In the world of television, if “The Bachelor” or “Fear Factor” isn't your cup of tea, we recommend several alternatives to “reality TV.” Have you ever wished you could step back in time and experience the way people lived in your favorite era of history? Do you long for a slower pace of life where your family could live together on your own homestead and farm your own plot of land? Do you envision the sparkle of a magnificent chandelier in a Regency ballroom where Mr. Darcy might have first laid eyes on Elizabeth Bennet? (www.erasofelegance.com/entertainment/ television2.xhtml)

When the first of the British-themed and -produced historical House series, 1900 House, aired in the United States on PBS in June 2000, the network described the project as “classy voyeurism” and the place where “the sci-fi drama of time travel meets true-life drama.”1 The success of 1900 House has since led to other Anglo-American productions, including 1940s House (2000), Frontier House (2001), Manor House (2002), Colonial House (2003), Texas Ranch House (2006), and even PBS's own version of reality dating (albeit in corsets and tights), Regency House Party (2004). Determined to distinguish the House series from other reality TV programs aired on commercial networks, PBS's producer Beth Hoppe insists that this is the only one “with something to offer. We're exploring history. No one else is doing that.”2

It is true that the producers consult historians and provide rule books and period-appropriate clothing, but it is not always history that drives the series’ ensuing drama. As the above quote suggests, participants and viewers of these shows prefer a Fantasy Island version of the past: family togetherness, chandelier-lit drawing rooms, and heroic endeavors. As the Texas ranchers or Edwardian aristocrats try to live through their particular moment in the past, they perform their assigned roles, and the exploration of history, the so-called goal of the series, becomes a game (de Groot 403). Indeed, the professional historian is rarely visible in the series. When a military historian is invited to the final dinner of Regency House Party to lecture on the Battle of Waterloo, his words are drowned out by music; he is obviously too dull for viewers who prefer to see the developing romances among the guests.

The social historian Tristram Hunt takes issue with reality TV programming that uses history for purposes of “edutainment” and self-discovery. In his essay “Reality, Identity and Empathy: The Changing Face of Social History Television,” Hunt observes that the recent media craze for history suggests a cultural and psychological search for “nourishment” by a secular society. Though more history is certainly being consumed, he adds, “it is far from clear how much is nurturing a deep and abiding sense of the past” (843). Indeed, historical accuracy takes a backseat to the time traveler's need to understand the self, as the programs’ personality clashes and emotional breakdowns move front and center. The past, meanwhile, is reconstructed as a decorative backdrop and the “life lessons” gleaned from the video confessionals all tell a similar tale. The teenaged Tracy Clune of Frontier House, for example, predicts that when she returns to her twenty-first-century life, she will be less materialistic, and hence a “better” person: “I'm not the same person, and I'm happy about that” (www.pbs.org/wnet/frontierhouse/families/profile_tracy.xhtml).

As the participants in these experiments typically conclude, the point of all their “suffering” (e.g., doing without shampoo or processed foods) is to understand and question their current lives and values, while realizing that the past and present are not so different after all. The penniless singer in Regency House Party, Mr. Carrington, explains how the experience “opened my eyes to a world I knew little about, which changes your perspective on the modern world we live in.” Not surprisingly, historians criticize such a superficial approach to learning history, in which issues of class, race, and gender inequality, which clearly mark the past as different and distinct, are glossed over. But even Hunt acknowledges that the same analytical rigor that is demanded of the published historical text does not always make for a “lucrative media commodity” (843). Furthermore, to call reality history TV “bogus history” or “trash” misses the point of these programs and of the volunteer's and viewer's personal relationship to history (Nelson 143). In her study of the mythology of the American West, Liza Nicholas observes that “what people believe to be true about their pasts is usually more important in determining their behavior and responses than truth itself” (xvii). It is through these myths, she adds, that we make sense of ourselves and explore our identity. Even Hoppe admits that her childhood memories of the Little House books and TV series based on them prompted her desire to revisit the pioneering experience in Frontier House and to see if twenty-first-century citizens could measure up to the Ingalls family.

As soon as the viewers meet the volunteers on the House programs, it becomes clear that the “living history” experience is dependent less on the advice of historical consultants and more on fictional depictions (and collective memories of such depictions) of the various pasts that the House programs aim to faithfully re-create. Since the “total” experience cannot possibly be re-created (no one dies from TB, dropped bombs, or malnutrition in these shows), we are ultimately left with more fiction than fact, and the myths that Hoppe says the series aim to “bust” often remain intact. Watching an episode of Regency House Party or Texas Ranch House cannot help calling to mind certain familiar novels, films, and earlier TV programs that tried to capture these same eras. And the performances of those who take part in these time-traveling experiments are shaped (both unconsciously and at times deliberately) by such fictions, such as the housewife coping with rations in 1940s House who imagines herself in “my Mrs. Miniver mode,” Manor House’s tutor and his Jane Eyre fantasy, and the girls on the frontier who clearly want to emulate the gumption of the Ingalls daughters. Even as the volunteers gain a general familiarity with a particular era and its hardships, they remain reluctant to let go of certain notions about the past. In the words of Regency House Party's Captain Glover, what they really want is “a romantic experience as well as a historical one.”

