Chapter 17

Isurava

‘The Nankai Shitai…have succeeded in completely surrounding the Australian forces…The annihilation of the Australians is near’

—Major-General Horii Tomitaro, commander of the Japanese troops at Isurava

A scene of grotesque beauty surrounds what was Isurava. The ‘forces of nature gone berserk’ was one apt description.1 The original village stood on the great spur jutting out over the Kokoda plateau. It is possible to imagine this place as a huge, north-facing amphitheatre. To the east, Eora Creek rushes heard but unseen down the deep gorge, and high up the far side, on the eastern ‘dress circle’, is the village of Abuari, shrouded in the mist of a waterfall. To the west, the great Naro Ridge curves around the Isurava spur like the gods of an opera house, the whole effect of which is to thrust the eye forward to the ‘stage’, the Kokoda plateau far below, where the Japanese army massed.

The Australians had a strong geographical advantage. The corvette-shaped valley offered a brilliant defensive position. The country immediately beneath the spur is a steep, heavily forested slope, up which Horii’s troops were forced to climb. To reach the high flanks—the ‘arm-rests’ east and west—from where they could enfilade the Australians, they had to ascend mountainsides through virgin jungle.

Indeed, it is tempting to speculate that when they spoke of ‘The Gap’, Allied GHQ actually meant Isurava (so poor were their maps). Lieutenant-Colonel Ralph Honner perhaps unwittingly made the allusion: ‘Isurava could yet be Australia’s Thermopylae,’ he wrote.2 It was ‘as good a delaying position as could be found…If the enemy…should try to outflank us they would face a stiff uphill climb from the Eora Valley on our right or a tedious struggle through the dense jungle round our left. And if they should choose the easy way in from the flanks they would walk into our waiting fire.’3 Honner was among the few to realise that somehow the Australians had to use the jungle to their advantage, to make tactical moves that allowed ‘the jungle itself to do the killing…’4

Numerically, the Japanese had a massive advantage—but not as great as many think. The legend of Isurava holds that one tiny, ragged Australian unit withstood 10,000 or even 13,000 fanatical Japanese combat troops, at a ten to one advantage, for weeks.5 The truth avers that about 6000 Japanese combat troops confronted some 1800 Australians, of whom 600 were untrained militia (the 39th and 53rd) and 1200 were AIF (the two battalions fought at half-strength or less). At the height of the battle, 28–30 August, there were perhaps three or four Japanese to one Australian.6 At no point along the track did the Australians face 10,000 Japanese.7

Honner, rushed over the range in mid-August to lead the 39th, looked on his men with sympathy and dismay. He found them sitting in drenched dugouts in their mud-caked uniforms, shivering ‘through the long chill vigil of the lonely nights’.8 They were worn out by strenuous fighting, and ‘many of them had literally come to a standstill’. ‘We were as wet as shags,’ said Smoky Howson, ‘and most of the fellas were crook with dysentery.’

On Sunday the 23rd a Protestant chaplain, Jack Flanagan, held a church service outside a hut in Isurava. Hymns were sung in the cool jungle air. Hundreds bowed their heads at prayer. ‘Everyone was in full battle dress and on the alert for an attack.’9

