No Chinese dwelling type is better known than the “courtyard house” or siheyuan, in which at least one courtyard is enclosed within four surrounding single-story buildings that face inward towards the open space. Quadrangular courtyard structures have been common architectural forms for houses, palaces, and temples in China since at least the Western Zhou period between the eleventh and tenth centuries BCE, fundamental units in the gridded urban fabric of cities in northern China.

Prototypical siheyuan are associated with Beijing and neighboring areas where they are found in many configurations, some quite simple but more of them rather complex in terms of layout. Among the near canonical elements of siheyuan are enclosure behind high gray walls with only a single off-center entry gate, which affords substantial seclusion; orientation to the cardinal directions with main structures facing south or southeast; balanced side-to-side symmetry of the dwelling complex, and a hierarchical organization of space along a clear axis. Moreover, strictly observed sumptuary regulations during the Ming and Qing dynasties in the imperial capital regulated the overall scale of siheyuan, including dimensions of timbers and widths of halls, as well as colors and other ornamentation, even types of furniture. As a result, the residences of ranked individuals and princes were clearly differentiated from merchants, who conceivably could have built large siheyuan, and of course those of common people.

Within the massive walls of the Purple Forbidden City, the cosmic center of the empire, are three parallel axes, along which are aligned the grand imperial palaces as well as the walled residences of the imperial family and their numerous retainers, including some 1500 eunuchs in the later Qing period. Along the westernmost axis in the Forbidden City’s northwest quadrant, high walls enclose human-scale courtyards as the private apartments for emperors, their wives, and families. Although embellished with fine carpentry, sumptuous colors, and ornate furniture, these interconnected siheyuan are in plan and structure courtyard residences, which to some degree are similar to the layouts of even temples found throughout urban and rural China.

Before 1949, the Purple Forbidden City, which is still walled, was surrounded by a larger walled enclosure called the Imperial City, beyond which was another large area bounded by the actual city walls of Beijing. Walls within walls within walls created a nested structure of ceremonial, residential, and commercial spaces—somewhat like cells—of enormous cosmological and practical significance. With streets and lanes running east to west being crossed by those running north to south, much of Beijing was laid out like a chessboard beginning in the Yuan dynasty when the city was called Dadu. Well-defined neighborhoods developed along the veins of the city. These veins in Beijing are called hutong, narrow lanes and alleys that are said to be “like ox hair” in that their number is beyond being able to be calculated (see page 24). Here, in these hutong neighborhoods, princes, court officials, scholars, merchants, craftsmen, and others built densely packed single-storied siheyuan of many sizes, some with only a single courtyard while others had several or many linked together.

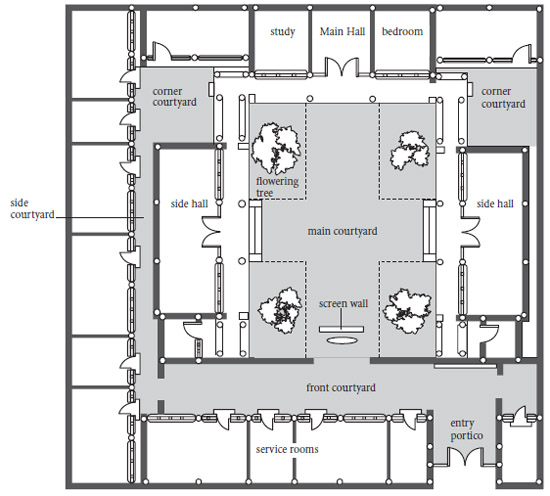

Perspective view of Mei Lanfang’s residence in Beijing. At its simplest, a siheyuan is quadrangular in plan and surrounded by a wall with only a single entry gate.

Both the roof overhang and the brackets under the eaves of the Main Hall are colorfully ornamented with auspicious motifs.

Some siheyuan were sprawling manors while others were crowded with several families. Princess Der Ling, First Lady in Waiting to the Empress Dowager Ci Xi who married an American in 1907 and became Mrs Thaddeus C. White, wrote, “The houses in Peking are built in a very rambling fashion, covering a large amount of ground, and our former house was no exception to the rule. It had sixteen small houses, one story high, containing about 175 rooms, arranged in quadrangles facing the courtyard, which went to make up the whole; and so placed, that without having to actually go out of doors, you could go from one to the other by verandas built along the front and enclosed in glass. My reader will wonder what possible use we could make of all of these rooms; but what with our large family, numerous secretaries, Chinese writers, messengers, servants, mafoos (coachmen), and chair coolies, it was not a difficult task to use them.

