EIGHT OSCARS, SEVEN BAFTAS, FIVE Critics’ Choice awards, and four Golden Globes: Slumdog Millionaire’s (2008) landslide victory in just about every international film award competition seems to echo a lesson from the year’s triumphant Obama playbook: yes, Jamal can; yes, India can; yes, even Bollywood can. Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire pays powerful hommage to popular Hindi cinema of the 1970s when that cinema was beginning to be named Bollywood. The first question Jamal is asked on the quiz show is the name of the actor who starred in the 1973 blockbuster, Zanjeer (Chains, Prakash Mehra). Jamal knows the answer, of course, just like most Indians would, regardless of their class or social status. Yet the real question is not who played the angry young man in Zanjeer, but why that figure continues to be relevant in the India of the 1990s and beyond, which is when Jamal, probably about six or seven years old, dives through a sewage pit to get Amitabh Bachchan’s autograph when the screen god descends from the firmament in a helicopter. Jamal’s devotion to a screen idol well past his prime is of a piece with the ecstatic, excessive response that certain blockbusters from Bombay enjoy, not just among slum dwellers like Jamal, but among viewers across many parts of the globe where Bachchan and Raj Kapoor and Nargis and Shah Rukh Khan among other Bollywood superstars elicit similarly frenzied adulation long after their blockbusters are decades old.1

Fans of Bombay films could multiply these anecdotes manifold for virtually every nation on the globe with one major exception: the United States. The popularity of Bombay’s blockbusters provide invaluable insights into the travels of a truly mass culture in having taught Nigerian youth to weep for Nargis, Egyptian traditionalists to yearn for Dimple Kapadia, and Greek workers to hum Mukesh numbers in Hindi.2 Yet their influence upon audiences in the United States has been hard to detect and even harder to ascertain. If Bombay films have a global centripetal flow, it appears to have stopped prior to reaching U.S. shores where these films exist far below the mainstream cultural radar. Until recently, occasional mainstream multiplexes in the United States might screen Hindi films for diasporic audiences on sporadic schedules advertised online or in the ethnic press, so the idea that Amélie might routinely share a screen with A Wednesday (Neeraj Pandey, 2008), or Run Lola Run might play alongside Rang de Basanti (Color it saffron, Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra, 2006) seems unfathomable to most filmgoers in this country.

Slumdog Millionaire’s massive critical and commercial success seems to have transformed Bollywood’s cultural invisibility in the United States to the extent that it invites a broader question: might the film’s many Bollywood flourishes and its layered references to that cinema finally augur Bollywood’s fuller penetration into the U.S. market that showered Slumdog Millionaire with such fulsome encomia? Slumdog’s remarkable journey from a small-budget film released in ten prints in U.S. art house theaters to one with almost 3,000 prints circulating widely in the U.S. suburban multiplex circuit makes some ask if it might have created a wider appetite for the film’s “ancestors” from Bollywood.3 Some film watchers insist that Bollywood’s presence in the Western mainstream is widely evident in the new millennium, a phenomenon that a group of scholars recently dubbed “Bollyworld.”4 Even before Slumdog Millionaire, Baz Luhrmann’s musical hit, Moulin Rouge (2001), had primed the Western market for things considered “Bollywood,” followed by Lagaan (Tax, Aamir Khan, 2001), the anticolonial cricket saga that was nominated for a foreign film Oscar in 2002. The same year, spectacular Bombay productions such as Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham (Sometimes happy, sometimes sad, aka K3G, Karan Johar, 2001) crossed the Atlantic and did exceptionally well at the U.S. box office. Meanwhile, Monsoon Wedding (Mira Nair, 2001), produced in the U.S., pilfered aspects of the Bombay industry’s formula, sterilized it, peopled it with Delhi’s consumerist elites, and purveyed the confection with hitherto unimaginable success to multiplex audiences in the United States.5 Monsoon Wedding remains the top-grossing Indian film in the U.S. at receipts of almost $14 million, with another Bollywood knockoff, Gurinder Chadha’s Bride and Prejudice (2004), at second place with receipts at $6.6 million.6

This brief profile of Bollywood’s travels to the United States underscores several details. The already unstable term from the 1970s has today mutated to incorporate any Indian-themed product, regardless of its site of production, distribution, or content. Thus, K3G (produced in India), Monsoon Wedding (produced in the U.S.), and Bride and Prejudice (produced in the UK) seem equally included in the vexed term, along with a film such as Slumdog Millionaire. As the film scholar Madhava Prasad poses: “could Bollywood be a name for this new cinema coming from Bombay, but also lately from London and Canada?”7 Despite superficial similarities in theme and setting across the cinemas, there is much that separates the productions even when they are all dubbed “Bollywood.” Slumdog’s insistence on conjuring 1970s blockbusters such as Zanjeer in order to comment sharply on an incredible India that frames slums alongside high-rises, criminals alongside pacifists, global industry alongside postindustrial squalor, often within a single shot, is nowhere visible in either Johar’s Bombay-produced K3G or Nair’s New York version. The confrontation with social problems that defined Bollywood’s identity in the 1970s seems to have retreated in products such as K3G and Monsoon Wedding with their exuberant embrace of the culture of consumer capital. Yet these are some of the very films that have recently crossed over to a U.S. market that has long been indifferent to Bollywood. This chapter analyzes why. It studies two linked phenomenon associated with the term Bollywood. First, it analyzes the mutation of substance from its origins in the 1970s that accompanies the term Bollywood today. Second, at a time when India’s media ecology has dramatically expanded, and popular film competes with modes of entertainment and media unknown and unimagined in the 1970s, Bollywood has had to make compromises.

This chapter analyzes what Bollywood does to survive both in India and in global markets that now include the United States. It addresses the question of Bombay cinema’s penetration into the U.S. mainstream. It proceeds concentrically in three parts: first, it addresses why this cinema works when and where it does; second, it explores the influence that recent U.S. financial interests and industry practices are having over Bombay cinema’s hitherto informal business model; and finally, it examines the select forms in which Bombay cinema has recently traveled into Hollywood’s home turf and scrutinizes why.

The argument of the chapter turns closely on this last point. In many ways, the germane issue is not the influx of Bombay cinema en masse into America’s screens but rather the specific forms from Bombay that have been able to capture the interest of audiences in the United States. This form is such a major departure from the internal conventions of Bollywood that it is more properly understood in a concept I define as Bollylite. Bollylite is a relatively recent fabrication that heavily pillages formal characteristics from Bollywood cinema while shearing much of that cinema’s social substance and political edge. Thus lightened, Bollylite travels, though, in contrast to Bollywood, with a remarkably limited commercial and critical half-life. Observing Bollylite’s fortunes and the material conditions that produce it allows one to observe the stubbornness of Bollywood’s cultural product despite the onslaught of a renewed global machinery with new capital. At a time when increased despondency has accrued in many quarters at the apparent demise of popular culture, Bollywood’s persistence as a form tells a very different story that shifts the locus of cultural study from the United States to a place where popular and mass culture have managed to coexist and even be the same thing.

