Some of China’s most unique structures, the so-called tulou, rammed earthen structures that resemble fortresses, are common in southwestern Fujian with variant forms seen in adjacent areas of Jiangxi and Guangdong provinces. Found in once remote mountainous areas characterized by narrow, sinuous valleys, tulou were virtually unknown and unrecorded until the last half of the twentieth century. Today, many of the villages in which they dominate are increasingly accessible and visited by growing numbers of intrepid travelers wishing to get off the beaten track. It is certain that there are even more secluded villages of tulou yet to be discovered and heralded in the deeper hills. In many villages, it is possible to see tulou in various shapes, including square, pentagonal, octagonal, rhomboid, oblong, and round, with a few built more than 500 years ago and some even just decades ago. Finding an effective translation for the Chinese word lou, which is part of the name of each of these buildings, is difficult. “Storied Building,” the normal translation, does not do the structures justice. The term “Tower” is used here. While towers usually are taller than their diameter, architecturally the term can be used when a structure is of great size even if the height–width proportions differ from general usage.

While the term tulou means “earthen dwelling” and many authors write as if such structures have always been constructed of fresh earth, as indeed is the common building practice in many areas of China, most large-scale tulou seen today were built of a composite material known as sanhetu, a mixture of fine sand, lime, and soil in different ratios, rather than simply earth. Some tulou actually were constructed completely of cut granite or had substantial walls of fired brick. Thus, to call them “earthen dwellings” in English or even tulou in Chinese is clearly erroneous and insufficient. Massive round structures known as yuanlou, common in southwestern Fujian, are the best-known Hakka fortresses but there are many different shapes, including some with concentric circles within them. No less significant are the imposing and impregnable weizi of southern Jiangxi and the often magnificent wufenglou (“five phoenix mansions”) of eastern Guangdong and southwestern Fujian. Unlike castles in Europe and Japan, Hakka fortresses in China are rarely located at high and commanding positions.

Historical and geographical reasons relating to the time of migration and relationship with neighbors help explain the distribution of different shapes of tulou. In the oldest settled Hakka areas, five phoenix and horseshoe shapes were common, probably because early settlers were not seriously threatened. Here, early Hakka arrivals built rather open dwellings in a style that evoked the manor dwellings of officials, the so-called daifu zhai, in areas of northern China from which the Hakka migrated. Imposing round or square bastions were generally built along the borders of Hakka-dominated areas and where Hakka lived among others, yet not all of them were built in response to the potential of strife. Turmoil certainly was often a factor, such as during the early third of last century when many substantial walled enclaves were built all over rural China in response to widespread banditry and general lawlessness, but there were other considerations as well.

Fully a third of all tulou still standing in Nanjing county in the 1990s were built before 1900, but it is a startling fact that some 427, nearly two-thirds, were built after 1900. Over the past ninety years, almost as many large round ones (192) have been built as square ones (235). This relatively recent building history suggests that reasons other than defense played roles in their construction, even given the periodic turmoil of modern times. The accelerated building of structures using traditional materials and forms after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, especially, was a response to population pressures and economic conditions rather than turmoil. In the 1960s, more round structures were built than square ones, but in recent decades square and rectangular shapes have dominated while the number of related households living together has decreased as more families establish single family houses in Fujian’s villages.

Zhen Cheng Lou

Hongkeng village in Yongding county, known as being at the core of a region awash with these distinctive architectural forms, was relatively inaccessible even as recently as 1990, when it was only reachable at the end of a long and rugged dirt path on foot, by bicycle, or in a three-wheeled gas-powered cart. Today, a good road with regular bus service brings backpackers and buses with international tourists.

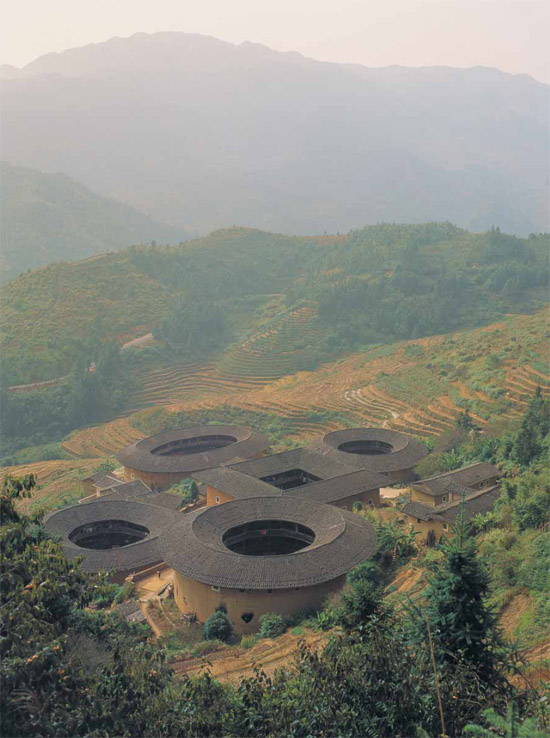

Arranged like landed UFOs, these five enormous rammed earthen ramparts are clustered together along a steep hill slope in Tianluokeng village, Shuyang township, Nanjing county, Fujian.

