The Copyright Conundrum—or, How Is This Allowed?

We are the first generation to deny our own culture to ourselves.

—Tweet by James Boyle, Duke Law School professor, @thepublicdomain

A Copyright Conundrum

The story of copyright is tied inextricably to technological changes. The printing press, the development of the book itself, the adoption of cheaper materials and faster, more efficient modes of content distribution (including ocean travel, railways, automobiles, airplanes, and finally digital files and the Internet)—all these have had an impact on copyright law. The influence of these changes is not to be downplayed. In fact, copyright law in the digital age is struggling to currently keep pace with the rapid changes in digital distribution platforms, including the development of peer-to-peer sharing networks, e-book readers, digital rights management technologies and policies, and the like.

Authors are often cited as the main beneficiaries of copyright, especially in terms of marketing and piracy protection.1 Yet most authors or creators, except for the few who actually become truly self-sufficient, rarely benefit financially from copyright protection. In fact, as scholar Paul Heald has found for most authors or creators—many of whom would likely prefer to see their work disseminated much more widely—copyright law actually creates a dampening effect on the distribution of their works.2 As seen in figure 5.1, although the public domain allows users to adapt and utilize content openly and without restriction for the advancement of culture, science, and society, works are being kept away from the public for much longer than ever in history. Currently, the United States is enduring a public domain freeze, and works will not begin to pass into the public domain again until 2019.3

Figure 5.1

Copyright law severely limits accessibility to works in copyright. The number of editions available of material from 1910 is greater than that of the last decade. (Courtesy of Paul Heald)

So how is it possible that a series of laws set up nominally to help a particular group of people can simultaneously have a negative influence on the culture as a whole? Furthermore, how can a set of laws that are essentially antitrust in nature—creating quasi fiefdoms of cultural and intellectual matter—exist in a capitalist society, which usually encourages competition at the expense of stability?

This is the copyright conundrum, and there are reasons for this current contradictory state of affairs. These contradictions have always existed, but the appearance of MDLs has brought copyright issues to light on a much larger scale.

A Brief History of Copyright

When looking at the history of copyright, both with early and recent copyright precedents, it becomes clear that the force driving the development and extension of copyright law comes not from a need to protect authors and creators—although the law does at times protect them from blatant piracy and theft—but from a need to preserve the interests of the distributors and publishers of the content. Indeed, it is often the distributors who benefit most from copyright laws, not authors or creators. This distinction makes many of the motives for recent copyright lawsuits that occur in the name of authors much more coherent. In Cambridge University Press v. Becker (see Schwartz 2012), which involved three publishers (Oxford University Press, Sage Publications, and Cambridge University Press) suing Georgia State University over copyright infringement in online course reserves, is a fine case in point (Schwartz 2012).

Copyright law has developed in tandem with technological innovations—especially the printing press and improved infrastructure—since the early 1600s, but it also began in a rather dubious manner. In England, the first copyright policies were developed as a way to curtail the free flow of information, which was seen as a destabilizing force in their society. Indeed, the first copyright office, the London Stationers’ Company, was “granted a royal monopoly over all printing in England, old works as well as new, in return for keeping a strict eye on what was printed.”4 The invention of the printing press in 1440 had created a boon in the amount of texts available, but the English monarchy deemed some of those texts “seditious” and dangerous. As a result, the stationers were charged with stemming the tide of revolutionary ideas.

From this model copyright continued to develop out of this de facto monopolization of printable content. In 1709 the very first law regarding copyright was enacted, the Statute of Anne, which limited copyright length to fourteen years and

transformed the stationers’ copyright—which had been used as a device of monopoly and an instrument of censorship—into a trade-regulation concept to promote learning and to curtail the monopoly of publishers. . . . The features of the Statute of Anne that justify the epithet of trade regulation included the limited term of copyright, the availability of copyright to anyone, and the price-control provisions.5

Essentially, copyright shifted from a censoring role to a more regulatory one.

