3. Designing a Project That Works

Having arrived at a problem, now you must make decisions about what you can accomplish, given your available resources. In particular, you need to think about the primary sources you’ll need to answer your questions and solve your Problem, as well as the resources you’ll need (including time!) to put together a project.

The issues this chapter deals with are both conceptual and practical: What are primary sources? Which ones can you actually access? How can you discover the full potential of a source related to your topic, or look beyond the obvious questions one might ask about a source to arrive at something original? How can you use such sources to pinpoint your Problem? What arguments can you make with your sources? How many sources can you acquire? How much time will you have to analyze them? How should you design your project, given your personal work habits, material constraints, or deadline?

Getting from a problem to a project involves more than just logistics. Project planning involves self-assessment and visualization. What model or type of project is most suitable for you? What do you want the finished product to look like?

Primary Sources and How to Use Them (or, Fifty Ways to Read a Cereal Box)

Sources are essential to original research, so figuring out how to identify, evaluate, and use them is a crucial practical consideration. Researchers conventionally divide sources into two general categories: primary sources and secondary sources. Research guides typically define primary sources as “original” or “raw” materials. They are the evidence that you use to develop and test claims, hypotheses, and theories about reality. Primary sources vary based on one’s field of study. For historians, primary sources tend to date to the period of focus, whether they are written documents, like letters and maps, or any other type of physical object. Anthropologists might rely on oral testimony, or audio recordings. In fields such as literature or philosophy, primary sources are usually texts.

Most research guides define secondary sources along similar lines. The Craft of Research (4th edition) defines them as “books, articles, or reports that are based on primary sources and are intended for scholarly or professional audiences,” and which researchers use to “keep up with developments in their fields” and to “frame new problems” by “challeng[ing] or build[ing] on the conclusions or methods of others” (p. 66).

While we largely agree with these definitions, we also want to reinforce a point well known to veteran researchers about the dangers of defining “primary” and “secondary” sources in terms of absolutes. We would advocate not thinking of primary sources solely as old objects or documents found in archives or online repositories, and secondary sources as studies that “use” primary sources the way one might process raw materials into finished products (to extend the above metaphor). If the term primary sources conjures up images of weathered manuscripts, sepia-toned photographs, shards of ancient pottery, or clippings from a centuries-old newspaper, it’s time for a shift in perspective.

Absolutist definitions of sources get in the way of the process of identifying primary sources and asking research questions, for two reasons:

- 1. Any source can be primary, secondary, or not a source for your project.

- 2. A source’s type is determined solely by its relationship with the questions you are trying to answer, and the problem you are trying to solve. A source is never inherently primary or secondary.

A more accurate definition of primary source would be the following: a source that is primary with respect to a particular question.

Notice how our definition recasts the “primary-ness” of a given source in relative terms.

Take, for example, a college-level US history textbook published in 2019. According to an absolutist definition of sources, there can be little doubt that this is not a “primary” source, since it draws on multiple works of scholarship. Someone who wants to learn about the First Continental Congress or the root causes of the American Civil War would refer to this book not as a primary source produced contemporaneously with the events in question, but as a secondary source that synthesizes historical arguments based upon sources, both primary and secondary.

But what if their question was not about the First Continental Congress directly, or about the causes of the Civil War, but about the history of textbooks themselves, or the history of how the American Civil War has been presented in American higher education in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries? What kind of source is this 2019 book now? Suddenly, a book that by all accounts should be considered “absolutely secondary” has become “primary,” despite the fact that it was published recently. Under these circumstances, this book from 2019 would show up in your bibliography amid other relevant primary sources: perhaps college textbooks from 1905, 1923, 1945, and so forth. Perhaps you might have access to the personal papers of the textbook author, or the possibility of interviewing the scholars and editors who were responsible for the 2019 work. Perhaps you might have uncovered a repository of course syllabi from a single university, which would enable you to examine the ways in which university courses explained the Civil War during, say, the immediate aftermath of World War I, or the lead-up to World War II, or during the height of the civil rights movement.

Let’s take this one step further. Just as the same source can be “primary” or “secondary,” depending upon context, so too can the same source be “primary” in dramatically different ways. The very same source can show up in the bibliographies of strikingly different research projects, and can be used by different authors to pose dramatically different kinds of questions.

Imagine that, in your database searches, you encounter a cereal box from the 1960s.

You’re not sure why this particular image intrigues you, but as you know well by now, “not knowing why” is entirely OK. Somehow, this source feels “primary” to your research interests, and so you trust your instinct and set out to figure out what questions it might help you answer.

Here you face a decision: how you treat this source will lead you down either a narrow path or a broad avenue of potential research questions.

The narrow route is to jump to the obvious candidates: questions about food culture, or perhaps about advertising or consumer culture. After all, you think to yourself, this is a box of cereal, and so the questions we would want to ask should obviously pertain to things like food, right?

You’re thinking yourself into, well, a box.

