LIFE AT SEA in the Georgian navy was conducted under four levels of regulations: those issued by the various departments of the Admiralty which applied to the whole of the navy; additional general orders issued by the commanders-in-chief of individual fleets which applied to all the ships under their command; additional general orders applying to ships in detached squadrons issued by the squadron commander; and additional instructions issued by the commanding officers of individual ships which applied only to that ship.

The regulations issued by the various subsidiary boards of the Board of Admiralty were known as the Regulations and Instructions Relating to His Majesty’s Service at Sea (hereafter ‘the Regulations’). At irregular intervals, these were gathered together and re-issued in printed and bound form under an Order in Council; each version built on what had gone before and as time went by, each became more elaborate and detailed. For instance, the thirteenth edition, published in 1790, consisted of 232 pages, with a few printed forms bound into the volume at the appropriate places; by 1806 the fourteenth edition had almost doubled to 440 pages with a separate section of 29 forms at the back. These forms, which included such things as muster sheets and pursers’ accounting forms, were also available separately. It was, however, acceptable to use a hand-written version. Although it was the responsibility of each level of commanding officer to ensure that everyone below him adhered to the Regulations, separate chapters were addressed to the relevant commissioned or warrant officers.

General orders given by commanders-in-chief added to the Regulations, partly as a matter of that officer’s personal views on discipline and partly to cover local conditions. These orders were usually issued in the commander-in-chief’s name by the senior captain of the fleet; copies of these orders were entered in a separate letter book where they are typically shown as being addressed to ‘the respective captains’.1 For example, Nelson issued an order on procedures to be followed when obtaining provisions from locations where there was no agent victualler, this order stating firstly that it was the master’s responsibility to check the goods against receipts or bills of lading and to enter details of these transactions in the logbook, which was then to be signed as correct by ‘the Captain or other signing officers’; and secondly that all fresh beef coming on board was to be weighed ‘in the presence of a lieutenant or the master’ before the receipts were signed. A copy of each of these orders would be sent to each captain as it was issued, and a set of them to any new captains who joined the fleet. There were several of these orders immediately after Nelson joined the Mediterranean Fleet in 1803, with others following at longer intervals. This was the normal pattern when any commander-in-chief took over his new command.

One common general order from commanders-in-chief and squadron commanders referred to regular reports on amounts of provisions on each ship. These were usually required weekly and there seem to have been two basic formats: either the specific amount of each species of provision, or the number of days or weeks the items in store would last. Similar reports were required for other types of stores, such as cordage or sailcloth, the numbers of sick with their ailments, and finally the state of the ship itself. The object of this exercise was to allow the senior officer to decide when any particular ship should go into port, or when to organise transports to bring supplies. There are substantial collections of such reports for both Keith and Nelson and it is quite noticeable that the provisions reduce over the weeks and then suddenly increase for all ships at the point at which transports are known to have arrived. This checks out with the logs, and something else which is apparent is that somebody was organising transfers of provisions between ships in a squadron. Ship As logs will show her receiving, say, bread from Ship B and giving beef to Ship C, and at the same time passing pease to Ship B and oatmeal to Ship D. The captains also did it between themselves when the rest of the squadron was elsewhere: Ship E sights a sail which turns out to be Ship F, a signal requests a lieutenant to come aboard and a couple of hours later, some provisions are received or sent across. Almost as often one ship will go off to port for some repairs and bring back supplies for the others; this will most commonly be fresh vegetables or livestock.

Fictional ships’ captains, when not playing whist or the violin, appear to spend all their time directing gunnery drill or engaging in bloody battles. Real ships’ captains, although they did do these things, actually spent a lot of time dealing with administration and paperwork, including that relating to the provisions. As well as checking those weekly reports for the commander-in-chief, which would have been prepared by the purser and, where water was concerned, by the master, and making sure that the appropriate vouchers had been exchanged when stores were passed from ship to ship, he was required to ensure that the right amounts of provisions came aboard in port or from victuallers (but forbidden to stop a victualler bound for another ship). Of course he had a clerk to do the main part of this work but his was the ultimate responsibility and his the salary that could have an imprest placed against it if the paperwork did not tie up.

The principle of imprests was one which operated throughout the Royal Navy, from warrant officers to admirals and from agents victualler to major contractors. Every time a financial transaction took place, the cost was charged to someone’s salary or business account and stayed there until their accounts could be passed. When the captain decreed an extra issue of wine for the sick, it was charged to his salary. When an agent victualler abroad made a local purchase and paid for it by a Bill of Exchange, as soon as the Bill had been presented to the Victualling Board and paid, that amount was charged to the agent victualler’s salary. When a victualling contractor like Basil Cochrane bought supplies with his own money, that amount was the subject of an imprest to his account. The system operated on a ‘guilty until proven innocent’ basis, and proving your innocence could take many years. In the middle of the argument with Basil Cochrane, the Victualling Board remarked to the Admiralty that it was their practice not to finalise accounts until the agency was closed. Basil Cochrane’s agency opened in 1796 and closed in 1806, by which time his account bore an imprest totalling £1,418,236.6.9. In that year, the total amount of imprests on agents and storekeeper’s accounts alone (ie not counting pursers or captains) was almost £11,000,000.2

The same principle was applied to warrant and commissioned officers. Their account started when the ship was commissioned or when they joined her, and did not cease until the ship was paid off, which could be many years later. Everyone was meant to submit quarterly accounts, but because the Victualling Board insisted on seeing original documents, and because no-one with any sense was going to risk sending those off by another ship which might be captured or suffer other disasters, those accounts went off with copy vouchers and sat in the Victualling Office limbo for years until the originals could be produced. Add to that the Victualling Board’s insistence on seeing and finalising both sides of every transaction and you get, as we saw with Heatley in Chapter 2, a situation where dozens of pursers’ accounts were held up because those of the agent victualler were not finalised. Small wonder that barely a day went by without the letter files containing a plea from some officer (or his widow or executors) for his accounts to be passed despite missing vouchers. (For more information on Bills of Exchange and imprest accounts, see Appendix 5.)

Another little bit of penny-pinching from the Victualling Board was their reluctance to allow the possibility of accidents. If, say the Regulations, through the carelessness of the men handling it, some item of provisions was lost when coming aboard, it was to be charged to their wages. This happened on Leviathan in 1804, when a bag of bread was dropped between boat and ship, a common enough situation when two men were tossing it and one let go too soon. The fuss about this went on for days, while the rescued bagful was spread out to dry and inspected and a decision made on how much was still usable.3 And all of this, of course, was the captain’s problem, as he had to make the decision on who to charge and how much, and then pass a voucher to the purser who also had to account for it. It was also technically the captain’s decision, when pork ran short, to declare that beef should be served instead; of course what really happened here was that the purser would report on the shortage and suggest the substitute and the captain would give him a written order to do it. The same applied when overall shortages occurred and food had to be rationed.

