Reality television shows are reframing ideas of the family in U.S. culture. The genre titillates by putting cultural anxieties about the family on display, hawking images of wife swapping, spouse shopping, and date hopping. Its TV landscape is dotted with programs about mating rituals, onscreen weddings, unions arranged by audiences, partners testing their bonds on fantasy dates with others, family switching, home and family improvement, peeks into celebrity households, parents and children marrying each other off on national television, and families pitching their lives as sitcom pilots. Though obviously not the only recurring theme pictured, family is one of the genre's obsessions. Scholars have begun to draw attention to certain questions surrounding family, gender, and sexuality, but we have yet to address fully how the genre debates and reshapes the family or to account for the centrality of that theme in reality programming. This discussion of the family is important, since TV has always played such a vital role in both shaping and reflecting fantasies of the American family.

Using historicized textual analysis, this essay demonstrates how the reality TV genre both reflects and helps shape changing “American family” ideals. A significant number of reality shows picture a seemingly newfound family diversity. For every traditional “modern nuclear family,” with its wage-earning father, stay-at-home mother, and dependent children, we see a panoply of newer arrangements, such as post-divorce, single-parent, blended, and gay and lesbian families. What is the significance of this family diversity as a recurring theme in factual programming? Concurrent with images of demographic change, we also see a familiar rhetoric of the “family in crisis.” Witness the emergency framework of Nanny 911 (a British nanny must save inept American parents who are at their breaking point) or Extreme Makeover: Home Edition (a design team must renovate the home of a family otherwise facing disaster). Their premise is that the American family is in trouble. Many scholars have noted how the family has constantly been described as being in crisis throughout its historical development—with the calamity of the moment always reflecting contemporaneous sociopolitical tensions (Gordon 3). The idea of crisis has been used to justify “family values” debates, which usually involve public policy and political rhetoric that uses moral discourses to define what counts as a healthy family.

I would argue that reality programs focused on the familial settings and themes implicitly make their own arguments about the state of the American family, entering long-running family values debates. In their representation of family diversity (which different series laud or decry) and in their use of family crisis motifs, reality narratives capture a sense of anxiety and ambivalence about evolving family life in the United States. Reality TV markets themes about our current period of momentous social change: the shift from what sociologists term the “modern family,” the nuclear model that reached its full expression in the context of Victorian-era industrialization and peaked in the postwar 1950s, to the “postmodern family,” a diversity of forms that have emerged since then. Indeed, a key theme in reality TV depictions is that family is now perpetually in process or in flux, open to debate. Social historians define the modern family as a nuclear unit with a male breadwinner, female homemaker, and dependent children; its gendered division of labor was largely only an option historically for the white middle class whose male heads of household had access to the “family wage.”1 This form was naturalized as universal but was never the reality for a majority of people, even though it was upheld as a dominant cultural ideal.2 Diverse arrangements have appeared since the 1960s and 1970s, constituting what the historian Edward Shorter termed “the postmodern family.” New familial forms have emerged, spurred by increases in divorce rates and single-parent households, women's entrance into the labor force in large numbers after 1960, the decline of the “family wage,” and the pressures on labor caused by postindustrialism and by globalization.3

Taken as a whole, reality series about the family alter some conventional familial norms while reinforcing others. I would agree with critics such as Tania Modleski and Sherrie A. Inness, who argue that popular culture texts that address issues such as gendered roles and the real contradictions in women's lives often both challenge and reaffirm traditional values (Modleski 7-9, Inness 178-179). These reality programs picture some updated norms (frequently, the edited narratives validate wider definitions of familial relations or urge men to do more domestic labor). The genre's meditation on the shift in norms is not radical, however, because it occurs within TV's liberal pluralism framework. Various programs construct their own sense of the contradictions of family life, such as tensions involving women juggling work and child care, gender role renegotiations, further blurring of public and the private “separate sphere” ideologies, racialized family ideals, and fights about gay marriage. Such shows celebrate conflict, spectacularizing fraught kinship issues as a family circus in order to draw more viewers and advertising, but they most often resolve the strife into a liberal pluralist message by episode's end (for example, using the liberal discourse of individualism to represent racism as an interpersonal conflict that can be resolved between individuals through commonsense appeals rather than as a structural social issue).4

I would contextualize these themes both in terms of television's long history as a domestic medium and in reference to ongoing family values battles. The new household models and demographic changes, such as increased divorce rates, sparked a political backlash beginning in the 1970s: the family values media debates that have intensified since the 1990s. These skirmishes, such as Dan Quayle's attack on the sitcom character Murphy Brown as a symbol of unwed motherhood in the 1992 presidential debates, are an important sociohistorical context for the current reality programming trend. For my purposes here, I date the full advent of the current genre to the premiere of MTV's The Real World in 1992, although related forerunners like police and emergency nonfiction series emerged in the late 1980s, and factual programming has, of course, been around since the medium's origins.5 Though critics debate the looseness of the term reality TV as a genre, I use it to refer to factual programming with key recurring generic and marketing characteristics (such as unscripted, low-cost, edited formats featuring a mix of documentary and fiction genres, often to great ratings success).