In the United States, the copyright laws of 1790 were written as the new nation was being developed, yet the new laws were similar to the Statute of Anne, from nearly eighty years earlier. In the United States, copyright was originally limited to one term of fourteen years, with the possibility of extension for another fourteen years.

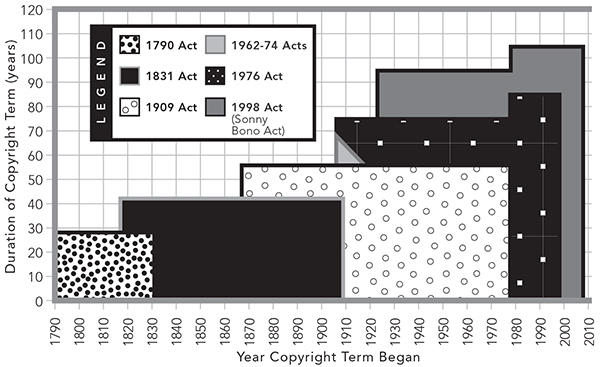

Over the decades and into the twentieth century, however, the story of copyright is one of lengthening and increasingly stricter interpretations of the meaning of copyright restriction. The shrinking of the public domain is a direct result of longer and more restrictive copyright protections (see figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2

Copyright term lengths in the United States have increased since the original act of 1790. The current copyright length since the 1998 Copyright Extension Act is seventy years plus the life of an author.

(Chart assumes authors have created their works at age thirty-five and live for seventy years).

© Tom Bell. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Each subsequent copyright act in the United States has created longer terms for protection, and the main act that affects everyone to this day, the Copyright Act of 1976, closed several avenues for copyright lapses and granted complete protection to all works regardless of whether the creators had followed procedures to register the work or not. This carte blanche application of copyright to all works reduces confusion about whether works are copyrighted or in the public domain, but it does provide some issues in enforcement, especially with regard to orphan works.

Current Copyright Law

Overview

Despite these lengthening and increasingly strict interpretations of the rules, the basics of copyright remain the same: authors or creators (or those to whom such rights are transferred) are granted automatic rights to prevent others from making unauthorized copies or distributing their work. Without these, many argue, the livelihoods of artists, creators, publishers, and distributors of content would be in jeopardy.

The most important current statutes in US copyright law are the 1976 Copyright Act; the 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act (also known as the Sonny Bono Act, for the actor-turned-senator who initiated the law); and the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), created partly at the behest of the largest employer in Bono’s district, Disney Corporation. Each of these acts provides the pillars for current copyright law and enforcement.

The 1976 Copyright Act established some of the copyright basics currently in effect, including the granting of automatic rights without having to register the works with the Copyright Office and the increased length of protection for a work, from an earlier fifty-six-year maximum to the life of an artist plus fifty years.

The 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act increased the length of protection for a work to the life of an author plus seventy years. Given that the term was extended to meet a few specific distributors’ interests, it should be expected that another extension will be in the works by the next decade. Indeed, as of summer 2013, Congress had begun to take another look at revising copyright laws and creating “the next great copyright act” at behest of the US Copyright Office (Pallante 2013).

The 1998 DMCA provided distributors much farther-reaching control over the private use and ability for users to copy digital files by criminalizing infringement. The act also proscribes people from damaging or altering any digital rights management (DRM) software or devices designed to prevent unauthorized copying. Aside from its questionable tactics of impinging upon a person’s right to the private use of an item he or she has purchased, the statute has been criticized for stifling free expression and violating computer intrusion laws.6

Yet, despite DRM, proscriptive copyright laws, and other statutes being ostensibly more favorable to copyright holders, these limitations are not the whole story of copyright. There are several important exceptions to copyright that users of content can freely utilize.