Remember: as a primary source, a box of cereal can be “primary with respect to” countless questions that have nothing to do with food per se. Let’s consider for a moment all of the different ways that a researcher could “read” a box of cereal. Or, to put this differently, let’s brainstorm for a moment different kinds of research projects that might conceivably include this source—a 1960s cereal box—in a bibliography or list of sources.

Let’s even go one step further and brainstorm what other primary sources this cereal box might end up “working alongside,” depending upon the particular research project in which it appears.

Based on what we come up with, let’s then give a name to the genre of questions we’re asking, on the assumption that it might be connected to an underlying problem.

The rows in the table 4, while numerous, offer only a sample of the different directions one’s research could take based on a single primary source. The key here is that when a source is unquestionably “primary,” the question still remains, Primary how?

Table 4. THE CEREAL BOX CHALLENGE: HOW TO QUESTION PRIMARY SOURCES

|

What I notice about the source |

Questions/concerns I might have |

The very next primary source I might want to find |

Broader subjects and/or genres of questions that might be related to my problem |

|---|---|---|---|

|

The various codes found on the box (e.g., printing codes, shipment codes, or for later cereal boxes, bar codes) |

Who uses these codes? Why are they positioned where they are on the box? How are they read or decoded? When did cereal boxes start to have such codes? |

Materials related to laser scanning and its application to logistics (consumer, transportation, postal system, etc.) |

Technology Supply chain logistics History |

|

The “Nutritional Facts and Recommendations” on the side of the box |

How are these facts and recommendations generated? By whom? |

Early medical and public health treatises on recommended daily food intake, materials on the discovery/invention of the concept of the calorie |

Biopolitics Standard measurements of energy and nutrition Government-industry relations |

|

The “storytelling” one often finds on the back of the box |

What did the producers or consumers of this product want it to say about the world? About consumers? About the company? Have the stories appearing on the backs of cereal boxes changed much over time? How about by type of cereal (e.g., sugar cereal vs. “healthy” cereal)? |

Other kinds of consumer packaging in which stories are told (children’s toys, exercise equipment, health and beauty products, etc.) |

Stories, narratives, discourses Times: Future and past |

|

The shape, size, and dimensions of the box |

Why does the box have this weight and size, when assembled or pre-assembled? Where is the box stored or held? at various stages of the delivery process, and for how long at each stage? How does it get from where it was made to where it was intended to go? How many boxes are in a shipment? |

Materials connected to the early history of containerized shipping |

Transportation Logistics Global capitalism |

|

The typefaces used on the packaging |

Why are some typefaces larger than others? How were the fonts chosen? Which possibilities were considered and rejected? |

Sample printed matter using low-cost, mass-produced paper stock, like telephone books, tabloid newspapers, psychological warfare pamphlets, etc. |

Typography Design history Hierarchies of design |

|

The color palette and symbols used on the package |

What are the primary considerations influencing the color palette? What do the symbols on the box represent? |

An advertising agency’s internal report on how colors affect consumer behavior, circa 1960s Other products made by the same company |

The psychology of color |

|

The 4-color printing guide hidden under the top flap |

Why is this design element positioned so that it cannot be seen in the store? Why is it on the box? How is it used? What other design elements are meant to be “invisible” to the consumer? |

Other consumer products or food products containing hidden designs on the packaging |

Machine-driven design Invisibility |

|

The “Best If Used By” date |

How is the expiration date calculated, and by whom? Does it appear on boxes of this cereal distributed in other countries? |

FDA regulations on food expiry calculations and consumer notifications |

Food safety Government regulatory regimes (national/international) |

|

The paper or cardstock used to make the box itself |

Which type(s) of tree is used to make the paper/cardstock? Where was it produced? How many trees per year were used to package this product? Is this (still) the industry standard? |

Other material objects produced using wood- and wood-pulp-based products |

Environmental history Forestry |

|

The glue used to seal the box, and the interior pouch |

What substance is the glue made from? Who made it? How was the adhesive chosen? How do most consumers open it? How much of the product do the producers expect to go bad before it can be consumed? |

Company R&D records on consumer habits Contracts with packaging vendors |

Chemistry |

|

The tab used to close or open the box |

How would the box be used? Which designs were considered but rejected? |

Other food products requiring repeated unsealing and resealing |

Durability Utility |

|

The archival box or container in which the cereal box is preserved |

How and why did this box come to be preserved? Who preserved it? How? Where? Was it preserved by accident, or intentionally for some specific purpose? |

Programs from annual meetings of the Society of American Archivists |

Archiving Determinations of cultural/historical worth Museology |

|

The price tag |

How much did this box of cereal cost? How and where was the price advertised? Was the box of cereal cheap, of average cost, or expensive for US consumers in the 1960s? What was the item’s availability? How did the price compare to the production and distribution costs? How much profit went to the producer versus the wholesaler versus the retailer? |

Archives of historical grocery stores and food producers that enable one to chart fluctuations in the cost of basic consumer goods |

Economic history Demographics Pricing strategies |

Mastering this method of dealing with primary sources will enhance the originality of your research. You will never again take a primary source at face value, or fall into the trap of asking only obvious questions. You’ll always be thinking “outside the cereal box.”