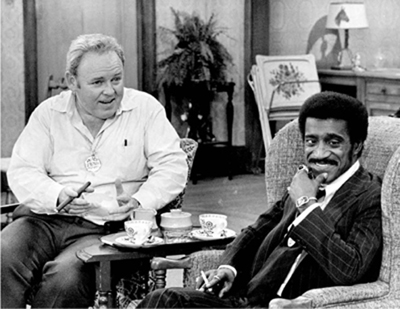

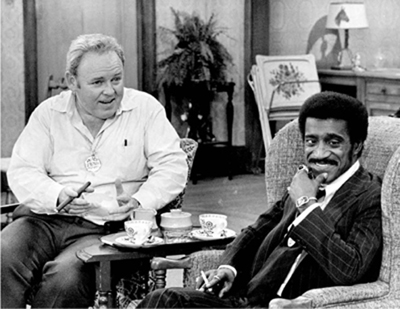

The links between TV and the family are foundational, as long-running research on television and the family has established. The television historian Lynn Spigel has shown how early TV developed coextensively with the postwar suburban middle-class families that the medium made into its favored topic and target audience. The historian Stephanie Coontz has noted how current nostalgia for the nuclear family ideal is filtered through 1950s domestic sitcoms like Leave It to Beaver.6 As critics have illustrated, family shows comment not only on society's basic organizing unit but also on demographic transformations by tracing their influence on the family. Ella Taylor traces a family crisis motif in 1970s series such as All in the Family, The Jeffersons, and One Day at a Time, noting network efforts to generate socially “relevant” programming to grab a targeted middle-class demographic as well as to respond to social changes prompted by the women's and civil rights movements (2-3). Herman Gray, likewise, in Watching Race, has detailed assimilationist messages, reflecting prevailing social discourses, in portraits of black families in the 1980s, like The Cosby Show. I demonstrate how reality TV opens a fresh chapter in TV's long-running love affair with the family—the medium has birthed a new genre that grapples with the postmodern family condition.

All in the Family (CBS) ran from 1971 to 1979. Shown here are Carroll O'Connor as Archie Bunker and Sammy Davis Jr. in a guest appearance on the show. The series was known for its socially relevant programming targeted to middle-class white audiences. Courtesy of CBS/PhotoFest.

Reality TV mines quarrels about family life, producing, for example, gay dating shows (such as Boy Meets Boy, 2003) at the precise moment of national deliberations over gay marriage. The genre sinks its formidable teeth into these controversies. Much as domestic sitcoms did in the 1950s, it gives us new ways of thinking about familial forms in relationship to identity categories like gender and sexuality or to larger concepts like citizenship and national identity. It does so in part by illuminating the cultural tensions underlying family values debates, such as the family's contested nature as a U.S. institution that legitimates social identities, confers legal and property rights, and models the nation imagined as a family, whether a “house united” or a “house divided.”

Tracing recurring tropes in reality programs about the family, I would argue for four key narrative stances toward social change: nostalgia for the traditional modern nuclear family; promotion of a new, modified nuclear family norm in which husband and wife both work outside the home; a tentative, superficial embrace of family pluralism in the context of liberal pluralism; and an open-ended questioning of norms that might include a more extensive sense of family diversity. These narrative trends are particularly evident in some specific reality subgenres: family-switching shows (Trading Spouses, Wife Swap, Black.White, Meet Mister Mom); observations of family life (The Real Housewives of Orange County; Little People, Big World); celebrity family series (The Osbournes, Run's House, Meet the Barkers, Being Bobby Brown, Breaking Bonaduce, Hogan Knows Best); home and family makeover programs (Extreme Makeover: Home Edition, Renovate My Family); family workplace series (Dog the Bounty Hunter, Family Plots, Family Business); family gamedocs (Things I Hate about You, Race to the Altar, Married by America, The Will, The Family); parenting series (Nanny 911, Supernanny, Showbiz Moms and Dads); and historical reenactment programs with family settings (Colonial House, Frontier House).

These programs watch middle-class “average joes,” perhaps the viewer's friends and neighbors, navigate the shoals of domesticity, grappling with cultural problems such as the tension between kinship and chosen bonds, the effect of the media on the family, and the state's efforts to define “family” as a matter of national concern and to legislate access to marriage rights. Ultimately, these shows convey a kind of emotional engagement, what Ien Ang would term “emotional realism,” regarding changes in family structures in the United States, capturing a recent shift in middle-class attitudes toward the American family, a change in what Raymond Williams would call that group's “structure of feeling” (Ang 47).

Reality TV spectacularizes such issues as a family circus in order to draw viewers and sell advertising. Part of its vast ratings appeal stems from the fact that it portrays real people struggling with long-running cultural problems that have no easy answers: tensions in the ties that bind, between kinship and chosen bonds, between tradition and change; personal versus social identity; and competing moralities. The genre explores angst about what “the American family” is in the first place.7 Such widespread worries are not surprising, given that this unit is a social construction that is notoriously difficult to define, particularly since it has historically encoded gendered roles and hierarchies of class, race, and sexuality that define ideas of social acceptance, a crucible for selfhood and nationhood. Critics have noted the regulatory nature of the modern nuclear family model, and official discourse has traditionally framed that unit as a white, middle-class heterosexual norm to which citizens should aspire (Chambers).

Reality TV does not explicitly solve those family values disputes. Instead, it concentrates on mining the conflict between the two familial forms, one residual and one emergent. Rather than answering questions about what the postmodern family will become, it rehearses sundry arguments about how the familial unit is getting exposed, built up, torn down, and redefined. Some programs offer wish-fulfillment fantasies, smoothing over rancorous public squabbles and social changes but not resolving those tensions.

