Think of your spouse and your best friends. For any one of these people, you can probably think of some similarities and some differences between his or her personality and yours. But are there some personality traits that you have in common with most—or even all—of those persons?

In this chapter we examine the ways in which people are similar in personality—and the ways they think they’re similar in personality—to their friends and spouses.

Before we get to personality characteristics, let’s consider some other ways in which you’re probably pretty similar to your friends and spouse. We bet that for the most part, your friends and your spouse are similar to you in characteristics such as age, educational level, religious affiliation (or lack thereof), and ethnic background. Any one of those people may differ from you in some of those ways, but on the whole you probably have more in common with them, demographically speaking, than with the average person.

Why is this? One important reason is that when people go to work or school or church or social gatherings, most of the people around them have backgrounds similar to their own. People naturally end up with friends and spouses who share their backgrounds. This happens even if people aren’t trying to select social partners who are similar to them.

But most people are even more similar to their spouses and friends—at least in some ways—than to the average person in their broader social surroundings. One example of this is physical attractiveness: on the whole, spouses are more similar in physical attractiveness than two people picked at random would be. This is true even though we can all think of some couples in which one partner is much more attractive than the other.

Some researchers have studied how it is that romantic partners tend to be similar in physical attractiveness. One study followed more than 120 couples over a period of nine months and found that any given couple was more likely to break up when the partners were mismatched for physical attractiveness.1 Moreover, the more attractive partner of a couple had more opposite-sex friends than did the less attractive partner, which suggests that the more attractive partner had more options for alternative partners and hence a stronger incentive for ending the relationship. Apparently, mate selection is something like a competitive marketplace where people tend to end up with partners whose attractiveness is similar to their own. Of course, attractiveness is not the only characteristic that people desire in a mate, so high levels of other characteristics can compensate for lower attractiveness, and vice versa. Still, physical attractiveness is apparently an important part of a person’s overall “mate value” as perceived by others.

Physical attractiveness is a characteristic that pretty much everyone desires in a mate—other things being equal, most people want a mate who is physically attractive. But not all characteristics work this way. For some traits, there is no universally agreed “better” direction, and for most of those traits people prefer a mate who is similar to themselves. Consider religiosity: religious people want religious mates, and people who aren’t religious want mates who aren’t religious either. You’ve probably noticed that hard-core atheists rarely marry religious fundamentalists. Such a marriage would make good material for a television sitcom, but it probably wouldn’t work. Researchers consistently find that in most marriages, spouses are similar in their level of religiosity.2 And of course, highly religious people prefer highly religious mates of the same religion.3

When it comes to the matching of romantic partners, political attitudes are a lot like religious beliefs. People with left-wing attitudes tend to pair off with each other, and so do people with right-wing political attitudes. Couples such as the now-separated Maria Shriver and Arnold Schwarzenegger—she a Democrat, he a Republican—are much less common than couples who have similar political orientations. The similarity between spouses for political ideology is almost as strong as for religiosity.

BOX 6–1 Why Are Spouses Similar in Beliefs and Attitudes?

If spouses are similar in their beliefs and attitudes, does this really mean that like-minded people tend to find one another—in other words, does it mean that spouses were similar even before they met? The matching of similar spouses could happen in some other ways. For example, the viewpoints of one or both spouses may tend to converge over the years. (Even if people were paired off at random, you might still expect partners to become more alike as the months and years go by.) Or perhaps relationships are more likely to break up when the partners’ views are just too far apart. (Again, even if people were paired off at random, you might still expect the most durable relationships to be those between people who happen to have similar beliefs and attitudes.)

Some research has tested these possibilities. In one study of over 500 couples, the participants completed surveys of religiosity and political attitudes on occasions 17 years apart.4 The researchers found that the spouses were just as similar when they were first surveyed as they were many years later. This means that there wasn’t any gradual convergence between the spouses as their marriage progressed. Also, the spouses who had divorced or separated—about one-sixth of the sample—were just as similar as the spouses who stayed together. So it wasn’t the case that there were lots of ill-fated relationships between partners with opposite viewpoints; instead, such couples had rarely even formed in the first place. This isn’t to say that marriages between partners of strongly opposing attitudes would necessarily work. Probably the reason why there are so few couples of this kind is that people usually rule out such relationships as unworkable before they even get started.

