The houses within which Chinese families live their lives encompass a remarkable variety of styles. Until recent years, most Chinese dwellings were small, rather ordinary rectangular cottages, many mere huts, but there always have been significant numbers of expansive courtyard residences, as well as sometimes-grand manor complexes, and even sumptuous palaces, that are all in one way or other Chinese houses. While there is no single building style that can be called “Chinese,” thus no “typical Chinese house,” Chinese dwellings generally share a number of conventional features.Some of these architectural features—once thought to be universal and unchanging—have ceased to exist over the past quarter century as new ideas and new building materials have brought a striking transformation of housing throughout urban and rural China. While the predominance of traditional dwellings and local styles has been eclipsed in many ways by new housing styles, there is still much to be learned by looking at and appreciating examples of fine Chinese houses built in the past that even now are still found all over the country. Today, housing forms that break with tradition are common throughout China, yet dwellings continue to be built as they have for centuries by those without the means or inclination to build a “modern” dwelling.

Many, perhaps even most, old Chinese houses still seen today in villages, towns, and cities are rather unexceptional, nondescript, and thus ordinary, reflecting in part the fact that they were built of impermanent, easily accessible materials such as soil and plant materials that deteriorated over time. Many old houses remain standing, however often in dilapidated condition, among larger numbers of newer villa-style houses built of modern materials such as cement and tile. Yet, throughout China many old houses can still be visited that are grand in scale, sometimes even exquisite in terms of their proportions, constructed as they are of durable building materials, including fired bricks, rare timbers, and cut stone. Many of these are graced with skillfully crafted ornamentation—carved wood, stone, and clay—most of which evoke rich meanings that are sadly lost on most contemporary viewers. It is a selection of these fine examples of Chinese houses built over the past 500 years that are featured in this book. Together,they represent a personal and limited selection of some of my favorite Chinese houses culled from visits to literally thousands of Chinese dwellings over the past forty years. To do justice to China’s domestic architectural patrimony would lead to a book many times larger than this one.

Although it is possible to note similarities and differences regarding Chinese houses, it is not possible to understand variations and changes clearly over the sweep of Chinese history because of insufficient textual, archaeological, and visual evidence. Specialists, unfortunately,are not yet able to determine, for example, how a particular building form, floor plan, or structural element evolved historically or how any particular aspect came to be spread across China’s vast territory. Yet, it is certain that the weight of precedence and pragmatism arising from practical experience as well as the widespread use of conventionalized building elements all contributed to a conservative Chinese building tradition. Indeed, building forms that took shape thousands of years ago have had a remarkable resilience down to the present. On the other hand, there is significant visual evidence, observable today, of striking variations in architectural styles that are geographical—that is, varying over space—rather than the more elusive historical, varying over time. These geographical disparities reflect often practical responses to differing regional environmental conditions, underscoring the adaptability of traditional building forms and building practices under varying conditions.

In the Kang family manor in Henan province, some rooms are dug as caves into the loessial hill slope. This room serves as the shrine for the Three Living Gods of Wealth.

Strong local or regional idioms are characteristic of houses throughout China, so that it is proper to view Chinese dwellings as “vernacular architecture,” common forms whose variations are as diverse as vernacular languages and other aspects of everyday culture. Houses, indeed, are among the most lasting of all cultural artifacts, even though the materials of which they are made may decay or disintegrate, and the circumstances leading to their creation have passed. Dwellings take shape over time, sometimes growing and at others retrenching, but at all times suggestive of the internal as well as external dynamics giving them shape. Houses sometimes take shape over a long period of time, reflecting the ideas of successive generations and their changing abilities to shoulder the substantial costs associated with ongoing construction and the maintenance of what has been completed.

Old houses in China are not the product of a motionless traditional culture in which building forms were stagnant. Indeed, the rather simple terms “tradition” and “traditional” are in reality loaded with the ambiguities of agelessness, monotony, and permanence, and must be used carefully when describing old Chinese houses. The geographer Yi-Fu Tuan invites readers to ponder: “When we say of a building that it is traditional, do we intend approval or, on the contrary, criticism? Why is it that the word ‘traditional’ can evoke, on the one hand, a feeling of the real and the authentic and hence some quality to be desired, but, on the other hand, a sense of limitation—of a deficiency in boldness and originality?” (1989: 27). In fact, the notion of “tradition” is rooted in the literal meaning of “that which is handed down,” an often robustly dynamic process whatever its pace, that has bequeathed buildings which are often original and bold while sometimes displaying deficiencies and incongruities as well as utilitarian and attractive formulaic elements.

No purpose is served in searching for a simple, single explanation about why Chinese houses generally were as they were in the past or even why one house in one place differs from another in another place. While it is oftentimes facile to see common patterns that only differ in details, it is important to recognize as well a significant heterogeneity of forms and explanations relating to houses as well as the settlements within which they are found (Ho, 2001).

Many of us who study Chinese houses have moved away from looking at dwellings with mere buildings as the units of analysis. Each house is a home for a family that exists in both time and space, a dynamic entity that manifests not only the family within it in its varying evolving forms, but as well is a constituent part of the place in which it is located.

“Su Shi's Second Poem on the Red Cliff” (ink on paper), completed by Qiao Zhong-chang during the Northern Song dynasty (1123), depicts Su Shi’s experience while jaunting with friends in the wild landscape surrounding his place of exile, as recounted in his poem. In the scene reproduced above, Su says goodbye to his wife before setting off from his farm-stead, which the painting shows as a compact courtyard dwelling wrapped with an outer wall. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri.

Like any building, a house protects those inside from the vagaries of weather—heat and cold, rain and snow, humidity, and wind—yet “sheltering” is only one of the factors contributing to house form. Every dwelling is constructed within a broader environmental context—climate, that is, the long-term conditions of weather, as well as soils, rock, and available vegetation—that is often well understood by local inhabitants, who—because of pragmatic habits and environmental sensibilities—build their dwellings in order to provide a level of physical comfort, a habitable internal microclimate. In China and nearby areas of East Asia, this attentiveness to environmental conditions is significantly amplified because of the application of fengshui (“wind and water”), or geomancy, which has at its base a sensitivity to recurring patterns of nature and a generally heightened level of environmental awareness.

As compelling as are the varying responses to environmental conditions, dwellings, however, are more than mere refuges from the extremes of weather, havens from the changing forces of nature. Chinese housing forms may have similarities, but each is created under local conditions. Whether small or large, it seems that any Chinese house is in a continuous state of alteration in order to meet the ongoing life cycle changes and often irregular requirements of a family: a marriage of a son brings a new woman into the house and the formation of a conjugal unit; a marriage of a daughter leads to her abandoning her old room and attenuating long-held family relationships as she leaves her parents’ home; new family members are born and others die; relatives come for lengthy stays; and rooms are sometimes rented out to others as a family’s needs require. New cooking stoves are added to accommodate some of these changes, even as doors are sealed or opened and ritual spaces redefined.

Rural as well as urban houses serve as the essential stages for each household’s production and consumption activities and reflect elements of their religious and cosmological beliefs, in addition to expressing at least some aspects of the often complicated patterns of personal relationships of the household in terms of age, gender, and generational status. Examples of these dynamic elements are portrayed in many of the examples discussed and illustrated in the pages that follow.

