WE HAVE SEEN THAT THE Georgian seaman’s food was, if not full of variety, at least plentiful and of reasonably good quality. In an age when a sequence of poor harvests might, and in some parts of Europe did, turn the fear of serious food shortages into actuality, those two certainties were not to be sniffed at. Looking at it with modern eyes, people might consider that the official ration was over-heavy in meat and fat but in the short term, given the work those men did, it would have done little harm as it would mostly have been burned off to provide energy and warmth. The problems that might follow from an excess of animal fats do not usually manifest themselves until late middle age and it must be remembered that most seamen were considerably younger than that. The next aspect of the ration which brings a frown to the modern brow is the high salt content; although the salt meat was steeped before cooking, it was probably still very salty. We fear salt-induced strokes, but as with arterial problems, that is an affliction of late middle age. Nobody appears to have kept any statistically-significant records of health problems in late middle-aged ex-seamen, so we cannot know if any of these problems did manifest themselves.

As far as we are concerned here, there are two sorts of health problem: those which were not reported in a form which allows us to identify them as relating to diet and those which were. By 1800 there was a standard printed form for the ships’ surgeons to complete each week and where these forms were not available a hand-written version in the same format was used. A number of these forms have survived, the greatest number of them for the Mediterranean Fleet during the period 1800 to 1805, when the fleet was under the command of first Lord Keith and then Nelson.1 For Keith’s fleet there are forms for individual ships, while for Nelson’s fleet there are consolidated forms prepared by the Physician of the Fleet, one per week, for whichever ships happened to be with the battle squadron at that time. In both cases, the purpose of these forms was obviously to keep the commander-in-chief informed and he, in turn, passed this information back to the Admiralty.

It should be stressed that the available report forms for the Mediterranean are merely those which have survived and also are only those for the ships which were actually in company with the commander-in-chief at the time they were submitted. We do not have a complete set of reports for the whole Mediterranean Fleet, and although there are some returns of numbers in hospital, these are also sporadic, do not necessarily report the specific conditions involved, and do not always distinguish between Royal Navy personnel and prisoners. So we cannot draw any comprehensive conclusions on the level of sickness throughout the station from these reports, but they do give an indication of the prevalence of certain medical conditions and of the numbers of men involved. We do have some commanders-in-chief’s reports for the Channel Fleet for the period 1793 to 1801, and we will come back to these shortly.

The most obvious of the diseases which were not reported as such is alcoholism. Five-sixths of a modern gallon of small beer per day does not do too much harm to a man whose life consists of extremely hard physical work in cold, damp conditions; he burns it off pretty quickly. Nor does a daily five-sixths of a pint of wine do much harm. Indeed, by current thinking, it would counteract the potentially harmful effects of all that fatty meat. Half a pint of very strong rum is another matter: although it would take some time before it irrevocably damaged the liver, it would have kept some men in an almost permanent state of intoxication.

Although there are no actual figures, it was often remarked that many shipboard accidents were caused by rum: falls from the rigging, falls down open hatchways, heavy items being dropped, heads meeting low beams, drunken fights, etc. Keith remarked on it: ‘a large population of the men who are maimed and disabled are reduced to that situation by accidents that happen from [drunkenness]’; and the surgeon Blane pointed out that the incidence of insanity in the Royal Navy was seven times that of the general population (ie one in 1000 as opposed to one in 7000). Blane suggested that this was mostly due to head injuries from drunken accidents.2 Quite a few men were invalided out as insane and there is a suggestion that many of these were in the advanced stages of alcoholism or showing the effects of blows to the head from those low beams. Quite a few officers were invalided out for what, in their case, tended to be called ‘diseased liver’. However, it should be pointed out that as far as the lower-deck men were concerned, since many of them were ‘quota men’ who had been wished on the navy by local authorities who saw this as a way to clear their jails, many could have already been borderline, if not actually, insane from the outset, and this could be what skewed the figures.

The next problem which was rarely reported unless it afflicted a high proportion of a ship’s crew is night blindness. An outbreak was reported in the West Indies squadron in the early 1800s and Gilbert Blane reported having encountered it in soldiers during the siege of Gibraltar in 1779.3 Night blindness is brought about by prolonged deficiency of Vitamin A in the diet – prolonged’ meaning anything up to two years before the stores in the liver of normally-nourished people are diminished. Vitamin A comes in two forms: retinol or beta-carotene. Retinol is found only in animal or fish foods, the greatest amounts in liver and lesser amounts in dairy products and eggs. Beta-carotene is converted in the body to retinol and is found in yellow and green vegetables and some fruits. The deeper the colour, the more beta-carotene, so there is more in the outer leaves of a Savoy cabbage than the inner and even more in watercress, more in carrots than dried peas. The only fruit with appreciable quantities are mangoes, apricots and plums. For full details of amounts of Vitamin A in food, see Appendix 4.

Given that the recommended daily intake of Vitamin A for an adult man is 1000 µg, and that there is very little of it in the standard species of provisions except for butter and cheese, on those foreign stations where neither butter and cheese nor the alternative sources were available, it is likely that it occurred far more than anyone realised. Since night blindness is not a debilitating affliction, it may only have been noticed when lookouts or steersmen in restricted situations| failed to see something at night or in other dim light. This is the most likely reason for so few reports, not, as has been asserted, because of the general introduction of portable soup. There are two problems with this assertion: the first is that portable soup was only given to the sick; the second is that it does not contain any Vitamin A. The belief that it does contain Vitamin A arises from the statement that portable soup was made with offal, the erroneous assumption here being that ‘offal’ in 1756, when Mrs Dubois started making portable soup for the Sick and Hurt Board in London, meant what it does now and thus would include the retinol-rich liver and kidneys.