Connecting the Dots: Getting from Sources to Arguments

Now you have a primary source in front of you, maybe several. Now what? What do I do? How do I make a “thesis-driven argument” out of this source? Where do I begin? What should I take notes about?

All fair questions. And not the only ones.

Your methodological challenges are both practical and ethical:

- 1. How many primary sources, and which types of primary sources, are enough to do my research?

- 2. How can I evaluate the reliability or usefulness of sources?

- 3. How do I identify and exclude irrelevant sources?

- 4. How do I determine how my sources relate to one another?

- 5. How do I use various sources to make an argument, or express my degree of certainty or doubt about the argument I am using these sources to make?

That’s quite a barrage of questions, so let’s take a moment to think about how to connect the dots.

When we’re young, many of the puzzles we solve come in a box or in a book. They were created by other people and come to us in the form of prepackaged games: word searches, jigsaw puzzles, anagrams. Someone else already knew the answers, and then crafted a puzzle for us, whether to test our intelligence or to give us fun pastimes.

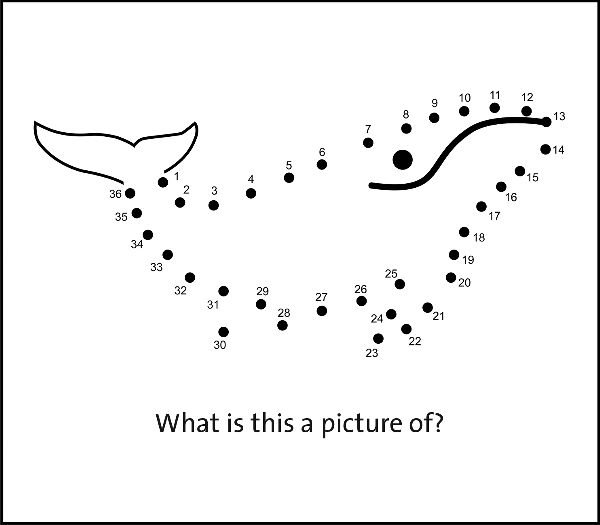

Remember the game Connect-the-Dots? On the page is a set of dots, each dot accompanied by a number, and the puzzle-solver draws a set of straight lines linking dot 1 to dot 2, dot 2 to 3, and so forth. After connecting all fifty or so dots, the secret image is revealed. In some cases, the image is the answer to a question, like “What is the biggest animal on earth?”

What if, instead of a connect-the-dots puzzle like that, you were presented with one that looked like this:

You see the issue here: you can draw an infinite number of lines through a single point (i.e., a single source), and this means that practically any picture—any argument, that is—can be made when based on only one source.

Even with two points, or three, the puzzle is overwhelmingly unrestricted.

How do you connect the dots when there’s only one dot to connect, or even only a few? How do you begin to chart out interpretations and arguments—the lines of reasoning that connect the dots—when you are just at the very beginning? What if you have only one, two, or three dots to work from? As eager as you may be to make headway in creating “a thesis-driven argument,” how can you possibly do so at this stage?

You can’t, and you shouldn’t try to.

In the early stages of research, faced with an unlimited number of potential questions and interpretations, any attempt to connect the dots rapidly spins out to infinity. The puzzle is unsolvable. An infinite number of lines—for the researcher, narratives and interpretations—can pass through such a small number of “dots,” or sources.

Yet the lesson here is not just that you need an adequate number of sources to connect the dots of a good argument. It’s more fundamental than that.

Over time, we discover that puzzles no longer come to us prepackaged and ready to solve. To the contrary, the main challenge becomes not solving, but creating puzzles that are nontrivial, not preordained, open-ended, and significant (no matter what the answer ends up being). In order to create puzzles, we need to be able to envision and identify unknowns.

Consider, for example, present-day engineering challenges such as self-driving cars or artificial intelligence. These are not fill-in-the-blank or jigsaw-puzzle-style questions. They are questions that are still in the process of being asked in the right way, let alone being solved. How can we transform the complexities of human experience into something machine-readable? How do we take such concepts as “life” and “death,” and transform them into a stable and comparable set of “life events” that can be captured and digitized? Which types of human behaviors can be predicted, or influenced, using algorithms?

Let’s see how we can make the connect-the-dots analogy work for us as researchers. In the opening phases of a new project, the researcher confronts their own kind of connect-the-dots puzzle, but one that behaves differently than either the blue whale or big data examples. Instead of simply taking delivery of a prefabricated, ready-to-solve puzzle, with all the dots present and enumerated, the researcher needs to do the following:

- • Find the dots! Unlike a puzzle with a predetermined answer, your dots are not all laid out on the page for you, conveniently numbered in sequential order. You might find some dots by chance, but most of them you’ll find through purposeful searching.