For example, Bravo's Things I Hate about You (2004), reflecting this panoply, turns domesticity into a sport in which snarky judges determine which member of a couple is more annoying to live with and partners happily air their dirty laundry on TV (sometimes literally). One week we see an unmarried heterosexual couple with no children, the next a gay domestic partnership. No one model dominates. The series fits all these groupings into the same narrative framework: a story about family and the daily irritations of domesticity. Other reality programs chart a fading modern nuclear family ideal. The dating show subgenre continues to spawn a vast number of formats and high audience ratings. While series like The Bachelor romanticize young people trying to find their “true love,” marry, have children, and embody the traditional family ideals of their parents’ generation, they also implicitly register the shifting of those norms, not least because the cast members also see the overwhelming majority of these arranged TV couplings and engagements dissolve, just as more than 50 percent of marriages in the United States end in divorce.8

Drawing on the sociopolitical and media history of the family values debates, reality TV offers viewers the voyeuristic chance to peer into other people's households to see how all this cultural ruckus is affecting actual families. As the genre takes up the modern and postmodern family in various ways, it often explicitly engages with public policy and media discussions. The way reality serials address familial life illuminates an uneasy shift from modern nuclear family ideals to the postmodern reality of diverse practices.

One main trend in reality programming is for series to look backward with a nostalgia for the modern nuclear family that reveals the instability of that model. Some series revert to older concepts, such as the sociologist Talcott Parsons's mid-twentieth-century theories of functional and dysfunctional family forms. He argued that the modern nuclear family's function under industrialized capitalism was to reproduce and socialize children into dominant moral codes, as well as to define and promote norms of sexual behavior and ideas of affective bonds associated with companionate marriage. Dysfunctional families that deviated from norms were functionalism's defining “Other,” and some critics argue that this paradigm still influences sociological research on family life (Stacey, In the Name of the Family; Chambers 1-32; Every). Pop psychology concepts of functionalism and dysfunctionalism certainly circulate widely in today's mass media, and we see their influence in reality shows.

A particularly apt example is the spouse-swapping subgenre, which includes shows like ABC's Wife Swap. The titillating title implies it will follow the wild exploits of swingers, but the show instead documents strangers who switch households and parenting duties for a short period. Similarly, on Fox's Trading Spouses: Meet Your New Mommy (the copycat show that beat ABC's to the air), two parents each occupy the other's home for several days. Both series focus on the conflict between households, revealing a fierce debate among participants as to whose family is healthier, more “normal,” or more “functional.” On Trading Spouses, one two-part episode swaps mothers from white suburban nuclear families, each comprising a husband, a wife, two kids, and a dog (“Bowers/Pilek”). Both clans want to claim modern nuclear family functionality for themselves, but economic tensions ensue, even though each woman describes her family as middle class. A California mom with an opulent beach house judges her Massachusetts hosts, with their modest home and verbal fisticuffs, as unkempt, whereas her outspoken counterpart deems the beach household materialistic and emotionally disconnected. Each woman characterizes the other family as dysfunctional. Their conflict reveals not only the degree to which many people still use these older ideals as their own measuring sticks, here staged as issues such as tidiness or appropriate levels of emotional closeness, but also the tenuousness of those ideals, given the intense contradictions between two supposedly functional families.

Through the premise of swapping households or roles for several days, these programs explore Otherness by having participants step into someone else's performance of kinship behaviors. In so doing, they illuminate identity categories that are performed through the family. This dynamic was perhaps most notably executed on the series Black.White, which used makeup to switch a white and black family for several weeks and staged racial tensions between them. In this subgenre more generally, participants reproduce a version of their counterparts’ social identity. Thus, the switch highlights the arbitrariness of such identity performances. Since the shows allow the participants to judge each other, family appears as a topic of open-ended debate.

These programs depend on conflict generated by social hierarchies of race, class, gender, and sexuality, and they privilege white male heteronor-mativity. Their narratives often focus on gender, encouraging men to take on more child care and domestic chores. Yet they still rely on ideologies of gender difference to explain household units and to reaffirm the mother's role as nurturer-caregiver. By absenting the mother, the wife-swap series imply that husbands and kids will learn to appreciate the woman of the house more.

These series encourage a liberal pluralist resolution to conflicts, one that upholds an easy humanist consensus, or what critics term “corporate multiculturalism,” which markets diversity as another product rather than picturing and validating substantive cultural differences. The framing narratives resolve competing ideas, most often by defining as normal a modified modern nuclear family (two working parents). In shows about alternative households, for example, the narratives sympathize with the single mom or the lesbian couple but uphold the intact nuclear family as more rational and functional. Yet the narratives also often critique participants’ overly intense nostalgia for the bygone modern nuclear ideal, and they sometimes allow for some validation of alternative models, such as an African American extended family. They depend on sensationalism and conflict over values to spark ratings.

This open warfare over functional and dysfunctional families includes a huge helping of nostalgia, as epitomized by a series like MTV's The Osbournes. This hit show supports the sense that if the modern nuclear ideal has been replaced by a diversity of family forms, U.S. culture still has an intense nostalgia for the older norm. Is nostalgia for the fantasy nuclear unit actually a defining characteristic of the postmodern family? It is for The Osbournes. Viewers flocked to the show because it juxtaposes a famously hard-living, heavy-metal family with classic sitcom family plotlines, edited to emphasize the irony of seeing the cursing, drug-abusing rock star Ozzy and his brood hilariously butchering Ozzie and Harriet-style narratives.

