♦

A backlash against international migration was already well under way at the beginning of the twentieth century. It was in part a product of increased democratization, and the associated emergence of a new radical populism. Objectors to global integration argued, to some extent correctly, that living standards and labor incomes were being eroded by continuing immigration. After the First World War, however, the discussion became much more intense, and labor standards constituted a central part of analysis of relative economic performance. Currency fluctuations helped to focus attention on international differences in labor costs.

The main way in which the depression is still remembered, at least in industrial countries, is through the demoralizing experience of mass unemployment, with its concomitants of soup kitchens, dole lines, “buddy can you spare a dime?,” hunger marches, and broken families. This experience made unemployment and its avoidance the central political issue of a generation, and led to a call for the protection of national labor. In the United States, industrial unemployment averaged 37.6 percent in 1933. In Germany and the United Kingdom, the peak had been reached a year earlier, with an average of 43.8 percent and 22.1 percent respectively.1 The British prime minister, the Labour politician Ramsay MacDonald, noted at Christmas 1929, at the beginning of the slump: “Unemployment is baffling us. The simple fact is that our population is too great for our trade … I sit in my room in Downing Street alone and in silence. The cup has been put to my lips—& it is empty.” A few months later, in his country residence, he felt no more sanguine. “Is the sun of my country sinking?… We have to adjust ourselves & meanwhile the flood of unemployment flows & rises & baffles everybody. At Chequers one can almost see it & hear its swish in the figures I have been studying.”2

Explaining why an economic shock like the depression and the financial panics of the era produced so much unemployment requires an examination of the dynamics of the labor markets. An important reason why gold-standard monetary shocks had such a profound effect on real output and employment rests on the observation that nominal wages were “sticky” and thus that the monetary contraction led to rises in real wages. If the economic structure had been more flexible, and money wages had fallen in line with prices, there would have been a much smaller impact on output.

Explaining this phenomenon requires a cross-national comparison. The clearest and easiest result from econometric testing is that gold-standard countries were more exposed to the rise in real wages, while devaluation eventually offered a way out of the trap of wage costs. This is part of the argument presented with different tests by Barry Eichengreen and Jeffrey Sachs, by Ben Bernanke and Harold James, and by Bernanke and Kevin Carey.3

But within the national responses there are some differences. One explanation for such variations looks at institutional arrangements. An objection to letting money wages fall along with prices is that there were many prices that were fixed for long periods—especially rents and mortgage payments—and thus a wage cut would impose a sacrifice on workers unless it were accompanied by a general reduction in costs.4 Such a general round of reductions, however, could be accomplished only by massive government interventions in price-setting, and very few countries were prepared to go that far. (An exception is Germany, where the Emergency Decree of 8 December 1931 reduced wages along with interest rates and mortgage payments. It was not a popular measure, and provoked massive protests.)

What are the institutional explanations for different labor market responses? One obvious candidate is the power of organized labor. But some highly unionized countries displayed quite substantial flexibility in wage issues (especially if the gold-standard constraint was lifted). Australia was the most highly unionized country in the world, as measured by the share of workers in unions (45.7 percent in 1929, compared with 33.9 percent in Germany and 33.8 percent in Sweden, and with 9.3 percent in the United States).5 But from 1929 to 1932 the nominal wage fell by 20 percent, and changes in production and unemployment were correspondingly mild: a 9 percent fall in real GDP and a 9 percent rise in unemployment).6 The Australian machinery for centralized wage determination, in which wages were set in response to previous price changes, proved an effective and politically uncontroversial mechanism for reducing wages (although of course real wages remained more or less constant on the basis of such a formula).7 On the other hand, the United States, with a very low rate of unionization, had a very dramatic rise in unemployment. It is clear that union presence or power on its own is a poor explanation of depression-era unemployment.

A second institutional factor is the way in which lessons of previous economic events had been received. In the United States, wages responded much less quickly to demand shocks in 1929–1933 than they had in the short but very severe postwar depression of 1920–21. The widely learned lesson of the early 1920s was that wages had fallen too rapidly, and had thereby intensified the depression. President Hoover in the Great Depression tried to persuade companies not to cut wages in response to falling demand, since he believed it was above all necessary to maintain consumer purchasing power. At least some large employers (General Motors and International Harvester) appear to have followed his advice.8

