9

9

The Winning Why Forgive Message Framework

Our interest in developing a scientifically proven message framework for apologies kicked off a broader research study with 500 participants across North America and Europe. With assistance from Dr. Nick Lee of Warwick Business School, we created a test scenario in which we asked participants to imagine themselves as a customer experiencing a service failure situation and measured their responses to important SRP-related questions.

The SRP only kicks in when the underlying service failure exceeds what researchers call the “zone of indifference”—meaning a failure that goes beyond the typical day-to-day missteps and token apologies common to most supplier-customer relationships. So we needed to concoct a scenario that ensured participants felt particularly acute pain that affected a wide range of stakeholders.

Here’s what we presented:

Imagine you’re the manager in charge of HR benefits.

Near the end of the benefits sign-up period, the software your employees use to sign up for benefits goes down for an extended period. Employees are e-mailing you directly with questions and frustrations, especially with the deadline looming. They are also submitting requests for support to IT, which cannot rectify the problem because it is an issue with the software supplier itself.

Your HR leadership team and other managers are repeatedly asking you for updates regarding when the problem will be corrected. The software ultimately comes back online, and the sign-up period ends. But this results in a much higher workload for you and your team to ensure all employees have the necessary benefits. You’re also fielding numerous questions and concerns from company leaders worried about the impact this experience will have on employee satisfaction.

Once they read the service failure scenario, here’s what we did next:

1. Asked participants to rank the intensity of their negative feelings toward the supplier in the story on a scale of 1 to 9, where 1 was the most extreme negative perception.

2. Pinpointed the angriest respondents—those who had rated their perceptions 1 or 2—as the subjects for the messaging test.

3. Drafted an apology that included each of the five components (steps) presented in Chapter 8.

Then participants were randomly assigned to one of five apology messaging conditions and were told:

You are about to meet with the software supplier for the first time since this serious incident put your department in such a difficult position. What follows will be the written text of the supplier’s response to the situation.

Finally, the participants read the apology as text and answered a series of questions. The responses from the most angry and frustrated participants (those who initially rated their perception of the supplier the lowest) were used to compare the impact of the various apology approaches. The objective was to determine which message could improve the reactions of the “saltiest” customers and provide a clear, winning formula to follow when you encounter a customer problem.

We drafted a sentence or two for each apology component. We then created multiple test conditions by reordering how the components appeared and were communicated to the customer, each defensible based on how effective any one apology component proved to be in the existing research.

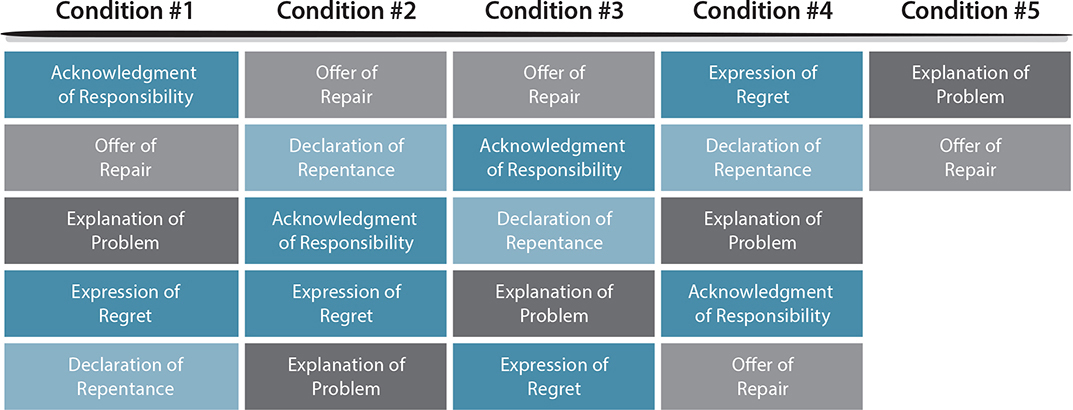

Four different combinations of the five elements were created to test for the best approach. In addition, since a lot of people in B2B environments often eschew what they consider “sugarcoated content” and say they just want the straight facts, we created a fifth test condition as a control. This fifth condition contained only the two most factual apology components and eliminated the more emotional elements. We wanted to see how a factual account of the problem and description of the remedy would compare with the emotionally charged test messages. (See Figure 9.1.)