Chinese Houses: Similarities and Differences

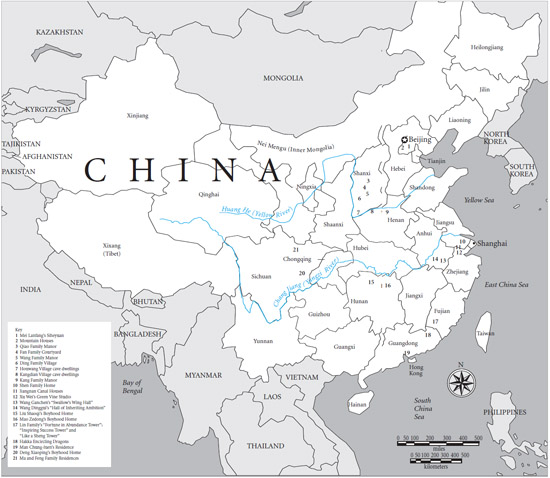

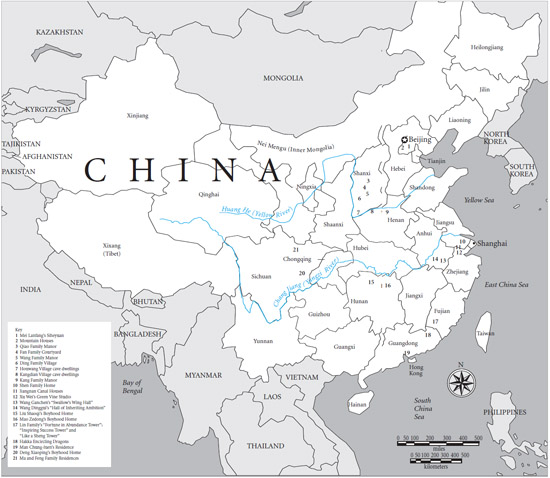

With land area approximately the same as that of the United States and twice that of Europe, as well as widely varying climatic conditions, China includes fifty-six disparate nationalities and a remarkable diversity even among its dominant Han ethnic majority. It is thus not surprising that Chinese houses are at least as varied as those found in multinational Europe and are more diverse than those in the United States. Rather straightforward and simple I-shaped houses, often with peculiar local characteristics, are ubiquitous throughout China. Less well known, however, are the many larger, quite distinctive housing types of remarkable complexity that complement the relatively uncomplicated rectangular houses, and underscore the richness of China’s housing traditions. These larger structures include hierarchically organized quadrangular courtyard residences in the Beijing area, unique below-ground cave-like dwellings in the north and northwest, expansive manor-complexes in the north, extraordinarily beautiful two- and three-story merchant dwellings in central China, massive multistoried fortresses in the hilly south, portable tents and cantilevered pile-dwellings occupied by ethnic minority populations, as well as boats of many types along the coast and embayed rivers. Each of these will be represented in the sections that follow.

While there is no single style that can be called “a Chinese house” across time and space, it is possible to point to a set of remarkably similar elements shared by many—if not most—houses, whether simple or grand. Chinese builders throughout the country historically favored a number of conventional building plans and structural principles. In addition, special attention was paid to the environmental conditions of specific building sites and to manipulating building parts in order to acquire some control of natural conditions, including access to sunlight and prevailing winds in addition to blocking cold winds and collecting rainwater. Rooted deeply in Chinese building traditions, these fundamental building rudiments have influenced as well the building traditions found in Japan, Korea, and to some degree Vietnam (Balderstone and Logan, 2003; Ho, 2003; Lee, 2003; Matsuda, 2003; Ruan, 2003; Steinhardt et al., 2002).

Published in 1911, this is among the first photographs of a round “clan house” rampart on a hilltop in southwestern Fujian. Strangely, unique structures of this type were not further photographed or even noted for nearly a half century after.

Zhen Cheng Lou, a massive structure built in 1912 in Hongkeng village, Fujian, is a four-story circular fortified structure with windows only on two levels of the upper wall.

Mixed among structures of various shapes in a village in southwestern Fujian province, the large circular structures appear like landed UFOs.

Open Spaces: Courtyards and Skywells

Chinese builders not only create structures—space that is enclosed with walls and a roof—but also recognize the need to create exposed spaces for living, work, and leisure. Open spaces, often loosely referred to as “courtyards,” are an important category in the spatial layout of any fully formed Chinese house. They are found in seemingly endless variations, in relatively tiny houses as well as in complicated, expansive ones in which enclosed open spaces even include within them other buildings surrounding open spaces. Archaeological evidence shows that courtyards, a negative space, were elements of Chinese structures as early as 3000 years ago, and continued to be a fundamental design principle of temples and palaces, in addition to houses, down through the ages.

In “composing a house,” to use Nelson Wu’s apt phrase, open spaces are part of a “house–yard” complex. “The student of Chinese architecture,” he continues, “will miss the point if he does not focus his attention on the space and the impalpable relationships between members of this complex, but, rather, fixes his eyes on the solids of the building alone” (Wu, 1963: 32). It is important, of course, to recall that the “solids of the building” themselves are spaces, created by the structure. The Dao De Jing, a fourth-century BCE work attributed to Laozi, anticipated the significance of voids, of apparent emptiness: “We put thirty spokes together and call it a wheel; But it is on the space where there is nothing that the usefulness of the wheel depends. We turn clay to make a vessel; But it is on the space where there is nothing that the usefulness of the vessel depends. We pierce doors and windows to make a house; And it is on these spaces where there is nothing that the usefulness of the house depends. Therefore just as we take advantage of what is, we should recognize the usefulness of what is not” (Waley, 1958: 155).

At least one open space is an important element of any Chinese house, even when the space is merely the outdoors immediately in front of a rectangular structure and without surrounding structures. Adjacent to most courtyards on at least two and often four sides are the buildings, positive constructed spaces. Full enclosure with buildings on three sides— an inverted U-shape—is quite common throughout China. Sometimes the fourth side is defined by a wall, which from the outside may make it appear as if the dwelling is wrapped by structures on four sides when this is not, in fact, the case.

Compact siheyuan or quadrangular courtyard houses of this type are found in villages, such as Chuandixia, in the mountainous areas around Beijing municipality.

Shown in this rubbing is an upper-class residence built some 2000 years ago. The complex comprises multiple courtyards surrounded by flanking structures and watchtowers. Yinan county, Shandong.

The common English term “courtyard” itself, or even its many Chinese language equivalents, is insufficient in differentiating the many types of open spaces seen from place to place in China. Still, there are a number of principles even if there is inconsistency in how terms are used. In general, the proportion of open space to enclosed space is significantly less in southeast and southwest China as compared to the north and northeast. In northeastern and northern China, courtyards are comparatively broad while in southern China they are usually condensed in size, sometimes becoming a mere shaft of open space. The Chinese term tianjing, translated as “sky-well,” catches well the meaning of constricted southern “courtyards,” especially in two- or three-story dwellings where their verticality accentuates their diminished horizontal dimensions. Yet, in some parts of southern China, these small openings are still referred to as “courtyards.”

Climatic variables play critical roles in differentiating the proportions of enclosed structures, transitional spaces, and open spaces. In the dry, colder areas of north and northeastern China, open spaces are generous portions of the house–courtyard complex, with the ratio decreasing as one moves south. Attention is paid to blocking cold winter winds and increasing the receipt of winter sunshine by eliminating windows and doors on back and side walls. Throughout central China, where winters are mild and summers hot, transitional spaces, such as verandahs and rooms with open-faced lattice door panels, increase in extent, while open spaces generally decrease in proportion to enclosed spaces. In the hot and humid areas of southeastern China, open spaces—here usually only skywells—shrink in size while transitional “gray” spaces increase significantly. Special attention is paid to ventilation of interior spaces and to blocking sunlight from penetrating the buildings. Local microclimates in any of these areas allow deviations from normal patterns.

The classic design of a fully developed Chinese courtyard is the Beijing siheyuan, a quadrangle of low buildings enclosing a courtyard, whose origins go back to the eleventh century BCE. Siheyuan are distinguished by being enclosed within gray brick walls with only a single entry—back and side walls lack both windows and doors; orientation to the cardinal directions with main halls generally facing south or southeast; balanced side-to-side symmetry in terms of layout; and a well-defined axis with an implied hierarchical organization of space. Each siheyuan has at least one courtyard at its center, covering about 40 percent of the total area of the dwelling complex, while many have a sequential series of subsidiary courtyards to the front and/or rear. Privacy and security are provided in residential sanctuaries of this sort, with public spaces towards the front and with increasing levels of personal spaces as one moves from outside to inside. In Beijing, siheyuan are the basic components of a checkerboard pattern of low-rise neighborhoods tightly packed along narrow lanes called hutong.