The entertainment press dubbed them “America's favorite family,” and a series of high-profile magazine cover stories tried to explain the show's wild popularity by pointing to how the Osbournes “put the fun in dysfunctional.” The show garnered MTV's highest-rated debut at that time and enjoyed some of the strongest ratings in the channel's history during its run from 2002 until 2005.9 Part of the appeal lies in how the Osbournes seem to capture on videotape a more accurate sense of the pressures of family life, ranging from sibling rivalry to teen sex and drug use to a serious illness (such as Sharon's cancer diagnosis and treatment). Even though their fame and fortune make them unlike home viewers, the family can be related to because of the struggles they confront openly. Likewise, they reflect current family diversity because they are a blended family; their brood includes their son and two daughters (one of whom declined to appear on the series), Ozzy's son from his first marriage, and their children's teen friend whom they adopted during the show after his mother died of cancer. Ozzy himself suggested that he did the series in order to expand understandings of the family: “What is a functional family? I know I'm dysfunctional by a long shot, but what guidelines do we all have to go by? The Waltons?” (Hedegaard 33). Ozzy here is both arbiter and agent; he notes TV's power to define a range of meanings for the family, whether through the Waltons or the Osbournes.

Yet even while the program's narrative meditates on entertaining dys-functionality and new family realities, it also continuously tries to recuperate the Osbournes as a functional nuclear family. Story arcs are edited to frame them as dysfunctional (cursing parents, wild fights, teenage drug use), but also to rescue them as functional; there are sentimental shots of the family gathered together in their kitchen or clips of them expressing their love and loyalty despite the titillating fights. Even though Ozzy tells his family they are “all f—ing mad,” in the same breath he says he “loves them more than life itself” (“A House Divided”). The edited narrative purposefully emphasizes the bonds of hearth and home, sometimes trying to establish functionality by cutting out serious family events that would have made Parsons blanch: Ozzy's drug relapse, severe mental illness, and nervous breakdown during taping; trips to rehab by Jack and Kelly, the son and daughter; and Sharon's temporary separation from Ozzy over these issues. Press coverage of the show and fan response likewise emphasized a recuperative dynamic, both looking for the loveable, reassuring nuclear family beneath the rough exterior. As an Entertainment Weekly cover story noted, Ozzy Osbourne went from being boycotted by parents’ groups in the 1980s for bat biting and supposedly Satanic lyrics to being asked for parenting advice from men's magazines (Miller). Thus, even while registering the limitations of Parsons's model, the series still tries to rehabilitate this celebrity family as functional. As a result, this program and others like it explore the postmodern family, but at the same time they look back wistfully on the old modern nuclear paradigm.

The Osbournes is also a prime example of a program that explicitly comments on the influence of television on family ideals. Part of the show's insight comes from registering how much the media, whether the popular music industry or television, have shaped this family unit. Brian Graden, then president of MTV Entertainment, described the program's draw as “the juxtaposition of the fantastical rock-star life with the ordinary and the everyday”; summarizing one episode, he laughed, “Am I really seeing Ozzy Osbourne trying to turn on the vacuum cleaner?” Graden noted that after they collected footage on the Osbournes, producers realized that “a lot of these story lines mirrored classic domestic sitcom story lines, yet with a twist of outrageousness that you wouldn't believe” (Miller). Watching footage of their daily experiences, Graden immediately views them through the lens of earlier TV sitcoms; everywhere he looks, he sees the Cleavers on speed. And the show Graden's company makes of this family's life might one day comprise the plotlines other viewers use to interpret their own experiences in some way. After their smash first season, the Osbournes were feted at the White House Correspondents’ dinner and managed to parlay such national attention into more entertainment career opportunities, with a new MTV show, Battle for Ozzfest (2004-), hosted by Sharon and Ozzy and featuring bands competing to join their summer tour; Sharon's syndicated talk show that ran for one season (2003-2004); and their children's slew of TV, movie, and music ventures growing out of their exposure from the reality program.

Though most families could not follow the Osbournes into celebrity, what many do share with the rockers is the knowledge that TV significantly shapes familial ideals. This media awareness marks a parenting trend. In their recent audience study of family television-viewing practices, Stewart M. Hoover, Lynn Schofield Clark, and Diane F. Alters found that parents had a highly self-reflexive attitude toward the media. They were well conscious of how the mass media both reflect and shape social beliefs, and they worried about the daily influence of television in their children's lives. Hoover et al. identified this media anxiety as part of what they term “self-reflexive parenting” behaviors stemming from increased concerns about child rearing since the 1960s. They see this model of parenting as part of what Anthony Giddens calls the project of self-reflexivity in modernity, in which people are reflective about their interaction with the social world as they continually incorporate mediated experiences into their sense of self (Hoover et al., Giddens).

The two most prominent parenting shows, Nanny 911 and Super-nanny, portray a severe tension between modern nuclear ideals and postmodern variations. They suggest that threats from within and outside the American family are destabilizing it to the extent that it must be saved by the no-nonsense child-rearing philosophies of its colonial parent, dispatched in the form of a Mary Poppins-style nanny. They implicitly refer to nineteenth-century domestic science ideals as well as mid-twentieth-century sociological theories, such as Talcott Parsons's schema of functionalism and dysfunctionalism. As a case study, these shows clarify how anxiety about expertise and professionalism contributes to consumer behavior (hire a nanny to fix your unruly children, buy the series’ tie-in books as magic talismans). They relate to other programs, such as the Learning Channel's suite of shows about parenting and childbirth, all of which resort to expert advice and affirm conventional modern nuclear family forms. They demonstrate how reality programming can be framed as a pedagogical site. As Annette Hill has found, many viewers see reality TV as an opportunity for social learning. Ron Becker has shown that these nanny programs also display neoliberal rhetorics because they focus on the need for the family to be autonomous to help legitimate the shift to post-welfare-state governance in contemporary America.