THE WORLD ACCORDING TO BOLLYWOOD

Used both pejoratively and with pride, the term Bollywood has many faces and phases. It was initially used in 1976 to dismiss a cinema regarded as frivolous, spectacular, and escapist at a moment when the cinema’s social purpose closely engaged with the public and political culture of its time. Today, the term Bollywood captures not just these engagements but also a culture industry that has become international in production and global in consumption. It conveys as much a kind of cinema as a kind of response to cinema, the extravagant spectacle of its productions being matched by the outsize popularity that its blockbusters enjoy. Thus, to use the term Bollywood is to convey the cinema of Bombay that is also a cinema of excess in all its forms.8 In the usage I prefer, Bollywood is a heuristic device: neither epochal nor Bombay cinema tout court, it is a clarifying term to refer to a popular cinema made in Bombay that has claimed a social purpose and enjoyed a certain kind of popularity that it has maintained across time and audiences. Bollywood does not necessarily convey a national cinema, though Bollywood’s nationalist imaginary is an important component of its success both in India and overseas.9 In contrast to scholars such as Sangita Gopal, who remain sensitive to Bollywood’s origins in the 1970s but insist that the period of its global ambitions in the 1990s is constitutively different (Gopal calls it the “New Bollywood”), the present study demurs. Bollywood is a tendency that had its clearest expression in the 1970s when the term emerged. Retrospectively, with caution, it might be applied to an earlier period, and it certainly persists into the decades following its origins when it continues its social purpose in different forms.

In her exposition of Bollywood’s history, Sangita Gopal describes the period from Independence to the 1970s as the classic phase of Hindi cinema, characterized by what she calls a “socially responsive” national cinema (Gopal 2011:5). The events of the 1970s, Gopal contends, initiated a retreat from this project of national cohesion, and the cinema of “Bollywood” was born with a commitment toward mass entertainment. In this shift, according to Gopal, the social films that defined the classic period gave way to the masala films of Bollywood. Today, that entertainment- and commercially-savvy cinema of the 1970s has achieved new global ambitions in content and marketing, and Gopal characterizes it as the New Bollywood phase, which started around 1991 with the liberalization of the Indian economy. Gopal’s taxonomy associates each phase with a form (classic phase with the social film; Bollywood with the masala film; New Bollywood with genre films), and with a set of dominant preoccupations (social cohesion, violent individualism, and urbanization, respectively).

The schema glosses over a number of practices that remain consistent across the three phases. The first is the “master genre” of the social film that Gopal avers declined with the ascendance of masala in the mid- and late-1970s (Gopal 2011:14). To the contrary, rather than being a “genre,” the social film embodies a tendency of critique and response evident in virtually every phase of the cinema. As such, the social is more accurately a tendency that persists across all periods of Hindi cinema. It may be more or less prominent at a particular moment, but at no point have popular Hindi films ever abandoned the tendency. Similarly, the preoccupation with the nation suffuses the cinema at all moments. The kind of nation imagined in the 1950s differs from the one proffered in the 1970s or 1990s, but in each of its phases, Hindi popular cinema remains adamantly focused on the idea of a nation and actively engages in debating a variety of national fantasies. Exactly when the cinema is what Gopal calls “mere entertainment,” Bollywood most urgently exposes deeply held national fantasies (Gopal 2011:12). For instance, preoccupations with the national converge in the landmark masala blockbuster Amar Akbar Anthony (Manmohan Desai, 1977), which rewrites the trauma of Partition and the assassination of M. K. Gandhi as a manic reunification caper. However, these preoccupations are also prominent in a more sedately social film such as Mother India (Mehboob Khan, 1957), which reviews the same traumas, albeit with apologia as melodrama. The preoccupations over the idea of nation persist in kind if not degree across other forms, including vibrant indie films such as Kahaani (Story, Sujoy Ghosh, 2012) and Talaash (Search, Reema Kagti, 2012), both of which include A-list stars with mainstream credits. Therefore, to define the cinema’s historical phases by transhistorical tendencies such as the social is to reduce the industry to form at the expense of content.

Bollywood’s popularity among close to a billion viewers in the Subcontinent (and close to a billion more elsewhere in the world) explains partly why it has not succeeded (and perhaps not even tried to succeed) in penetrating Hollywood’s home turf. As a popular cinema deeply invested in the preoccupations of its domestic audience, it has traveled only as far as those preoccupations have. Mapping the success of Bollywood worldwide, one sees its appeal among a swathe of nations where modernity competes with tradition, where urban and rural commingle in uneasy proximity, where, as the scriptwriter Farrukh Dhondy perceptively noted, “underdevelopment meets development, where a peasantry and an urban population live side by side and are often the same people. It is that part of the world which lives through a clash of innocence and experience. . . . It is where the settled life of the village comes into contact with the temptation and even the routines of the city, the factory, the commodity, the market.”10 In these parts of the globe, audiences have flocked to Bollywood films as conveyers of a modernity that is neither American nor threatening to their fantasy of a “tradition” that they never quite had to begin with.

Where Hollywood mobilizes blockbusters to make money, Bollywood’s blockbusters have made the nation. The typical Bollywood film, if there is such a thing, is a perfect compromise solution to the conflicts of its time. Wreathed in spectacle, suffused in song, the public traumas of the day—be they Partition, dowry murders, class violence, or political corruption—are given shape and voice in dark movie halls. Like dreams that process in the subconscious that which cannot or should not be brought to the surface, Bollywood’s three-hour sessions in giant halls with names like Eros and Opera House address recurring fantasies that lie just below the surface. Bollywood exteriorizes and gives shape to the anxieties of its audience. It is a cinema that, to paraphrase the social theorist Ashis Nandy, is deeply invested in the psychic reality of its viewers, not its characters.11 Therefore, while Western audiences balk at the many elaborate dance sequences and the musical interludes that they frequently complain are “unrealistic,” for Bollywood’s Indian audiences these “unrealistic” sequences become occasions to sort through the dilemmas and conflicts presented in the plot without sacrificing pleasure.12

Raj Kapoor’s 1973 hit, Bobby, is as example of the cinema’s ability to have it both ways. Kapoor’s mastery over market and melodrama without compromising on either produced one of Hindi cinema’s most renowned blockbusters, which remains, at #6, among an elite group of all-time top-grossing Hindi films in the worldwide market adjusted for inflation, below Aditya Chopra’s Dilwale Dulhaniya le Jayenge (aka DDLJ, The man with the heart gets the bride, 1995, at #4) and Manmohan Desai’s multi-starrer, Amar Akbar Anthony (1977, at #5).13 Inspired by Kapoor’s reading of Archie comics, Bobby appears to be an endorsement of the impetuosity of adolescent love. Poring over an Archie comic, Raj Kapoor recalls, “I came across a sentence . . . spoken by Archie himself, something like, ‘Seventeen is no longer young—we have a life of our own too and we are aware of it!’ This really got me. I felt, here is something very profound—and thinking about this resulted in my making Bobby” (figs. 4.1 and 4.2).14

Instead of “Fast Times at Riverdale High,” Kapoor produced a cleverly refashioned account of his real-life courtship from the 1940s with the screen great Nargis (1929–1981), morphed onto concerns from the 1970s. Kapoor’s son, Rishi, plays Raja, scion of wealthy industrialist Nath and his neglectful socialite wife. Nargis, known as “Baby” in her lifetime, is reborn in the figure of Bobby, granddaughter of Raja’s Christian nanny, Mrs. Braganza.15 Smitten by the 16-year-old Bobby (played by Dimple Kapadia), whom he sees for the first time on his eighteenth birthday, Raja courts her with her father, Jack’s, consent. His own father is less welcoming, insisting that the family’s social status forbids Raja’s union with the nanny’s granddaughter. The duo prevail across Kashmiri landscapes and Goan beaches, fleeing an increasingly incensed set of fathers intent of separating their offspring to preserve their egos. Finally, with their fathers in hot pursuit, the couple decides that death together is better than life apart, and the two jump into some rapids. The fathers plunge in after them, each rescuing the other’s child, and the four, reconciled after the cold dip, walk off arm in arm down a yellow dirt road in a shot seemingly borrowed from The Wizard of Oz (fig. 4.3).

