The 1970s were a disturbing transitional period for many Americans. Decline of social institutions that formerly solidified and signified the American identity contributed to much of this turmoil. Politically, culturally, and economically the country was going through changes that were affecting it in adverse ways. Vietnam veterans were coming home from the war disillusioned and broken, the country was realizing that its political leaders were corrupt, and inflation had reached new heights. It was during these chaotic times that Craig Gilbert's An American Family (1973) aired on PBS. This series, the first of its kind, would later inspire the reality TV phenomenon of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. An American Family, consisting of twelve one-hour episodes, featured an ostensibly “average” upper-middle-class family and presented many contemporary concerns to a broad viewing public. Those involved in the filming process understood its unique concept of following ordinary people and documenting their lives. In an effort to save a sinking station, James Day, the president of NET (PBS's New York affiliate) opted to create a show that would “address the vast changes that were occurring in American society, ‘particularly with young people—their attitudes towards drugs, towards sex, towards religion’ “(quoted in Ruoff 12). In the spirit of cinema verité1 and its American counterpart, direct cinema,2 Craig Gilbert proposed a series that would look at the institutions of marriage and family by following a “traditional” American family. Rather than adhering to the mandates set forward by cinema verité and direct cinema, however, Gilbert manipulated everything from casting to editing to publicity to assert that family and marriage were dying institutions and that the American dream was in decay.

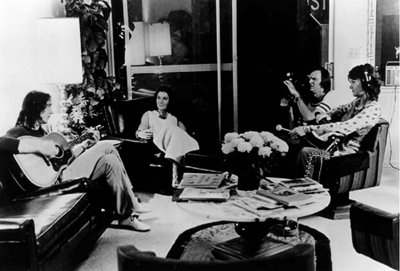

Filming An American Family (PBS) in 1973. From left: Grant Loud, Pat Loud, Alan Raymond, Susan Raymond. Courtesy of PBS/PhotoFest.

Craig Gilbert had a fixed thesis in mind as he began a search for “the quintessential American family.” He drew inspiration from Allan King's A Married Couple (1969), Charles Reich's The Greening of America, Theodore Roszak's The Making of a Counter Culture (1968), and Ross Macdonald's The Underground Man—all of which attacked bourgeois institutions such as marriage, capitalism, and the American dream. His choice of the William C. Loud family (Bill, Pat, and their children, Lance, Kevin, Grant, Delilah, and Michele) allowed him to explore problems that festered below the surface of perfect facades.

The first book to influence the making of An American Family was Ross Macdonald's The Underground Man (1971). According to Jeffrey Ruoff, the novel “perfectly described” the type of family that Gilbert was looking for (17). Macdonald demonstrated how wealth alone could not provide happiness or balance to individuals with questionable morality. The Loud family of Santa Barbara, California, fit this mold. Its members were clean-cut, affluent, and attractive, yet the tension that was palpable between them from the first scene indicated to the audience that something was not right. The second influential book was Charles Reich's best seller The Greening of America (1970). This text analyzed the cultural revolution that overtook America in the 1960s and 1970s. Reich's book looked at the demise of the family and the disintegration of the dream, celebrating—as An American Family does not—the rise of a new consciousness of communal peace and love. Personal experience with a crumbling marriage and divorce further influenced Gilbert's interest in the project. When Curt Davis, Gilbert's supervisor, asked him to write up a proposal for a show that he had always wanted to do, “Gilbert thought about it during the weekend in which he ‘drank a lot and wallowed in self pity’ over his failed marriage. Somewhere, buried in the troubling question of why men and women have such a tough time maintaining relationships, was the germ of an idea for a show. He grabbed a pencil and began making notes. The result was the outline for An American Family” (Landrum and Carmichael 67).

