4

4

Cracking the Code on the Price Increase Conversation

It’s hard enough to get your customer to keep buying the same solution from you. Luckily, you now have a handy, scientifically tested message framework to support your renewal conversations.

But if you’re like the folks in any other organization, you’re not just looking to renew that business. Sooner or later, you’re going to have to ask people to pay more. This is borne out by our own research: In a survey of more than 300 B2B organizations, we found that nearly two-thirds (63 percent) consider price increases “very important” or even “mission critical” for maintaining client profitability and driving overall growth.

That means that in addition to navigating that tricky renewal conversation, you’re also going to have to manage a far more delicate, complex, and politically fraught discussion: the price increase.

It’s a high-stakes conversation that has huge ramifications for your bottom line. In fact, in 2014 Bain & Company noted that pricing has a more profound business impact than gaining market share or reducing costs.* So companies treat pricing with the appropriate reverence, investing in pricing departments staffed with market researchers, analysts, and data scientists busily developing models and algorithms to try to optimize pricing. But analyses and algorithms can only give you the rationale. If you don’t communicate that price change effectively, it will undoubtedly fail in the market.

That’s the lesson from the second part of our survey, which revealed, among other challenges, that companies lack the confidence, messaging structure, and communication strategy needed to effectively communicate price increases to their customers.

A QUESTION OF CONFIDENCE

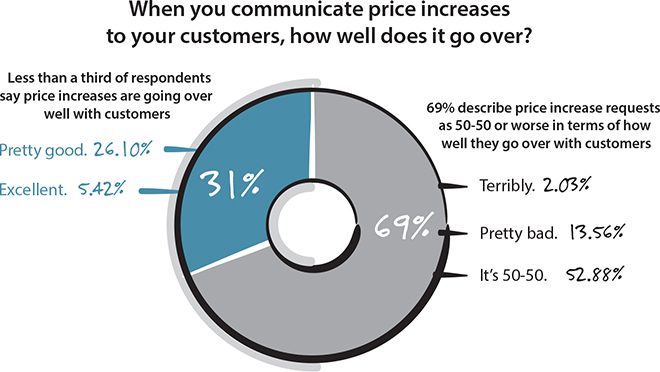

Nearly 69 percent of respondents describe customers’ reception to news of a price increase as “50-50 or worse”—in other words, sometimes it goes over well, other times not so well (Figure 4.1).

It also means that only about a third of companies believe their price increase conversations go the way they want, by either getting an acceptable increase (26 percent) or getting everything they wanted (5 percent). That’s not exactly a glowing endorsement of how the average company is handling this dialogue at an acute commercial moment, and it shows there’s plenty of room for improvement.

Figure 4.1 Price increase communications don’t go over well with customers—most report “50-50 or worse.”

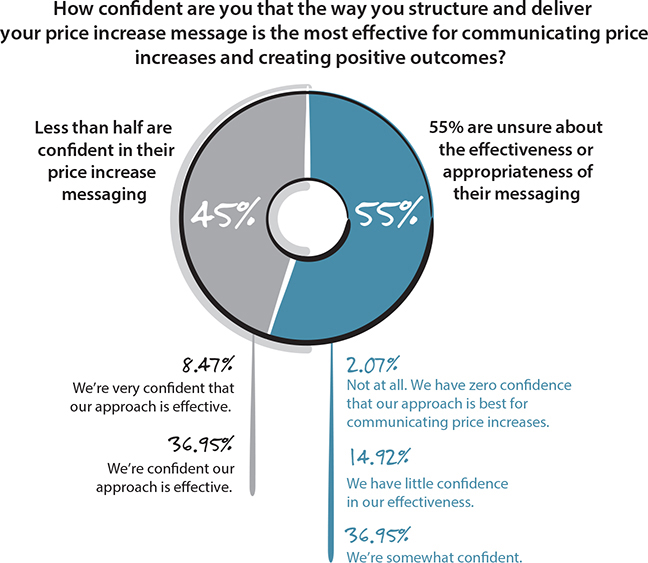

If these important discussions are not going as planned, it’s no wonder survey respondents admitted feeling shaky when asked about their confidence level in the way they’re communicating price increases: Just 37 percent are “confident” in their approach, and only 8 percent feel “very confident.” This leaves the majority—55 percent—feeling unsure about their price increase messaging (Figure 4.2).

So what’s going wrong?

Figure 4.2 Less than half are confident their price increase messages are effective or appropriate.

A STRUCTURAL FLAW

One factor causing many companies to underperform in their price increase conversations could be the lack of messaging structure guiding them. In our survey, fewer than one-third of respondents (32 percent) said they believe their approach to communicating price increases is “highly structured”—meaning they craft a deliberate communication plan using persuasive messaging techniques and support those who own the responsibility with the skills necessary to support those conversations.

Among the other two-thirds of companies struggling with messaging structure, the survey found that:

• 23 percent admit it’s ad hoc , meaning they have no formal approach in place for this conversation and leave it to the responsible parties to develop and deliver the increase message to customers.