Modularized quadrangular dwellings show striking regional differences that reveal the versatility and flexibility of a basic form even as they all are called by the common name siheyuan. Mountain dwellings in northern China often have what appear to be miniature courtyards embraced by similarly small buildings. In the northeast region beyond the Great Wall, for example, siheyuan courtyards are quite broad; in Shanxi and Shaanxi provinces, on the other hand, siheyuan courtyards are elongated and narrow. Because of very hot summers and severe winters, buildings in central Shanxi are placed closer together than is the case in the Beijing area so that direct and intense sunlight is blocked during the summer from entering rooms except in the early morning and late afternoon, while the surrounding tight structures with high walls reduce the intrusion of cold winds in winter. In Fujian, as can be seen in the eighteenth-century Wu family dwelling in Quanzhou, small courtyards can be linked in a series of adjacent house–yard complexes.

While differing in details, the dwelling types shown here all include the fundamental elements of Chinese architecture: enclosure, axiality, hierarchy, and symmetry. The central image is that of a classic Beijing siheyuan or quadrangular courtyard house.

Side rooms come in many shapes, including this arcuate—cave-like—form in the Fan family residence, Pingyao, Shanxi.

While the typical courtyard of a siheyuan emerges in the void or open space formed by the buildings that enclose it, sunken courtyards are carved into the earth in northern Henan and southern Shanxi provinces. Here, a courtyard for an underground or subterranean dwelling, sometimes called a cave dwelling, is in fact formed first, the initial “constructed” component of the dwelling complex whose “walls” provide the exposed surfaces into which the adjacent residential “structures” are then dug. A sunken courtyard of this type thus becomes a “walled” compound with a core outdoor living space open to the sky, just as with any courtyard built directly on the surface. Elsewhere in China, circular, elliptical, trapezoidal, rectangular, even octagonal courtyards are found within surrounding walls.

Throughout southern China, as mentioned above, dwellings are often punctuated with abbreviated rectangular open spaces or cavities that local people refer to as “courtyards” but which in fact are skywells or tianjing. Although usually quite small and compact, with a restricted openness to the broad sky above, skywells respond well to the hot and humid conditions characteristic of southern China where they catch passing breezes, evacuate interior heat, and lead rainwater into dwellings. The most distinctive tianjing -style dwellings are found in multistoried merchant dwellings in Anhui, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang provinces, centered on an area historically known as Huizhou, which appear like squat boxes or elongated loafs with solid walls and limited windows on the exterior walls. On the inside of these compact structures, there are usually several skywells, each an atrium-like enclosed vertical space whose size, shape, and number vary according to the overall scale of the dwelling. Some of the best examples of these dwellings survive from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) but significantly larger numbers exist from the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). There are structural and aesthetic differences when comparing Ming and Qing dwellings in this area, with Qing residences usually having a greater profusion of expensive woods as well as carved stone and brick that are used structurally and ornamentally in the spaces adjacent to the tianjing.

Close-up of the lattice doors of a side hall under the narrow eaves of a renovated courtyard dwelling in Beijing.

From northeast to southeast in four regions of China, open spaces decrease in proportion to enclosed built spaces so that broad courtyards become increasingly smaller, eventually being mere sky-wells. Transitional gray spaces increase in significance from north to south.

Much of imperial Beijing in the past was laid out like a chessboard with well-defined neighborhoods developed along parallel lanes. Called hutong, these narrow lanes were said to be “like ox hair” in that their number was beyond calculation.

In Langzhong, Sichuan, low buildings—residences-cum-shops—are arranged along narrow parallel lanes.

While some open spaces are designed into a dwelling’s plan and immediately “built” as part of it, others emerge over time as a house becomes more complicated in terms of its layout. An I-shaped rectangular house in northern and in some parts of coastal southern China becomes L-shaped with the addition of a perpendicular wing, then a U-shape with a facing perpendicular wing—in the process embracing a well-defined open courtyard. Enclosing the fourth side leads to a true quadrangular dwelling with a courtyard at its core. In southern China, a rectangular structure is more likely to expand towards the front or the back as enclosed space is doubled with open spaces—skywells—emerging in the interior of the building’s mass as the house grows. Whether in the north or the south, perimeter walls and the surrounding structures effectively block out sounds from the outside, leaving the interior open spaces relatively quiet and quite private.

Framed by a pair of wing buildings, the narrow and elongated courtyard—even here divided into “inner” and “outer” portions—is only as wide as the central bay of the main structure on the left. Xi’an area, Shaanxi.

The inward-sloping roofs of the wing structures lead water into the slender courtyard of the Fan family house, Pingyao, Shanxi. Viewed from a high vantage point, the small spaces, called tianjing or “skywells,” which are integral parts of dwellings in southern and southwestern China, help ventilate the interiors while providing some light and water to the interior. Langzhong, Sichuan.

Over a period of time as a family’s circumstances improve, dwellings tend to grow from a three-bay rectangle, shown here on the left, to more complex shapes. The top drawing shows the common pattern in northern China where, first, an L-shape emerges and then an inverted U-shape, before full enclosure of a courtyard within a rectangle. In southern China, as the bottom drawing reveals, additions are sometimes added to the front or back with small “skywells” situated within the growing mass.

Whether compact or spread out, many Chinese houses exhibit a clear spatial hierarchy that mirrors the relationships among the family living within it and their interaction with visitors. Adjacent open and closed spaces help define this spatial hierarchy, aided in fundamental ways by the purposeful use of gates, screen walls, and steps. Casual visitors, for example, in the past were only invited into the front part of the house, perhaps only the entry vestibule near the main gate or into the first slender courtyard. The larger courtyard and the Main Hall were accessible only to family members. In addition, privileged spaces for women in the family were placed deeper in northern houses and in upper stories of southern houses, far from places where non-family visitors would see them. Separate passageways and doors sometimes helped enforce segregation. In some extensive residential complexes, moreover, a barely noticeable increase in elevation from the exterior to the interior, with each structure a few steps higher than the preceding courtyard, was employed to accentuate status differences from the outside deep into the interior. For women, the bed was a space for more than sleeping, whether it was a simple platform or an elevated brick surface heated from a nearby stove. A woman’s bed often was a rectangular structure with its own architecture, raised on a dais with doors and screen walls that made it a veritable room within a room.

Framed with a cracked ice lattice pattern, this moon gate leads from one courtyard to another. Wang family manor, Jingsheng village, Lingshi county, Shanxi.

Indeed, whenever possible, open spaces—whatever the dimensions and however enclosed by buildings—are nearly obligatory elements of traditional Chinese houses. Open spaces offer abundant advantages in terms of providing enhanced ventilation and sunlight, a place to gather and work, and privacy and safety. Buildings are typically arranged symmetrically, facing each other around courtyards, with the principal building, usually where the main ceremonial hall is located, orientated towards the south or southeast. In many areas of northern China, this principal building is referred to as “northern building” or “upper building,” both indicating a superior position. Side halls then can easily be designated “east hall” and “west hall” using descriptions that are both tied to the cardinal directions and hierarchy.

Many houses, especially those in Beijing, are meant to be viewed from the south, with the observer looking up towards the main structure with its striking façade. Balanced side-to-side symmetry is revealed in the floor plans of virtually all larger fully developed Chinese houses. The mansion of the Kong family, descendants of Confucius, in Qufu, Shandong province, is a fine example of an extensive siheyuan for an official of the first rank. It occupies some 4.6 hectares, including yamen or offices in front where the Duke of Yansheng administered the town, inner quarters for women, an eastern study, a western study, and gardens. Walls, gates, halls, side halls, and courtyards were all laid out in a plan that made hierarchy and status explicit.

Enclosing Spaces: Building Structure and Materials

Whether found in an opulent palace or a humble home, the common denominator of any Chinese structure is a modular building unit known as a jian. A jian is not only a fundamental measure of width, the span between two lateral columns that constitutes a bay, but it also represents the two-dimensional floor space bounded between four columns, as well as the volumetric measure of the void defined by the floor and the walls. Sometimes a jian forms “a room” although often a room is made up of several structural jian. In Chinese dwellings, it is rare for any effort to be made to hide structural columns that give shape to a jian, thus each stands not only as a marker of space but as a natural aesthetic element as well.