Alas, the secondary source which reported the use of offal failed to read on down the original document, which defines offal as ‘legs and shins’ of beef, then adds that one-third of the meat could be mutton.4 The following year, the appropriately-named Mrs Cookworthy was contracted to make portable soup at Plymouth, both she and Mrs Dubois using meat provided by the Victualling Board slaughterhouses. By 1804, a letter confirms that the only meat used since 1756 was leg and shin of beef with one-quarter of mutton. Shin of beef contains quite a lot of gelatinous connective tissue and it is this which makes the broth set like jelly, not the addition of calves feet suggested by yet another misguided modern writer. Anyone who is in the habit of cooking from basic ingredients will be aware of this property of shin of beef and will also know that liver and kidneys do not produce that result when boiled. Indeed, it was that knowledge which made the author, deeply sceptical, seek out the original documents, one of which fortuitously included the recipe. This showed that the meat was simmered for several hours, then drained and pressed to extract all the stock, which was then seasoned with celery seed, black pepper, garlic and essence of thyme. The end product, after reduction and drying, was a cake of solid jelly (stamped, of course, with the King’s broad arrow mark), one ounce of which would make one quart of soup when dissolved in boiling water.5 Contrary to some modern comments, this soup bears no resemblance to glue; it is extremely tasty (see Appendix 6 for the recipe).

Before moving on to the main dietary deficiency disease of sailors, scurvy, it is worth remarking that, while there are other vitamin deficiency diseases, we have no evidence that they afflicted sailors on a grand scale, which is not to suggest that they did not, merely that they were not reported in a form which makes them recognisable as such.

Scurvy was something you could not miss. It has easily recognisable symptoms: bruising and ulceration of the skin, haemorrhaging and joint pains, loosening of the teeth, loss of hair, opening-up of old wounds, lassitude and depression, hallucinations and blindness, and finally death. Now we know that it is due to a deficiency of Vitamin C which leads to the breakdown of the body’s production of the connective tissue collagen; then all they knew was that it was a disease which wreaked havoc among sailors on long voyages.

Scurvy was reported in two forms: scurvy and ulcers. Sometimes there was a separate entry on the forms for ‘scorbutic ulcers’; but it is probable that almost all, if not all, of these were of scorbutic origin, persistently ulcerated skin being one of the common symptoms of scurvy.6 They would not have been peptic ulcers, as these were not identified until 1857;7 this is not to say that seamen did not suffer from such ulcers, but that these would have been listed under different headings.8 The ulcers reported would probably have been mainly on the lower legs and feet; Dr Snipe, the Physician of the Mediterranean Fleet, remarked on the high incidence of such ulcerated scratches and condemned the practice of going barefoot as the cause.9

The earliest record of scurvy is from Vasco da Gama’s voyage to India in 1497, when he lost 100 of his 160 men; there have been many since. Perhaps the best known to British naval historians is Anson’s circumnavigation in 1740. Of the more than 1900 men who sailed with Anson, some 1400 died, and although some died of dysentery and the crew of the Wager of starvation, it is thought that the majority died of scurvy, many possibly because they were already weakened from having been confined to their ships at Spithead during a series of Admiralty-induced delays.10 Despite the good effects of citrus fruit having been known as an antiscorbutic since at least 1600, when the East India Company surgeon John Wooddall recommended it, the Anson expedition carried no citrus or other antiscorbutics.

It was the reports of this expedition which inspired the young Scottish naval surgeon James Lind to seek an effective cure for scurvy. He was not the first to think that scurvy could be cured by diet supplements, but he was the first to set about finding a cure by conducting logical experiments. This was, of itself, somewhat of a novelty at the time; previous attempts to find a cure having been on a rather hit-or-miss basis. It is when you consider some of the theories on the causes of scurvy and the ‘obvious’ cures that you begin to see the gulf between Georgian and modern medical theory.

The first thought, because some of the symptoms were similar, was that scurvy was a venereal disease. After all, sailors were known to be promiscuous and since no-one thought to question the sufferers on the matter and collate the answers, it was never disproved. Another theory, based on the doctrine of four humours, was that scurvy was a corruption of the blood, leading to putrefaction. This demonstrates another great gulf between modern and ancient medical thinking; now, when disease occurs on a grand scale, we believe it must have a specific cause rather than being a generalised imbalance of the whole body. The doctrine of four humours was originally promulgated around 400 BC by Hippocrates, who believed that the four humours were the principle seats of disease. Galen, some 500 years later, taught that as well as the four humours, there were four qualities, four elements and four complexions, all inter-related. His theory was that good health came from a good blend of all these; that specific diseases were linked to an excess or deficit of some, and that different foods had different qualities in different degrees. So, if you were suffering from an affliction which was hot and moist, you needed food or medicine which was cool and dry, and depending on the degree of the affliction, so you needed a balancing degree of the appropriate curative. At this point, a cynic might observe that such a complex doctrine could only be understood by a learned man, and that such a man would charge a large fee for his hard-learned knowledge and would also defend it vigorously against any alternative theories.

The ‘putrefaction’ theory, expanded upon by Sir John Pringle in a paper read at the Royal Society in 1750, was that disease came about from putrefaction which was best treated by alkalis. David MacBride took Pringle’s theories a little further, deciding that carbon monoxide, which he called ‘free air’ and which came from fermentation, would prevent putrefaction. He proposed a cure based on the fermentative quality of fresh vegetables and malt. Lind also subscribed to the putrefaction theory but felt that both alkalis and acids were needed; he recommended oranges and lemons for their acid qualities.

