In the summer of 1996, the two of us were graduate students in psychology at the University of Western Ontario. We had known each other for about a year, but now, thanks to the occasional reshuffling of graduate student offices, we were sharing an office on the eighth floor of the university’s social science building. Before long, we found that we had a lot to talk about: both of us were fascinated by the study of individual differences—abilities, attitudes, interests, and especially personality traits.

The 1990s were exciting years for personality psychology. The field was recovering from the dark days of the 1970s and 1980s, when many researchers had given up on the idea that personality could be studied scientifically. And UWO was an exciting place to be studying personality: some of our professors, such as Sam Paunonen and the late Doug Jackson, were among the few who had been advancing the field of personality psychology even when it was out of fashion.

During those days, one of the most popular ideas in the field of personality psychology was that of the “Big Five” personality factors. According to this idea, the many hundreds of personality characteristics that make one person different from the next—traits from absent-minded to zestful, and everything in between—could be classified into five large groups, or factors. To summarize the personality of any given person, all you needed to know was that person’s levels of these Big Five personality factors.

Personality researchers had good reasons to be excited about the idea of five basic personality factors. From a practical point of view, the Big Five offered researchers an efficient way to summarize people’s personalities: measuring a few traits representing these five groups would give most of the information that could be gained—with much greater time and expense—by measuring people on all personality traits. And from a theoretical point of view, the Big Five promised to help reveal the meaning of personality: by identifying the common element of the traits in each group, researchers would gather some clues about what causes personality differences—along with some clues about why those differences matter in life.

So, here are the Big Five personality factors as they have been most widely known, with some examples of the traits that belong to those factors:

Extraversion (e.g., outgoing versus shy)

Agreeableness (e.g., gentle versus harsh)

Conscientiousness (e.g., disciplined versus disorganized)

Neuroticism (e.g., anxious versus calm)

Openness to Experience (e.g., creative versus conventional)

Now, keep in mind that these are five groups of traits. They’re not five types of people. (Really, they’re not types of people.) In principle, you could measure every person on each of the five personality factors, and each person would have five numbers to summarize his or her personality.

Back in our grad student days in the 1990s, the Big Five personality factors were a hot topic. This five-factor model was making it much easier to do systematic research about personality and its links with other aspects of life. Suddenly it seemed that researchers in every field of psychology wanted to understand how their concepts—from depression to job performance, from conformity to delinquency—were related to the Big Five factors of personality. One of the main reasons for this explosion of research was the development of a personality questionnaire that could measure the Big Five factors very accurately. This personality inventory, developed by Paul Costa and Robert McCrae, was beginning to dominate the field of personality assessment.1

Up in our office, we were following these developments with interest. Over lunchtime chats, we often discussed the idea of the Big Five. We wondered about the meaning of the factors. Why should these be the basic elements of personality, and why were there exactly five of them? And we talked about the ongoing arguments between supporters and opponents of the five-factor model. To get a grasp of the issues being debated, we did a lot of reading to find out exactly where the Big Five came from in the first place.

One important point, we soon learned, was that no one had invented the Big Five factors—no one had simply decided that personality traits should be divided up into these five large groups. Instead, the Big Five had been discovered by researchers who systematically studied how the many hundreds of different personality traits were all related to one another.

The first step in discovering the basic factors of personality is to generate a complete list of common personality traits. To do this, researchers search the dictionary and select all of the personality-descriptive adjectives they can find, eliminating only very rare or obscure terms. The next task is to measure many people on these personality traits. This is typically done simply by asking many persons each to rate his or her own level of each trait, on a scale from (say) 1 to 5 or 1 to 9. (Alternatively, the researchers sometimes ask each person to rate the trait level of some closely acquainted person.)

Now, if researchers needed really accurate measurements of any given personality trait, it would be better for them to use a well-constructed personality inventory (see, for example, the HEXACO–PI–R in the Appendix). But the aim here is simply to get some rough measurements of several hundred traits, to find out how much each trait is related to every other trait. And as we’ll mention in Chapter 5, people are usually pretty frank in rating their own personalities, at least when responding anonymously as part of a research project. They don’t have much incentive to exaggerate good points or minimize bad points.

Once researchers have obtained people’s ratings of their personality traits, the next step is to calculate how much each trait goes together—how much it correlates—with every other trait. With these correlations, they can find a few main groups of correlated traits, using a technique called factor analysis. (The concepts of correlation and factor analysis are explained in Box 2–1.)

BOX 2–1 Correlations and Factor Analysis

The correlation between two traits tells us how much those traits go together in a group of people. Consider these examples.

People with higher-than-average levels of Liveliness usually have much higher-than-average levels of Cheerfulness, and usually have somewhat lower-than-average levels of Shyness, but they are about equally likely to be above or below average on Organization.