Public Domain

The public domain is essentially any work that exists outside of copyright protection and is thus freely usable by anyone to adapt, change, or republish. However, the rationale behind creating a vital public domain is described quite well by the Europeana Foundation, operator of the MDL of the European Union, at its website (www.publicdomaincharter.eu): “The public domain is the raw material from which we make new knowledge and create new cultural works.” A commons like the public domain provides a shared basis from which new knowledge and new artistic endeavors and progress can occur. New theories, ideas, concepts, and technologies would not exist without models from previous centuries. Indeed, Isaac Newton, when describing his invention of the calculus, said, “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” But with an incredibly shrinking public domain within the United States, the current length of the copyright term might be better described as giants standing on our shoulders.

Works enter the public domain for various reasons, the most common of which is age. Anything published before 1923, or unpublished before 1894, has entered the public domain. These works can be used freely by anyone without permission. Furthermore, many US states and the US government publish their works directly into the public domain, providing little or no restrictions on their use. Additionally, many works that existed before the 1976 Copyright Act have passed into the public domain through noncompliance with some of the regulations of the time. For example, if someone published a work in 1957 without affixing the © symbol to it, and failed to register that work with the US Copyright Office, then the work automatically passed into the public domain. The frequency of works passing into the public domain in this fashion is not known, but as Gerhardt (2013, 4) describes it:

This system provided many public benefits. It fed many works into the public domain immediately, and many others entered after less than three decades. It also provided clarity, because if one knew the work was published, the presence or absence of notice clearly indicated which path was selected. When an author did not choose the path of protection, the default route led straight to the public domain.

Open Content Movements: Creative Commons, Open Access, and Open Source

The copyright laws as enforced from March 1989 have muddied the clarity that used to exist in the law. Now one must track down authors to determine the extent of permissions allowed. However, open content movements have sprouted to address this issue. There are many creators and writers who freely waive their rights using certain licenses that predetermine how users can alter, use, or even distribute their works. There is essentially a new content community growing parallel to the current copyright-restricted one. For example, the open access movement allows users to freely view, read, and comment on published materials. The other is the Creative Commons licensing movement, in which creators can predetermine the extent of the rights they wish to waive in order to allow others to use, modify, or repurpose to suit their needs by affixing a CC license to their works.

Sometimes this movement toward open content is aligned with educational or national mandates. For example, the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation have mandated that data generated by public funding must be made available to all users. Other institutions have created open educational resources (OERs) to allow educators and students to enhance classroom learning objectives. One example is MERLOT, an OER content aggregator that draws content in from various repositories. Generally, current copyright law would prohibit such free exchange and reuse of content, but with specific licenses applied to works, copyright litigation can be avoided. As long as users don’t abuse the license or reach beyond the tenets of fair use, then the models can work tolerably well.

Ultimately, these open access movements prove that copyright need not induce fear. The motivation for these organizations is the fostering of ideas and the exchange of information—all for the progress of disciplines.

Fair Use

Fair use is probably the strongest of all the exemptions to copyright, and it is one of the most flexible, blurred, and ultimately misunderstood of the exemptions. It is frequently referred to as breathing room to allow for the freedom of expression within copyright law.7 Fair use has a framework of four criteria to determine whether it is permitted to use a particular copyrighted work. The four factors are the purpose and character of the use, the nature of the original material to be used, the amount and substantiality of the material used, and the economic impact that its use will have on the creator or copyright owner. The person trying to determine fair use weighs each of the four factors equally and, ideally, makes a reasoned decision on using or not using something.

If something is determined as a fair use, then the users of copyrighted materials can use the work without written permission. Generally, fair uses are scholarly, nonprofit, critical, and transformative in purpose. As a result, nonprofit universities and schools have a strong foundation for using works fairly, which also means that for-profit universities and businesses have a much harder time using works without permission.

Overall, fair use is widely downplayed by distributors and publishers, and even authors, to some extent. However, it is a powerful tool for providing people with the ability to comment on, change, and adapt old models and old ideas into something new. And it is a powerful exception to the seemingly authoritarian restrictions of copyright owners.