Lind’s experiment, carried out in 1747, consisted of dividing twelve sailors with scurvy into six groups, treating each with a different remedy. Their main diet was identical for all: fresh mutton broth, puddings (undefined), boiled biscuit with sugar, barley, raisins or currants, rice, sago and wine. Group one were given a quart of cider each day, group two had twenty-five drops of elixir of vitriol, group three had six spoonsful of vinegar, group four had half a pint of seawater, group five had two oranges and one lemon each day and group six had a paste made of garlic, mustard seed, horseradish, Balsam of Peru and gum myrrh and a drink of barley water acidulated with tamarinds and cream of tartar. Group five were reported as eating their fruit with greediness, and despite the treatment stopping after six days when Lind ran out of fruit, one of those men was by that time fit for duty and the other was well enough to help in nursing the others. Group one showed some recovery after two weeks, and the others showed no effect.

Shortly after conducting this experiment, Lind left the navy to concentrate on his doctoral thesis. This was not on scurvy but on an aspect of venereal disease; however, it won him his degree and licence to practice as a physician, first privately and then at Haslar naval hospital at Portsmouth. In 1753 he published his Treatise of the Scurvy; it was virtually ignored. There were louder voices crying their own theories, one of these being MacBride whose answer to the problem was wort, the thick concentrated form of beer produced by long simmering. This was one of the ideas originally tried as an answer to running out of beer at sea, the theory being that if mixed with water (one part wort, twelve parts water) it would quickly turn into beer. It actually did do this, but having got the reputation of being a medicine, this beer was rejected by the men.

Cook carried wort on his first voyage and reported on his return that he found it an effective antiscorbutic, but then contradicted himself by remarking that ‘we have been a long time without any, without feeling the want of it…’. This statement was omitted when the report was presented at the Royal Society in Cook’s absence. Cook also carried, and made his men eat, sauerkraut which is mildly antiscorbutic, as well as syrup of oranges and lemons, and went ashore for fresh food whenever he could. These latter aspects were also ignored. MacBride published two reports on sea trials of wort: these were, however, flawed, one having been carried out by his brother, the other involving a voyage which included a stay of several days on an island where the scorbutic men soon recovered.11

Meanwhile, various voices were crying about the effectiveness of fresh food and others about lemon juice. The fresh food believers tended to be those who thought scurvy was caused by salt; they thought it was fresh meat which principally effected the cure. At first only a few realised that the fresh vegetables which traditionally accompanied fresh meat had anything to do with the cure, but the idea that fresh vegetables were helpful gradually came to be accepted. There is, incidentally, a little Vitamin C in fresh meat, but only if you eat it soon after slaughter; when the meat is hung, the Vitamin C is gradually lost. This was the reason rats were an effective antiscorbutic: they were eaten soon after being killed. Nelson was of the ‘fresh meat and vegetables’ persuasion and he placed much faith in onions, arranging for them to be bought in large quantities whenever possible. Onions are anti-scorbutic, 100g of raw onions containing the minimum daily dose of 10mg of Vitamin C. Another of the prominent naval doctors of the time, Thomas Trotter, was also a fan of fresh vegetables. When serving as Physician to the Channel Fleet in 1795, he insisted on fresh vegetables for the fleet, going round the growers and markets to such effect that one greengrocer complained that Trotter had ruined his business by sending all the salad to Spithead.12

Lind, in his essay on preserving the health of seamen, recommended that ships’ companies should grow their own salad (cress) on wet cloths and to put out blankets in rainy weather to soak them before sowing the seeds, so that ‘the whole ship both above and below shall be replete with verdure’.13 In 1775, Messrs Mure, Son & Atkinson, the contractors supplying the British army in America in the winter of 1775, sent out a supply of mustard and cress seeds, suggesting that they could be grown on wet blankets or shallow trays of earth.14 Pasley had such trays with him on board Jupiter in 1781 and his could not have been shallow, as when some of his scurvy sufferers asked to be covered in earth to alleviate their sufferings, he said he buried them in the trays, so these must have been at least 12 inches deep. This odd treatment seemed to work, although its effect can only have been psychotherapeutic: ‘the men who were carried and lifted in and out of it, incapable of moving a limb, walked of themselves today.’15 Pasley’s salad trays seem to have been for his own use, rather than intended for the crew, but in 1803 a letter to the Naval Chronicle from Sir W Young, who had lived in India for several years, recommended sprouting peas to provide a ‘living vegetable’. His method reads exactly like the modern method for sprouting mung beans (as used in Chinese cooking): take some small tubs of about two-gallon capacity, three-quarter fill them with pease, add water to just cover and leave them to sprout. He suggests feeding them to the men twice a week, ideally raw.16

Lind, Trotter, Nelson and his surgeon Leonard Gillespie also advocated citrus fruit. Others were only semi-convinced that the fruit itself or its juice were necessary. Citrus fruit is acidic, they reasoned, the curative property was acid, so it would work just as well if they used cheaper acids, such as vinegar or ‘oil of vitriol’ (sulphuric acid!). The high cost of citrus fruit (or the sugar required to make it palatable) is a recurring theme in the ongoing history of treating or preventing scurvy. It is interesting to note that the French navy’s answer to scurvy, sorrel (Rumex acetosa), also tastes acidic.

The person who had turned the tide in favour of citrus juice is generally believed to have been Dr Gilbert Blane, who had been personal physician to Sir George Rodney and Physician to the Fleet before he became one of the Commissioners for Sick and Wounded Seamen (commonly known as the ‘Sick and Hurt Board’). Blane was a strong believer in citrus juice, but dubious of the efficacy of the ‘rob’ (syrup) which Lind had advocated, believing – correctly as it happens – that heat impaired the properties of the juice; however, it seems that although he publicised the idea, he was not responsible for the Sick and Hurt Board’s enthusiasm, which came from an experiment conducted just before he joined the Board.17 In 1794 an experiment was made using fresh lemon juice on Suffolk, on a non-stop twenty-three week voyage to India. Two-thirds of an ounce of lemon juice with two ounces of sugar was mixed with grog and given to every man in the ship. Only fifteen showed signs of scurvy, which disappeared when the lemon juice ration was increased. The dosage of two-thirds of an ounce of lemon juice gives just short of the modern recommended minimum daily allowance of Vitamin C. It should be mentioned, however, that the requirement for such things is not absolute; requirements differ between individuals. It is interesting to note when studying ships’ sick returns that even on ships where there is not a serious outbreak of scurvy, there are always one or two cases each week. There are various possible reasons for this: perhaps these men were debilitated when they joined the ship, perhaps they did not like the taste of lemon juice and did not drink their ration, or perhaps they were heavy smokers or tobacco-chewers and thus needed more than the usual amount of Vitamin C.