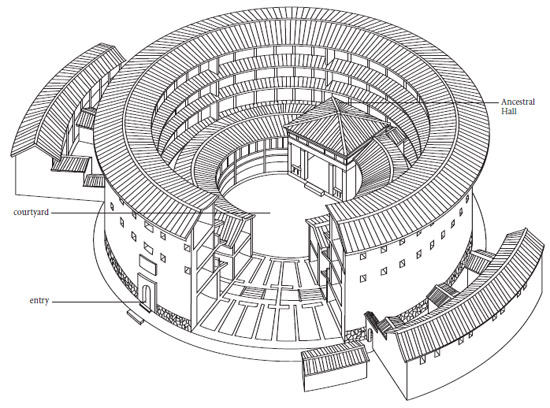

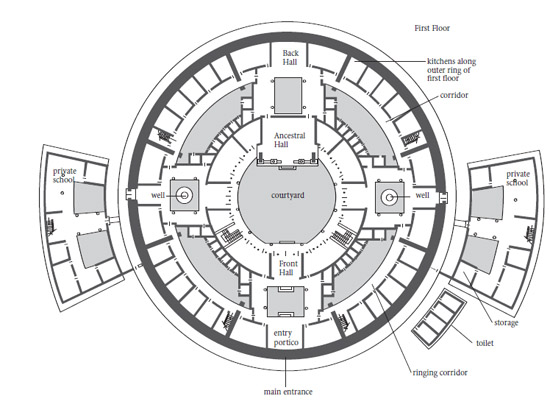

This perspective drawing captures the essential elements of Zhen Cheng Lou: a four-story round outer structure with a two-story inner ring connected to an Ancestral Hall; a large main entry and two smaller side entries; windows only on the upper two floors; and three outlying utility structures.

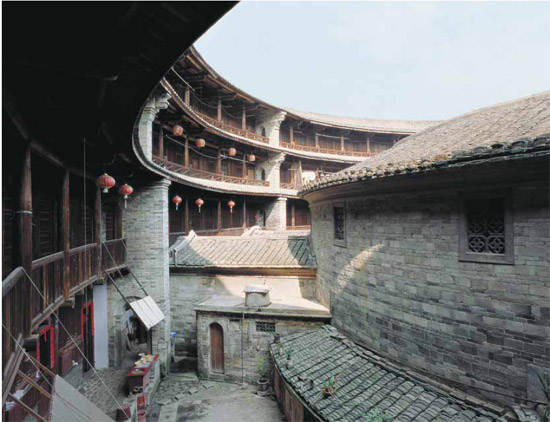

Zhen Cheng Lou or “Inspiring Success Tower,” one of a hundred tulou of various sizes in Hongkeng village, is a four-story circular fortified structure with windows only on two levels of the upper wall (see pages 18–19). Built in 1912 by Lin Xunzhi during an unsettled period as the Qing imperial dynasty ended and the Republic of China was coming into existence, the windows are embrasured—their side frames are angled within the thick wall so that the opening inside is wider than that outside—for increased security and to make surveillance from inside easier.

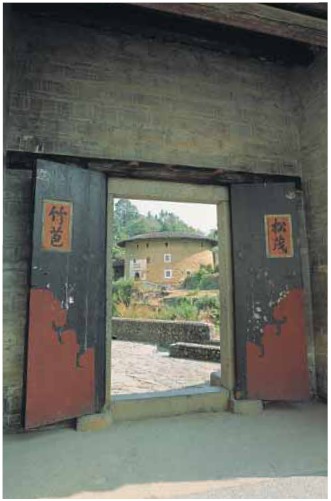

The path leading to Zhen Cheng Lou, as it does now, once did not lead directly to the gateway but instead approached at an angle from the side before turning sharply on to an elevated platform surrounding the structure. This zigzagging shows attentiveness to fengshui considerations relating to appropriate siting but also probably had defensive significance as well. Today, the area in front of the structure is much more open than it was even a decade ago, cleared in order to facilitate the needs of tourist photographers. The single entry gate into the structure is oriented slightly to the southeast and has the three characters “Zhen Cheng Lou” emblazoned above it. As with other fortresses, the massive stone entry portal leads into a gate hall, an entry portico or menwu, an area that is normally occupied throughout the day by women, children, and old men. Here they “guard” passage into their complex as they perform work like husking rice and preparing food to be cooked (or today selling postcards). Covered with a sheet of iron, the thick wooden doors are further secured when closed with a huge beam set horizontally into sockets.