Jian: Building Module

Most rural Chinese dwellings are relatively simple I-shaped structures comprising at least three jian. Regional variations in the height, width, and depth of the jian naturally lead to differences in appearance from one area of China to another. In northern China, jian range in width between 3.3 and 3.6 meters while they are typically wider, between 3.6 and 3.9 meters, in southern China. The depth of a bay—often as much as 6.6 meters—in southern China is also usually greater than the 4.8-meter depth common in the north. Throughout the country, jian are usually found in odd-numbered units— three or five—as this is believed by many Chinese to afford balance and symmetry, a configuration seen sometimes in the façades of gravesites constructed to look like a dwelling as well as in even greater odd multiples in imperial palaces. As I-shaped dwellings evolve into L-shaped or U-shaped structures, jian serve as easily multiplied modular units for the expansion of a house.

During the Ming dynasty, especially, sumptuary regulations ordered the dimensions of timber that could be used by princes, ranked individuals, merchants, and commoners, contributing in the process to the standardization and modularization of Chinese houses. The central jian of a three- or five-bay rectangular dwelling, moreover, is generally wider than flanking jian since it often serves as the principal ceremonial or utility “room” of the house, an auspiciously located space that is symbolic of a family’s unity and continuity. Here, a standard set of furniture would be symmetrically arranged: along the back wall, and facing the entryway is the place for a long table to hold the ancestral tablets, images of gods and goddesses, family mementos, and ceremonial paraphernalia. It was here that a family gathered for ancestral rituals, enjoyed festive family meals, including those that were part of weddings and funerals, entertained important guests, and carried out day-to-day activities. Whether open and apparent or enclosed and hidden, the use of jian as a building module is a basic element in the design of most Chinese houses.

Chinese houses and other buildings generally take shape from a conventional set of elementary parts—foundation, wooden framework, and roof— using readily available building materials such as earth, timber, and stone. Many old dwellings throughout the country lack a wooden framework, so that load-bearing walls directly support the roof system, a condition that is almost universal with contemporary Chinese houses. Basements are rare in Chinese dwellings and most houses traditionally were built directly on compacted earth that had been leveled or slightly raised on a solid podium of tamped earth or layered stone. In some cases, a shallow trench was dug, filled with pebble stone and then earth, which was tamped firm with a rammer operated by two men. Stone foundations can be seen supporting the walls of small and large dwellings all over China in order to create a dry and secure base. Some extend a meter or two above the tamped earth podium and are composed of rocks of various shapes and sizes, which are laid with or without mortar. Foundations of this sort are stable enough to support a tamped earth, adobe, or fired brick wall above, which then either supports the roof structure directly or merely serves as a curtain wall around a timber framework.

A jian or bay is a building module representing the distance between two columns, as well as four columns in addition to the volume bounded by four columns— literally representing a room.

The courtyard, as the center of family life, has always been the location for ornamentation, whether permanently applied to the buildings or hung seasonally as the months pass. Fan family residence, Pingyao, Shanxi.

Timber Framework Types

Load-bearing walls, that is, walls that directly support a roof structure, have a long history of use in common houses throughout China, whether the walls are of adobe brick, fired brick, or tamped earth. With higher quality dwellings seen throughout this book, however, walls do not support the weight of the roof above but are merely curtain walls set between complicated structural wooden frameworks that lift the roof rather than using the walls themselves for this purpose. Independent of the walls, which are thus nonload-bearing, the timber framework is a kind of “osseous” structure analogous to the human skeleton. Liang Sicheng, China’s revered architectural historian, claimed that the use of a timber framework “permits complete freedom in walling and fenestration and, by the simple adjustment of the proportion between walls and openings, renders a house practical and comfortable in any climate from that of tropical Indochina to that of subarctic Manchuria. Due to this extreme flexibility and adaptability, this method of construction could be employed wherever Chinese civilization spread and would effectively shelter occupants from the elements, however diverse they might be. Perhaps nothing analogous is found in Western architecture … until the invention of reinforced concrete and the steel framing systems of the twentieth century” (Liang, 1984: 8).

Photographed early in the twentieth century in either Shaanxi or Shanxi province in northern China, these workmen are hefting a heavy rammer in order to tamp the foundation for a building.

The façade of this omega-shaped tomb includes a three-bay structure similar to that of a dwelling. Here, the space is used for periodic ritual purposes.

While common dwellings throughout China are usually three bays in width, those in northern China (left) are not as deep as those in southern China (right). Northern dwellings also rarely have windows on their back walls while in the south they are more common. In northern China, kang or brick beds, connected to stoves in the kitchen, are common features.

On the left is a columns-and-beams wooden framework, most common in northern China. With larger diameter corner columns and heavy beams, this type differs from the pillars-and-transverse tie beams (right), with multiple pillars and thin beams that are either mortised directly into or tenoned through the slender pillars.

Wooden structural frameworks lifting the roof were universally used in the construction of Chinese temples and palaces as well as the houses of those with the means to purchase expensive timber parts for the pillars and beams. The houses built by ordinary Chinese, on the other hand, almost always utilized limited amounts of timber because of cost and other factors, and thus generally were built with load-bearing walls. Timber framework structures can be essentially assembled from standard modular parts rather than being “constructed” using building materials. In no other feature of traditional Chinese housing was the prosperity of the owner so clearly expressed than that of the wooden frame since the cost of timber always far exceeded that of the earth required to compose the walls, even when fired bricks were used.

Two basic wood framework systems—columns-and-beams and pillars-and-transverse-tie beams— are common throughout the country, with some being rather simple while others are elaborate. Columns-and-beams construction is widespread in northern China but is employed only in grander houses in southern China where slender pillars-and-transverse-tie beam frameworks are more common. Both of these framing systems are illustrated in Qing dynasty woodblock prints that contrast a variety of types, including common three-column framing systems with lighter seven-pillar frames. Although the term “column” and “pillar” are usually described in Chinese using the same term, they are differentiated here in English in terms of “columns” being thicker than slender “pillars.” A pair of columns typically is able to directly support a heavy beam without bowing under the weight while the rigidity of a set of parallel pillars and its ability to support a heavy load is only made possible because of the use of transverse tie beams mortised and tenoned into the pillars.

Columns-and-beams construction, referred to in Chinese as the tailiang framing system, may be as simple as a pair of columns situated as corner posts and used to support a single beam, which is either laid atop and perpendicular to the columns or slightly inclined to create a flat- or shed-like roof. Even in small northern dwellings, tailiang structures are often more complicated, involving a stacking of building parts in order for there to be a rise to a central peak so as to produce a double sloping roof. First, two squat queen posts, or struts, are set symmetrically upon the horizontal beam. On top of the pair of queen posts another beam is set. Then a culminating short post is placed. A matching pair of columns and beams is situated at the opposite end of the house. A longitudinal ridgepole, which defines the peak of a triangular roof, as well as parallel purlins, which are the longitudinal timbers that are seated directly on the beams, connect the pair of end column-and-beam sets which are piled perpendicular to the ridgepole and purlins. Together, they provide support for roof rafters bearing the weight of roof tiles and carrying the massive load to the ground.

All embedded into the wall, corner columns and short stocky queen posts lift three tiers of massive beams that support a heavy roof. Beijing.

Variations in framing sometimes occur in order to accommodate available timber, some of which may not be straight or the same length as corresponding members. The upper cross section of a tailiang structure is made up of only vertical and horizontal elements, which may be positioned in such a way as to introduce a degree of curvature into the roofline by creating at least one break in the slope of the roof. This is quite different from what is possible with the rigid roof truss system based upon triangularly positioned segments that is common in the West. Chinese builders and homeowners traditionally held the belief that placing great weight on the roof insured a building’s sturdiness. Indeed, in northern China, wooden timbers are often massive in size, far beyond what is actually necessary to support the roof.