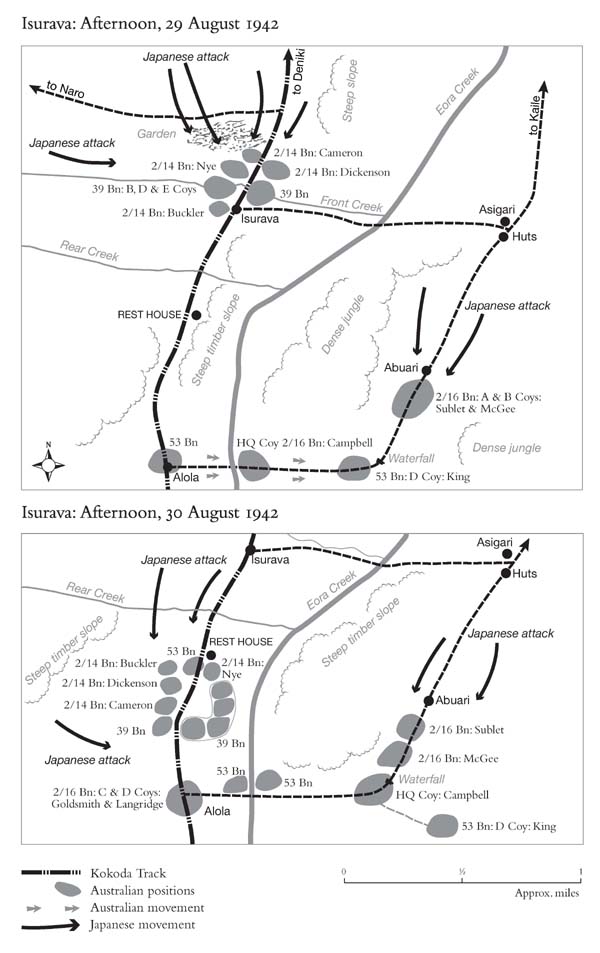

Of three possible strategies, Potts decided on the one that seemed the least costly in terms of casualties; paradoxically, it also seemed the riskiest. He planned to relieve the 39th with one fresh AIF battalion (the 2/14th), which would attack along the centre and west, up Naro Ridge. He decided also to commit the 53rd along the fork in the track towards Abuari, high up on the eastern ridge.

Potts’s over-reliance on the 53rd Battalion was the plan’s biggest flaw.10 To lose Abuari meant exposing his HQ to fire from the east. Indeed, though Potts privately doubted whether the 53rd could do the job, it was his only ‘battle-ready’ unit. They had rested at Alola for a week. It was humanly impossible to send into battle men who were just arriving over the mountains.

Early signs of the coming conflagration could be seen in the valley below, where the Japanese ‘were moving as purposefully as soldier ants’11 to the flanks—the beginnings of a vast pincer movement. In previous days, Japanese night patrols had more frequently attacked the militia’s perimeter. There were occasional suicide squads.* Selected with ritual solemnity from the Japanese ranks, such men were ordered to ‘be a messenger unto death…strive to reach your objective to the last man’.12 When Jack Boland’s section ambushed Japanese troops who ‘hadn’t fired a shot’, he felt certain ‘they’d sacrificed their blokes to draw our fire’.13

In the Japanese camp, supplies were faltering, some bags of rice had started to putrefy, but the men seemed to thrive on an apparently bottomless reserve of Japanese ‘spirit’. ‘The day was beautiful and the birds sang gaily. It was like spring,’ wrote Lieutenant Hirano, an officer in Tsukamoto’s unit at Deniki. ‘Cooked sufficient rice for three meals.’

Hirano, a Kokoda veteran, was a vivid chronicler: when six guards accidentally ‘let the natives escape’, he witnesses his commander ‘ragingly threaten them with court-martial’. When a friend was killed, he openly wept, and thought of their parents. It is tempting to read Hirano’s diary entry of 20 August as a rare example of Japanese irony: ‘20th Aug. Our new Coy Commander, 1st Lt. Hatanaka Seizo, arrived. Summary of his lecture: “In death there is life. In life there is no life.”’

That, however, would put a Western interpretation on a deeply earnest man. The triumph of death over life obsessed Hirano, as revealed in his chilling entry the next day: ‘I will die at the foot of the Emperor. I will not fear death! Long live the Emperor! Advance with this burning feeling and even the demons will flee!’14

A new arrival was Warrant Officer Sadahiro. He believed utterly in the triumph of the Japanese spirit. He led a company and carried the unit’s standard: ‘the highest honour a soldier can achieve’. He goaded his men harshly during the long march from the beach. Few of these seemed the super soldiers of Western mythology: ‘Scolding and shouting at confused subordinates, I again led the march,’ Sadahiro boasted. They marched all night. Of his 120 troops, at least 40 stragglers fell out from exhaustion. Sadahiro bemoaned their want of spirit: ‘Stragglers seem to be increasing daily. Is it because of the absence of daily training, or is it a lack of physical energy? What we need is spiritual strength!’15

Major-General Horii himself reached the heights above Kokoda on 24 August. He surveyed the battlefield, and distributed sketches of the Australian positions. He issued his last orders before battle with the gruff, perfunctory tone of a man for whom defeat was unthinkable and victory, an apparent formality (of course, Horii’s precise emphasis may be lost in translation). The word ‘annihilate’ was a personal favourite: ‘On the 26th the Shitai is to attack the enemy and advance towards Moresby,’ he decreed. The Kusunose Butai was ordered to ‘advance along the eastern side of the valley, deploy to the south of Isurava, cut off the Australians’ withdrawal and annihilate them’.16 It seemed all too simple. Horii’s main force, meanwhile, would charge up the centre and up Naro Ridge to the west, ‘surround the enemy and annihilate them’.

On the morning of the 25th a detachment of the 53rd Battalion set off on their crucial mission to Abuari, on the eastern flank, as ordered. As they trudged off, Potts had serious misgivings. He’d seen these youths coming up the track, slouching towards a maelstrom for which not even Australia’s most experienced soldiers were prepared. But Potts had no choice. They were his only rested unit.