The final aspects of the provisions which required the captain’s attention were those relating to quality and fairness. He had to see that certain items, such as biscuit, were checked over regularly and any incipient problems dealt with; to ensure that food was shared out fairly (especially fresh meat); and generally ensure that the men were fed properly. A common entry in captains’ orders is one that says when a cooked meal is about to be served, a portion is first to be taken to the officer of the watch for sampling. Quite what should have happened if that sample was declared inedible is not stated but one can imagine the panic and demands for the keys to the cheese store!

The captain’s orders were entered in the ship’s order book, which was kept where it was available to anyone who wanted to read it – often attached to the binnacle. These orders expanded on the Regulations, and typically would state the times at which food was to be issued and who was to hold the keys to various storerooms. Officers were expected to be familiar with the whole and many kept their own copies of the portions which covered their personal responsibilities.4 As above, there was typically a flurry of new orders when a new captain took over a ship, with the number and type of orders depending very much on the character of the captain. Those from Prince William Henry (later to be William IV), who was a real control-freak, run to many more pages than the normal and amongst other nit-picking, require everybody, including the senior lieutenants, to ask for permission every time they wanted to leave the ship.5

For the master, the Regulations which outline his duties with regard to the provisions appear, on the face of it, to be quite simple, covering the receipt and stowage of provisions and liquids, seeing them brought up from the hold and observing the quantities present when casks or bags were opened or fresh meat brought on board, having responsibility for the spirit room and making a daily report to the captain on the quantities of beer and water consumed and the amount remaining. The reality was far more complex.

The easiest of these tasks was checking that the quantities within casks tallied with the quantities marked on the outside. A group of officers assembled for this job: the master, a lieutenant, the purser and perhaps the boatswain. The cask would be opened and the contents carefully checked. With beef or pork it was simply a matter of counting the pieces and recording them in the purser’s journal and the ship’s logs: for instance ‘opened 3 casks pork of 50 pieces, No 12 5lb short, No 13 5lb short, No 14 4lb short; opened 1 cask beef No 2154, 38 pieces, 12lb over’. This would be done in the vicinity of the galley and the pieces would go into the steep tubs under the cook’s eye. Other provisions would be opened in the purser’s steward’s room, transferring them into different containers and weighing them in the process, using a steelyard suspended from a beam. Again, shortages or excessive quantities were recorded in the logs and purser’s journal. Miscounts of contents in meat casks are very frequent, too many pieces in the cask being almost as common as too few. To take just one example, on Triumph, between July 1803 and June 1804, the master reported opening ninety-one casks of meat; only one contained the weight marked on the exterior; twenty-three were overweight (by up to fourteen pounds for the pork, thirty-two for the beef) and sixty-seven were underweight (by up to twenty pounds for the pork, thirty-two pounds for the beef).6

Exactly how liquids were measured when casks were opened has not been recorded; it could have been with a dip-stick, or by emptying the cask from the bung into a measuring jug. There might have been some temptation to broach beer casks and steal the contents; there would have been far more with wine or spirits. One sequence of reports of wine in Triumph does cause one to wonder just what was going on. In December 1803, after receiving a sequence of complaints about faulty casks delivered by one particular transport, Nelson had issued a general order that the contents of every cask was to be measured and recorded in the log book when it was opened.7 Between 3 February and 4 July 1804 Triumph reported twenty-six faulty casks with losses of between four and eleven gallons. The reasons given, although acceptable at first, begin as time goes on to sound rather like the increasingly unlikely excuses of ‘food poisoning’ or ‘migraine’ which alcoholics offer as a reason for not turning up at work on Mondays: ‘split stave’, ‘broke stave’, ‘bad joint in head’, ‘bad knot in stave’. After a while, you begin to wonder whether Nelson’s warning about faulty casks had provided a convenient excuse for pilferage. Most of the losses were under six gallons, and they did not increase consistently as time passed as one might expect from casks which were faulty when received. Equally, one might expect after the first few were found that the master and purser would have had the whole lot up to inspect and measure, but there is no indication that this was done.

Spirits were less easy than wine or beer for the unauthorised to get at. A clever petty officer could, however, organise himself a supply of extra grog by taking charge of the empty spirit cask after its contents had been issued. Filled with fresh water and left for a couple of days, the remains of the spirits in the wood would permeate the water and produce quite a strong liquor. A wise purser would see the empty casks rinsed out with salt water and left on deck to air; there was otherwise a risk of explosion from the vapour if the bung was removed with a candle close by.8 Fully aware of the risks, both to the spirits from thieves and from the spirits themselves as a fire risk, the Regulations required that they were kept in a separate spirit room which, like the powder room, was fully lined and plastered and lit from a separate light room, and that it was kept locked except at the specific times stated for issue. No lights were allowed in the spirit room itself, and spirits were only allowed to be served on the open deck, in daylight and with no candles in the vicinity.9

It was at this point, of opening up containers of provisions, that most of the quality problems would be found. The procedure in such cases was that the container would be set aside, or if spirits, marked and returned to the spirit room, until a survey could be arranged. The term ‘survey’ was used in several ways: it could mean a stock-take; it could mean inspecting something to see if it was worn out and no longer usable, as in the case of an old sail (or even a sick human being), or defective and unusable, as in the case of provisions. In each case, the survey would be carried out by three commissioned or warrant officers, usually from other ships. For such things as boatswains’, carpenters’ or sailmakers’ stores, it would be three of that sort of warrant officer; for the sick, it would be three surgeons; for a purser’s stores it was more likely to three masters, perhaps because it was felt that they would be less sympathetic to misdemeanours. Whatever the type of item to be surveyed, its nominal ‘owner’ would ask the captain for a survey to be carried out and he arranged for the relevant officers to come aboard and do the survey. With provisions, if they agreed the items were inedible, they signed a formally-worded statement to that effect. Occasionally, when these provisions were so bad they were ‘stinking, rotten and a nuisance to the ship’, they would be thrown overboard, but otherwise they were supposed to be returned to victualling yard stores at the next opportunity. Some items, such as butter or ox-hides from beasts slaughtered on board, were meant to be offered for the boatswain’s use.

The next part of the master’s duties with provisions was to see them brought on board and check quantities against the receipts or bills of lading. Sometimes they would be delivered to the ship by a hoy, other times a boat or party of men had to be sent to collect them, under the charge of a lieutenant or midshipman. Small casks and bags of bread or vegetables could be carried in a pinnace but for larger casks and large quantities of supplies, the launch or longboat would be used.10 Logs frequently report receiving provisions by the launch or sending the launch to transports for provisions.

