A Brief History of Libraries—or, How Did We Get Here?

And further, by these, my son, be admonished: of making many books there is no end; and much study is a weariness of the flesh.

—Ecclesiastes 12:12

On the Binding Properties of Libraries—Keeping the Forces of Entropy and Disorder at Bay

The ancient Greeks had an “app for that,” or at least a story. From Pandora to Prometheus the heroes in their myths have trouble with powerful inventions—by misusing them, stealing them from peevish gods, or failing to grasp their future ramifications. Theseus, for example, trapped in the Minotaur’s maze, escaped only by following a length string that Ariadne had secretly given him. That slender string kept Theseus linked to the outside world as he penetrated deeper into Daedalus’s labyrinth and into the Minotaur’s lair. Even though Theseus was eventually forced to abandon Ariadne on the island of Naxos and inadvertently drove his father to suicide, he was the lucky one. Everyone else who took on the maze and the Minotaur died in the process. We all know what happened to Daedalus’s son, too, when the father-son duo fled the half-crazed kingdom of Minos on wings made of wax and feathers (Nowadays some precocious programmer might call this “i-carus,” the app that guarantees digital filial obedience.)

In some ways the myth of Theseus mirrors the contemporary Internet user experience. The myth suggests that any system—be it physical, psychological, or informational—that confounds its users becomes a dangerous one. Losing the connection with the real world in the twists and turns of life is an experience akin to death. What is at stake in the current incarnation of the web is the basis of knowledgeable existence itself. When one can no longer draw the thread between pieces of verifiable information, meaning gets lost, and that loss of meaning contributes to the death of knowledge and the ultimate decline of a culture. Think “digital Dark Ages,” but not as a loss of access to information—as an undifferentiated glut of bits and bytes jumbled together and reconstituted at will by unseen and unknown forces whose motives are not discernible.

Libraries have made the attempt for centuries to ensure that the strings binding information together remain intact. In the past, this was easier, as the amount of published and archival work was much lower and therefore more manageable. Binding books; creating physical spaces as safe repositories; and hand copying or printing multiple, high-quality versions were all effective ways of preserving knowledge and ensuring that it remained bound to its culture and rooted in truth.

Of course, the calamities of history—including the burning and ransacking of libraries; cultural revolutions; and even moths, roaches, and book beetles—have taken their toll on the strings binding traditions together. The lost works of Aristotle and the meager fragments of Sappho are but two examples of the Fate-severed strings of Western culture. The ancient library of Alexandria, which in its prime supposedly held five hundred thousand volumes within its walls, stands as the great example of a lost culture (Knuth 2003).

Yet even in antiquity people despaired at information overload and the lack of facile resource management. In her 2011 book Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information Before the Modern Age Blair suggests that every age has had to deal with information overload.1 Ecclesiastes 12:12 tells readers to be cautious of too many books.2 Hippocrates in 400 BC tells us, “Ars longa, vita brevis, occasio praeceps, experimentum periculosum, iudicium difficile,” which can be translated as “Technique long, life short, opportunity fleeting, experience perilous, and decision difficult.” Contrary to the oversimplified translation “Art lasts, life [is] short,” Hippocrates instead may have been suggesting that because the acquisition of a skill or a body of knowledge takes a long time, human life is too short in comparison, and the mind is too limited to wield all this learning to perfection.

By the thirteenth century learned people were trying to cope with ever more information. The Dominican Vincent of Beauvais laments on “the multitude of books, the shortness of time and the slipperiness of memory.” The printing press was still two hundred years away, yet people felt dismay at the growth of information. The problem has only grown exponentially since then, even as new technologies have been developed to better meet the problems of information overload.