- • Figure out which dots belong to your picture, and which dots belong to some other picture. Since the dots are not numbered, you need to keep an open mind and be able to envision multiple possible outcomes. An archaeologist who digs in the right place and comes across a deposit of dinosaur bones has the advantage of having all of the bones in one place, but the bones might be mixed with other skeletons, and even if they’re not, an archaeologist still needs to figure out which bones attached to which in order to reconstruct the skeleton. A similar issue faces their colleagues excavating ancient Chinese texts from a tomb. Texts were often written on slips of bamboo, which were then tied into order with string. One tomb might include multiple texts. Over centuries underground, the strings disintegrated, leaving a jumble of bamboo inscriptions. That archaeologist might be lucky enough to have discovered many “dots” in one go, but they still need to distinguish one text from another and then put the bamboo slips in order. Even if you have all of your data points in hand, you still need to know how to analyze them so as to come up with the right solution.

- • Determine which “dots” are not dots at all, but smudges. We call these non-sources. Sources are sources because they have utility for the researcher trying to answer a question or solve a problem. Their usefulness is relative—they may be more useful or less. You may recognize an item as being “someone else’s” source instead of “your” source, because it’s relevant to their Problem. Think of the astronomer trying to discover a new star or galaxy or black hole, who has to filter out the noise of the universe in three dimensions and at great distance. Not everything out there is a source. On the other hand, you might discover that what at first appeared to be a smudge turns out to be something interesting. A single dot could reorient your whole research project.

- • Do all of the above in real time. Not only do the dots not come numbered, and not only do you have to find them, but when you do start finding your dots and making your connections, it is highly unlikely that you will first come across Dot 1, and then Dot 2, and then Dot 3. More likely than not, your first discovery will be Dot 74, followed by Dot 23, and so forth. This places you in the challenging position of having to start interpreting your data without the certainty that you are already in possession of all of it. Visiting another archive, looking at a digital repository, undertaking another day of ethnographic work, another day of an archaeological dig, another day in the chemical compound analysis lab, another oral history interview, or simply another pass at listening to the recording of the interview—these actions add dots to your page. And as more dots appear on your page, the picture becomes clearer. Each additional dot adds a constraint, limiting the number of interpretations that is viable. Where you once had an overwhelming number of possible interpretive lines that could pass through your first few dots, many of those lines disappeared as your data got better. By adding and observing new constraints, you get closer to your answer.

- • Decide when you have enough dots. Obviously, the answer to the conundrum of how many data points is enough—when to stop digging for bones and when to start writing up the report—will vary by research project. It’s during the research process itself that you’ll learn to identify thresholds of probability, confidence, and certainty.

Sources Cannot Defend Themselves

Before you connect some dots (not all of them, yet) on your own project, there are ethical issues regarding the use of sources to consider.

One difference between “grown-up” puzzles and the ones we played as children is that you get to decide how to draw the lines. In the kiddie puzzles, the lines between two consecutive dots are always drawn straight. The games are designed that way. Writing is a different art form, however, and when you construct the narrative of your arguments and your explanations, or when you tell the story of your research findings, you have the choice of connecting your dots using straight or curvy lines—or, most likely, some combination of the two.

Imagine that, in the early phases of our research, we know only five basic facts about a historical person of interest to us:

- • date they were born

- • city where they grew up

- • institution where they pursued their education

- • degree they earned

- • date they died

Let’s consider three very different ways we might connect these dots:

- 1. The ruler-drawn line (tight; no elaboration)

- 2. The curved line (loose; some elaboration)

- 3. The zigzag (extremely loose; highly speculative)

The Ruler-Drawn Line

John Smith was born in 1914, and grew up in Chicago. He received a degree in engineering from the University of Illinois. He died in 1989.

This is akin to using a ruler to draw a straight line between our empirical dots, because it “sticks to the facts” and avoids any and all elaboration. At the same time, it could be said to lack interpretive power. It feels static and even lifeless.

Now consider a slightly looser fit.

The Curved Line

John Smith was born in 1914, on the eve of the Great War in Europe. He grew up in Chicago, then a bustling center of industry. He received a degree in engineering from the prestigious University of Illinois. He passed away in 1989.

Here, the researcher’s narrative has connected, or “passed through” each of the four dots, and yet they have also supplied additional tone and context to the prose. This supplemental context, although empirically defensible (World War I did begin in 1914, and Chicago was a center of industry), still represents a choice, even a strategy, by the writer. Was Smith’s life shaped by the Great War? Was his life shaped by the economic history of Chicago? Why or how much does the prestige of the university matter to Smith’s life? By “pass away,” do they mean he died peacefully? Here the writer is not telling us one way or another in any explicit fashion—they are merely implying. As a reader, we wonder: Are these contexts relevant, and defensible?

Now an extremely loose fit.

The Zigzag

John Smith’s birth coincided with an event of global historical importance—the outbreak of World War I in 1914—and his death, yet another—the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. He received a degree in engineering from the University of Illinois, a choice shaped perhaps by his upbringing in Chicago, then a bustling center of industry headed by Mayor “Big Bill the Builder” Thompson.