Their first contact with the Japanese revealed a glint of steel. A forward patrol led by Lieutenant Alan Isaachsen, a South Australian bank clerk, reached the village of Kaile. As night fell, two Japanese platoons attacked with mortar bombs and machine-guns, killing him. But his men held their position and hit back with a barrage of fire. ‘Heavy casualties’ were later reported. At the time, Lieutenant-Colonel Kenneth Ward, the 53rd’s brave if inexperienced commander, couldn’t get through to Isaachsen’s men. This was because the Japanese had killed or scattered Australian signalmen at Missima, and ‘a Japanese officer, wielding his sword with theatrical fervour’ had smashed the radio set.17

Ominous news arrived. That afternoon, a 53rd officer was brought before Potts. The man had led an ‘unarmed patrol’ of 30 men towards Missima, to assist the Australian signalmen. Potts was aghast. Unarmed? The officer explained that they were to use the signal platoon’s rifles, but the (presumably heavily armed) Japanese had forced them back. The soldier’s attitude shocked Potts, who ordered Lieutenant-Colonel Ward ‘at first light tomorrow’ to recapture Missima and Abuari and restore the position on the eastern flank.18

Potts’s worst apprehensions were being horribly realised. He wired Port Moresby for urgent reinforcements: ‘53rd battalion training and discipline below the standard required.’19 It was imperative, he said, that his reserve troops (the 2/27th Battalion) leave Port Moresby at once. This demand was not met.*

This, then, was the state of Potts’s force as battle began: his supplies were inadequate; he had no troop reserves; and he faced an enemy four times the size of his exhausted force, almost half of whom were virtually untrained.

Horii’s heavily camouflaged troops moved up the mountain in swift bursts; some were so thickly adorned in vegetation they resembled moving shrubs. An unending line scaled the Naro Ridge above Isurava; to the east, they advanced towards the Abuari waterfall; and in the centre they came up the Kokoda Track from Deniki.

Sadahiro led the night movement on the 25th: ‘Today [we] became a flanking party…Faces of the warriors were tense. At 1400, while advancing up a breath-taking cliff, No 5 Company encountered and fought the enemy…Fully realised that the enemy is not to be underrated. At 1700 [we] became the advance party. Slashed ahead through the jungle all night long.’20

Dawn the next day found Australia’s 39th Battalion—of whom there were about 300 left—‘crouching like pale ghosts’21 in their dugouts at Front Creek, near Isurava village, atop the main spur. Honner deployed B Company—accused of desertion at Kokoda—up the Naro Ridge, ‘the most dangerous sector’ (in defiance of Porter’s view that they were ‘finished as a fighting force’22, and worthy only of disbandment).*

The opening salvo in the four-day battle of Isurava struck at 7.00 a.m. Japanese Jukis spat round after round across the valley. A mountain gun sent shells crashing into Isurava village, killing two Australian soldiers. All day sporadic bursts crackled across Isurava. Fresh Japanese infantry, under cover of high grass, entered the native gardens at Front Creek. An Australian patrol returning at 5.00 p.m. ‘hunted them down through the long grass while the light lasted’ and killed eight.23

Night came. Two militia platoons a few hundred yards forward of Isurava were cut off by a ‘silent tide of attackers’ flowing undetected through the darkness. Then ‘all hell broke loose’, as the Japanese ‘stormed over the two staunch platoons, lurching around the gnarled tree-roots and leaping over the ambuscading pits, shooting, stabbing, hacking, in a sudden surge of blind and blazing fury that broke and ebbed back into the darkness from which it sprang, leaving its jetsam of death stranded before it’. Thus Honner captured the fury of the first Japanese night attack at Isurava.

The Australian wounded were helped back to the village. The dead were unreachable. The Japanese soon reclaimed the native garden. By the night of the 26th they’d captured Missima village; and were deploying thousands of troops along the high Naro Ridge.

That evening the 39th received a ‘providential blessing’:24 the first platoons of the Australian Imperial Force moved up to Isurava. The sight of these fit, experienced troops, who used their weapons with habitual ease, and who fell into the dugouts with calm unconcern, startled the militia: ‘Who are you? Where are you from?’ one of the 39th men asked. ‘We’re the 2/14th Battalion, AIF,’ one replied.25 The rift dissolved; the men embraced. It was the first time the ‘twin armies’ had fought together. ‘I thought Christ had come down again,’ the 39th Battalion’s Sergeant John Manol exclaimed.26 ‘We all did. We thought of them as gods, these blokes. They were tall and they were trained…[with] clean uniforms.’