Both photographs reveal the texture and massive character of the walls of tamped earth structures in southwestern Fujian. Only in recent decades with increasing levels of security have residents taken to excavating window openings in the lower portions of the walls.

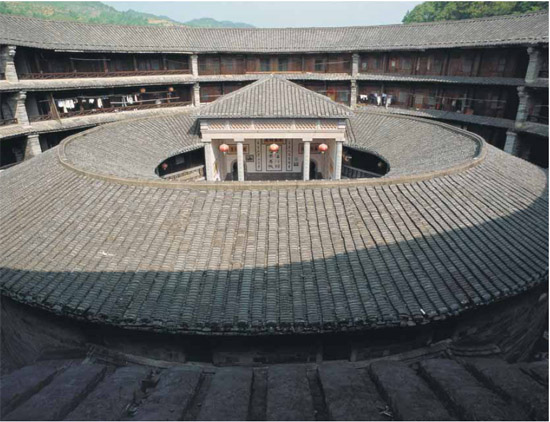

Swept by the asymmetrical arc-shaped shadow of the late autumn sun, the interior core of Zhen Cheng Lou reveals its striking three-bay Ancestral Hall with an inner circular core of utilitarian spaces covered by a tile roof.

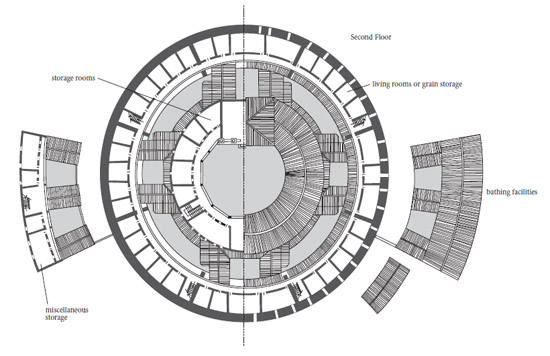

While in many similar structures, an open circular courtyard is found beyond the menwu, Zhen Cheng Lou has a secondary ring of structures surrounding a central courtyard. The division of space within the outer walls of Zhen Cheng Lou is apportioned equally with most rooms of similar size so that there are individual entries into each “apartment.” Closer examination reveals a carefully crafted auspicious design that, while not unique, is significant. Zhen Cheng Lou was artfully planned to express the Eight Trigrams or bagua, a cryptic divinatory text believed to have great symbolic power in Chinese culture and that is used in properly siting a dwelling. There are several tulou that are actually octagonal in shape with eight straight walls that intersect, but Zhen Cheng Lou is round on the outside while its interior living space is divided into eight clearly differentiated units to invoke the Eight Trigrams. Each of these eight units is separated from another by a tamped earth wall and then subdivided into three or six “bays” or jian, the common Chinese building unit, that are fronted by four linear courtyards that face the animal sheds. Several wells within the courtyard supply the residents with water.

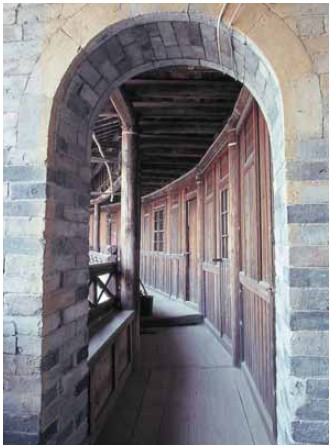

Brick walls placed perpendicular to the outer round walls help to buttress the structure. Within the building, wood dominates as the building material. Wooden floor joists are sunk into each of the tamped earthen walls of the upper three stories, while a wooden framework of interlocking mortise-and-tenoned pieces gives shape to rooms and verandahs.

This view between the two rings of structures reveals the abundant use of fired bricks for interior walls and partitions, which are then capped by fired clay roof tiles. Individual families have four-story “apartments” consisting of a series of rooms arranged vertically.