The successful experiment on Suffolk, together with Blane’s influence as a member of the Sick and Hurt Board, persuaded the Admiralty to arrange for an issue of lemon juice in the following year. This tends to be lauded as the end of scurvy in the navy. It might have been, if it was a regular, general issue to every man on every ship, but that is not what happened. In 1795, the Admiralty had agreed to send a supply of lemon juice and sugar to the two squadrons blockading Brest and Quiberon Bay, to be issued ‘at the discretion of the ship’s surgeon’.

This phrase ‘at the discretion of the ship’s surgeon’, together with the influence of the Physician of the Channel Fleet, Trotter, meant that the lemon juice was not used as it should have been. The problem with Trotter was that while he advocated citrus juice as a cure for scurvy, he was very much against using it as a preventive. He believed that daily doses of lemon juice weakened the constitution. When St Vincent succeeded to the command of the Channel Fleet in 1800, having seen the efficacy of lemon juice in his previous command in the Mediterranean, he almost immediately clashed with Trotter on this, and other, health matters, and within a few weeks Trotter was ousted and replaced by Dr Andrew Baird, who did agree with St Vincent.18 This led to supplies of lemon juice eventually being issued to all ships of the Channel Fleet and this, together with regular supplies of fresh vegetables and fruit, allowed the blockading ships to remain on station for longer periods.

By 1803, when Nelson took over the Mediterranean Fleet, most ships going on foreign service carried a supply of lemon juice, again to be issued ‘at the discretion of the ship’s surgeon’; it was not included in the list of standard rations or as a substitute for fresh food. This was because it was still regarded as a medicine and thus under the control of the Sick and Hurt Board, not the Victualling Board. In 1806, when a new edition of the Regulations was issued, the single mention of serving out lemon juice was in the chapters for surgeons, where it states that on long voyages, if there is insufficient lemon juice for the whole ship’s company, they are to give the captain a list of those men most in need. The instructions for the Physician of the Fleet say ‘he is to point out to the commander-in-chief whatever he may think necessary for the recovery of the health of the crew of a ship particularly sickly, or for the preservation of the health of the fleet in general’. Even as late as 1825, the Instructions to Pursers state that lemon juice is not to be issued while the ship’s company are ‘making use of beer, or are furnished with fresh beef, or enjoying a supply of fruit or vegetables; nor during the space of a fortnight after the issue of [the above listed items] unless for the state of health of the crew, the surgeon should think the same necessary.…’19

The responsibility for dispensing lemon juice was divided. The Sick and Hurt Board wanted to keep control, but also wanted the Victualling Board to store and issue it. At the point at which it was agreed that it should be issued to all ships on foreign service or blockade duty, the Sick and Hurt Board wrote to the Admiralty to inform them that they were ready to start delivering packed lemon juice to the Victualling Board stores and asking for the Victualling Board to provide a list of ships it went to, so they could send instructions to the surgeons on how to use it. This request was passed on to the Victualling Board who promptly pointed out that it would be more sensible if they were given a supply of the instructions to deliver with the lemon juice, as otherwise ships might have sailed before the instructions reached them.20

This shuffling of responsibilities continued: in 1806 the Sick and Hurt Board was put under the control of the Transport Board (and in 1816 became a department of the Victualling Board). In 1812 the Transport Board suggested that as lemon juice had ‘now become a class of victualling of the first necessity’, the Victualling Board should take on its provision ‘in the same manner as other articles of provisions, furnishing such quantities thereof as the Transport Board … require for the use of the sick’. The Victualling Board did not want to do this and replied that they did not agree that lemon juice fell under the denomination of a ‘regular article of diet’. Its use had been introduced by the medical department and they felt that the responsibility for it should stay there, adding rather waspishly that it was difficult enough to find enough space for ‘indispensable articles of the first necessity’ let alone anything else.21 However, it seems they were obliged to take on this task, for in 1813 they were complaining about the cost of the sugar that was traditionally served with lemon juice, and managed to persuade the Admiralty that they should revert to serving it only as a cure, not a preventative.22

When the decision was made to supply lemon juice (and they did refer to it as juice, not rob) on a grand scale, in 1796, it was packed in cylindrical bottles in sectioned cases, each case containing eighteen half-gallon bottles. Earlier bottles had been much larger, some containing as much as eight and a half gallons.23 It had originally been proposed that the bottles should be square, but these were found to break more easily than the round ones.24 There had been some experimentation with the preparation of the juice, and it was finally decided that owing to the risk of adulteration at source if bought ready-squeezed, the lemons should be squeezed in Britain. There was some discussion about the extra cost of importing whole fruits but the conclusion was that the difference in freight cost between lemon juice and whole lemons was about the same as it would have cost to set up a reliable squeezing operation abroad and that they would prefer to have this done ‘under the eye of the board’. One wonders what they did with the peels: were they just thrown away, or did some enterprising person see their possibilities for making lemon marmalade or drying them for lemon ‘pepper’? By 1804, when Nelson’s Physician of the Fleet, Dr Snipe, went to Sicily to supervise the Board’s contract for lemons, the situation seemed to have changed, as he ordered juice rather than lemons: a total of 50,000 gallons, at least 10,000 gallons of which went to Nelson’s fleet while the rest went back to England.25