The AIF gazed at the cadaverous troops they were relieving. ‘Gaunt spectres with gaping boots,’ one soldier said, ‘and rotting tatters of uniform hanging around them like scarecrows…Their faces had no expression, their eyes sunk back into their sockets. They were drained by [disease], but they were still in the firing line…’27

‘I could have cried when I saw them, they looked terrible,’ said Jim Coy of the 2/14th. ‘But they were terribly pleased to see us,’ said Phil Rhoden, of the 2/14th. ‘The divisions faded at once. We were Australians fighting for Australia. The mood was electric.’28

The next day disaster struck the 53rd, on the eastern flank. In line with Potts’s orders, Lieutenant-Colonel Ward sent 200 men to recapture Missima. They set off along the track at 10.00 a.m., led by Captain Cuthbert King. Near Abuari they walked into enemy patrols, and King’s companies ‘scattered’. Then an Australian—no one seems to know who—gave the order: ‘Go for your lives—the Japs have broken through.’29 The cry went up—and most of the men bolted into the jungle. A few held their ground, or were immobilised by fear. Fifteen Australian bodies—the victims of an ambush—were later found slung in the jungle. Some 70 Australian troops were absent for days, having ‘gone bush’.*

‘The Australians were seen…to be retreating to the mountain top,’ observed Japanese machine-gunner Lieutenant Sakomoto. Another Japanese soldier said bitterly, ‘The Australians won’t fight!’—as though he’d been cheated of a long-awaited stoush.30

By 2.00 p.m. Ward, with no word from King, followed with his entire HQ staff. At 3.30 p.m. they skirted the Abuari waterfall and walked straight into a Japanese ambush. Ward was the first to die: ‘Senior command of the 53rd battalion was wiped out in a matter of minutes.’31

A runner alerted Potts to the debacle: the Japanese now occupied Abuari, within artillery range of brigade HQ. Disgusted, Potts ordered the 53rd back to Port Moresby.* and rushed up the 2/16th Battalion; company by company were sent in to recapture the eastern flank, now gravely exposed.

What became of the 53rd? The fittest were assigned to labour details at Myola. One unit went back under armed escort:32 ‘Their “execution” was completed when they arrived in Moresby,’ wrote Porter, who had the decency to qualify the disgrace of the 53rd: ‘Some AIF units have suffered similarly; but there has always been someone sufficiently interested to smother the stigma attached.’33 Had someone been sufficiently interested in this battalion they might have directed their ire at the Australian military authorities who’d sent untrained, deeply stigmatised young men into battle.

Captain Merritt of the 39th was famously shaving in a creek at dawn on the 28th when a runner raced up with news from the Isurava front. Honner turned to Merritt and calmly said, ‘Captain…when you’ve finished your shave will you go up to your company. The Japanese have broken through your perimeter.’34 Merritt was ‘off like a racehorse’; he arrived to find his men resisting a series of ferocious attacks. All day the 39th held, shored up by fresh AIF troops then pouring into their dugouts.

Mortar and machine-guns again opened up across the valley that afternoon, from Naro Ridge to Missima. A fastidiously time-conscious Japanese diarist noted: ‘At 1538 our guns all joined in together and the advance began along the whole front.’35

‘Mortar bombs and mountain gun shells,’ observed Honner, ‘burst among the tree tops or slashed through to the quaking earth, where the thunder of their explosion was magnified in the close confines of the jungle thickets. Heavy machine guns—the dread “woodpeckers”—chopped through the trees, cleaving their own lanes of fire to tear at the defences…bombs and bullets crashed and rattled in an unceasing clamour that re-echoed from the affrighted hills…’36

All night, Japanese patrols probed the Australian lines. They tried to bayonet troops on the camp fringes and at least five Australians were wounded or killed by enemy bayonets that night. Scouts would cry out in English ‘Johnny! Johnny!’ Some taunts were lost in translation, such as, ‘You die! Good morning!’* Less amusing was the cold voice in the darkness, ‘You die tonight!’37

Combat was unbearably close. In one peculiarly harrowing incident, a Japanese soldier managed to slip a lasso made of vines around an Australian’s ankle, and tried to drag him into the jungle. ‘I had the presence of mind to fit my bayonet…stretch out and stab him in the eye and cut the vine rope,’ said the soldier.38

The Japanese preferred the worst conditions—moonless nights through driving rain—to attack. They used flares, and smoke candles, banged tins, and shouted ‘simply to keep us awake’, thought one Australian private. The Australians, however, learned to use the enemy’s noises against them by listening closely for the direction of the sound, often with deadly precision. One AIF soldier claimed to have lobbed a grenade into the horn of a bugle, silencing the bugler.39

The weird dirge heard at Kokoda often preceded a charge: ‘…a shouted order from the rear, echoed by subordinate commanders further forward, and then succeeded by a wave of noisy chattering…Then right along the front the final, urgent order rose…’40 There were loud cries of ‘Banzai!’—‘Long live the Emperor!’—the banging of tins, and the wail of bugles. (One Japanese ruse was to burst through a smoke cloud yelling, ‘Gas! Gas!’) Then ‘Nippon’s screaming warriors’ dashed towards the Australian lines.41