While the outer walls that ring Zhen Cheng Lou are of an earthen composition, the structural space within is all built of wood. Wooden floor joists for each of the upper three stories are secured deep into the tamped earth walls, and a wooden framework of interlocked pieces is assembled to support much of the weight of a heavy tile roof. Thin baked bricks are placed on top of the floorboards of the arcade around each level as a fire prevention measure. The two-story inner ring connects with a tall three-bayed Ancestral Hall with a four-sloped hipped roof, which itself is the focus for auspicious ornamentation. At the center is a nearly circular open courtyard, large enough for family ceremonies. This core area is connected to the outer structure by four roofed corridors that pass around four square skywells, two of which have wells.

A pair of symmetrical arc-shaped two-story structures lies adjacent to Zhen Cheng Lou, a combination that is rarely seen. Local lore refers to the pair as being symbolic of high position since they appear like the flaps of a traditional hat worn by officials during imperial times. One served as the location of a school for children of the Lin family, while extra space was used for storage and bedrooms for visitors.

Ru Sheng Lou

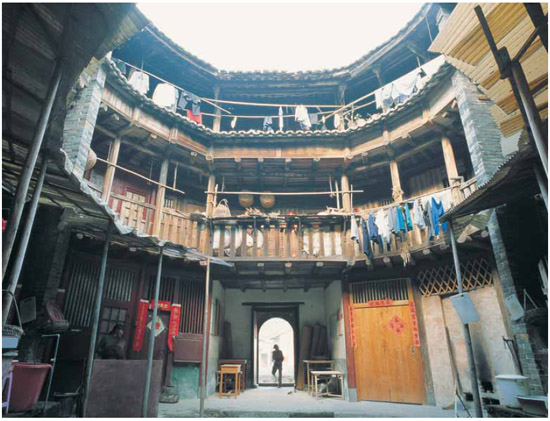

Among the smallest round earthen dwellings is one built more than a hundred years ago by a branch Lin family somewhat upstream in Hongkeng village. With an external diameter of 17.4 meters and an internal diameter across the circular courtyard of only 5.2 meters, its compact shape and size have given rise to the name Ru Sheng Lou or “Like a Sheng Tower,” since its form is said to evoke the Chinese canister-like volumetric dry measure for grain, called a sheng.

The single arch-shaped entryway is oriented somewhat towards the northwest, differing significantly from others in the village. Directly opposite the entry is the Ancestral Hall, which occupies a single central bay and juts out slightly into the round courtyard. Paved with stones harvested from the nearby stream, the courtyard is the center for daily activities because of the presence of a well and the sunlight that enters during the day. A pair of stairs leads to the two upper stories, which are framed in unpainted wood.

A fair question is, why round shapes when most Chinese structures are square or rectangular? In some areas, there was a clear transformative progression with square fortresses being supplanted by round ones. Once builders experimented with curvature, it took little time for circular structures to emerge from curved framing systems. For one thing, a circular wall is able to wrap approximately 1.273 more interior space than a square wall of the same length, according to Chinese calculations. Thus, constructing circular exterior walls as compared to straight ones saves scarce building materials. Within a circular structure, moreover, the wooden members used to frame interior living quarters can be standardized in dimension, thus reducing the level of carpentry skills needed to complete the project. The modularization of components with a circular roof eliminates the difficult joinery necessary to link the intersecting planes atop a square structure. Some observers also suggest that round shapes are more resistant than other shapes to earthquake damage and are able to deflect the strong winds of seasonal typhoons. In terms of social structure, residential space can be divided more equitably than is the case with a square shape. Doing so provides egalitarian division of assets and a spatial affirmation of an aspect of Hakka life that differs from the hierarchical associations so often seen in Chinese architecture. Using these criteria, the benefits are clear with larger structures even though little is gained by building a small round building in comparison to a small square one.

This plan of the first floor shows the division of the interior space into eight segments, a separation that has cosmological meanings associated with the Eight Trigrams. Much of the layout is symmetrical, including a pair of wells and side entries, corresponding skywells positioned throughout the building, stairways, and two wing structures. Only the toilet is not duplicated on both sides. A hierarchy of spaces is apparent from the entry straight through to the Back Hall.

This plan shows rooms on the second floor of both the outer and inner rings. Roofed passageways allow individuals to move freely across and around the structure even in the most inclement weather.

More than a hundred years old, Ru Sheng Lou is among the smallest round structures. It has an external diameter of more than 17 meters from outside to inside with little more than a five-meter-wide interior courtyard. This view is from the Ancestral Hall towards the only doorway. At ground level, the space is divided into twelve rooms, an Ancestral Hall, and an entry portico.

This view of the exterior of Ru Sheng Lou is from inside the gate of Fu Yu Lou, discussed earlier, which is immediately across the stream that passes through the village.