At first glance, you might not think that such subtle configuration changes, using elements already proved to be individually effective in previous apology science studies, would produce a single, consistent winning framework.

On the contrary, we discovered one of these approaches did outperform all the others across every question asked (remember, we were looking specifically at the responses of the most infuriated customer).

The one clear and consistent winner was test Condition #3 (see Figure 9.2). And despite what people say about not sugarcoating the message, the emotionless, just-the-facts approach consistently landed at or near the bottom on every question.

Figure 9.1 The simulation tested four different combinations of the five apology elements, with a straight, “just-the-facts” condition added as a control.

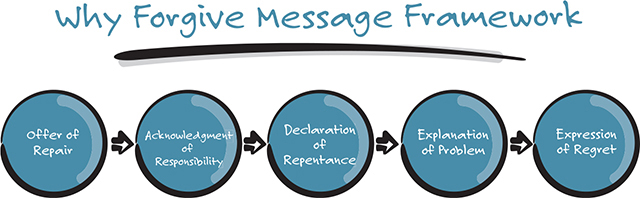

Figure 9.2 Use the Why Forgive framework to increase customer satisfaction and loyalty, even after a service failure.

A CLEAR AND CONSISTENT WINNER

Looking at the questions best related to the Service Recovery Paradox, you will see that this winning approach measurably improves your ability to increase customer satisfaction and loyalty, even after a service failure. We didn’t ask questions about satisfaction or loyalty directly, but instead asked behavioral outcome–type questions related to willingness to continue to buy from or buy more from the supplier. We also asked questions related to advocacy and willingness to recommend or serve as a reference for the supplier. All this was asked after “experiencing” the failure and reading the apology.

Compare this winning framework with what is usually passed on as the conventional wisdom for communicating a service failure in a B2B setting. It’s almost a mirror image. Most people are told to say something like, “Here’s what happened, here’s what we’re doing to fix it, we’re very sorry this happened, it won’t happen again, and here’s what we’ll do to make this right.” But the winning framework looked nothing like this.