Enter the Digital Dragon

Jumping ahead to contemporary times, we see that digital technology, no less world altering than Gutenberg’s printing press, has transformed information culture even more. Libraries have in turn made the necessary transition from the physical world to the virtual world, but this technological shift brings practical and philosophical changes. Where the past model for libraries was based on scarcity, new models are based on abundance. Dempsey describes current libraries as moving from an “outside-in” model, in which resources are collected in situ, to an “inside-out” model, in which access points may be available within a library but the actual resources exist outside its walls.3

In the past, libraries struggled to provide as many informational sources as they could with the resources they had. Now, with online resources—some open, but most proprietary in nature—dominating the information landscape, libraries have had to cope with the proverbial water hose turned on at full blast. On the one hand, the amount of information available has increased beyond anyone’s imagination. Services such as Wikipedia, Google Books, and Internet Archive, as well as the open access movement, with its gold open access journals and green open access repositories have each removed many of the barriers to information, especially location and cost. On the other hand, access to information without the ability to distinguish quality, relevancy, and overall comprehensiveness diminishes its impact.

The Digital Library—Early Visions

The discussion thus far has been limited primarily to resource access and the problems of information management in traditional bricks-and-mortar libraries, with a brief nod toward digital models. However, this doesn’t address where the idea for a virtual library began. Certain technologies, economies of scale, and societal advancements needed to exist before the dream of a digital library (DL) could be realized. As in all historical events that seem inevitable, we will see that a large number of developments had to occur simultaneously before the final product could be realized.

The digital library wouldn’t exist without the modern fundamental concept and philosophy of the term digital. While this is a word that appears even in Middle English—referring mostly to counting numbers less than ten fingers—according to the online version of Oxford English Dictionary (www.oed.com), the first mention of the modern concept of digital is in the US Patent 2,207,537 from 1940, which defined the idea as “the transmission of direct current digital impulses over a long line the characteristics of the line tend to mutilate the wave shape.” From this patent, essentially redefining the word as a series of on-off, zero-one switches, the modern digital era was born.

The idea for the first digital library, however, is a little more difficult to pin down. The first mention, and likely most influential inspiration for modern computing, is the Memex from Vannevar Bush’s well-known 1945 article “As We May Think.” Bush described his invention:

[It is] a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.

It consists of a desk, and while it can presumably be operated from a distance, it is primarily the piece of furniture at which he works. On the top are slanting translucent screens, on which material can be projected for convenient reading. There is a keyboard, and sets of buttons and levers. Otherwise it looks like an ordinary desk.4

He provides an astonishingly clear approximation of what the desktop personal computer eventually became in the 1980s and 1990s. However, this vision and its reality took some time to meet in the middle.

By the 1950s and 1960s visions of an electronic or digital library—much clearer than Vannevar Bush’s vision—start to come into focus. Looking at Licklider’s Libraries of the Future from 1965, one can start to see the engineer-centric philosophy of stripping away the book and print materials as an information delivery system from the core of library services. Licklider shows an apt prescience for the main issues of contemporary information science:

We delimited the scope of the study, almost at the outset, to functions, classes of information, and domains of knowledge in which the items of basic interest are not the print or paper, and not the words and sentences themselves—but the facts, concepts, principles, and ideas that lie behind the visible and tangible aspects of documents. (Licklider 1965, my emphasis)

Working in an era of limited computing capacity as well as minimal digital imaging, Licklider and his colleagues were concerned with the transmission of the essential components of the document, be it literature, scholarship, or even a basic list. In other words, they focused on the book’s data and metadata, its context, and its information, establishing the way that most digital projects would later handle texts, by stripping them of the extraneous physical properties that interfere with the so-called purity of the information conveyed. It also points toward document descriptions and other text markup strategies, such as XML, HTML, and XHTML, that later become standards in the field.

Licklider is especially prescient in his suggestion that libraries of the future should not focus as much on physical methods of information delivery—on the “freight and storage” as Douglas Englebart called it in 1963—such as the book and the physical bookshelf, which are, in his mind, incredibly inefficient on a mass scale. Instead, libraries should reject these physical trappings in favor of better methods of information and information processing. The future was promising for what he called “precognitive systems,” which later became the basis of information retrieval (Licklider 1965; Sapp 2002).