Susan Lester, associate producer for the project, was also aware of the representational requirements. She knew that they were looking for “a family that sells Cracker Jacks. The kind of family you see on a television commercial, in a pretty house that has the best of what this country has to offer materially…. Material success was as important in what we were trying to say because we were trying to play around with the American dream” (Ruoff 17). Notes for the series were finalized after the Loud family had been settled on, which proves the importance the producer placed on locating the unscripted cast. The Loud family fit the filmmakers’ agendas so well that, in spite of a concept that originally planned to concentrate on four families, the Louds became the only social unit central to the reality series.

The William C. Loud family met all the series creators’ requirements: they belonged to the upper middle class and lived in a luxurious ranch-style house; with four cars, three dogs, a pool, and the financial ability to take expensive vacations, they seemed to represent the American Dream. The family's perfect facade, however, hid many underlying problems. Bill and Pat Loud's marriage had steadily deteriorated over the years, so much so that Gilbert had the perfect opportunity to explore the troubled relationship between a man and a woman who typified this trend. The family could also perfectly illustrate the issues Charles Reich discussed in his book—the materialism of the old generation and the drug culture of the new generation, the decaying work ethic of the former and the unrepressed pleasure principle of the latter.

The traditional nuclear family in the United States (at least as depicted in the media) usually consists of a loving mother and father and perfect children. The Louds subverted this image of nuclear togetherness in every sense. Bill and Pat's divorce demonstrated that they were far from loving. Their differences and Bill's infidelity presented a more realistic portrayal, and the series played on their tension. When Bill and Pat were together, there was usually distance between them. When they talked, it was usually small talk, inconsequential. In the event that they did discuss their children, two completely different parenting styles emerged. An example of this estrangement appeared in episode 6, when Pat's comments about the children are countered with Bill's advice, “Life's too short to worry about all that jazz.” It became clear throughout the course of the series that rather than simply studying the Louds, Gilbert wished to comment on them. The episodes presented Bill as a nonresponsive father. He continually told Pat that she should not worry about the children and that they should try to get them out of the house as soon as possible. Bill wanted his sons to follow his example, and he completely ignored their desire to find their own roles in life. Pat, on the other hand, wanted her children to be happy, claiming that she did not care what they did with their lives as long as they were content. Her behavior and apparent concern for the feelings of her kids had the added bonus of casting her in the role of the doting mother and the “star” of the series.

There were multiple reasons for the creative decision to give Pat Loud preference over her husband, but the most important seemed to be what each individual represented. During the late 1960s a counterculture began to emerge. This generation, notorious for rebelling against mainstream society, tried to illustrate how old ways of viewing relationships and institutions were no longer tenable. Out of this turmoil came Charles Reich's extremely popular study, The Greening of America, which became a driving force behind Gilbert's vision. An American Family capitalized on Reich's labeling of the different consciousnesses of members of society. A type II consciousness (Bill Loud) was often subject to ridicule. According to Reich, these individuals “are inclined to think of work, injustice and war, and of the bitter frustrations of life, as the human condition” (quoted in Landrum and Carmichael 68). Gilbert and Reich believed this consciousness was antithetical to 1970s sensibilities, and the individuals who embodied these characteristics should become figures with whom new consciousnesses struggled. Pat Loud differed from her husband. She bridged the gap between consciousness II and the next stage. Her children, as the younger, more rebellious generation, embodied Reich's consciousness III. They were interested in individuality and revolting against tradition. According to Reich: “The foundation of Consciousness III is liberation. It comes into being the moment the individual frees himself from automatic acceptance of the imperatives of society and the false consciousness which society imposes…. The meaning of liberation is that the individual is free to build his own philosophy and values, his own life-style, and his own culture from a new beginning” (225).