All day reckless waves of Japanese tore down Naro Ridge and into the Australian perimeter, ‘regardless of the casualties that soon cluttered that short stretch of open ground’.42 ‘They just kept coming,’ recalled Sergeant George Cops of the 39th. ‘You just could not stop them. A lot of us thought Moresby would fall.’43 The 39th were virtually overrun—251 out of 700 men were left—when a fresh batch of AIF troops, under Captain Claude Nye, rushed up to Front Creek, grabbing mortar bombs and grenades as they came. ‘I do not remember anything more heartening,’ said Honner, ‘than the sight of their confident deployment.’44

Fierce hand-to-hand fighting ensued, as Honner witnessed at Front Creek, and rendered in his scorching passage: ‘Through the widening breach poured another flood of the attackers…met with Bren gun and Tommy gun, with bayonet and grenade; but still they came, to close with the buffet of fist and boot and rifle-butt, the steel of crashing helmets and of straining, strangling fingers. In this vicious fighting, man-to-man and hand-to-hand, Merritt’s men were in imminent peril of annihilation.’45

The Australian light machine-gunners still held the line beyond which lay a rising pile of corpses. To their relief, a single bugle note would sound, and the attackers would melt back into the jungle (sometimes encountering stray Australians in sudden, shocked encounters in the darkness).*

A strange calm fell over the eastern flank on the 28th and 29th. The Japanese oddly faltered. They could easily have broken through from Abuari, destroyed Potts’s HQ and cut the Australian army in half. Instead, Horii diverted most of his eastern force across Eora Creek to attack Isurava village. His sudden change of plan remains ‘one of the mysteries of the Papuan campaign’.46 Perhaps he believed stronger enemy reinforcements had arrived at Abuari, than in fact had. Just two companies, under McGee and Sublet, were available; they crossed the waterfall and entered the village at sunset, unopposed.

A low mist shrouded the valley, and the air was heavy with moisture—perfect conditions for a Japanese charge. Later that evening, ‘amid wild yelling’, the Tsukamoto and Kuwada battalions rushed the Australian dugouts at Front Creek, in waves of a hundred at a time. The Australian Bren and Tommy guns chattered away as crowds of warriors fell before them. In one attack, an estimated 90 Japanese infantry were shot.

Potts’s situation reports on 29 August bear out his rising anxiety (his password to Port Moresby that day was, suitably, ‘FILTH’):

29 Aug 42

SITREP to 2100 hrs. ISURAVA. Front and left flank 2/14 Bn broken. Attempt to restore unsuccessful…Weak coy 53 Bn sent in support of 2/14 Bn. Unable to dislodge. 39 Bn effective strength down to 16 offrs 235 Ors. No amm[unition] at MYOLA. No droppings today. Shortage green uniforms lack of rifle grenades severe handicaps…Apparently enemy strongly reinforced last two days.47

General Horii had not expected such strong resistance. His planned five-day march to Port Moresby was already three days late. His officers were alarmed. Lieutenant Noda, of the Kuwada Battalion, wrote: ‘The Australians are gradually being outflanked, but their resistance is very strong, and our casualties are great. The outcome of the battle is very difficult to foresee.’ Some Japanese vented their frustration with startling bursts of suicidal violence. George Woodward, a Tommy gunner, remembers a Japanese officer charging down the track, waving his sword. The Australian Bren guns almost chopped him in half. The officer fell at Woodward’s feet, his binoculars dangling from his neck, and his sword stuck upright in the earth.

At sunset on the 29th the Japanese commander committed his men to an attack in full strength that would ‘shatter the Australian resistance beyond hope of recovery’.48 He called on no less than five Japanese battalions, including two fresh units of the Yazawa Butai (41st Regiment). The attack would start that night and continue the next day, across the whole breadth of the valley.

The Japanese commander’s progress report was precise:

The Nankai Shitai since 24th August have succeeded in completely surrounding the Australian forces…The annihilation of the Australians is near, but there are still some remnants…and their fighting spirit is extremely high.

The enemy’s defeated 39th battalion has been reinforced, and…they appear determined to put up a serious resistance. The Shitai will make night attacks and will be expected to capture the Australian positions…49

The Kusunose and Yazawa units were ordered up to execute the last Japanese offensive at Isurava.