In this third example, the writer is clearly taking undue license. Although they have not uttered any factually untrue information—all the dots are accurate, and all of them are connected—a host of dubious cause-and-effect relationships are being implied here, all without a shred of supporting evidence. Was Smith’s Chicago upbringing under Thompson’s mayoralty the “cause” of him studying engineering? Does it really matter that Smith’s birth and death coincided with these events in Europe? (Did the Berlin Wall fall on him?) Isn’t it the case that one might be able to find major events that coincide with the birth and death years of practically anyone?

A few key takeaways here:

- 1. Sources cannot speak for themselves, nor can they defend themselves against you; thus it is your obligation to represent them accurately. As soon as you start dealing with primary sources, you have to make ethical decisions, the first being to represent the sources as honestly as possible.

- 2. Research integrity requires not just dealing in facts but also not forcing them to tell a story. Fidelity to one’s sources is not limited to a question of empirical accuracy. As seen above, even when the author deals entirely in “fact” (the Berlin Wall did come down in 1989), there are, nevertheless, ways to connect the dots that “force” them to say things that the author wants them to say.

- 3. Connecting the dots from sources to arguments is always a deliberate choice involving ethical responsibility. Don’t be lulled into thinking that your responsibilities as a researcher are satisfied so long as your treatment of sources is “straightforward” or “objective.” The “straight-edge” method of connecting the dots is not pure, perfect, or always desirable. A rote inventory of facts can have unwanted effects, such as neglecting essential contexts, or silencing fundamental questions. For a researcher, the connecting of dots always involves active choice. The key here is not to avoid or downplay this responsibility, but to make these choices as deliberately and defensibly as possible. Making decisions is your responsibility as researcher—and at every point, a decision must be made.

As you make choices about sources, be aware: even though sources cannot speak for themselves, this does not mean that sources are merely inert objects subject to the will or manipulation of the researcher. They have a kind of agency of their own, even in their seeming silence.

A source might be any of the following:

- • Incomplete or fragmentary. In our experience, most sources are.

- • Purposefully deceptive—a “pseudo-dot,” to use our earlier terminology. Documents can lie, as can interviewees, objects, and observers.

- • Wrong by accident. People (and the various utterances they leave behind—documents, recordings, etc.) can be unintentionally deceptive, perhaps because they were relying on bad or incomplete information themselves.

- • Biased—sincere or well-meaning in trying to tell truth, but distorted by unconscious bias. Maybe at that time they thought the Sun moved around the Earth. Maybe they categorized peoples or plants differently. Maybe they will tell you, because of who they are, “My culture doesn’t believe in X.” Their claims might be speculative or projecting.

- • Motivated by an acknowledged or unacknowledged agenda. They may be trying to persuade you to adopt a certain point of view, or accept a way of thinking.

- • Inconsistent. A source might be sometimes reliable and sometimes unreliable. Even the experts make mistakes.

These are just a few reasons why the best researchers adopt a critical, searching mindset. They realize that we always have to question our sources, however reliable or authoritative they may seem. We have to seek corroborating or falsifying evidence, since both are valuable. While evaluating your own sources, use the bullet points above as a checklist, and make a note of further steps you might want to take to understand them better.

Just one more caveat to keep in mind while evaluating sources at this early stage in the research process—and this is a crucial one: even if a source you come across is any of the things described above, it can still be useful to you, so don’t reflexively dismiss it. Instead, incorporate it into your question-generation process. Why might this source be trying to deceive me? What phenomenon is this source symptomatic of? There are no “bad” materials when it comes to generating questions or educating your questions. Radioactive material can be used to generate energy. If you come across a suspect source, use it to generate energy for your own purposes.

Taking Stock of Your Research Resources

You have some sources. You’ve started using them to think through your Topic and focus in on your Problem. You’ve been taking both logistical and ethical factors into consideration, tracking your keyword searches and being mindful of how you are connecting the dots with sources. By now, you should be in a mental space where your ideas are taking shape, even as you remain open-minded about where your research might take you. But to turn research ideas into a research project, you need to take into account an array of other material factors, including the following:

- • Time. How much time do you realistically have in which to conduct your research? By when do you have to finish the project? Is it possible to do justice to your questions given this amount of time? What other commitments will be competing for your time between now and then?

- • Funding. How much will it cost for you to carry out the proposed work? What funding is available to you, and what types of research expenses will that funding support? Is it enough? If not, are there ways to relocate your work to make it financially viable, while at the same time preserving your core problem?

- • Writing speed. Are you the kind of writer who works well on tight deadlines, turning research into text rapidly? Or does it take you time to mull over your questions? Does your proposed research depend upon an urgent time frame to be of value?

- • Family responsibilities. How might your relationships affect the time you’ll have for research? What types and volume of research will family obligations allow? Are you a caregiver? Will you be able to subdivide your work into shorter segments, spread out over a longer time? Or does the nature of your research require a long, unbroken period of time to complete?

- • Access. Can you obtain the materials you need to conduct this research? Does your library subscribe to the databases you might need? Will you be able to visit the archives, corporate files, or private papers that you’ve identified as being essential to the project? Is your proposed research politically sensitive, and if so, do you know whether you will be permitted access to sources?