What about actual scurvy cases? During the early stages of the Brest blockade, before fresh vegetables and lemon juice were provided, the commander-in-chief, Lord Bridport, sent back two reports of numbers of sick: on 16 August 1795 this consisted of some 475 cases in thirteen ships, most of these scorbutic, but during September this figure had risen to 861 cases in ten ships. While lemon juice was only used as a cure not a preventive, the situation changed little, but when St Vincent took command in 1801 there was a significant difference; we do not have specific figures on scurvy, but we do have those for numbers of sick men at Haslar hospital at Portsmouth: 15,141 in 1779, 1667 in 1804.26 For the Mediterranean Fleet which he had previously commanded, and where he had used lemon juice as an antiscorbutic, the picture was very different. The number of cases reported on the available forms for 1800 to 1805 rarely reached even double figures – this in squadrons totalling between 3000 and 7000 (Keith’s) or 4500 and 6000 men (Nelson’s) – except on the occasions when there was an outbreak on specific ships. The figures for ulcers, although still representing only about 0.5 per cent of the men, is higher, running between 35 and 50 cases each week. Overall the level of sickness in these squadrons, judging by the returns which have survived, was very low, running at a level which rarely exceeded 5 per cent of the numbers borne.27

Nelson commented on various occasions on the remarkable healthiness of his fleet.28 We do not know how he was judging this, other than the figures reported by the Physician of the Fleet, or what he was using as a comparison; if it was the recent experience of a similar squadrons in a similar location (Keith’s), as we have seen above there is little difference between them. It may have been his experience of serving in the West Indies in the 1780s, when yellow fever and other tropical diseases cut a swathe through British sailors.29 Alternatively it may have been his experience at Corsica in 1794 when he reported ‘we have upwards of one thousand sick out of two thousand, and the others not much better than so many phantoms’; at one point, the crew of Agamemnon became so weak that they were unable to raise the anchor and had to buoy it and cut the cable.30

In this context of remarkable health and scurvy cases it is interesting to study the logs of a couple of Nelson’s ships in the Mediterranean, Triumph and Gibraltar. Between January and May 1803 Triumph was at Malta, where she took on considerable quantities of provisions; by the middle of June she had joined the main battle squadron off Toulon. Apart from a two-week period at the end of July when she was in Gibraltar having her bowsprit replaced and waiting for a convoy of transports, she remained with the group off Toulon during the next year. When she had been at Gibraltar she received daily supplies of fresh beef and substantial quantities of other provisions; off Toulon she received occasional small amounts of various items from other ships in the squadron, but otherwise, with the exception of live sheep and bullocks whilst at the Maddalena Islands, all her provisions were the basic ration items and these came from transports, either at sea or whilst moored at Palma Bay or the Maddalena Islands.

Her master’s log gives frequent details of provisions received and it is noticeable that she reports receiving only three amounts of onions (fourteen bags on 19 December 1803, three bags on 16 March and 1000 pounds on 22 March 1804) and no citrus fruit or juice after September 1803. From this it appears that the only Vitamin C available after July 1803 was the small amount present in fresh meat and those few onions. Hardly surprisingly, by May 1804 she had thirty-seven men with scurvy; her captain reported this to Nelson, who ordered a special issue of lemon juice. It is possible that she had none on board, as during the course of the following month she received eight casks of lemons from Royal Sovereign, and a total of eleven cases of lime juice from transports.31

Gibraltar had been in the Mediterranean for some time when Nelson arrived in July 1803, and by this time she was an unhealthy ship. At the end of March 1803 she had discharged twenty-one sick men into a transport, and between then and the beginning of May she had sent eleven men to hospital, one of them the surgeon. Between 28 June and 21 July three men died on board the ship; no reason is given for their deaths, or for sending the other men to hospital, but one can speculate that the reason for at least some of this sickness was scurvy, as on 6 August she moored at the Maddalena Islands, built a tented hospital and sent 135 scurvy cases on shore. She remained there for ten days, where she reports receiving sixty-four bullocks (and killing eighteen of them) and 16,700 onions, 101 pumpkins and 100 pounds of grapes ‘for the sick’. One man died in the hospital, but by 16 August the rest were back on board and they went back to rejoin the squadron with the commander-in-chief. She was then sent to Naples, arriving on 20 September, and there she stayed for the next eight months, apart from making a two-week round trip to Sardinia to collect the Duke of Genevois and his retinue. While she was at Naples, she received deliveries on most days of fresh beef, cabbages, pumpkins and onions or leeks, as well as other provisions and wine. During the whole of her time at Naples she reported no further deaths or outbreaks of scurvy.32

Even more telling is the fact that there were several serious outbreaks of scurvy in the fleet during 1803 and 1804 and several more after Spain declared war against Britain in December 1804, thereby cutting off a major source of fresh food.33 There would have been no difficulty in obtaining a plentiful supply of lemon juice for the fleet, as lemons were grown extensively in Sicily; Nelson was fully aware of this, having sent his physician, Dr Snipe, to buy large stocks of lemons both for his own fleet and to send back to England. The fact that scurvy continued to be a problem indicates that this supply was not fully utilised.

This demonstrates that the general thinking of many modern writers that everyone, from the Board of Admiralty all the way down to individual ships’ captains and surgeons, was convinced that citrus fruit or its juice was a sure preventative of scurvy is incorrect; if they were convinced, captains and surgeons would not have needed to be told to buy lemons or issue the juice. There is other evidence of this lack of conviction: as commander-in-chief, Nelson could have issued a general order on the subject of issuing lemon juice, but his order book does not include such an order; only one on the format in which the remaining stocks of lemon juice should be reported.34 In addition, the large batch of ships’ logs which were examined during the author’s research did not show regular receipts of lemon juice or lemons in the quantities which would have been required for a standard regular issue.