“The gardens surrounding the houses were arranged in the Chinese way, with small lakes, stocked with gold fish, and in which the beautiful lotus flower grew; crossed by bridges; large weeping willows along the banks; and many different varieties of flowers in prettily arranged flower beds, running along winding paths, which wound in and out between the lakes.”

Manors of this type are essentially now extinct, having been carved up to meet the requirements of many families or torn down to accommodate modern needs. Just to the north of the Imperial City walls and adjacent to Qian Hai Lake, however, is a fine extant example. Known as Prince Gong’s manor, and called in Chinese “Gong Wang Fu,” the expansive dwelling complex reveals the seemingly complicated relationships of late Qing imperial times. Prince Gong, the brother of the eighth emperor Xianfeng who reigned from 1851 to 1861, moved into this imperial residence in 1852, occupying spaces that were built probably a century before. Prince Gong was also the sixth son of Guangxu, the ninth emperor of the Qing dynasty who reigned from 1875 to 1908 and the father of China’s last emperor, Pu Yi. An extensive and splendid residence with three major building complexes, his manor is known especially for its garden buildings and gardens, including a labyrinth of rockeries, a teahouse, and performance spaces. Some claim that the celebrated author Cao Xueqin gained inspiration while living in Prince Gong’s mansion as he wrote Hongloumeng, known in English as A Dream of Red Mansions.

Early in the Qing dynasty, there were eight major prince’s manors or mansions, a number that was increased to twelve by the end of the dynasty. Except for Prince Gong’s mansion, none of the others remains reasonably intact, all now having lost the grace that once characterized them and indeed even much of their original form. Over time, both in the early twentieth century and especially after 1949, government offices, hospitals, schools, arts organizations, factories, and various enterprises came to occupy them, in the process transforming once sumptuous residences into utilitarian spaces. The Ministry of Interior, for example, occupies the site of Prince Li’s mansion south of Xi’anmen and Prince Rui’s mansion in the Nanchizi area, built in the early Qing dynasty, has been the location for different schools over many years. Prince Yu’s mansion in the Dongdan area was transformed for use by the Rockefeller Foundation’s Peking Union Medical College in 1917, and is now the location for Beijing Hospital.

Mei Lanfang’s Siheyuan

Located along Huguosi hutong, a quiet lane in the Shichahai neighborhood in the Western District of Beijing, is a gray brick siheyuan today known as the former residence of Mei Lanfang (1894–1961), the celebrated actor of Jingju opera, sometimes called Beijing or Peking opera. Mei Lanfang lived in the courtyard house only during the last decade of his life from 1951 to 1961. During the latter part of the nineteenth century, the courtyard was but one part of a much larger mansion of an imperial prince of the Qing dynasty, one nonetheless that was much smaller and less grand than those of other Qing nobility.

Mei Lanfang began to study Chinese opera at the age of eight, gaining an early national reputation. His tours to Japan in 1919 and 1924, the US in 1930, and the USSR in 1932 and 1935 brought his talents playing female roles before international audiences. Soon after 1949, Zhou Enlai urged Mei Lanfang to return to Beijing and serve as president of the Institute of Chinese Opera, even promising that Mei and his family could return to the old siheyuan courtyard they had purchased in 1921 and occupied prior to selling it in 1933 during the Japanese occupation of China. Mei Lanfang, however, was reluctant to reclaim a residence he had once sold, declining the offer, even though he had described it in his autobiography as simply an “ordinary courtyard house.”

Set upon a prominent stone base and surmounted by an imposing superstructure, the marble basin is said to have been obtained from an imperial palace. On its right is the patterned screen wall.

The symmetrical and hierarchical organization of a siheyuan is clearly shown in plan view, although in this case the outer row of rooms on the west side alters its symmetry.

Facing south on the northern side of the courtyard and usually only three bays in width, the Main Hall or zhengfang of most siheyuan is a low single-story building. Dominant in this courtyard is a pair of persimmon trees. In summer, tables and chairs from adjacent rooms would be moved into the courtyard so that family members and guests could enjoy sunny days and quiet evenings.

The central room of a zheng-fang traditionally was the location for the ancestral hall and the center for family ceremonies and celebrations. Here, in Mei Lanfang’s home, this central space was used as a drawing room, an intimate space to entertain close friends.

He nonetheless accepted the proposal of a gated structure on Huguosi hutong, which was of course only a fragment of a complete dwelling, a derelict structure that had not been maintained well for many years. At the time, only the main northern structure, which faced south, and the two facing perpendicular wings stood. In time, an outer courtyard and a side courtyard with associated buildings were built to give shape to the integrated siheyuan quadrangular residence still seen today. With a total area of 716 square meters and about 500 square meters of floor space, the completed structure is a mid-sized siheyuan facing inwards rather than outwards and somewhat larger than his earlier residence. It has a rather conventional layout comprised of a series of gates, open spaces, and independent structures that create a sequence of graduated privacy, of increasing intimacy as one moves from “outside” to “inside.”