- • Risk tolerance. Researchers in war zones, or on volcanoes, place themselves in life-threatening situations. What is your risk tolerance? How about discomfort? Are you capable of working over long periods of time away from, say, access to medical facilities, electricity, and running water? Be realistic.

- • Abilities. What is your skill set, or that of your research team? What languages do you speak and read? Do you have the necessary expertise to conduct this research?

- • Human subjects. Does your proposed research include work with at-risk populations (such as marginalized communities or children)? Do you need ethics board approval for research involving human subjects? Have you prepared adequately and rigorously to handle the particular challenges of such research, in terms of confidentiality, data security, and more? Can you keep your sources safe, or would your work endanger them?

- • Personality. One of the most abstract, yet also most important, factors to consider is your own personality. While the binary of “extrovert” and “introvert” is a blunt tool with which to categorize sensibilities, ask these key questions: In which kinds of situations do I find my internal battery recharged, and in which situations is it drained? Do frequent social interactions leave me feeling energized, or do I prefer solitary work? With this in mind, what kind of research will my work realistically entail? Will it entail long hours of solitary reading? Or will it involve morning-to-night lab work or fieldwork, where time to myself will be scarce or nonexistent?

The point here is not to be “essentialist” about yourself, your identity, and your capacities. No matter who you think yourself to be right now, remember that research is a powerful process that can and often does challenge and even transform the researcher. So don’t be surprised if it brings out aspects of your character that you didn’t know existed. Likewise, in some cases a project might feel so important to a researcher—their sense of commitment may be so strong—that just this once they are willing to work beyond their comfort zone.

Just remember: it is OK to recognize your own limits and to act in accordance with them. It is equally OK not to pursue a project that would cause you harm.

And above all, know this: even in those cases when you decide not to pursue a project, this is not tantamount to abandoning yourself or your underlying problem. As we have hinted at earlier, and as we explore in more depth later in this chapter, it is possible to find your Problem in another project, and to pursue it just as meaningfully and just as rigorously.

Two Types of Plan B

We hope that everything works out well for you, of course, and that your intended research proceeds smoothly. In case it doesn’t, however, you want to be ready to pursue other possible pathways. As researchers, much of what we do is a plan B of one kind or another. Best to learn early on that being flexible is part of the job description. One of the thrills of research, in fact, is overcoming a challenge or being nimble enough to bypass a roadblock to accomplishing your goal.

Consider these two scenarios.

Scenario 1: Same Problem, Different Case

What do you do when you’ve found the right problem, but the project you envision cannot be done for practical reasons?

A student in Tom’s History of Information class came to office hours to discuss a paper topic. The student was interested in activism and protest and the relationship between social media–based online organization and real-world offline organization. How did the two relate, if at all? Black Lives Matter (BLM) was of particular concern to the student, and so their question as originally formulated was, How have BLM activists used online organization techniques in support of real-world demonstrations and actions?

The topic and question were great, but the methodological obstacles were daunting: if the student had months to interview BLM activists, engage in ethnographic research, and gain trust and access to personal accounts and records of their activities (texts, emails, etc.), this could be a stellar project. But the student had mere weeks to formulate and complete the project, no way to access private collections, nor time to engage in the ethnographic fieldwork necessary to form a credible empirical basis. The student had a great set of questions, but the conditions were just not in place for the project to succeed as envisioned. Not even a seasoned researcher could complete such a project in a few weeks without doing serious injustice to the complexities of the subject matter.

What to do?

Instead of abandoning the problem, the student and Tom carried on the conversation, trying to get at the deeper layers of the question. Instead of getting overly distracted by terms like “social media” and “online organization,” they tried to identify the underlying stakes involved—what each of these terms was a “case of.” Was the student’s interest fundamentally connected to Twitter and Facebook? (No, not necessarily.) Would other kinds of telecommunications and information technologies also be of interest—say, technologies like the telephone, or even the telegraph, if we were to imagine a BLM movement happening in, say, the 1910s or the 1960s? (Yes.)

What about earlier civil rights movements? Did the focus have to be Black Lives Matter or would something from further back in history be valid as well? (Yes, but it would have to be a movement that addressed racial inequalities in particular.)

These exercises enabled the student to identify the underlying “problem” of their questions remarkably quickly.

Suddenly, the researcher had opened up a world of possible cases to consider, all while keeping their core problem constant. How did the Freedom Riders or Martin Luther King Jr. or the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) use communication technologies in the course of their operations? Or, perhaps, how did Gandhi or Cesar Chavez? In particular, how did these organizations use technology, not simply to organize marches well in advance, but in the course of “real-time” emergencies: the arrest of key members, the need to respond to physical emergencies, the need to communicate to news media outlets in the context of constantly changing circumstances—operations that we now take for granted in the internet age?

Suddenly, carrying out this research project no longer depended upon having years and years to do ethnographic research, or gaining access to the private diaries of political activists. Because the student was aware of the problem underlying their work, it was going to be possible to pursue that problem by different means. The chances of finding a relevant body of primary sources became significantly higher, whether in analog format (in the archives at a nearby library, museum, or college) or via online archives.