So much for attitudes. But what about personality? Are spouses similar in personality traits in the sense described in this book? Or do opposites attract? Or is matching completely random? And—in case we become too narrowly focused on romantic relation-ships—what about friends? Do we generally choose friends whose personalities are similar, on balance, to our own? Or do we pick friends who are opposite to us in some aspects of personality, as if we were seeking friends whose personalities would complement our own?

In the early 2000s, we did a series of research projects that gave us a great deal of interesting data on these questions. As mentioned in the previous chapter, we collected lots of personality data from pairs of closely acquainted people—usually pairs of close friends, sometimes boyfriend/girlfriend couples. As you’ll recall, we found fairly high correlations between self-reports and observer reports of the six personality factors. This meant that the students tended to agree with each other in their (independent) assessments of each other’s personalities.

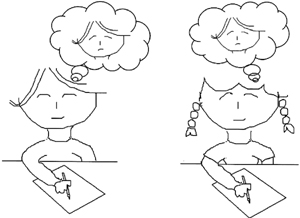

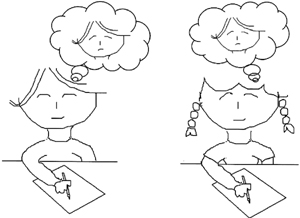

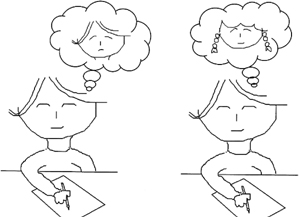

Eventually, we realized that these data could also be used to examine the topic of similarity in personality between friends or romantic partners. Remember that in these studies, the participants in each pair completed the personality inventory twice: once to describe their own personality, and once to describe the other person’s personality. Suppose that two friends, Jack and Jill, are participants in our study. First Jack and Jill each provide self-reports using our personality inventory; then each provides observer reports of the other person using the same inventory. To find out how much the self-reports on a given trait agree with the observer reports, we simply compare Jack’s self-reports with Jill’s observer reports about Jack, and vice versa (see Figure 6-1).

But if we want to know how similar our participants are on a given trait, we will instead compare Jack’s self-reports and Jill’s self-reports (see Figure 6-2). This is the same similarity we were talking about earlier in this chapter—how similar two friends are in a given personality trait.5

And finally, if we want to know how similar our participants seem to think they are to each other on a given trait, we compare Jack’s self-report with Jack’s observer report about Jill, and vice versa. These correlations tell us how similar Jack thinks Jill is to him, or how much similarity is implicitly “perceived” or “assumed” by Jack (see Figure 6–3). That is, even though we haven’t explicitly asked Jack about how similar he and Jill are, these correlations indicate how much his report about Jill’s personality resembles his report about his own personality.

FIGURE 6–1 Self/Observer Agreement

FIGURE 6–3 Perceived Similarity

We searched the personality literature for any previous investigations on similarity and perceived similarity. But we couldn’t find many, and the few that existed hadn’t found much similarity in personality between friends, or even between spouses, and hadn’t found much assumed or perceived similarity either. So we realized that we could learn something new from our data.

When we looked at the correlations between the self-reports of the two friends of each pair, we found that the friends were usually somewhat similar in two of the HEXACO factors: H and O. The degree of similarity was only modest: the correlations were about .25 for both factors.6 But for the other four factors, there was very little similarity.

What this meant was that the more genuine and unassuming university students (those high in H) tended to find each other as friends—at least at a somewhat higher-than-chance level—and that the more devious and pretentious university students (those low in H) tended to do the same. Likewise, the more inquisitive and complex university students (those high in O) also tended (somewhat) to attract each other as friends, as did the more conventional and unimaginative university students (those low in O). Maybe this doesn’t sound so surprising, but what makes these results so interesting is that for the other four personality factors, this tendency was much weaker. For those other dimensions, it was as if the friend pairs were forming almost at random.7

The results were even more striking when we examined the amount of perceived similarity between friends, by checking the correlations between people’s self-reports and their observer reports about their friends: people perceived their friends as being quite similar to them in the H and O factors, with correlations around .40 (a bit higher for H and a bit lower for O). In other words, the perceived similarity between friends for H and O was even greater than the actual similarity. But for the other four factors, there was no such perceived similarity.