Along the southeast portion of the outer wall, the single entryway, with its pair of large leaves painted red, provides a rather plain threshold into a vestibule marked by a light gray brick spirit wall with bamboo planted in front of it. Turning left leads through another gate into a “public” zone, comprising a narrow rectangular open area that was used for the workaday activities of servants, a place for visitors to wait while they were announced, and a storage area for bicycles, briquettes for cooking, among many of the items used in a busy household. A pair of large deciduous parasol trees, with lobate leaves and racemes of tan-yellow flowers, spread their branches over the narrow courtyard. On the south side of the courtyard is a north-facing building called a daozuo, or “rear facing” structure, and on its right a wall with a splendid gate, called a chuihuamen or “festooned gate,” which mediates between the outer peripheral courtyard and the inner central courtyard. In addition to offering security for the interior precincts, this magnificent gate is also a focal point of interior and exterior ornamentation. A “festooned gate,” unlike the main entry gate along the lane outside, is usually highly decorated, with piled wooden structures and abundant ornamental design, but that of the Mei quadrangle is more serene. A visitor reaching this gate must climb several steps before entering the main courtyard, the view of which is blocked by a patterned screen wall or yingbi, set upon a prominent stone base and surmounted by an imposing superstructure. A marble basin, said to have been obtained from an imperial palace, was added as a decorative feature during Mei’s occupancy of the residence but is not a common feature.

The large central courtyard as well as the rectangular one at the entry and another slender one flanking a row of guest rooms on the west side of the residence represent more than 40 percent of the total ground area of this siheyuan. From within the interior courtyard, which is paved with square bricks and serves as the center of family life, the sky appears to reach to distant horizons unobstructed either by the dwelling itself or by neighboring buildings, all of which are low as well. As with other siheyuan in Beijing, trees and potted shrubs soften the architecture of the courtyard. Careful thought was given to plantings in order to insure pleasure during all seasons, not only in terms of vegetation but also bearing edible fruit and having auspicious connotations. Dominant in this courtyard is a pair of persimmon trees, producing a yellowish fruit somewhat plum-like with a flat appearance that is rather harsh and astringent until it has been exposed to frost and becomes palatable and nutritious. Matching these is a pair of flowering trees, an apple tree and a crab apple tree, planted, it is said, because the sound of all the tree names uttered together in Chinese— shishi ping’an — represent the homophonic invocation “always safe.” Persimmon and apple trees, moreover, live long, provide shade, and welcome birds. Pomegranates and jujube date trees, especially, because of their abundant seeds and rich symbolism are also favored as trees in siheyuan. On the other hand, evergreen pines and cypress trees as well as poplars are not common in Beijing quadrangles because they are believed most appropriate for gravesites. Tables and chairs from adjacent rooms are usually moved into the courtyard for family members and their guests to enjoy sunny days and quiet evenings. In the partially enclosed areas at the corner where the main building and side buildings nearly come together, flowering wisteria climb the wooden arbors that link them.

Lacquered lattice door panels, fitted with glass and silk curtains, separate the drawing room from a family sitting room.

On the west side of the drawing room is a large bright study, which is illuminated through the south-facing wall of windows.

The Main Hall or zhengfang, as with other classical siheyuan, is a low single-story building on the northern side of the courtyard and faces south, following the siting axiom zuobei chaonan, meaning “sitting north and facing south.” In this inner sanctum is the location for the Ancestral Hall and center for ceremonies as well as the residence for the household’s senior generation. Mei Lanfang used the central room as a drawing room, an intimate space to entertain close friends. On its east side is another family space, a parlor, which then leads to a bedroom. On the west side is a large bright study.

Perpendicular to the main structure is a pair of flanking buildings, one facing east and the other west with rigid bilateral symmetry, which served together as living space for married sons and their families. Beyond the western building and entered from both the first and second courtyards, is a rather uncommon feature, a long structure with numerous guest and storage rooms built into it.

An important element of Beijing siheyuan is the set of narrow covered verandas that serve as all-weather passageways around the courtyards. Because the surrounding individual buildings are structurally separate, each side of the quadrangle is entered and exited through a door facing the focal courtyard. Since no doorways interconnect any of the adjacent buildings that comprise the courtyard complex, movement between buildings is most direct across the courtyard during fine weather. The encircling narrow verandah under the eaves offers some limited protection during times of inclement weather, whether rain or snow, and the broad overhanging eaves and stout red-lacquered columns help to buffer the blustery winds and trap the sun’s heat during the course of a cold winter’s day.

