Collection Diversity—or, Why Is This Missing?

Diversity of Content: Why Is This Missing?

The American Library Association (ALA) actively promotes diversity in collections and urges libraries to “collect materials not just representative of dominant societal viewpoints, but also of the views of historically underrepresented groups within society” (LaFond 2000). This stance encourages libraries to broaden collections so that people might be challenged as well as inspired. The root of academic freedom, central to the ALA’s core mission, lies with this need for collection diversity. Without it, libraries would be merely mirrors of dominant cultures rather than spectra holding an array of cultures.

However, given the current limitations on budgets facing all libraries, as well as the sheer numbers of materials published yearly, complete diversity cannot exist in any library, even the best-funded ones. However, that does not mean that libraries cannot at the very least attempt to meet the needs of multiple users.

Diversity is directly related to a library’s collections development policy. For example, the University of Hawaii at Manoa is one of the world’s largest collectors of Hawaii- and Pacific-related materials, focusing as much on the Japanese and Okinawan immigrant experience as on the native Hawaiian experience. Its collection development policy fuels its commitment to diversity, and vice versa. Yet its mission is one that must remain focused purely on its constituents. It is entirely unreasonable, for example, to expect a small, private, liberal arts institution like Kenyon College in Gambier, Ohio, for example, to collect Hawaiian and Pacific materials to such a large degree. No one would accuse the college’s library of not being diverse enough just on the basis of the number of Hawaiian and Pacific materials in its collection. Some context and intention needs to be factored in.

Nevertheless, diversity is an important aspect of developing collections. Without a strong sense of constituents, one’s collections may not adequately address user needs. MDLs are no different. The diversity of content may not be ideal in MDLs. Indeed, there are specific issues related to diversity of content within MDLs, including Google Books, HathiTrust, Internet Archive, and Open Content Alliance (Weiss and James 2013). But given the ability of MDLs to quickly create collections, the issues involved may be easier to solve than those of bricks-and-mortar institutions.

How MDLs Were Created Leads to Concerns about a Lack of Diversity

The diversity of content in the Google Books project or any of the other MDLs remains at the mercy of the partnerships the MDL has created. In the case of Google Books the partners added include collections from Spain, Germany, and France, as well as a major Japanese collection. Given the huge number of books and languages in the world, one must question whether such partnerships are actually fruitful. To have universal coverage, one would need to add everything. However, as discussed in chapter 6, given the physical limitations of books, this is not a feasible outcome for creating a digital corpus of everything printed. Of course, it is also important that at least MDLs find partners to fill in the missing subject matters. In this case, something is better than nothing.

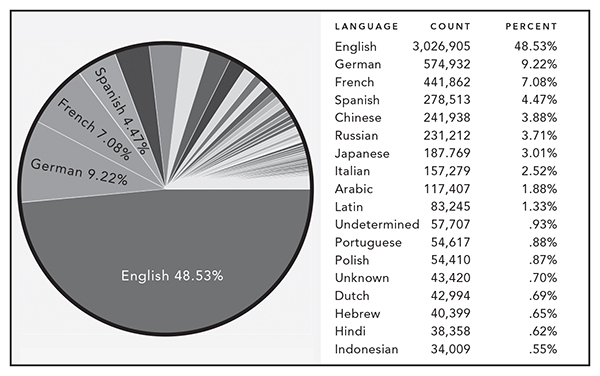

For the HathiTrust, the same issues exist. The number of partners is large, but still not worldwide comprehensive. According to its online statistics, the percentage of English-language books in the MDL remains at about 50 percent. Of the top ten languages represented, 60 percent are Indo-European, with one, Latin, a dead language. Two are East Asian languages (Chinese and Japanese) and one is Slavic (Russian).1 By world population and the number of cultural artifacts created by various cultures—especially those that are older than the United States by millennia—the collections are disproportionately skewed toward the English language. Again, like the Google Books project—and in part because many of the HathiTrust partners are shared with Google Books—the issue of the source materials calls into question the ability of MDLs to create truly diverse collections. Figure 7.1 shows the distribution of languages. English dominates. For every English title there is one in a different language.