He also writes, somewhat reminiscent of Bush in 1945, that engineers “need to substitute for the book a device that will make it easy to transmit information without transporting material, and that will not only present information to people but also process it for them” (Licklider 1965, 6). Here he anticipates what eventually became machine-readable text schemas, but it took at least a generation, beginning in the 1960s with the invention of ASCII code, and running through the 1970s and 1980s, to fully incorporate the digital into this new “text cycle.” Project Gutenberg, one of the original digital libraries to focus on print books, is a great example of the types of digital library stemming from this period.5

The 1970s and 1980s were essential in the development of the tools that would help with the generation of digital texts. As Hillesund and Noring (2006, para. 9) write, “By the 1970s, keyboards and computer screens became the interface between man and computer. Beginning in the 1980s, powerful word processors and desktop publishing applications were developed. The writing and production phases of the text cycle were thus digitized, but the applications were primarily designed to facilitate print production.”

Information retrieval systems began at this time as well with the appearance of Lexis for legal information, Dialog, Orbit, and BRS/Search systems (Lesk 2012). Even though the Library of Congress had pioneered electronic book indexing with the MARC record in 1969, it wasn’t until the 1980s that the online catalog became widespread (Lesk 2012). By the early 1990s the field of information retrieval and its dream of the digital library were on their way to full realization.

Digital Libraries—The Vision Becomes a (Virtual) Reality

When Edward Fox in 1993 looked back on his early days at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) under Licklider, he was able to say with great certainty that “technological advances in computing and communication now make digital libraries feasible; economic and political motivation make them inevitable” (79). He had good reason to be optimistic in his assessment. By this point in time ARPAnet had been around for twenty-four years, the Internet had been born, hypertext developed as a force in the 1980s under such projects as Ted Nelson’s Xanadu, Brown University’s IRIS Project, and Apple’s HyperCard (Fox 1993). The 1990s also saw the development of the HTML protocol, which then gave way to XML and its strong, yet interoperable, framework (Fox 1993). Along with the philosophical framework and software development in the 1980s and 1990s, there was also developing a solid information infrastructure and network from such schemes as Ethernet, asynchronous transfer modes that pushed data transfer speeds from thousands of bits per second to billions (Fox 1993).

By the early to mid-1990s many publishers, libraries, and universities were able to try their hand at creating their own digital collections. Oxford began the Oxford Text Archive, the Library of Congress developed its American Memory Project, and even the French government had planned to digitally scan one million books in the French National Library (Fox 1993).

At this time, multiple visions of what a digital library might entail were also beginning to take form. A digital library was at this point “a broad term encompassing scholarly archives, text collections, cultural heritage, and educational resource sites” (Hillesund and Noring 2006, para. 1). There was little consensus on a specific application and definition. Yet many of the common signposts on the current library digital landscape were in their infancy by this time, and each provided a distinct and important model for a DL. For example, a proto–subject repository for computer science departments to share, archive, and provide search functions for technical reports was developed as a joint project between Virginia Tech, Old Dominion, and SUNY Buffalo. The University of Michigan was pioneering electronic theses and dissertations, and Carnegie Mellon, a full eleven years before Google’s book digitization announcement, was already looking into “distributed digital libraries” with its Plexus Project, with the goal of “developing large-scale digital libraries using hypermedia technology” (Akscyn and McCracken 1993, 11).

Digital Libraries—Uneven Growth, Web 2.0, and Expanding Definitions

By the late 1990s, however, the landscape had grown by leaps and bounds. Google had entered the fray with its revolutionary search engine algorithm, the Internet had exploded on the scene and into most homes, MIT had developed its first DSpace institutional repository system, and e-books were in their infancy.