By way of contrast, there is a more marginal satire of parenting found in Bravo's suite of shows Showbiz Moms and Dads, Sportkids Moms and Dads, and Showdog Moms and Dads. These programs follow parents whom the edited narratives present as overly protective or controlling. They spend too much on consumer goods, live their dreams vicariously through their kids, suffer from intractable generational tensions, and sometimes treat their pets like children to an extreme extent. The shows denaturalize parenting behaviors and elucidate them as performative roles. This ironic treatment fits Bravo's marketing and target audiences.

Moving from parenting to a different element of domestic science rhetoric, home makeover shows establish an ideological tie between a rationalized home and a healthy family, a connection further blurring the traditional public-private split. In the blockbuster Extreme Makeover: Home Edition and its short-lived imitator, Renovate My Family, teams of experts evaluate family life, advising participants and home viewers alike in family values as they anxiously gauge new household forms. On both series, it is families that depart from the modern nuclear norm that need assistance (single-parent, blended, impoverished, orphaned).

Instead of advocating government aid in the form of low-income housing or social welfare safety nets, these series perform a kind of neo-liberal privatization and outsourcing, which speaks to a diminishing public sphere. Through the largesse of their corporate advertisers, these programs will provide needy families with domestic palaces and consumer goods that will effortlessly heal any family troubles. In the case of Renovate My Family, the program uses pop psychology (and the kind of therapeutic address Mimi White reads as saturating television in general) to counsel families on problems like alcoholism, threats of divorce, or withdrawn children. It is no surprise that the host is Jay McGraw, son of famous TV “life coach” Dr. Phil McGraw, tough love guru. In this reality format, as critics have shown, the moment of revealing the new home is supposed to spark emotional realism in the family, the weeping moments of “authenticity” Hill has noted viewers look for in reality programs. Neoliberalism reaches new heights in Extreme Makeover when First Lady Laura Bush appears on one episode to laud their work, and a series of other episodes sends the design team to hurricane-ravaged Gulf Coast areas to “help out” where the government has not. In this discussion I join a conversation of scholars such as John McMurria, Gareth Palmer, and Jennifer Gillan, who have begun illuminating the neoliberal political economy in these home makeover programs. Gillan asserts the Extreme Makeover series models neoliberal citizenship for viewers by invoking American frontier mythology and an idea of “neighborliness” when, in the season 2 finale, it helps build a new home and a community center for the family of the rescued POW Jessica Lynch's fallen Navajo comrade, Lori Piestewa, assuaging guilt over more Native “vanishing Americans.”

Another main trend in reality TV is a push forward to an uncertain present and future, an exploration of emergent models of the postmodern family, following single parents and patchwork households as they try to negotiate interpersonal relationships and constant redefinitions of the family. A program like Bravo's Showbiz Moms and Dads follows several single mothers (along with other family types) as they pursue the dream of fame and celebrity for their children, achieved to some degree for these families by being on the series. Another high-profile single-mom series is a reality take on The Sopranos, A&E's Growing Up Gotti. Cameras follow Victoria Gotti, daughter of the deceased crime boss John Gotti, as she mothers her three rowdy teenage sons. She launches the show by pointing out, in case there was any question, that they are “not your typical family.” The show plays on the ironic juxtaposition of the mafia “Family” background with the daily toil of home life with teenagers.

As part of a similar critique of older family ideals, some programs simply meditate on threats to the continued survival of the nuclear family, tapping into fears for the sake of ratings. These programs imagine the threat to the nuclear ideal in terms of divorce (programs pairing divorcees for another tilt at the marriage wheel, such as Who Wants to Marry My Dad? and Who Wants to Marry My Mom?), infidelity (Temptation Island, The Ultimate Love Test), lack of commitment (Paradise Hotel, Forever Eden, Love Cruise), the lure of money over romantic entanglement or family bonds (For Love or Money, Joe Millionaire, Mr. Personality, The Family), or the pressures of fame (Newlyweds: Nick and Jessica, ‘Til Death Do Us Part: Carmen and Dave, Meet the Barkers, Diary Presents Brandy: Special Delivery).

Some programs turn the instability of the nuclear family into sensationalized plot twists. One season of Big Brother included the surprise gimmick of having a half brother and half sister as contestants in the house together; the two did not know of each other's existence, since the sister grew up with their father and the brother had never met him. Producers, upon realizing their connection when both applied to the show, put them in the house together, then used the newfound blood bond to generate high drama in the Machiavellian competition game as the two discovered they were siblings. Fox turned the search for one's birth parent into reality fodder with Who's Your Daddy? which had an adopted daughter attempt to pick out her biological father from a group of men. That program incited protests from adoption groups for trivializing the process, and the poor taste quotient reached a new high on CBS's The Will, where cutthroat relatives competed for a patriarch's inheritance, which also sparked protests for insensitivity and was canceled after one episode (Smith).