It has been suggested that seamen’s skills were adequate to make direct ship-to-ship transfers of provisions; this is theoretically possible, using cables and ‘traveller’ blocks. It would, however, require a level sea, a high degree of seamanship and two captains with nerves of steel and the certainty of a forgiving commander-in-chief.

Spirits, as we have seen, were kept in a separate locked room. This was usually situated aft, under the cockpit; as well as being locked it would also have a marine posted to guard it. In the days when salt or dried fish were carried, this would be in a separate room, also aft. Even after fish was dropped from the official ration, the fish room retained its name, although it tended to be used as a coal store. Bread (ie biscuit) was kept in the bread room, right aft, where the shape of the hull kept it sufficiently high up to be clear of bilge water.

Everything else, from water to raisins (with the exception of fresh meat and possibly vegetables and fruit) was kept in the hold; exactly where required the master to exercise some skill if the trim of the ship was not to be adversely affected. Consider the weight of provisions and beverages that had to be carried, and the not inconsiderable weight of the casks themselves (tare weight), and you can appreciate the magnitude of the problem.11 The basic ration works out at about eleven pounds per man per day, but to this you must add the weight of brine in the meat casks and the water needed for steeping and cooking. These are difficult to calculate, but a total per day, including these, of fifteen pounds would not be unreasonable. Multiply this figure by the number of men on a ship and the time for which they must be provisioned, and you get this result:

These are speculative figures, but can be more or less confirmed by a list of provisions carried by the frigate Doris when she set off for the west coast of South America in 1821. Stored for 240 men for four months, she carried 107 tons of water, 14 tons of biscuit, 12 tons of salt meat (plus, of course, an unspecified amount of brine), about 4 tons of pease, oatmeal, sugar, cocoa, lime and lemon juice and tobacco, and just short of 6 tons of spirits; a total of 141 tons. She also called at Madeira en route, where she picked up 10 pipes (4 tons) of wine.12

Although the figures for the sloop are considerably less than those for a First Rate, the comparative sizes of the ships made them just as important. The master’s problem is two-fold: keeping the ship trimmed, and at the correct draught, both essential to preserving the ship’s sailing qualities. The problem of trim required everything to be stowed so that each day’s removals balanced out over the course of a few days; for this the master would direct exactly what was stowed where, keeping in mind the rule of ‘oldest to be used first’, and then direct which items were to be taken out each day. They must all have drawn up plans of this stowage; some of them copied these plans into their logs.

The draught problem could be extreme. Consume too much of the hold’s contents and the ship will lighten and rise in the water, becoming, since she carries a lot of weight in her guns, top-heavy and at risk of capsizing in rough weather. However, there was plenty of handy stuff to correct the problem: seawater. Many logs report filling water casks with seawater when the fresh water is getting low. One wonders to what extent they then flushed out these casks after emptying the salt water, or whether they just drank it slightly brackish. It cannot have tasted any worse than some of the stuff they got from Deptford Creek (although they did finally pipe water in from the Ravensbourne, a small river which ran into Deptford Creek above the tidal level).

The basic rule on stowage was to keep the largest casks at the lowest level. The bottom of each hold was ballasted, first with pigs of iron and then with a layer of shingle, deep enough for the bottom tier of casks to nestle in. The ideal was ‘bung up and bilge free’ (the bung being in the widest part of the cask), but the shingle would inevitably become wet and often foul. Quite apart from the water continually making its way down the ship (and consider the state of the water that came off an anchor cable which had been lying on the bottom of a harbour where every ships head vented into the water), there must have been many men who, although this was strictly forbidden, found shingle ballast more inviting than the seats of ease exposed to the weather. There are stories of noxious gases being generated, so powerful that men in the hold would be overcome by them. It was another of the master’s responsibilities to ensure that the shingle ballast was ‘clean and sweet’. There were only two ways to do this: let in seawater and pump it out again, as many times as it took to flush all the foulness out, or remove all the shingle and replace it with fresh. This laborious task, which involved shovels and baskets, was slow work. On one occasion when the masters log for Victory reports this operation (emptying first one hold completely and reballasting, then moving the stores before repeating the exercise with the other), she dumped almost seventy tons of shingle ballast overboard before restowing her holds, and the operation took five days to complete.13 At the same time, she refilled all her water casks to the total capacity of 315 tons.

Casks were stowed in rows lengthways down the hold, with perhaps a few crossways at either end. Once the bottom tier was in place, a second tier of smaller casks could be put on top in between the rows, wedged in to stop them shifting. There would be three or four rows in the bottom tier and there might, on larger ships, be a third tier on top. The smaller ships may not have used the larger sizes of casks.

Despite the ‘bilge free’ ideal, that bottom tier of water casks would be almost permanently lying in wet shingle. This must have led to early deterioration and would explain the constant plaint from commanders-in-chief on all stations of the difficulties of maintaining stocks of water- and wine-casks, this despite the rule that ships going on foreign service were to be supplied with new casks. The Victualling Board were very fussy about casks; water- and wine-casks were never to be ‘shaken’ (ie taken to pieces) except in absolute necessity’ and then must be bundled with their hoops and labelled so they could be reassembled easily. It was undesirable to shake other casks, but often necessary to make it possible to get at the middle row of water casks. It is often suggested that food casks were automatically shaken to save space but on reflection, with the exception above, space may not have been an issue. You mainly need space to put supplies in, those supplies are going to come already packed in casks, in which case you can dispose of the empties and get a bigger credit for them if they are whole and the recipient does not have to pay a cooper to reassemble them. Of course, ships which were carrying such large quantities of supplies that they could not fit them all in the hold (for instance those going on very long voyages, or carrying troops) would store these on the decks, use these first and then shake them; others might do it when needing space to clear for action.