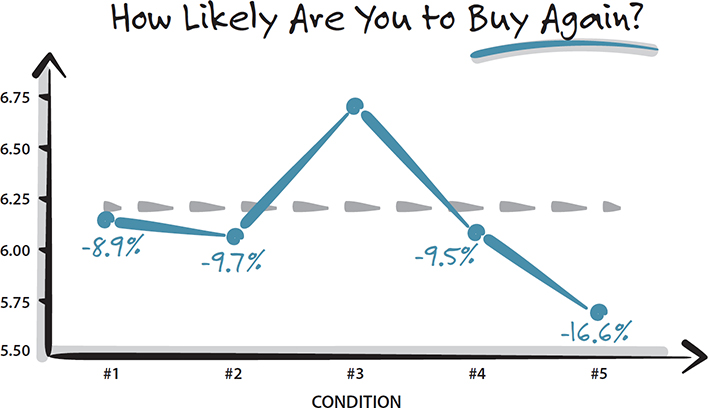

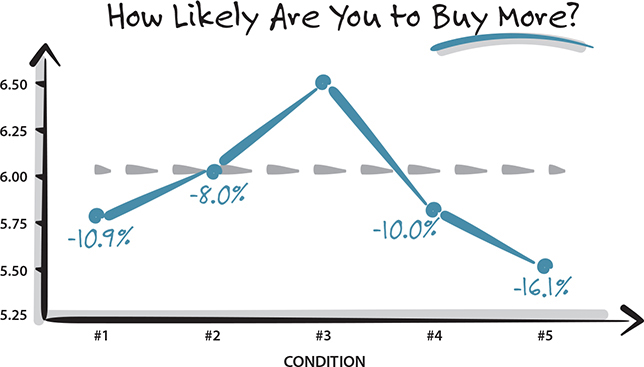

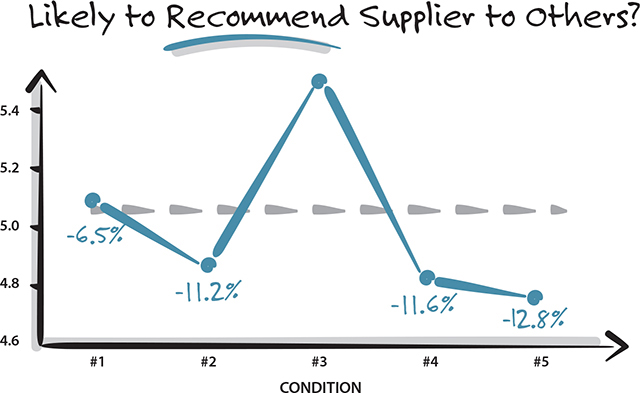

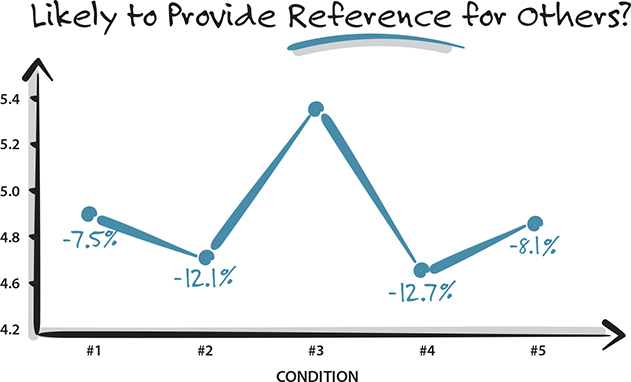

As Figures 9.3–9.6 show, Condition #3 is the clear, consistent winner. Meanwhile, there’s so much variability in the other approaches, you can’t even pick a clear second-place winner. This, despite the fact that the first four conditions all use the exact same content, just presented in a different order. This proves the power of story choreography. It’s not just what you say, but how and when you say it.

Figure 9.3

Figure 9.4

Figure 9.5

Figure 9.6

Figures 9.3– 9.6 The winning apology framework consistently outperformed all other conditions across key questions such as willingness to buy again, likelihood of buying more, and likeliness to recommend and refer supplier to others.

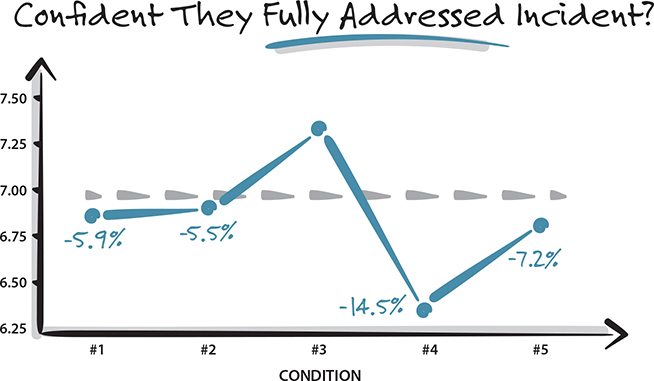

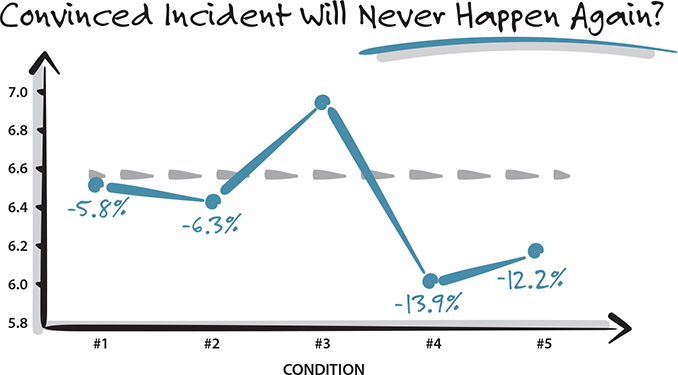

Another key indicator of apology success mentioned earlier is whether your customer believes that you fixed the problem and that the problem will not happen again. Even in this case, you’ll see it’s the same apology message that inspires the greatest confidence in the supplier moving forward—Condition #3. (See Figures 9.7 and 9.8.)