Media critics, quick to distinguish the House series from the “worthless trash” of other reality TV fare, typically refer to it as the “Masterpiece Theatre” of the genre, further collapsing the boundary between history and fiction.3 Each series follows a set formula in which the applicants are introduced and begin their preparation for their impending ordeal; volunteers who generate the most drama (whether in the form of a love story, a feud, or a revolt against the rules) stand out, and video camera “confessionals” and postseries interviews highlight the conflict between the volunteers’ historical role-playing and their twenty-first-century lives. There are no prizes for enduring a harsh winter or emptying chamber pots, although the American productions grade the volunteers. This grading system at first seems to undermine the community spirit so essential to the volunteers’ survival but also forces them to question their own modern notions of individualism, competition, and self-interest.

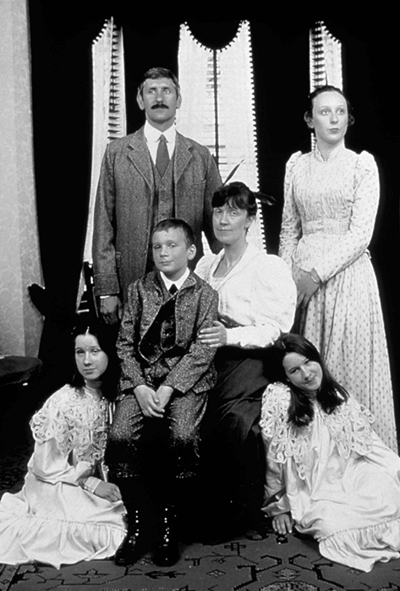

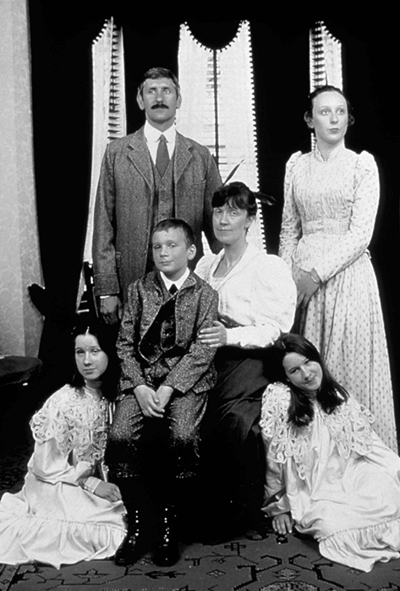

The Bowler family of The 1900 House (PBS, 2000) pose in their Sunday best. Courtesy of PBS/PhotoFest.

The total immersion process and length of time the volunteers are required to spend in their historical contexts, ranging from three to five months, make for grueling, and ratings-savvy, “hands-on history.” In these televised experiments, the volunteers have to struggle for their subsistence, submit to authority, rely on outdated medical remedies, and abandon their modern dress for uncomfortable, often dirty period costuming. Despite these inconveniences, the volunteers are surprised by the ease with which they take up their assigned roles—the submissive lady's maid, the class-conscious butler, the domineering husband, the lowly ranch hand. Yet the volunteers never fully become their roles; they adapt their historical identities to their twenty-first-century mentalities and experiences when, for example, the servants of Manor House mouth off to their master or the colonists in Colonial House refuse to cheat their Native American trading partners. Much to the producers’ dismay (or perhaps glee), the volunteers rewrite the past as they wish it had been, sans socioeconomic hierarchies and prejudice.

Although the producers claim that they do not generate the story lines or prompt the participants to react in particular ways to various situations, they do predict that the experiments will challenge the volunteers’ preexisting assumptions about the past.4 But just what are those assumptions and where do they originate? Ian Roberts in his audition video for Texas Ranch House declares he had been prepared to play a cowboy since childhood, having “watched a lot of Bonanza growing up.” Many years later, he now longs to lie out “under the stars by the fire and ride a horse in the rain…. This is a chance to show America that we lost values, we lost beliefs, we lost integrity.” Like many of the House volunteers, he idealizes the past, but his main source of knowledge is reruns of a 1960s TV series. Audition videos typically show applicants expressing a fascination with the time period under investigation, but the selected few usually arrive on the set with very little background knowledge other than what they are given by the producers. In an interview Lady Olliff-Cooper of Manor House reveals that the producers “discouraged us from reading up about it…. The rule book was very slender and only gave you the barest outline of where you were supposed to be.”5 Mr. Edgar, the butler, adds, “Although I'd read a lot about servants and the role of the butler, I said I could do with some training from a real butler. I was extremely lucky and had training for four days from the adviser to Gosford Park, and that was wonderful because lots of little details I may have overlooked, he made me aware. Apart from that, we weren't encouraged to know very much.”6 Their responses to their new environment, therefore, are dictated not only by their twenty-first-century attitudes and values but also by how they imagine characters from film and TV would behave in similar situations. “But at the end of the day,” as Mr. Edgar shrewdly observes, “the producers must have been jolly glad.”7