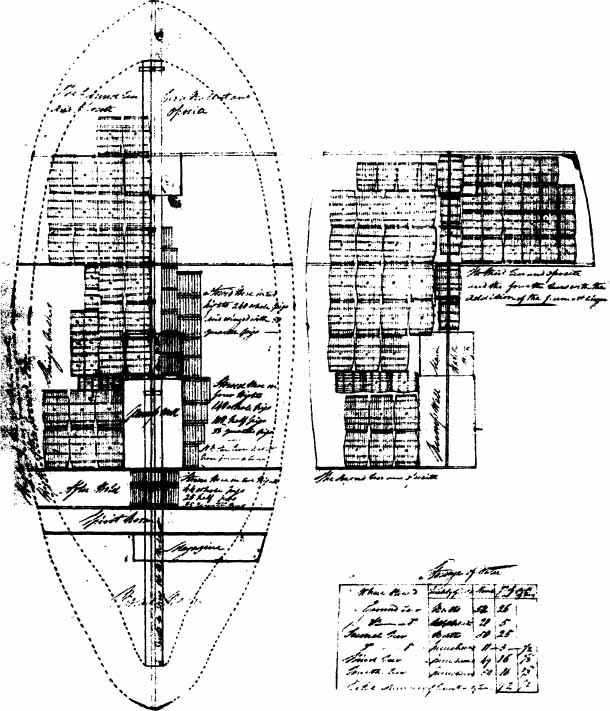

The traditional method of stowing the hold (left) and orlop deck in the frigate Galatea, December 1802. Stowage was clearly dominated by the weight and volume of the laden casks – in this configuration the ship stowed a total of 92½ tons of water – which was vitally important for the trim and stability of the ship, and hence its sailing qualities. (PRO Adm 95/41)

Theoretically, most ships, especially the larger ones, had a cooper on board. There is a special pay rate for them shown in the Regulations and sometimes a commander-in-chief mentions them in his correspondence; for instance, Sir James Borlase Warren offered to lend the flagship’s cooper to the victualling yard for a few days when he was on the North America station in 1808.14 However, there are also some remarks in the Victualling Board papers about the difficulty of persuading coopers to volunteer, given that they were in a ‘reserved’ occupation on a high wage, and a survey of muster and pay books for line-of-battle ships and frigates found them listed on less than a third of the ships, and those not necessarily First Rates.15 This does not mean no-one ever touched the casks when there was no qualified cooper on board – any competent carpenter can do what is necessary to remove the head from a barrel and put it back, and shaking a cask is simplicity itself – but it takes a very skilled man with special equipment to put a set of staves and hoops together to produce a watertight cask. Perhaps the rule was to provide coopers in only sufficient numbers to do this for a whole squadron, although a cooper’s duties would have included making small tubs and buckets for use in the sick-bay and elsewhere.

One other thought which comes to mind about water casks is the business of ‘starting’ the water as a method, much loved by writers of naval fiction, of quickly lightening the ship when chasing or being chased. The theory of this is that you start the casks in the hold and then pump the water out using the ships’ main pumps. However, given that the casks were stored, as we saw above, bung up, one suspects that there was only one way to empty them quickly and that was to take an axe to them. Because they were stowed end to end, it would not be possible to knock in the heads, so it would have to be the staves that went; however, this could only be done with the specific (ie documented) instructions of the captain.16

Each ship had two or more holds, although these would not necessarily be partitioned off. Goods access was through a series of hatches one above the other, through which casks in slings could be lowered by a system of pulleys from the yards or booms above. The general assumption is that water casks came up when they were empty and either new full ones went back down (certainly this happened when a transport brought water) or the empty ones were taken off in boats to a watering place. However, whilst it is all very well to hoist a 250-gallon leaguer into the hold with the aid of pulleys, it is quite another matter to get that full leaguer into a boat from the shore, although there were various methods of doing this. Wybourn reports a watering party at the Maddalena Islands using a triangle to hoist the casks into boats,17 while other possibilities were rolling them up a plank, or ‘rafting’ (ie towing them) out to the ship. Given the ever-present risk of hernias one wonders if watering parties used smaller casks and decanted the contents into the leaguers with pumps and pipes. They certainly had to do this once iron water tanks were introduced, as these were too big and too heavy when full to think of moving them.

The stowage of a frigate’s hold after the introduction of iron water tanks, 1812. The tanks held about 400 gallons, far more than even the largest cask, but the real advantage was the lack of wasted space in a tier of close-fitting iron cubes, unlike barrels which even when nested left much of the overall volume unused. (PRO Adm 106/3122)

There is a slight mystery about water tanks. The concept appears to have been suggested to the Victualling Board for the first time in March 1809, when Messrs Richard Trevithick and Robert Richardson sent in a printed abstract of their patent, dated 10 February 1809.18 This does not include any drawings, remarking instead that the tanks could be of any shape, but goes into great detail of how much space and weight they would save when compared with wooden casks, not to mention solving the difficulties of obtaining suitable wood for staves. They are also, they say, proof against rats, weevils, cockroaches and thieves, and they advocate their use for all sorts of cargo and dry foodstuffs as well as liquids. The Victualling Board reported on this to the Admiralty, remarked that they had consulted Sir Joseph Banks who approved the idea, and suggested that trials should be conducted. The endorsement (one of those delightful scrawls on the back of a turned-over corner of the page) from the Admiralty Secretary Sir William Wesley Pole, shows that the Admiralty agreed with this suggestion and instructed the Victualling Board to carry on.

All this indicates that water tanks were a new idea to the Victualling Board, and yet in 1796 Samuel Bentham designed two experimental ships, Dartand Arrow, which, as well as being fitted with solid bulkheads and drop keels, had large iron water tanks. (Bentham was awarded a Gold Medal of the Society of Arts in 1800 for this innovation.19) These may have been too troublesome to consider seriously at the time; in June 1804, Nelson wrote to Captain Vincent of Arrow that while he was in Valetta, ‘If the tanks cannot be repaired, water casks must be substituted in their room’20 Unfortunately no detailed documentation of the problem with these tanks has survived, but we do know that there were eight of them, each holding 40 tons of water and that they were fixed in place; this may have been why they were not generally adopted. Arrow did not make it home in 1804, falling victim to a larger French ship, and so there are no dockyard records of the repairs needed.

When they were accepted as a good idea, water tanks superseded the old wooden casks in the hold quite quickly, the Victualling Board ordering them in batches of one or two hundred at a time, a transition that was speeded up in 1812 when Truscott’s pump was officially introduced. This pump, or one like it, had been in use since at least 1805 and as well as merely getting water in and out of the tanks it could be fitted to a system of flexible leather tubes so water could be pumped straight to the galley coppers or into a tank on deck. This was not entirely good news: these wooden deck tanks, which replaced the old scuttle butt, were lined with lead, but despite the protests of some captains that this was a health hazard, the Admiralty could see no reason to discontinue their use.21 Another of those details which, irritatingly, are never mentioned is how they got water up for use before suction pumps were available. It can only have been done by hoisting the casks up in slings and then, perhaps, they had some sort of rigid stand for them to sit in while the contents were tapped off for the scuttle butt or the galley boilers.