In this case, we say that Liveliness shows a strong positive correlation with Cheerfulness, a weaker negative correlation with Shyness, and roughly a zero correlation with Organization.

Notice that the correlation is based on people’s relative levels of each trait, in comparison with everyone else. For most personality traits (and for some other psychological traits, such as abilities), the numbers of people above and below the average are about the same. A few people are far above the average and a few are far below, but most are fairly close to the average.

The correlation between two traits is expressed as a number that can range from –1 to +1. As a general guideline in personality research, correlations (positive or negative) of .10 are considered small, .30 medium, and .50 large. When a correlation is much higher (say, .70 or .90), it usually involves two traits that are very similar, or two measurements of the same trait.

When calculating the correlation between two traits, it’s a good idea to measure lots of people—ideally, several hundred or more. In a small group of people, the correlation might be much higher or lower than its real value for the whole population, just by fluke.

Factor analysis is a statistical technique that sorts traits into groups according to the correlations among the traits. Factor analysis identifies traits that correlate with one another and puts them into the same group (or “factor”). Likewise, factor analysis puts traits that are uncorrelated with one another into different factors. The word “factor” originally meant “maker,” because the factor represents some influence that makes its traits correlate with each other.

Note that a factor can include some traits that are negatively correlated with other traits in that same factor. When this happens (and it usually does happen), we say that the factor has two opposite sides (or poles). The idea is that opposite traits still involve the same underlying dimension. Here’s an example: even though “fast” and “slow” are opposite, they both refer to the same dimension—speed—so it makes sense to put them at opposite sides of the same group, and not into two unrelated groups.

The results of factor analysis aren’t always perfectly simple. Some traits don’t fit neatly within one factor; instead, they might belong partly to one factor and partly to another. And it isn’t always obvious exactly how many factors there are: the factor analysis can tell us the best way to classify traits into any given number of groups, but it doesn’t always give us a clear answer about what is the true number of groups. These trickier aspects of factor analysis will come into play a bit later in our story.

Researchers started doing these factor analyses of personality traits as early as the 1930s. By about 1960, they were beginning to notice a pattern: when personality traits were measured in any given sample of people—from college sorority students to air force officers—the factor analyses indicated five groups of traits.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Lewis Goldberg undertook some much more systematic studies of personality traits. He studied larger sets of personality traits than previous researchers had done, and he measured these traits in larger samples of people. His results showed five large factors—essentially the same ones as those reported back in the early 1960s—and no others. The Big Five personality factors, as Goldberg called them, were no fluke.2

But the Big Five weren’t yet the final word on the question of personality structure, for two reasons. First, the Big Five findings that we’ve described above were based on studies of the English language alone: no one knew whether the same factors would be found if the personality-related words of other languages were examined. And second, the Big Five findings were based on relatively short lists of traits; in the days before high-speed computers, longer lists could not be analyzed. If much larger sets of personality traits could be analyzed, more than five factors might well be found.

Just around the time we moved into our new office, we were reading about the results of new investigations of personality traits—investigations that tested how well the Big Five system worked in other languages and with larger sets of personality trait adjectives. In Europe, various research teams were conducting factor analyses of personality trait adjectives in several languages—Dutch, German, Hungarian, Italian, and Polish. With the recent increases in computing power, those researchers had been able to factor-analyze sets of several hundred adjectives. For the most part, the results of these studies suggested that the Big Five factors really were the basic elements of personality: in each language, the researchers found five factors that matched the familiar English-language Big Five rather closely.

One day when we were discussing these findings, we began to wonder whether the Big Five would be found even in non-Western cultures. So far, all of the factor-analytic studies of personality traits had been conducted in Europe or North America, which left open the possibility that the Big Five might be found only in Western cultures. By conducting a similar study in a non-Western culture, we might find out whether the Big Five really reflected something universal about human personality traits. Fortunately, we were in an excellent position to do this kind of research: one of us was a fluent speaker of Korean, born and raised in Seoul, and had a former professor who might be willing to help us out. We decided to give it a try, and look for the Big Five factors in the personality trait adjectives of the Korean language.

In 1997, we began collecting data from students at Sung Kyun Kwan University in Seoul, South Korea. More than 400 students rated their own personalities on a set of about 400 familiar Korean personality adjectives. On the day we received the data file from our Korean collaborator, we hurried downstairs to the graduate student computer lab and began doing the factor analyses. We waited anxiously as the computer churned through the calculations—in those days, it still took a few minutes to run a factor analysis of so many traits. Would we get results that resembled the Big Five? Would the results make any sense at all? When we made our first quick inspection of the results, we were relieved—and fascinated—to see that the Korean personality adjectives fell into five factors very similar to those found in Western countries. We soon began writing a manuscript about the results, eager to let the personality world know that the Big Five factors weren’t just a Western phenomenon.