Britain's Channel 4 clearly found a winning formula with its 1999 production of 1900 House. The House series that have followed have become much more sophisticated and interactive, and thousands of applicants have vied to relive suburban life during World War II or serve as a butler for an aristocratic Edwardian family. With 1900 House the producers seemed determined to convince the media and viewers of the project's seriousness—advertising the program as a documentary and offering lesson plans for teachers on its Web site. By 2002 Manor House was being promoted as “a gripping new series that brings class to reality television.” Even its accompanying Web site had abandoned pretensions to historical seriousness, offering viewers a “Snob-o-meter” to test “just how snobbish you are,” and applicants who admitted to fantasies of “shagging the scullery maid” received the most airtime. Surprisingly, more than 80 percent of the applicants to Manor House wanted to work as servants, and those quoted were motivated by the popular television series Upstairs, Downstairs (1971). Promotional advertising for the series even referred to Manor House as “in the tradition of Upstairs, Downstairs and Robert Altman's Gosford Park,” stressing its similarity to other popular, fictional fare rather than its putative resemblance to history.

Nevertheless, Manor House works hard at challenging the volunteers’ romanticized views of life on a country estate, as the camera focuses on the backbreaking labor performed below stairs and the shocking reminders to the servants that they must “know their place.” Yet when certain volunteers stay too true to their historical roles, it becomes difficult for modern viewers to empathize with them. For example, when Sir Olliff-Cooper defends the class structure and the empire, or exercises authority over his wife and spinster sister-in-law (who at one point abandons the house to avoid a real-life breakdown), he seems, by twenty-first-century standards, boorish and arrogant; in short, he has become his historical alter ego. In the final episode of Manor House, as the aristocrats upstairs dance and celebrate the British Empire, the staff below stairs read about such events as militant suffrage and trade union marches and the Titanic disaster—all of which hint at the impending death knell of the Edwardian age and its hierarchies. But the servants have already written their own ending to this age, since they have repeatedly refused to accept their lower position in the household; they have burned the master in effigy, romped in his sheets, swapped jobs, and become drunk while on duty. They simply refuse to “live history,” and their pride in their ability to endure three months of hard work and poor hygiene suggests how they have reduced history to a version of “today” minus its twenty-first-century amenities.

Since the Edwardian time-traveling experiment, set in a country house, proved a great success (reaching an audience of more than 3 million), Channel 4 used another rural venue two years later to re-create the early nineteenth century. The architectural historian Adrian Tinniswood points out the enduring significance of the country house for even twenty-first-century tourists and TV viewers—a part of the past “with as much to say about contemporary society as it has about what has gone before” (quoted in Troost 478). Evoking a nostalgia for the alleged simplicity of the preindustrial past, the country house conveys a physical and emotional space in which the stresses of modernity can be abandoned. But whereas Manor House made some effort to re-create a less romantic version of Upstairs, Downstairs and used the class and gender inequality of the Edwardian era to generate dramatic tension among its volunteers, Regency House Party shed any pretension to historical accuracy when it used as its leading historical consultant the novelist Jane Austen (1775-1817). In 2004 Channel 4 announced that it was offering a “marriage of reality dating programs with history by giving five aspiring Mr. Darcys and five Miss Bennets the chance to go back to the England of the early 1800s and live at the height of the age of romance.” When the show later aired on PBS, the theme song from the 1970s program The Dating Game played in the background, as American audiences (likely more familiar with this piece of TV history than with the British Regency era) were promised “the ultimate dating game.”

Again, the producers chose volunteers with self-admitted low history IQs. Guy Gorell Barnes, the master of the house, and a “Mr. Darcy look-alike,” was “excited about living in history,” but he noted, “We were given very little information about what to expect.” Likewise, Mr. Foxsmith, the amateur scientist in both his twenty-first- and nineteenth-century lives, admitted, “I had very little idea about the period. I've never read a Jane Austen book.” Even the London stage manager-turned-Regency gentleman, Mr. Everett, was “frustrated by my lack of knowledge…. I knew nothing about the period before I started the project.” Perhaps two of the better-prepared volunteers were one of the chaperones, Mrs. Hammond, who admitted to watching “a lot of Jane Austen videos,” and Miss Braund, who “had read all of Jane Austen's works and was very interested to find out how the reality matched my own romantic views.”

On the Regency House Party Web site, the producer Caroline Ross Pirie explains that when looking over 30,000 applicants, she was searching for “the modern day equivalents of the people who feature in Jane Austen's popular novels.” The selected guests are too good to be true—a retired female army officer turned romance novelist now in the role of chaperone; a former model and society debutante playing hostess of the party; an actual Russian countess (and waitress) in the role of a secretly impoverished noblewoman in pursuit of the host; a dot-com millionaire; and a disenchanted speed dater; the only one to quit the experiment in its early stages is the hairdresser, who expected his character, Captain Robinson, to be like Austen's militiaman Mr. Wickham—”gambling, womanising and drinking.” Instead, he realizes that lessons in walking and gentlemanly etiquette are not for him: “I don't want to be posh.” The experience, however, does make him “proud of my (working class) roots.”