A Note on Orphan Works

Orphan works are those published materials for which it is not easy to determine the copyright owner. Sometimes companies go out of business. Sometimes children or grandchildren of the original owner are unaware that they are rightful owners of content. Sometimes authors have given up seeking compensation or claims upon their works. Sometimes people cannot be reached to secure permission. In those situations, where the copyright owner is not accounted for or is deemed unreachable, the work is determined to be an orphan work. It’s still under copyright, but copyright may not be enforceable.

Yet the rights still remain firmly in the hands of the putative copyright owners. As a result, people sometimes come out of the woodwork to claim ownership. A main obstacle for MDLs with respect to copyright is the preponderance of such orphan works. The lack of express permissions to digitize and place certain works online is a huge impediment to the development of MDLs. Indeed, as of June 2013, the Authors Guild v. HathiTrust ruling was being contested on issues related to orphan works.8

The issue of orphan works is more common, though, with archives and special collections, where people’s unpublished letters and accounts are afforded much longer copyright terms, and, due to the age of the documents, the copyright holders are harder to track down . The digitization of such collections often requires due diligence and good faith. As long as archives follow due diligence these precautions regarding orphan works are often unnecessary, and since letters of request to use the works are usually kept on file at an archive, most of these issues with orphan works tend not to arise.

However, the simplest solution to avoid liability has been for historical organizations to digitize their holdings but completely eschew posting the materials online. MDLs face similar situations, but have so far, at least in the case of Google, proved much bolder in their approach.

Impact of the Digital Age

All new information technologies have had an impact on copyright law. However, the digital age has likely had the most profound of all impacts. The Internet functions both as a device that is capable of providing easy communication and as the “world’s largest copy machine.”9 Thus, use of the Internet can circumvent many of the distribution and publication industries that built up around various artistic, scientific, and other cultural creations.

As a direct result of Internet users’ ability to communicate and spread content verbatim, several industries, including the Recording Industry Association of America and the Motion Picture Association of America, became fearful for their livelihoods and compelled Congress to act. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) is one such result. By criminalizing attempts to dismantle digital rights management software or other similar technologies, the distributors of content are able to protect their livelihoods. At the same time, criminalizing the circumventing of already-questionable tactics to preserve profit margins arguably impedes the basics of fair use. In many ways, then, if people are unable to use fair use as a defense against draconian content restrictions, the future of fair use comes into question. There is some evidence, though, that courts still favor fair use despite the restrictions spelled out in the DMCA. A ruling in 2010 determined that breaking DRM software code or the restrictions imposed on the hardware for legitimate and fair use reasons should be allowed: “Merely bypassing a technological protection that restricts a user from viewing or using a work is insufficient to trigger the DMCA’s anti-circumvention provision.”10 The implication may be that something considered fair use should not be cause for legal action just because the technological protections built into digital media prevent any unintended uses. For example, a person attempting to copy a CD for personal use—often considered fair use—may need to dismantle the DRM software installed into the disk to copy it. DRM software prevents a person from using the disk beyond playback, thereby encroaching on a person’s potential right to repurpose and transform it, as a producer, DJ, or musician would. Suggesting the legality of dismantling overrestrictive software—if deemed a fair use, that is—would allow for the breathing room necessary for end users.

The Impact of MDLs on Copyright Law

It would be an understatement to say that MDLs have had some impact on copyright law. MDLs can be seen as logical extensions of the Internet’s early promise of being an information superhighway. Yet there has been intense backlash from all sides against MDLs. Indeed, the two largest MDLs, HathiTrust and Google Books, have been saddled with high-profile lawsuits since the mid-to late 2000s. In this section we look at those cases and provide an overview of why they are important to libraries and the impact they are likely to have on the future of publisher-library cooperation and on both industries individually.