Because their values differed so drastically from Bill's, the children were in need of a mediator. In this role, Pat understood her children and tried to help her husband strengthen his relationships with them. The problem arose when Bill refused to change his ways of thinking. He remained distant and did not appear to care about the lives of his children. Bill's concern manifested itself only in his desire to help the boys find jobs that would make them self-supporting. Pat's acceptance of the children ensured her popularity among her offspring—as well as among the viewers. She very rarely tried to enforce rules, and she seemed to enjoy and encourage acts of rebellion. The series advanced the notion that, because Pat loved her children, she was able to do things as diverse as joining Lance at an avant-garde musical about transvestites in episode 2 or help Delilah with her costume for a dance recital in episode 3. As a consciousness II, Bill Loud never could perform these types of parenting feats.

The Loud children were rebellious teenagers who listened to rock music and used drugs and alcohol. Lance Loud, the oldest son, was a homosexual who apparently lived by taking handouts from others. An American Family attributed Lance's “outrageous” behavior to a deeper problem. In episode 8, Pat explains that she believes Lance would not have so many problems if “he had felt like his daddy loved him.” Perhaps to explore a timely theme, the cameras focused on his struggles. Lance's decision to come out as a homosexual on national television, while extremely brave, was not all it appeared. According to Lance, though he had known he was gay for some time, he did not make a conscious decision to play up this aspect of himself. In a reunion episode taped ten years after the series aired on television, an older, more mature Lance explains that he thought his behavior was “extremely avant-garde.” He discusses the idea that the promotional material outing him as a homosexual placed him in a very awkward role. For Lance, and the other members of the family, the exploitation of aspects of personalities and situations was extremely difficult. The Louds—like all families—had their quirks and foibles, but ordinary families lack a PBS film crew following and recording their every move.

Bill believed that his sons should want to find work to make money and start their own self-sufficient lives, but Grant Loud preferred to focus his time on his music rather than get a blue-collar job. Bill tried to instill a work ethic in his sons, but neither Grant nor Lance seemed to want to follow his father's example. In episode 7, Bill and Pat try to discuss employment with Grant, but he rebukes them. Grant is the stereotypical spoiled child, receiving everything he wants from his parents. When Bill and Pat force Grant to get a job with the “concrete king of California,” he parties more than he works. As the first television series of its kind, An American Family aired footage of Grant Loud smoking what appeared to be marijuana and drinking copious amounts of alcohol. His behavior seemed to usher in the notion of the “Me Generation.” Interestingly, Grant did not realize that his own behavior mirrored his father's. Even though Bill provided ample material possessions for his family, he did not seem to understand that his children and wife needed emotional support. Unlike Lance, Grant did not appear distressed by his father's detachment. In fact, he savored Bill's absence because it meant he could do what he wanted without reprimands.

Throughout the series, Gilbert returned to his thesis that the American family was broken, even when he filmed seemingly innocent conversations. In episode 7, one innocuous phone call between Bill and Pat's elder daughter, Delilah, and her boyfriend, Brad, becomes a commentary on the institution of marriage. She says, “My dad came home. Oh God, so embarrassing … they are arguing about whether you should put the cheese in the refrigerator or not…. I was so embarrassed. And then Nancy called me and her parents were fighting too.” As she remarks that she cannot bear to be in the position her parents are in, the editing cuts to a shot of Bill and Pat in the kitchen. Bill sits at the table while Pat cleans up after a meal. There is a tense silence between them, and they clearly have nothing meaningful to say to each other; the lack of conversation is evidence of the sterility of their marriage. Although Pat says it in the next episode, it is clear that they “just [didn't] have any rapport at all anymore.” Delilah's commentary about her friend's parents furthers the notion that the Louds are typical of many American families. To Pat and Bill, their home is not a comforting haven; it is a place of discontent and disharmony that they ultimately seek to flee. Furthermore, Delilah's schoolgirl confession of love for her boyfriend glaringly contrasts with the weary strain and futility of her parents’ marriage. Gilbert went for the jugular by setting her seemingly sweet first teenage relationship against the crushing inevitability of the end of love, thus suggesting an unavoidable cycle of bitter disappointment.