Without a script, the only guidance the volunteers have is an individualized pocket book outlining the behavior expected of them. According to the narrator, it is up to the “guests” to decide “the extent to which they would conform to Regency protocol and etiquette.” Though historical consultants were used “on everything from Regency sanitary arrangements to popular card games,” the real go-to source remained fiction. Many of the episodes’ titles come from Austen's novels—”Pride & Prejudice,” “Sense & Sensibility,” and “Persuasion”—and the volunteers eagerly take to their new roles. There is a self-professed Fanny Price character—the penniless lady's companion Miss Martin (also referred to as the Cinderella of the party)—and a meddling Emma (Miss Hopkins, an “industrial heiress” who plays matchmaker but then steals her friend's chosen mate for herself). Abandoned by Mr. Everett in favor of the heiress, the impoverished Miss Braund resembles Sense and Sensibility’s Marianne Dashwood; after losing the attentions of young, handsome Mr. Everett, she is rescued in the final episode from spinsterhood by an engagement to her older friend, Captain Glover. Among the male volunteers, the tension between the youthful Wickhams and the older, steadier Captain Wentworths leads to comical displays of physical strength and even the padding of tights. The interactive Web site encourages further Austen fantasy role-playing for those who wish to “find out if you've got what it takes” to be a Mr. Darcy-like catch or one of the Bennet sisters.

The other literary reference that influences the party guests’ behavior is Lord Byron (1788-1824), and the episodes titled “She Walks in Beauty” and “Mad, Bad, Dangerous Liaisons” offer up the raciest (and most uncomfortable) moments of the series. For example, to capture the attention of Mr. Gorell Barnes, the countess “serves herself up” as the dinner's centerpiece. Covered only by strategically placed fruits and peacock feathers, she says she is paying homage to Byron's lover, Lady Caroline Lamb, and in the end does indeed win her man. (Interestingly, like Mr. Darcy, who initially found Elizabeth Bennet's face only “tolerable,” Gorell Barnes first remarks that the countess would be attractive “without her glasses.”) This particular moment, though it spices up the diner party, represents a missed opportunity to comment on the position of women in early nineteenth-century society. The female volunteers complain endlessly about having to rub their underarms with lemons (a Regency-style deodorant) or their inability to drink with “the guys,” but they never fully grasp how even upper-class women were disenfranchised in Regency England. Lamb's act was not only scandalous but earned her the reputation of being mentally unstable and almost ruined her husband's political career, and Byron shunned her for another woman. Byron, not Austen, is used whenever the volunteers want to break not only the dull routine of the day but the rigid gender conventions, but it is mainly the men who reap the benefits. Conveniently discovering that his cellar once housed a meeting place of Byron's Hell Fire Club, Barnes invites his male guests and several exotic female dancers to an after-hours party, which prompts Captain Glover to exclaim, “Jane Austen, it ain't!”

Aside from these moments that scandalize the elderly hostess of the party, most of the romantic intrigue remains tame—daisy chains, serenades, and love mazes. In addition to dating rituals, the volunteers learn about dueling, boxing, and dining etiquette; there are a few passing references to the slave trade and the class hierarchy that divides the servants and guests and allows the latter to be so pampered at the expense of others. An outsider is invited into the house to stir up controversy and expose some of the realities of the past that period novels often ignored. None of the House series can resist this type of moralizing, but such moments of historical accuracy are regarded as a nuisance by the volunteers, who want to sustain their fantasy of the past. According to the narrator, with the arrival of a West Indian heiress in episode 3, “the guests must confront the truth behind their lavish lifestyle.” Unfortunately, this plot device goes nowhere, and no romantic partner is provided for Miss Taylor, despite her millions and beauty (which the chaperones initially resent and the other young ladies envy). Miss Taylor, does, however, get a chance to lecture the group about the wealth of landowners reaped from the slave trade of the preceding two hundred years. Still, an attempt to stage a boycott of sugar for just one day is met with resistance—as the underprivileged lady's companion Miss Martin says, “I just can't feel guilt or shame for something I've never done…. I can't feel guilty for history.” Miss Martin's response is a rare example of being “true” to the historical era under examination, but she is shushed and Barnes mandates the daylong sugar boycott.

After this brief lecture on slavery, the series returns to its main theme: romance. The houseguests cannot seem to stop themselves from straying from their nineteenth-century roles, as an unchaperoned Miss Martin repeatedly visits the estate hermit, and the chaperone Mrs. Davenport, rather than promoting her female charge, falls in love with the younger Mr. Foxsmith. Whenever they are shown together, sepia tones are used—comparing this “indiscreet” relationship to Byron's penchant for older women. Alas, aside from a midnight meeting in the stables, their love is not meant to be, as she finally reverts to her historical identity and insists that he be free to marry a younger woman of fortune. Mr. Foxsmith finds solace in his scientific experiments, and part of episode 3 pays homage to Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818) as the guests discover electricity and meet an anatomist.