While we were writing up the results of our Korean personality project, we looked a little more deeply into our data set, by running factor analyses with different numbers of factors. When we had first received the Korean data, we simply wanted to see the results for five factors, so that we could compare the Korean five factors against the usual Big Five. But now we wondered how the Korean adjectives would sort themselves out if we asked the computer to sort them into more than five groups. So we checked out the results for six and seven and eight factors. (Remember from Box 2–1 that when you do a factor analysis, the number of factors isn’t always obvious; also, you can examine the results for different numbers of factors.) To some extent we were just procrastinating, taking a break from the chore of writing the manuscript. But we were curious to see what would happen.

When we looked at the results for eight factors or seven factors, some of the categories were very small, consisting of only a few adjectives. But the results for six factors were much more interesting. In addition to factors that looked like the Big Five, there was a sixth factor that was fairly large and easy to interpret: on one side, it had adjectives (translated from Korean) such as truthful, frank, honest, unassuming, and sincere; on the opposite side, it had adjectives such as sly, calculating, hypocritical, pompous, conceited, flattering, and pretentious.3

At first we were surprised to see that there was a large sixth factor. The previous studies of the English personality lexicon had found only five; no sixth factor could be recovered. But we wondered whether this sixth factor might be found in languages other than Korean, so we started checking the results of some recent lexical studies conducted in various European languages. Now, most of these studies had focused on whether or not the Big Five would be recovered. In a few studies, however, the authors did mention briefly the results they found when they examined six factors. In each case, they found a factor that was defined by terms such as sincere and modest versus deceitful, greedy, and boastful—much like the factor that we observed in our Korean study. As for the reports that didn’t mention anything about a six-factor solution, we contacted the authors directly to find out.

We weren’t sure that those researchers would respond to our request for additional analyses, but we were pleasantly surprised. A Polish researcher, Piotr Szarota, replied within hours, and so did an Italian researcher, Marco Perugini. In every study, the six-factor solutions were similar, consisting of five factors roughly similar to the Big Five, plus another factor that suggested “honesty and humility” versus their opposites.

We wrote a manuscript about our Korean findings and published it in the European Journal of Personality. Over the next few years, we followed up this research with a lexical study of personality structure in the French language, this one in collaboration with our fellow graduate student, Kathleen Boies. Our French study, conducted in Montreal, revealed essentially the same six factors as those found in Korean and in European languages.4

All of these findings made us wonder whether the same set of six factors might be found in the English language too. Remember that in the early English lexical studies, researchers had very limited computing power at their disposal, so they couldn’t analyze hundreds of adjectives all at once. We decided to revisit the English language to find out whether all six factors could be found in analyses of larger sets of adjectives. In one study, Lew Goldberg generously suggested that we reanalyze some data that he and his colleague Warren Norman had collected.5 In another study, we started with our own list of common English personality adjectives.6 In both cases, we found basically the same six-factor solution as observed everywhere else.7 By now we no longer had any doubts: there were six major dimensions of personality.

Now, you might be wondering whether there might be some set of seven personality factors (or eight, or nine …) that are found in similar form across these various languages. We wondered this too, but we found no other personality factors that were consistently recovered. Apparently, there are only six big categories of personality traits.

We now realized that the Big Five system should be revised to accommodate the new results. In some sense, we were too late, because the five-factor model had already become widely accepted by other researchers. Yet these new results indicated that there were six personality factors, not five. So we decided to propose a new model for personality traits, one that would preserve the key features of the Big Five while also incorporating these consistent new findings.

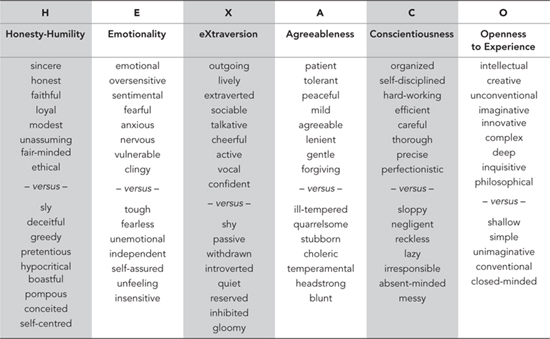

We named this new framework the HEXACO model of personality structure. The acronym “HEXACO” was neatly convenient, because it indicates both the number of the factors (the “hexa” prefix) and the names of those factors: (H)onesty-Humility, (E)motionality, e(X)traversion, (A)greeableness, (C)onscientiousness, and (O)penness to Experience.8 We’ve listed in Table 2–1 some personality trait adjectives that typically belong to each of the six factors, both at the high end and at the low end. In the next chapter, we’ll describe these six factors in more detail.

TABLE 2–1 Personality-Descriptive Adjectives of Six Factors Observed in Lexical Studies of Personality Structure