Yet another instance of presenting the Louds as representative of all American families came with Bill and Pat's attendance at a cocktail party. In this scene Ross Macdonald's influence on Gilbert's thesis is revealed as characters seemingly stripped from Toulouse-Lautrec paintings swarm about in a daze of debauchery. As Ruoff observes, the claustrophobic cocktail party, “the careless party chatter, the sunglasses, the liquor, the leathered faces, the Hawaiian shirts, and the suggestion of extramarital affairs all combine to create an atmosphere of upper-middle-class suburban decadence, California style” (72). Bill asks about a woman's plans, and when a perturbed Pat replies, “Well, for the record, she is just passing through,” Bill chuckles anxiously, suggesting his past philandering. As the woman he is plying with liquor and flirting with chortles that he is “going through a very dangerous age,” the camera continues to focus on Pat's studied effort to avoid observing Bill and his companions. Yet her tautness clearly demonstrates that she is well aware of her husband's wandering eye.

In addition to the uncomfortable cocktail party, Bill's own commentary on his unhappiness makes it clear that the series’ thesis on the demise of the institution of marriage may not be inaccurate. Bill is quick to point out his dissatisfactions with his wife and family. In episode 12 he says that he objects to the family being a “twenty-four-hour deal.” The belief that the family needs a man's total devotion and time was prevalent, according to him, because “somebody has sold society a bad bill of goods.” Barbara Ehrenreich writes, “According to writer William Iversen, husbands were self-sacrificing romantics, toiling ceaselessly to provide their families with bread, bacon, clothes, furniture, cars, appliances, entertainment, vacations and country-club memberships” (48). Bill feels that he has played the part of this unselfish, noble, and deluded romantic far too long and it is time for him to break out of that stultifying existence. The preceding scene shows Pat sitting down to have a discussion with her children and laying down some practical rules that they will have to follow after the divorce. Later she tries to rationalize with a less-than-enthusiastic Lance about his future hopes and vague aspirations. The editing of these scenes shows that it is Pat alone who is willing to take the role of interested facilitator in family affairs. Bill wishes to be free, enjoying vacations without familial obligations, leaving all the responsibility to his wife. Pat rightly says to her sister-in-law in episode 8, “He doesn't wanna be home very much.” Bill even fails to understand the sacredness of marriage; he refuses to accept, let alone appreciate, the fact that marriage is a joint venture requiring an equal investment from both parties. Indeed, as Pat tells her brother and sister-in-law, Bill truly believes that his family should be a vital but small part of his life. He desires the role of occasional parent, a man simultaneously adored and left alone. Bill is bent on being a mere consumer and beneficiary of his family's goodness rather than an active worker in its more mundane but necessary business. Pat sums up their relationship when she observes, “When he says jump, you'd better believe we all stand up in a row and jump.” If Bill is the figurehead and CEO of Loud Incorporated, then Pat represents the underappreciated manager whose efforts keep him free for vacations and chummy cocktails with female admirers.

In conjunction with the presentation of individual family members and their personal issues, the series employed effective editing to demonstrate that the institution of marriage was no longer a part of the American dream. From the opening sequence of the series, the music is upbeat at first as faces of the family members come onto the screen. The title evokes elements of the popular late 1960s-early 1970s television series The Brady Bunch; however, by the end of the sequence it is clear that the Louds are nothing like the Bradys. In the opening sequence of An American Family, the different members of the Loud family are separated from each other by a freeze frame that isolates each member in his or her own little square, much like the opening montage of the Brady Bunch. These squares soon swoop into place and fit together like so many puzzle pieces. The music becomes increasingly frenetic as the words An American Family appear on the screen. Finally, the word Family cracks, suggesting the institutional breakdown. This opening montage forewarns of the problems the Louds face.