Gradually all ports organised water pipes out to jetties where ships could tie up and use their pumps, but until then there was still the task of getting water on board from ad hoc watering places; this could only be done with wooden casks and manpower. There were other hazards for these watering parties besides muscle strains and ruptures. Other than at the occasional spring which flowed out of a cliff-face, watering places tended to be marshy and infested by mosquitoes. Despite a merchant captain having remarked on the connection between mosquito bites and malaria as early as 1572, the medical profession had ignored or forgotten this; but without realising that it was the marsh-dwelling mosquitoes which carried malaria and yellow fever, naval surgeons were aware that marshes were unhealthy places.22 Dr Snipe, Physician to the Mediterranean Fleet, had told Nelson that the men were at risk and recommended that ‘as a preventative against the disease which the men are subject to [when watering in marshy places]’ they should be given a dose of Peruvian-bark [quinine] in a preparation of good sound wine or spirits’ and Nelson issued a general order to this effect. Another hazard was the local inhabitants: elsewhere in Sardinia the peasants made a practice of plying the watering parties with wine in the hopes of getting them so drunk that they would not notice the casks disappearing.23

The last of the provisions tasks falling to the master was to observe, with a lieutenant and a mate, the cutting-up of fresh meat. Whether this was meat bought on shore or from beasts slaughtered on board, the Regulations specified that it should be cut up ‘in some convenient and publick part of the ship, open to the view of the company’.24

It is not known exactly where vegetables and fruit were stowed. They might have been put in empty casks in the hold, where the casks would keep the rats out. Most would have arrived in nets or bags, in which case they might have been hung up near the galley. In general they do not appear to have been acquired in such large quantities that they needed stowing at all, as they would have been consumed in a few days. Some log entries show onions being ‘served out to the men’ within a few hours of arriving on board.

Although not specified in the Regulations, the master would have had some involvement when livestock was brought on board, especially when large numbers were involved. Even a small live bullock would weigh about half a ton, so sixty or seventy of them would need careful positioning. The matter of getting them on board would, in itself, require some expertise where no jetty was available. With a jetty they could be herded up an enclosed gangway; without one, they would have to be slung on board, which means you first have to get them onto a boat, while leaving enough room to row it, or swim them out to the ship, having first attached some ropes to facilitate fixing the slings under their bellies (one hopes they did not lift them by their horns) and to keep their horned heads under control during the whole procedure. Alas, there was no way to control the other end, given the propensity of alarmed beasts to void their bowels, the only consolation being the availability of plenty of water to sluice down the decks.

Sheep and pigs, of course, are much easier to deal with because they are smaller and lighter than a bullock. A strong man can pick up a sheep or pig fairly easily, especially if he can catch it unawares. Several could be carried on a boat, confined under a net and at a pinch they could be hoisted on board in a strong net. By the same virtue of their size, these smaller animals were easily accommodated on board. The carpenter built pens for sheep on the centre line, usually between the capstan and the main hatch, made so that the lower section of the pen could be pulled out for easier deck cleaning (not a major problem with sheep whose droppings are fairly dry and small).25 There are also several references to sheep being kept in the boats, although this cannot have been on a long-term basis. Pigs needed a more solidly constructed sty. This was traditionally under the forecastle but in 1801, at the instigation of the surgeons, the pigs were moved to the waist and the sickbay took over the space vacated. The pigs seem to have been allowed out for a run at intervals; there are journal reports of them wandering the deck and even eating clothing which had been left lying about. With the exception of such ships as Pasley’s Sybil (see page 19) there were probably never that many of them but they tended to be kept longer than other beasts, often purchased as piglets and kept until they were big enough to make a series of good meals. Since they were not the ship’s property the logs do not record their acquisition or their food, although on one occasion in the Mediterranean, when a merchant ship with a cargo of acorns was captured, the acorns were shared out among the squadron. In this situation the acorns are most likely to have gone to the pigs, but they were probably being carried by the merchantman to sell for human consumption; it is difficult to think that they had sufficient value for any other purpose to make it worthwhile carrying them. They were probably acorns of the holm oak (Quercus ilex var. rotundifolia) which are prized for their chestnut-like flavour and are cultivated in parts of Spain and Portugal.

Many ships also had a goat, kept for its milk. There are pictures of these loose on the quarterdeck during the day, but they probably spent the night with the sheep. Poultry were also kept on most ships, or at least at the beginning of the voyage. They belonged mainly to the officers and were kept partly for eggs and partly to eat. They were kept in coops which were brought up on deck during the day; they can be seen in old pictures, fitted with vertical bars in front and a trough below, so the birds could put their heads out to peck. In 1815, new instructions were issued to the dockyards to construct permanent poultry coops in the waist ‘in lieu of the moveable coops now in use’; captains of frigates could site theirs on the quarterdeck.26 The poultry would have fed on corn, crumbs and, no doubt, the beetle larvae known as bargemen. There are a couple of stories of cockerels escaping when their coops were shattered in battle, one at the Glorious First of June and another during the Battle of St Domingo; each took up a perch to crow throughout the battle, and thereby no doubt managing in the process to change their status from potential meal to much-loved ship’s mascot.

It is possible, but unlikely, that sheep or even pigs might be housed in the manger, the area round the hawse-holes where the anchor cables came inboard. The manger was separated from the rest of the deck by a solid barrier whose purpose was to prevent water from the cables swilling round the deck. Because this area, to the uneducated eye, seems a likely place to confine animals, popular opinion believes this is where they were kept. It would, however, be difficult to get cattle into the manger without hoisting them in, and even more difficult to keep them there, quite apart from the question of what you do when anchor cables are in motion. Some pigs do seem to have been kept in the manger, although probably only on a temporary basis: Liardet remarked on the pigs ‘[disputing] the right to the manger with the fore-topmen when working the cables’, the agile topmen being chosen to pass the nippers when heaving in the cable.27 Another suggestion is that the manger was used to store fodder, citing the case of the Boyne, which is supposed to have caught fire when the hay in the manger spontaneously combusted, but this is not correct.28 Another case where a ship was destroyed by fire was that of Queen Charlotte. In her case the fire was caused by loose hay coming into contact with a lighted slow-match in a match tub outside the admiral’s cabin (ie aft). Of interest here is that the hay was being moved to be bagged and ‘pressed’, thus compressing it to take up less space. (Also of interest, although perhaps a non sequitur, is that one of the officers, when reporting events at the court martial, stated that on being informed that the ship was on fire, he replied ‘God bless me, where?’. One suspects that what he actually said was something quite different!)29 As a regular practice, storing hay, or anything else, in the manger, once again ignores the question of what you do when you need to weigh anchor.