Putting these two sets of findings together, we can say that friends are somewhat similar in their levels of H and O—but not as similar as they apparently think they are. To some extent, friends are correct in perceiving some similarity between themselves in the H and O factors. But they also tend to perceive more similarity than there really is. And for the other four factors, the friends (on average) are neither similar nor opposite, nor do they see each other as similar or opposite.

These findings still left us with a question: Why these two factors? Why should friends be similar (and perceive themselves to be even more similar) on these two aspects of personality, and only on these two? A couple of years later, we had some ideas and a good opportunity to test them. With our graduate students, Julie Pozzebon and Beth Visser, we began a study of people’s “personal values” in relation to the HEXACO personality factors. Personal values is one of the few topics in psychology that can be said to be uniquely human. Researchers can study learning, or perception, or motivation, or intelligence, or even personality in many other non-human animals. For example, there are many scientific reports about “personality” traits for such animals as chimpanzees, dogs, various kinds of fish and birds, and octopuses. Apparently, the personality traits of individuals in those kinds of animals can be measured reliably; furthermore, the differences between individuals are stable across time and are genetically inherited. By contrast, humans seem to be the only animals to have values—ideals about which goals ought to matter in life. By investigating values, we would be able to test our ideas about why some personality traits exhibit similarity and perceived similarity between friends.

What are the main differences among people in their personal values? Researchers have found two broad dimensions: the first factor represents the relative importance one places on individuality and novelty as opposed to conformity and tradition; the second represents the relative importance one places on equality and the welfare of others as opposed to one’s own power, wealth, and success.8 In other words, there are two main ways in which people can differ from one another in their values: one way is that some people prefer independence and change whereas others want to respect authority and preserve tradition; the other is that some people emphasize caring and sharing whereas others are concerned only with their own gain.

You can probably predict how these two dimensions of values were related to the major dimensions of personality: the first was related to the O factor, the second to the H factor. Apparently, people’s values are a function of their personalities, but mainly just these two aspects of personality, as the relations with the other four personality factors were weak. So we had finally found an important feature shared by H and O but not by the other four HEXACO factors: the H and O factors, much more than the others, underlie our choices regarding which goals are worth pursuing throughout one’s life.

But if the link with values is what explains why friends are similar (and see themselves as similar) in H and O, we should also find similarity (and perceived similarity) for the values dimensions. We checked this out, and sure enough, the pattern of similarity and perceived similarity for the value dimensions was the same as we had found for the H and O factors. People prefer to associate with those who have similar values, and this is probably because these values are so important to one’s sense of identity. We define ourselves, in part, in terms of how we think people should relate to one another and to the broader society. Because our personal value system is an important part of who we are, it’s an important element in forming our friendships and romantic relationships.9

We’re not saying that most people consciously decide to start or to continue their relationships by thinking, “Well, this person appears to have values similar to mine, therefore I will choose this person as my friend.” Not many people operate in this way. Our point instead is that people simply find that they like each other better when they’re on the same wavelength about the things that matter in life, even though they don’t necessarily realize that this is influencing their liking for each other.

This explanation also fits neatly with another finding about perceived similarity. People should see their friends or romantic partners as similar to themselves, because those are close, meaningful relationships. In contrast, people shouldn’t see so much similarity in other people—say, co-workers or classmates or neighbours—with whom they are fairly well acquainted but not particularly close. And people shouldn’t see much similarity either in people whose personalities they can observe but with whom there isn’t any relationship at all, such as fictional characters. We tested these ideas out in a couple of studies. In the first, we found that the level of perceived similarity in H and O was much lower for co-workers and classmates and neighbours than for close friends and romantic partners. In the second, we found that there was no perceived similarity at all when we asked our participants to report on the personalities of two familiar television characters (specifically, Ross and Rachel from Friends, a popular US sitcom of the 2000s).

All of these results have an interesting practical implication. According to an old Korean saying, we should “look at the friends to learn about the person.” Our results suggest that this proverb is true—if we mean the H and O factors of personality, and the values associated with those factors. We could probably get a fairly good idea of a person’s levels of H and O by averaging that person’s closest friends’ levels of each factor.10 And we could get an even more accurate idea by averaging the levels of H and O that the person attributes to his or her friends.

The links between personality and values help us understand why friends tend to be similar—and to perceive each other as similar—in the H and O factors of personality. Those results also open the door to a couple of other domains in which the H and O factors are implicated: politics and religion. These are the topics of the next two chapters.