If the title graphics do not sufficiently present the situation of the declining family, the series flashes forward to the last day of filming. A voiceover narration declares, “This New Year will be unlike any other that has been celebrated at 35 Wooddale Lane. For the first time, the family will not be spending it together. Pat Loud and her husband, Bill, separated four months ago, after twenty years of marriage.” At the New Year's Eve celebration, a lonely Pat reads a book, watches her children dance, embraces her youngest child, and finally hugs a dog as the New Year needles its way into her miserable night. The film cuts to a shot of Bill Loud drolly dancing with his new girlfriend. The decision to begin this way heightened the dramatic effect of the reality series and further reinforced Gilbert's thesis about a dying American institution. At the outset he wanted to tantalize viewers with a chance to scrutinize a family scandal. The move was reminiscent of those found in any number of popular soap operas and prescient of those of more recent reality TV series. Gilbert, like fiction directors, teased the audience into tuning in for the next episode and begged for value judgments to occur in the interim.

According to the American dream, a man must, by dint of hard work, pull himself up by the bootstraps to acquire worldly possessions and position. Indeed, that was a work ethic that Bill Loud aspired to in every outward way. It was obvious he believed he was a sterling example of what can be achieved by tireless labor and clever dealings. According to Charles Reich, such men believe that “the individual should do his best to fit himself into a function that is needed by society, subordinating himself to the requirements of the occupation or institution that he has chosen. He feels it is a duty, and is willing to make ‘sacrifices’ for it” (72). Bill, illustrating Reich's argument, was constantly traveling to get more business, even though while traveling he did not have the comforts of home. He was a businessman to the core, and he considered such sacrifices necessary, since, as he tells his friend in episode 12, if his family expects to live the American dream he has to remain on the road. That is not to say that he feels himself an ennobled martyr for money; rather, he feels that his sacrifices, justified by his success, define him as a man.

A scene from An American Family (PBS, 1973). Pat Loud is at center. Courtesy of PBS/PhotoFest.

Bill had financial success, but he did not have some of the ethical values that were inherent in the dream. According to Reich, “The American dream was not, at least at the beginning, a rags-to-riches type of narrow materialism. At its most exalted … it was a spiritual and humanistic vision of man's possibilities” (22). Bill completely failed to understand the greater potentialities; his version was limited to monetary success, and those admirable qualities that had made him a successful businessman were missing from his personal life. John G. Cawelti has pointed out that any “thought about the self-made man placed its major emphasis on the individual's getting ahead; its definition of success was largely economic” (5). Bill could well agree with Cawelti's definition of a successful self-made man. He was devoted to his job and to financial success, but not to his family, in effect resembling some flashier, more business-savvy, sexually predatory version of Arthur Miller's Willy Loman. He was a responsible and resourceful entrepreneur, but he shirked responsibilities at home, and though Lance mentions it jokingly in episode 11, he had indeed taken “the business of being a dad too lightly.” In 1955 Manfred Kuhn wrote about eleven reasons men do not marry, and “unwillingness to take responsibility” is one of them (Ehrenreich 20). Because Bill had married but often wanted to live the unattached life of an irresponsible bachelor, he frequently felt his family was a burden. The most vital component of the American dream is the family, yet Bill did not have any inkling of that fact.

Bill's limited idea of success caused him to neglect elements of his life. He placed objects and wealth above family and marriage, and it was this characteristic that drew Gilbert's attention. Reich explained how financial excess had become an aim for many individuals when he wrote, “‘The money’ is now being spent for consumer goods. It is being spent on all of the things, large and small, that make up the affluent American way of life—automobiles, appliances, vacations, highways, food and clothing. All of these things have reached beyond any standard of necessity to higher and higher standards of luxury” (164). For the Loud family and many like them, wealth became problematic. Bill worked to provide for his family, but the one thing the family needed was denied. Rather than forming bonds with his children and wife, Bill was aloof and at times disgruntled. He was an example of the dangers of striving for the American dream. On the surface his family appeared to have achieved a type of perfection, but the declining marriage and the breakup of the family provided a counterpoint to that outward positive appearance.