It was a long night. It did not result in the Australians’ annihilation. At troop level, doubts were creeping in. Hirano noted in his diary, ‘enemy seems to have lost their fighting spirit’, but added, ‘Many of our number were killed or wounded.’ They included his old friend First Lieutenant Hatanaka Seizo with whom ‘only this morning I was gaily talking over a cup of sake from the canteen. Now it is only a memory. How cruel and miserable this life is!’50

The sun rose on two armies eating a brisk breakfast: a handful of rice for each Japanese soldier; bully beef for the Australians. The last battle for Isurava erupted at dawn on the 30th. It started with a Japanese diversion on the east flank, at Abuari, where a detachment of the Australian 2/16th Battalion moved to encircle a 100-strong Japanese force. Neither side gained ground, and the Australians suffered heavy casualties, not least from the Japanese ambush technique: ‘They climbed into the dense foliage of the trees and…attacked from all sides and on top—a terrifying experience.’51

The sources we have present a confused chronology of that day. We do know that the battle continued long into the night, along the whole front, from Abuari to Naro Ridge. But the precise order of events is difficult to confirm. No one on the ground knew exactly how the next section along was faring.

Signal lines were invariably faulty, or ‘being cut all the time’, recalled Phil Rhoden.52 Signalmen were constantly repairing the wires that linked forward troops with unit HQs. Major Geoffrey Lyon, among the first of the AIF troops up the track, recalled that the radios were useless. ‘Each man [was] totally reliant on the others, almost blind in the concealing grass.’53 So they resorted to runners, but these men took an hour through dense jungle to get across the main battle area, which was about 100 yards deep by 750 yards wide, Rhoden estimated.

Then the waves came. The Japanese charged all day, racing up to the Australian dugouts with bayonets fixed. All over the field, Australian machine-gunners and riflemen, amazed at the enemy’s willingness to die, kept firing. The Australian troops thought this madness, not bravery.

It was ‘like a brawl on a football field, things just got totally out of control’, said Rhoden.54 This brawl had guns and bayonets as well as fists. One AIF platoon55 repulsed ‘eleven enemy attacks, each of about company strength’ (i.e. about 120 men), inflicting 250 casualties.56

The Australians had neither the numbers nor the ammunition to withstand the onslaught. They were gradually overwhelmed, but not without a string of extraordinary last stands, which yielded more Allied decorations than in any other single battle in the Pacific.

These were not blind heroics; they were calculated initiatives by Australian privates, corporals and platoon commanders determined to hold off the enemy as their units withdrew. Thus Private Wakefield, a Sydney wool worker, held up a Japanese charge as his section fell back; he won the Military Medal. Thus Captain Maurice Treacy, a shop assistant, ‘parried every thrust levelled at him’.57 He got a Military Cross. Though wounded in the hand and foot, Corporal ‘Teddy’ Bear, a die-cast operator from Moonee Ponds, killed a reported ‘15 Japanese with his Bren gun at point blank range’; he was later awarded the Military Medal and the DCM.58 Lieutenant Mason, a draftsman, led his platoon in four counterattacks that afternoon; as did Lieutenant Butch Bissett, a jackaroo, whose platoon fought off fourteen Japanese charges.

At noon that day, the Japanese tried to run straight up the centre, towards the site of the present-day Isurava Memorial. It was an astonishingly audacious move, as anyone who has seen Isurava will acknowledge. The steep gradient shows why a few Australians were able to resist them for so long. By the early afternoon, ‘the breakthrough was menacing the whole battalion position’.59 A 2/14th HQ detachment rushed up to meet the emergency. Privates Alan Avery and Bruce Kingsbury latched onto this last attack.

Kingsbury was an average, outgoing young Australian of apparently modest ambitions. After leaving school, he took various jobs around New South Wales and Victoria—real estate salesman, station hand, farmer—before returning to work for his father’s property business in Melbourne. He enlisted in the AIF on 29 May 1940, and served in Syria and Egypt—then came home with the 7th Division to fight the Japanese. Avery and Kingsbury were childhood friends; they’d enlisted together, and maybe Avery best knew what ran through Kingsbury’s mind at that moment: Calculated courage? Conscious self-sacrifice? Or the thoughts of a young soldier anxious not to be seen to fail? Perhaps all three combined to produce Kingsbury’s next action, as recorded in his citation for the Victoria Cross, the Commonwealth’s highest military honour:

…one of few survivors of a Platoon which had been overrun and severely cut about by the enemy, [Kingsbury] immediately volunteered to join a different platoon which had been ordered to counterattack. He rushed forward firing the Bren gun from his hip through terrific machine-gun fire and succeeded in clearing a path through the enemy. Continuing to sweep enemy positions with his fire and inflicting an extremely high number of casualties…Private Kingsbury was then seen to fall to the ground shot dead by the bullet from a sniper hiding in the wood…60

He died instantly, aged 24. His was the first VC won on Australian soil. ‘Kingsbury’s Rock’ stands to the right of the Isurava Memorial, and a roadside rest area between Sydney and Canberra also bears his name.