For works in the public domain, this proportion skews even further to English—about 60 percent of titles in the public domain are English. Perhaps this reflects the needs of the faculty and students at the academic institutions currently partnering with the HathiTrust. It is quite telling that the second- and third-largest collections of works are German and French, while Spanish, the second most-spoken language in the United States, trails at a distant fourth. Only 4.48 percent of the HathiTrust online collection is in Spanish, yet 36 million people (roughly 12 percent of the population) in the United States speak Spanish as their primary language. In contrast, only about 1.3 million (or .41 percent) speak French and only about 1.1 million (about .35 percent) speak German, yet the HathiTrust collections include 7 percent and 9.2 percent of those languages respectively.2 What accounts for this lack of alignment in terms of population and language representation? Why would German, for example, despite the small percentage of people actually speaking it in the home anymore, be more prevalent in the HathiTrust collections? These questions are examined more closely in the next section.

Figure 7.1

HathiTrust data visualization showing the top ten languages represented in their collections.

MDLs’ Coverage of Traditionally Underrepresented Groups in the United States

Weiss and James (2013) focused their first study on the rate of metadata errors found in Google Books. They found a roughly 36 percent rate of error and followed this up with an investigation of the diversity of English-language content, in particular in terms of books on or originating from Hawaii and the Pacific. There were significant gaps found in the coverage, in particular a number of scannable books in the public domain did not appear in the Google Books corpus (Weiss and James 2013).

During the peer-review process for their 2012 study, however, the authors were asked why they hadn’t compared the results with the HathiTrust, Internet Archive, or other similar mass book-digitization project. In their follow-up study of Spanish-language book coverage, they took other MDLs into account and compared the results of language coverage. The results of the study were also intriguing and helped to point out further gaps in the diversity of content (Weiss and James 2013).

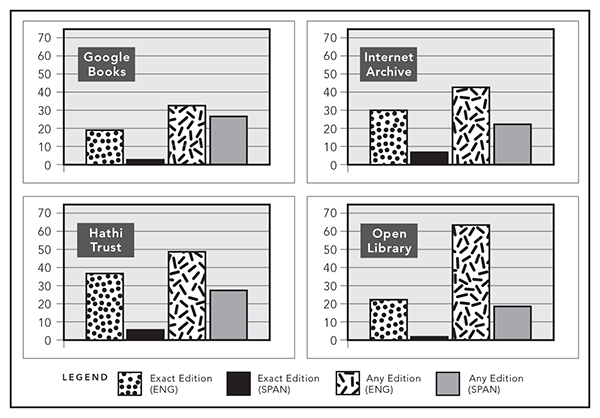

As figure 7.2 reveals, Google Books generally did not show large differences in the coverage of Spanish-language and English-language books from a random sample of eight hundred books (four hundred in Spanish, and four hundred in English) that were also in the library catalog at California State University, Northridge. In comparison, HathiTrust showed fewer overall Spanish-language titles than Google Books (nearly twice as many had no record and were therefore not in the HathiTrust’s collection). Both MDLs had similar amounts of books that were available in full view, however. This suggests that the two MDLs have determined the same titles to be in the public domain. It may be that many of the same titles were digitized by one or the other and then shared. But looking again at the number of Spanish-language books with no record in the HathiTrust, it seems that they have not been digitized because their partners do not have the books.

Figure 7.2

Levels of coverage of Spanish versus English books available as fully accessible texts (full view) in four MDLs.

