to take in Islamic law and jurisprudence. “I had no idea what Islamic Jurisprudence was all about. Still I cannot make head from tail of it” (Kho’i 1973: 47). Because of the identification of Islamic Law with Arabic language and the scholastic way it was taught in high schools, Mohassess’s anxiety is extended into Arabic language too. “I hated Chemistry, but I hated Arabic even more” (48). Here you notice his visual approximation of inexplicable chemical formulae to incomprehensive Arabic phrases—the inaudible verbal assimilated back to incomprehensive visual, both feared in their physical evidence, both mocked in their being “Greek to me.” This predicament continues well into his college years: “Unfortunately, Islamic Jurisprudence (initially [in the form of our courses in] Islamic Law) and Arabic language have been chasing me since my early school years. I had no idea what in the world did these two subjects wanted from my life. In the first two years of college we still had to take these courses. If I wanted to pursue a degree in law I would have had to take yet another two years of these two subjects. It was to get rid of them that I opted to go to political science. So contrary to my first two years at college in which I had a horrible time, in the last two years I had a really good time. Finally I could breathe comfortably” (51).

24For a representative statement of Shamlu on poetry see his “Sha’eri” (“Poeticity”), in Javad Mojabi (Ed.), Shenakht-nameh-ye Shamlu (Tehran: Ketabsara, 1377/1998): 391–402.

25What absolute calamity (moral, normative, and intellectual) has these two terms and their binary opposition in modern Iranian history created and sustained is impossible to exaggerate. For my critique of this binary and the way out of their cul-de-sac see the Postscript to my Iran: A People Interrupted.

26This I offer to be read against Derrida’s reading of Levinas: “The ego is the same. The alterity or negativity interior to the ego, the interior difference, is but an appearance: an illusion, a play of the Same ….” (Jacques Derrida, Writing and Difference. Translated, with an Introduction and Additional Notes, by Alan Bass. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1978): 93.

27Derrida, Writing and Difference: 94.

28When the inanity of the “cartoons” that some officials of the Islamic Republic had commissioned and exhibited on the Holocaust emerged in 2007 (in retaliation against the Danish Cartoon Row of 2006), not a single soul, not a solitary voice, uttered the fact that the single most important Iranian cartoonist, Mohassess, living in the United States (and in New York for that matter) for over a quarter of a century, had already done a magnificent body of work on the horrors of the Jewish Holocaust and then linked them to a more universal condemnation of vicious tyrannies the world over. Why this silence, or omission, or negligence, or ignorance? The answer might be sought in the same pathology that categorically excluded a single representative work of Mohassess from a show that MoMA (Museum of Modern Art) in New York had organized in the very same year of 2006, titled “Without Boundary: Seventeen Ways of Looking.” Between nonsense and delusional pathology there indeed might be a very thin line. But the public perception of reality is also shaped on the very same line.

29Emmanuel Levinas, “Ethics as First Philosophy,” in Seán Hand (Edited), The Levinas Reader. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989: 82.

30Ibid., 83.

31Ibid., 83.

32For which desire see “Desire of the Invisible” in Emmanuel Levinas, Totality and Infinity (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1969): 33; and then compare with my “In the Absence of the face”.

33Were he not committed to Zionism, Levinas could have seen the Jewish State in the same light as I see the Islamic Republic. But he did not. He remained committed to Zionism, and thus to the Jewish State. I categorically and unconditionally oppose Islamism, and thus the Islamic Republic. Levinas could never see the broken face of a Palestinian as the site of his ethic of responsibility. His articulated philosophy was far more emancipatory and progressive than was his practiced politics.

34Seán Hand in Levinas, “Ethics as First Philosophy,”: 7.

35Ibid., 282.

36Levinas, “Ethics as First Philosophy”: 92.

37Derrida, Writing and Difference: 92.