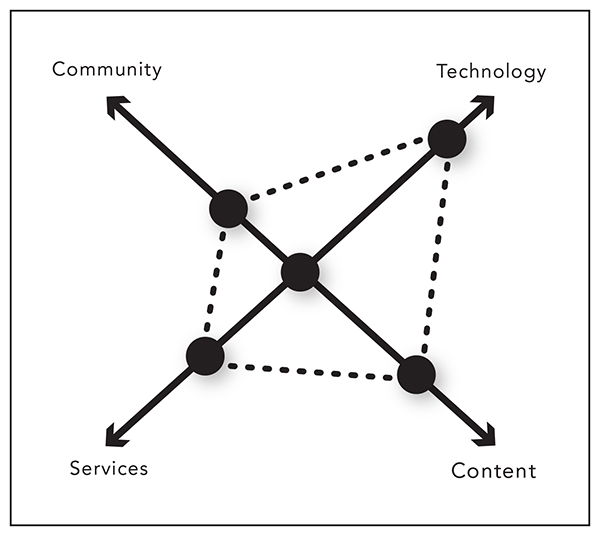

In examining the landscape of the digital library (which most practitioners now called “DL”) as it was in 1999, Marchionini and Fox (1999) noted that digital libraries had entered a second phase, though they had also begun to see some lags in the development of digital libraries. They posited four specific dimensions in the progress of digital libraries: community, technology, services, and content.

As figure 1.1 demonstrates, in their estimation, “progress along these [four] dimensions is uneven, mainly driven by work in technology and content with research and development related to services and especially community lagging” (Marchionini and Fox 1999, 219).

It has turned out that a viable “community,” the element most lagging in this depiction, was really just around the corner. Web 2.0, or social media, was the missing ingredient in the development of digital libraries and their applicability to particular communities. Digital projects would wind up better serving communities by utilizing such technologies as RSS feeds, Twitter, Facebook, and the other multiple “social” web applications.

The definition of the digital library had expanded by the early 2000s to include a large number of online initiatives and digitization projects that included things such as archival collections, cultural sites, educational resources, and even institutional repositories.

Figure 1.1

The four dimensions of digital library progress.

Image redrawn with permission by authors after Marchionini and Fox (1999).

Scholarly archives included digital collections of scanned materials, such as a digital archive, collections of published and unpublished materials, as well as finding aids and other digital text initiatives. Open educational resource sites such as MERLOT and the California Digital Library began to gather learning objects, university scholarship, and other class-related materials. Institutional repositories, which had begun in the late 1990s, burgeoned once an open-source software solution, DSpace, became widely available and supported by various initiatives. Many institutional repository’s collections contain university theses and dissertations (both digitized and born digital), as well as digitized books and book chapters, in addition to the usual peer-reviewed faculty journal articles. These disparate collections of material constitute digital libraries in the sense that they are gathering digital images and OCR text together and indexing them for complex searching (Lesk 2012).

A typical example of the digital library emerging during this phase of development was the International Children’s Digital Library (http://en.childrenslibrary.org). This project initially began with about 1,000 digitized children’s books. It expanded from that time to more than 4,600 books. Its organization has taken care to curate a small but diverse collection of children’s books. It also devised uniquely child-centric methods of searching, including employing a bright, cartoonish user interface and developing a search to identify books by the color of their covers

Digital Libraries—E-Books, MDLs, and Dustbins

Once social media began to affect online accessibility and change how users approached online content, digital libraries reached a critical mass. Around 2005 the aggregation of content from various sources—crowdsourcing, in a sense—began to have an impact on content development. This, as we will see in the next chapter, was spurred in large part by Google and its ambitious announcement that it would digitize every book in the world (Jeanneney 2007).

However, along with the current aggregation of digitized content, born-digital books have also begun to drive content development. At the present date, e-books and their content-delivery hardware devices are starting to finally take off as viable alternatives to print books. In one study released in 2012, the number of Americans using e-books increased from 16 percent to 23 percent in one year.6 It may be that the third phase of the digital library will also see the simultaneous development of mobile devices providing access to the traditional bound long-form narrative. Already books of many types—including directories, textbooks, trade publications, and travel guides—are born digital. This lack of physical form will have a profound impact on the way that people use and process “linear, narrative book-length treatments” (Hahn 2008, 20). Certainly new technologies are adopted and adapted in ways that their original creators never intended. It remains to be seen how and in what manner these technologies will be implemented most effectively.