This fleet in the Mediterranean was not the only one which continued to suffer from scurvy. In 1811 the commander-in-chief of the East India station, Rear-Admiral William Drury wrote of the ‘ravages of scurvy and dysentery’ in his fleet. It was probably the dysentery which caused, or at any rate worsened, the scurvy: dysentery raises the pH of the contents of the gut and in the process destroys the ascorbic acid. In a vicious circle, sailors with lowered resistance due to scurvy were also easy victims to dysentery. The term dysentery does not appear frequently in the ships’ medical reports; ‘flux’ does and whether this flux was full-blown amoebic dysentery or just diarrhoea caused by bad water or failure to wash food or hands, the effect would be much the same. Drury found it difficult to obtain lemons or limes, although one wonders why supplies could not have been taken out to him by the East India Company ships. Equally, it is strange that he did not know about the coconut, which should have been easily available on the East Indies station; it had been known as early as 1766, when Commodore John Byron reported using it on his circumnavigation. Although comparatively low in Vitamin C, at 2mg per 100g of the fresh flesh or milk, if sufficient was available it would have done the trick.

However, Drury did know of another good cure: nopal (Opuntia) was believed on the East Indies station to be the best remedy for scurvy and hepatitis. Its alternative name at the time was ‘Mexican cochineal plant’, from the cochineal beetle which lives on it (Dactylopius cocchus), but we know it as the Prickly Pear. The varieties we know today are very spiny; however, there is a spineless variety (O. ficus-indica) which may have been what was available there. Alternatively, they may have used a variation of the technique used today in Mexico where the spines are burned off with a blow-torch; Georgian sailors could have used the ‘bundle of brushwood on a stick’ method to singe the spines before handling them. The recommended dose was ‘one leaf per man per day’in the soup, or a pickled version which could be made on board. Nopal’s properties were discovered by the Physician General to the Madras army, Dr Anderson, who got his first plant sent out from Kew Gardens by the good offices of Sir Joseph Banks.35 He reported to Banks in 1808 that several East India Company ships were using it to good effect; unfortunately it is not one of the items listed in the standard works on food composition so we cannot know its vitamin levels.

Drury was a believer in nopal and grew large amounts in his garden at Madras, offering as much as was wanted to any ship’s captain who cared to come and fetch it. He recommended its use in a pickle, with vinegar and various spices, including allspice. Even here, someone had to interfere and change the recipe on the grounds of cost. Drury had died and his pickle recipe was altered by the resident naval commissioner, Peter Puget, who decided because the price was too high, to omit the allspice. As it happens, it did not matter but how could he have known that? If they were prepared to accept that the bark of the cinchona tree could have such a valuable effect on fevers, why should the seed of allspice not have been effective with scurvy? But no, a few pennies were more important, as they were deemed to be later when limes were substituted for lemons. In fact, this view of the cheapness of limes proved to be faulty; they turned out to be more costly and less effective than lemons. It was not until the 1930s, when Casimir Funk and a sequence of other chemists identified the four main dietary deficiency diseases (scurvy, beriberi, pellagra and rickets) as such and went on to isolate and then commercially produce Vitamin C that there was a cheap and effective antiscorbutic available for those whose diet denied them the Vitamin C they needed.

So much for the food that might have prevented sickness. When they went on the sick list and were moved to the sickbay or to a hospital, the responsibility for feeding the men shifted to the surgeon. He decided whether they should be on full, half or low diet, liaised with the purser on how much of their official ration they should have, and with the captain when the need for mutton broth required a sheep to be killed, or when the sick needed wine at a time when the rest of the crew was on beer or spirits.

The general theory was that their consumption of ‘salt provisions’ should be, if not completely stopped, restricted to what was needed to make gruel or ‘sowins’, which is a type of very thin oatmeal porridge. The dictionary definition (which also offers the alternative spellings of sowens or sowans) suggests this was traditionally made with the floury residue left in the husks of oats after crushing, conjuring up the picture of extreme desperation, washing the inedible husks for what little nutriment they could yield. Another name for this dish was flummery, originally sweetened and with milk added, it gradually developed through the eighteenth century to a rich dessert with cream and Madeira, and eventually fruit. Hannah Glasse offers a ‘French Flummery’ with cream, rose water and orange-flower water; fit for the Admiral’s table perhaps, but too rich for the sick bay. Since there would have been no oat husks on board, the sowins would have been made with the oatmeal that was part of the sick men’s usual ration. The Regulations go on to say that the men’s allowance of flour should be used to make soft bread or puddings and that ‘these, together with their molasses or sugar, when allowed, and raisins, the necessaries in [the surgeon’s] charge, and portable soup, will constitute a wholesome diet for the sick’.

The surgeons’ ‘necessaries’ were provided ready-packed in boxes. There seem to have been three sizes of box: half-single for 25 men, single for 50 men and double for 100 men, each meant to be sufficient for three months. In each case, the amount of contents doubled up as did the number of men they were meant for; although it does not specifically say so in the Regulations, this must have meant the number of men in the complement, not those in the sick bay, so Victory, with her 850 men, would have eight double and one single box for each three months of her expected service. The double box contained, as well as linen and flannel, one saucepan, one canister each for tea and sago, 4½ pounds of tea, 4 pounds of sago, 8 pounds of rice, 16 pounds of barley, 32 pounds of soft sugar and 2 ounces of ginger (presumably this would have been the powdered sort), except in the Mediterranean where the barley was replaced by macaroni, and in the West Indies where it was replaced by arrowroot. Replacements of items used were provided by the local officer of the Sick and Hurt Board on production of certificates of what had been legitimately used; on stations where there was no such officer, the surgeon could purchase these necessaries to the tune of twopence per man per month. Portable soup and lemon juice were dealt with on a much longer list of drugs and equipment for the sickbay, including pillows, night caps, bed-pans and spitting pots.36

The list of dietary necessaries had changed over the years. The version quoted above was that for 1806; earlier versions had included cocoa or chocolate, garlic, shallots, almonds, tamarinds and the spices nutmeg and mace. Toward the end of the Napoleonic Wars, after the development of canning, tins of ‘preserved’ veal and soup joined the list. In naval hospitals on shore, milk, sometimes eggs, vegetables and, after about 1805, potatoes joined the list. Milk also featured on the diet on hospital ships; they must have carried goats or even milch cows. Goats were quite common on all ships, and although they usually belonged to the officers, it is unlikely that their milk would have been denied the sick. It was also common practice for delicacies from the officers’ tables to be sent to the sickbay.