The pillars-and-transverse-tie beams wooden framework, also called the chuandou framing system, is common throughout southern China. It differs from the tailiang system in three important ways: the number of vertical components is greater, yet the pillars all have a smaller diameter; each of the slender pillars is notched at the top to directly support a longitudinal roof purlin; and horizontal tie beam members, called chuanfang, are mortised directly into or tenoned through the pillars in order to inhibit skewing of what would otherwise be a relatively flexible frame. Smaller diameter chuandou pillars, often only 20 to 30 centimeters, are less expensive than the larger timbers required in a tailiang frame. Trees as young as five years can be used for purlins, chuandou pillars, and tie beams, while it takes at least a generation for columns and beams to mature to sufficient size for use in a tailiang structure. Sometimes in southern China, the lower wall of a two-story dwelling may be solid masonry or it may utilize a columns-and-beams structure while the upper story supporting the roof uses a lighter chuandou wooden framework.

The positions of purlins in terms of the spacing of the pillars supporting them and the elevation of each define the slope of the roof, which varies significantly from place to place. Where the relative position of the purlins remains fixed, there is a constant downward slope to the roofline, without a break. If a curved roofline is desired, the pitch is then varied from one purlin to another in a regular mathematical relationship. Carpenters’ manuals provided guidance for builders of palaces and temples, whose wooden frameworks are quite complex, but carpenters engaged in building houses typically drew from their experience rather than the written word. In rural China today, it is still possible to encounter carpenters who depend upon mnemonic verses committed to memory in order to recall the necessary formulas for required sizes and shapes. In the past, mnemonic verses also were the means used to transmit this specialized knowledge to apprentices, but young carpenters now can find the same information in readily available manuals.

This pillars-and-transversetie beams wooden framework, comprised of timbers of relatively modest diameter, was raised first and was covered with a roof even before the infilling of the curtain walls was begun. Emeishan area, western Sichuan.

Viewed from inside the kitchen, both the pillars and the transverse tie beams are visible. The space between pillars and beams was filled with nonload-bearing panels of woven bamboo that were then covered with mud plaster before being whitewashed. Nanchong, Sichuan.

Horizontal and vertical carved wooden members, including supporting brackets, serve more decorative than functional purposes at an entry to the Ning’an Lu residence, Nankou township, Meixian, Guangdong.

Close-up of wooden ornamentation attached to the pillars and beams using mortise-and-tenon joinery. Fan family residence, Ping-yao, Shanxi.

These drawings show complex mortise-and-tenon wooden joinery found at the Hemudu Neolithic archaeological site in Zhejiang province, clear evidence of such practices in China 7000 years ago.

The wooden framework of a new house in western Sichuan, as seen on the previous page, employs an interconnected pillars-and-transversetie beam skeleton. Its various components provide connections needed to link one modular unit with another. Of seven interlocked pillars that directly support the purlins, only five reach to the ground. A transverse tie beam halfway up the frame serves as a base for two additional pillars while also locking the pillars together. Mortised, tenoned, and notched joinery is apparent.

Carpenters wielding a simple adze dress each timber on a trestle sawhorse, marking locations for every mortise and tenon before each is chiseled to shape. Elements of the framework are assembled into a unit on the ground before being raised to a perpendicular location, where they are then propped and secured to adjacent segments by longitudinal cross members. The raising of the ridgepole as well as some of the columns is an especially important action in Chinese house-building, a subject discussed later. Wooden or bamboo roof rafters are laid cross-wise between the purlins to serve as the base for layers of roof tiles. Lifted by the wooden framework, the mass of the heavy roof helps anchor the structure even before the wall infilling is put into place.

Mortise-and-Tenon Joinery

Tailiang wooden frames depend principally on the dead weight of beams as well as dowels and wedges to insure a snug fit. On the other hand, until the twentieth century, chuandou frames relied only on ingenuous joinery systems, sometimes assisted by wooden pegs, to interlock the wooden structural components. The basic elements of chuandou mortise-and-tenon joinery include tenons, which are shaped to fit into cut-out mortised openings in order to create a strong joint capable of expanding according to changing temperature and humidity conditions. (Joinery of this type is used for both Chinese buildings and Chinese furniture, and draws on practices that can be traced back 7000 years via archaeological evidence at the Hemudu site in Zhejiang province during the Neolithic period.) “Mortises,” Rudolf Hommel observed more than sixty years ago, “are an infatuation of the Chinese carpenter” (1937: 299). Metal fittings such as nails and clamps until recently have had only limited use in Chinese timber frame construction because of suitable alternatives, cost, and the fact that they sometimes disintegrate and lead to structural failure. The clever use of mortise-and-tenon as well as other joinery techniques makes it possible to assemble even pieces of timber of different sizes together into an interlocked frame. Chuandou wooden frameworks are especially adaptable for construction on hill slopes and river banks where the lengths of timbers vary according to the specific needs of the sites.

In most cases, the various components making up a timber frame—whether tailiang or chuandou — are left fully exposed although sometimes they are embedded within the wall. Their natural outline can be enjoyed as an aesthetic element as can often be seen in the interplay of columns and beams and the displays of intricate carpentry used in fashioning brackets that support overhanging eaves.

Both columns and pillars are usually set on stone or brick bases in order to retard the transmission of moisture and make difficult the movement of termites from the ground below into the vulnerable wooden uprights above. Bases, also called pedestals, are often roughly hewn stone blocks, either chamfered along the top or edges or gently rounded, but in large dwellings are usually carved into elaborate shapes—drums, octagons, and lotuses, among many others—and ornamented with auspicious symbols. Bases themselves frequently are set on a stabilizing slab of stone sunk into the ground or floor.

Nonload-Bearing Curtain Walls

In order to protect interior space given shape by the timber framing system, many types of exterior walling are employed: tamped earth, adobe brick, fired brick, stone, wooden logs or planks, bamboo, wattle, and daub. Walls that enclose and surround space also protect and divide it, and it is common to see a variety of wall materials used in a single house. In southern China, nonload-bearing walling is sometimes of vegetative origin, utilizing grasses, grain stalks, and even cob walls mixed with sand and straw that are not even capable of supporting any mass other than their own. Sawn timber and bamboo are also used.

One of a pair of carved stone drums with characters for “longevity” and “good fortune” found at the entrance of a doorway. Wang family manor, Shanxi.

Ornamented stone column bases or pedestals are common features of Chinese houses, appearing in a large variety. Top left: Fan family residence, Pingyao, Shanxi. Top right: De Xing Tang, Meixian, Guangdong, which includes a stone column; Bottom right: Ning’an Lu residence, Meixian, Guangdong; Bottom left: Deng family residence, Guang’an, Sichuan.

Sturdy load-bearing walls—far more common in the construction of Chinese dwellings than is generally acknowledged—are made of a variety of natural materials that are tamped, formed, or hewn. These same substantial materials are used to form nonload-bearing curtain walls, either completely encircling the wooden skeleton or simply filling the gaps between the columns or pillars. Tamped walls, described in greater detail below, are composed of mixtures of clay-textured soils as well as composite amalgamations of other substances. Blocks of clay are molded into bricks that can be either sun-dried or kiln-fired. Chinese builders generally show a decided preference for earthen structures, so that stone and rock are not used in housing construction to the degree that matches their availability. Hewn stone, particularly granite, is a common material in coastal areas of southern China, where it is employed in laying up the lower courses of walls, for floors, and as columns. Collected from riverbeds and gathered from hill slopes, stones of various sizes are laid up as low walls in many parts of the country. Both load-bearing and nonload-bearing walls are sometimes made of a mixture of locally available building materials, arising out of availability and/or cost factors.

Tamped Earth

Tamping or pounding clay soil or other materials— called the hangtu method of construction—has been used for much of Chinese history to create solid walls for houses and other buildings, including imperial palaces. In addition, this method was widely used to fortify villages and cities with high protective walls and enclose compounds and open areas as well, an economical and low-tech practice that can still be seen throughout much of rural China. The emperor of Qin in the third century BCE supervised the construction of an immense range of tamped earthen walls to demarcate borders, precursor forms of what today is China’s legendary Great Wall. The firing of bricks also was common by the third century BCE but did not become economical and widely available for housing construction until the fourteenth century, so tamped earth and adobe bricks continued to be preferred walling until at least the Ming dynasty; even today, tamped earthen walls continue to be raised all over China for utilitarian and economic reasons.