VCs are not awarded for blind heroics; the action must tangibly improve the unit’s position. Kingsbury’s saved his battalion headquarters by halting the enemy advance. ‘He stabilised our position; he just made up his mind he was going to do it, and he did it,’ said Rhoden.61 If the Japanese had broken through they would’ve overrun and destroyed the Australians, and no doubt ‘streamed on down to Port Moresby’, said McAulay.62 His action inspired his mates to follow: Kingsbury’s section—ten men of the 2/14th Battalion—remain the most highly decorated in military history, winning a Victoria Cross, two Military Crosses, three Military Medals and several Mentions in Dispatches.

It was a brief respite. The Japanese kept surging up the mountain and down the sides of Naro Ridge. The Australian body count rose. In a day, C Company of 2/14th Battalion sustained dozens missing or dead. The death of Harold Bissett deeply saddened the battalion. He was a popular officer. Carried to safety by four volunteers—fighting off the enemy as they went—Bissett sustained severe abdominal wounds. He died at 4.00 a.m. on the 30th in his brother’s arms. ‘I held him in my arms for four hours,’ said Stan Bissett. ‘We just talked about our parents, and growing up, and…good things.’63

Among the last gestures of useful Australian defiance at Isurava was that of Corporal Charlie McCallum, a farmer of South Gippsland, Victoria. At the risk of sounding dangerously flippant, his action seemed more Schwarzenegger than Anzac. After the order came to pull out, he remained behind to cover his platoon. He sprayed the enemy with his Bren; when it ran out of ammunition, he swung up a Tommy gun grabbed from a dead mate. While he checked their advance with this weapon, he slammed a full magazine into the Bren with his right hand. When the Tommy ran out, he resumed firing with the Bren until his platoon were safe. He was wounded three times during this performance, in which he literally found himself firing amidst a crowd of Japanese troops so close that one, lunging forward as he died, tore off McCallum’s utility pouches. McCallum was reported to have killed 25 Japanese and saved his platoon. He was recommended for the Victoria Cross; he received a Distinguished Conduct Medal, and died in a later battle on the track.64

Japanese survivors remember that day as the defining battle of the Kokoda campaign. ‘For eight hours…the Australians offered fierce resistance without withdrawal, resorting to hand-to-hand combat. There were numerous point-blank hand grenade exchanges.’65

Yamasaki recalls that every officer in his company was killed or wounded. ‘The resistance was very strong. The Australian position was very good; they were high up. Even when men were killed, we had to keep going, to keep attacking in waves.’ He participated in a bayonet charge, and was hit in the wrist and hand by shrapnel: ‘My rifle was thrown ten metres away. I saw white flesh in my hand and I was ordered to go to the rear.’ He stayed a week in the Kokoda field hospital ‘with no morphine. It was extremely painful.’ Were the Japanese scared? ‘We were not scared at all, not of the jungle or the enemy. We were trained to attack—we were told if we didn’t attack we’d be killed.’

Shimada looked slightly incredulous when asked the same question: ‘We were never afraid,’ he said quietly. The idea was inconceivable to this 86-year-old warrant officer. However, Yamasaki remembers one man being so frightened he refused to fight; he was sent to the rear. ‘I brought him back when he had recovered his nerves.’66 He never informed the man’s superiors—cowardice was severely punished, often by execution.

In the late afternoon it started to pour with rain, and the flattened jungle became a steaming wasteland. The little bomb craters and weapon pits filled with water. Lanes of devastated vegetation lay in the spectral aftermath of concentrated machine-gun fire. Platoons all along the Australian lines were being infiltrated and overrun. Some ‘stood ringed by a scattered rampart of the enemy dead’.67 Some 250 Japanese corpses were later counted in front of Harold Bissett’s position.

In total the Japanese had lost 550 men killed, and more than a thousand wounded.68 The Australians lost about 250, with many hundreds wounded. The most depleted unit was the 2/14th Battalion, able to field only 230 men after Isurava, half its initial force.

The Australian survivors withdrew in a state of shock. The recapture of Kokoda a mere pipedream, Potts was now fighting to save his army. In despair he sent into battle about a hundred remaining troops of the 53rd, who’d been resting at Alola. They got no further than the Isurava Rest House where, ‘weary of the march’, they decided to rest.69 With no intention of advancing, some commandeered native carriers to help carry their weapons back to Port Moresby* Potts’s leadership could not undo the damage. The unit had imploded—physically and psychologically.