FIGURE 4.1 “To be honest, I am not a very well-read man.” Raj Kapoor with an Archie comic book.

(COURTESY SIDDHARTH KAK’S DOCUMENTARY, RAJ KAPOOR LIVES)

FIGURE 4.2 Publicity poster for Bobby (1973).

(AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

FIGURE 4.3 Bobby’s happy ending.

(COURTESY YASH RAJ FILMS)

On one level, the film’s conclusion and its lavish romantic staging celebrate the audacity of young love and its power over the forces of custom, family, and class. The lovers daringly act out throbbing pubescent desires during a school trip to Kashmir. “Imagine if we were locked in a room and the key got lost,” proposes Raja in a famous song, “Hum tum ek kamare mein band hon.” “I’d lose myself in the labyrinth of your eyes, and I’d come,” Bobby replies boldly, flinging herself onto the bed with arms open to receive her lover (fig. 4.4). Dimple Kapadia’s miniskirts, midriff-baring polka dot shirts, and her fabled red bikini were visual enticements of an audacious teenage sexuality hitherto unseen on Bombay’s screens (figs. 4.4–4.6). The song about being locked in a room together, with its sly lyrics and double entendres, sent viewers into paroxysms of glee at Kapoor’s naughtiness. Audiences love young love, apparently, and Kapoor was warmly recompensed at the box office for celebrating it.

FIGURES 4.4–4.6 Dimple Kapadia as Bobby.

(COURTESY YASH RAJ FILMS)

However, a closer reading of the songs in the film, especially the contrasting back-to-back numbers sung during a neighbor’s wedding, gives pause. Inspired by the wedding festivities, Raja promises Bobby his heart forever.

| Na chahun sona chandi | I don’t want gold or silver |

| na chahun heera moti | I don’t want diamonds or pearls |

| Ye mere kis kam ke? | What use are they to me? |

| Na mangun bangla bari, | I won’t ask for a bungalow or a house |

| Na mangun ghora gari— | I won’t ask for a horse or a car— |

| Yeh to hain bas nam ke. | These are just things after all. |

| Deti hai dil de, | If you want, give me your heart and |

| badle me dil le. [. . .] | take mine in exchange. [. . .] |

| Pyar mein sauda nahin. | There’s no trading in love. |

Without missing a beat, a second song, “Jhoot boley kauwa kaatey,” remarkably different in melody and mood, opens with Bobby threatening to leave for her mother’s if Raja doesn’t keep his vow. “Don’t you lie to me,” she trills, “or a crow will bite you, and besides if you lie, I’ll leave you and return to my mother’s house.” The remainder of the song is an exchange between the lovers, its exuberant dance and playful repartee barely able to contain the violence of the exchange. The fact that this song is staged as a spectacle performed at a wedding with the once miniskirted Bobby now costumed as a fisherwoman (fig. 4.7) goes quite some way in heightening the playful nature of the threats. Yet because the game is part of a public performance, the threats are more intense, the violence spelled out more menacingly. The visual attractions of the cinematic reds and blacks and blues of Bobby’s and Raja’s costumes play no small role in cuing the sinister colors of injury alongside those of pleasure (figs. 4.7 and 4.8). The hitherto independent Bobby is transformed in the second song’s (“Jhoot boley”) lyrics into a wretched victim of domestic violence, with the baby-faced Raja her tormentor in a marriage from which she has no escape.

RAJA: If you go to your mother’s, I’ll come after you with a stick.

BOBBY: You do that and I’ll jump into a well.

RAJA: I’ll get you with a rope.

BOBBY: I’ll climb up a tree.

RAJA: I’ll cut down the tree.

BOBBY [shocked]: Are you my suitor or an axe man? Beware of such lovers. Watch out or I’ll leave for my mother’s. Don’t you lie to me.

RAJA: Go ahead to your mother’s. I’ll get me another wife, you’ll see!

BOBBY: What? You’ll do that? [song shifts tone dramatically; Bobby prostrates herself at Raja’s feet; figs. 4.7 and 4.8] OK, I won’t go to my mother’s. I’ll serve you, I’ll be your obedient wife, I promise. I’ll observe all my marital vows. I won’t leave you, I promise.

RAJA [triumphant; dancing over the crumpled Bobby at his feet]: Don’t you lie, or a crow will bite you. And I’ll get me another wife, you’ll see.

Bobby’s freedom to choose a mate and her doting father’s support all end on her wedding when a lover can change into an axe man, and her only recourse from his abuse is the threat to return to a mother she does not actually have. While Bobby’s only power is her words, Raja’s is in brute actions. Unable to escape his stick, rope, or axe, she can only invoke her long-dead mother—or jump in a well to her death. Raja, on the other hand, always holds the upper hand, threatening her replacement with a second wife should she no longer please him.

FIGURES 4.7 AND 4.8 “I won’t leave you; I’ll observe my marital vows.” Rishi Kapoor and Dimple Kapadia in Bobby.

(COURTESY YASH RAJ FILMS)

The song’s subtext is even more sinister than its physical violence. In the decade before death by fire became the preferred method in dowry murders, “falling” into a well was the preferred way of eliminating a bride who had run her use as a source of dowry.16 Raja’s catalog of commodities he putatively declines in the first song (gold, house, car) rehearses a typical list of dowry demands. Raja and Bobby’s subsequent duet rehearses the preamble to a dowry death. Nothing, not even the threats, are innocent here. On any level, the sadism in the duet counters the utopian vow of true love in the first song, playing out the perils of adolescent love and serving as a cautionary tale of impulsive desire.

While the plot and staging of Kapoor’s blockbuster manifestly celebrate the theme of adolescent passion, the songs interrupt that continuity and latently correct an overt endorsement. The Raja-Bobby duet, “Jhoot boley,” cautions women in particular that leaving the family for a forbidden love is dangerous: love can turn and the woman, always vulnerable, has no recourse or support. Another narrative of social violence is marked behind Bobby’s frothy love story. The conclusion of the Raja-Bobby story re-creates the status quo of the capitalist male (Raja) claiming mastery over working-class labor (the fisherwoman Bobby) that remains typically female (figs. 4.7 and 4.8). That this ominous outcome is gestured in a song (“Jhoot boley”) in which the fashionably modern Bobby is dressed as a fisherwoman under scores that, romantic love notwithstanding, Bobby’s origins indicate her class’s destiny in a union with Raja.

Rather than the two songs appearing to contradict each other, they provide a sobering account of an “ever after” that the commercial film cannot manifestly provide. Bobby’s cinematic closure turns to Hollywood fairytale (the dreamwalk from Wizard of Oz; see fig. 4.3) not because it believes in fairytales. It turns there to point out the fairytale’s necessity against a violence that all fairytales both gesture toward and heroically contain. “They all lived happily ever after” is only comforting if one knows how unhappy ever after they might have been. Creating a space where the violent ever after can be enacted safely, in play, is caution enough. The point is to indicate a threat, not to eradicate it. What Bollywood’s audiences observe in these lyrical interruptions is the even-handed depiction of desire, rather than a contradiction inherent in its representation. This form of narrative irony, where manifest and latent content coexist without apparent disruption to the pleasures of spectacle, is exactly what recedes in later Bollylite productions with their singular narrative planes.