The key point here is that when you as a researcher know what is core to your research problem, rather than what is merely a “case” of it, this gives you a kind of passport with which you can travel to all kinds of different places, times, and communities—all without leaving behind your research “center.” What is more, even if this student had, right after this conversation with Tom, happened upon a previously unknown repository of primary source materials connected to Black Lives Matter—something that could be explored in time for a final project—this introspective process would still enable the student to approach this case with the insight that only comes with knowing what the core stakes are in the research question. Rather than, for example, assuming that BLM’s techniques of organization are fundamentally unprecedented, all thanks to the existence of social media, the student would be able to situate this “online-offline” dyad within a broader historical context of, say, technologically mediated communication and on-the-ground organization. Either way, the student’s research would enrich their understanding of the problem.

In short, being realistic does not mean abandoning your ideals. Blue-sky thinking can sometimes lead to viable research projects. But if your ambitions outstrip your resources, don’t give up hope. Simply return to the problem that underlies your questions and your project, and seek out another case that might let you pursue it.

Scenario 2: Same Topic, Different Project

What do you do when the project you envision could theoretically be done, just not by you?

As we saw in the Black Lives Matter example, knowing their core Problem enables a researcher to locate it in any number of different cases. You might have thought that you were exclusively concerned with Brazil or women’s literature, but then, by way of discovering your actual Problem, you realized that both “Brazil” and “women’s literature” were in fact cases of that Problem. And this now frees you to relocate your project in different ways.

But there are other limits to the cases you could choose that go beyond questions of the ability of sources or time limits. Choosing the right case for your Problem is also a question of temperament. It needs to fit who you are as a person. Let’s say you want to understand the interior lives of communities who live in the margins of contemporary society: individuals living in homeless encampments in your city, unemployed youth in the Rust Belt, individuals struggling with mental health challenges, or undocumented migrants. As marginalized communities, they may not have the power to shape the narratives the rest of the world uses to understand them—and this disturbs you, emotionally and intellectually.

But let’s also say that you are a deeply introverted person, one who experiences social anxiety. Are you prepared to carry out a project that will likely require you to engage in extensive fieldwork over long stretches of time? Are you able to sustain yourself in contexts where you are perhaps far from your own loved ones, from your own routines, from your support systems for extended periods of time? Are you able to take care of yourself in the context of immersion of this kind?

If the answer is “yes,” then perhaps this is the case for you. If the answer is “maybe not,” don’t feel bad about it. And, even more importantly, don’t try to deny it. You may worry that, if you give up on your case, then you have to give up on your Problem as well—but this isn’t so. As long as you are in tune with your Problem, and truly understand what it is, then it is possible to change your case quite dramatically without abandoning the underlying problem that excites and disturbs you. If you’re not sure how to do that, begin again with more introspective work to help you understand your underlying problem. More insight about your motivations will in turn make finding another compelling and appropriate case much easier.

Now that we’ve examined some of the common ways a project can be thrown off course, as well as how best to pivot, let’s consider some of the more nuts-and-bolts tasks that go into designing a project that works: setting up your workspace, choosing the right tools, and planning a work schedule tuned to your needs.

Setting Up Shop

Research is a craft. And as a craftsperson, it’s important that you set up your shop just the way you like it. If you have friends who are serious artists or musicians, you know how much they love to talk about their instruments, tools, and work habits. Painters search for the perfect brushes, violinists for the perfect bows, oboists for the perfect reeds, and guitarists for the perfect strings. The same is true for chefs and their knives; fishermen and their lures; mechanics and their machines.

You’ll thank yourself if you take the time to think through the design of your work environment. You’ll be spending a lot of time in this physical space and using these tools. Remember how we said in chapter 1 that with questions it’s best to start small? When setting up shop, details matter too. Get a few seemingly minor things right and you’ll reap the gains in increased motivation, productivity, and happiness. There is nothing superficial about giving due attention to physical conditions, since it will affect the well-being of you and your research.

Assess which research tools are worth investing in, given your available resources and what you want to accomplish. Will you be doing a lot of interviewing? You’ll need a microphone, a recorder, and a storage and retrieval system. Will you be composing voice notes in the field? You might want to invest in reliable voice-to-text software, and a long-lasting battery. Concert pianists might shell out more money for a piano than the rest of us would (or could) for a car because for them it’s not a luxury. A well-funded researcher might be able to accomplish more by hiring assistants, but this is not an option for all of us. Consider what you need (wants are secondary), so that you can set up shop in a way that is “perfect for me, here and now.”

When a paring knife or a calligraphy brush sits in one’s hand just right, it makes the act of preparing a meal or composing a work of art incrementally more joyous, inviting, and sometimes seemingly effortless. The same is true for you as a researcher, and so you should give thought to your tools and your workspace.

Here are some of the things you will need for your shop to run smoothly.