Their unfortunate experience sits uncomfortably alongside the incredible decision of 30 wounded men of the 39th Battalion, then sitting in Eora Creek (waiting to return to Port Moresby). All except three got up and stumbled back into battle. Lieutenant Stewart Johnston, a huge 24-year-old with a handlebar moustache, led this ‘weak and tottering cohort of the crippled and sick’ past the few 53rd survivors, then sitting ‘in peaceful unconcern by the track’.70 The three who didn’t go back were forgivably ‘minus a foot; had a bullet in the throat, and a forearm blown off’.71

So, too, the ghosts of troops thought lost or dead in the jungle returned in corporeal form to fight. One ‘grimy bearded figure’ saluted Honner and announced, ‘Sword, Sir, reporting in from patrol’. Sword’s platoons had been cut off behind enemy lines for three days. Their appearance prompted a corporal to observe, ‘It was enough to make a man weep to see those poor skinny bastards hobble in on their bleeding feet.’72 They too rejoined the battle.

However selfless and brave they were, Potts’s men were near-spent. The 2/16th Battalion summoned a last counterattack at Abuari, which failed. Perhaps fittingly, one Australian soldier, shot in the buttocks, dropped his trousers to inspect the wound and asked a mate, ‘Are you sure that’s blood?’

After some fierce fighting, with dozens killed, the Australians fell back to Eora Creek in disarray. Potts was forced to abandon 25,000 small arms bullets, 1500 Tommy gun rounds and 500 grenades at Alola.73

Rowell was clearly unaware of the disaster when he wired Blamey on 31 August:

To: Landops

31 August 42

From: NG Force

Personal for Commander in Chief from ROWELL:

…POTTS HAS FORCE WELL IN HAND AROUND ISURAVA AND I HAVE NO DOUBT AS TO HIS ABILITY TO CLEAR THE POSN. IT IS AS WELL THAT AIF TROOPS WERE SENT UP AS OTHERWISE I FEEL WE MIGHT HAVE BEEN PUSHED OFF THE RANGE…WE ARE EXERTING ALL OUR ENERGY TO MAINTAIN OFFENSIVE ACTION BUT YOU WILL APPRECIATE THAT ADMINISTRATIVE FAILURE WOULD BRING DISASTER.74

Potts disabused Rowell that evening, with his last two messages of the 31st:

31 Aug: 1215 Air strafing urgency requested ALOLA village…SITREP TO 1830 hrs. Force withdrawn on IORA CK area. 53 Bn MYOLA. 39 Bn approx 250, 2/14 Bn approx 230…holding posns vicinity IORA Ck…Enemy obviously in considerable strength…Still desire rest of 2/27 Bn.75

Thus ended one of the most bitterly fought infantry battles of the Pacific War. For the Japanese, it was a truly pyrrhic victory, won at great cost in terms of time, ammunition, supplies and lives. They were a week behind schedule. Isurava fatally wounded them, but the bleeding beast crashed on towards Port Moresby. The losses eclipsed Horii’s judgment. A defiant stubbornness now seemed to possess him and overrule his more sensible counsel. He intended to press his entire force over the mountains; his men cut a nine-foot mule track from Eora Creek in the direction of the main range to Myola. He drove them on into the depths of the Owen Stanleys, deaf to the howling reminder of every failed military excursion in history: a vastly overextended supply line.

The Australians had been ‘outfought and outmanoeuvred,’ according to an official report on Isurava. Their officer ranks were severely depleted. ‘Five platoon commanders died in those four days,’ concluded Rhoden.* ‘When they died, sergeants took over; when the sergeants died, corporals took over; and then the ordinary soldier. It was incredible. To this day I would do anything for the ordinary soldier.’76

What made Isurava uniquely wretched in the annals of war was the devastating closeness of combat. The armies were fighting within earshot and, unlike their medieval forebears, with guns and grenades. ‘When the Japs were about ten feet away…I shrivelled up into almost nothing,’ recalled one private. Near the end of the Pacific War a US army medical team examined the effects of near point-blank fighting in jungle conditions. It found that more than 50 per cent of the casualties were struck at 25 yards or less, and nearly 85 per cent at 50 yards or less.77 The wounds inflicted by a high velocity bullet at this distance can be imagined. Abdominal injuries were always fatal; shattered knees and limbs left the victim stranded. There were no helicopters. Hand-to-hand combat with fixed bayonets made the battle seem like ‘a knife fight out of the Stone Age’.78

Smoky Howson was haunted for the rest of his life by the sight of a Japanese soldier ‘with both legs chopped off from the trunk of his body’ by machine-gun fire. Ordered to ‘finish off the dying Nip’, Howson hesitated. He noticed that the man’s eyes were still open. ‘He had a terrified expression and he was still moaning, and I have lived to this day with those eyes staring at me.’79 Howson said this in an interview on 23 March 2003, a few months before he died, aged 85.

The Australian nightmare was just beginning. Potts somehow had to stop the rampaging Japanese army from reaching Port Moresby. Another question was extremely vexing for this brigadier who concerned himself so much with his men: How, Potts wondered, were the sick and wounded to survive?