As a celebrated performing artist, Mei Lanfang entertained numerous luminaries during his residence in this siheyuan. Fitted with a mixture of Chinese and Western furniture and fixtures, the house blended elements of the past with modern elements.

After Mei Lanfang died in 1961, his sons continued to live in the house even as his wife moved to a smaller residence. Soon after the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in 1966, however, Red Guards in Beijing regularly pasted posters on the exterior walls and gate criticizing Mei Lanfang’s bourgeois life. These actions led even his adult children to abandon the siheyuan, which then remained shuttered until October 1986 when the residence was opened as a museum. Subsequent visitation was light but has increased especially since the centenary of Mei Lanfang’s birth in 1994. Domestic and foreign visitors are not only interested in catching glimpses of what life might have been like in quiet siheyuan along the narrow alleys that once defined Beijing but also are curious about the life of one of China’s most prominent twentieth-century performing artists.

Mei Lanfang quotation:

“Small as the stage is, a few steps will bring you far beyond heaven.”

Siheyuan: Threats and Revitalization

During difficult times over the centuries, many families came to share courtyard spaces that once were elegant, reducing in the process their charm and quietude. Lao She, the playwright and author of humorous, satiric stories, wrote in his 1936 classic novel Camel Xiangzi about an industrious rickshaw puller and his life in the hutong and siheyuan throughout decaying Beijing. Concerning one courtyard and those who occupied it, he wrote: “There were seven or eight families living in their tenement courtyard, most of them crowded, seven to eight, old and young, into one room. Among them were rickshaw pullers, peddlers, policemen and servants. Each went about his or her job with never a moment to spare. Even the children went off with small baskets to fetch rice gruel in the morning and to scrounge for cinders in the afternoon. Only the very youngest remained in the courtyard, tussling and playing, their little bottoms frozen bright red in their split pants. Ashes, dust and slops were all tipped into the yard, which no one bothered to sweep. The middle of it was a sheet of ice which the older children used as a skating rink when they came back from scrounging cinders, shouting loudly as they slipped and slid about. The worst off were the old folk and women. Hungry and threadbare, the old people lay on icy cold brick-beds, waiting anxiously for the pittance the able-bodied ones earned to buy them a bowl of gruel.”

Even as prosperity returned after 1949, it became increasingly common for courtyard houses in Beijing to be shared by many unrelated families rather than continuing as private dwellings for extended families. While conditions rarely were as hard as described by Lao She, the city’s socialist bureaucratic housing allocation system gradually led to larger numbers of Beijing families living together in courtyard dwellings where they divided up once-commodious spaces into their own residential areas. As a result, the escalating use of limited space by larger numbers of people as well as inattention to repair brought with it general dilapidation that continued well into the early 1980s. Throughout the city, the infilling of courtyards with “temporary” kitchens, bedrooms, and storage sheds over time obliterated what had been the essential core of any siheyuan, the courtyard itself.

Mei Lanfang, husband and father, is here shown attired in the stage dress of a young woman, the only roles he played in Beijing opera.

Over the past quarter century, high-rise apartment buildings have created new living opportunities for city residents and reduced pressures on old single-story dwellings. However, as the city is modernized and developed, new challenges have emerged regarding the conservation and preservation of the architectural soul of China’s most impressive historical imperial capital. The razing of old hutong neighborhoods accelerated in the late 1990s, reaching alarming proportions after 2000 as demolition reached new heights. After two decades of sweeping destruction of hutong neighborhoods, less than a thousand siheyuan have been designated for preservation and saved from summary destruction. Even well-preserved courtyards that seem safe because of being listed for preservation have been summarily demolished, to the dismay of residents and preservationists.

Some old siheyuan have been salvaged, with all current residents relocated to new apartments, in order to meet the needs of wealthy and often well-connected individuals who wish to live in the city center in a style that is an improvement over past luxury. As a result, a luxury market has emerged in the districts around the old Imperial City, leading to gentrification and the fraying of the architectural fabric of old neighborhoods as rehabilitated siheyuan have been transformed into private estates, sometimes simply investment properties, with all of the conveniences of modern life, including automobile garages, air conditioning, modern kitchens and baths, security systems, and satellite antennas. In some cases, development companies, whose real estate arms build new villa-type courtyard residences that are multistoried, have demolished extensive areas in the city. A good example is Nanchizi, an area just outside the crimson walls of the Forbidden City, where a new term was invented— sihelou, meaning multistoried courtyard structures—to cloak the real estate venture with some of the historical resonance of the old word siheyuan. Touting the fact that two-story sihelou “follow” traditional old-style courtyard designs with their gray walls and open spaces, developers have produced designs similar to garden-style residences seen elsewhere in the world, embellished with traces of their Chinese patrimony in the form of mock-tile roofs (made of cement) and moon gates. Indeed, traditional siheyuan courtyard houses and hutong neighborhoods in Beijing have undergone a radical evolution as socialist economic and social policies have themselves undergone revolutionary change.