The gothic, yet another literary creation of the Regency era, dominates the second episode, as the guests write and perform their own ghost story, and lovers hunt for phantom spirits at midnight. The often forced nature of the drama is most evident when a “violent row” between Miss Braund and her chaperone erupts (physical blows allegedly were exchanged off camera). The camera flashes to a full moon and a bat flying across the window, and a beating drum and shouting voices signal that “the house party is in crisis.” Any pretension to a history lesson is abandoned for this costumed and carefully edited catfight.

Watching such drama unfold and listening to the narrator, TV audiences might reasonably assume that the Regency era really was nothing more than romance, poets, and ghost chasing. (To be fair, the Channel 4 Web site does offer a brief history for “those still a bit in the dark about the Regency period.”) Politics can no longer be ignored, however, and in the final episode, a discussion of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) occurs. The guests receive a history lesson on the Battle of Waterloo of 1815 (though, as previously noted, the guest historian's words are drowned out by music), and Captain Glover, who would have served in the navy, receives a fortune and a title as a reward for his heroism. Though the oldest of the male guests, and previously trying, and failing, to catch the ladies’ attention with his workouts and padded tights, he now has become the most attractive man in the household, richer even than the host. Though he should court the countess, he chooses instead the middle-class Miss Braund, who decides “there's something to marrying a best friend.”

The final episode asks, “Will this storybook tale of mating and dating have a happy ending?” The wedding, by convention the culmination of the Regency novel, certainly would signify the success of this living-history experiment, and the impending nuptials of Miss Braund and Captain Glover follow this formula. Some of the houseguests, however, have written their own preferred ending. The lady's companion has run off with the hermit, and one of the guests, dismayed by her marital options, decides she will become a courtesan, with her own salon—two very un-Regency-like decisions. Furthermore, the countess and the host, after a drunken one-night stand, are declared by the narrator to be engaged, superimposing modern dating practices on Regency courtship rituals. So though the houseguests have had, in the words of Captain Glover, “a romantic experience,” did they have a “historical” one? Was the show's intention to learn about the period? To appeal to and create more Austen fans? As the historian Hunt notes, it is really about the volunteers getting to know themselves—not history—better. During a church service, an actual twenty-first-century clergyman explains to the cast that they are enduring the inconveniences of primitive hygiene and rigid etiquette “out of a desire to find a new way of looking at relationships.” Yet again, the study of history—the supposed aim of these “hands-on history” projects—becomes secondary to exploring contemporary individual identity. Captain Glover honestly addresses the serious omissions of history when he wonders, “Would I have been suited to the Regency House War? The Regency House Amputation? The Regency House Wife Death in Childbirth? … I would need a real time machine to answer the question truthfully.”

The urge to treat history as a story, with plot lines easily rewritten to suit the time traveler's own contemporary code of ethics and sensibilities, can also be seen in such American versions of historical reality TV as Frontier House, Colonial House,8 and, most recently, Texas Ranch House, all on PBS. As the Texas Ranch House Web site promises, this “latest and most ambitious experiment in living history” explores “what the saddle-sore, rope-burned, and sun-blistered ranch life was really like.” But, though the producers promise to “bust some myths,” they carefully edit the several weeks’ worth of collective experiences, showcasing the confrontations as the volunteers rebel against the strict rules and hierarchies of the ranch; swaggering in their chaps and boots, they cling to their own fantasy of the cowboy life.

Myths about the Old West have captivated generations of Americans, who, according to the historian Frederick Jackson Turner, view the frontier as the site where American democratic ideals were fulfilled.9 In less than one hundred years the American West was settled, native tribes were vanquished, and railroads stretched across the prairies and mountains; cattle drives romanticized the cowboy, and telegraph and telephone lines linked the Eastern Seaboard with California and tales of golden sunsets. Popular culture has enshrined the frontier through literature, paintings,Wild West shows, radio and television, and Hollywood films from The Great Train Robbery (1903) to the most recent “old-fashioned modern western,” 3:10 to Yuma (2007).10 Clearly, the American West continues to exert a powerful attraction for twenty-first-century audiences still rooting for heroes with “true grit.”