Figure 9.7

Figure 9.8

Figures 9.7–9.8 Using the winning Why Forgive framework increases customer confidence that the problem has been resolved and will not happen again.

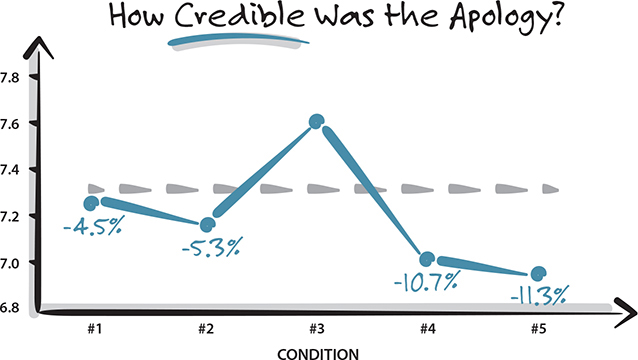

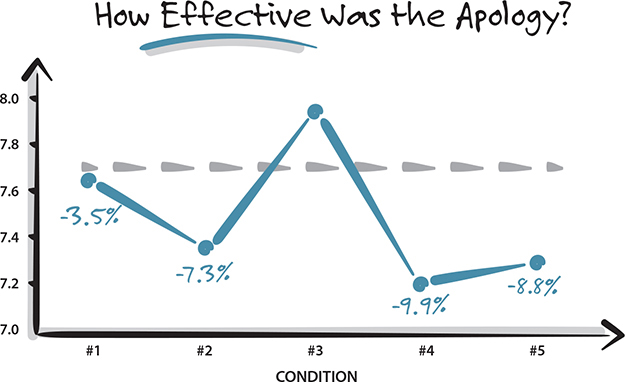

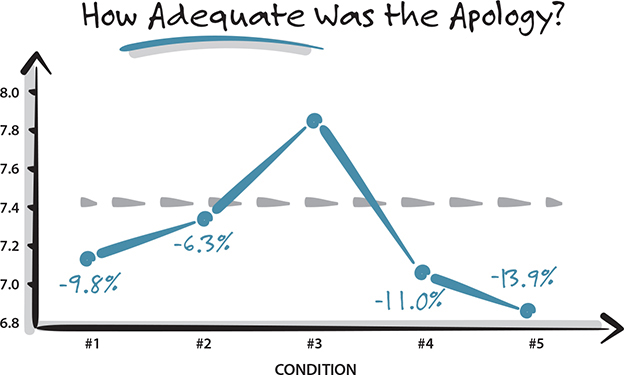

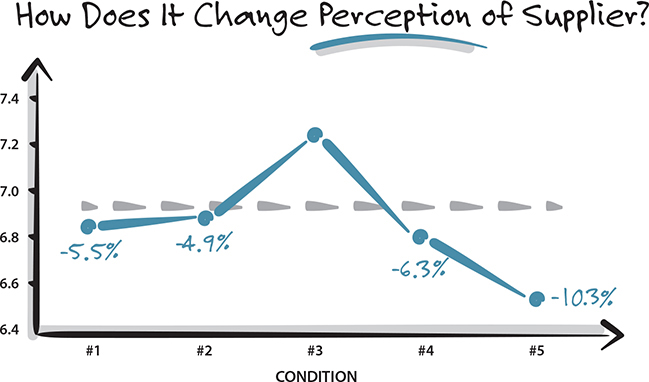

A final set of questions and results was more tied to perceptions of the message itself, considerations such as the credibility and overall effectiveness of the message. Once more, the clear winner is Condition #3. Again—as you can see from Figures 9.9 to 9.12—due to the inconsistent results of the other messaging approaches, there is one clear winner and no clear second choice when it comes to the perceived quality of your apology.

Figure 9.9

Figure 9.10

Figure 9.11

Figure 9.12

Figures 9.9–9.12 Using the winning apology framework boosts the credibility and perception of the supplier, and satisfies customers that the apology was both adequate and effective.