A third answer might lie in institutional arrangements that strengthened or hardened the position of labor negotiators. In both the British and German case, fiercely fought historiographical debates have focused on this issue. In Britain, an argument was made during the depression era that the high level of unemployment benefits (the “dole”) and the availability of benefits to the short-term unemployed increased the long-term rate of unemployment. At its lowest in the interwar period, unemployment was as high as in any year before the First World War. In his contemporary book on the depression, Lionel Robbins claimed: “The cartelisation of industry, the growth of the strength of trade unions, the multiplication of State controls, have created an economic structure which, whatever its ethical or aesthetic superiority, is certainly much less capable of rapid adaptation to change than was the older more competitive system. This puts it very mildly … The post-war rigidity of wages is a by-product of Unemployment Insurance.”9 This view was set out more systematically at that time by Edwin Cannan and by Jacques Rueff.10 At the end of the 1970s it was revived—to great controversy—by David Benjamin and Levis A. Kochin, who focused their account of the impact of the insurance acts of 1911 and 1920 on the search process: the existence of benefits allowed workers to continue searching for better-paid jobs for a longer time, and thus drove up the general wage level. They tried to demonstrate how inflexible the British economy had become, so that in the depression era nominal wages fell by only 3 percent and unemployment increased by 22 percent (a quite dramatic contrast with the Australian experience).11 The subsequent debate substantially modified the initial argument, which had been insufficiently attentive to the microeconomics of the labor market. Heads of household suffering unemployment were less likely to be satisfied by benefits (which were substantially lower than their previous wages), but the search argument applies better for dependent family members.12 An explanation for the strikingly lower rates of youth unemployment in interwar Britain may also depend on wage structures, which paid much lower rates to workers under eighteen and twenty-one, so that many young people were laid off when they reached an adult age.13

For the German case also, an argument that had been frequent in the interwar period was revived in the late 1970s, by Knut Borchardt. Wage increases, which were not matched by comparable productivity gains, turned Weimar into a “sick economy.” Nominal hourly wages, as set by wage agreements, were 33 percent higher in 1929 than they had been in 1925, and actual earnings were 37 percent higher. These were equivalent to real increases of 22 and 26 percent respectively.14

The major cause of the German wage push was a combination of trade-union power with a state arbitration system, in which binding settlements could be imposed on the participants in a labor dispute. Since a tendency in such arbitration is to split differences, workers could generally reckon with increases. Some contemporaries insisted on the ability of the political process to influence wage negotiations. In particular, the socialist politician and economist Rudolf Hilferding coined the idea of a “political wage.” In the historiographical controversy that followed Borchardt’s article, Theo Balderston and Johannes Bähr tried to show that the arbitration system merely reproduced the logic of the labor market (which might be read out of the actually paid wages, as compared with those fixed in agreements).15 Since the supply of labor was fixed, Balderston argues, the rise in wages reflected the strength of demand, especially for German exports, in the boom years of the late 1920s.

This argument—and indeed the similar debate in Britain—of course depends on the assumption that the labor market is of a fixed size. It is striking that in none of the literature critical of the Borchardt thesis is there any reference to the restriction of the labor market by migration controls. Yet this was a major feature, one that distinguished the interwar economy from that of the more fully globalized prewar period. This in short was yet another policy area where a major and destructive reaction against globalization set in and distorted the economic structure.

During and after the First World War, immigration was generally much more restricted; the model for such restriction was provided by the United States. In 1917 the Immigration Act excluded a wide class of aliens as undesirable: idiots, the feeble-minded, epileptics, those of “constitutional psychopathic inferiority,” drunkards, paupers, beggars, sufferers from tuberculosis or other “loathsome diseases,” polygamists, anarchists, prostitutes, laborers under contract or those whose passage had been paid for, and Asians (with a geographic definition of origin). Those excluded by earlier acts (Chinese and Japanese) were again excluded. A parallel Act, the Burnett Act, also imposed a literacy test.

The American discussion of the 1920s drew on the resentments that had already been expressed before the First World War, and directed against the so-called “New Immigrants,” who were—the stereotype went—economically motivated (rather than politically or ideologically, as the older immigrants had—largely erroneously—labeled themselves). The two Restriction Acts of 1921 and 1924 aimed at altering the ethnic and national mix of immigrants and at greatly restricting the overall flow. The 1921 act reduced the annual number of immigrants from over a million to a maximum of 357,803 and stipulated that the maximum number of immigrants of any nationality should be 3 percent of the foreign born of that nationality resident in the United States in 1910. But the 1921 act did not restrict land immigration, via Canada and Mexico; this loophole was remedied by the 1924 act. That act took the crucial base year back to 1890, in other words before the large Mediterranean and Russian and east European emigration of the 1890s and 1900s. The quota was now set at 2 percent of the foreign-born individuals of that nationality in the continental United States as measured in the census of 1890.