Recognizing the disruption of such narrative moments, Bollywood’s neglect in the United States lies less in American indifference to its stock formulae and musical numbers than in Bombay’s insistence on targeting the interests and preoccupations of its domestic audience. For Bollywood is first and always staunchly grounded in its origins in the Subcontinent. Its overseas success is a consequence of its popularity in India, not a compensation for the lack of it. Yet it deserves mention that a cinema that can contain deadly serious caution in spectacular frivolity as Raj Kapoor did in Bobby is a cinema with a special gift for transmogrification. As Farrukh Dhondy observes about Bollywood’s success outside India: “[Its films] carry abroad a nationalist message, but somehow that message is not narrowly Indian” (Dhondy 130).17

Outside India, in places such as post-Stalinist Soviet Union, Bollywood films provided occasions to debate sensitive topics such as ideology and pleasure publicly and safely. Bobby was voted one of the top five films in 1975 by readers of the biweekly film serial Sovetskii Ekran (The Soviet Screen, with a circulation of 2 million in 1975), who conducted a lengthy print debate about Bobby that many wrote “taught them how to love.” As the scholar Sudha Rajagopalan documents, discussions about Hindi films over any other cultural form in the Soviet press demonstrate that “it was possible to have divergent opinions about what Indian films represented to the audience, voice them publicly, and continue to engage with each other in the public space of the movies in post-Stalinist society.”18

Audiences in Nigeria, the anthropologist Brian Larkin has shown, flock to Bollywood films, preferring those from the Golden Fifties (such as Mother India, Mehboob Khan, 1957) to more recent offerings. As Larkin explains in his ethnography of media in predominantly Muslim northern Nigeria: “the visual subjects of Indian movies reflect back to Hausa viewers aspects of everyday life . . . [that] fit with Hausa society . . . [and] offer an alternative style of fashion and romance that Hausa youth could follow without the ideological baggage of ‘becoming western.’”19 A scene indicating similar preferences and even similar tensions is played out in East Is East (Damien O’Donnell, 1999), when the miniskirt-clad British-born daughter of a Pakistani fish and chips seller joyfully dances to a song from the courtesan hit, Pakeeza (The pure one, Kamal Amrohi, 1971), while her family has its one on-screen cuddly moment in a Bradford cinema’s screening of Chaudhvin ka Chand (Moon of the 14th day, Mohammed Sadiq, 1960).

For Bollywood’s fans in India and elsewhere, the cultural product represents a cognitive horizon crucial for organizing an understanding of modern life and enabling an acceptance of it. Its blockbusters provide a symbolic cultural space of social resolution for the many who were alienated (as in the Soviet example) or left behind (as in the Nigerian case) by the print industry and its putative work in fully literate societies. Not only are Bollywood’s blockbusters products of the age in which they are made and circulate, they are also producers in their own right whose images, conflicts, and associations acquire a power and authority often independent from and in excess of the whole. The cinema works, as popular forms do, not just by reproducing itself or its main preoccupations. It works by enabling its consumers to nimbly refashion the text to their own ends. When modernity appeared more a threat than an opportunity in India, film played a role in appeasing its demons. Bollywood’s enchantment lay exactly in its flexibility. Through image, lyric, and narrative, its multiple codes embody messages not always in concert yet always coherent. Thus, Bombay’s confections trolled the globe, a traveling market of film capital that stopped short of U.S. borders.

THE WORLD ACCORDING TO HOLLYWOOD

In 1998 the Indian government granted “industry” status to commercial cinema, enabling productions to access bank financing and loans for film development. The influx of capital, combined with the release of crowd-pleasing films such as Hum Aapke Hain Kaun? (Who am I to you?, Sooraj Barjatya, 1994) and DDLJ (1995) renewed Hindi cinema and inaugurated a phase that some scholars name the New Bollywood. India’s media environment continued to change rapidly: cable made way for satellite television and the internet, and wider distribution, new screening platforms, and a new professionalism seemed to gather around the Hindi film industry. If we began by asking whether Bollywood could make it in Hollywood’s turf, it seems equally germane to ask if Hollywood’s methods might transform Bollywood’s ways. In other words, do funds create the cinema, or does cinema create the funds? A glance at Hollywood’s “world” may be illuminating in understanding how differently the two major film industries work in their quest for global markets. In contrasting the Bombay film industry with Hollywood, the profoundly different fiscal logics and loci that organize each are immediately apparent.

TABLE 4.1 The Economics of Bollywood vs. Hollywood

1. KPMG-FICCI, Digital Dawn: The Metamorphosis Begins, Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report (2012), 59–76 (revenues reported in INR are converted at the 2012 rate of INR 50 to US$1); see www.in.kpmg.com/securedata/ficci/Reports/FICCI-KPMG_Report_2012.pdf (accessed June 2013).

2. Motion Picture Association of America, “Theatrical Market Statistics: 2012”; see mpaa.org (accessed June 2013). The 2012 global box office for all films is reported at $34.7 billion, with $10.8 billion from U.S. and Canadian sources (ibid., 1).

3. Yassir A. Pitalwalla, “Hollywood vs. Bollywood,” Fortune 152.10 (Europe), November 28, 2005.

Table 4.1 provides a snapshot of the Bollywood and Hollywood industries from reports compiled by official sources.20 Three main points are immediately evident. First is the scale of the Bollywood industry in contrast to Hollywood’s and Bombay’s notable undercapitalization in the comparison. Revenues from Bollywood’s productions ($1.86 billion) comprise only roughly 5 percent of cinema’s global revenues at the box office ($34.7 billion). Second, Bollywood’s revenues are less than 20 percent (i.e., 17 percent) of Hollywood’s ($10.8 billion). Nevertheless, despite lagging in global revenue and gross earnings, Bollywood’s worldwide ticket sales ($3.6 billion) are almost 40 percent higher than Hollywood’s ($2.6 billion). Third, despite the chaos in funding, a business model that makes most financial managers cringe, and the fact that according to an Ernst and Young report, 30 percent of Bollywood’s films that start shooting are never completed and 90 percent of Bollywood’s films fail to recover their costs,21 the Bombay film industry has seen an annual growth rate of between 12 and 20 percent. In contrast, Hollywood’s industry, famously overseen by corporate managers, has been steadily dwindling in growth to under 5 percent a year while it loses domestic and worldwide audiences and sees losses at the U.S. box office. In short, the Bollywood profile appears to challenge any positive correlation between business oversight and economic return.

Prior to being recognized an industry in 1998, Bollywood was quite literally a cottage industry, absent reliable financing for its projects. The cottage industry, which was heavily taxed by a suspicious state, was mainly self-funded by sources intrinsic to it, such as film distributors. There were sporadic influxes of capital from private sources such as rice farmers after a particularly good harvest,22 or diamond merchants such as Bharat Shah, who produced Devdas (Sanjay Leela Bhansali, 2002), once the most expensive Bollywood film ever made (at the cost of $10.2 million).23 Notable among these sources were distributors with their intimate knowledge of regions and audience, who provided financing for productions that would appeal to their target region. It is arguably the case that it is distributors and their insistence on serving their audiences (rather than serving their directors or producers) that made Bollywood what it has become.24

This erratic funding created a cinema of great internal variety, with forms including mythologicals, action and stunt films, Muslim socials, dramas and melodramas, detective and crime thrillers, historical sagas, social films, romances, war films, and slapstick. The diversity of offerings includes within it common formal elements of music and dance around a shared cinematic vocabulary—a particular handling of shots, an increasing affection for exotic locations, a persistent crossing of generic boundaries, an acting style that veers toward skiagraphia (which emphasizes broad gestures rather than lexical precision), and a frequent disregard for the unities of time, place, and action. The typical Bollywood film still screens in a large theater not unlike a nineteenth-century opera house (also the name of one of Bombay’s grandest movie theaters) with thousand-plus seats divided into carefully niched classes according to a staggered economy that places the unwashed masses in the front stalls, on benches, or on the floor, with ladies and middle-class families spread across the balcony and the highest price dress circle. The railway is the only other public space in India where such social diversity voluntarily occupies such a limited space. Like the train, the movie audience is separated according to class in regulated but porous compartments, each class aware of the other’s presence but spared physical and often even visual contact. Because of the sheer size of such theaters, a film had to play to every sector of the audience enough of the time to draw every sector in for the three bread-and-butter showings at noon, 3, and 6 p.m.25 Under these material conditions, a Bollywood film must purvey a bedrock of familiarity to signal its widest possible appeal. A filmmaker could not make a niche film and expect financial success; nor could the theater owner count on a niche audience to fill a thousand-seat hall day after day, year upon year.