Authors Guild v. Google Books

Without a doubt the best-known lawsuit regarding publishers, authors, and digital libraries is Authors Guild Inc. v. Google, Inc.11 At stake in this case are numerous issues, the most important of which is whether Google’s digitization of millions of books can be considered fair use. The case hinges upon an analysis of Google Books and the four factors of fair use. Some commentators have argued that Google’s claim of fair use may be mischaracterization of the legal framework and may eventually damage the fair use defense. Samuelson argues, for example, that “if one of Google’s rivals aims to develop a commercial database like GBS [Google Book Search] when it starts scanning, it won’t have a fair use leg to stand upon.”12 Additionally, Kevles (2013) finds fault with the millions of digitized magazines that are falling through the cracks and the possibility that accessibility for the blind and other disabilities is outweighed by potential reductions in civil rights.

Although Google had already begun digitizing texts in the early 2000s, the results had not been visible in its searchable online database Google Books until 2004. Initial action against Google from the Authors Guild began in 2005, less than one year after Google launched its Google Books project. By 2006, both parties had begun negotiations to settle. It wasn’t until October 2008, however, that the parties proposed a settlement agreement, which included Google compensating the Authors Guild $125 million. Some of the money would be used to create the Book Rights Registry. This would allow authors or other rights holders to collect compensation from Google. The settlement was amended in 2009 and excluded foreign works published outside the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia. The settlement was delayed further as the courts examined the settlement agreement beginning in February 2010. A ruling in March 2011 was released, rejecting the settlement.13 As recently as May 2013, however, more plaintiffs, including the American Photographic Artists, joined the lawsuit.14

The amended settlement agreement was rejected on several grounds, including the fact that the agreement itself seemed to “transfer to Google certain rights in exchange for future and ongoing arrangements, including the sharing of future proceeds, and it would release Google (and others) from liability for certain future acts.”15 As the case noted, the agreement also exceeded the scope of the case itself and “would release claims well beyond those contemplated by the pleadings.”16

In November 2013, however, the Authors Guild v. Google case was finally ruled on by Judge Denny Chin, who found that the fair use defense employed by Google Books with regard to its display of only “snippets” of content for copyright works was justifiable.17 In his ruling, the judge advocated quite positively for the project:

Google Books provides significant public benefits. It advances the progress of the arts and sciences, while maintaining respectful consideration for the rights of authors and other creative individuals, and without adversely impacting the rights of copyright holders. It has become an invaluable research tool that permits students, teachers, librarians, and others to more efficiently identify and locate books. It has given scholars the ability, for the first time, to conduct full-text searches of tens of millions of books. It preserves books, in particular out-of-print and old books that have been forgotten in the bowels of libraries, and it gives them new life. It facilitates access to books for print-disabled and remote or underserved populations. It generates new audiences and creates new sources of income for authors and publishers. Indeed, all society benefits.18

This ruling appears to focus primarily on the immediate social benefits that the Google Books project provides users, although the phrase “without adversely impacting the rights of copyright holders” is certainly debatable. In particular, the emphasis on “old books that have been forgotten in the bowels of libraries” is a particularly cogent point. Many of the works on Google Books are indeed out of print and their accessibility impeded by physical and organizational barriers. Additionally, publishers have chosen for various reasons, as seen in Paul Heald’s research earlier in this chapter, to not republish or provide further access to them in the form of new editions.19 Although libraries provide access to these works to those outside their main constituencies via interlibrary loan partnerships, these are costly and slower in comparison.

However, with the extremely volatile nature of for-profit business, the long-term effects of Google Books do not seem to be of as much importance in this case. It remains to be seen whether Google Books’ social benefits are sustainable, especially if bottom-line profitability remains the primary mode of the project’s effectiveness. Google’s tendency in the past to pull the plug on various unprofitable projects should cause concern for the unpredictable future of Google Books.

Despite that it lost the case, the Authors Guild’s main criticism of Google remains the same. According to the guild, Google continues to profit from its use of millions of copyright-protected books while failing to reward authors. Since the ruling the Authors Guild has stated its disagreement and dissatisfaction, and as of December 30, 2013, it had already provided a basic notice of appeal to the US Court’s Second Circuit.20 The case, therefore, is likely to continue through appeals for the foreseeable near future.