(Andrew Weiss)

Considering, however, the percentage of Spanish-language books in the HathiTrust system and the lack of coverage found in the Weiss and James (2013) study, it becomes clear that attempting to create a universal library without taking the potential audience into account will only serve to accentuate the holes in a collection. The sample taken from California State University, Northridge—a federally designated Hispanic-serving institution—draws out these contrasts. If HathiTrust’s partnering institutions do not have a priority for certain subjects or languages (e.g., Spanish-language books), then the collection will reflect those gaps. This is clear. Despite Hispanics being the largest minority in the United States (with a population of 55 million) and Spanish being spoken at home by 12 percent of US households, the HathiTrust’s collection contains only a small percentage of Spanish-language books.

Again, this is a reflection of the priorities of HathiTrust’s partners. The lack of representative diversity becomes obvious when one looks at current population demographics and the amount of Spanish-language books in their collection. If libraries and universities exist to serve their students, then some shifts in focus of not only subject matter offered in curriculum but also types of materials offered (e.g., Spanish-language versions of texts) will have to occur.

University libraries have historically tended not to collect scholarly and academic titles in the Spanish language. French, German, and Latin (and ancient Greek) are much more traditionally identified as the languages used in certain disciplines in academia, especially history, philosophy, religious studies, medicine, and physics. Let us not forget that the current university system grew out of the German model and that scholarship itself was dominated by that language until very recently. Perhaps this perception of Spanish as secondary in the academic world will change over time as more Spanish speakers and Hispanics attend college in the United States. Furthermore, the percentages of French, German, and Latin books currently found in university library collections will likely fade as demographics and political fortunes shift. It appears that HathiTrust’s collections, out of no fault of its own, lag behind the real world by a generation or two. The collection likely best represents the emphasis of the various digitization partners as they would appear in the latter half of the twentieth century.

Libraries are slow to change or weed their collections, and it is possible that the underrepresentation of Spanish is a symptom of mass-digitization projects in general: they are relying on collections of materials that may be outdated to begin with. Digitization becomes a snapshot of a period of time (the mid- to late 2000s) for specific academic libraries and reflects the priorities of the institutions at that time.

Future Directions

It is clear that there is much to be read in the changes of a library collection’s makeup. It is hoped that those studying MDLs in the future would be able to access snapshots of the digital library collection at various points in time. This will help researchers and historians to track numerous changes not only in libraries but also in departments, in college and university policies, and in the overall changing demographics of college students in the United States.

The studies conducted by James and Weiss have focused on just a few of the historically underrepresented groups in the United States. There are other possible directions to take as well. A future study of mine will involve a look at Japanese-language coverage and collections in MDLs. Comparisons between Hawaiian and Pacific, Spanish-language, and Japanese-language collections (each of which is considered a traditionally underrepresented group in the United States) would be fruitful to assess the levels of diversity found in such “universal” digital libraries. Further studies might also look at how aboriginal and Native American texts might be represented in such MDLs. In the case of Japan, for example, one might consider examining the representation of Zainichi Koreans, Ainu, or Okinawan cultures, all underrepresented groups in Japan, in MDLs.

European Criticism and Approaches to Content Diversity

Jeanneney’s critique of Google in his 2007 book has been referenced often in this book and in many other places. It remains a singularly important critique of not only Google’s worldview but also its methods, which result in the possible marginalization of not only cultural institutions but whole industries and societal classes as well.

It appears that many European institutions have taken Jeanneney’s advice seriously. Gallica, Europeana, and other institutions have attempted to take very “non-Google” approaches to their MDLs. Gallica is a digital cultural portal for the French language. As such, it remains an important counterpoint to American or Anglo-centric projects. Even the HathiTrust has trouble being convincing about having acceptable levels of diversity in its collections. For example, only 7 percent of its collection actually contains French-language materials. It is unclear what the breakdown for Google Books actually is. Attempts to find this information and attempts to contact Google Books staff were not answered. Nevertheless, it is quite likely that Google Books’ level of diversity is similar to that of other non-English languages, especially as its range of partners is just as limited as, say, the HathiTrust’s. Essentially, this brings us back to the first part of our discussion: a massive digital collection development policy of digitizing everything.