Hollywood westerns, on film and TV, according to the film historian Peter C. Rollins, have created “an American culture … almost unimaginable without the West as a touchstone of national identity” (2). Even the environment plays a part, as western landscapes have helped shape this mythology; as Deborah Carmichael has observed: “The importance of the landscape itself, the idyllic or treacherous environment negotiated in these films, often receives supporting-role status, yet without the land, American national mythmaking would not exist” (1). Jared Ficklin, a native of Austin, a Texas Ranch House cowboy, and a descendant of Benjamin Ficklin, cofounder of the Pony Express, agrees, wanting only to become a “true Texan” worthy of his famous ancestor.11

Unlike the Hollywood westerns by directors Howard Hawks and John Ford, reality TV works with little scripting (though much postproduction editing), and as one TV critic notes of Texas Ranch House, “what seems familiar from movies and TV takes on fresh significance when there are real people—not pampered actors—trying to scratch out an existence on the frontier 24/7, with no plot to guide them.”12 Though the producers of PBS's Texas Ranch House adhere to this no-script approach to their living-history experiment, the Hollywood myth of the Wild West nevertheless shapes the participants’ actions. In fact, many of the interactions between the Texas Ranch House volunteers seem lifted from classic westerns, in particular Hawks's Red River (1948). Red River is a tightly woven story about a hardened cattle baron, Tom Dunston (John Wayne), and the younger, gentler Matt Garth (Montgomery Clift), who, despite their own personal animosities, succeed in building a cattle empire in post-Civil War Texas. The film's familiar themes of an epic quest, male bonding, and strong-willed women are all found in Texas Ranch House. Still, the volunteers manage to challenge not only the advice of historical consultants but also certain aspects of the Hollywood myth to produce their own version of a western, modified by a collision with modern values.

Among the 10,000 applicants to the show, the few selected include two Californians, Bill and Lisa Cooke, as the ranch owners (along with their three daughters—all Little House on the Prairie buffs); a self-proclaimed feminist, Maura Finkelstein, in the role of “girl of all work”; and a motley group of ten male cowboys, including a gruff, short-tempered ranch foreman, the Colonel, and a temperamental ranch cook, Nacho. After a two-week “cowboy skills camp” conducted by historians of the period, the volunteers find themselves settled on a private cattle ranch in the rugged Chihuahuan Desert located thirty miles south of Alpine, Texas, re-creating ranching life circa 1867.13 The daunting task for these time travelers is to round up two hundred longhorn cattle and sell them in order to save the Cookes’ ranch from financial disaster. In post-Civil War Texas, hundreds of thousands of longhorn cattle roamed the Texas prairie, abandoned by their previous owners, who had left to serve in the Confederate Army. This challenge clearly falls within the scope of the historical record, and it also parallels the story of John Wayne's character, Tom Dunston, in Red River. The shadow of Wayne, Hollywood's iconic cowboy, looms over the entire TV production, setting a standard of Western masculinity for the volunteers and audience, who are urged on the program's accompanying interactive Web site to “Test Your True Grit” and “Speak Cowboy.”

According to series producer, Jody Sheff, “Texas Ranch House may be the most challenging hands-on history series we've done. The ranchers and cowboys are constantly working with temperamental horses, riding a harsh terrain riddled with ravines and rattlesnakes, not to mention the 100-plus-degree heat. The physical demands on our participants and the distances they must cover make the House experience unique.”14 But as one of the cowboys remarked in a WashingtonPost.com interview, “the drama aspect of it drained me more than the actual ranch work.”15 The paucity of historical knowledge that the volunteers are given before their adventure begins contributes to the feuds that later ensue, as most of them refuse to stay in character when their modern values (and notions of comfort) are challenged. The volunteers may have learned how to rustle cattle, but the camera seems more interested in capturing the clash of personalities. In fact, as the ranch owner's wife, Lisa Cooke, notes in a postseries interview, the producers clearly had their own agenda, which was at odds with the goal of “living history”: “As participants we were told very clearly that we were to be 21st century people living in an 1867 environment.”16 This certainly explains the cowboys’ lack of deference and the outright acrimony and distrust between them and the Cookes. In the opening montage the cowboys view the arrival of their employer and his family with disdain, as one proudly declares that “first to be a cowboy, you need a set of balls!” The men will use said balls not only to endure the hard work that awaits them but to defy repeatedly the ranch owner for whom they already have little respect. (Cooke did admit in his audition video, after all, that he likes to pick berries for his wife's jams.)

But the challenge to Cooke's patriarchal authority will come not just from his cowboys but from those in his own home. Just as Dunston's fiancee in Red River warns him, “You'll need me for what you've got to do,” the female volunteers in Texas Ranch House refuse to let the experiment be what one Cooke daughter calls a “sexist ranch house.” Maura Finkelstein, the “girl of all work,” adds that she should be rounding up cattle instead of playing the Cookes’ domestic servant. Posing a “Calamity Jane” threat to a historically masculine enterprise, she cannot help being disappointed, noting: “I was very angry. I actually thought that I might have the possibility of starting out as a cowboy and not necessarily the maid, so it was a disappointment at first…. As a woman, I felt very conflicted. I had no problem doing the work, but through the labor I performed I was treated differently. I balked when I found an organic sexism growing out from the division of labor.”17 The series’ producers jump at such opportunities to create a divisive atmosphere, which quickly places the time travelers into oppositional groups.