• 44 percent say their approach is “somewhat” structured , meaning someone creates a formal communication so the story is consistent but then either leaves the actual delivery up to the responsible parties or sends the customer an e-mail notification with limited direction to the teams responsible for following up.

What’s clear is there’s a definite appetite among B2B practitioners for more rigor around the price increase message. In fact, nearly 80 percent of companies surveyed say they want to make their price increase requests more formal and strategic.

Interestingly, these respondents split into three camps:

1. Those who want more structure but have not made it a priority (40 percent)

2. Those who strongly desire a formalized structure, a message framework, and skills training to improve these communications (21 percent)

3. Those who fall somewhere between these two in terms of their desire for a more formal strategic approach (18 percent)

In other words, there are plenty of people looking for a better way. But there’s no clear consensus around what that better way might be.

COMMUNICATION IS ACCIDENTAL, NOT PURPOSEFUL

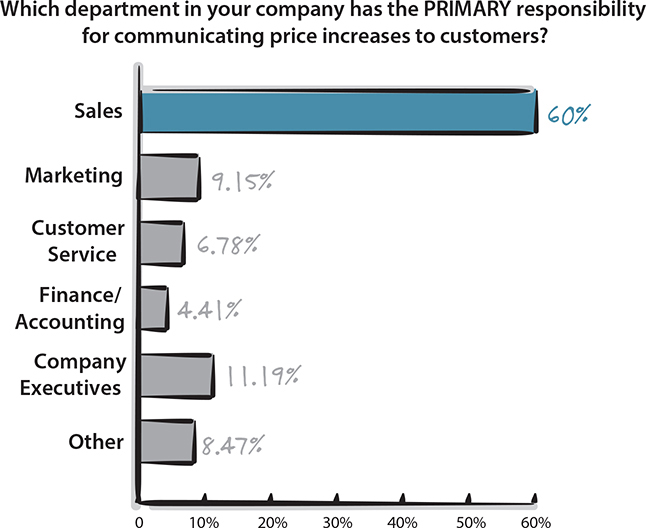

In Chapter 3, you saw that ownership of the renewal message varies wildly from company to company. When it comes to price increases, it appears, at least at first glance, that there’s more clarity: We found that sales is responsible for communicating price increases at 60 percent of the companies we surveyed (Figure 4.3). But if 80 percent of companies believe they need a more formal and strategic approach for messaging price increases, one has to wonder how purposeful that responsibility is. Could the responsibility have simply defaulted to sales because no one else is paying attention to it?

With more organizations building customer success teams, often with direct renewal and price increase targets, ownership becomes even murkier. While the people in customer success might be tasked with the day-to-day customer communications, they often hand off the “tough conversations,” e.g., price increases, to their sales counterparts—preferring instead to focus on activities directly related to customer satisfaction.

But without clear-cut ownership of this conversation, the odds of a poorly communicated, less-than-optimal price increase message increase dramatically.

Figure 4.3 The job of communicating the price increase is usually left to sales—but is that by accident or by design?

WHAT APPROACHES ARE COMPANIES TAKING?

In our survey, we defined the six different messaging approaches our own clients use most frequently in their price increase conversations. We then asked respondents to identify which best describes their own approach.

Ultimately, as indicated in Figure 4.4, no single approach dominates. While it’s clear that companies are trying different tactics, there appears to be a lingering question around what works best. (Spoiler Alert: The two least-used approaches below turned out to be the most effective approaches in our simulation—more on that in Chapter 5.)

Figure 4.4 Since no single approach dominates, it’s likely a substantial proportion are getting the conversation wrong.

Here are the six approaches we asked about in our survey and later tested in our research simulation:

1. Offset price increase by lowering other costs. Introduce new features and benefits to demonstrate how these improvements will lower other costs, thus offsetting some of the price increase.

2. Justify price increase through better results and higher returns. Introduce new features and benefits and explain how these will drive better business results, thus justifying the price increase.

3. Anchor higher price with timed discount. Introduce new features and benefits to justify the price increase, but offer a time-sensitive discount on the higher price.

4. Introduce insight (using provocative Why Change message model). Introduce Unconsidered Needs and show how new capabilities will solve them and deliver better performance, thus justifying the price increase.

5. Secure price increase by reinforcing Status Quo Bias (using Why Stay message model). Document results and revisit the selection process; then present the price increase as one that’s competitive with the industry.

6. Cite external costs as a reason for price increase. Reference external factors (e.g., economy, operational costs, higher supplier prices, increased raw materials costs, etc.) as the reason for the price increase.

All of the above approaches certainly have some grounding in reality—as you see from the distribution of responses. But the wide variance reported indicates that no one knows for sure which approach is most effective, which means a substantial proportion of organizations are most likely getting the conversation wrong. It remains an under-studied, untested component of the customer conversation—and one in dire need of a scientifically tested message framework.

In other words, an area ripe for exploration.

* Stephen Mewborn, Justin Murphy and Glen Williams, Clearing the Roadblocks to Better B2B Pricing, Bain & Company, 2014.