It is notable that several key reality programs historicize the development of familial ideals and their inequities. “Historical experience” programs till this ground. Linking family history to a broader framework of U.S. history, this subgenre sends participants back in time to reenact earlier lifestyles and pinpoints the exclusionary nature of white patriarchal family models and the social institutions founded on them. On PBS's House series, for example, many of the female, African American, or gay and lesbian participants become frustrated with the historical roles they had to fit into on Colonial House or the Victorian-era Frontier House (as they materially register in some way what it would have been like to be disenfranchised women, enslaved blacks, or sexual dissidents facing a penalty of death). As they explore a different epoch and its material conditions, these series often examine how the family unit came to be seen as the fundamental unit of social organization, an instrument for colonization and imperialism, or a model for the modern nation-state (witness CBC's Pioneer Quest in Canada as well BBC/PBS House programs set in England: Manor House, 1900 House, and The 1940s House).

I would argue that reality TV is the popular media form with the most to say about the current status of the American family. The television historian Lynn Spigel has shown that early TV developed coextensively with the post-World War II suburban middle-class family—a specific kind of modern nuclear family model the medium made into its favored subject and audience. As Spigel notes, while sociologists like Talcott Parsons were arguing in the 1940s and 1950s that the modern nuclear family is the social form best suited to capitalist progress, the new electronic TV medium targeted the postwar white, middle-class families flocking to the suburbs, encouraging the development of the modern family as a consumer unit.

As a new genre now exploring the self-conscious imbrication of family and the media as one of its main themes, reality TV raises vital issues of marketing and consumerism. If television enters the home to become, as Cecelia Tichi has shown, “the electronic hearth” around which the family gathers, so too does the family envision itself through the tube. TV addresses the family as ideal viewer, imagined community, and the basis for democracy mediated through mass communication; the nation is figured as a collective of families all watching their television sets (a collective that can now exercise its democratic rights by calling in to vote for a favorite singer on American Idol). If the domestic sitcom was like an electronic media version of a station wagon trundling the modern family along in the 1950s, reality TV is the hybrid gas-electric car of the postmodern family today.

As reality programs ponder the status of American families now, they also enter into the family values media debates in ways that speak to the politicization of the family. Coontz has proven that the family has been seen as the moral guide for the nation ever since the late nineteenth century, from Theodore Roosevelt's insistence that the nation's future rested on the “right kind of home life” to Ronald Reagan's assertion that “strong families are the foundation of society” (94). As the media studies critic Laura Kipnis notes in her recent witty polemic against modern coupledom, alternative models of organization trouble the social contract, so it is no mistake that “the citizenship-as-marriage analogy has been a recurring theme in liberal-democratic political theory for the last couple of hundred years or so, from Rousseau on” (23-24).

Since family opens such a space of performed social identity, often articulated through narrative, it is not surprising that television has always been one of the key battlegrounds for familial ideas. In her study of how 1970s television responded to the perceived cultural crises of the time, the historian Ella Taylor argues that TV families of the 1950s and 1960s were largely portrayed as harmonious, the building blocks of society and a consensus culture (Ozzie and Harriet, Leave It to Beaver), whereas 1970s families appeared under siege and in crisis because of significant changes, such as a spike in divorce rates during that decade (All in the Family, One Day at a Time). For Taylor, 1980s TV witnessed a variety of family forms but was dominated by a retreat to nostalgic intact nuclear families (The Cosby Show, Family Ties) (2-3). As other critics have since noted, 1990s TV families continued in the 1980s vein (Home Improvement, Seventh Heaven) but also satirized family ideals through dysfunctional family sitcoms (The Simpsons, Married with Children). Meanwhile, popular fictional shows in the early 2000s seem more explicitly to debate the variety of family forms emerging with recent demographic trends. Witness ABC's popular nighttime soap, Desperate Housewives (2004-), which initially garnered more than 20 million viewers and top ratings; it depicts women struggling with their roles in a range of settings, including intact nuclear families, post-divorce families, single-parent households, and childless families.10 In terms of audience reception of these TV images over time, a series of pioneering “family television” studies since the 1970s has shown how many families actually use television in diverse ways to help shape subjectivity (Morley, Family Television, Home Territories).

Reality TV itself has always been a remarkably familial genre, though the earlier examples of unscripted programming that display a similar obsession with the family do so in a different sociohistorical context. As Jeffrey Ruoff notes, An American Family is still the most widely circulated direct cinema documentary in U.S. history. It aired just as large-scale social movements such as women's liberation, civil rights, and gay rights were generating upheavals, and it put social changes like the soaring divorce rate into focus by charting an individual family's response to its time period. Earlier formal precursors also include the long-running madcap Chuck Barris game shows such as The Newlywed Game (first aired in 1966) and The Dating Game (premiered in 1965), which turned aspects of marriage and dating into farce.11

Not surprisingly, recent public arguments about family and marriage often turn reality TV into prime fodder. Conservative groups frequently protest reality fare. Most spectacularly, complaints made by conservative activists from the Parents Television Council prompted the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to threaten Fox with a fine of $1.2 million, the largest to date, for Married by America when it was on the air. The show had audiences pick mates for couples who could have gotten married on air (though none did and all the arranged couples stopped dating after the show). The protestors found it a vulgar trivialization of the institution of marriage (Rich).