The Winning Example

Here is the winning apology messaging condition as delivered in the test:

1. Offer of Repair. I want to attempt to repair any possible problems this outage caused for you, your team, or your employees. First, I have been approved to provide your company with a one-month refund, twice the length of your benefits sign-up period. It is an expanded refund in recognition that this happened at a peak time for your company. I have also directed our customer service team to manually check all sign-ups that occurred after the software came back online to be sure they were captured accurately. I will let you know the outcome as soon as it is complete, no longer than one week from now.

2. Acknowledgment of Responsibility. The software outage was entirely our fault. It should not have happened at all, let alone during such a critical time for your business. We take full responsibility and are committed to ensuring it will not happen again.

3. Declaration of Repentance. I fully regret that this outage occurred, and our teams are making the necessary changes to make sure it does not happen again. Our outages should be reserved for planned downtime, with advance communication, and we regret that we failed on both accounts in this situation.

4. Explanation of Problem. To let you know what occurred, your software went down after a major power outage at one of our data centers. Your workload was rerouted to our other data centers, as part of our backup plan and service agreement. However, the second center your content was assigned to was down due to preventive maintenance and a hardware update. This caused your system to go down for a period as the system reconfigured to find the next alternative for your workload. We have now updated our redundancy system to avoid anything like this in the future.

5. Expression of Regret. I am exceptionally sorry for this outage, and as soon as I knew about it, I was in constant communication with our technical teams until it was resolved. On behalf of our company, I would like to apologize not only to you, but your leadership team and all affected employees.

THE SCIENCE OF “SORRY”

So why did the winning condition win? What can we conclude from the findings? Decision Science offers some tantalizing theories.

One involves something called the “primacy/recency effect.” This happens when items at the beginning (“primacy”) and items at the end (“recency”) of a list or string of information are more easily recalled than items that appear in the middle.

It makes sense if you put yourself in your customers’ shoes: Tensions are high, and your customers aren’t going to care about the “why” behind your actual apology until they know how you’re going to make things right. So you don’t want to squander their peak attention with a long-winded, self-serving excuse for a failure, because by the time you get around to actually solving their problem, you’ve already lost whatever residual goodwill they might have held onto.

Think of it this way: Imagine you had an experience at a restaurant that was so bad you asked to speak to the manager. Until the manager says she’s going to comp your meal, you don’t want to hear any explanation. In fact, if the manager starts explaining (“It’s unusually busy . . . the server is new . . . they’re short-staffed in the kitchen . . .”), you’ll probably get more frustrated, not less.

Responding to an emotional situation with a rational explanation will backfire. You first need to lower the emotional temperature, and the Offer of Repair is the best way to do that.

But if it were simply a matter of leading with the fix, why did Condition #2 underperform? Remember, both Condition #2 and Condition #3 led with the Offer of Repair—yet it was Condition #3 that was the clear winner. That’s where “recency” comes into play: Research shows that the most resonant part of a message is what the recipient hears last. It’s the sincere Expression of Regret at the end that appears to have tipped the balance in favor of Condition #3.

The lack of an emotional element appears to have also factored into the consistent, miserable failure of the “just-the-facts” approach. If you recall the research on executive emotions outlined in Chapter 1, as well as the cadence of the Why Evolve message framework, you’ll also recall how important the emotional component is to a compelling, persuasive message.

The lesson here? While you might be inclined to shy away from including a sincere emotional component in your apologies, the science shows you’d be making a big mistake. You’d be sacrificing the very component that makes the apology successful.

MAKE YOUR APOLOGIES WORK FOR YOU

Mistakes are inevitable. Lost business doesn’t have to be. The Service Recovery Paradox demonstrates that a service failure could become an opportunity to increase customer satisfaction and loyalty to levels greater than if your customer never experienced a problem with you.

But how you engage your customer to achieve this result matters. In this chapter, you’ve seen there is a clear and consistent apology framework you can use to build and deliver your apology message—and positively influence even your angriest and most bitterly disappointed customers.