Obviously this legislation was not completely and immediately effective. Smuggled immigrants amounted to an annual 50,000–100,000. There were some striking instances of large-scale avoidance. In 1924, for instance, the French colonial authorities in Tunis expelled some 10,000 Italians as part of a clampdown on criminality, and the U.S. secretary for labor reported that they were “welcomed with open arms by the United States.”16

What economic effects followed from the new policies of restriction? In the nineteenth century, construction activity had been linked to waves of immigration. For the 1920s, on the other hand, construction was the weakest point in an otherwise booming economy. From 1926 through 1929, at the height of 1920s prosperity, spending on construction fell by $2 billion, and the sector remained very weak during the depression and the recovery of the 1930s. Another measurement of the feeble character of building is given by the lumber industry: by 1929 output was only 91 percent of the 1925 peak level.17 Nevertheless, despite the obvious precedent of the nineteenth-century experience, traditionally historians have been unwilling to see reduced construction in the 1920s as an outcome of immigration policies. One calculation, for instance, suggests that a laxer immigration regime would have raised housing investment by less than one percent.18 This is too restrictive an estimate. But such estimates should not lead us to minimize the extent of the impact of immigration on economic growth, for they systematically exclude any consideration of the effect of immigration on labor market behavior.

The primary motive for the change in the U.S. stance reflected the impact on the labor market of large numbers of poor and unskilled immigrants. The first congressional votes on a literacy test, which was approved by both the House of Representatives and the Senate but was vetoed by President Grover Cleveland, came in 1897. In 1915 both House and Senate again voted for such a measure, by larger margins, and Woodrow Wilson vetoed the bill. In 1917 anti-immigration votes were sufficiently numerous to override the presidential veto. The pressure to stop immigration had little to do with the war. It was a result of the surge of immigration in 1900–1910, which had a discernible impact on the wages of less skilled workers. Economic circumstances and voting patterns in Congress were linked. Whereas in the large East Coast cities, with large immigrant communities, there were pro-immigration majorities, elsewhere workers moved to an anti-immigrant position. They directed their hostility precisely against the less qualified immigrants, who posed the greatest competitive threat, those from eastern and southern Europe.19 As a consequence, it is possible to see the development of anti-immigration sentiment as motivated solely by a quite rational perception of the dynamics of the labor market, without any additional racist argumentation.

But there was also a distinctly “racial” cast of argument. At the 1927 Geneva world population conference, an American, C. B. Davenport, explained the U.S. goal of “the preservation of a reasonable degree of homogeneity in the population of the United States. Possibly,” he continued, “the lesson learnt in the great war in Europe, of the strong differences in feeling between different nationalities in Europe, led us to dread lest there should come about that which seemed imminent, namely, that we should have represented in the United States groups which should make it a little Europe, with warring nationalities included.”20

The other classic countries of immigration soon adopted similar discriminatory measures. Canada listed “preferred” countries (Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland) whose citizens were admitted on the same terms as those of Britain; and then “non-preferred” European countries, whose peoples could come only as agricultural laborers or domestic servants.21 South Africa after 1930 virtually halted immigration from “non-preferred” countries altogether. Australia, at the instigation of its powerful labor unions, negotiated limits on the passports issued to immigrants from east European countries and Italy.

Migration was clearly an international issue, and restrictions reduced potential living standards in the countries of emigration. But attempts to deal with the regulatory issues on an international level largely failed.

The discussion of international measures to deal with fears and accusations of unfair competition and wage pressure exerted across national frontiers began in the nineteenth century. Sometimes the memorandum presented by the enlightened New Lanark factory owner Robert Owen to the international Congress of the Concert of Europe at Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle) is considered to be the beginning of international labor legislation. Owen wanted the principles of enlightened industrialism to be extended from Britain throughout the world. Instead of competing with other countries, Britain should “extend the knowledge which she has acquired of creating wealth or new productive power, to the rest of Europe, to Asia, Africa and America.”22 Owen invited the congress statesmen to see the progressivism of New Lanark as a model for widespread international emulation. The proposition is an obvious one: good reforms by one state could be undermined by unenlightened policy in other countries. Low-cost competition would make the improvement of living conditions impossibly expensive and bankrupt enterprises that wished to be humane. During a discussion of child labor legislation in France in 1838–39, the economist Jérome Blanqui suggested an international treaty “adopted simultaneously by all industrial countries which compete in the foreign market.”23 Louis René Villermé, a surgeon employed as an inspector of textile factories, suggested a “holy alliance” of manufacturers, “not only in his vicinity, but in all countries where his goods are sold … to bring to an end the evil with which we are afflicted instead of exploiting it to their profit.”24