Perhaps the most overt manipulation of material came during the postproduction phase of the project. The press kit distributed with An American Family clearly demonstrated the director's underlying message of the death of the American dream and the destruction of the family. In much of the promotional materials the family was portrayed as less than ideal. In the reunion episode Pat Loud explains her frustration when she discusses the idea that her family was seen as degenerate, broken, and almost monstrous. She explains how WNET described events from the series and individual personalities and then asked the question, “Would you like to live next door to this family?” For Pat, as well as the other Louds, the promotional materials were extremely disheartening. The series gave them their fifteen minutes of fame, but they had to deal with the backlash from having their lives nationally televised. Even more discouraging than the promotional material was the public reaction. Most media and critics attacked the Louds themselves rather than the series. In one excerpt from the reunion episode, the distinguished anthropologist Margaret Mead argues with a group of critics who are insisting on criticizing the family without actually praising the new genre—reality documentary—Gilbert had invented. Mead insists on looking at the series as a new art form, but it seems that not many were able to do so. Separating the art form of reality TV from the personalities of its stars was nearly impossible. Perhaps examining the controversy surrounding both the Louds and the series could help explain the mid- to late-1990s reality TV boom. Looking at the contributions An American Family made to shows such as The Real World helps situate recent reality TV in the same genre as Gilbert's work. In this sense, Gilbert's legacy of thesis-driven documentary was the progenitor of today's most popular reality TV shows.

Audiences who neglected An American Family’s 1973 debut erroneously label MTV's Real World (1992) as the first reality television show. By comparing the two series, it is easy to see Craig Gilbert's influence. Though the idea of a thesis-driven documentary is nothing new, Gilbert's use of the form for television audiences has become a platform from which reality TV can dive into the public consciousness. The first season of The Real World, while garnering praise for its originality, did not do well in the ratings. Its producers, Mary-Ellis Bunim and Jonathan Murray, looked to the PBS series as a source of inspiration. The problem with the first season of The Real World lay in the fact that there was more documentary than drama. The producers did not follow Gilbert's example of building on an inherent thesis. Episodes that included the possibility of either romance or serious conflict were popular. Late into the first season, the producers realized that the viewing public wanted drama, so the next cast was more provocative; as the series progressed, it began showcasing more highly controversial individuals and issues. AIDS activism, gay rights, abortion, plastic surgery, physical abuse, politics, and even Lyme disease all found their forum on MTV. The Real World has gradually evolved into a series concerned with sex. Perhaps this change was inevitable, or perhaps the series creators, like Craig Gilbert, realized that drama is more effective than documentary when it comes to attracting the viewing public. The first season of The Real World tackled contemporary issues such as race, gender, and class, but recent seasons seem to take their cues from the more traditional dramatic soap opera form. Though these types of reality TV shows have their own niche in the entertainment industry, their bases in documentary or even thesis-driven documentary (a la An American Family) is almost nonexistent at this point. Furthermore, looking at new reality TV helps place An American Family’s own editorial and directorial decisions in perspective. With the PBS series Gilbert wanted to explore serious issues of the 1960s and 1970s, the kinds of problems identified by legitimate social observers. In contrast, contemporary reality TV has taken the ability to manipulate too far. In an industry where selling the series is of the utmost importance, reality TV must go to extremes to ensure that the shows are not pulled from the lineup before being aired. This climate of urgency encourages an industry focused on ratings and money rather than directorial integrity, originality, or insight. A series such as An American Family or the early years of The Real World would never survive more than one season in today's ratings-based climate.

Perhaps today's reality TV is the final, decadent stop for the genre. Shock and provocativeness are now the keys to success, and a series like An American Family or The Real World needed to incorporate elements of the fictional in order to continue. Gilbert understood that some manipulation is necessary. He recognized very early on that documentary television must also entertain. Landrum and Carmichael attest to as much when they quote Craig Gilbert as saying: “I feel very strongly that the television documentary, if it is to have any future, it must go in this direction. It must be in a series form—repetition and involvement with characters is what holds viewers—and it must be concerned with the events in the daily lives of ordinary citizens” (66).