On the flip side of the coin, progressive thinkers have used reality TV to make public arguments advocating a greater diversity of marriage and household arrangements. The cultural theorist Lisa Duggan, in a 2004 Nation article, explores public policy about state-sanctioned marriage in the context of the debates over gay marriage, critiquing, for example, “marriage promotion” by both the Clinton and the Bush administrations as a way to privatize social welfare. Duggan calls for a diversification of democratically accessible forms of state recognition for households and partnerships, a “flexible menu of choices” that would dethrone the privileged civic status of sanctified marriage and “threaten the normative status of the nuclear family, undermining state endorsement of heterosexual privilege, the male ‘headed’ household and ‘family values’ moralism as social welfare policy.” She uses reality TV as an example of current dissatisfaction with gendered, “traditional” marriage and a marker of its decline, describing “the competitive gold-digging sucker punch on TV's Joe Millionaire” (which tricked eager women into believing they were competing to marry a millionaire) as an entertainment culture indicator of the statistical flux in marriage and kinship arrangements. She argues that the franchise confirms social anxiety that “marriage is less stable and central to the organization of American life than ever” (1). Notably, Dug-gan pairs her Joe Millionaire example with the pop singer Britney Spears's rapidly annulled 2004 Las Vegas wedding (to a high school friend, Jason Alexander) as similar social indexes; the celebrity life and the reality show plot represent similar kinds of evidence, both equally real (or equally fake) in current entertainment media culture.

Regardless of the different ways the genre enters into existing political discussions, what is striking is that it continually becomes a site for family values debates. A case in point is how a couple competing on the sixth season of CBS's The Amazing Race (2005) made headlines because critics accused the husband of exhibiting abusive behavior toward his wife in the series footage. The couple, Jonathan Baker and Victoria Fuller, made the rounds of talk shows to protest that characterization, but the main dynamic of press coverage has been to turn them into a teaching moment. Both went on the entertainment TV newsmagazine The Insider and were asked to watch footage of themselves fighting and answer the charge that it looked abusive; Baker responded: “I'm a better person than that. I have to say I had a temper tantrum, you know, I pushed her, I never should have, and you know, I regret every moment of it and you know what, hopefully that experience will make me a better person. That's our story line, you know, that's who we were on television. That's not who we are in real life” (Insider).

Such a framing of that reality TV footage is emblematic: the show is perceived as somewhat mediated and constructed but still real enough to warrant a press debate. Through a bit of internal network marketing, Dr. Phil actually made them the topic of one of his CBS prime-time specials on relationships. Noting that the show sparked reams of hate mail and even death threats toward the couple, Dr. Phil explicitly argues that America was watching the couple and wants to debate them in TV's public sphere. At the outset of the interview, he invokes and calls into being an imagined national public, saying, “America was outraged and appalled by what they've seen.” After he exhorts the husband to correct his behavior, he concludes, “So America doesn't need to worry about you?”(Dr. Phil Prime-time Special). Dr. Phil does not completely buy Baker's argument that he was only acting aggressively for the camera or that the editing heightened his behavior, and he admonishes the man for exhibiting bad behavior in any context, mediated or not. Dr. Phil is well aware of the construction of images that he himself perpetuates, and he even draws attention to how Baker tries to manipulate this on-camera interview by coaching his wife, yet he insists on a substantial component of actuality in all these depictions. In the press and popular response, the gamedoc show couple becomes a paradigmatic reality TV family example that can be used to analyze the state of the American family more generally.

Ultimately, reality programs add a new wrinkle to television's family ideas. The genre illuminates how the current definition of the family is up for grabs, and reality TV enters the debate arena in force. Instead of having nostalgia for the Cleavers as a model of the modern American family, viewers might one day have nostalgia for the Osbournes as a model of the postmodern American family. The amplified truth claims of reality TV comment on the social role of television itself as an electronic medium offering “public scripts” that, as the medium evolves, viewers increasingly want to interact with on the screen and participate in themselves.

1. Historians now question how far back to date the nuclear family. Many assert the need to nuance the long-held theory of a total family revolution from premodern to modern families between the 1780s and 1840s as a consequence of industrialization. Coontz argues the conventional idea that industrialization ushered out the extended family does not hold true when one considers that the highest numbers of extended families occurred in the mid-nineteenth century. What most scholars do agree on, however, is that the white, middle-class, nuclear family model became idealized and codified in the Victorian period, even when the reality of people's lives differed drastically, and that it has been used to regulate ideas of family and behavior since then (Coontz 12).

2. Two-parent households were the majority only from the 1920s to 1970s, and the modern nuclear family represented only a minority of those households (Frey et al. 123-124).

3. See Stacey, Brave New Families 3-19; Cott. Stacey notes that more children now live with single mothers than live in modern nuclear families (In the Name of the Family 45).

4. Jon Kraszewksi has provided a helpful analysis of the discourse of liberalism that, for example, MTV explicitly promotes (Kraszewski 192).

5. Though we know unscripted programming has been around since television's earliest days, the date of the current reality trend's onset is a matter of critical debate. To cite representative examples, Kilborn dubs America's Unsolved Mysteries (1987) the original impetus for current reality TV, whereas Jermyn points to Crimewatch UK (1984-) (Kilborn; Jermyn 75).

6. Coontz and other historians have demonstrated that the 1950s fantasy family was not only the product of a statistical anomaly (unusually high rates of marriage and childbearing after World War II), but was also rooted in damning contradictions and inequities, such as the imperative for women to return to the home after wartime labor and wholly subordinate their needs to those of their husbands and children, which sparked the original desperate housewives and high rates of alcoholism (Coontz 37; see also May 11).

7. I use American to refer to the United States specifically, though I am well aware of problems with this shorthand; as Jan Radway notes, America more properly refers to all the Americas.

8. Census data indicate that 50 percent of first marriages and 60 percent of second ones are likely to end in divorce within forty years (Coontz 3).