The new standard pattern of poultry coop introduced in 1815. (PRO Adm 106/3574)

So where did they keep the cattle? One or two could be tucked away in a number of places, ideally, one assumes, close to a scuttle where the deck could be swilled down. Large numbers were another matter. The accounts of Thomas Alldridge, arranging cattle for the fleet off Egypt in 1798, include an entry for wood and battens and the fees for carpenters to nail them ‘to prevent the bullocks falling to leeward’; this indicates that they may have been amidships somewhere. But the best indication of common practice is the story of the unfortunate Amazon in 1804, when Nelson asked her captain, William Parker, to collect sixty cattle and thirty sheep for the squadron off Toulon. ‘Unfortunate’ because Parker and his crew took great pride in their ship and she had just been in port for repairs, finishing off with a repaint. But when Nelson asks for a favour, how can you refuse? The cattle were taken on board and tied between the guns, heads to the ship’s side and tails to the centre, and there they stayed for several days until they could be shared out among the squadron. Glascock also reports a seaman yarning about the Glorious First of June and remarking, ‘we’d three or four bullocks twixt the guns on the main deck’, so perhaps that was the standard solution to the problem. They would have been able to secure the bullocks fairly tightly, thus solving the problems of keeping them upright in rough seas and preventing their milling about dangerously in a panic (undesirable behaviour from animals armed with horns). It would also explain why cattle were thrown overboard before going into action, as Zealous did before the Battle of the Nile.30 There are several unanswered questions attached to this: if the men usually ate at mess tables between the guns, what did they do when there were cattle there, how did they practice gunnery, and did they use cleaning the deck as a punishment duty?

The final question about cattle and sheep on board is that of feed and water. Some of the log entries which report taking on cattle also mention fodder, as do some of the accounts of the agents victualler afloat. But since they use such vague terms as ‘bags of fodder’ or ‘bundles of hay’ it is impossible to know how much fodder was bought and how long it lasted. Nelson once testily enquired why so much fodder had been bought for cattle that were soon to be slaughtered but in general the amounts listed do not seem like a lot: two or three bundles for twenty or thirty beasts. There must have been a fine line to draw between common humanity, restless hungry cattle, and the hope that reducing input will also reduce output.

Another area on which information is sparse is that of slaughtering animals on board ship. What follows is, therefore, a resumé of the processes on land, with some suggestions as to how the process might have been done on board ship. With pigs or sheep, you restrain them, pull back their head and slit their throat, then hoist them up by the back legs to drain the blood. On board ship, there were plenty of beams high enough for this purpose, and one assumes that a piece of old sailcloth would have been spread out to protect the deck and a tub used to catch the blood. Bullock carcasses, being bigger, would have needed something higher than a deck beam to hang from, so this was probably done on the weather deck using a yard or tackle from the main stay. With bullocks, the process starts with pulling their head down and hitting them, very hard, on the forehead with the blunt end of a pole-axe, then once they are down, using the sharp end to finish them off before cutting their throats. Once the bleeding has stopped, the next step with a pig is to immerse it in scalding water and scrape off the bristles before hoisting it up again. After this, all the beasts were gutted (as with the blood, presumably into a tub) and the sheep and cattle were skinned; this is most easily done when the carcass is warm. The carcass was then left to cool for several hours before cutting it up. Pig skin stays on the meat; as we will see in the next chapter, they had facilities for roasting and would not have wanted to forego the crackling.

The tallow was scraped off the skins and collected to be sold, with the oxhides, at the next opportunity. These hides were obviously only rudimentarily dressed, as there are many reports of their becoming maggoty and stinking. Sometimes they became so noisome that they were declared ‘a nuisance to the ship’ and dumped overboard. Although not specifically mentioned in any of the logs or accounts the author has seen, the sheepskins may also have been sold on shore. On the other hand, there are many things you can do with a sheepskin, from making warm waistcoats to padding a damaged limb, assuming that you have someone on board who knows how to dress the skin. There are other usable by-products; the horns of the cattle could have been used for powder-horns or to make drinking mugs, and sheep’s knucklebones are traditionally used as gaming pieces or dice.

To what extent they had experienced butchers on board is not known but at a time when many beasts were killed on the farm it would not have been difficult to find a crew member who knew what to do; the author has not seen any listed as such in muster or pay books. How much of the offal was used would also depend on whether anyone knew how to deal with it, and, perhaps, weather conditions; cleaning-out intestines to make sausage skins without damaging them would not have been easy in a rough sea. Mentions of any specific pieces of meat are rare but Jack Nastyface mentions feasting on bullock liver fried with salt pork and St Vincent ordered his officers to take the heads as their share, as a good example.31 This makes one wonder whether the crew were inclined to refuse this sort of meat; certainly most of it needs more complicated preparation than simple boiling.

Captain, master and lieutenants had some involvement with the handling of provisions; the purser spent most of his time on them and was responsible for them financially. He was a combination of paid employee and entrepreneurial businessman, allowed to sell certain items to the crew. He was appointed by warrant, which meant that unlike the commissioned officers, who could move from one ship to another comparatively easily (often following the senior officer whom they regarded as their patron), he tended to stay with one ship for many years. The main reason a purser would want to move ship would be to get into a higher-rated ship and thus increase the magnitude of his ‘business’ as well as his salary. Until 1782 they had been allowed to go straight into the higher-rated ships, but Sandwich, as First Lord of the Admiralty, put a stop to this, insisting that pursers started their career in a sloop.32 In 1813 an order was issued that pursers had to pass an examination by three experienced pursers before obtaining their warrants.33 In theory the purser’s accounts from one ship had to be passed before he was appointed to another; in practice the Victualling Board would not block his appointment unless they suspected him of fraud or he had a big debt with them. Even then, if they saw no other way of recovering his debt they would allow him to go to a new ship.

Before obtaining his warrant, the purser had to find two other people to stand as surety for him, in amounts relating to the rate of the ship: starting at £1200 for a First Rate and reducing to £400 for a Sixth Rate or sloop. However, ‘For encouraging him to a zealous and faithful discharge of his duty’, after his accounts were passed, in addition to the wages for himself and his servant he received a commission based on the amounts of provisions he had dispensed, ranging from tuppence per pound of cheese to three shillings per bushel of pease. His wages were not over-generous: he received an amount related to the rate of the ship; in 1790 this was set at £4 per lunar month for a First Rate, reducing to £2 for a Sixth Rate, then in 1806 this was increased to £4.16.0 reducing to £3.1.0. In all Rates he was allowed a steward, in First to Fourth Rates his steward was allowed a mate.34

As well as accounting for all the food that came onto the ship, the purser had to account for its use on a ‘per man, per day’ level. He had to keep a copy of the muster book, noting when each man joined or left the ship and why; when they were away on duty (perhaps manning a prize) and when they were taken to the sick bay, at which point they were fed on a different basis. The purser also had charge of slop clothing, beds and tobacco; the men had to pay for these, by deduction from their wages. If they wanted more tobacco than their normal ration, the purser was allowed to sell it to them from his private stock. All of these items, except the private stock, had not only to be noted against each man’s name in the purser’s muster book, but in a sequence of other books: an appearance (ie joining the ship) and discharge book for all men, a book of all sick men sent out of the ship, a slop book, a tobacco book, and a book detailing every cask or package of provisions brought aboard, with full details of the identifying marks on each so the origin of defective items could be identified, and separate lists of all these defective items together with the formal certified documents of survey condemning them as not fit for men to eat’.