With the exception of these goodies from the wardroom, the general trend of the diet for the sick seems to have been soft and non-challenging food, rather like the diet in Victorian schoolrooms, with the addition of those spices to add some flavour. Men on full diet, probably those in the latter stages of recovery, did get some meat; the others only got meat broth or soup, with those soft puddings or gruels. To men used to large amounts of solid food, this diet would not have encouraged malingering. But, in northern Sardinia at least, there were those grapes, possibly a forerunner of that classic gift of hospital visitors.

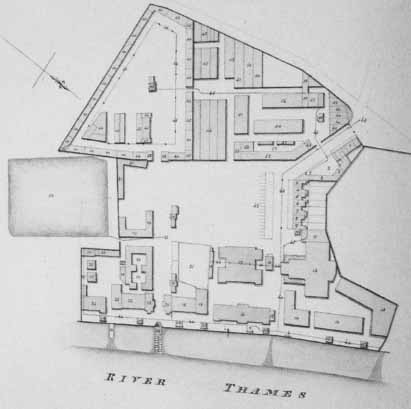

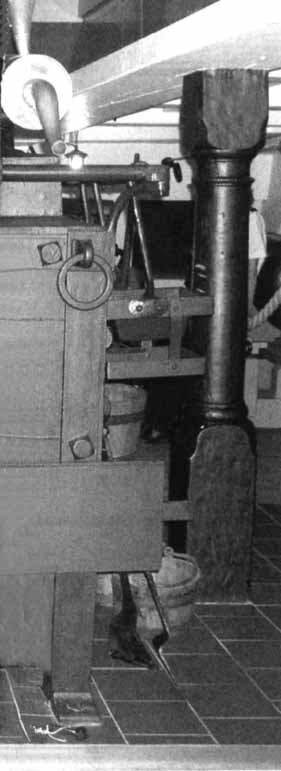

Method of suspending a small barrel. This is how the officers’ beer or wine would be kept in the wardroom, with a tap fitted to facilitate pouring.

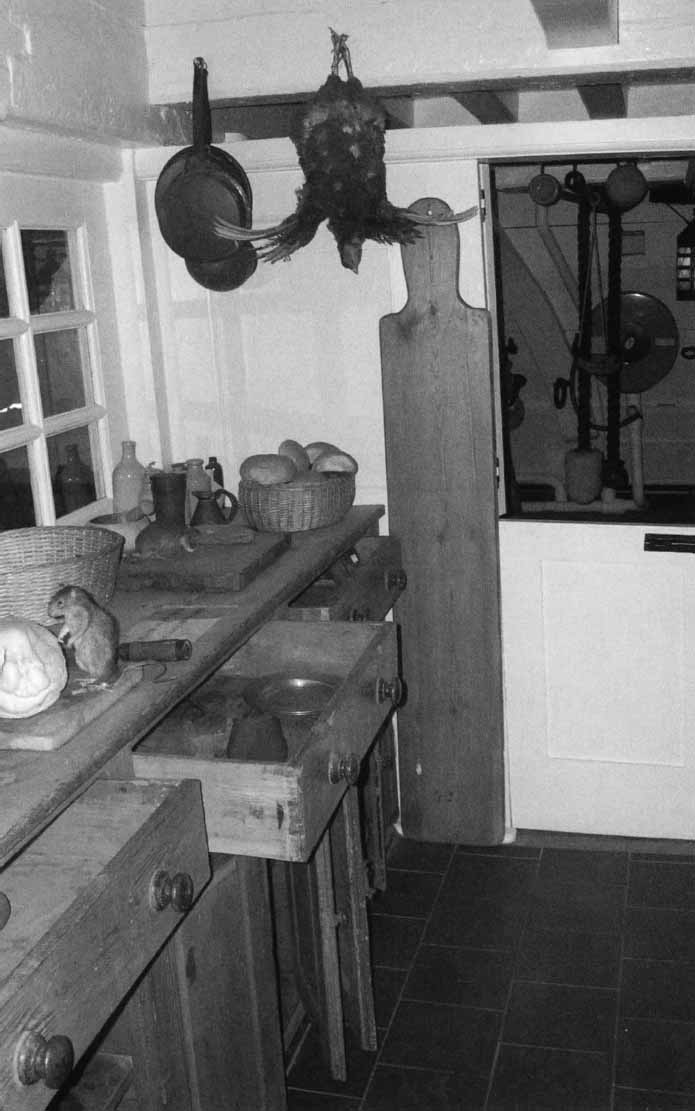

Plan of the victualling yard at Deptford as it was in 1813. The size of the establishment can be gauged by some of the statistics quoted in the key: the slaughter house could accommodate up to 260 oxen, and the hog hanging house 650 pigs; the bakehouse had twelve ovens; and the spirit vats held 56,000 gallons. Besides the large storehouses, there were ranges of houses for the yard officers and craftsmen. (PRO Adm 7/593)

A mess table on the Victory. Note the square plates, cow’s horn drinking mugs and ‘half-barrel’ mess kids. The hammocks would not normally be slung during mealtimes. (Photographs of HMS Victory by kind permission of the Commanding Officer)