The first really systematic move occurred in 1889, when the Swiss government issued invitations to a preparatory conference on international labor legislation. As a federal country with intensive cantonal legislation, Switzerland was a natural laboratory for such initiatives: one canton would not be well advised to pass a particular piece of labor legislation unless the same agreement was reached in the others. At the initiative of the new German emperor, Wilhelm II, the conference was eventually held in Berlin, not Switzerland, and in the event produced no concrete outcome. The next Swiss initiative was much more successful: in 1905 and 1906 conferences in Bern produced an agreement for the prohibition of night labor by women, as well as a ban on the use of white phosphorus in matches. At the time of the meetings, Austria, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, and Switzerland already had a ban on night working. The major aim of the discussions was to bring “backward” states, notably Japan, into an international system, and thus prevent cheap and exploitative labor practices posing an unfair economic threat.

The next development was a response to a dramatic failure of international working-class solidarity. Many socialist and labor leaders had seen in concerted action, across national boundaries, a chance of improving labor standards, but also of preventing war. In August 1914, however, there was little protest, and most of the European working class seemed to be swept up in the fervor of war enthusiasm. As the war went on, however, every belligerent country bought labor peace and increased munitions output by a promise of a better postwar world. The German economic planner Walther Rathenau explained that “the trenches cannot be paid for with a deterioration of the standard of living.”25 This sentiment was generally shared. Very soon after the outbreak of the European war, the American Federation of Labor passed a resolution calling for a meeting of labor representatives as part of a future peace conference, “to the end that suggestions may be made and such action taken as shall be helpful in restoring fraternal relations, protecting the interests of the toilers and thereby assisting in laying the foundations for a more lasting peace.”26

The second plenary session of the Paris peace conference on 25 January 1919 passed a resolution appointing a commission “to inquire into the conditions of employment from the international aspect, and to consider the international means necessary to secure common action on a permanent agency to continue such inquiry in cooperation with and under the direction of the League of Nations.” The major drafting initiatives came from the British, but this was also one area of the conference’s activities that attracted some German support. After the military breakdown, and in the context of a rapid democratization and an extension of rights to labor representatives, the German Labor Office saw in international labor action one of the most attractive aspects of the whole peace process. In February 1919 the German government submitted a draft program for labor provisions in the peace treaty, which included an expression of the right of every worker to work and reside where he could find employment, and called for a ban on prohibitions of emigration and immigration. Immigrant workers should have the same conditions and wages as local workers.27 The French proposals also made a great deal of the freedom of migration.

Labor issues were placed in Part XIII of the Versailles Treaty, which established an International Labour Organization (ILO), with a permanent International Labour Office. Its Governing Body of twenty-four would have twelve representatives of governments, six of employers, and six of workers (in 1922 it was enlarged to thirty-two, after a struggle about the representation of non-European states). The ILO had a sanctions mechanism for enforcing conventions, analogous to the general practice of the League. A member could submit a complaint that another member was not in effective observance of a convention. The Governing Body had the power to appoint a commission of inquiry, whose report would be published by the League; within a month of the report, the parties to a dispute were obliged to accept the report or to refer the matter to the Permanent Court of International Justice, which could impose economic sanctions on “defaulting governments.”

Trying to provide international guidelines for working conditions offered one path to a solution of labor problems in the context of a global economy. Another approach—a more ambitious project even than attempting to coordinate labor legislation—lay in the control of population movements. In Paris, some delegates—in particular from countries of emigration such as France, Italy, Japan, and Poland—wanted to bring the ILO into controlling and regulating migration. But such proposals raised objections from the countries of immigration, in particular the United States, which thought that immigration should be subject to a consideration of national interest. Subsequently Italian delegates at the annual conferences frequently raised the issue of a world redistribution of the factors of production, in which countries with surplus agricultural land should accept the workers of countries with no unoccupied land.28 In 1921 the League of Nations and the ILO held an international congress on migration in Geneva, but its deliberations were crippled by the refusal of Australia and Argentina (large recipients of immigration) to send delegations. The Brazilian delegation announced that control measures were urgently needed to “discipline migration in the higher interests of mankind.”29