The Right Tools

If you write by hand, your choice of pen or pencil matters. Does the graphite in your pencil have the right texture for you? Does it dull or break too often? Do your pen and your writing surface have a nice bite, or does the ink spill out messily (and does that bother you)? How quickly does your hand grow fatigued? Likewise, do you need a $25 leather-bound blank book to get you in the writing mood, or will a $2 cellophane-wrapped sheaf of loose-leaf paper from the local drugstore do the trick? Even this type of decision can have real consequences. The blank book might inspire you to take writing more seriously, and thus to invest more energy in it. Maybe it “slows you down” in a good way, inspiring you to take more time to think through your ideas. A bound book, in contrast, can be intimidating, its price tag and design almost scoffing at you as you lift your pen. This had better be good, you can almost hear it say. You convince yourself that passing thoughts are unworthy of the journal, and try to save its pristine pages for those moments when you truly have something “worthwhile” to say. Every thought must be complete, every sentence sparkling. Drafts and fragmentary thoughts must never besmirch its pages. Your paper choice has led to disaster. Writing and note-taking are hard enough on their own. None of us needs an added inhibition. Perhaps you’d benefit from a less reverent relationship with your writing surface.

These might all seem like inconsequential things, but everything about your workspace will shape your desire to write, the rate at which you will lose steam, and even the quality and tone of your prose. If you use a note-taking system that subconsciously makes you feel rushed and bottled up, like a tiny memo pad, this will affect your work. Your ideas will have less space to unfold, and you’ll constantly be cutting yourself short. By the same token, a note-taking system that feels cumbersome and inconvenient (like an app that requires you to have Wi-Fi access at all times, or a large sketch pad, which is hard to transport) can easily result in writing less often. Like other artists, musicians, and craftspersons, you have every right to be choosy about your tools.

The Right Time of Day

When to write? More specifically, at what time of day should you focus on what type of writing? The answer varies widely from person to person, but here is a rule of thumb: do the “heavy lifting” when you’re fresh and focused, and the more “mindless” work when you’re tired or distracted. If you’re most alert in the morning, or late at night, then that is when you should write new prose. By contrast, many of us experience fatigue or distraction at other times of day. These are good times to pivot and work on those forms of writing that demand less creative engagement: cleaning up footnotes, spell-checking, and the like.

Writing also has its seasons, and sometimes you have to let the project lie fallow to let the soil regenerate. Take a break and go for a walk. Watch a movie. Exercise. Have a meal. Sleep. You may feel like you are taking “time away” from your work—and, indeed, you are. But the truth is, chances are your mind is still at work on the puzzle of writing, and may even untie some complex knots without any conscious effort on your part at all. When this happens (and it happens often!) a writer returns to the page and can sometimes feel as if someone else must have solved the problem or cracked the code for them—because suddenly something that seemed overwhelmingly complex or difficult to articulate simply flows, effortlessly.

You can also ask someone, or something, to read your work to you. When you simply cannot bear the thought of reading through your draft another time, ask a friend to narrate it aloud. Or, if that’s simply too much to ask of even a close friend, use one of the readily available “text-to-audio” functions that translates written text into spoken audio. Sit back, or stand up, and simply listen to your draft, narrated to you in sometimes comically awkward computerized voices. What you will discover is that even when you are unable to detect typos in your draft, having become too familiar with the text to spot them anymore, you will somehow be able to “spot” them immediately when you listen. Something will simply feel “off,” prompting you to return to the text, locate the culprit, and fix the error.

Listen for cadence as well. Is the prose lyrical and patient, or does it feel rushed in parts? Are there any stretches of self-indulgent prose? Are there any points you are belaboring, or perhaps long stretches in need of a segue? Or maybe one paragraph has too many sentences all of the same length, and the passage is crying out for variation.

Remember that when someone does read your work, they don’t just download it instantly into their minds. Reading is an experience, and it’s up to you to make that experience a fulfilling one.

You Have the Beginnings of a Project

Everything is now in place. You’ve checked and clarified your own motivations and interests. You’ve settled on research questions and identified the underlying problem that these questions belong to. You’ve identified the assumptions that brought you here, and you’ve taken ownership of them.

If you still harbor some doubts, take note of them. Write them down. But remember that you are still drafting. Uncertainties are normal. Everything, in fact, is provisional until the study is complete, and a researcher should always remain open-minded and ready to change as facts warrant. If, at this stage, you feel grave misgivings about the direction things are going, you can revisit the exercises you found most useful, and double-check to make sure that you have avoided the commonly made mistakes. But don’t worry. In part 2, you will find even more useful techniques for articulating, evaluating, testing, and rethinking your Problem. You’re not done with introspection.

For now, take another moment to review what you’ve done. By this point, you should have a good sense of what the stakes of this research are for you, and why the results will be meaningful. You’ve also taken some pragmatic steps: doing an initial review of some primary sources, taking stock of your abilities and constraints, seeking advice from your Sounding Board when necessary, and choosing the type of project that best suits your temperament. You’ve even written out a first-draft research proposal, envisioning your project in formal terms. And you’ve been writing all along.

Now it’s time to begin your project.