Indeed, most of the drama of Texas Ranch House derives from the “gender battles” (this phrase streams across the series’ Web site) as the female volunteers try to re-landscape the Wild West into an egalitarian terrain. Though women's role in the Hollywood western has always been that of being a civilizing influence, the female volunteers on the show do not seem to understand that “civilized” in 1867 actually meant maintaining separate and gendered spheres and creating a “home, sweet home.” Several of the young cowboys start the experiment “dreaming about … young ladies” with whom they might flirt, but instead encounter a “middle-aged … wife and a couple of kids” and a defiant servant. As the men resist the women's efforts to invade a traditionally hypermasculine world, Finkelstein shakes her head in disgust, remarking: “What's so interesting is that all of the guys come from different places and different experiences and they all, inherently, are sexist bastards, every single one of them. And they all love it. And they embrace it. And it took them five minutes to put on that jacket.”18 But veering from the role of “sexist bastard” would violate history as well as the script of the western and would not earn respect for the man who does so, especially when that man is the ranch owner.

Lisa and Bill Cooke modify their assigned historical roles as Lisa demands to be her husband's partner in the ranching enterprise, just as she claims she is his equal in their twenty-first-century home. Refusing to act the part of a submissive wife, she declares: “You men don't comprehend how much you hurt women on this ranch. And you hurt them in a way that as 21st century men you would never do in your regular lives. I'm raising three daughters. I'm not raising them to feel pathetic about themselves.” Clearly miscast in the role of ranch owner, Bill Cooke loses any semblance of authority when he attends to domestic chores and puts family harmony before the success of the ranch and the cattle drive.

Curiously, though Lisa Cooke demands equal treatment for her daughters and herself, she has no qualms about denigrating the foreman's top hand, Robby Cabezuela, a modern day vaquero of Mexican and Spanish ancestry who seems much better equipped for the role of ranch owner than Bill Cooke. Lisa's treatment of Cabezuela, bordering on racist, is at least true to the historical moment under examination, but it makes for uncomfortable viewing nonetheless. Unlike the peacemaker in Red River, Tess Millay, who urges the warring men to love each other, Lisa exaggerates every slight toward her husband and family, accusing Cabezuela of being “disrespectful from the beginning.”

As a respite from the “gender battles” that crowd the action, the producers introduce another classic feature of the western, the “cowboy versus Indian” plot line. Looking for cattle, Jared Ficklin and Robby Cabezuela “unexpectedly” (i.e., they are not forewarned by the producers) encounter a Comanche raiding party, led by a Native American, Michael Burgess, in the role of Chief. Tense talk ensues as they debate the Comanches’ need for cattle and the ranch's need for fresh horses. The Comanches decide to hold Jared overnight so that he can be used as leverage, and they advise the men that in different times they would have been killed on sight. The next morning the Comanche's Chief rides into the Cooke compound to discuss the trade with an agitated Bill Cooke. When the Chief demands forty head of cattle in exchange for four horses and the hostage, Cooke initially refuses, stating that “he doesn't deal with terrorists,” until he is gently reminded that the Cooke ranch is on Comanche land and exists only at their whim. A humorous and truly twenty-first-century moment follows when the Chief thanks the Cooke women for the meal they have prepared and asks if he may take some of the food in a to-go bag. At the conclusion of this episode, Jared Ficklin is seen playing an Indian flute, seemingly at ease with his captors after just an overnight stay.

This episode is an interesting reversal of the typical captivity narrative, in which the hostage is usually a female who, in such Hollywood versions as The Searchers (1956), resists rescue. This entire episode points out the dilemma for these time travelers who want to relive the Old West but not repeat its racist practices, using anachronistic words like “terrorists” to describe the Native Americans rather than that classic slur used by Hollywood heroes: “dirty Injuns.” That the Chief is the most rational and gracious—putting Cooke in an even worse light—also undermines the western's dichotomy of civilized-savage. Since this is not a Hollywood western, or a truly faithful reliving of history, there are no violent confrontations between the two groups of men. Jody Sheff suggests that guns were not allowed on the set because of “insurance reasons,” but it is also possible that no twenty-first-century man, regardless of his John Wayne fantasy, wants to be cast in the unsympathetic role of “Indian killer” as millions of PBS viewers watch.

Fraught with tensions (albeit mainly harmless ones) between the men and women, and between the cowboys and Indians, Texas Ranch House, like all westerns, is ultimately a battle of man versus man. The climactic moment occurs during the cattle drive and Bill Cooke's final showdown with his cowboys. Emboldened by his success in selling his cattle and encouraged by Lisa, Bill is now ready to redress the outrages he believes the cowboys have inflicted on his family. Bill's desire for revenge brings to mind Red River and the ongoing conflict between Dunston and Matt. When he refuses to honor Jared's purchase of a horse before the cattle drive, accusing him of cheating him during his stay with the Comanches, Jared rises to this challenge, announcing his intention of riding out with “his” horse. With Lisa, the Cooke girls, and Maura Finkelstein all intently listening from the safety of the ranch house, Bill Cooke shouts that he will “kick the shit” out of Jared if he leaves with Cooke's horse. This threat notwithstanding, Jared rides away, followed by the other cowboys, heading off into the sunset. Asserting their independence (and defying the ultimate authority of the ranch owner), the cowboys have written their own twenty-first-century ending to the western. The historians’ final pronouncement, that the Cooke ranch, by nineteenth-century standards, would surely have failed in the face of such poor management and rebellion by the cowboys, does not seem to daunt any of the volunteers. The postproduction confessionals all attest to the volunteers’ “giving it their best”—blaming each other for the ranch's failure—which for modern audiences, but not historians, is good enough.