Throughout China, the use of hangtu construction arises out of the ubiquity of accessible clay soils, generally found immediately adjacent to building sites and thus requiring no transport of heavy materials over any distance, as well as the scarcity and cost of alternative building materials. In spite of being a remarkably durable building material, tamped earth, however, has some fundamental limitations, especially weaknesses in supporting heavy loads and relative inflexibility in the placement of windows and doors. Yet, even large structures, such as the multistoried fortifications in Fujian and Guangdong, have been built using this simple technique.

Known in the West as rammed or tamped earth, the hangtu method involves piling freshly dug earth into a slightly battered frame where it is pounded firmly with a rammer. Local formulas often include sand as well as lime with the earth in order to create a material that is mortar-like in composition. A common mixture in central China is 60 percent fine sand, 30 percent lime (ground limestone or shells), and 10 percent earth mixed with a small amount of water.

In northern China, the basic frame consists of a confining shutter mold with a pair of H-shaped supports reaching perhaps four meters in height that are framed on their long sides by movable wooden poles lashed together with thin rope or held by dowels.

This seventeenth-century woodblock print depicts the traditional framing system employed in raising a tamped earth wall.

The thin poles can be quickly and easily raised up the sloping supports, level by level, as the ramming takes place. Each of the poles must be periodically removed and cleaned of clinging earth. Shuttering boards are used instead of timber poles in southern China as a three-sided box frame formwork, without either a cover or bottom, and these vary in size from place to place. An end board with projecting tenons secured by wooden pegs holds the flanking boards together on one end while the other is held by an easily manipulated crosspiece that grips the bottom flanks of the frame and which passes through the rising wall. An end clamp or a set of braces tightens the frame. A plumb line weighted with a stone serves as a simple level. Freshly dug earth or a composite material—perhaps 10 centimeters thick at a time— is mixed with a small amount of broken grain stalks, paper, lime, and sometimes water or oil, and then pounded with a stone or wooden rammer until it is uniformly compacted. A typical rammer is made of a heavy stone head, perhaps 25 centimeters wide, which is rounded on the bottom and attached to a projecting wooden rod. In some areas, rammers consist of a single piece of hardwood with a large wooden block carved into one end and a smaller one chiseled on the other end, a configuration that is reminiscent of the pestles used to husk rice. Smaller tools of various sizes are used to insure that the soil mixture is firmly packed. In some areas, a thin layer of bamboo strips or stone rubble may be laid to encourage drying of the earthen core before the movable shutters of the frame are raised, leveled, and clamped into place, to begin the process anew. The sequence is repeated until the desired height is met.

Spaces for the frames of windows and doors can be set into the rising tamped earth wall using wooden or stone lintels, but it is necessary to carve out the opening in the compacted soil within the frames once the wall is completed. Because of the weakening of the wall with such openings, care is taken to limit their number and size so as not to diminish the wall’s ability to carry the weight of the rising mass and eventually the roof as well. With multistoried dwellings in Fujian province, windows in the walls are narrower near the base and increase in width on upper floors. The full drying of the exterior surface may take months, depending on rainfall and humidity levels. Once the wall cures completely, a soil-and-lime based slurry plaster may be spread over the wall.

As this old photograph shows, a box frame with a small block on one end and a larger block on the other— held together with cross bars and secured with dowels— can be filled with earth or an earthen mixture before being tamped firm with wooden rammers. Guling, northern Jiangxi. Similar practices are still observable in south central China.

Captured in 1984 in Shaanxi province, this photograph reveals the continuing use of the centuries-old method of tamping walls using stone rammers and a frame made of shuttered logs.

Tiangong kaiwu (The Creations of Nature and Man), a seventeenth-century work on technological topics, depicts the use of a shallow wooden frame into which soft mud was placed to form a brick. A wire-strung bow was used to cut off excess mud once the mud had been tamped firmly. Formed bricks are shown being carried by an assistant to a nearby area for drying.

The use of kilns to fire thin bricks and roof tiles, shown here stacked in the rear, became popular during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). In this depiction from the Tiangong kaiwu, water is poured into the top of the kiln in order to create a superficial glazing on the surfaces of the bricks being fired within.

Sun-dried Bricks

Sun-dried bricks or adobe bricks retain many of the economic characteristics of tamped earth but allow greater flexibility in building form. The earliest use of adobe bricks in China appears to have simply supplemented hangtu construction in that bricks were used to build stairs, frame gateways, form interior partition walls, and make the heatable beds, known as kang, that are found throughout northern China. Even today, new houses in many villages throughout rural China are being built at relatively low cost of adobe bricks as well as tamped earth even as news reports tell of the vulnerability of earthen buildings in China because of natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes. If compacted well and dried completely, adobe bricks become stone-like, but, if improperly cured, become friable.

Bricks, whether sun- or kiln-dried, are made using relatively common techniques applied to locally available soils near a building site, just as is the case with hangtu walls. The seventeenth-century manual Tiangong kaiwu (The Creations of Nature and Man) depicts techniques of brick manufacture still encountered throughout China today. First, moistened clay soil dug from nearby is formed by hand in double non-releasable molds, trimmed with a bow-shaped wire cutter, before two uniform bricks are dumped from the frame and left to cure. In other cases, earth is packed into a mold, shaped by hand, and then pounded with the feet or a stone pestle to firmly compact the soil. Bricks made from moistened soil are usually thicker and broader but shorter than those made from completely dry earth. However they are made, the bricks are stacked for drying and usually capped with a sloping cover of straw to keep them from getting wet from passing showers.

Adobe bricks, as thick rectangular slices, are sometimes simply cut from the bottom of rice fields, not only to produce a necessary building material but also to correct for the natural siltation of fields. In parts of southern China, this is usually done every ten years or so during the fall after the field has been plowed, harrowed, and compressed with a stone roller. Once the fields have been puddled from a heavy rain and evaporation has reduced the moisture content of the soil to a dense yet viscous consistency, brick-size sections of earth, each approximately 15 centimeters thick, are sliced and lifted from the floor of the field with a spade. In some areas, rough-cut bricks are simply stacked to dry, but in Guangxi each segment of paddy floor is placed in a simple wooden and bamboo frame where the soil is then tamped with the feet to a common shape. Once the brick is molded, the bamboo handle of the shaping frame is lifted and the brick is allowed to dry for days in situ adjacent to other bricks. Later stacked and left to cure for several weeks under a straw cap, the adobe bricks are ready for use.

Kiln-dried Bricks

Although it was not until the Ming dynasty in the fourteenth century that fired bricks became relatively inexpensive and widely used, the practice of using fired bricks in residences gained currency by the Han dynasty in the third century BCE. Kiln-dried bricks are a qualitative improvement over inferior adobe bricks in terms of durability, imperviousness to water, and fire resistance, but they have always been significantly more costly because of the extraordinary amounts of fuel necessary to bake them. The firing of bricks at temperatures that reach 1150° C essentially changes the raw soil that constitutes them as sintering and partial vitrification take place, to the degree that baked bricks cannot be pulverized, reconstituted, and then reused as is the case with adobe bricks. Throughout China, fired bricks vary significantly in color as a consequence of the different types of soils utilized in making them as well as the techniques employed in firing and cooling them.

In some areas of southern China, bricks are cut from paddy fields, producing not only a needed building material but also providing a means to correct the natural siltation of the fields by removing the excess earth. Lipu county, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.

Near the end of the twentieth century in China’s countryside, bricks continued to be made using similar techniques to those shown in the seventeenth-century drawing on the previous page. Just as in the print, the worker stands in a depression to ease the tamping of the mud and his use of the wire bow. Zhejiang.