Finally he had to keep receipts for, and details of, purchases and issues of ‘necessaries’. This term covered all items which were either not supplied through victualling yards or for some reason had to be bought on the open market, such as candles, ‘lanthorns’, turneryware (wooden utensils for the men to eat from) and coal. For all these items he was allowed a sum of between fourteen and seventeen pence per man per lunar month, depending on the size of the ship and the categories of men involved. He could either draw cash for necessary purchases from an agent victualler, or when away from a victualling port, could draw Bills of Exchange on the Victualling Board if supported by his captain, using the same method to purchase fresh meat and vegetables.

All of this was comparatively easy when in home waters, where most of a ship’s requirements could be obtained from the outports and the rest purchased in sterling. It was when abroad that the documentation became more complex. Victualling yards were fewer and thus more items would have to be purchased from local merchants, each transaction requiring certification from two or three ‘principal inhabitants’ (one of whom would ideally be the local governor or consul) that the amount paid was the current market price. In addition, full details had to be given of the currency used and its exchange rate at the time of the transaction, this also requiring certification. For larger transactions and where the seller was amenable, the purser could pay by drawing a Bill of Exchange on the Victualling Board. The preferred format for these and an explanation of how the Bill system worked is shown in Appendix 5.

Finally, whether in home or foreign waters, the purser had to keep full stock records. When he joined or left a ship, a ‘survey’ or full stock-take of all his stores had to be performed and certified by three warrant officers; when the commission was completed and the ship laid up, all the remaining provisions had to be returned to the victualling stores and he had to accompany them to see them properly received and accounted for. And of course, whenever ships passed provisions between them, both pursers had to prepare and exchange ‘warrants’ and ‘distinct accounts’ of those transactions.

If for any reason any species of provisions were not available, or were refused by the men as being bad, or if provisions were saved for other reasons such as the boys receiving less than the full allowance of wine or spirits, the purser had to keep track of the value of these provisions and pay it over to the men in cash, theoretically at no greater than quarterly intervals. This ‘short allowance’ money was considered sufficiently important to warrant its own chapter and printed form in the Regulations. It was to be paid in cash, at sterling value but in local currency, with the men having the benefit of the exchange and the money was to be paid to each individual in person, regardless of debt notes or other financial obligations. This is probably how the men obtained the money which they would spend on shore or when the bumboats came calling.

This makes it appear that the purser’s life was, if complex from an accounting point of view, at least safe financially: provisions were either expended by issuing them to the men or declared inedible and the subject of an accounting credit. Alas, poor purser, the Victualling Board were not that generous. Even after the Spithead mutiny, when he was officially allowed a margin for wastage, he only received that allowance after his accounts were passed, not before to make up any shortages. There were also various situations in which he did not receive any allowances. Leakage of wine or spirits or oil once the casks had been checked on receipt were considered to be his personal problem and he might even be refused credit for items which had been legitimately surveyed and condemned: one unfortunate purser produced survey certificates for a large quantity of bread which had been eaten by cockroaches, but the Victualling Board refused him any credit, on the grounds that this might create a dangerous precedent. Nor, if he was bulk-buying at a non-victualling port and needed to store his purchases, could he claim for the cost of that storage, or for hiring boats. Small wonder that albatrosses, with their propensity for following ships for days on end, were said to be the souls of dead pursers, desperately seeking a ship that would allow them to recover their losses.

Many pursers, no doubt, did resort to sharp practice to make ends meet. It is not unusual to find them being court-martialled for fiddling their vouchers or even being prosecuted by the Victualling Board for various frauds. There are many time-honoured ways of building up a ‘reserve’ stock of items to replace those lost by accident: for instance, one wonders what quantities of items which were reported as damaged in battle were reserves of this sort. A good purser who was a competent book-keeper did not have to resort to such things, and could rise up the career ladder from small ship to large one; a few made the next step from purser to agent victualler at one of the victualling ports; some even made a further step by acting as prize agents to the officers and men of the ships on their station. If he was astute and entrepreneurial, a purser could make quite a bit on the side by stocking and selling various small items to the officers and men, from crockery to pepper and from warm socks to boot polish. Many would have anticipated a retirement career as a ships’ chandler on shore.

Of those who failed – and judging by the volume of the Victualling Board’s letters to the Admiralty suggesting write-offs of irrecoverable pursers’ debts, there were many of these – some may have had bad luck but many more were the victims of their own incompetence and bad judgement, sometimes with a dash of ill-health thrown in. Samuel Grant was probably typical of this latter sort. The son of a merchant in Aberdeen, he had been purser of various ships, ending up in Pembroke and then Goliath between the late 1790s and 1803; some of his papers have survived and they tell enough of his story to give a picture of the whole. His journals are a mixture of brief personal diary entries and notes of money lent and borrowed. He was not well and mentions this frequently, once remarking that he was a little better and had been able to leave off the flannel from his throat and to prevent catching cold, tyed a lock of my dear Jeannies Hair round my Neck in its stead’. Then he says that the commander-in-chief has written to Admiral Campbell to call him to account for neglect of duty, and adds ‘He may be Damn’d’. After a while, the ship came back to England and Grant went home to his Jeannie, leaving his steward to sort out the remaining stores but it transpires that the steward had been lining his own pocket.

After a sequence of letters to and fro, Grant wrote to the steward accusing him of selling the ship’s stores and embezzling the stocks of candles; the steward returned this letter with a cheeky note scrawled on it, which basically says ‘Hard Luck’ Then there is a statement from Grant’s bankers, Thomas Coutts & Co, and an instruction to them to sell some stocks. A tiny piece of paper, from the constable of the parish where he lived, summoned him to appear and bring details of his income; a copy of the statement prepared for this meeting shows that his income for the year was his net pay of just over £30 and investment income of £65. It is clear that he was in money trouble as well as ill-health. He tried to find someone to take his place on Goliath but failed; he had to go back to sea and his health and spirits suffered again. In the last file, a letter from a friend tells him to buck up and a copy letter from him shows he wrote to the Physician of the Fleet saying that his health was getting worse and begging to go home by the first possible ship. The final, poignant, letter is a formal one from the secretary of the Victualling Board to Grant’s bankers, asking if they want the various documents found in the trunk of ‘the late Samuel Grant, purser of Goliath’.35

Rapacious stewards were not the only vermin to bother pursers. To the modern mind, the idea that ships should be constantly infested with varying levels of rats and insects is horrific, but at that time, although it was possible to control these pests, it was impossible to eradicate them. Wooden ships were full of havens where rodents and assorted insects could hide away and breed and when there had been a major blitz to reduce numbers, others could get on board easily enough. Mice are rarely mentioned. They were, perhaps, less likely to climb the mooring ropes, and there were few stores brought aboard in the forms which usually carry mice, except the occasional fodder and bedding for cattle. Perhaps the rats killed them.