In an industry dominated by exigencies of production and distribution such as this, it is no wonder that a cinema that could fill thousand-seat theaters with homemakers, adolescents, retirees, factory workers, domestic servants, families, taxi drivers, bureaucrats, and college students came to be associated as the national cinema. One conundrum that many ask is why Bombay travels as well as it does. Part of the answer must surely lie in the industry’s unwillingness or inability to circumvent the material challenge of filling the thousand-seat theater. It made movies to fill them and ended up with a cinema for the billions. The filmmaker Shyam Benegal calls Hindi cinema “pan Indian, and a generalist cinema,” elaborating: “Hindi films tend to travel much more than regional films. . . . Its common denominator has to be extremely wide and it has to appeal to a very large number of people. So the subject matters and treatment of the subject matters in a Hindi film tend to be far more generalized.”26

Both the financing of Hindi films and their distribution and screening have begun to change markedly. The thousand-seat movie palaces have rapidly begun to be replaced by multiplex screens in large metropolises and midsize cities. The justification has been that the smaller screens encourage a diversity of content. No longer will a film need to appeal to a broad audience day after day. Rather, the smaller screens, it has been argued, allow distributors to pick up films earlier deemed too risky or too specialized for the mass audience. “The era of big cinema is out,” claimed Raj Chopra of the Competent Group in 2002.27 Multiplexes enjoy tax-free status on profits in many states where their construction in malls twins retail with entertainment, both intent on capturing a demographic that the anthropologist Ron Inden has dubbed the “bubblegum crowd.”28 In contrast to single-screen theaters that were constructed in densely populated urban areas easily accessible by public transportation, sociologists Adrian Athique and Douglas Hill document that “multiplexes have been constructed in suburbs . . . [that] must be reached by private rather than public transport.” The result is what Athique and Hill call a “sufficiently sanitized and controlled public space where the behaviour of patrons corresponds with middle-class norms and where the overwhelming numerical superiority of the mob is mitigated.”29 The “big cinema” appeal to “big audiences” of the past half century is now reconfigured in what the media scholar Amit Rai has dubbed the “malltiplex,” where middle- and upper-class viewers can make a “lifestyle statement” (Athique and Hill 67) as they view similar statements projected by the content on screen.30 The process of gentrification that Tejaswini Ganti observes in Hindi cinema is not just a matter of gentrifying content for smaller screens. The construction and location of multiplexes also gentrifies the screening experience and isolates it from the masses putatively dreaded by the middle and aspirational classes.

Alongside changes in screening, the elevation of film from cottage industry to a state-recognized industry in 1998 ameliorated the hitherto in-house financing situation in Bollywood. Now “bonafide” financing sources such as multinationals and venture capitalists see film as a ripe space for investment. Even India’s Catholic Church has gone Bollywood, producing a film about sex, religion, and AIDS called Aisa Kyon Hota Hai? (Why does it happen like this?, Ajay Kanchan, 2006).31 A special report in India Today describes how such corporate efficiency works in the industry: “Audited by Ernst and Young, a specially designed software programme breaks down the entire screenplay of the film, taking stock of every detail: from the budgeting to the colour of Bipasha Basu’s clothing for a particular shot.”32

The old Bollywood was characterized as a place penetrated by Archie comic books and divine inspiration (Sholay was germinated from a four-line idea that Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar sold to the Sippys in 1973).33 It is a cinema that made history—and the nation. Backers of the new Bollywood include global media giants such as Sony and Twentieth Century Fox and global steel magnates such as Lakshmi Mittal, who financed the media arm, B4U, Mittal’s first non-steel venture. Banks, which had shied away from the industry since its inception, are now eager to support it with loans, though the onerous paperwork requirements keep borrowers away. According to one insider, “financial institutions are not very happy with the number of loan applications they receive for movie projects. The Industrial Development Bank of India, for example, gets only 30–40 applications a year. Most producers are not willing to get involved with the documentation and paperwork that precedes the sanction of a loan.”34

The “reformed” film industry, run by MBAs and accountants, is now rife with practices apparently learned by business school case-study methods, echoing Hollywood’s focus groups. As Gitanjali Kirloskar of the venture capital arm of the multinational, Lintertainment, claims: “We want to help in professionalizing the industry from developing scripts to testing story-lines.”35 Meanwhile, iDream, an offshoot of the securities firm SSKI, is reportedly “keeping an eagle eye on the finances of debutant director Robby Grewal’s Samay. Bhatnagar [the back office suit] won’t even look at films with no bound script or storyboard. His aim: ‘We want to produce sensible cinema as well as make money.’”36

Bhatnagar’s is a lofty aim, though it remains to be seen whether the “sensible cinema that makes money” actually comes off of a bound script, or whether it was better inspired from the legendary late-night sessions at Raj Kapoor’s cottage in Chembur that produced hits like Awara and Bobby. Notwithstanding claims of professionalizing this informal culture, recent reports seem to indicate as high a failure rate as Bollywood itself. Only about a dozen or so of the films made with the new corporate financing mantra have actually made it to screens. The year 2002, when the influx of new capital was at a high point, has been regarded as one of the worst in Bollywood’s recent memory.37 Indeed, 94 percent of the films released that year (or 124 of 132) were flops incurring losses of $58 million.38 Meanwhile, the dark cloud in the multiplex boom already seems evident. While the break-even point in Western multiplexes occurs with 10 percent occupancy, in India, with higher infrastructure costs and building taxes it is 40 percent.39 And that, it seems, brings the multiplex back to where the movie palace once was: obliged to screen films for the multitudes.

The details on the new corporatized industry underscore what might yet happen in Bollywood, that it too might follow the uninspiring destiny that Hollywood has claimed and become that abhorrent form of mass culture instrumental in the alienation of its audiences. But Bollywood has yet to succumb. The influx of new funds has not seen many results. Sony got burned after its venture in 2000 with Mission Kashmir (Vinod Chopra), which grossed only $590,000 in the U.S. box office. The Industrial Development Bank of India has more funds to loan than applicants, and its one “hit,” Mangal Pandey: The Rising (Ketan Mehta, 2005), appears nowhere in the top 200 list of box office grossers.40 Most film IPOs on the Bombay Stock Exchange are trading for paisas despite their initial buzz, even while the broader stock market sees double-digit increases. A report in the Wall Street Journal cautions that “investors might want to stick to buying cinema tickets rather than shares in the country’s moviemakers.” With its “opaque management practices and unclear, if not downright murky, deals for financing and distribution,” the industry is considered too “difficult” and “fragmented” to be understood by outside investors, be they Indian or not.41

Overall, the Bollywood industry remains a diffuse site of production with intimate if unsystematized ties to its audiences. Aditya Chopra made film history with DDLJ, the longest-running Hindi film at over 800 weeks, by making a film for his friends, scoring again with Bunty aur Babli (Bunty and Babli, 2005), a runaway hit among small-town youth audiences whose frustrations it affectionately portrayed. Meanwhile, Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham (K3G), made by Chopra’s childhood friend and colleague, Karan Johar, is one of the most successful Hindi films to circulate in the United States and the UK. (Johar’s earlier film, the trendsetter Kuch Kuch Hota Hai [Something happens, 1998], earned £1.75 million in the UK and $2.1 million in the United States; K3G almost doubled that amount in 2001.) However, these films never enjoyed screenings for U.S. critics or distribution amongst U.S. audiences, so they never made it to the mainstream multiplex at the mall. As one scholar documents, K3G created a “minor scandal” when “the film should have appeared within the top-10 box office in the United States on Variety’s lists for late 2001, but [it] was omitted because the [Variety] editors apparently couldn’t believe that an ‘unknown’ film was doing ‘house full’ business in American theatres (albeit those catering to Indo-American audiences).”42 The neglect of Hindi films by mainstream U.S. outlets has changed considerably in the last decade, and it is now commonplace at the time of writing to encounter reviews of Hindi films in the New York Times on Fridays alongside the latest Brad Pitt or James Bond release.