With such failure, the ILO inevitably restricted itself to the field of labor conditions. The first international labor conference, in Washington in 1919, discussed the extension of the 1906 Bern Conventions, the protection of female labor, and the application of the eight-hour day or forty-eight-hour week. There was a substantial Asian presence at the conference, with delegations from China, India, Japan, Persia, and Siam. In 1919 in Paris, the Japanese delegate had explained

that the Government and people in Japan were much concerned with labour questions, but their conditions were very different from those of Western Nations, and therefore there might be certain measures of reform embodied in proposed conventions which were necessary for a large number of other countries, but which, if adopted immediately and unconditionally, would be contrary not only to the interests of industry, but also to those of the workers themselves in Japan. Consequently, in accepting and carrying out such proposed reforms … Japan should have the opportunity of subjecting their execution to a period of delay or of introducing some exceptions or modifications.30

In the 1920s the Japanese textile industry raised the issue of inequality of labor conditions as a factor in competition. But increasingly the Labour Office recognized that if it were to take the competition issue as a basis for its activity and the enactment of new conventions, it would be doomed to failure. In 1927 the director’s report argued that “Possibly, in the last resort, the whole system of international conventions which sprang from the traditions and precedents of the pre-war period correspond to conditions of international competition which no longer exist today in precisely the same form.”31

By the beginning of the 1930s the Hours of Work convention had been ratified by 18 countries, the Unemployment Convention (on reciprocity in unemployment insurance) by 24, the Convention on the Employment of Women before and after Childbirth by 13, the Women’s Night Work Convention by 27, the Minimum Age (Industry) Convention by 23, and the Night Work (Young Persons) Convention by 27 countries. From 1919 to 1934, 44 conventions and 44 recommendations were adopted; but most were adopted at the first three conferences, and the ILO principles proved increasingly difficult to translate into practice. General conventions, say on hours of work, which were always treated with caution and skepticism, and required repeated reaffirmation at the international institutional level (in 1930, a new convention on the eight-hour day and forty-eight-hour week was instituted), were generally less significant than rather concrete measures, with regard to issues such as industrial hygiene.

In the course of the world depression, as unemployment mounted, the issue of hours of work became increasingly controversial. At the beginning of 1932 the Governing Body of the ILO urged the extension of the Washington Hours of Work Convention. The eight-hour day could be a foundation for the abolition of overtime and the reduction of working hours before workers would be dismissed in response to bad business conditions.

In 1932 the report of the ILO director urged the redistribution of work and the increasing use of short time, as well as the maintenance of wages and the regulation of migration through international agreements. Such initiatives had an increasingly unreal air. While some governments, notably the Hoover administration in the United States, tried to keep wages up, in order not to reduce purchasing power further, in most countries the pressure went the other way. In the light of a diagnosis of the crisis that emphasized the difficulties posed by falling investment levels, the Genevan cures involving wage maintenance did not look attractive.

Professor Alfred O’Rahilly of the Irish Free state provided a neat epitaph on the initial work of the ILO in 1932:

Now the factors governing the world today are entirely beyond the control or competence of this Organization. The fact is deplorable, but undeniable. This Organization was designed for a world which has practically ceased to exist; a world of comparatively stable prices and profits, of industrial expansion and colonial exploitation; a world of big powers and submerged nationalities. Today we are living in a world of fluctuating prices and collapsing profits, an era of industrial contraction and resurgent nationalism, when production has outrun consumption and the machine is ousting man, and usury—miscalled finance—has whole nations in its grip. And in spite of the creation of these two great international organizations, the League and ourselves, the world today has economically disintegrated, ever since the war, into fragments and powder—men, money, goods, petrified as if by the trick of a cinema photographer.32

As transoceanic migration became harder because of increased restrictions, initially intracontinental migration surged. In the 1920s many Italians who might otherwise have gone across the Atlantic went to work in northern and western Europe. Both oceanic and continental migration was shorter term now, in that there was more return migration. Forty-one percent of Italian emigration was “continental” in 1920; by 1938 the share was 80 percent. But even such migration fell off abruptly in the depression, when the new (continental) countries of immigration launched their own restrictions. In 1932, at the height of the world depression, 16,000 people were turned back at the Swiss frontier on the grounds that they had insufficient funds to support themselves.33

The European country with the highest levels of immigration was France, where the movement was more politically acceptable than elsewhere. It could provide a remedy to the French demographic weakness, which had put the country at a disadvantage in its historic rivalry with Germany. In addition, immigration compensated in some manner for the great losses of the war. In 1911 aliens had constituted 2.86 percent of the population; by 1921 the share had risen to 3.78 percent. With more reconstruction it went higher, to 6.15 percent in 1926, and to 6.91 percent in 1931. Unlike other countries, France made immigration easier. Already in 1889, there had been automatic naturalization for children born in France to alien parents who had also been born in France, and optional naturalization for other children born in France. In 1927 naturalization was made possible for aliens who had been in France for at least three years.