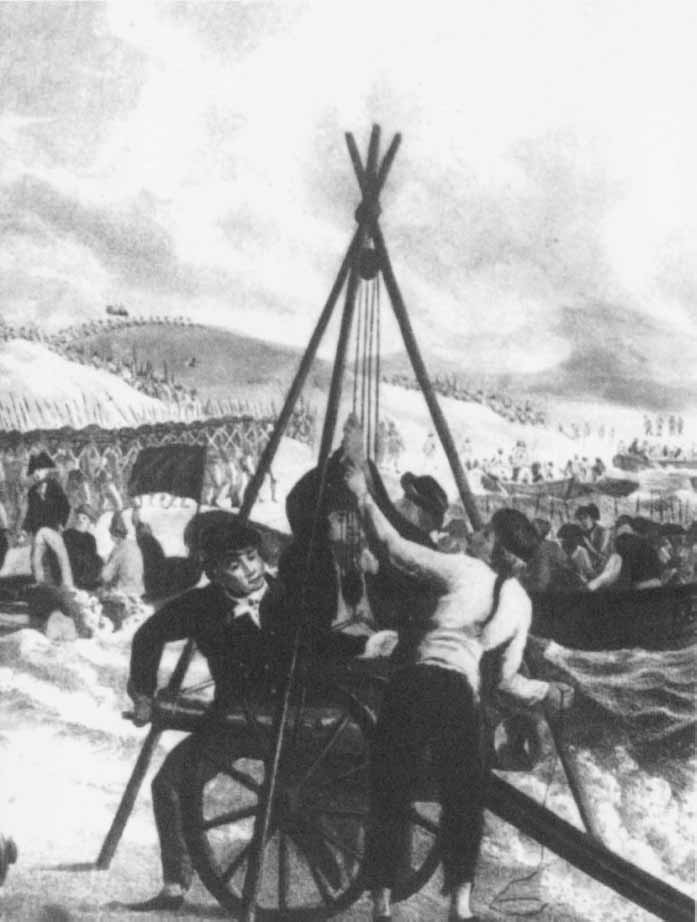

Detail from a contemporary print, showing the use of a ‘triangle’ to lift a heavy object – here a gun, but it was also used to lift barrels from beach to boat.

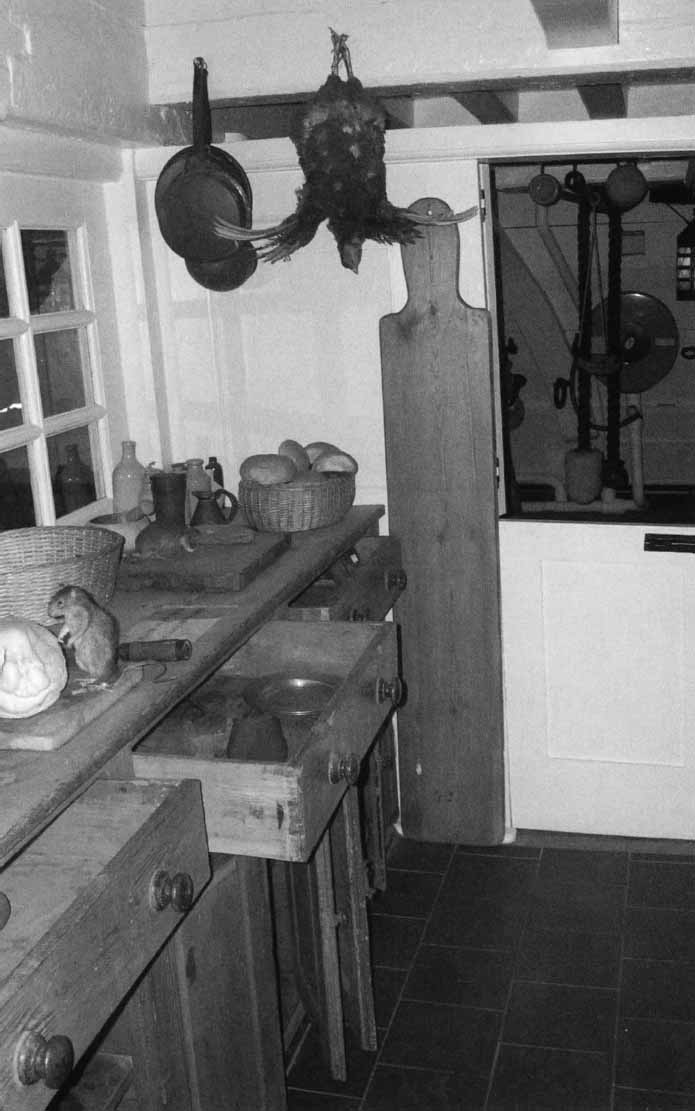

The preparation area in the galley on the Victory. The long wooden object next to the half-door is a peel for moving bread and dishes in and out of the oven. Note the ever-present rats.

Side view of the replica Brodie stove on the Victory. Note the buckets and the chain for driving the spit. This was operated by a smoke-jack in the chimney. The square open container is a salt box, which housed two ready-use powder cartridges, so was presumably only kept in this position when the ship was in action (when the stove would be doused).

Another view of the replica Brodie stove on the Victory. Note the condenser (top left), the large tubs for steeping salt meat and receiving liquids from the boilers, and the cocks (bottom left) for pouring these off.

The open fire at the front end of the Brodie stove on the Victory. Note the different facilities for standing or hanging cooking pots and kettles.

Side view of the replica Brodie stove on the Victory. From top right, clockwise, note the lids of the coppers and their extreme proximity to the beams above, the hanging stoves on the rail, the open fire-box (this is underneath the coppers), the closed door to the oven and the supports on which the spit would be mounted.

Casks stowed in the hold of the Victory, with the bottom tier nestling in shingle ballast.

Cheese racks in the purser’s steward’s room on the Victory.

A close-up of the preparation area in the galley on the Victory. Note the stoneware bottles and the wooden pestle and mortar for grinding spices.