Authors Guild v. HathiTrust

Authors Guild v. HathiTrust is in some ways counterpoint to the ongoing Google Books copyright case.21 Although there are similarities in the cases, the case against HathiTrust turns on the development of precautions and transformative uses that it appears Google never considered.

The Authors Guild contended that by digitizing and indexing several millions of works, HathiTrust committed serious copyright infringement. The HathiTrust university consortium, which includes the University of Michigan, however, defends its actions as fair use. The lawsuit began September 2011 and was ruled on October 11, 2012—in contrast to the eight-year Google Books lawsuit. In the end the judge ruled in favor of HathiTrust.

Fair use was central to the defense of HathiTrust’s digitization effort. Essentially, the court held that the goal of promoting science would be met more by allowing use than by preventing it:

The enhanced search capabilities that reveal no in-copyright material, the protection of Defendants’ fragile books, and perhaps most importantly, the unprecedented ability of print-disabled individuals to have an equal opportunity to compete with the sighted peers in the ways imagined by the ADA protect the copies made by Defendants as fair use.22

The holding suggests that libraries that digitize materials for purposes of transformation, preservation, noncommercial use, and compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act fall well within the fair use doctrine. Also noteworthy—and this is a flaw of the HathiTrust MDL itself—is that access to copyrighted materials is entirely limited to text mining. Actual content itself is not available for others to see. This limitation helped HathiTrust to avoid any liability in terms of copyright infringement. The court concluded: “I cannot imagine a definition of fair use that would not encompass the transformative uses made by Defendants’ [mass digitization project].”23

The implications of this ruling are important for all libraries. As long as they stay within fair use guidelines, digitization projects of text materials have set a precedent helping to defend their actions beyond the basic preservation of materials. In this case fair use includes transformative indexing and full-text searching, preservation of source materials via digital copies, adhering to strictly noncommercial and scholarly activities, and creating collections of materials that help the visually impaired in order to adhere to the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The future may be brighter for MDLs that follow the more cautious service-oriented and educational model espoused by the HathiTrust. However, as of summer 2013 some dark clouds were gathering again. The Authors Guild filed an appeal contesting the 2012 ruling in 2013 and it remains to be seen what happens as the saga may not be over yet.24

Fighting for the Public Domain: Europeana

Aside from litigation, some MDLs have taken up issues within copyright and culture by attempting to change legal frameworks and take on stronger roles in advocacy. Europeana, the MDL that incorporates the cultural materials of hundreds of European cultural institutions, has created a policy for developing a stronger public domain. Europeana appears to have an active respect for and desire to encourage the development of the public domain.

Europeana’s Public Domain Charter (www.publicdomaincharter.eu) states three principles for a healthy public domain. The first principle is “Copyright protection is temporary,” a reminder that the statutes of copyright are meant to be short term. It can be inferred that the MDL’s intent is also to suggest that the shorter the exclusivity in copyright law, the stronger the public domain will become. The second principle states, “What is in the public domain needs to remain in the public domain.” Recent court cases in the United States show a trend of allowing works to be recopyrighted. For example, in Golan v. Holder the Supreme Court held that works can be put back into copyright protection, thus adjusting the law to allow the United States to move into better compliance with the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, an international agreement on copyright protection first established in Berne, Switzerland, in 1886.25 This precedent does not bode well for ensuring that works that have passed into the public domain remain there. The third principle of the Europeana Foundation is “the lawful user of a digital copy of a public domain work should be free to (re-)use, copy and modify the work.” Essentially, creativity and new knowledge cannot be developed without the free use of old models, which was how cultures progressed for thousands of years.