The largest single national share of the immigrants to France was Italian (in 1926 Italians constituted 31.7 percent of aliens; 15.7 percent came from Russia and Poland, and 13.5 percent from Spain). National groups were recruited for particular activities. The Mine Owners Committee sent recruiting missions to Poland, and in 1919 a Franco-Polish emigration treaty regulated the process of migration. By 1923, for coal mining in the department of Pas de Calais, 39 percent of all underground workers and 53 percent of hewers were Polish. While Poles tended to work in mining, Italians worked in construction and agriculture. With such high proportions of foreign workers, foreign countries—rather than French workers—began to complain about unfair competition. One British survey of population developments at this time, for instance, referred to the “complaint heard in foreign countries that France was building up a new form of slave state.”34

Germany followed much more restrictive policies in the 1920s, both in comparison with prewar practices and in comparison with those of its western neighbor. In the first decade of the twentieth century almost 600,000 Italians came to Germany.35 Almost all were repatriated quickly after the outbreak of war in 1914. There were Poles, especially in eastern agricultural work and in the coal mines of the Ruhr valley. Before the war, some attempt had been made to restrict movement and to provide for central registration. The employers’ associations took on this task in 1907. The postwar Weimar Republic moved quickly to the establishment of a major series of welfare reforms, and trade unions were powerfully represented in government and decisionmaking. It was much more of a workers’ state. Correspondingly, inward movement, which might have upset the precarious political equilibrium, was discouraged. The Employment Exchange Act of 22 July 1922, which set out to guarantee the rights of German workers to welfare benefits, regulated foreign recruiting. Foreign labor was to be employed only if there was an actual shortage of German labor. A treaty between Poland and Germany in 1927 restricted migration to agricultural workers and permitted only temporary and seasonal movements. Each worker needed a contract with a specified employer before he was permitted to set out. In return, limited rights to sickness and accident insurance were provided.

Did the different migration experiences of France and Germany change the dynamics of the labor market? Most analyses of the problems of the Weimar economy, while emphasizing the problems caused by high wage settlements in the later 1920s, in the circumstances of a stable, gold-exchange standard currency, have not attributed a great role to the absence of substantial inflows of foreign workers.

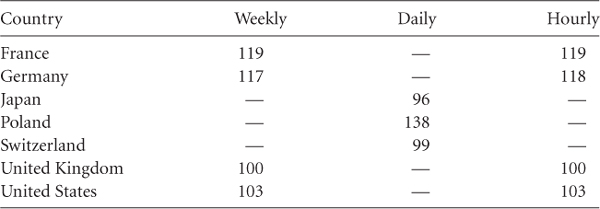

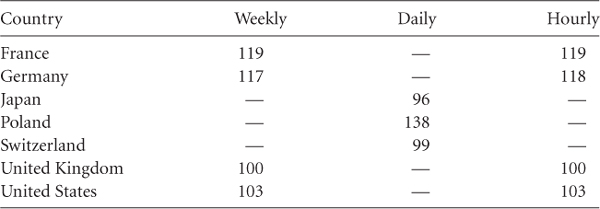

Source: Calculated from International Labour Review 26 (1932): 248–254.

Table 4.1 shows that the behavior of French and German wages showed little difference, but that the major distinctions lay between countries with and without inflationary experiences in the first part of the decade. Japan, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States all had more or less stable wages, while the continental European countries, where inflationary expectations had been built into wage bargaining, continued to experience quite substantial wage increases during the stabilization period.36 The political drama of a return to the gold standard apparently did nothing to change the actual behavior of unions and industrial bargainers.

When the labor market turned more difficult, many of the foreign workers in the host countries left by themselves. In 1927 and 1931, departures from France exceeded arrivals.