The English manor's drawing room of Regency House Party and the fly-infested dwellings of Texas Ranch House seem worlds apart, but viewed together, the two House series highlight the strengths and weaknesses of the genre of historical reality TV. PBS's producer Jody Sheff insists, “While of course we'd like to have as many people watch the show as possible, our only priority is making a great educational show that is also entertaining—but the historical element is always the primary focus.”19 Audiences watching the volunteers struggle with their unfamiliar environments and with each other get a glimpse of how challenging it is to make the past come alive and remain “authentic.” Tristram Hunt is undoubtedly correct, however, in questioning the latter part of Sheff's claim, noting that reality TV reduces the study of history to issues of individual identity and what moderns learn they can or cannot endure as they reenact the past.

The presentism of the nonhistorian producers and the participants undoubtedly shapes the outcome of the living-history experiment and leads to more melodrama than history. The volunteers, often and deliberately kept by producers in the dark about the period they are about to relive, cannot help being shocked when they realize they must passively submit to another's authority, empty someone else's chamber pot, or uphold the slave trade. That they measure their performances against those they have seen on TV, like the Cartwright brothers, or have read about in their favorite Austen and Ingalls Wilder novels, reveals just how difficult it is for the volunteers to distinguish fiction from history. When they break the rules, as they inevitably do, the volunteers imagine they will be rewarded, like Austen's outspoken heroines whose impoverished status never seems to deny them a favorable love match, or John Wayne's macho heroes who refuse to take orders from weak-willed men. Even though an occasional historian is shown shaking his or her head over the historical inaccuracies of the House series, the producers still allow the volunteers the freedom to write their own script. Meanwhile, the postproduction editing team transforms their three months of interactions into a miniseries with love triangles, feuds, and background music, furthering the fiction behind the stated objectives of the living-history project itself. Perhaps a more accurate description of the appeal and the limits of historical reality TV is expressed by Regency House Party’s countess, who concludes that such programs keep alive the fiction that history was simply “a storybook every day.”

1. Description of 1900 House, “About the Series,” www.pbs.org/wnet/ 1900house/about-series/index.xhtml.

2. Beth Hoppe quoted in Dan Odenwald, “Back to These Old Houses,” Current, April 21, 2003, www.current.org/hi/hi0308house.xhtml.

3. Mark D. Johnson, “The ‘Masterpiece Theatre’ of Reality TV” (review of Manor House), www.partialobserver.com/article.cfm?id=718.

4. Hoppe in Odenwald.

5. See http://discuss./wp-srv/zforum/03/sp_tv_ manor042903.htm.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. For a discussion of Colonial House and Frontier House, see Julie Taddeo and Ken Dvorak, “The Historical House Series: Where Historical Reality Meets Reel Reality,” Film & History 37.1 (December 2007): 18-28.

9. Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History (New York: Dover), 1996 [1920].

10. See www.filmsite.org/grea.xhtml and www.imdb.com/title/tt03881849/.

11. “Texas Ranch House,” online interviews of cast members conducted by WashingtonPost.com, May 1, 2006. No longer available on the Washington Post's Web site; hard copy in authors’ possession.

12. Nancy DeWolf Smith, “The West That Never Was,” Wall Street Journal Online, April 28, 2006, http://online.wsj.com/public/article_print/ SB114618251554138180.xhtml.

13. Texas Ranch House press release, www.thirteen.org/pressroom/pdf/ texas/TexasRanchOnline.pdf.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. “Texas Ranch House,” online interviews, WashingtonPost.com.

17. WashingtonPost.com, April 4, 2006. No longer available on the Washington Post’s Web site; hard copy in authors’ possession.

18. Texas Ranch House press release.

19. See http://pbs.org/texasranchhouse.

Carmichael, Deborah. The Landscape of Hollywood Westerns: Ecocriticism in an American Film Genre. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2006.

De Groot, Jerome. “Empathy and Enfranchisement: Popular Histories.” Rethinking History 10.3 (September 2006): 391-413.

Hunt, Tristram. “Reality, Identity and Empathy: The Changing Face of Social History Television.” Journal of Social History 39.3 (Spring 2006): 843-858.

Nelson, Michael. “It May Be History, but Is It True? The Imperial War Museum Conference.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television 25.1 (March 2005): 141-146.

Nicholas, Liza J. Becoming Western: Stories of Culture and Identity in the Cowboy State. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

Rollins, Peter C., and John E. O'Connor, eds. Hollywood's West: The American Frontier in Film, Television, and History. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2005.

Troost, Linda V. “Filming Tourism, Portraying Pemberley.” Eighteenth-Century Fiction 18.4 (Summer 2006): 477-498.