044

Edward Jenner Museum, Berkeley, England

51° 41′ 24.96″ N, 2° 27′ 26.68″ W

51° 41′ 24.96″ N, 2° 27′ 26.68″ W

![]()

From Variolation to Vaccination

Prior to Edward Jenner’s invention of vaccination, smallpox was killing about 10% of the population of Europe every year. Those that survived were often left blind or seriously scarred. The only practical way of preventing smallpox infection was through variolation—deliberately infecting a person with a (hopefully mild) strain of smallpox.

Variolation had been in use since at least 1000 AD in the Far East, and later across the Middle East. It was introduced to Britain in 1721 by Lady Mary Wortley Montague, the wife of the British Ambassador to Turkey, where she had seen variolation practiced.

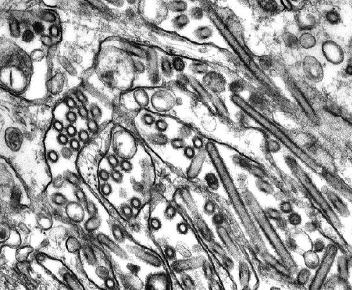

To variolate a patient, dried smallpox pustules from a mild case of smallpox were either blown up the patient’s nose or placed in a small incision in his hand. Smallpox is caused by a virus that has two forms: Variola major and Variola minor. If a patient was variolated with either one, he would become immune to the other, and by choosing a mild case of smallpox the physician hoped to be choosing Variola minor, which had a much lower death rate than Variola major. Unfortunately, at the time there was no way of distinguishing the two.

Variolation killed about 2% of patients, but protected about 80% from smallpox once they recovered. Given the high fatality rate of smallpox (about 30%), many people took the gamble of variolation.

Edward Jenner was a doctor and scientist who lived in the small town of Berkeley. He observed that milkmaids would frequently catch cowpox from the cows they were milking, and that they did not catch smallpox. Cowpox causes skin blisters in humans, and stimulates an immune system reaction that leads to protection against the similar smallpox virus.

Jenner conjectured that there was a connection between cowpox and smallpox immunity, and in 1796, he deliberately infected the eight-year-old son of his gardener with cowpox taken from a rash on a milkmaid’s hand. He scratched the boy’s arm and rubbed in the infectious material; the boy quickly developed cowpox and recovered.

Two months later Jenner variolated the boy to try to infect him with smallpox. The disease did not develop; Jenner tried again a number of times, and finally confirmed that infection with cowpox protected against smallpox. He then attempted to publish his findings, but the Royal Society rejected his paper, saying that he should “be concerned for his reputation and esteem among his colleagues.”

Jenner quickly published his results at his own expense in the book An Inquiry Into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a Disease Discovered in Some of the Western Counties of England, Particularly Gloucestershire, and Known by the Name of the Cow Pox. Within two years, vaccination was common in Europe and by 1800, was being practiced in North America.

Edward Jenner’s former home in Berkeley has been turned into a museum of his life and of modern immunology. There’s a reproduction of Jenner’s study based on an inventory taken on his death in 1823. But the real interest lies in the modern exhibit, created by the British Society for Immunology, that covers the science of immunology and vaccination.

In the garden surrounding the house is his Temple of Vaccinia, a small structure where he vaccinated the local poor free of charge.

Jenner is known for his vaccinations, but he only became a fellow of the Royal Society after publishing his observations on the life of the cuckoo. The museum helps visitors understand the importance of vaccination, but also the life of a man who was at once a local doctor and an avid scientist, and who met his future wife when a balloon experiment ended in her father’s garden.

Practical Information

You can find visiting, historical, and immunology information on the museum’s website at http://www.jennermuseum.com/.