Particularly populist politicians of the right—but also labor organizations and the parties close to them—saw immigration as a threat to living standards and welfare rights. The French socialist statesman and director of the International Labour Office, Albert Thomas, told the 1927 World Population Conference, held in Geneva, that a “rational migration” policy was needed to deal with the demographic problem, since “of all demographic phenomena, migration is the most susceptible to direct intervention and control.” Thomas compared the policies of the United States and France to protection by customs tariffs. In his peroration, in which he raised the possibility of an international supreme migration tribune, Thomas said: “An attempt should be made to tackle the migration problem, and this attempt should be made internationally. The question is one of peace or war. If no action is taken, fresh wars, perhaps even more terrible than those which the world has recently experienced, will break out at no distant date.”37

Countries that had previously sent large numbers of emigrants now found that aggressive imperialism might be an alternative. Both Italy and Japan had experienced high rates of emigration. Both now tried first to organize their emigrant groups. In 1927 Foreign Minister Dino Grandi started an official campaign against emigration. Italian subjects were allowed to leave with the intention of settling abroad only if they were moving to be with a near relative or had a contract of employment (which immigration restrictions in host countries made it increasingly difficult to obtain). The restrictions were briefly relaxed in 1930 as the depression affected Italian labor markets and outward migration shot up (88,054 in 1929, but 220,985 in 1930 and 125,079 in 1931). At the same time as obstacles were placed on outward migration, Mussolini announced a new campaign to increase natality (which was unsuccessful: the number of births per 1,000, which had fallen from around 30 in the early 1920s to 27.5 in 1927, continued a remorseless decline, to 25.6 in 1929 and to 23.4 by 1934).38

Russia, which adopted radical policies in every other regard, also tried almost completely to prevent emigration. This stance was defended in terms of ideology. “The socialist state,” its representatives announced, “considers people as its most valuable asset.”39

There was a corollary to the increasingly popular principle that movements across national frontiers should be prevented. If there were intolerable pressures within the national frontiers—which had previously been dealt with by the export of goods or of people—they could be answered in the new environment in which goods and people could not move only by shifting the frontiers themselves. Is it a coincidence that the countries that turned dramatically and destructively to military expansion in the 1930s were countries that had previously been large suppliers of emigrants?

Japan rationalized the push into Manchuria after 1931 in terms of the need to find room for settlement in a world in which Japanese export industries could no longer find markets. It would be a “lifeline” for the supply of raw materials, the extension of a new market for Japanese goods, and a means of relieving Japan’s rural overpopulation. Japanese business described the schemes for the state-led economic development of Manchukuo, the Japanese puppet state, as a “solution to the current deadlock,” and an “escape from depression.” The development occurred along Soviet central planning lines, with mostly public-sector investment—but the large industrial trusts, the zaibatsu, bought the bonds floated by the state of Manchukuo.40

Mussolini justified the invasion of Abyssinia, which meant the definitive break of Italy with the League of Nations system, as a recreation of the Roman empire, but also as a search for an outlet in Africa for the surplus Italians. Previously they had moved across the Atlantic and weakened the fabric of Italy. Now Italians would build the new empire around the Mediterranean (“our sea”). In 1932 the Italian foreign minister, Dino Grandi, had explained to the Senate that a nation of 42 million could not be “confined and held captive within a closed sea.” Libya would be the initial destination. The colonial undersecretary explained state-led colonization as a necessary reaction to the depression, with decisive methods needed to “speed the completion of the truly grandiose undertaking that is purposed.” Africa would be the new destination for Italian emigration and national self-assertion. “Africa, with its huge territories, its unexplored mineral and agricultural wealth, its possibilities—in vast zones—for European colonization, its growing capacity as a market, truly constitutes a necessary complement, the supreme resource of our old continent, which is demographically too dense and economically too exploited.”41

In Germany the nationalist literature opposed to the Versailles settlement had complained in the 1920s that the German people were cramped by the country’s territorial losses. One of the most influential novels of the 1920s was Hans Grimm’s Volk ohne Raum (People without Space), published in 1926, of which almost 600,000 copies were printed by 1939. The title made the point clearly: Germany no longer had sufficient space. But the author believed that “the German needed room and sun and inner freedom in order to become good and beautiful.”42

Hitler took up the popular theme of the need for an outlet for population. In his programmatic account of his political beliefs, Mein Kampf, he explained that “The right to possess soil can become a duty if without extension of its soil a great nation seems doomed to destruction.”43 He contrasted the German experience with that of the United States, with a boundless frontier, or of the west European colonial countries, Belgium, Britain, France, the Netherlands. In his unpublished foreign policy statement, subsequently known as Hitler’s Secret Book, he maintained: “Regardless of how Italy, or let’s say Germany, carry out the internal colonization of their soil, regardless of how they increase the productivity of their soil further through scientific and methodical activity, there always remains the disproportion of their population to the soil as measured against the relation of the population of the American union to the soil of the Union.”44 The United States had been so productive, not just because of its natural riches and the vast extent of its territory, but because it attracted the most valuable immigrants from Europe. Emigration had correspondingly deprived Germany of the most courageous and resistant Germans.