9. The March 3, 2002, debut had a 2.8 household rating, and the show's ratings eventually exceeded 5 million viewers in the first season, though parts of the subsequent seasons have had lower ratings (Deevoy).

10. The show has at times averaged 13.9 million viewers (“Top 20”).

11. The Newlywed Game aired 1966-1974, 1977-1980, and, as The New Newlywed Game, 1984-1989. The Dating Game ran 1965-1986 and, as The All-New Dating Game, 1986-1989 and 1996-1999.

Ang, Ien. Watching Dallas: Television and the Melodramatic Imagination. London: Routledge, 1985.

Becker, Ron. “‘Help Is on the Way!’ Supernanny, Nanny 911, and the Neoliberal Politics of the Family.” The Great American Makeover: Television, History, Nation. Ed. Dana Heller. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 175-192.

“Bowers/Pilek.” Trading Spouses: Meet Your New Mommy. Fox. August 3, 2004, August 10, 2004.

Chambers, Deborah. Representing the Family. London: Sage, 2001.

Coontz, Stephanie. The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap. New York: BasicBooks, 1992.

Cott, Nancy F. Public Vows: A History of Marriage and the Nation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Deevoy, Adrian. “Ozzy's Summer of Love.” Blender (June-July 2002): 90-96.

Dr. Phil Primetime Special: Romance Rescue. CBS. February 15, 2005.

Duggan, Lisa. “Holy Matrimony!” Nation, March 15, 2004, www.thenation.com/doc.mhtml?i=20040315&s=duggan.

Every, Jo Van. “From Modern Nuclear Family Households to Postmodern Diversity? The Sociological Construction of Families.” Changing Family Values. Ed. Gill Jagger and Caroline Wright. London: Routledge, 1999. 166-179.

Frey, William H., Bill Abresch, and Jonathan Yeasting. America by the Numbers: A Field Guide to the U.S. Population. New York: New Press, 2001.

Giddens, Anthony. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991.

Gillan, Jennifer. “Extreme Makeover Homeland Security Edition.” The Great American Makeover: Television, History, Nation. Ed. Dana Heller. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 193-210.

Gordon, Linda. Heroes of Their Own Lives. New York: Viking, 1988.

Gray, Herman. Watching Race: Television and the Struggle for “Blackness.” Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995.

Hedegaard, Erik. “The Osbournes: America's First Family.” Rolling Stone, May 9, 2002, 33-36.

Hill, Annette. Reality TV: Factual Entertainment and Television Audiences. London: Routledge, 2005.

Hoover, Stewart M., Lynn Schofield Clark, and Diane F. Alters. Media, Home, and Family. New York: Routledge, 2004.

“A House Divided.” The Osbournes. MTV. March 5, 2002.

Inness, Sherrie A. Tough Girls. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999.

The Insider. CBS. January 19, 2005.

Jermyn, Deborah. “‘This Is about Real People!’ Video Technologies, Actuality, and Affect in the Television Crime Appeal.” Understanding Reality Television. Ed. Su Holmes and Deborah Jermyn. London: Routledge, 2004. 71-90.

Kilborn, Richard. “How Real Can You Get? Recent Developments in ‘Reality’ Television.” European Journal of Communications 9 (1994): 421-439.

Kipnis, Laura. Against Love: A Polemic. New York: Pantheon, 2003.

Kraszewski, Jon. “Country Hicks and Urban Cliques: Mediating Race, Reality, and Liberalism on MTV's The Real World.” Reality TV: Remaking Television Culture. Ed. Susan Murray and Laurie Ouellette. New York: New York University Press, 2004. 179-196.

May, Elaine Tyler. Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. New York: Basic Books, 1988.

Miller, Nancy. “American Goth: How the Osbournes, a Simple, Headbanging British Family, Became Our Nation's Latest Reality-TV Addiction.” Entertainment Weekly, April 19, 2002, 25.

Modleski, Tania. Feminism without Women: Culture and Criticism in a “Postfeminist” Age. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Morley, David. Family Television: Cultural Power and Domestic Leisure. London: Comedia, 1986.

—. Home Territories: Media, Mobility and Identity. London: Routledge, 2000.

Radway, Janice. “‘What's in a Name?’ “American Quarterly 51.1 (March 1999): 1-32.

Rich, Frank. “The Great Indecency Hoax.” New York Times on the Web, November 28, 2004, www.nytimes.com/2004/11/28/arts/28rich.xhtml?e x=1102397227&ei=1&en=9736fb1bcb36aee1.

Ruoff, Jeffrey. “An American Family”: A Televised Life. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Shorter, Edward. The Making of the Modern Family. New York: Basic Books, 1975.

Smith, Lynn. “Fox Show ‘Daddy’ Draws Ire.” Los Angeles Times, December 22, 2004.

Spigel, Lynn. Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Stacey, Judith. Brave New Families: Stories of Domestic Upheaval in Late Twentieth Century America. New York: Basic Books, 1990.

———. In the Name of the Family: Rethinking Family Values in the Postmodern Age. Boston: Beacon Press, 1996.

Taylor, Ella. Prime-Time Families: Television Culture in Postwar America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

Tichi, Cecelia. Electronic Hearth: Creating an American Television Culture. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

“Top 20 Network Primetime Series by Households: Season-to-Date 09/20/04-11/28/04.” Zap2It, December 4, 2004, http://tv.zap2it.com/tveditorial/ tve_main/1,1002,272lseasonll,00.xhtml.