Reviewing these statistics, it is evident that Bollywood’s presence is already apparent in the United States even if its popularity seems largely a diasporic phenomenon.43 Its box office returns might appear small when compared to Hollywood’s on table 4.1, but they are in fact substantial in Bombay’s own terms when its lower production costs and purchasing price parity (PPP) are taken into account. These observations urge a renewed reckoning of Bollywood and Bollywood-themed imports into the United States. Might reviewing which films succeed over others render clarity over what imports travel better than others into U.S. markets?

The data on table 4.2 illuminate several points. First, of the five top-grossing Indian films in the U.S. market, those from the “real” Bollywood, made in Bombay in Hindi with locally grown directors, financing, production, and distribution, trail in the U.S. box office far behind the carefully deracinated versions that grossly copied its affects (thus, K3G’s $3.1 million in the United States in contrast to Monsoon Wedding’s $13.9 million).44 Second, returns in the U.S. box office notwithstanding, the three top-grossing Bombay-produced films in the U.S. market are in fact considerable laggards among the 200 all-time top-grossing Bombay films (adjusted for inflation). In this pantheon, the trio on table 4.2 appear nowhere near the top. K3G is at #72, 3 Idiots at #33, with Don 2 entirely absent from the list at the time of writing. Meanwhile, seventeen of the top twenty all-time highest-grossing Hindi films through 2012 (adjusted for inflation) were made in the long 1970s, with the list including Sholay at #1, Amar Akbar Anthony (#5), Bobby (#6), Deewaar (#11), and Trishul (#12).45 These two details hint at a complex backstory about the nature of Bollywood’s hits that is worth scrutinizing.

TABLE 4.2 The Five Top-Grossing Hindi Films in the United States

All figures adjusted for inflation.

Sources: “International Business Overview Standard” at http://ibosnetwork.com/usatopgrosses.asp; http://ibosnetwork.com/uktopopenings.asp (accessed June 2013) and boxofficemojo.com (accessed June 2013).

There is no doubt that the financial data that profile these films are highly suspect. The industry notoriously underreports its profits at every level to avoid tax liability, and the figures are routinely “adjusted” to account for this. Yet the statistical corruption is so widespread and widely acknowledged that the figures, however distorted, are the best index (in fact the only one) to profile the industry. They provide quantitative corroboration to the symbolic capital that specific films have accrued as evident from qualitative sources, which affirms the data’s general, if not particular, accuracy.

The continued box office dominance of films from the 1970s underscores the influence that the decade and its products continue to have almost half a century later. Furthermore, in a marketplace dominated by the domestic box office, films that are top grossers in the United States flounder.

It should be no surprise that films that are popular in one context may not be in another. Therefore, that a version of Bollywood I name Bollywood Lite—or Bollylite—sold better in the U.S. multiplex than it did in India is not particularly unexpected. Bollylite’s specially charged confection with sexual predation, expensive automobiles, and romance appears destined to cross borders with little obstacle, as Monsoon Wedding so successfully demonstrated. In this context, the director Mira Nair called Monsoon Wedding “a Bollywood movie, made on my own terms.”46 The critical story, however, lies in the U.S. fortunes of the films listed in table 4.2 (such as K3G), which were produced and made in and for an Indian audience before traveling West. Examining the success of these Bombay productions in U.S. theaters may explain something about the forms of Bollywood that can make the journey to the United States and find commercial success there. Unfreighted of many of Bollywood’s familiar locational and cultural markers, Bollylite is both leaner than its shaggy antecedents, and possibly lesser. The suffix “lite” gestures at least initially toward the pruning of a cultural brand in preparation for the U.S. market. Whether “lite” also comments on the substance in these films will become clearer shortly.

K3G

The U.S. success of a film such as K3G has often been explained by its extraordinary production savvy, which can hold its own against just about any Hollywood export. Packaged for theatrical release and video sales with slick advertising and catchy bylines that circulated on the internet, the film is subtitled in more languages spoken outside the Subcontinent than within, including French, German, Spanish, Arabic, Dutch, Malay, Japanese, and Hebrew. Its content reveals a skillful command over style, fashion, editing, color, and makeup to render it visually current with global trends if not fully coherent. K3G’s non-resident Indians (NRIs) with their Armani suits, designer saris, and flashy gemstones provide a relentless spectacle of an aucourant consumer utopia unfettered by taste or modesty to become one of the highest-grossing Bombay exports in the U.S. box office.47 “Bollywood” in form, this film departs markedly from earlier blockbusters in its systematic embrace of the material world. Produced at a moment when the new financial instruments and technological innovations described earlier enabled the enhancement of the Bombay industry, Bollylite films illuminate a cinema in which new technology and financial priorities have penetrated and become the inner logic of everyday life. No film better elaborates the idea of Bollylite than Karan Johar’s K3G.

Dubbed “The Indian Family” in France and Germany, K3G paired reigning screen star Shah Rukh Khan with Amitabh Bachchan in a reprise of their blockbuster pairing from Mohabattein (Lovers, Aditya Chopra, 2000). Inhabiting a Delhi house curiously identical to Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild’s Waddesdon Manor in Oxfordshire, this Indian family consists of a stern industrialist father, played by Amitabh Bachchan, a successful corporate son, played by Shah Rukh Khan, and a bevy of doting and devoted wives alternating saccharine smiles and domestic piety as if their lives depended on it. The remark is not in vain: their lives did depend on diligent devotion to something Corey Creekmur has wryly called industrial strength patriarchy. The son crosses the father by marrying a woman of his choice; the father disowns the son, who leaves India for London where he makes easy millions at an unspecified job where he can leisurely get to work by lunchtime; the two eventually remeet in a British shopping mall and tearfully reconcile after a decade-long estrangement.

It is no coincidence that labor is invisible in K3G: it tends to be that way in most Bollylite films that showcase wealth in an effort to capture the attention of the aspiring classes.48 What is visible in this film is surplus capital, repeated over and over again in the lavish display of name-brand luxury. That the estranged father and son can reconcile, not in the family home in Delhi but in that special emporium of consumption, the mall, is an irony unremarked upon in this connection, for Bollylite has little time for such narrative subtleties.

In K3G, the logic of the marketplace replaces all human relations, even filial piety. Whereas the mother cuddles her son in the prayer room at home, the father reserves parental cuddling for his place of worship, namely, a well-appointed suite in his corporate headquarters where he emotionally hands his family (i.e., his business) to his heir (see fig. 4.14). The son reaches his father’s stature not by his moral integrity (in keeping his word to the woman he loves) but by the acquisition of millions, which makes them equals by the end of the film. The father punishes the son’s breach to family honor not so much by cutting family ties, but by cutting him from his share of the family corporation. The exile the son chooses is not to remove himself from his father, but to find economic opportunities to best his parent’s. While in London yearning for the paternal embrace, the son reverentially places a giant photo of his parents above his household gods, specifically, a giant state-of-the-art flat panel television (fig. 4.9).