To end this section, it is important to remember that cautionary tales exist even in the digital library world, despite its relatively recent appearance. One of the largest digitization projects during the late 1990s and early 2000s was Carnegie Mellon’s Million Books Project. By 2007, it had finished its mission of digitizing and placing online a full collection of books in various languages. Unfortunately, much like the ICDL and its small-scale collection, the Million Books Project has been superseded by the next generation of massive digital libraries. Currently the software and servers for the Million Books Project—now known as the Universal Digital Library (www.ulib.org)—are not well maintained. Sustainability, so eloquently defined and described on the Universal Digital Library’s informational pages, is proving to be much less possible than anticipated. The unclear fate of this project—it’s still available online but has neither been updated nor improved upon—provides us a glimpse into the likely future of many current digital projects. They become more examples of technology relegated to Trotsky’s “dustbin of history,” now providing more of a precariously unstable web history lesson than a useful service.

References

Akscyn, Robert, and Donald McCracken. “PLEXUS: A Hypermedia Architecture for Large-Scale Digital Libraries.” In SIGDOC ’93: Proceedings of the 11th Annual International Conference on Systems Documentation, 11–20. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 1993. doi: 10.1145/166025.166028.

Englebart, Douglas. 1963. “A Conceptual Framework for the Augmentation of Man’s Intellect.” In Vistas in Information Handling, edited by P. Howerton and D. Weeks, 1:1–29. Washington, DC: Spartan Books.

Fox, Edward. 1993. “Digital Libraries.” IEEE Computer 26, no. 11: 79–81.

Hahn, Trudi Bellardo. 2008. “Mass Digitization: Implications for Preserving the Scholarly Record.” Library Resources and Technical Services 52, no. 1: 18–26.

Hillesund, Terje, and Jon E. Noring. 2006. “Digital Libraries and the Need for a Universal Digital Publication Format.” Journal of Electronic Publishing 9, no. 2.

Jeanneney, Jean-Noël. 2007. Google and the Myth of Universal Knowledge: A View from Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. First published in French in 2005.

Knuth, Rebecca. 2003. Libricide: The Regime-Sponsored Destruction of Books and Libraries in the Twentieth Century. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Lesk, Michael. 2012. “A Personal History of Digital Libraries.” Library Hi Tech 30, no. 4: 592–603.

Licklider, J. C. R. 1965. Libraries of the Future. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Marchionini, Gary, and Edward A. Fox. 1999. “Progress toward Digital Libraries: Augmentation through Integration.” Information Processing and Management 35, no. 3: 219–225.

Sapp, Gregg. 2002. A Brief History of the Future of Libraries: An Annotated Bibliography. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Notes

1. See Jacob Soll, “Note This,” review of Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age, by Ann M. Blair, New Republic, August 24, 2011, www.newrepublic.com/article/books-and-arts/magazine/94175/ann-blair-managing-scholarly-information.

2. Ann Blair, “Information Overload’s 2,300-Year-Old History,” HBR Blog Network (blog), http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2011/03/information_overloads_2300-yea.html.

3. Lorcan Dempsey, “‘The Inside Out Library: Scale, Learning, Engagement’: Slides Explain How Today’s Libraries Can More Effectively Respond to Change,” OCLC Research, February 5, 2013, www.oclc.org/research/news/2013/02-05.html.

4. Vannevar Bush, “As We May Think,” Atlantic Monthly, July 1945, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/.

5. Michael Hart, “The History and Philosophy of Project Gutenberg,” Project Gutenberg, August 1992, www.gutenberg.org/wiki/Gutenberg:The_History_and_Philosophy_of_Project_Gutenberg_by_Michael_Hart.

6. Lee Rainie and Maeve Duggan, “E-Book Reading Jumps; Print Book Reading Declines,” Pew Internet and American Life Project, December 27, 2012, http://libraries.pewinternet.org/2012/12/27/e-book-reading-jumps-print-book-reading-declines/.