Only about 20 percent of all rural dwellings surveyed in China in the early 1930s had kiln-dried brick walls, with most of them being found in prosperous areas, such as in the fertile rice-growing valleys and lowlands of central and southern China. Over the past quarter century, as China’s house-building boom has led to increasing numbers of boxy adobe and fired brick houses, it has been possible to observe traditional production and construction practices throughout the country. From preparation of the soil to forming to firing, the making of baked bricks is a specialized process that demands higher levels of skill and technological know-how than is the case in making adobe bricks, in addition to consuming substantial amounts of fuel. Many Chinese also prefer the texture and color of fired brick to walls made of gray cement.

The use of adobe bricks or fired bricks is a tangible statement of a household’s general wealth. Poorer households primarily use tamped earth and adobe bricks while those who can afford them prefer kiln-dried bricks. Chinese peasants in the past were known to replace portions of a tamped earth wall with adobe bricks and then later substitute fired bricks for adobe piece by piece in their search for strength, durability, and resistance to water. This level of resourcefulness can still be observed today as farmers attempt to stretch their financial resources. Some modern dwellings employ fired bricks in visible locations while utilizing cement or stone in less obvious places. Brick bonds, the patterned arrangement of individual bricks across a wall surface, vary from place to place in China. Most bonds are similar to those seen in the West.

Adobe bricks vary in size from place to place. The walls of the Mao family farmhouse in northern Hunan province— viewed from both the inside and the outside—show the use of large 34 by 11.5 cm adobe bricks. Bricks of this sort were made in molds and then left to dry before being used. Over time, the bricks continued to harden as they were exposed to the sun and warm air.

Fired bricks are employed in the interior party walls of this building even though the exterior walls are constructed of tamped earth. Fu Yu Lou residence, Hongkeng village, Fujian.

Producing a composite wall surface, the red brick exterior walls along this narrow lane have within them readily available blocks of granite. Quanzhou, Fujian.

Bamboo

This is among the most versatile of all plant materials used in building Chinese houses. Its use is especially common from Sichuan through Hunan and Hebei in the middle reaches of the Yangzi River as well as in Yunnan and Guizhou provinces where it is used widely in house-building by members of ethnic minority groups. Bamboo, a multipurpose grass that grows rapidly and in many forms, has many structural qualities—strong yet light, rigid yet pliant— but also has certain shortcomings—difficult to join as well as vulnerable to splitting, rotting, and burning. Because the cylindrical shells of bamboo come in different sizes and can be easily cut, split, and worked with simple tools, it is an all-purpose building material. Bamboo is used for framing members and floor joists, for roof components such as rafters, purlins, and ridgepoles, as well as a variety of walling forms. When split and with their inner diaphragms scooped out, half rounds of bamboo can be laid as a roof covering, either side by side with the open face up or overlapping as roof “tiles.”

For walling, bamboo culms are split into thin flexible splines that are interlaced at a 90-degree angle to form a kind of woven lattice or lathing matting that can be used for all or part of the wall. Bamboo plaited curtain walls are often sealed with a mud or mud-and-lime plaster on both sides to make the wall tight to air and water. Those seen in Sichuan and Jiangxi provinces remind some Westerners of simple vernacular half-timbered dwellings seen in England and Germany. According to surveys done in the 1930s, nearly 30 percent of houses countrywide had walls of woven plant materials while in southwestern China the percentage reached nearly two-thirds. Even in moderately prosperous Taiwan, as recently as 1958, dwellings that included substantial amounts of bamboo, rather than adobe or fired brick, represented 40 percent of rural dwellings.

Despite its ubiquity, versatility, and long history of use, bamboo nonetheless has significant shortcomings. Compared to wood, for example, bamboo rots easily, especially when in contact with damp soil. It is vulnerable to insects such as termites and is also highly inflammable. As a result, bamboo paneling is usually found in higher locations on a wall rather than nearer the ground. Today, it is rare to find much bamboo used structurally in Chinese houses. Even ethnic minority groups, such as the Dai in Yunnan province who were known in the past for their zhulou or “stilt bamboo storied-houses,” which are elaborate structures with multiple roof pitches, today usually construct their houses of wooden poles with wooden walling. Peculiarly, they continue to refer to the structures as zhulou. Even as bamboo has declined as a building component, it remains an important quick-growing, versatile raw material as the extensive hillside stands and ubiquitous thickets of bamboo suggest. Some architects interested in promoting sustainable building practices have called for increasing the use of structural bamboo by substituting fast-growing bamboo for timber, which increasingly is costly and sometimes in short supply. Used in making furniture, mats, artwork, fences, baskets, ornaments, cables, stakes, umbrellas, baby carriages, cooking vessels, boxes, needles, shoulder poles, and baskets, among many items, bamboo continues to rival more modern materials in Chinese daily life.

Itinerant workers are splitting bamboo into thin splines that are then interlaced to form wall panels. Zhejiang.

The interlaced bamboo wall panels are sealed first with a mud or mud-and-lime plaster before being whitewashed. Langzhong, Sichuan.

Sorghum and Corn Stalks

Although commonly used by poor peasants in northern and northeastern China up until the middle of the twentieth century, sorghum, also called kaoliang, and corn stalks are rarely seen today used in the walls of houses. In the past, grain stalks were packed together, stood on end against an unfinished wall frame before being crudely plastered with mud as a kind of daub. Sometimes a second layer of stalks was placed inside the house that, after being plastered, would leave a dead air space between itself and the outside wall to serve as insulation.

Stone

This is not used in China as a building material to the degree that matches its availability except in relatively barren mountainous and coastal areas where soil suitable for tamping or making bricks is limited. On the other hand, stone is widely used for foundations, in lower walls, for making steps and pavements, and is sometimes hewn for columns and windows.

Close-up of simple wooden lattice window frames showing the tattered paper on the inside. Chuandixia village, Beijing.

Wooden timbers are used here as columns, beams, and eaves brackets—all embedded within the wall—that lift the roof purlins supporting the rafters. Quanzhou, Fujian.

This intricate “cracked ice” lattice pattern is found on a door panel of a renovated siheyuan in Beijing.

Lattice window panels provide variable amounts of light, air, and privacy to interior spaces. Kang family manor, Henan.

In wealthier homes, hard-woods and softwoods are used functionally and ornamentally. Fu Yu Lou Lin family residence, Hongkeng village, Fujian.

Timber

Where forests are extensive in some areas of northwest, southwest, and northeast China, load-bearing walls of roughly hewn logs are built and finished with a mud-plaster. Log cabin-type dwellings have been built and used principally by ethnic minorities in upland areas on China’s periphery. Often log dwellings are built of only simply dressed tree trunks that are placed horizontally one on top of the other so that they overlap to form the corners of the structure. The unhewn logs normally project from the corners but are notched above and below in order to “lock” each of the levels in place in a relatively tight joint.

Sawn wood has never been widely used to form exterior walls in humble dwellings yet it continues to be utilized in houses throughout many of the mountainous areas of central and southern China where timber is readily available. Within the houses of the wealthy, sawn wood was fashioned by carpenters into exquisite wooden latticework as part of door and window panels that complemented carved beams and brackets, serving in the process as flexible fittings for connecting interior and exterior spaces. With most any type of light curtain walls, no attempt is made to conceal the wooden framework so that the natural lines of the wooden pillars and beams beautify the house.

Roof Shapes and Profiles

Although a roof is principally a functional canopy sheltering a structure and its interior living space from the elements, it may also be an expressive feature with sometimes powerful symbolism attached to it. The materials used to cover a roof, its degree of slope, as well as its profile are strongly influenced by both climatic and economic factors. In areas of substantial rainfall, the major concern is quickly moving falling water to the eaves in order to minimize the infiltration of moisture into the building. Pitched roofs—with surfaces that operate to disperse water like the scales of fish or the feathers of birds— are most common on Chinese dwellings. Roofs also contribute to insulating the inside of the dwelling, shielding the inhabitants from either heat or cold. Probably most Chinese roofs are merely utilitarian, providing crude water shedding and waterproofing. The profiles of many, however, exhibit a powerful elegance in terms of their curvature and covering, conditions that are more common in the residences of those with greater means than those who live in humble dwellings. Some scholars have claimed that Chinese pay as much attention to the appearance of the roof as Westerners do to the façade.