Immediately after his appointment in January 1933 as chancellor of Germany, Hitler explained the basis of his future policy to a private meeting of army leaders. There were in his view two alternative solutions to the German problem. A first option was that Germany could develop industrial potential by reviving the export economy after the ravages of the depression. But at the beginning of the speech, he had emphasized the limited capacity of the world market to absorb exports. So the second alternative was “perhaps—and probably better—conquest of new living space in the east and its ruthless Germanicization.”45

The theory of Lebensraum depended on what appeared to be a rational economic analysis—rational, that is, in the context of the depression and depression economics. In the past, countries had expanded their population on the basis of an inadequate agricultural production by selling industrial manufactures in exchange for food imports. As every country adopted its own industrialization strategy, and as world trade in manufactured goods diminished, it would become ever harder to sustain imports on this basis. Germany’s economic difficulties would thus grow from year to year. Consequently, the deduction went, it was necessary to increase agricultural production by any means, including the conquest of new territory.46

At the secret conference in which he laid down the schedule for a future war, on 5 November 1937, Hitler explained that the destruction of Czechoslovakia and Austria would be only a first step in a strategy of creating Lebensraum in the East. But the initial conquests would be purged: there would be “forcible emigration” of one million people from Austria, and two million from Czechoslovakia.47

The quest for expansion as a substitute for emigration is most striking in smaller countries such as Poland, given the complete absence of political realism associated with the endeavor. As the map of Europe began to be open to challenge in the 1930s, Poles formulated demands for increased territory as a means to settlement. After the Munich agreement of September 1938, which awarded the Teschen area to Poland in the context of a much more dramatic cession of Czech territories to Germany, the semiofficial Polish newspaper Gazeta Polska spoke about the need to go further and establish a “common Polish-Hungarian frontier.” The Party of National Unity distributed leaflets in Warsaw demanding “the immediate attachment to Poland of all the areas under the Czech yoke,” and the deputy minister for aviation took up the claims for a common frontier with Hungary.48

National frontiers—defended and extended vigorously—would produce genuine communities in a world otherwise threatened by international forces. In this sense, the nation was a defense mechanism against the evils and sins of a global world. A nation could build an improved sense of justice.

A new world of passports and visas was the most obvious manifestation of the generally changing attitudes to migration. The new realities were especially shocking in central and eastern Europe, where large multinational dynastic empires (the Romanov, Ottoman, Habsburg—and also the German Hohenzollern empire) were broken up. In Joseph Roth’s great novel Die Kapuzinergruft (The Vault of the Capuchins) (the burial place of the Habsburg dynasty, perhaps the longest-lasting secular survival of the concept of supranationalism), a seller of horse chestnuts says: “Now we need a visa for each country.” A Polish count then comments: “He is only a chestnut roaster, but he is quite symbolic. Symbolic for the old monarchy. This gentleman once sold his chestnuts everywhere, through half of Europe one might say. And everywhere, where his roasted chestnuts were eaten, was Austria, and the Emperor Francis Joseph reigned. Now there is no chestnut without a visa.”49

The result of the new policies and legislation was a dramatic decline in emigration from those areas with high population increases, and which had figured prominently in the prewar emigration statistics. Large parts of eastern, southeastern, and Mediterranean Europe, where birth rates and the growth of the labor force were very high, now sought alternative strategies for the employment of “surplus population.” The development of industry and a search for export markets was one such approach, but it required an openness of export markets (which was increasingly threatened) and also open capital markets. For Poland, for instance, the growth of the labor force was such that a more than threefold growth in industrial employment (at an annual rate of at least 6.6 percent) would have been needed to absorb it. Given productivity increases, industrial output would have had to rise even faster. But these are difficult targets at the best of times—and in the interwar climate impossible, because of the instability of the export markets and of capital markets.

In the peripheral or industrializing countries with rapidly expanding populations, restrictions on immigration to richer territories depressed wages and prices and made the financial structure more vulnerable to debt deflation. In the industrial countries, the link of demographic developments and depression is not as clear. But they constituted one factor in the demand for the protection and control of labor markets, and in the demand for “national labor.” Restrictive labor practices in turn contributed to the lessened flexibility of labor markets, and hence to a general vulnerability to monetary contraction.