The Europeana policy also takes other current developments in copyright to task, including the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) of 1998 and the Google Books project, which pairs corporate interests with cultural ones. As for the DMCA and similar decrees that criminalize what might actually be fair use, the Europeana Foundation in its Public Domain Charter avers that “no other intellectual property rights must be used to reconstitute exclusivity over Public Domain Material.” The DMCA prohibits any users from dismantling data rights management software or devices in any circumstances. While this is useful for the distributors or publishers of content, it prevents users from exercising their fair use rights and could, if a work were actually in the public domain, prevent people from fully using the source material. Indeed, according to the Europeana Foundation, “No technological protection measures backed-up by statute should limit the practical value of works in the public domain.”

In the case of Google Books or similar corporate-cultural hybrid projects, Europeana warns against allowing proprietary interests to lock down content by exploiting exclusive relationships. According to the Europeana Foundation, such commercial content aggregators are “attempting to exercise as much control as possible over . . . public domain works.” It warns that whether in analog or in digital form, works that were freely accessible should not be compromised.

Overall, the Europeana vision is one that aligns much with many of the values of European cultural organizations as well as those of the United States—and indeed, those of the whole world. Jeanneney’s cri de coeur from 2007 right after Google announced its intentions to enter the digitization game appears to have had an impact on the development of this particular MDL. Currently, though, given its size, Europeana appears to be on solid footing and poised to be a strong advocate for the free and open use of online public domain materials.

It is clear that MDLs are having a large impact on the landscape of copyright. Despite its recent victorious ruling, Google appears to have a long legal fight on its hands. Some of its problems stem from the proprietary nature of its endeavor. If Google were to abandon the primary focus on profit making or perhaps alter the fundamental purpose of their program, it might be seen in a better light. HathiTrust seems to have weathered the copyright lawsuit storm well and is poised to develop as the leader of MDLs in terms of copyright compliance and providing access to public domain works and access to those works by people with disabilities. Finally, Europeana’s efforts to advocate for a strong and robust public domain make it a worthy cause to follow. Hopefully these MDLs will continue to fight for strong and clear open access of cultural content disambiguated from the profit motives of corporations.

References

Gerhardt, Deborah. 2013. “Freeing Art and History from Copyright’s Bondage.” UNC Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2213515. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2213515.

Kevles, Barbara. 2013. “Will Google Books Project End Copyright?” AALL Spectrum 17, no. 7 (May): 34–36, 47. www.aallnet.org/main-menu/Publications/spectrum/Archives/vol-17/No-7/google-books.pdf.

Pallante, Maria. 2013. Statement of Maria A. Pallante Register of Copyrights, US Copyright Office before the Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property and the Internet Committee on the Judiciary. US House of Representatives, 113th Congress, 1st Session, March 20. www.copyright.gov/regstat/2013/regstat03202013.html#_ftn1.

Schwartz, Meredith. May 17, 2012. “Georgia State Copyright Case: What You Need to Know—and What It Means for E-Reserves.” Library Journal, May 17. http://lj.libraryjournal.com/2012/05/copyright/georgia-state-copyright-case-what-you-need-to-know-and-what-it-means-for-e-reserves/#_.

Notes

1. “Guild Tells Court: Reject Google’s Risky, Market-Killing, Profit-Driven Project,” Authors Guild, September 17, 2013, www.authorsguild.org/category/advocacy/.

2. Rebecca Rosen, “The Hole in Our Collective Memory: How Copyright Made Mid-Century Books Vanish,” Atlantic, July 30, 2013, www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/07/the-hole-in-our-collective-memory-how-copyright-made-mid-century-books-vanish/278209/.

3. John Mark Ockerbloom, “Public Domain Day 2010: Drawing up the Lines,” Everybody’s Libraries, January 1, 2010, http://everybodyslibraries.com/2010/01/01/public-domain-day-2010-drawing-up-the-lines/.

4. “The Surprising History of Copyright and the Promise of a Post-Copyright World,” http://questioncopyright.org/promise.

5. Ibid.

6. “DMCA Digital Millennium Copyright Act,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, 2013, www.eff.org/issues/dmca.

7. “Guidelines and Best Practices,” University of Minnesota Libraries, 2010, www.lib.umn.edu/copyright/guidelines.