In addition to uncomplicated flat and shed types, there are four major Chinese roof styles. For the most part, Chinese roof profiles are symmetrical in side and front elevation, the first emphasizing the gable end of a dwelling and the second the ridge-line. Throughout rural and urban north China, the yingshanding (“firm mountain”) type roof profile exhibits a flush gable with no overhang, a type that is suited to areas of limited rainfall where there is no critical need for shielding the gable end of a dwelling from weathering. Flush gables are also found on houses in southern China where rainfall is plentiful in the coastal areas but the lack of eaves overhang is seen as an advantage to counter strong winds that accompany frequent typhoons. Simple decorative brickwork is sometimes added at the top of the gable or along the ridgeline. There is no record of yingshanding roof profiles prior to the Ming period, the use of which appears to have increased with the expanded availability of fired bricks. Many shanqiang gable walls indeed are load-bearing, directly carrying the purlins and the substantial weight of a tile roof.

The flush gable of this fired brick dwelling is richly ornamented with cloud patterns surrounding a stylized “longevity” character. Kang family manor, Henan.

Matouqiang (“horses’ head wall”), although not properly a “hard mountain type,” is discussed here because it also does not have a gable overhang even as the gable wall rises above the adjacent slope of the roof. A type common in Anhui, Jiangxi, Zhejiang, and southern Jiangsu provinces, where the gable walls rise in dramatic steps above the roofline, matouqiang probably began as firewalls. Forming party or common walls between two structures, matouqiang rise high above the general roof-line in order to retard the spread of sweeping roof fires in adjacent dwellings, temples, clan halls, and other buildings in towns and compact villages. Their use increased during the Ming dynasty as fired bricks became relatively inexpensive. Usually symmetrical in their upper profile, they nonetheless vary significantly. Serving very much like matouqiang are qiaoji (“upward-turning spine”), the sweeping undulation of end walls found in southeastern China. Aesthetically pleasing, stepped matouqiang and soaring qiaoji end walls, which are usually accentuated with dark tile copings that contrast with the white walls below, are distinctive features of Chinese domestic architecture.

A variety of rooflines are seen along the canals in Wuzhen in northern Zhejiang province. On the right, the rather simple matouqiang style also serves as important firewalls.

These stepped gables rising above the slope of the roof of the Main Hall are also called matouqiang, said by some to represent raised “horses’ heads.” Shen family residence, Luzhi, Jiangsu.

The layered rooflines of Fu Yu Lou in Hongkeng village, Fujian, are said to suggest a phoenix taking flight.

A roof type in which the purlins extend out beyond the end walls, thus creating a substantial eaves overhang that offers some protection of the gable walls, is called “overhanging gables” (xuanshanding or tiaoshanding). Found throughout the country, it is peculiar nonetheless that they are not common in some areas of substantial rainfall such as Taiwan and Fujian. Archaeological evidence shows that “overhanging gables” were used during the Eastern Han period but they did not enter the architectural mainstream until more than a half century later, in the Tang period.

Hipped types, called sizhuding or sihuding, utilize four sloping surfaces on the roof, the hip representing the exterior angle where any two slopes come together. They are most commonly seen today on Ming and Qing period palaces, temples, and large residences, presenting a profile that is quite graceful. Involving intricate carpentry of radiating woodwork, they are found nonetheless on some common houses as well and, perhaps surprisingly, even covering quite modest thatched dwellings such as those of the Korean minority nationality. With hipped roofs, sloping eaves similarly overhang the side walls just as they normally overhang the front and back. A complex variant type that is a challenge even to a skilled carpenter is the combined hipped and gable type (xieshanding). Its construction involves the foreshortening of two hipped slopes on the ends of the roof in order to form a gablet, a small triangular gable that fits beneath the peak. This structural type is known in the West as a gambrel roof. The hipped style was widely employed for dwellings prior to the Song dynasty, as can be seen in paintings of many periods. During the subsequent Ming and Qing periods, however, its use became restricted because of the imposition of sumptuary regulations that limited hipped roofs to palace construction. In areas remote from imperial control and occupied by minority groups such as the Dai, Jingpo, De’ang, Blang, and Jino in Yunnan province, many simple dwellings made of bamboo and thatch have rather complex roof profiles, such as the xieshanding, a combined hipped and gable roof.

Embellishments along the ridges and at the eaves enhance the silhouettes of many Chinese houses. Seams along any of the junctures between different roof slopes demand particular attention because it is in these places that seepage of water from outside and loss of heat from inside are most likely to occur. V-shaped and inverted U-shaped capping tiles have a long history of use to seal vulnerable seams, serving critical functional purposes. In addition, these locations also often have rooftop, eave, or gable end ornamentation that suggests other than mere functional explanations.

Concerning the upturned ends of a roof’s ridge, Chinese architectural historians speculate that it resulted from a need to increase protection of an area that might be lifted by the wind, thus exposing the interior to wind and water damage. Over time, areas near the ends of ridgelines acquired heavy, finial-like ornamentation known as chiwei (owl’s tail”) or zhengwen (“animal’s mouth”) that came to serve also as totems guarding against fire. At each end of the ridgeline on many houses in northern China, a brick molding runs along the length of the ridge. Sometimes with a slightly raised extension, even a projection, the raised molding is freely carved with line patterns and even occasionally has ornamentation added atop it. In southern Shaanxi, prefabricated, fired roof ornaments are generically called “ridge mouths” (jiwen) after the traditional “animal mouths,” and are said to have a magical power against the possibility of fire.

Believed by some to be a totem as protection against fire, creatures of this type are found on palaces as well as upon dwellings. Kang family manor, Henan.

Along the ridgeline, a simple ornamental treatment results from using stacked flat roof tiles, here embellished with a coin-like design also made of thin roof tiles. Nanchong, Sichuan.

Adjacent layers of concave and convex tiles across the slope of a roof usually terminate in ornamental end tiles. Yongding, Fujian.

Close-up of two types of ornamental wadang or end tiles, here shown with the patina of mold. The triangular dripping tiles are said to facilitate the movement of water off the roof. Nanchong, Sichuan.

Close-up of molded ornamentation along a tin gutter that utilizes the Chinese character for “purity.” Located in an area visible only to women in their neifang or inner quarters, the character served as a didactic admonition. Hongcun, Anhui.

The making of roof tiles is shown clearly in these drawings from the seventeenth-century manual Tiangong kaiwu (The Creations of Nature and Man). The worker in the center is using a wire bow to slice a thin slab of clay from an oblong block of compacted earth. This slab is wrapped around the side of a flexible cylindrical mold where it is smoothed and shaped by another craftsman. On the right, the cylindrical shape is broken into concave tiles, which are shown stacked in the rear.

Even simple concave roof tiles are arranged in interesting ornamental patterns, including some with auspicious meanings. In Fujian and Taiwan, for example, there are three basic ridge style profiles: the so-called “swallowtail” style, the “horseback” or “saddle” style, and the “tile weighing” style. Graceful “swallowtail” rooflines traditionally were given shape with bricks cantilevered out from the ridge and supported by a metal rod, but today they are more likely to be molded from reinforced concrete. “Horseback” or “saddle” style ridges, while maintaining a low-slung curved ridgeline like the “swallowtail” style, lack the “swallowtail’s” upward sweep at the end of the roof ridge. Gable end profiles known as the “tile weighing” style are found on Hakka dwellings in southern Taiwan, as well as in scattered parts of northern Taiwan. But the meaning of the term goes beyond functionality to describe a guarding or protective purpose for the house.

Roofing Materials

Early roofs on Chinese houses were nothing more than saplings and branches laid on a slope, perhaps supplemented with a mud coating to shed rain and break the wind, while baked roof tiles began to be used as early as the eleventh century BCE. Plants and mud continue to be used as roof covering in some parts of the country, yet tile roofs of many types are ubiquitous throughout China today.

Mud Compositions