“It’s all about loving your parents,” claimed the publicity banner (fig. 4.10) for a film in which that love finds its best mediation in models learned from the media and television that the flat panel displays. Media is the message here, and it could not be more severed from substance.

Larded with patriotism stirred by the indiscriminate playing of all three of India’s patriotic anthems, the son’s diasporic family gets teary-eyed longing for “home” all the while impervious to the transformations that “home” is undergoing as a consequence of the market values they usher into it. The concepts of family, duty, and nation exist largely in relation to the market in the film. Economic liberalization and its aftermath provided new capital and social impulses that K3G exploits in its treatment of the familiar trope of family melodrama. As the scholar Meheli Sen observes, in the 1990s “Bollywood fashioned a new family to articulate the nation’s vicissitudes.”49 In this “new” family, both tradition and patriarchy are skillfully retrofitted within the logic of the market and made to reinforce the market’s priorities. The refurbished “family” is an extension of the corporation, supported by mergers (marriages) that extend the corporate entity. Boardroom protocols dictate kinship alliances. Infractions within the family—such as the son’s refusal to marry a woman of his father’s choice—lead to ejection from the boardroom and the family, as the son’s exile in K3G underscores.

FIGURES 4.9 AND 4.10 The immigrant home in London, where “it’s all about loving your parents”—and your stuff (K3G, 2001).

(COURTESY YASH RAJ FILMS)

Anchored to a fantasy of “tradition” comprised of consumer goods and massive mansions, K3G provides a special form of comfort to salve the nostalgia of India’s prosperous diasporic elite. Money, love, and family become interchangeable: having the first generates the others, or some simulacrum thereof. The prayer room has given way for the mall, the family for the television. Cinema’s self-critique of media made famous in Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955)—with Jane Wyman’s despair blankly reflected off the new television set meant to assuage a loneliness that only the forbidden Rock Hudson can fulfill—has gone the way of irony in Johar’s Bollylite exemplaire.

These remarks underscore the superficiality of a hit that even its director has since called “candy floss.”50 The earlier gulf between a film’s manifest and latent content evident so consistently in blockbusters such as Bobby has largely disappeared. K3G’s conservative social values and misogyny are rendered attractive by the visual glitz of its production. Form is content in Bollylite, and the two are seamlessly packaged to slide by an onerous demand for value. Paradoxically, the forms in which Bollylite travels to the West shear its politics and social critique but preserve its formal features. Thus, if K3G is a reliable indicator, there is more dance, not less in it; more melodrama, not less; more family, not more individuality. Rather than diluting form, Bollylite concentrates it. What it dilutes are political and social substance. What you see is what you get in this new kind of blockbuster that played so well to the diasporic crowd at the U.S. multiplex. The multiplex’s smaller screens were warmly justified in India on the grounds that they enabled smaller films to prosper: those made on smaller budgets, with smaller stars, for a smaller audience—such as indie films (sometimes called hatke) that have prospered in this new screening opportunity. But Bollylite’s offerings have equally prospered in the multiplex, with their large production budgets and scale balanced by a considerable diminishment in subtlety and substance. The exigencies that dominate the thousand-seat theaters still operating in most parts of India mean that film producers still have to entice a variety of viewers in order to expect predictable returns. Smaller screens both in India and elsewhere remove some of that urgency. They offer the promise of more diverse fare, but at the cost of a fully diverse audience. The outcome is a diminished cinema and product, as K3G demonstrates.

It would be too simple to claim that multiplexes create vapid fare. But the changing economics of the Bombay film industry, with new forms of financing, new business models, new investors, new distribution networks, and new corporate ownership of exhibition spaces is certainly having an effect on the industry’s products. In 2002 an optimistic entrepreneur exulted at the “latent demand for destination entertainment” in the country.51 The rise of the multiplex alongside India’s new shopping malls gave new purpose to brand identities. The cinema spun a visual fantasy that the mall then delivered in the commodities it purveyed. The two became what the writer Ratna Bhushan calls “synergistic retail partners,” both hedging risks on their investment. Should the film not deliver a purchasing fantasy, the mall and the film both flop in this sort of relationship. To avoid that outcome, one multiplex executive insisted, “we will backward integrate into film distribution and subsequently into film production. That will evolve as a general industry trend.”52 How plausible that relationship might be for the long term remains to be seen.53

Products like K3G point to one possible outcome of the new relationship. There is no evidence available of backward integration in producing this film, but there is every evidence that its content collaborates well with the consumer values of the new post-liberalization economy both in India and in the United States. K3G’s success as a top-grossing Hindi film in the U.S. says as much about the particular film’s ability to travel as the conditions under which that journey is possible. While the considerable industry muscle of Johar’s company, Dharma Productions, got the director permission to shoot lavish dance sequences in Leicester Square and even at the venerable British Museum, none of that gave K3G the symbolic (or even box office) capital that Sholay and Awara continue to enjoy in the decades since their release.

I do not for a moment mean to suggest that blockbusters of the earlier period did not contain their own commodity fantasies. Both Awara and Sholay are centrally about the quest for stability that comes with financial security. When Veeru asks Jai in Sholay about settling down in Ramgarh, it is fully evident that the migrant laborer can only dream of acquiring a home because the cash to purchase it has finally come into sight. In Awara, the quest for financial stability is layered with the search for paternity and the social integration it affords. Yet the fiduciary objects are not ends in themselves as the luxury goodies in K3G are. Virtually all the protagonist’s exploits in Awara involve getting things for the women in his life that his biological father has withheld from them. In these earlier films, commodities, economic stability, and the market are means to an end far bigger than the sum of the parts. At the same time, the parts are subject to critique for obstructing individual agency and social decency. Thus, when Raj in Awara attempts to reform from a life of crime, his exploitation in the hands of a local factory owner is critiqued as well as the poverty that criminalizes him in the first place. Neither the commodity nor the market of which it is part is fully embraced in these films, even while both are being eventually mastered by protagonists as different as Raj and Veeru. In Bollylite, to the contrary, the market is the end, and mastering it is the happy ending that arrives in a mirage of goodies meant to fill a void that must not be named.

As India’s economic liberalization program concludes its third decade and the distance between it and the West shrinks, the earlier clashes with modernity have now become full-fledged warfare. If Raj Kapoor’s Awara showed the clash between three generations and three economic orders (the feudal class of landed property, the professionalized post-Independence elite that sprang from the squirearchy, and the “new” class represented by the tramp; see figs. 4.11–4.13), the clash these days is between two generations (father and son in K3G), inhabiting the same economic order (fig. 4.14).

The earlier critiques of a market-dominated logic, the insistence on separating economic wealth from social worth that was so keenly detailed in Kapoor’s films of the 1950s and that persisted in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s 1970s comedies of the middle classes and Manmohan Desai’s blockbusters for the masses have largely disappeared.54 The subalterns and their struggles have no place even in Bollylite’s hairline margins. Bollylite’s issue is no longer making it (“it” being financial security, social position, community integration): those things are given, if we believe Bollylite’s tales of the fabulously wealthy. The real issue now is being it: “it” being the good Indian who has evaded any conflict from succumbing to the pleasures of material desire in the climate of economic liberalization and Westernization. In this regard, Monsoon Wedding may not be as different from K3G as its box office returns in the United States might anticipate, even as both are profoundly dissimilar from the cinema christened Bollywood and detailed in the first section of this chapter.

FIGURE 4.11 Prithviraj Kapoor as landowner in Awara (1951).