8. “Authors’ Orphan Works Reply: The Libraries and Google Have No Right to ‘Roll the Dice with the World’s Literary Property,’” Authors Guild, June 25, 2013, www.authorsguild.org/advocacy/authors-orphan-works-reply-the-libraries-and-google-have-no-right-to-roll-the-dice-with-the-worlds-literary-property/; “Remember the Orphans? Battle Lines Being Drawn in HathiTrust Appeal,” Authors Guild, June 7, 2013, www.authorsguild.org/advocacy/remember-the-orphans-battle-lines-being-drawn-in-hathitrust-appeal/; see also Authors Guild v. HathiTrust, 902 F.Supp.2d 445, 104 U.S.P.Q.2d 1659, Copyr.L.Rep. ¶ 30327 (October 10, 2012).

9. Lena Groeger, “Kevin Kelly’s 6 Words for the Modern Internet,” Wired Magazine, June 22, 2011, www.wired.com/business/2011/06/kevin-kellys-internet-words/.

10. “Ruling on DMCA Could Allow Breaking DRM for Fair Use,” Electronista, July 25, 2010, www.electronista.com/articles/10/07/25/court.says.cracking.drm.ok.if.purpose.is.legal/#ixzz2do0ASJv5.

11. Authors Guild v. Google, Case 1:05-cv-08136-DC, Document 1088 (November 14, 2013).

12. Pamela Samuelson, “Google Books Is Not a Library,” Huffington Post, October 13, 2009, www.huffingtonpost.com/pamela-samuelson/google-books-is-not-a-lib_b_317518.html.

13. Andrew Albanese, “Publishers Settle Google Books Lawsuit,” Publisher’s Weekly, October 5, 2012, www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/digital/copyright/article/54247-publishers-settle-google-books-lawsuit.html.

14. Mike Masnick, “American Photographic Artists Join the Lawsuit against Google Books,” Techdirt, April 25, 2013, www.techdirt.com/articles/20130416/17225622732/american-photographic-artists-join-lawsuit-against-google-books.shtml.

15. Andrew Albanese and Jim Milliot, “Google Settlement Is Rejected,” Publisher’s Weekly, March 22, 2011, www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/digital/content-and-e-books/article/46571-google-settlement-is-rejected.html.

16. Ibid.

17. Stephen Shankland, “Judge Dismisses Authors’ Case against Google Books,” CNET News, November 14, 2013, http://news.cnet.com/8301-1023_3-57612336-93/judge-dismisses-authors-case-against-google-books/.

18. “Judge Denny Chin Google Books Opinion,” CNET News. 2013, www.scribd.com/doc/184176014/Judge-Denny-Chin-Google-Books-opinion-2013-11-14-pdf.

19. Rebecca Rosen, “The Hole in Our Collective Memory: How Copyright Made Mid-Century Books Vanish,” Atlantic, July 30, 2013, www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/07/the-hole-in-our-collective-memory-how-copyright-made-mid-century-books-vanish/278209/.

20. “Authors Guild Appeals Google Decision,” Publishers Weekly, December 30, 2013, www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/digital/content-and-e-books/article/60492-authors-guild-appeals-google-decision.html.

21. Authors Guild v. HathiTrust, 902 F.Supp.2d 445, 104 U.S.P.Q.2d 1659, Copyr.L.Rep. ¶ 30327 (October 10, 2012).

22. Quoted in the American Council on Education’s Amicus Brief: Authors Guild v. HathiTrust Digital Library, June 4, 2013, www.acenet.edu/news-room/Pages/Amicus-Brief-Authors-Guild-v-HathiTrust-Digital-Library.aspx.

23. Ibid.

24. “Remember the Orphans? Battle Lines Being Drawn in HathiTrust Appeal,” Authors Guild, June 7, 2013, www.authorsguild.org/advocacy/remember-the-orphans-battle-lines-being-drawn-in-hathitrust-appeal/.

25. Golan v. Holder. 132 S. Ct. 873 (2012).