We do not know exactly what sort of rats they were. They could have been the common brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) or the black rat (R. rattus), both of which have the alternate name of ‘ship rat’ It is the latter which brought the bubonic plague to Europe in the fourteenth century. Rats were ever-present on ships and a constant nuisance. They breed at an alarming rate, producing litters of eight or more every couple of months. They gnawed their way into storerooms, bread bags and even casks, and once in they fouled much of what they did not eat. They also damaged other things besides food: sails, clothing and paperwork. Bittern, in the Mediterranean in 1803, has a note in the masters log explaining that a twelve-week gap was due to ‘vermine’ having attacked the rough log ‘being all cut to pieces so as to render it impossible to copy it with any degree of correctness…’. This conjures up a picture of the clerk opening the box or bag and discovering a family of little pink ratlings, all cosy in shredded paper; it also gives an interesting insight into the system of ‘fair’ copying. None of the logs for Bittern cover this missing period and it is common on many ships for all the logs (lieutenants’, masters’ and captains’) to be in the same hand and almost identical wording; some sets have identical doodled enhancement of capital letters. There was no report of what Bittern did about the rats, but the storeship William, when in Malta dockyard, reports ‘smoked the ship with charcoal to kill the rats which had done a great deal of damage to the crew and ships stores’: the next day they found fifty-two dead rats and the following day ‘upwards of 20 dead rats in different parts of the ship’.36

However, rats were not entirely bad news. There are many reports of rats being caught by wily sailors and offered for sale to the hungry (an almost permanent state for the numerous growing boys on board most ships); peppered, salted and grilled, they were declared to be good to eat. They taste rather like rabbit and like all fresh meat, contain small amounts of Vitamin C; the Arctic explorer Elisha Kent Kane who spent one winter trapped in the ice believed that his willingness to eat rats was the reason he was the only one of the crew to avoid scurvy.37 Many people cringe at the idea of eating rat but this is totally irrational; they are considered a delicacy by aboriginal peoples in much of the developing world, as are their close relatives the grey squirrel (Scirius carolinensis) in North America; every nationality (except those whose dietary laws forbid it) eats shrimps, lobsters and crabs, all of which have far nastier habits than rats.

The other ship-borne pest which everyone thinks they know about is the weevil: the cause of biscuits which moved like clockwork was supposed to be black-headed maggots which tasted metallic. This comes from Smollett; he probably got it from Antonio Pigafetta who sailed round the world in 1520 with Magellan; and it was then repeated by Masefield and so on down to the present day, many of the stories embroidered to the extent that it is assumed that all biscuits were like this. Some real accounts of damaged biscuits tell of ‘cockroaches’ having reduced the biscuits to powder, assuming that because ‘cockroaches’ were present, they were the culprits. They were wrong on several counts, as was Pigafetta, Smollett and everyone who has repeated these stories ever since.

The reddish-brown beetle which was taken for a cockroach was actually the Cadelle Beetle (Tenebroides mauritanicus), and its larvae, up to 20mm long, are those black-headed white maggots called bargemen by sailors because they crept out of the biscuits into the bread ‘barge’, the small tub used to hold biscuits on the mess table. These bargemen did not eat the biscuits themselves, but instead ate the minute Bread Beetle (Stegobium paniceum) or its larvae. The Bread Beetle (no bigger than 4mm) is not a weevil either, but a relative of the woodworm. It is the larvae of this creature which eat the biscuit; these are even smaller than the adult (no more than 0.5mm) and since they cover themselves in a mixture of saliva and flour dust, to the naked eye they would be indistinguishable from that dust. This means that no-one would have been aware of their presence in the bread bags; if they had not got onto the bread in the bakeries, they would have done so when they were packed in the reused bags. Weevils, which are a different type of beetle with a very long snout (belonging to the family Curculio) may also have been present in the flour, as there are several varieties which live on grain. These are also very small and would have been almost impossible to see in their larval stage. All of these little brutes lay tiny eggs and all of them breed and mature more quickly in warm, damp conditions. They would have been in or on the bread from the moment it came on the ship, but as long as the bread stayed cool and dry no-one would have noticed, or not until the bread was very old.

This might explain Nelson’s letter to the agent victualler at Malta, ordering more bread to be sent, and remarking ‘I sincerely hope that no weevily bread will be sent, as the Fleet is free from those insects at present…’. This letter was written in November 1803 and despite Nelson’s propensity for exaggeration, may have been true, or as true as the invisibility of the ‘weevils’ allows. If it was not an exaggeration, and given that Nelson had a fleet of over 30 ships under his command, this is an indication that the weevil problem was certainly not as bad as the ‘oh weren’t it awful’ brigade would have us believe. Alas, the situation did not last: between March 1804 and August 1805 ten batches of weevily bread, one of oatmeal, three of flour and five of rice were condemned. But there are no such condemnations before that.38

There are a couple of interesting letters in the Victualling Board papers in 1813, referring to a method of clearing weevils from flour and biscuit which had been suggested to them via the Admiralty. They duly tried it out, and reported, sadly, that it did not work: they had put a live lobster in each of three casks of flour or biscuits, but after three days the lobsters were found to be dead and there was no diminution in the number of weevils; they were even crawling over the bodies of the lobsters. They declined to repeat the experiment, as the workers in the warehouses were complaining about the smell of dead lobsters.39

Other small beetles might have appeared in the pease or dried beans; the author once had the unhappy experience of putting a saucepan of allotment-grown haricot beans to soak in hot water and finding on her return that the water was full of small black beetles. Organically grown and air-dried fruit even today often harbours various tiny insects which proliferate in warm cupboards; these, or other more visible insects were probably the reason that 130 of the 165 messes on Victory refused to accept the raisins in 1798.40

The warmer the environment, the more insects there are. Dillon tells of the occasion when, in the West Indies in 1796, they suffered an invasion of black ants. It is probable that some queens had flown on board and set up their nurseries, as the annoyance lasted several months, with the food covered in ants; and cold pies, when cut, looking more like ink than food. Eventually the ants, Dillon said, grew larger, sprouted wings and disappeared, leaving the way clear for the cockroaches.41 Perhaps he should have been grateful that they had not acquired any bananas complete with stowaway tarantulas.