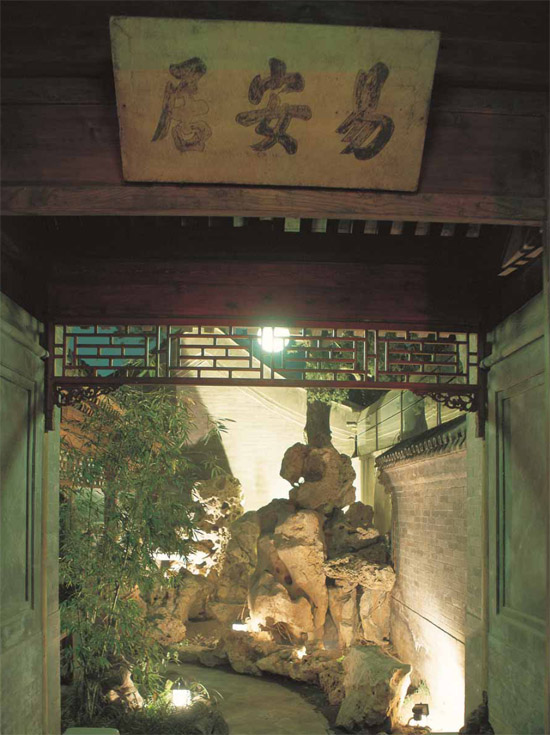

Viewed from a corner garden, replete with odd rocks, is a side building in a restored siheyuan.

The components of this restored siheyuan were moved from another area of Beijing while some of the decorative elements came from elsewhere. The intricately carved door panel showing four dragons was brought from neighboring Shanxi province.

Framed with decorative lattice and illuminated at night, this small side yard in a renovated Beijing siheyuan provides a space for exhibiting odd-shaped rockery. The three characters translate as “Abode of Tranquility.”

Other siheyuan that otherwise would have been demolished because of rising real estate values have been saved because they once were the residences of prominent persons or were occupied by party and government officials. In many of these courtyard houses, writers, academics, artists, political figures, and others lived much or part of their lives, enjoying the ambience of traditional courtyard life. Although some of these structures today ostensibly serve as museums, visitors can experience reasonably authentic Beijing siheyuan if they visit them even if one has little knowledge of the famous person who once lived there. Among the most interesting are those of twentieth century writers. Lao She acquired his Beijing courtyard home in 1949 when he returned from the United States and lived there until he died thirteen years later. One can only wonder if he ever considered what it would have been like to share it with seven or eight families. Lu Xun, the father of modern Chinese literature, lived in his single courtyard home beginning in 1923 but only for a little more than two years. Elsewhere in China, there are many former homes of Lu Xun, but none of them is a traditional courtyard house. Guo Moruo, a poet and dramatist born in Sichuan, lived in a Beijing siheyuan, which once was an annex of Prince Gong’s mansion, from 1963 until his death in 1978. An oddity of his residence is the presence of an extensive grassy courtyard planted with gingko and pine trees. Other lesser known historical figures whose residences are worth visiting include the eighteenth-century Qing-dynasty scholar Ji Yun’s Yuewei Cottage and the late Qing reformer Tan Sitong’s home that once was a guildhall.

Large numbers of similar old siheyuan residences throughout the city were allocated to important governmental functionaries after 1949. One, with a rich history, is now open. Along the tranquil Back Lakes area is Prince Chun’s extensive garden and house in which China’s last emperor Pu Yi was born. A home was created in this space for Madame Soong Qingling, the widow of Sun Yatsen, who occupied the gardens and a newly constructed “mansion” between 1963 and 1981. However, most of the old siheyuan today remain hidden behind high gray brick walls, their presence only known to aging neighbors.

This small gate into a modest siheyuan reveals some of the damage done during the Cultural Revolution, including the lingering two characters ge and ming, together meaning “revolution,” that were painted above the door at least a quarter century ago.

At the entryway of a Beijing siheyuan, a pair of lions sometimes stands sentry.

Whether the dwelling behind this old gate has been restored or remains dilapidated remains a mystery.