Interestingly, Gilbert, with his own manipulations, seems to have opened the door for a modern cinema form that violates all the rules of the documentary. His insistence on illustrating the problems with the American dream and the institution of the family ensures that An American Family is more a social commentary than a study. Gilbert created his own meaning out of the material available, essentially setting the stage for today's reality TV producers. In an article Gilbert admits: “Yes, I am guilty. I had a point of view…. No, I did not think men and women were blissfully happy; no, I did not think relationships, by and large, were mature, mutually satisfying, and productive; no, I did not think family life was the endless round of happy mindlessness pictured in television commercials” (“Reflections II” 290).

Gilbert's thesis concerning the nation's basic social building blocks, then, found ample exploration in An American Family. It is undeniable that the series analyzed a number of social and cultural issues that were troubling Americans during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Rather than adhering to the mandates of cinema verité and direct cinema, An American Family chose to use the material available to tell the story of the dying American dream as documented by the disintegration of the William C. Loud family, and, in doing so, the series ushered in a new genre of television with a study of historic value.

1. New inventions in filmmaking ushered in new ways of looking at the documentary form. Directors began experimenting with the idea that filmmakers could speak truth with the images they film. Going back to the Russian idea of “Kino Pravda” (film truth), the Frenchman Jean Rouch in 1959 coined the phrase cinema verite. Like Dziga Vertov before him, Rouch believed that a director could use the camera as an eye for seeing real life. Rouch first applied cinema verité principles to Chronicles of Summer (1961), in which he let the interviewees and their opinions speak for themselves (Ellis 221). Rouch's idea of film truth is similar to a concept central to anthropological studies. To present an accurate portrait of a subject's life, time, and culture, the camera should essentially observe and record without overtly interfering. If done correctly, cinema verité becomes a tool for understanding, not a tool for promoting agendas.

2. Direct cinema, the American version of cinema verité, seems like a more idealistic form of documentary. Creators of this style came from a journalistic tradition and claimed that objectivity is possible. According to Jack Ellis, “An approach now called direct cinema was pioneered by Drew Associates in the Close-Up! Series on ABC-TV…. Its tenets were articulated most forcefully by Robert Drew and, especially, by Richard (“Ricky”) Leacock. The Drew-Leacock approach falls within the reportage tradition, coming from Drew's background in photo-journalism and Leacock's experience as a documentary cinematographer” (223). Direct cinema differs from cinema verité in its assumption that a pure experience is possible. Direct cinema, as a type of journalism, looks for stories with an inherent beginning, middle, and end.

An American Family. PBS. WNET, New York. 1973.

Cawelti, John G. Apostles of the Self-Made Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965.

Ehrenreich, Barbara. The Hearts of Men. Garden City, NY: Anchor/Double-day, 1983.

Ellis, Jack C. The Documentary Idea: A Critical History of English-Language Documentary Film and Video. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1989.

Gilbert, Craig. “Reflections on An American Family, I.” New Challenges for Documentary. Ed. Alan Rosenthal. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988. 191-209.

———. “Reflections on An American Family, II.” New Challenges for Documentary. Ed. Alan Rosenthal. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988. 288-307.

“Lance Loud! A Death in an American Family.” 2002. PBS Online, March 18, 2005, www.pbs.org/lanceloud/.

Landrum, Jason, and Deborah Carmichael. “Jeffrey Ruoff's An American Family: A Televised Life: Reviewing the Roots of Reality Television.” Film & History 32.1 (2002): 66-70.

Macdonald, Ross. The Underground Man. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971.

Reich, Charles A. The Greening of America. New York: Random House, 1970.

Ruoff, Jeffrey. “An American Family”: A Televised Life. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Shearer, Harry. Review of An American Family: A Televised Life. By Jeffrey Ruoff. Wilson Quarterly 26.3 (2002): 118-119.

The Real World. MTV. 1992-.