(COURTESY YASH RAJ FILMS)

FIGURE 4.12 Prithviraj Kapoor as judge in Awara (1951).

(COURTESY YASH RAJ FILMS)

FIGURE 4.13 Raj Kapoor as tramp in Awara (1951).

(COURTESY YASH RAJ FILMS)

FIGURE 4.14 Amitabh Bachchan and Shah Rukh Khan in K3G (2001).

(COURTESY YASH RAJ FILMS)

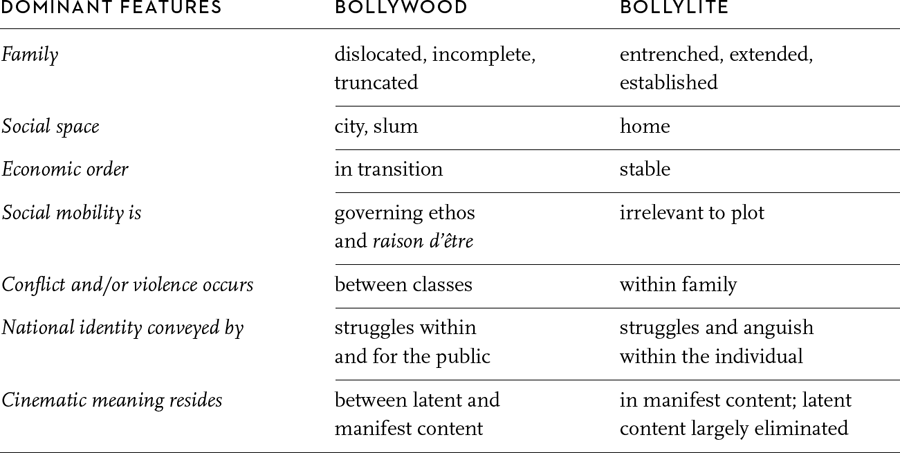

Table 4.3 gathers some of the most striking differences between a cinema of substance and one of image conveyed in the terms Bollywood and Bollylite, respectively. For Bollywood to travel to the U.S. multiplex, it needs to be shorn of its substance, its contradictions, and its coherence. Indian modernity in the new iteration is one that carries a sacrosanct tradition untouched, unmodernized, and unexamined with it.

TABLE 4.3 Bollywood vs. Bollylite

The table is indicative rather than prescriptive. It condenses the analytic arguments of this chapter in an effort to sharpen an understanding of a cinema at a moment of transition as that cinema crosses its Rubicon—or the Mississippi. One could immediately think of exceptions: Bollywood films such as DDLJ with many of Bollylite’s formal characteristics, or Bollylite films such as Hum Aapke Hain Kaun? with numerous typically Bollywood features. Both sorts clearly proliferate and coexist. Table 4.3 highlights a set of dominant features of the cinemas that I differentiate into the forms Bollywood and Bollylite. These are by no means the only features that characterize the differences between the two. They simply happen to be most marked in this analysis. The seepage of features across the two cinemas is to be expected. Bollylite owes its identity and origin to Bollywood and adeptly borrows from it when it can, even as it brutally unfreights itself of matter deemed too heavy for its global travels. Thus, the clarity of formal features as outlined in table 4.3 is not perfectly reflected in this fecund industry, nor should the difficulty with taxonomic precision necessarily obviate the larger argument in table 4.3.

In the end, the real question may not be so much whether Bollywood travels to the United States as Bollywood’s travels in multiplex circuits both in the U.S. and in India. The Indian multiplex phenomenon indexes a larger transformation of a booming globalized economy and its domestic social changes. For some observers, this “new” Indian world resembles the United States in more ways than one, with a markedly alienated and depoliticized relationship between culture and consumption. Social capital is in decline in this world; commodity capital appears in some quarters to have taken its place. In such an environment, where the NRI and the wannabe NRI are such visible players, films such as K3G have considerable appeal. K3G’s travels gesture toward the proliferation of a set of values that coexists with those that Bollywood purveyed in the post-Independence period and that Farrukh Dhondy observed a quarter century ago.

Bollywood, however, has yet to disappear as the success of hits such as DDLJ and Bunty aur Babli attest. For now, it coexists with Bollylite. Both products in this iteration serve as compensatory narratives in all senses of the term. The greater India’s embrace of modernity, the firmer its step into the dance of global capital, the stronger the likelihood of Bollylite’s proliferation. But that proliferation remains destined for the multiplex, and its fortunes tied to a form that even today plays to a minority of the twelve million a day who go the movies in India. KPMG’s 2012 industry report (Digital Dawn: The Metamorphosis Begins) observed the multiplexes’ “dismal footfall over weekdays” and cautioned: “High property prices and recent recessionary conditions have slowed the expansion of malls and corresponding footfall growth which has directly affected the growth of multiplexes” (KPMG 2012:65).

At a moment where a little over 1,000 (or approximately 8 percent) of India’s 14,000 cinema screens are multiplex, large-capacity single screens still dominate with their content devoted to capturing the largest audience possible (see KPMG 2011:61; 2012:64). With twelve screens per million people in India (or approximately one screen for every 83,000 people), going to the movies is a crowded undertaking.55 The malltiplex has done much to ease the gentry into more comfortable seats, and Bollylite’s offerings have helped further anesthetize their sensibilities from civic engagement. The political and social responsiveness that dominates Bollywood have become economic farces in Bollylite’s offerings. If Bollywood, exemplified by the cinema of Raj Kapoor and blockbusters such as Deewaar, captured national fantasies to bring everyone along rather than alienating one section from another, Bollylite’s offerings erase whole sections of the public altogether. Its India is scrubbed clean of labor and poverty. K3G’s Chandni Chowk comes in soothing pastels without open drains or germ-infused chutneys. Its Delhi mansions look awfully like English country houses, the weather is always amenable, and perilous Delhi buses are replaced by sleek private helicopters that deliver Shah Rukh Khan home in time for a party to celebrate his father’s most recent corporate takeover.

But the India of slums coexists alongside its high-rises. This is the India that Slumdog Millionaire insists on recalling when it opens with another screen god, Amitabh Bachchan, descending from another helicopter by a garbage heap. The film retrieves Bollywood’s core plot and reminds its viewers of the nation that inspired the state and the cinema that sustained it. Bollywood is always the story of slumdogs who become millionaires, of men of multiple faiths who make it in a flawed secular democracy, of movements from innocence to experience, of the hero who gets the girl and his pawned honesty medal, and of protagonists who conquer the metropolis and their lesser selves. As India changes, the cinema does as well—to an extent. It remains national, if increasingly less nationalist.

Above all, the cinema named Bollywood remains insistently a form of critique and renewal. Through the long 1970s that critique was directed at a political horizon that seemed to have failed its citizens. With economic liberalization, as several hundred million people entered the middle classes and beyond, the object of critique moved from the political back to the social and the economic. Raj Kapoor’s Shree 420 comes to an end when a group of con artists desperately chase a bag of money that eventually bursts and dooms them. The scene is oddly prescient of what occurs today in an India eager to integrate more completely into global capitalism. The bag of money has now come “home,” and everyone has a shot at getting it. Many do. However, the money brings little solace—either to the Raichand family estranged in London in K3G, or to Salim Malik, Jamal’s brother in Slumdog Millionaire, who is shot in a bathtub full of rupee notes. Bollywood, and the forms that honor it, allow one to see that.

The United States proclaims its multiplexes break even with 10 percent occupancy. With such figures, one has little to fear that the multiplex will transform a cinematic form that has kept billions rapt across the last century. Bollywood may not travel to the U.S. multiplex; but Bollylite will, and it will likely prosper there. And one day it may even awaken its audience for the real thing.