To combat ethnocentric and language-centric collection development, it appears that many of the European models have attempted to gather works in the languages of their country. It may be that each language would need to develop its own MDL to ensure that the fruits of a culture are not marginalized. In the case of Google, its overreach is a matter of stepping on so many cultural, institutional, and economic boundaries. Yet the goals remain the same: to digitize everything that can be digitized. That driving force is creating ever-larger digital libraries, though it is possible that things will fall through the cracks.

Positive Trends in MDLs’ Diversity

However, not all is wrong in the world of MDLs. In fact, the aggregation of so much content online under a single search interface is itself a revolutionary undertaking. These are clearly the days of miracles and wonder. Some positive impacts on the aggregation of much content are clear. For example, a study by Chen in 2012 regarding OCLC records explains that, under the conditions of their study, any book in the Google Books project is mappable to the OCLC world catalog. Furthermore as of April 2013, OCLC announced it would be adding Google Books and HathiTrust records into its WorldCat system, creating an ever-larger system for finding books.

Second, the HathiTrust’s collections—though obviously dominated by English—nonetheless provide access to more than 420 languages. This diversity shows that the long tail of online consumerism can also be satisfied by nonprofit, educational endeavors. If more public domain works in languages with fewer speakers than English are able to make it online, there is hope that those languages might be saved or preserved. In many ways, the HathiTrust, or any MDL for that matter, can provide the digital backbone to preserve the cultures and languages of marginalized or endangered communities.

Third, many libraries are starting to link their collections to Google Books or HathiTrust through their own online catalogs. This can provide a better way to track and target the books they need to improve their own diversity in holdings. If all the public domain full-access books were cataloged and linked outward to the source materials, or if the source materials were downloaded and added to a local library’s collection, a greater number of people would be able to access this material as well. Perhaps using these open access, public domain materials will help spur a renaissance in multicultural, multilanguage, extremely diverse collection building. This will also allow other libraries to focus their limited and sometimes shrinking budgets on those books that they definitely need. These libraries can target new materials or other materials that they might never have considered before, especially if usage statistics are employed to keep track of the materials.

Conclusion

In the end collection development and collection diversity are two sides of the same coin. One needs a development policy to avoid the pitfalls of catering only to the dominant culture. The omnivorous approach of Google Books could be applied on a smaller scale to involve singular languages or cultures. However, in the case of the HathiTrust, the collections digitized represent a lag in time. What we are looking at—4.5 percent Spanish-language books—is a historical collection development policy time lag. The choice to focus on English, German, and French likely goes back 150 years to the very beginnings of higher education in the United States. Libraries had to prioritize on the basis of their users’ needs, which in the nineteenth century focused on the main languages of scholarly communication: French and German. Those needs have obviously changed in the light of not only alterations to the way the university itself communicates, the subjects offered, the ascendance of the English language in international communication, and the Hispanic immigration and the number of Spanish speakers in the United States. Finally, although there are gaps in coverage, the technology driving MDLs that allows one to better see those gaps and fill them has never been better.

Chen, Xiaotian. 2012. “Google Books Assessments: Comparing Google Books Content with WorldCat Content.” Online Information Review 36, no. 4: 507–16. doi: 10.1108/14684521211254031

Jeanneney, Jean-Noël. 2007. Google and the Myth of Universal Knowledge: A View from Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. First published in French in 2005.

LaFond, Deborah M., Mary K. Van Ullen, and Richard D. Irving. 2000. “Diversity in Collection Development: Comparing Access Strategies to Alternative Press Periodicals.” College and Research Libraries 61, no. 2: 136–44.

Weiss, Andrew, and Ryan James. 2013. “An Examination of Massive Digital Libraries’ Coverage of Spanish Language Materials: Issues of Multi-Lingual Accessibility in a Decentralized, Mass-Digitized World.” Presentation at the International Conference on Culture and Computing, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, Japan, September 16.

Notes

1. “HathiTrust Languages,” www.hathitrust.org/visualizations_languages.

2. “Language Use,” US Census Bureau, 2011, www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/language/.